5

Alternations: Stems

and Allomorphy

Mary Paster

1

Introduction

This chapter discusses stem allomorphy and its theoretical analysis. Four

different general theoretical approaches to the analysis of stem allomorphy

are presented, and their positive and negative attributes are evaluated

relative to what is currently known about properties of stem allomorphy

cross-linguistically. It is argued that no single model is ideal to account

for all types of stem allomorphy; therefore, it is proposed that multiple

frameworks may be needed. The distribution of labor among those models

is discussed as an issue for future research, pending refinement of our

understanding of the typology of stem allomorphy based on further crosslinguistic research and in-depth empirical studies of morphologically complex languages.

“Allomorphy” is defined here as any case of a single set of semantic/

morphosyntactic features having two or more different context-dependent

phonological realizations. This includes cases where a straightforward

phonological rule/constraint may be invoked as well as more complex

examples involving suppletive allomorphy, where multiple underlying

forms are involved whose distribution may be morphologically, lexically,

and/or phonologically governed. A “stem” is defined as a form that can be

inflected (meaning that a stem may consist only of a root, or it may be a root

plus one or more derivational and/or inflectional affixes). Although most

allomorphy probably occurs in affixes rather than stems, the examples in

this chapter will be of allomorphy specifically in stems wherever possible,

given the focus of the chapter. (For discussion of affix allomorphy, as it

relates to paradigms, see Chapter 9 of this volume.)

The chapter will be structured as follows. In Section 2, I present an

overview of the basic types of allomorphy, giving examples of each.

In Section 3, I describe four different theoretical models, explaining how

each would analyze a sample case of stem allomorphy. In Section 4,

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

94

MARY PASTER

I discuss some outstanding research questions relating to stem allomorphy. Section 5 concludes the chapter.

2

Types of Allomorphy

Allomorphy was defined above as “any case of a single set of semantic/

morphosyntactic features having two or more different context-dependent

phonological realizations,” but it should be noted that there exist other

definitions of the term. Before describing the types of allomorphy, I will

provide some background regarding the concept and other understandings

of it. See also Paster (2014, to appear) for further discussion.

The definition of allomorphy being used here subsumes phenomena that

many researchers would view as having two fundamentally different loci/

sources—namely, some would be considered phonological in nature and

others morphological. Section 5 will provide further discussion of the

architecture of the grammar and how different theoretical approaches to

allomorphy relate to different ideas of the distinction (if any) between

phonology and morphology. The present definition of allomorphy is

focused on the surface form of the stem. Instances where the phonological

form of the stem varies contextually are all considered to be examples of

allomorphy under this definition, regardless of which component of the

grammar is responsible for the variation. A distinction can then be made

between what I refer to as “suppletive allomorphy” (defined below, and

used interchangeably here with the term “suppletion”), which involves

multiple underlying forms and is therefore a result of morphological functions of the grammar, versus non-suppletive allomorphy, which involves a

single underlying form where variation is due to the action of regular rules/

constraints in the phonological component of the grammar.

Some researchers, however, would refer to non-suppletive allomorphy as

“morphophonology,” reserving the term “allomorphy” specifically for suppletive allomorphy. Further, at least one definition of “allomorphy” (Stockwell

and Minkova 2001: 73) is not only limited to what I call suppletive allomorphy,

but it also requires allomorphs to have a “historically valid” relationship—in

other words, that they are etymologically related. In Stockwell and Minkova’s

typology, cases of what I call suppletive allomorphy but where the underlying

forms are not phonetically similar would not be described as allomorphy; the

phenomenon would be labeled “suppletion” (but not “suppletive allomorphy”)

in the case of stems, or “rival affixes” in the case of affixes. Under the definitions of “allomorphy” and “suppletive allomorphy” (or “suppletion”) that I am

using in this chapter, there is no distinction between the phenomena referred

to by Stockwell and Minkova as “rival affixes” versus “suppletive allomorphs.”

Having defined some important terms and provided some clarification

regarding how my use of the relevant terminology relates to that of other

researchers, I turn now to a discussion of the types of allomorphy.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

Alternations: Stems and Allomorphy

95

To begin, it is useful to distinguish two major types of allomorphy, as

alluded to above. The first is non-suppletive phonologically derived allomorphy. This is a situation where a regular phonological rule of a language

applies in a particular phonological context, yielding alternations. This type

of allomorphy commonly applies to stems, even if it applies preferentially

to affixes and not stems in some languages. An example of regular phonologically conditioned stem allomorphy is found in Polish, which exhibits

word-final obstruent devoicing. When a stem underlyingly ends in a voiced

obstruent, if there is no suffix after the stem, the devoicing rule produces a

stem allomorph with a final voiceless obstruent, as can be seen by comparing the genitive singular versus nominative singular forms of the nouns in

(1) (note that examples are given as phonetic transcriptions rather than in

the Polish orthography, which does not reflect devoicing).

(1) Gen sg

klub-u

ob jad-u

targ-u

gaz-u

stav-u

gruz-u

Nom sg

klup

ob jat

tark

gas

staf

grus

Gloss

‘club’

‘dinner’

‘market’

‘gas’

‘pond’

‘rubble’

A straightforward analysis would have a single underlying form of the

stem, reflected in the genitive singular form, and a regular phonological

rule applying in the nominative singular, where the lack of a suffix puts the

stem-final segment into the word-final environment that triggers devoicing. Thus, the allomorphy is derived purely in the phonology. (Note that

this must be analyzed as word-final devoicing rather than pre-vocalic

voicing, since stem-final underlyingly voiceless obstruents do not alternate;

cf. pobɨt~pobɨt-u ‘stay.’)

The second major type of allomorphy is suppletive allomorphy. This is a

type of allomorphy where there are two or more underlying forms that

express the same set of semantic/morphosyntactic features. The grammar

must somehow select among the different underlying forms, whose surface

realizations are in complementary distribution. The basis for selection may

be morphosyntactic, lexical, or phonological—or a combination of these.

We deal with each of these types of suppletive allomorphy below.

In morphosyntactically conditioned suppletive allomorphy, the selection

of an allomorph is conditioned by the morphological or syntactic category

of the word. In the case of stem allomorphy, a specific form of a stem might

be used in a particular morphological context such as past tense versus

other tenses, or when the word belongs to a particular syntactic category

such as when it is used to form a noun vs. a verb. An example is found in

Hopi, as shown in (2), where certain nouns have a stem form used in the

plural that differs in unpredictable ways from the stem form used in the

singular and dual (Hill and Black 1998: 865; Haugen and Siddiqi 2013).

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

96

MARY PASTER

(2) Singular

wùuti

tiyo

pöösa

Dual

wùuti-t

tiyo-t

pöösa-t

Plural

momoya-m

tooti-m

pövöya-m

Gloss

‘woman’

‘boy, young man’

‘house mouse’

This case of allomorphy is treated as suppletive since there is no uniform

phonological change to the stem in the plural relative to the singular/dual

form. It is morphologically conditioned since it is the plural category that

triggers the use of the special stem form. Crucially, a given case of stem

allomorphy is only analyzed as morphosyntactically conditioned suppletive

allomorphy if it is the morphosyntactic category per se that conditions the

use of the allomorph, rather than a phonological property of that morphosyntactic category. For instance, the use of the allomorph [twɛlf] with a

voiceless stem-final consonant in the English word twelfth is conditioned by

the ordinal suffix, but this should probably not be considered morphosyntactically conditioned suppletive allomorphy because (1) it is arguably the

voicelessness of the suffix (and not the fact that it is an ordinal form) that

conditions the use of a stem allomorph with a voiceless final consonant;

and (2) the allomorphy is not suppletive since it can be analyzed via a

phonological devoicing rule.

