Value Chain Analysis: Porter's Model & Competitive Advantage

advertisement

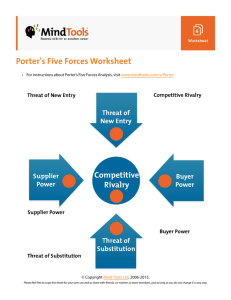

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280246631 value chain Chapter · January 2014 CITATIONS READS 0 37,266 1 author: John McGee The University of Warwick 137 PUBLICATIONS 1,657 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Wiley Encyclopedia of Management - Vol 12 Strategic Management View project individual research View project All content following this page was uploaded by John McGee on 22 July 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. chosen strategy of the firm. These categories can be described as follows: value chain John McGee The activities that a firm performs become part of the value added produced from a raw material to its ultimate consumption. Figure 1 shows how the supply chain forms the basic spine of the Five Forces analysis. It contains all the activities required to bring the final product or service to the final customer. Along the way many different firms or businesses have their own activities along the supply chain. Thus, each firm has its own value chain, a subset of the supply chain. Figure 1 is Porter’s classic picture of the value chain. It has two parts. The lower part contains those activities (labeled primary activities) that are organized in sequence just like a production line. Thus, inbound logistics is the first step, leading to manufacturing operations, then outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and eventually service. This is a caricature of each firm’s value chain and will contain different headings according to the nature of the operations. Value is the amount that buyers are willing to pay for the product or service that a firm provides. Profits alter when the value created by the firm exceeds the cost of providing it. This is the goal of strategy, and therefore value creation becomes a critical ingredient in competitive analysis. Every value activity employs costs such as raw materials, and other purchased goods and services for “purchased inputs,” human resources (direct and indirect labor), and technology to transform raw materials into finished goods. Each value activity also creates information that is needed to establish what is going on in the business. Similarly, value is created by reducing stocks, accounts receivable, and so on, while value is lost via raw material purchases and other liabilities. Most organizations, thus engage in many activities in the process of creating value. These activities can generally be classified into either primary or support activities. These are illustrated in Figure 1, which details the view of Michael Porter, who states that there are five generic categories of primary activities involved in competing in any industry. Each of these is divisible into a number of specific activities that vary according to the industry and • Inbound logistics. Activities associated with receiving, storing, and disseminating rights to the product, such as material handling, warehousing, stock management, and so on. • Operations. All of the activities required to transform inputs into outputs and the critical functions which add value, such as machining, packaging, assembly, service, testing, and so on. • Outbound logistics. All of the activities required to collect, store, and physically distribute the output. This activity can prove to be extremely important both in generating value and in improving differentiation, as in many industries control over distribution strategies is proving to be a major source of competitive advantage – especially as it is realized that up to 50% of the value created in many industry chains occurs close to the ultimate buyer. • Marketing and sales. Activities associated with informing potential buyers about the firm’s products and services, and inducing them to do so by personal selling, advertising and promotion, and so on. • Service. The means of enhancing the physical product features through after-sales service, installation, repair, and so on. The second part of the value chain is the upper section which contains all the overhead service elements (labeled support activities) required by the firm. In Porter’s picture he named four elements, firm infrastructure, human resource management, technology development, and procurement: 1. Procurement. This concerns the acquisition of inputs or resources. Although, technically this is the responsibility of the purchasing department, almost everyone in the firm is responsible for purchasing something. While the cost of procurement itself is relatively low, the impact can be very high. 2. Human resource management. This consists of all activities involved in recruiting, hiring Wiley Encyclopedia of Management, edited by Professor Sir Cary L Cooper. Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2 value chain Firm infrastructure Human resource management Support activities Technology development Procurement Service Inbound logistics Operations Outbound logistics Marketing & sales Primary activities Figure 1 The generic value chain. Source: Porter (1985). 3. 