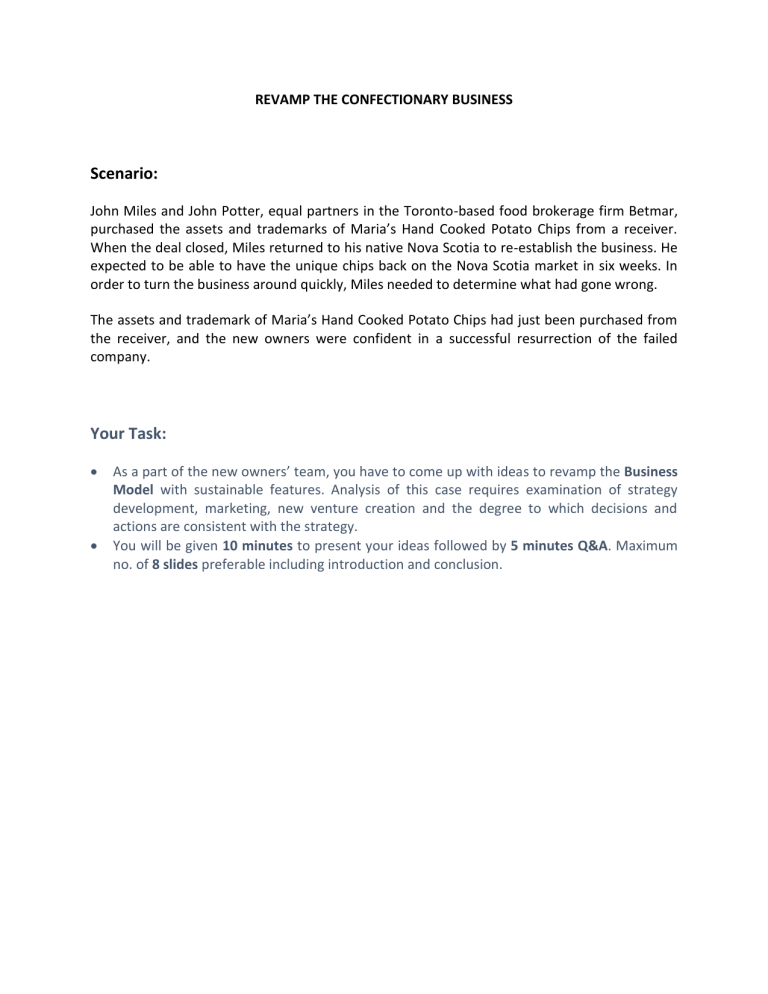

REVAMP THE CONFECTIONARY BUSINESS Scenario: John Miles and John Potter, equal partners in the Toronto-based food brokerage firm Betmar, purchased the assets and trademarks of Maria’s Hand Cooked Potato Chips from a receiver. When the deal closed, Miles returned to his native Nova Scotia to re-establish the business. He expected to be able to have the unique chips back on the Nova Scotia market in six weeks. In order to turn the business around quickly, Miles needed to determine what had gone wrong. The assets and trademark of Maria’s Hand Cooked Potato Chips had just been purchased from the receiver, and the new owners were confident in a successful resurrection of the failed company. Your Task: As a part of the new owners’ team, you have to come up with ideas to revamp the Business Model with sustainable features. Analysis of this case requires examination of strategy development, marketing, new venture creation and the degree to which decisions and actions are consistent with the strategy. You will be given 10 minutes to present your ideas followed by 5 minutes Q&A. Maximum no. of 8 slides preferable including introduction and conclusion. MARIA’S HAND COOKED POTATO CHIPS In March, 1990 John Miles had a wealth of experience in the confectionary business, having spent 23 years with Nabisco Brands as a sales manager and national account representative. After leaving Nabisco, Miles started Betmar, a brokerage company, with partner John Potter of the sales promotion company Nash Potter. Potter was the idea man and Miles made things happen. Betmar was the successful bidder for the assets of Maria’s: the machinery, a computer, the trademarks and a few supplies. The plant was not in working order, as the packaging machine had been repossessed in January, 1989 due to a default on payments. In addition, the registration of the trademarks had never been completed, so the brand names were not legally protected. Betmar was to be a source of working capital for the first year. Upon arriving at the plant, Miles discovered that there were no records or files and that he would have to try to understand what had gone wrong using only limited information. Based upon recent newspaper articles, previous conversations with Brian Shore (the former owner of Maria’s), and interviews with former employees and retailers, Miles was able to piece together the following chronology of events. Maria’s was founded in 1984 by Brian Shore, a 38 year old law school drop-out who was a natural salesman. Shore had a history of entrepreneurial activity including building and selling prefabricated homes and producing New York-style soft pretzels which he sold from vending carts. The new company was set up under Mazel Mining Co., an existing Shell company. This would enable Shore to use what little cash he had for the down payment on a delivery vehicle, a '79 Oldsmobile with the rear seat removed. Shore had been looking for a product which would generate revenue even in hard economic times. He turned to snack foods, stating: "When people don't have a lot of money, they buy a bag of chips and a six-pack of beer and go home and watch the hockey game rather than go out to a nightclub". Financing had been through a $30,000 loan from a silent partner (who left the business in March 1985), a $64,000 loan from the Toronto Dominion Bank (five other banks refused) and a $100,000 federal government small business loan. Canadian retail potato chip sales in 1984 were $500 million and had been experiencing an annual growth rate of 5%. The highly competitive industry was dominated by three national producers: Hostess Food Products (General Foods), Humpty Dumpty (American Brands) and Frito-Lay (PepsiCola Canada). Shore commented, "I thought if I could get 2% of the industry, I would have a hell of a business". The Maria’s chip was based on a 75-year-old Pennsylvanian Mennonite recipe which Shore altered to suit his taste. Conventional chip production used a continuous process where the