Lexically conditioned suppletive allomorphy defines a situation where

suppletion is idiosyncratic to particular lexical items. Lexically conditioned

suppletion is probably more relevant in the domain of affix allomorphy than

stem allomorphy, and in fact lexically conditioned suppletion in the domain

of stem allomorphy will necessarily involve some additional type of conditioning (since some other property in addition to the lexical item needs

to vary in order for allomorphy to manifest itself). Lexically conditioned

suppletive allomorphy often occurs in tandem with morphosyntactic

conditioning—for example, different classes of verbs in a language may have

different conjugation patterns (which would usually be categorized as

allomorphy in the inflectional endings, rather than in the stem). A parallel

example involving stem allomorphy would be one where, for example, a

certain class of verbs has a special stem form that is used in certain tenses.

An example is the so-called “strong” verbs in Germanic languages (verbs like

eat, sing, and break), whose past tense forms have a special stem allomorph

that is historically derived from phonological ablaut but is arguably suppletive (at least in modern English). The remainder of this chapter will not

consider the lexically conditioned type of suppletion in as much detail as

the other types, given its limited relevance to stem allomorphy specifically.

A final type of suppletive allomorphy is phonologically conditioned suppletive allomorphy (PCSA). This is a phenomenon where the selection of

suppletive allomorphs is determined by a phonological criterion. This situation is crucially different from the type of regular phonological allomorphy described earlier where a single underlying form corresponds to

multiple surface forms due to the operation of a phonological rule, since

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

Alternations: Stems and Allomorphy

97

PCSA by definition involves multiple underlying forms. Interestingly,

although many cases of PCSA seem to mirror the effect of phonological

rules in terms of the surface results of a particular distribution of allomorphs, this is not always the case; sometimes the distribution of allomorphs appears to be phonologically arbitrary (though still phonologically

determined). In the realm of stem allomorphy, cases of PCSA as defined

here seem to be rare. In fact, as discussed below in Section 3.1, in lexical

subcategorization-based approaches to allomorphy, strictly speaking, PCSA

in stems is predicted not to exist. However, some cases are known. An

example that could be seen as phonologically conditioned stem allomorphy

is found in Italian (Hall 1948), where some stems have allomorphs ending in

/isk/ that occur only in morphological contexts where the word stress falls

on the stem-final syllable—namely, in the present and subjunctive 1sg, 2sg,

3sg, and 3pl and in the 2sg imperative (Hall 1948: 25, 27). One such stem is

fin- “finish”; some examples are shown in (3) (Hall 1948: 214) with the forms

in [isk] (and its surface phonological variant [iʃʃ ]) shown in bold.

(3)

Present

finísk-o

finíʃʃ-i

finíʃʃ-e

‘I finish’

‘you (sg) finish’

‘s/he finishes’

fin-iámo

fin-íte

finísk-ono

‘we finish’

‘you (pl) finish’

‘they finish’1

Subjunctive

finísk-a

finísk-a

finísk-a

‘that I finish’

‘that you (sg) finish’

‘that s/he finish’

fin-iámo

fin-iáte

finísk-ano

‘that we finish’

‘that you (pl) finish’

‘that they finish’

‘(you (sg)) finish!’

fin-iámo

fin-íte

‘let’s finish’

‘(you (pl)) finish!’

Imperative

finíʃʃ-i

Other stems of this type include ağ- ‘act,’ argu- ‘argue,’ dilu- ‘add water,’

mεnt- ‘lie,’ diminu- ‘diminish,’ and ammon- ‘admonish’ (Hall 1948: 43–5,

52, 61). There appears not to be any semantic or phonological generalization regarding which stems pattern with this class of verbs in Italian, so the

allomorphy must be lexically conditioned (arbitrarily, by the specific verb

stem) in addition to being phonologically conditioned.2

1

Thanks to Anna Thornton for correcting the transcription of this form, which was incorrectly reported in Paster 2006.

2

I have described the Italian case in terms of the phonological generalization, but the standard analysis appears to be in

terms of arbitrary stem patterns. A number of verbs other than the isc verbs have the same pattern in the present tense

(having a stem form that appears with 1sg, 2sg, 3sg, and 3pl subjects and a different form occurring with 1pl and 2pl);

Maiden 2004 terms this the “N pattern.” Interestingly, there are multiple other types of N-pattern stems that do not

involve isc, including some where a vowel differs between the two versions of the stem but not in a way that is

described by a regular synchronic phonological rule, and the verb andare, whose two stem variants are etymologically

unrelated. The fact that these three very different types of N-pattern stems can all be described in the same

phonological terms may be used in support of an account in terms of phonological optimization, but a more standard

view seems to be that the N pattern is an abstract morphological pattern that diachronically has attracted a number of

stems into its class (see, e.g., Thornton 2007; Da Tos 2013).

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

98

MARY PASTER

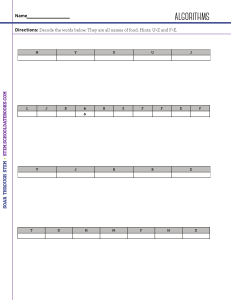

Phonological

Suppletive (multiple underlying forms)

(one underlying form)

Phonological Morphosyntactic

(PCSA)

Lexical

Figure 5.1. Types of allomorphy

To summarize the typology of allomorphy that I have presented above,

we have discussed two main types of allomorphy (regular phonological

allomorphy and suppletive allomorphy), and, within what I have called

suppletive allomorphy, three subtypes based on the type of conditioning

involved. We can schematize this conception of allomorphy as in Figure 5.1.

It should be pointed out that many cases of suppletive allomorphy are

conditioned simultaneously by more than one of the factors represented in

Figure 5.1. It has already been observed that for stems specifically, lexical

conditioning is accompanied by another type of conditioning, such as

morphological conditioning, as in the example of the Germanic strong

verbs. Another example of multiple types of conditioning is the Hopi case,

where it was noted that only certain nouns exhibit the pattern in (2). Other

nouns have uniform stem forms for singular, dual, and plural. Thus, in

addition to being morphologically conditioned (by the plural category), this

case of stem allomorphy is also lexically conditioned by the noun being

used. The morphologically conditioned stem suppletion only applies if the

noun does not belong to the regular class, whose membership, if arbitrary,

would have to be called lexical. Any adequate theory of suppletive allomorphy will have to be able to accommodate the common situation where more

than one type of conditioning factor is involved.

Having seen a few examples of stem allomorphy and discussed how the

different types are categorized, we turn now to the discussion of how stem

allomorphy can be analyzed theoretically.

3

Analyzing Stem Allomorphy

In this section, I present four different theoretical approaches to the analysis of stem allomorphy. In each case I give an overview of how stem

allomorphy is handled using each theory, and then I discuss the advantages

and drawbacks of each theory with respect to how well the known cases of

stem allomorphy are handled. Some discussion, particularly in Section 3.1

and Section 3.2, draws considerably from Paster (2015), to which I refer the

reader for more detail about the treatment of the PCSA type of suppletive

allomorphy in particular.