4. and training, developing, rewarding, and sanctioning the people in the organization. Technology development. This is concerned with the equipment, hardware, software, technical skills, and so on, used by the firm in transforming inputs to outputs. Some such skills can be classified as scientific, while others – such as food preparation in a restaurant – are “artistic.” Such skills are not always recognized. They may also support limited activities of the business, such as accounting, order procurement, and so on, and in this sense may be likened to the value added component of the experience effect. Firm infrastructure. This consists of the many activities, including general management, planning, finance, legal, external affairs, and so on, which support the operational aspect of the value chain. This may be self-contained in the case of an undiversified firm or divided between the parent and the firm’s constituent business units. Within each category of primary and support activities, Porter identifies three types of activity, which play different roles in achieving competitive advantage: • Direct. These are activities directly involved in creating value for buyers, such as assembly, sales, and advertising. • • Indirect. These are activities that facilitate the performance of the direct activities on a continuing basis, such as maintenance, scheduling, and administration. Quality assurance. These are activities that insure the quality of other activities, such as monitoring, inspecting, testing, and checking. The value chain is another generic framework that permits a range of applications and analyses. It permits the analyst to divide the firm’s activities into broad categories (as above) and increasingly into more specific categories. Thus, operations might be refined into subcomponents and assembly: marketing and sales into market research, product development, sales force, and so on. The usefulness of this is to be able to identify those activities that are the source of the competitive advantage and to be able to locate them within the value chain. For example, if Intel’s competitive advantage is product performance and this is derived (at least in large part) from R&D activities, then this can be isolated within the value chain and measured, compared to competitors, and provided with support. Competitive advantage is often quite subtle in its manifestation and in its sources. Cost advantage might arise from the way in which every single activity in the value chain is linked to the others and managed for efficiency. The story of value chain the low-cost airlines such as EasyJet, Ryanair, and Southwest Airlines is about system management of the costs as well as focus on driving down each cost component. Differentiation may be delivered as a service quality perception driven by the way in which each element of service delivery is managed systematically along with all other elements in order to differentiate the product. The value chain can be a powerful tool in diagnosing and explaining how the management of competitive advantage takes place within the firm. The interrelationships between the elements of the value chain provide an important explanation of the nature of competitive advantage in large, complex organizations. Such organizations typically are rich in tacit knowledge. This is the kind of knowledge that you call upon to ride a bicycle. We all know how to do this – but it is impossible to explain it. Similarly, large corporations are used to making links between complex and far-flung activities, and between related and unrelated technologies. This “glue,” binds these companies together and makes it impossible for others to imitate quickly. The “hidden” part of the value chain is these linkages that contain the tacit knowledge. The way this “glue,” works determines the level of vertical integration, that is, those elements of the supply chain that can be brought within the value chain and within the firm and those that should remain outside the firm. The guiding principle is that when the costs of internal transactions (making the glue work properly) exceed the costs of buying outside, then the firm should source outside its boundaries. THE VALUE CHAIN AND COST ANALYSIS The value chain provides a good basis on which to conduct a cost analysis. Its principal advantage is that the elements of the value chain are already organized around those issues that are important in driving competitive advantage and profitability. Porter (1985) was, therefore, able in his book to make very strong links with the array of literature and practice on cost cutting that was already available. A criticism of the cost analysis literature was the difficulty of defining 3 the correct units of analysis, an issue which the value chain solved brilliantly. Therefore a normal cost analysis procedure can take place with the following stages.1 1. Define the value chain in terms of those elements that relate to the sources of competitive advantage. Key considerations are – the separateness and independence of one activity from another; – the importance of an activity in relation to competitive advantage and to the margin; – the dissimilarity of activities in terms of requiring different cost drivers; – the extent to which there are differences in the way competitors perform activities (i.e., where there are differences there are potential advantages to be gained). 2. Establish the relative importance of different activities in the total cost of the product. This means assigning costs to each activity based on management accounts or other customized analysis procedures. The distinctions made earlier about fixed and variable costs, sunk costs, and cost allocations are really significant issues at this stage. Errors in cost analysis can lead to significant misunderstanding of what contributes to profits and how valuable is a competitive advantage. 