potatoes were peeled using caustic soda, sliced, then dipped in a chemical bath or boiling water to bleach out the colour and finally fried in oil. Maria’s used a batch process, slicing the chips directly into an open vat fryer and cooking them at a lower temperature for a longer time. The chips were hand stirred and the cooking time was determined by sight. "Our people get used to knowing when they're ready", said Philip Morris, Maria’s production manager. No preservatives or monosodium glutamate were added and sunflower oil was used to make the chips cholesterol free. The result was a thicker, crispier, more nutritious and flavored chip. Maria’s was the only company with a hand cooked chip on the Canadian market. The name "Maria’s" came from Shore's partner's wife. Shore designed the white, red and blue package which pictured a woman with piled hair wearing a long dress and apron, stirring a cooking kettle with a ladle. The bag boasted "Natural Ingredients" and stated, "Maria’s Hand Cooked Chips are made the old-fashioned way - hand cooked one batch at a time. This original method produces a potato chip that is golden crisp and crunchy with that tremendous natural potato flavor". Said Shore, " 'Naturals', like Maria’s, have become a 'yuppie' product- they've developed a cult following". And, "I just figured that if I made a different potato chip, I'd get a niche in the market". Maria’s chips cost about 20% more to produce than conventional chips, but Shore felt, "If people like a product, they'll willingly pay a premium for it". The suggested price to the consumer was similar to national producers' prices but Maria’s packages were smaller. 1984 - THE BEGINNING Shipments from the 3,500-sq.-ft. north-end Halifax plant, described by Shore as "a dump with a leaky roof", began in November 1984. Maria’s offered three varieties: regular, Bar-B-Q and no salt. Two package sizes were available: a 32 gram snack pack (national producers used 48 grams) and the regular 180 gram bag (national producers used 200 grams). Shore spent no money on advertising but gave a lot of chips away hoping to generate word-of-mouth: "We don't need all the new and improved hoopla. If the people like it, they'll buy it, and they'll create the demand". The only promotion of Maria’s chips was Shore's sales efforts. Said Shore, "We're purposely being unsophisticated, not hiring marketing guys and whatever". 1985 - MODEST GROWTH Shore sold to health food stores, student pubs, and independent grocery and convenience stores in the Halifax-Dartmouth area because he had difficulty getting his product into the large grocery and convenience chain stores. He felt the chain stores should be obligated to stock a local product, and refused to negotiate shelf allowances in order to get listings. It was common trade practice for grocery retailers to expect incentive payments from manufacturers. Allowances lowered a retailer's costs and paid for in-store promotions and store advertising which featured the manufacturer's product. Shore fought tradition because he believed allowances discriminated against smaller companies with limited financial resources. Unable to achieve wide distribution, he began to look beyond the Maritime region for opportunities. In early 1985, Shore thought of producing a kosher chip for the annual Jewish religious holiday, Passover. He approached Steinberg's in Montreal, one of Quebec's largest grocery chains, and received a $30,000 order. By the end of 1985, Maria’s was shipping chips throughout Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, and ended the year with sales of $500,000 and a profit of almost $20,000. 