The four approaches to be discussed in this section are lexical

subcategorization (§3.1), constraint-based approaches (§3.2), allomorphy

rules (§3.3), and indexed stems (§3.4). We begin with lexical subcategorization.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

Alternations: Stems and Allomorphy

99

3.1 Lexical Subcategorization

In a subcategorization model (Lieber 1980; Kiparsky 1982; Selkirk 1982;

Inkelas 1990; Orgun 1996; Yu 2003, 2007; Paster 2006), affixation satisfies

missing elements specified in the lexical entries of morphemes. In this type

of model, suppletive allomorphy is a phenomenon that results when two or

more different morphemes with identical morphosyntactic and semantic

specifications3 have different phonological forms and different subcategorizational requirements. These requirements are schematized via subcategorization frames, which indicate the selectional requirements imposed

by morphemes.

To illustrate how this model works, we return to the Hopi example

presented in Section 2, repeated in (4).

(4) Singular

wùuti

tiyo

pöösa

Dual

wùuti-t

tiyo-t

pöösa-t

Plural

momoya-m

tooti-m

pövöya-m

Gloss

‘woman’

‘boy, young man’

‘house mouse’

Representations of subcategorization frames for the two stem forms of

‘woman’ are given in (5a), and a subcategorization frame for the plural

suffix is given in (5b).

(5)

a.

b.

‘woman’ (plural stem)

[[momoya-]stem, plural ] word,

[[ ]stem -m ] word, plural

plural

‘woman’ (elsewhere stem)

[wùuti-]stem

A higher-level node representing the plural word momoya-m ‘women’ is

shown in (6), with the plural stem and plural suffix as its daughters.

(6)

[[momoya-]stem, plural -m] word, plural

[[momoya-]stem, plural ] word, plural

[[

]stem -m] word, plural

This is a complete word, since the missing elements in the subcategorization frames of both daughters have filled each other in, yielding a representation with no gaps.

Some theoretical questions arise in the representation of the two stem

variants in this example. First, why is it not specified that the plural suffix

3

By some definitions of the term “morpheme,” multiple underlying phonological forms that have identical

morphosyntactic and semantic features would all be considered to be stored as one “morpheme.” That definition is not

useful in the present context, since suppletive allomorphy relies on there being multiple stored underlying forms (soundmeaning pairs), and we need a term to identify each of those stored forms. Some researchers might use the term

“morph” for this purpose, but since the term “morph” does not capture the fact that we are referring to underlying forms

rather than surface alternants, I use the term “morpheme” instead. In this chapter I will not address the question of

whether there is a linguistically significant higher-level unit that subsumes all of the stored forms that have the same

morphosyntactic and semantic properties but possibly different phonological forms and/or subcategorizational

requirements (i.e., groups of what I am calling “morphemes” that have identical morphosyntactic/semantic features).

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

100

MARY PASTER

subcategorizes for a plural stem, and given this, how does the plural suffix

select for the plural stem in words like “woman”? The reason that the

plurality of the stem is not specified in the subcategorization frame of the

plural suffix is that, as mentioned earlier, some stems do not have a special

allomorph in the plural. Some examples of these regular nouns are given in

(7) (Hill and Black 1998: 870; Haugen and Siddiqi 2013).

(7) Singular

sino

kawayo

Tasavu

Dual

sino-t

kawayo-t

Tasavu-t

Plural

sino-m

kawayo-m

Tasavu-m

Gloss

‘person’

‘horse’

‘Navajo’

Specifying that the plural suffix subcategorizes for a plural stem would

have the undesirable consequence of requiring that nouns like those in

(7) have two homophonous, listed stems—one specified as plural and one

not. This is why the subcategorizational requirement of the plural suffix is

stated only as a “stem” rather than a plural stem. The plural suffix’s

selection of the plural stem, in nouns where a special plural stem exists,

follows from Pānini’s principle (i.e., the selection of the elsewhere stem is

_

blocked by the availability of a more highly specified stem that is still

compatible with the affix).

Now that we have seen how this model deals with morphosyntactially

conditioned suppletive allomorphy, I will briefly discuss how it handles

other types of allomorphy. Regarding lexically conditioned allomorphy, as

we have already discussed, some additional type of conditioning will always

be present when the allomorphy involves stems. Consider the lexically

conditioned aspect of the Hopi example discussed above. What differentiates

the suppletive stems from the regular stems in this case, in a lexical subcategorization approach, is simply the fact that the suppletive stems have two

separate stored forms, while the regular stems have only one. Examples like

the Germanic strong verbs would be treated similarly, except that the past

tense form of a strong verb stem would not subcategorize for a suffix; it

would merely be limited to occurring in the context of a past tense word.

A representation of the past tense of a strong verb might be as shown in (8).

(8)

[[sang]stem, past]word, past

[[sang]stem, past

] word, past

[[

]stem Ø] word, past

A possible criticism of this approach to Germanic strong stems is that it

fails to capture the phonological systematicity of the stem alternations (i.e.,

that the past tense stem is identical to the elsewhere stem except for the

last vowel, which exhibits ablaut). This relates to the more general criticism

of the subcategorization approach (what Embick 2010 refers to as the

“putative loss of generalization argument”) that it treats apparent

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

Alternations: Stems and Allomorphy

101

regularities in allomorph distribution as arbitrary or coincidental. The

position that will be adopted here, regarding the Germanic example, is

that the apparent ablaut is the reflex of a phonological rule that is inactive

in the phonology of modern English. Thus, from the point of view of the

synchronic grammar, the apparent systematicity of the vowel changes in

strong stems is indeed coincidental; the stem variants are lexically listed,

and as far as the grammar is concerned, the vowel alternations could just as

easily be completely unsystematic and random-seeming if the history of the

language had somehow unfolded that way. Support for this view comes

from the lack of a regular ablaut rule in the phonology of modern English

and the impossibility of writing a plausible rule (or constraint ranking) to

account in phonological terms for the alternations.

I have discussed the treatment of PCSA in the subcategorization approach

at length elsewhere (see Paster 2005, 2006, 2009, 2014, 2015, to appear, and

references therein). Briefly, the approach to PCSA is identical to the

approach to morphosyntactically conditioned suppletion, except that the

element that is subcategorized for in PCSA is phonological, rather than

morphosyntactic. This possibility was made explicit by, for example, Orgun

1996 and Yu 2003. This allows the subcategorization frame to account not

only for PCSA, but also for affix placement (prefix, infix, suffix). See Paster

(2009) for an overview.

Regarding the Italian example discussed in Section 2, because the lexical

subcategorization approach requires words to be built from the inside out,

the model as I have defined it here does not allow phonological properties of

affixes to condition PCSA in stems. This does have the advantage of explaining the apparent extreme rarity of examples of this type (see, e.g., Paster

2006), but it also requires a reanalysis of those examples so that we can

understand them as being consistent with the “inside-out” generalization.