3. Compare costs by activity and benchmark against competitors. The comparison is not in terms of how big are the costs but how different are they from efficiency benchmarks and from competitor standards. 4. Identify cost drivers. These are the forces that move costs up or down. Planned scale of activities is a driver of overall plant cost and so also is degree of capacity utilization. A driver of sales force costs might be product range – if the range is too small costs will be high. Another driver will be geographical concentration of customers and another might be sales communication methods (face to face or remote teleconferencing). For labor intensive activities critical drivers might be wage rates, speed of production line, and defect rates. It is through the 4 value chain understanding of cost drivers that signifies how well you understand the nature of your business. One needs to look behind the obvious to identify the fundamentals. 5. Identify linkages between activities. Interrelationships may be very many in number – the critical cost drivers may seemingly relate to another activity entirely. A comparison can be made between Xerox and Canon in the photocopying industry. Xerox found that its service costs were driven by design complexity and manufacturing inefficiencies. Grant observes that: … the optimisation of activities through the value chain has become a major source of cost reduction, and speed enhancement has become a key challenge for computer integrated manufacturing. (Grant, 2002, p. 271) 6. Identify opportunities for reducing costs. By identifying areas of obvious inefficiency (i.e., deviations from designed machine performance standards) and of deficiencies against competitive benchmarks, opportunities for cost reduction become evident. Very often the option is posed of contracting outside the firm for components or services. Some firms have subcontracted entire IT departments. Currently, European firms are outsourcing their call centers to India. The automobile companies are going through an extensive process of outsourcing. The Ford Fiesta plants in Cologne outsource fully made-up doors (as a subsystem) to plants adjacent to the Ford plant. IDENTIFYING THE VALUE CHAIN The value chain concept thus helps to identify cost behavior in detail. From this analysis, different strategic courses of action should be identifiable to develop differentiation and less price sensitive strategies. Competitive advantage is then achieved by performing strategic activities better or cheaper than competitors. To diagnose competitive advantage, it is necessary to define the firm’s value chain for operating in a particular industry and compare this with those of key competitors. A comparison of the value chains of different competitors often identifies ways of achieving strategic advantage by reconfiguring the value chain of the individual firm. In assigning costs and assets it is important that the analysis be done strategically rather than seeking accounting precision. This should be accomplished using the following principles: • • • • operating costs should be assigned to activities where incurred; assets should be assigned to activities where employed, controlled, or influencing usage; accounting systems should be adjusted to fit value analysis; asset valuation may be difficult but should recognize industry norms – particular care should be taken in evaluating property assets. The reconfiguration of the value chain has often been used by successful competitors in achieving competitive advantage. When seeking to reconfigure the value chain in an industry, the following questions need to be asked: • • • how can an activity be done differently or even eliminated? how can linked value activities be reordered or regrouped? how could coalitions with other firms reduce or eliminate costs? Successful reconfiguration strategies usually occur with one or more of the following moves: a new production process, automation differences, direct versus indirect sales strategy, the opening of new distribution channels, new raw materials used, differences in forward and/or backward integration, a relative location shift, and new advertising media. A good example of this is the emergence of German volume discounters (Lidl and Aldi) on the UK food retailing scene. According to The Economist (2008) these “hard” discounters “stock a fraction of the goods that a normal supermarket offers, resulting in fewer suppliers, a high volume of purchases and sales, and massive economies of scale.” The German discount model is based on a different combination of competitive positioning and value chain configuration resulting in a new and possibly better business model according to some observers.2 value chain ENDNOTES 1 This section draws on Grant (2002, Chapter 7). 2 For instance, Philippe Suchet of Exane BNP Paribas in Paris quoted in The Economist (2008). Bibliography Grant, R.M. (2002) Contemporary Strategy Analysis: Concepts, Techniques and Applications, 4th edn, Blackwell Business, Oxford. View publication stats 5 McGee, J., Wilson, D. and Thomas, H. (2010) Strategy: Analysis and Practice, 2nd edn, McGraw-Hill, Maidenhead. Porter, M.E. (1985) Competitive Advantage; Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, The Free Press, New York. The Economist (2008) The Germans are coming, 16 August.