1986 - RAPID GROWTH The year 1986 brought tremendous consumer acceptance for the chips and growth for Maria’s. Listings were obtained in the large grocery chains: Sobey's, The Food Group and IGA. This move expanded distribution to Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. In order to increase volume, Shore positioned Maria’s as the low-priced competitor. Moreover, prices were occasionally reduced further during selected promotional periods, and Maria’s was often used by some retailers as a low price promotion. Due to the large number of retail accounts in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, Maria’s contracted with independent general-line wholesalers to merchandise its product in major markets outside the Halifax-Dartmouth area (Fredericton, Moncton, and Saint John in New Brunswick; Truro, Bridgewater, Sydney and the Annapolis Valley in Nova Scotia). Merchandising entails order taking, delivering the chips, placing them on the rack in a presentable fashion and rotating the older chips to the front. The wholesalers received minimal direction and attention from Maria’s. In contrast to Maria’s, national producers used company vehicles operated by trained company employees. Maria’s made a number of changes in response to the growing demand for the product. It installed a new $200,000 form-filled packaging machine to speed up production. The product line was broadened to include "salt and vinegar" and "sour cream and onion", and the original snack bag was increased in size to 42 grams. In spite of $2 million in annual sales, Maria’s barely broke even in 1986. 1987 - EXPANSION In 1987 Maria’s received its first large national order. It was unexpected, and had been prompted by a small order to a local store in the Zeller's chain which had put Maria’s on the supplier's list. A few months later, the president of Zeller's sent a letter to all suppliers soliciting funds for a charity. Shore replied with product samples and a letter stating if he had a contract he would be able to afford a donation. This resulted in an order for 500,000 bags and many of the stores sold out in two weeks. Internationally, Maria’s received an order from a Taiwanese food importer whose representatives visited the plant and then ordered a container of chips (40,000 bags) six months later. The sale of the building rented by Maria’s provided an opportunity for expansion. Based on Shore's forecasted sales of $10 -15 million in the next two years, Maria’s moved into a $1.3 million, 17,000 sq.-ft. plant across the harbor in Dartmouth's Burnside Industrial Park. The move was financed by a $250,000 loan from the Small Business Development Corporation, and accomplished during a two month summer shutdown caused by a potato shortage. Shore perceived the need to compete in the conventional potato chip market, so the company launched a thinner chip called "Archie's." It gained wide distribution and was pegged at a price lower than the national producers' products. By the end of the year, Shore had appeared on the CBC's business program "Venture", was negotiating a national contract with Boots Drug Stores, and was looking at the European and Asian markets. The company's annual sales were $3 million and it employed 35 people. 1988 - THE DEMISE In 1988, consumer loyalty for the locally produced chip remained strong even though the chips had become increasingly greasy. Maria’s had been trying to maximize the use of the frying oil to reduce costs, but had no way of testing the oil's quality. By mid-year sales had slowed. The situation worsened when Maria’s became caught in the cross fire of a price war between the national producers. Stated Shore, "If they want to shoot cannons at a mosquito they can, but they will make a mess of the wall." In addition, the federal government introduced a sales tax on snack foods which increased the price of chips to the consumer. Distribution in the Maritimes became spotty when some of the wholesalers dropped the product due to falling sales. Shore continued to look for expansion in the Ontario market and approached John Miles to act as the Ontario broker. After a number of meetings, a tentative agreement was reached between the two parties. By year end, Shore was not returning Miles's phone calls and by January 1989, no one was answering at Maria’s until one day Miles's call was answered by a representative of Touche Ross, the receiver.