One important fact about the Italian case is that, segmentally, the shorter

stem allomorph is a subset of the longer allomorph. This allows us to

analyze -isc as a separate affix. Some previous analyses of Italian stem

allomorphy (e.g., DiFabio 1990; Schwarze 1999) do treat -isc as an affix or

“stem extension.” Analyzing -isc as an affix is helpful in reconciling the

example with the lexical subcategorization model, but it is still problematic

since this would still appear to be an example of PCSA with an “inner”

suffix being conditioned by an “outer” suffix, which is also not allowed by

the model. A further move that we need to make in order to maintain the

“inside-out” generalization is to analyze -isc- an infix rather than a suffix.

This allows us to assume that the word is built as follows: first, the subject

agreement suffix is added to the root, and then the -isc- infix (which I assume

to have inherent stress) will be inserted between the root and the suffix

whenever the suffix is not inherently stressed. The infixing analysis may

provoke some skepticism, but, in fact, this has been proposed independently; for example, DiFabio (1990) and others analyze -isc- (or -sc-) as an infix.

While the infixing analysis may seem like a trick to uphold the “inside-out”

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

102

MARY PASTER

generalization, one must concede that the lack of cases of phonologically

conditioned stem allomorphy is striking given the number of cases involving affix allomorphy. Furthermore, it is not the case that any possible

putative case of stem allomorphy could be explained away. The infixation

account is possible for Italian because isc is present in all of the

extended stems.

Regarding the treatment of cases of non-suppletive allomorphy such as

the Polish example described in Section 2, the lexical subcategorization

model does not necessarily dictate a particular approach. It is compatible

with both constraint-based and rule-based theories of phonology. One thing

to be mentioned in this regard is that in the version of lexical subcategorization that I have articulated here and elsewhere, it is assumed that phonology and morphology are separate components of the grammar, and that

all regular phonology occurs after morphology, modulo interleaving as in

Lexical Phonology (Kiparsky 1982). Given this, subcategorization frames,

being part of the lexicon/morphology, are not especially relevant to regular

phonological alternations in stems. The morphology, via subcategorization,

merely supplies the underlying forms to which the regular phonology later

applies.

An advantage to this approach is that it correctly predicts opaque interactions between suppletive and non-suppletive allomorphy in a single language. An example of this, as I have discussed in Paster (2009), comes from

Turkish (Lewis 1967) (from the domain of affixes; I am not aware of cases of

stem allomorphy that behave this way). As seen in (9), the third-person

possessive suffix has suppletive allomorphs /-i/ and /-si/. The /-i/ form occurs

when the stem ends in a consonant, while the /-si/ form occurs when the

stem ends in a vowel (examples are from Aranovich et al. 2005 and from

Gizem Karaali, personal communication; note that vowel alternations are

due to regular Turkish vowel harmony).

(9)

bedel-i

ikiz-i

alet-i

‘its price’

‘its twin’

‘its tool’

deri-si

elma-sɪ

arɪ-sɪ

‘its skin’

‘its apple’

‘its bee’

At first, this looks like a straightforward case of PCSA. We could analyze

the /-i/ form as subcategorizing for a consonant at the end of the stem, and/

or the /-si/ allomorph subcategorizing for a vowel at the end of the stem.

However, Aranovich et al. (2005) point out that the selection of the suffix

allomorph is opaque in some words due to the operation of a regular Velar

Deletion rule (Sezer 1981) that deletes intervocalic /k/. Some examples are

given in (10).

(10) açlɪ-ɪ

bebe-i

gerdanlɪ-ɪ

ekme-i

‘its

‘its

‘its

‘its

hunger’ (cf. açlɪk ‘hunger’)

baby’ (cf. bebek ‘baby’)

necklace’ (cf. gerdanlɪk ‘necklace’)

bread’ (cf. ekmek ‘bread’)

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

Alternations: Stems and Allomorphy

103

In these examples, it appears that the /-i/ form has been incorrectly

selected after a vowel, but the citation forms show that each of these stems

is underlyingly consonant-final. The lexical subcategorization approach

allows for a simple explanation of the pattern: the morphology selects the

/-i/ allomorph of the possessive suffix in these forms due to the presence of

stem-final /k/ in the underlying form. The affixed forms are then passed on to

the phonology. Due to the presence of the /-i/ suffix, the /k/ is now in intervocalic position and is therefore deleted. Such cases of opacity are more

difficult to deal with in constraint-based approaches, to which we now turn.

3.2 Constraint-based Approaches

A constraint-based approach to allomorphy uses conflicting constraints to

account for allomorph distribution. In the case of suppletive allomorphy, a

classic constraint-based approach to PCSA in Optimality Theory (OT) is the

‘P >> M’ ranking schema (McCarthy and Prince 1993a, 1993b), later

updated by Wolf (2008, 2013) (see also Chapter 20 of this volume for more

on OT approaches). The basic idea is that a phonological markedness

constraint (P), such as a constraint on syllable structure, outranks a morphological constraint (M), such as one requiring that a certain morphological category should always be marked by one particular variant of an

affix. Where relevant, the phonological constraint can force the morphology to deviate from the preferred surface realization of the morpheme in

question, instead choosing an allomorph that allows the word to satisfy the

phonological constraint while still expressing the function/meaning of the

morpheme in question. Crucially (in the P >> M approach and most other

constraint-based approaches), the separate listed allomorphs of the morpheme are all present in the input, so that even the selection of a special or

dispreferred allomorph satisfies faithfulness constraints. The Italian

example discussed earlier would be modeled as a conflict between, on the

one hand, a set of P constraints relating to stress (perhaps one requiring

exactly one stress per word, in conjunction with one requiring faithfulness

to inherent stress on suffixes), and on the other hand an M constraint such

as Uniform Exponence (Kenstowicz 1996) (11).

(11)

Uniform Exponence: Minimize the differences in the realization of

a lexical item

(morpheme, stem, affix, word)

Both allomorphs of the stem would be present in the input (for “we finish,”

for example, the input would be /{finísk-, fin-}, -iámo /). The ranking P >>

M would select a form with the short stem allomorph (fin-), i.e., fin-iámo.

There is less published work on constraint-based theories of morphology

per se, since the P >> M approach emerged from the OT phonology literature. Therefore there is no definitive statement as to how the OT approach

would handle morphosyntactically or lexically conditioned suppletive

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

104

MARY PASTER

allomorphy. Regarding morphosyntactic conditioning, presumably it would

be conflicts among M constraints (rather than between P and M constraints)

that would yield suppletive allomorphy in an approach along the lines of

the P >> M approach to PCSA. In the case of the Hopi example discussed

above, for example, the M constraint being violated in forms with the special

allomorph might be Uniform Exponence, discussed above. The higherranked constraint forcing violations of Uniform Exponence in plural

words would need to have the function of Pānini’s principle, combining with

_

the specification of the plural stem form with a plural feature to force the

selection of the special plural stem allomorph in plural words where such a

stem allomorph exists. For ease of exposition, let us call this constraint

Special Plural (12), although it may reduce to something more general4

(see also Chapter 17 of this volume for discussion of Pānini’s principle).

_

(12) Special Plural: Use the plural stem allomorph in plural forms.

As in the P >> M approach to PCSA, for other types of suppletive

allomorphy, all listed allomorphs would appear in the input to the tableau

for any word containing the stem in question, such that input-output

faithfulness constraints do not distinguish between candidates containing

one allomorph versus the other. This assumption, combined with the

ranking Special Plural >> Uniform Exponence, would cause the plural

stem to be selected in plural forms (13a) and the elsewhere stem to be

selected in non-plural forms (13b).

(13)

a. momoya-m ‘womenPL’

/{momoyaPL, wùuti}, -mPL/

Special Plural

a. momoya-m

b. wùuti-m

b. wùuti-t ‘womenDU’

/{momoyaPL, wùuti}, -tDU/

a. momoya-t

Uniform Exponence

*

*!

Special Plural

Uniform Exponence

*!

b. wùuti-m

Other analyses are possible in a constraint-based approach depending on

one’s theory. For example, if constraints on inputs are allowed, Pānini’s

_

principle could be considered a constraint on inputs rather than a violable

4

One proposal to capture Pānini’s principle in constraint form is SUBSET BLOCKING (Xu 2007: 80): “An exponent

_

(Exponent1) cannot co-occur with another exponent (Exponent2) if the latter (Exponent2) realizes a subset of feature

values that are realized by the former (Exponent1).” This was proposed to deal with inflectional morphology;

attempting to use this constraint for stem allomorphy seems to backfire. In the present case, SUBSET BLOCKING would only

be satisfied either by choosing the less specified stem or by not expressing the plural suffix, since the plural feature of

the suffix is a subset of the features of the plural stem. If a higher-ranked constraint forced the plural suffix to surface

anyway, this would then force the selection of the less specified stem in order to satisfy SUBSET BLOCKING.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

Alternations: Stems and Allomorphy

105

constraint, such that only the most highly specified stem allomorph that is

compatible with the features of the word as a whole appears in the input.

In this type of model, non-suppletive phonological allomorphy would be

handled using ranked phonological constraints, as in OT phonology and its

relatives. A full explanation of constraint-based analyses of phonological

alternations is of course far beyond the scope of this chapter. One point to

be made here is that a putative advantage of the constraint-based approach

to allomorphy is that the same P constraints are responsible both for PCSA

and non-suppletive phonological allomorphy. This is claimed to be an

advantage because in some languages there are instances of suppletive

allomorphy that appear to be driven by the same phonological considerations as regular phonological alternations and/or phonotactic generalizations in the language. For example, Wolf (2008: 103–5) discusses an

example from Kɔnni (Cahill 2007) where the noun class system appears to

conspire with the regular phonotactics of the language to avoid flaps in

adjacent syllables. No flap-final roots occur in the noun class that has a flapinitial suffix, and in addition, the sequence [ɾVɾ] does not occur within

morphemes. Wolf argues that OT offers a better analysis of this example

than the lexical subcategorization approach does, because the OT analysis

unifies the two phenomena via a single markedness constraint, while the

subcategorization approach would have to treat the two phenomena

separately.

Because the OT approach handles both PCSA and regular phonological

allomorphy (as well as static phonotactics) with the same P constraints in

the same component of the grammar, it predicts that examples of PCSA will

be phonologically “optimizing” (since they are driven by phonological

markedness constraints in this model). This means that the distribution

of allomorphs should be better from the point of view of some phonological

markedness constraint(s) than it would be if the distribution of allomorphs

were reversed. As I have pointed out elsewhere (Paster 2005, 2006, 2009),

and as also noted by Bye (2007), this does not seem to be an accurate

prediction; there are many languages having instances of PCSA that are

not phonologically optimizing in any identifiable way and that apparently

cannot be analyzed using markedness constraints which have been proposed elsewhere in the literature. A well-known example comes from

Haitian creole, where the definite determiner suffix has the form /-a/ after

vowel-final stems and /-la/ after consonant-final stems. As discussed by, for

example, Bye (2007), this distribution of suffix allomorphs is the opposite of

what syllable structure constraints (Onset, NoCoda) would predict.

3.3 Allomorphy Rules and Readjustment Rules

The Distributed Morphology (DM) approach to grammar (Halle and Marantz

1993; see also Chapter 15 of this volume for an overview), like lexical subcategorization, distinguishes between suppletive and morphophonological

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

106

MARY PASTER

allomorphy, but the distinction is made differently. In DM, suppletive allomorphy is modeled via competition between different vocabulary items

(VI; essentially morphemes, including phonological content) for insertion

into syntactic nodes during what is called “spell-out.” The competing

VIs are specified as to the environment (morphosyntactic or phonological)

into which they will be inserted, just as in lexical subcategorization.

Morphophonological allomorphy, where the allomorphs in competition

are phonologically similar, is handled via a single VI being inserted,

followed by the application of readjustment. Readjustment rules are different from phonological rules in being less constrained formally; for example,

where rules in most versions of rule-based phonology can target only a

single segment, readjustment rules in DM can change entire sequences.

Related to the readjustment rule is the allomorphy rule (see, e.g., Aronoff

1976), which changes the segments of a morpheme into another string

of segments in some morphologically defined environment. A possible

critique of both readjustment rules and allomorphy rules is that they are

overly powerful; while “rewrite” rules in phonology have been criticized for

their excessively powerful ability to change any segment into any arbitrarily

different segment in any stable environment (see, e.g., Coleman 1998),

readjustment rules and allomorphy rules have exponentially greater power

since they can target entire sequences of segments. Another drawback of the

allomorphy rule approach that has been discussed in the literature (see, e.g.,

Rubach and Booij 2001) is that it is often not possible to write a rule that

applies in a natural class of environments. Any theory has to acknowledge

that stem allomorphy often occurs in unnatural groupings of morphological environments, but incorporating this fact into an analysis greatly

diminishes the simplicity and elegance of an allomorphy rule, while it is

more straightforward to capture in other approaches like stem indexation,

to be discussed in Section 3.4.

In DM, the Hopi example discussed earlier would presumably be treated as

suppletive allomorphy since the allomorphs are not phonologically similar.

Early statements in the development of DM suggested that roots do not

compete with each other for lexical insertion, but stems do apparently compete. For example, in the analysis of Latin stem allomorphy given by Embick

(2010: 85–6), multiple forms of the verb stem “be” including fu- and es- are in

competition, resolved by fu- being limited to occurring in the perfective form.

Using Embick’s notation, the VIs for the two Hopi stem allomorphs would be

as given in (14), where ‘__ ͡ Num[pl]’ indicates that the momoya allomorph is

limited to the context where it is concatenated with the plural suffix. This VI

will take precedence since it is the more specific of the two.

(14)

[nwoman] $ momoya / __ ͡ Num[pl]

[nwoman] $ wùuti

In contrast to the Hopi nouns, the Germanic strong verbs would be

handled in DM via readjustment rules since the competing allomorphs

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

Alternations: Stems and Allomorphy

107

are more closely phonologically related. See, for example, Embick and

Marantz (2008: 2): “A morphophonological readjustment rule changes the

phonology of give to gave in the context of the past tense morpheme.”

The treatment of PCSA in DM is considered in detail by Embick (2010).

A key feature of DM that is relevant to PCSA is late lexical insertion. In

other theories, affixation and other morphological operations apply to

morphemes whose phonological form is visible to the grammar from the

beginning of the derivation. In DM, most such operations apply in the

syntax to abstract nodes prior to spell-out, meaning that the phonological

content is not yet visible. Under the strongest interpretation of late lexical

insertion, no phonological content would be available to the grammar at

the point of spell-out, meaning that PCSA should not be possible. However,

it has been proposed that spell-out applies cyclically by phase,5 meaning

that phonological material is visible to the grammar if it was spelled out on

an earlier cycle (see Embick (2010) for a detailed articulation of this mechanism). Thus, PCSA is possible when the phonological environment needed

for the insertion of a particular VI is under a node in the same phase or a

phase that triggered an earlier cycle of spell-out, but not in a phase that

will undergo spell-out later in the derivation. This limits the possible types

of PCSA in interesting ways, in that it allows for limited instances of

‘outside-in’ suppletive allomorphy conditioning, where a phonological

property of an affix conditions the selection of an allomorph of an affix

“inside” it (closer to the root) or of the stem itself. The possibility of

“outside-in”-conditioned PCSA has been a point of contention between

proponents of the subcategorization versus constraint-based approaches,

since Paster’s (2006) large cross-linguistic survey of examples of PCSA

revealed no clear cases, while Wolf (to appear) has since identified some

languages that he claims instantiate outside-in conditioning, and Embick

(2010: 61) presents a possible case of outside-in conditioning from

Hupa (Golla 1970) he claims supports the DM approach specifically. (The

generalization in Hupa is that the 1sg subject prefix allomorph e- is used

when preceded by perfective prefix and the verb is non-stative; the prefix

W- occurs elsewhere. If this example holds up, it constitutes outside-in

conditioning since the perfective prefix occurs farther from the root than

the prefix whose allomorphy is sensitive to it.) The Italian example discussed earlier would also be compatible with the DM approach, if it could

be demonstrated that the stem and the inflectional suffixes (whose stress

patterns are claimed to drive the stem allomorphy) are spelled out in a

single cycle.

As with the lexical subcategorization approach, the DM approach and

allomorphy rules do not necessarily specify an approach to regular nonphonological allomorphy.

5

On phases, see Chomsky (2008) and references therein.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

108

MARY PASTER

3.4 Indexed Stems

A final approach to be considered here is the use of stem indexation (see,

e.g., Aronoff 1994). The concept of stem indexation has been incorporated

into multiple different frameworks, including Network Morphology

(Hippisley 1998; see also Chapter 18 of this volume) and Paradigm Function

Morphology (Stump 2001; see also Chapter 17 of this volume). As a result of

the observation that in many languages stem allomorphs are distributed in

unnatural ways, in this model stem allomorphs are indexed such that all

the different stem contexts can be coindexed to match the correct stem

allomorph, obviating the need for the stem itself to bear a list of the

contexts in which it appears.

Following Hippisley’s (1998) notation, a representation of the Hopi

lexeme meaning “woman” in an indexed stem approach might be as in (15).

(15)

WÙUTI

syntax:

noun

semantics:

‘woman’

phonology (stem inventory):

0 /wùuti/; 1 /momoya/

The rules for realizing singular and dual forms would then reference the

stem index 0, while the rule for realizing a plural form would reference the

stem index 1. In this case, the distribution of stem allomorphs could alternatively be characterized as [+plural] versus [-plural], so the advantage of the stem

indexation approach is not as clear as in other examples. The benefits of stem

indexation are more dramatically observable in languages where stem allomorphy occurs in large inflectional paradigms (see, e.g., Stump 2001, Chapter 6

on Sanskrit; Hippisley 1998 on Russian). Essentially, the approach is similar to

lexical subcategorization approach in that morphemes select for other morphemes, but it is different in that affixation is handled by realization rules

here, so the stem is not necessarily present in the representation prior to

affixation, as opposed to the way that words are built from the inside out

under the version of lexical subcategorization that I have described. On the one

hand, this is an advantage of the indexed stems approach if there are examples

of stem allomorphy that cannot be handled by lexical subcategorization; on

the other hand, it is a liability if it turns out that affix-conditioned stem

allomorphy in general is extremely rare (i.e., if Paster’s (2006) findings in the

domain of PCSA turn out to be generalizable to morphologically conditioned

suppletion as well) and all the putative examples turn out to be reanalyzable.

PCSA in stems conditioned by phonological properties of affixes can be

handled in this approach via a “morphological metageneralization” rule

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

Alternations: Stems and Allomorphy

109

(Stump 2001: 180–3). Such a rule would look at all of the realization rules

and could create a set of rules whose output contains affixes with a certain

phonological property (for example, in the Italian case, inherent stress).

That set of affixes would then be subject to a rule referring to a specific

stem index (in the Italian example, the rule for the inherently stressed

suffixes would refer to the index of the fin- allomorph). Note that, as in

the lexical subcategorization approach, the indexed stems/morphological

metageneralization approach treats PCSA as phonologically arbitrary

rather than being driven by phonological markedness. Thus, it has the

same apparent advantage of the lexical subcategorization model in

terms of predicting and being able to account for cases where PCSA

seems to be arbitrary rather than optimizing; on the other hand, it is

vulnerable to the same criticism that proponents of constraint-based

models have leveled against lexical subcategorization, namely that in the

cases of allomorphy that do appear to be optimizing, the model does not

explain the relationship between the choice of allomorph and the conditioning environment.

As with the subcategorization approach and the allomorphy rules/

readjustment rules approach, the indexed stem approach does not necessarily presuppose a particular theory of phonology. Therefore, it does not

appear to prescribe a treatment of non-suppletive allomorphy.

Having demonstrated and evaluated four possible approaches to the

analysis of stem allomorphy, in Section 4 we will discuss remaining problems and issues for future research.

4

Outstanding Issues

In Section 3 we have seen four different theories/frameworks for analyzing

stem allomorphy: lexical subcategorization, constraint-based approaches,

readjustment rules, and indexed stems. For each theory, we have discussed

how the various types of stem allomorphy would be approached. We have

also discussed some advantages and drawbacks of each model. The question

now remains as to which model is superior and ought to be adopted—or, if

some combination of these approaches is indicated, how can they be reconciled with each other in terms of an appropriate division of labor?

As has been discussed, the various models make “cuts” in different places

between different types of allomorphy. In the typology that I presented in

Section 2, there are two basic types of allomorphy: phonological (nonsuppletive) vs. suppletive, defined as involving one underlying form of the

morpheme (in the non-suppletive case) versus two or more (in suppletion).

The version of the lexical subcategorization approach that I have presented

here aligns with this typological division, since non-suppletive allomorphy

is handled by the phonology, while a distinct morphological component of

the grammar is responsible for suppletive allomorph selection.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

110

MARY PASTER

Both the readjustment rules approach and the indexed stems approach

also appear to leave non-suppletive allomorphy to the domain of phonology,

but the readjustment rules approach makes an additional distinction relative to the subcategorization and indexation approaches. With readjustment rules, some cases of suppletion are dealt with as separate underlying

forms that compete for insertion, while some other cases of what the other

two models would deem “suppletion” (and would handle via two separate

underlying forms, whether as separate listed morphemes under subcategorization or as separately indexed stems in a single lexeme under stem

indexation) are treated via a single underlying form. The criterion distinguishing the two cases is phonological similarity: if the two allomorphs are

similar, it is assumed that there is only one basic form of the VI that is

inserted and may then be subject to readjustment rules, which are more

powerful than phonological rules/constraints and can therefore handle

greater variability between surface forms of a single underlying form than

the other two models would tolerate. A major challenge and source of

vulnerability for the readjustment rules approach relative to the other

two is to define what constitutes sufficient phonological similarity to

reduce the allomorphs to a single underlying VI. Presumably the answer

is that they must be similar enough to be relatable via one or more valid

readjustment rules, but this then raises the equally challenging question

of what is a possible readjustment rule. At present, there does not appear

to be any consensus—for example, among practitioners of Distributed

Morphology—regarding a theory of readjustment rules. One could level a

similar critique against the other two models on the grounds that the

decision to analyze allomorphy as suppletive or not depends on a theory

of rules/constraints, but it can be argued that there has been more progress

in this area and that this is not as hard a problem as a theory of readjustment rules. I will take this point up again later.

The constraint-based approach differs from the other three in that it does

not distinguish significantly between PCSA and what the other models

would treat as non-suppletive phonologically driven allomorphy. Both are

handled within a single component of the grammar (which contains both

phonological and morphological constraints). The only difference between

the two phenomena from the point of view of a constraint-based theory is

that in PCSA, all of the different stem allomorphs are present (in curly

brackets) in the input to a tableau, as opposed to non-suppletive allomorphy

where there is only one listed form in the input. This does align with the

idea of separately listed morphemes (in the subcategorization approach),

indexed stems (in the stem indexation approach), or VIs (in the readjustment rules approach), but its effect is very different since the stem allomorphs have equal status in the input for any form that will contain one of

the allomorphs on the surface. For a given case, it is essentially trivial

whether one or multiple underlying forms are posited, since as far as

faithfulness constraints are concerned, whichever allomorph is chosen on

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

Alternations: Stems and Allomorphy

111

the surface will already have been present in the input as if it were selected

in advance. The ability of the constraint-based model to generalize to

morphologically and lexically conditioned suppletive allomorphy will be

determined by the successful development of a constraint-based theory of

morphology. See Caballero and Inkelas 2013 for one recent effort in

this area.

In deciding which model offers a superior approach to allomorphy

(setting aside non-suppletive allomorphy, since of the four models only

the constraint-based approach actually dictates an approach to that type

of allomorphy), considerations of empirical adequacy are relevant. In the

domain of PCSA, as referenced above, there has been a detailed crosslinguistic survey of the phenomenon (e.g., Paster 2006) and considerable

argumentation over details of the cross-linguistic generalizations (see references above), particularly as they relate to the debate between lexical

subcategorization and constraint-based approaches, but more recently the

readjustment rules approach in Distributed Morphology as well. Much of

the debate has concerned (1) whether allomorphy is optimizing and (2)

whether it can be conditioned from the outside in.

Regarding optimization, I and others (Bye 2007; Embick 2010) have

argued elsewhere that being able to capture apparent phonological optimization in PCSA is not an advantage of the constraint-based approach in

light of the fact that not all cases are optimizing. The purported advantage

is entirely self-generated: the theory is claimed to have an advantage in

being able to account naturally and without stipulation for cases that it

treats as optimizing via a theory of optimization, but the fact remains that

this model treats the non-optimizing cases (when they are discussed at all

in the OT literature) via stipulative, language-specific, and sometimes

decidedly unnatural constraints. The superior “explanatory power” of the

model is thus reduced to an ability to explain some subset of the attested

examples, in comparison to other models which are said not to explain any

of them. Thus, this does not in my view constitute a valid argument in favor

of the constraint-based approach. I argue in Paster (to appear) that the

synchronic grammar is not the proper locus for the “explanation” of any

of the patterns, whether they appear on the surface to be optimizing or not.

Regarding the direction of conditioning, I asserted (Paster 2006), extrapolating from results of a cross-linguistic survey of PCSA, that true “outside-in”

conditioning does not exist, meaning that PCSA in stems should not be

conditioned by a property of an affix. Some examples that appeared on the

surface to constitute outside-in conditioning were shown to be reanalyzable.

However, as noted earlier, some examples have since been put forward

that may pose tougher challenges to the claim (see Wolf 2008, 2013;

Embick 2010). A closer look at the details of these examples will determine

whether they do constitute counterexamples. If so, what explains the crosslinguistic rarity of outside-in conditioned PCSA? And is there a strict limit to

the theoretically possible cases (as Embick 2010 proposes) or not? The case

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

112

MARY PASTER

from Sanskrit discussed by Stump (2001: Chapter 6), where verb stem

allomorphs are distributed based on whether the inflectional suffix is

consonant- or vowel-initial, should be added to the list of examples to be

evaluated.

Outside the domain of PCSA, more cross-linguistic research would be

helpful to the analysis of other types of suppletive allomorphy in stems

and more broadly. A broad cross-linguistic search for known cases of

morphologically conditioned stem allomorphy, for instance, would be

useful. Considerable progress on the typology of suppletion has been made

by the Surrey Morphology group (see, e.g., Brown et al. 2004; Chumakina

2004; Corbett 2007). A fuller understanding of the range and parameters of

suppletive allomorphy in the world’s languages will shape the development

of theoretical approaches to the phenomenon.

Setting aside the empirical questions raised above that do not yet have

answers, there are some ways in which the decision among competing

approaches to allomorphy will rely on theoretical argumentation. For

example, it was mentioned earlier that the readjustment rules approach

is lacking a coherent theory of the form and limits of readjustment rules.

Such a theory is needed both for the development of the general theory

(e.g., of Distributed Morphology) and also for the analysis of a given language, since the question of whether a single underlying form or multiple

underlying forms is involved in a given case of phonologically conditioned

allomorphy depends on what readjustment rules can or cannot do. The

related question of what the “regular phonology” of a language can do

(whether in a rule- or constraint-based framework) is relevant to similar

decisions about underlying forms in the lexical subcategorization and

indexed stems approaches. For the lexical subcategorization approach,

I have elsewhere discussed a number of criteria for determining whether

a given case of phonologically conditioned allomorphy is suppletive or not.

Fuller discussion of these is given in Paster (2006: 27–31) (see also Paster

2014), but to restate it briefly here, the criteria are adapted from Kiparsky

(1996: 17):

(16)

Suppletive

A item-specific

B may involve more than one

segment

C obey morphological locality

conditions

D ordered prior to all

morphophonemic rules

Non-suppletive

general (not item-specific)

involve a single segment

observe phonological locality

conditions

follow all morpholexical

processes

Kiparsky does acknowledge that these criteria “cannot claim to provide an

automatic resolution of every problematic borderline case” (1996: 16).

I have argued that criterion (A), involving the generality of the pattern, is

one of the more useful criteria. If a phonological rule needed to analyze a

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

Alternations: Stems and Allomorphy

113

pattern of allomorphy in one morpheme can also account for other patterns

of allomorphy in the language, this suggests that the allomorphy is not

suppletive. On the other hand, if the rule needed to account for a pattern of

allomorphy would only apply to that particular morpheme, then the allomorphy is more likely suppletive.

A related factor is the plausibility of the proposed rule. If the rule is itemspecific but is also formally simple, then this is an argument in favor of nonsuppletive allomorphy. On the other hand, if the proposed rule would be

formally complex (perhaps involving multiple operations or affecting multiple segments simultaneously—thus relating to Kiparsky’s criterion (B)), the

pattern should be analyzed as suppletive. Applying this criterion does

require a commitment to some formal model for which it is clear what

constitutes an allowable operation, trigger, target, and so forth, so that the

plausibility of a rule can be assessed. I have assumed a rule-based phonology

that includes autosegmental representations and extrinsic rule ordering,

though what I have said here may be compatible with a wide variety of

approaches to phonology.

Any model of allomorphy will have to be paired with its own statement of

criteria for distinguishing between types of allomorphy. A comparison

among models could then be based in part on theoretical argumentation

regarding how powerful a phonological system is required by each model

and the plausibility of such a model.

5

Conclusion

In this chapter, I have presented an overview of the logically possible types

of stem allomorphy, giving examples of each type. I have discussed four

different theoretical approaches to stem allomorphy and shown how each

would deal with the different types of allomorphy. In the preceding section,

I have compared some features of the different approaches and discussed

how further empirical research and/or theory development might help to

distinguish among them.

In some respects, the choice of theoretical approaches to allomorphy may

be a subject on which there will never be consensus. Some of the four

approaches discussed in this chapter are radically different from each

other, and of course these four do not represent the full range of possible

approaches that exist in the literature or could be proposed. It is daunting

to imagine finding common ground among them, and perhaps it is

tempting to remain agnostic or to continue working within one’s own

theory while allowing that other models may also have their advantages

and may be scientifically useful theories in the way that they inspire new

research and thinking. On the other hand, the decision as to which

approach to take is important not only in itself but in some cases in much

larger questions about the nature of human language. For example, the

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

114

MARY PASTER

constraint-based approach treats phonology and morphology as part of a

single component of the mental grammar, while the lexical subcategorization approach treats them as crucially distinct from each other, and the

realization rules approach within Distributed Morphology conceives of the

division among components of the grammar in yet another radically different way. Thus, while it may be difficult to demonstrate the superiority of

one approach over another, the effort to do so is crucial to advancing our

understanding of human language.

References

Aranovich, Raúl; Sharon Inkelas, Orhan Orgun, and Ronald Sprouse. 2005.

Opacity in phonologically conditioned suppletion. Paper presented at

the 13th Manchester Phonology Meeting.

Aronoff, Mark. 1976. Word Formation in Generative Grammar. Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press.

Aronoff, Mark. 1994. Morphology by Itself. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Brown, Dunstan; Marina Chumakina, Greville G. Corbett, and Andrew

Hippisley. 2004. The Surrey Suppletion Database. [Available online at

www.smg.surrey.ac.uk.]

Bye, Patrik, 2007. Allomorphy: selection, not optimization. In Sylvia Blaho,

Patrik Bye, and Martin Krämer (eds.), Freedom of Analysis? Studies in

Generative Grammar 95, 63–91. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Caballero, Gabriela, and Sharon Inkelas. 2013. Word construction: Tracing

an optimal path through the lexicon. Morphology 23.2, 103–43.

Cahill, Michael C. 2007. Aspects of the Morphology and Phonology of Kɾnni.

Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Robert Freidin, Carlos Peregrín Otero,

and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta (eds.), Foundational Issues in Linguistic Theory:

Essays in Honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, 133–66. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chumakina, Marina. 2004. The notion ‘possible word’ and its limits:

A typology of suppletion. An annotated bibliography. [Available

online at www.surrey.ac.uk/LIS/SMG/Suppletion_BIB/WebBibliography

.htm (accessed March 14, 2016).]

Coleman, John. 1998. Phonological Representations: Their Names, Forms and Powers.

Cambridge Studies in Linguistics, number 85. Cambridge University Press.

Corbett, Greville G. 2007. Canonical typology, suppletion and possible

words. Language 83.1, 8–42.

Da Tos, Martina 2013. The Italian FINIRE-type verbs: A case of morphomic

attraction. In Silvio Cruschina, Martin Maiden, and John Charles Smith

(eds.), The Boundaries of Pure Morphology: Diachronic and Synchronic Perspectives, 45–67. Oxford University Press.

DiFabio, Elvira G. 1990. The Morphology of the Verbal Infix isc in Italian

and Romance. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

Alternations: Stems and Allomorphy

115

Embick, David. 2010. Localism versus Globalism in Morphology and Phonology.

Linguistic Inquiry Monographs 60. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Embick, David, and Alec Marantz. 2008. Architecture and blocking. Linguistic Inquiry 39.1, 1–53.

Golla, Victor. 1970. Hupa Grammar. Ph.D. dissertation, University of

California–Berkeley.

Hall, Robert A. 1948. Descriptive Italian Grammar. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press and Linguistic Society of America.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed Morphology and the

pieces of inflection. In K. Hale and S. J. Keyser (eds.), The View from

Building 20: Essays in Honor of Sylvain Bromberger, 111–76. Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press.

Haugen, Jason D., and Daniel Siddiqi. 2013. Roots and the derivation.

Linguistic Inquiry 44.4, 493–517.

Hill, K. C., and M. E. Black. 1998. A sketch of Hopi grammar. In The

Hopi Dictionary Project (eds.), Hopi Dictionary: Hopìikwa Lavàytutuveni:

A Hopi-English Dictionary of the Third Mesa Dialect, 861–900. Tucson:

University of Arizona Press.

Hippisley, Andrew. 1998. Indexed stems and Russian word formation:

A Network Morphology account of Russian personal nouns. Linguistics

36, 1039–1124.

Inkelas, Sharon. 1990. Prosodic Constituency in the Lexicon. New York: Garland

Publishing.

Kenstowicz, Michael. 1996. Base-Identity and Uniform Exponence: Alternatives to cyclicity. In J. Durand and B. Laks (eds.), Current Trends in

Phonology: Models and Methods, vol. 1, 363–93. Salford: ESRI.

Kiparsky, Paul. 1982. Word-formation and the lexicon. In Frances

Ingemann (ed.), 1982 Mid-America Linguistics Conference Papers, 1–29.

Lawrence: Department of Linguistics, University of Kansas.

Kiparsky, Paul. 1996. Allomorphy or morphophonology? In Rajendra

Singh, ed., Trubetzkoy’s Orphan: Proceedings of the Montreal Roundtable

‘Morphophonology: Contemporary Responses,’ 13–31. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Lewis, Geoffrey L. 1967. Turkish Grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lieber, Rochelle. 1980. On the Organization of the Lexicon. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Maiden, Martin. 2004. When lexemes become allomorphs: On the genesis

of suppletion. Folia Linguistica 38.3–4, 227–56.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1993a. Generalized alignment. Yearbook

of Morphology 1993, 79–153.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1993b. Prosodic Morphology I:

Constraint interaction and satisfaction. Unpublished manuscript,

University of Massachusetts, Amherst and Rutgers University.

Orgun, Cemil Orhan. 1996. Sign-Based Morphology and Phonology with

Special Attention to Optimality Theory. Ph.D. dissertation, University

of California–Berkeley.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Bill To for 21002 Zurich Uni), on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:38:59, subject

to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139814720.005

116

MARY PASTER

Paster, Mary. 2005. Subcategorization vs. output optimization in syllablecounting allomorphy. In John Alderete et al. (eds.), Proceedings of the

24th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, 326–33. Somerville, MA: