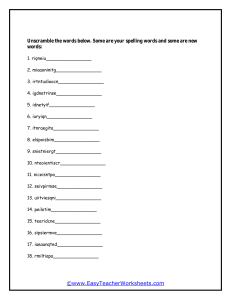

This article was downloaded by: [UQ Library] On: 12 November 2014, At: 18:46 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Reading Research and Instruction Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ulri19 Developing first graders' phonemic awareness, word identification and spelling: A comparison of two contemporary phonic instructional approaches Laurice M. Joseph a a The Ohio State University Published online: 28 Jan 2010. To cite this article: Laurice M. Joseph (1999) Developing first graders' phonemic awareness, word identification and spelling: A comparison of two contemporary phonic instructional approaches, Reading Research and Instruction, 39:2, 160-169, DOI: 10.1080/19388070009558318 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19388070009558318 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. Downloaded by [UQ Library] at 18:46 12 November 2014 This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-andconditions Reading Research and Instruction Winter 2000, 39 (2) 160-169 Developing first graders' phonemic awareness, word identification and spelling: A comparison of two contemporary phonic instructional approaches Laurice M. Joseph The Ohio State University Downloaded by [UQ Library] at 18:46 12 November 2014 ABSTRACT This exploratory study compared the effectiveness of two contemporary phonic approaches (word box instruction and word sort instruction) on children's phonemic awareness, word identification, and spelling performance. Forty-two first-grade children who were randomly selected to participate in three conditions: word box instruction, word sort instruction, and traditional instruction. The experimental conditions lasted approximately three months and consisted of daily 20 minute phonics instruction sessions. Children were administered five posttest measures: phonemic blending, phonemic segmentation, pseudo-word naming, word identification, and spelling. MANOVA and univariate analyses revealed that type of phonic instruction significantly discriminated among the groups on posttest measures. Post hoc analyses indicated that there were significant differences favoring (1) word box instruction group over the traditional group on performance on all posttest measures except spelling, and (2) word sort group over control on phonemic segmentation, word identification and spelling performance. No significant differences existed between the two experimental conditions on any measure. Very few quibble over whether phonics should be taught as part of a comprehensive classroom literacy program. Instead, many have suggested that it should be taught well (Adams, 1990; Chali, 1996; Groff, 1998; Williams, 1991). The question that still remains is what constitutes teaching phonics well? In a recent article about teaching phonics, Stahl, Duffy-Hester, & Stahl (1998) present a comprehensive overview of specific contemporary phonic instructional approaches. Contemporary phonic instruction approaches are different than traditional approaches because they incorporate word study procedures involving multi-sensory manipulatives to help children internalize phonological and orthographic features about words. Traditional phonics instruction tends to be rule-based and involve many worksheet assignments. Although contemporary phonic approaches appear to have the potential for being more engaging to the learner as well as including phonemic awareness training and spelling, their effectiveness has not been demonstrated through comparative, controlled research studies (Stahl et al., 1998). The purpose of the present study was exploratory as it sought to compare the effectiveness of two contemporary phonic instructional approaches on first-grade children's' phonemic awareness, word identification, and spelling performance. The two contemporary phonic instructional approaches studied were word boxes instruction and word sort instruction. These two approaches have the potential to facilitate the linkages between phonemic awareness, word identification, and spelling; but they have not been compared to traditional phonic instruction in determining their effectiveness Downloaded by [UQ Library] at 18:46 12 November 2014 161 Reading Research and Instruction Winter 2000, 39 (2) on first-grade students' early literacy performance. Word boxes, an approach used within the comprehensive Reading Recovery program (Clay, 1973), are an extension of D.B. Elkonin's (1973) sound boxes because they go beyond segmenting sounds in spoken words. Word boxes also involve matching sound to print as children articulate sounds in words while placing magnetic or tile letters and writing words in the boxes. Specifically, a word box consists of a drawn rectangle that has been divided into sections (boxes) according to individual phonemes in a word. Initially, the child places a token in respective sections as each sound in a word is articulated slowly. Eventually, the child places letters (either magnetic or tile) in respective sections as each sound in a word is articulated. During more advanced phases, the child is asked to write the letters in the respective divided sections of the box. Griffith & Olson (1992) and Yopp (1995) have described word boxes as a good approach to helping children develop phonemic awareness. Variations of this approach have been used as part of a comprehensive phonemic awareness training program in experimental studies (e.g., Ball & Blachman, 1991; Hohn & Ehri, 1983). Using single subject designs, Joseph (1998) demonstrated its effectiveness for helping second-grade and third-grade children with learning disabilities identify and spell basic words. Word sorts have been considered to be a contemporary spelling based phonic instruction approach (Stahl et al, 1998). According to Bear, Invemizzi, Templeton, and Johnston (1996), word sorting is a technique that can be used to help children categorize words according to shared phonological, orthographic, and meaning structures. Word sorts can come in the form of closed sorts in which the teacher establishes the categories or open sorts in which the child induces the categories based on an examination of subsets of given words to be sorted (Zuteil, 1998). Words to be sorted are usually placed on index cards, and the established categories provide a structure for detecting common spelling patterns and discriminating among word elements (Barnes, 1989). Although word sorts have not been researched extensively (Zuteil, 1998), studies have shown word sorts to be especially effective for helping children in the upper primary and intermediate grades make gains in spelling performance (Hall, Cunningham, & Cunningham, 1995; Weber & Henderson, 1989; Zuteil & Compton, 1993). Word sorts have also been used within various tutoring programs. Morris, Shaw, and Perney (1990) used word sorts to help second and third grade children recognize and spell word patterns within a comprehensive tutoring program called the Howard Street Tutoring Program. Children who received tutoring made greater gains in reading and spelling than a comparison group of children who did not receive tutoring. Santa and Hoien (1999) implemented the Early Steps tutoring program with a sample of first-grade children. Word sorts were used as a method for studying word patterns in this program. Children who received the Early Steps program performed significantly better in spelling and word recognition than children in a control group. The present study explored the following specific research questions. 1) Will first-grade children who receive word boxes or word sort instruction (two contemporary phonic approaches) outperform first-grade children who receive traditional phonic instruction on measures of phonemic awareness, word identification, and spelling? Comparing Phonic Approaches 162 2) Will word box and word sort instruction produce differential effects on first-grade children's phonemic awareness, word identification, and spelling performance? METHOD Downloaded by [UQ Library] at 18:46 12 November 2014 Participants Participants in this study consisted of 42 Caucasian first-grade children from two first grade classrooms (age range = 6.2 to 7.3, mean = 6.6). The total sample was comprised of 19 females and 23 males who were Caucasian. Parent permission to participate in this study was obtained for all 42 students. Children attended a public school in a suburban Southwest Ohio school district. The children came from families of low to lower-middle socioeconomic levels. Instructor A teacher educator with a specialization in literacy implemented both word box and word sort lessons. The instructor received training on both approaches. Procedures Forty-two children from two first grade classrooms were randomly selected to participate in one of three experimental conditions: word box instruction, word sort instruction, and a control condition (traditional classroom instruction). There were 14 students in each group. The word box group was comprised of 6 females and 8 males (age range = 6.2 to 7.2, mean = 6.6). There were also 6 females and 8 males in the word sort group (age range = 6.3 to 7.3, mean = 6.7). The control group consisted of 7 females and 7 males (age range = 6.3 to 7.2, mean = 6.6). All students were administered the Letter-Word Identification subtest of the Woodcock-Johnson Achievement Battery-Revised to obtain initial performance levels on word recognition prior to implementation of contemporary phonic approaches. Table 1 presents means and standard deviations of Letter-Word Identification performance by group prior to the implementation of contemporary phonic approaches. Differences on Letter-Word Identification performance among groups prior to contemporary phonic instruction were determined by a one-way ANOVA. No significant differences were found among the groups on Letter-Word Identification performance (F (2,39)=.0001 p=.99. There was similar variability in Letter-Word Identification performance within groups. TABLE 1 Means and standard deviations of pretest performance by instructional group LETTER-WORD IDENTIFICATION Group Word Box Word Sort Traditional Total n 14 14 14 42 M 92.28 92.21 92.29 92.26 SD 14.30 13.18 12.06 12.88 163 Reading Research and Instruction Winter 2000, 39 (2) Downloaded by [UQ Library] at 18:46 12 November 2014 Students were subjected to the respective conditions for 50 daily sessions excluding holidays over a 12 week period beginning in September and lasting until December of the 1998 school year. Students who were selected to participate in experimental instructional conditions were removed from their classroom during phonics instruction time only and were able to participate in contextual reading time in their first-grade classrooms. Selection of Words Taught Words selected to be taught during instructional lessons in all conditions were phonograms containing consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) patterns. A complete list of the words that were used can be found in Figure 1. Words with CVC patterns were chosen because most children had not mastered identifying and spelling these types of words. Children in all three conditions were instructed on approximately 6 to 10 words per day from the list of words. In all three conditions a new word family was presented approximately every week. Some weeks two word families were presented. Words previously taught in one session were reviewed in another session in accordance with type of instructional approach. FIGURE 1. List of phonograms used in this study. sit bit can man wit kit fit hit pit tan fan pan ran van mop top hop pop big dig fig Pig wig cat fin pin hut cut map cap sat fat bat hat pat rat kin sin tin win but gut nut tap gap lap nap tap zap sun dip hip lip sip pet set met bet get jet let net vet wet dot got hot lot not pot rot mat run fun bun gun tip zip ; Experimental Condition Word box and word sort instructional lessons employed a scaffolding approach. For instance, the instructor provided demonstrations, guidance, and feedback until students were able to function on their own. Scaffolds were also embedded within the tasks. In other words, tasks' materials were intended to be used (e.g., divided sections of the word box, chips, magnetic letters, word categories, and note cards) as supportive structural components for identifying and spelling words. Both experimental conditions and control condition are subsequently described in more detail. Downloaded by [UQ Library] at 18:46 12 November 2014 Comparing Phonic Approaches 164 Word Boxes Children who participated in the word boxes condition received 20 minute daily lessons. Each student was provided with a magnetic board that contained a drawn rectangle divided into three sections. Each section corresponded to the individual sound units in words. Approximately 6 to 10 words were presented with the exception of the initial sessions. Four words were provided initially to allow children the chance to grasp the process of the task. To facilitate the links between phonemic awareness, phonological recoding, and orthographic processing, an entire daily word box lesson was presented in three stages. The instructor initially demonstrated all three stages to the children, shared the task with the children, and gradually allowed the children to perform the task independently with guidance. The first stage facilitated awareness of phonemes by providing the children with three colored chips in which each one was to be placed below a section of the divided rectangle. As the instructor slowly articulated sounds in a word, the children were asked to place the chips sequentially in respective divided sections of the drawn rectangle. Children were then asked to slowly articulate the sounds in a word as they placed the chips sequentially in respective divided sections of the box. The second stage consisted of facilitating phonological recoding. In the second stage, the chips were replaced with magnetic letters and children were asked to place them in respective divided sections of the rectangle as they slowly articulated sounds in words. Children were asked to write the letters in the divided sections using a magic marker as they articulated sounds slowly. This was considered the final stage and it was mainly intended to more explicitly facilitate orthographic knowledge about words (spelling patterns). Each child was given a tissue to wipe the written letters off before the next word was articulated. Word Sort Children who participated in the word sort condition were also provided with 20 minute daily instruction. Three small index cards were placed in a horizontal fashion in front of the students at their table. Each index card contained a written word (e.g., cat, man, fit). Each word designated a category. To ensure that the children could identify the categorical words, the instructor and the children would chorally read all three index cards. An entire word sort lesson was also designed to facilitate the links between phonemic awareness, word recognition and orthographic processing. The first stage consisted of facilitating phonemic awareness by providing several chips that were placed on the table. The instructor would say a word, and the children were required to place a chip below one of the word categories represented by index cards. Once the child placed a chip below a category, the instructor provided the child with an index card with the word written on it and the child removed the chip, and placed the new index card below the one that establishes the category. This provided a means for the child to verify his response and self-correct if the chip was placed in the wrong category. After a number of words were phonemically sorted, all the previously sorted index cards with the exception of those used to establish categories were shuffled and stacked. 165 Reading Research and Instruction Winter 2000, 39 (2) Downloaded by [UQ Library] at 18:46 12 November 2014 In this second stage, Children were required to sort the pile of words according to common spelling patterns ( sometimes referred to as a visual sort) as designated by the categorical words. Upon completing the sort, children were asked to read the words below each category which also provided a means to verify responses and self-correct. The third stage consisted of having the students perform a spelling sort. Children were provided a piece of white paper with each category word written across the top. The instructor would say a word, and the children were asked to spell the word below each respective category. The words varied across sessions. Control Children who participated in the control condition received traditional classroom instruction provided by their first-grade teachers. Their first-grade teachers provided instruction on phonograms. Each day, they would write a list of words that shared similar spelling patterns on an overhead transparency, and the children would engage in repeated choral readings of those words. Sometimes choral readings would be followed with an explanation of the meaning of words and using words in sentences. Once words were read on the overhead, the teacher would place the list of words on a long roll of white paper and hang it on the wall so children could view it throughout the day. Additional rolls of paper were added to the ones already hanging on the wall as children were introduced to a new phonogram. The teachers would also assign phonogram workbook exercises and teacher-made worksheets. Very limited, if any, direct instruction on spelling words was provided. Some workbook exercises and teacher-made worksheets involved writing the words as well as cutting and pasting, and drawing circles around words. Dependent Measures All posttest measures were administered individually to the children in a quiet room suitable for testing. Posttests are subsequently described, and they consisted of phonemic awareness, word identification, pseudoword naming, and spelling measures. Phonemic awareness Phonemic Segmentation and Phonemic Blending subtests of the Phonological Awareness Test (Robertson & Salter, 1997) were used to assess students' phonemic awareness. During the administration of the Phonemic Segmentation subtest, children were asked to segment each sound in words that were spoken by the examiner. Each item contained a word that was read by the examiner. The student was required to say each sound in the word presented by the examiner. For instance, the examiner said the word "cat" and the student said Id Izl IM. On the Phonemic Blending subtest, children were asked to blend sounds of words and say each word as a whole. Each item contained a word broken into segments such as /s/ lui In/. The examiner said each sound in the word and the student was asked to blend the sounds and say the word "sun" as a whole. Standard scores were derived from each of the subtests on this norm-referenced measure. Word identification A list of 60 words (phonograms) containing CVC patterns was randomly placed Comparing Phonic Approaches 166 (i.e., not placed according to their phonogram or word family category) on two sheets of white paper. Children were asked to read the words on the paper. Total number correct was recorded for each child. Downloaded by [UQ Library] at 18:46 12 November 2014 Pseudoword naming Word Attack subtest from the Woodcock-Johnson Achievement Battery-Revised (Woodcock & Johnson, 1989) was used as a measure of pseudoword naming. Children were asked to read a list of nonsense words. This was a norm-referenced measure from which standard scores were derived. Spelling Twenty words were randomly selected from all phonograms (CVC patterns) taught. The instructor said a word and the student was required to write it on a plain piece of white paper that was numbered from 1 to 20. Total number correct was recorded for each child. DATA ANALYSIS Means and standard deviations were obtained on children's performance on posttest measures. MANOVA and univariate statistical procedures were calculated to determine overall significance of the model. Schefee' tests were used as post hoc analysis to determine significant differences between groups on all posttest measures. RESULTS Means and standard deviations on all posttest measures are presented in Table 2. A mutivariate test revealed that type of instruction significantly separated the three groups (Wilks Lambda = .43, F (2,39)= 3.66, p<.001). The five posttest measures were subjected to analysis simultaneously, the generalized proportion of variance among the groups which they explained was 34% (MANOVA T)2 = .344). Univariate procedures revealed that all five measures significantly discriminated among the three groups: phonemic blending F (2,39)=4.91, p<.01; phonemic segmentation F (2,39)=11.67, /K.001 ; pseudo-word naming F (2,39)=11.36,/K.Ol ; word identification F (2,39)=11.36, /K.001; and spelling F (2, 39)=6.21,p<.01. TABLE 2 Means and standard deviations of posttests performance by instructional group GROUP* Posttest Phonemic segmentation Phonemic blending Pseudoword naming Word identification Spelling Word Box M SD 119.64 111.71 106.92 55.71 16.50 9.80 5.34 7.89 4.41 2.62 Word Sort M SD 112.50 15.45 108.35 6.24 103.92 11.14 47.14 15.17 18.00 2.54 Traditional M SD 95.92 102.21 94.14 33.92 13.07 14.04 11.43 14.04 13.98 5.45 Total** M SD 109.35 107.42 101.66 45.59 15.85 Note *n=14 participants per instructional group **n=42 total participants Standard scores were obtained on all measures with the exception of word identification and spelling and were based on a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. Raw scores were obtained for word identification (60 possible points) and spelling (20 possible points). 11.61 8.87 12.34 14.94 4.24 Downloaded by [UQ Library] at 18:46 12 November 2014 167 Reading Research and Instruction Winter 2000, 39(2) Phonemic blending and phonemic segmentation total scores accounted for 20% and 37%, respectively, of the variance among the three groups. Word identification and pseudo-word naming total scores accounted for 36% and 20%, respectively, of the variance among the three groups. Variance among the three groups explained by total score in spelling was 24%. Results of the Scheffe' post hoc test of significance for multivariate multiple group comparisons on each posttest measure were also calculated. Significant mean differences were found in favor of the word box instructional group when compared to the control group on phonemic blending (p<.01); phonemic segmentation (p<.001); pseudoword naming (p<.05); word identification (p<.001 ). Significant mean differences were found in favor of the word sort instructional group over the control group on phonemic segmentation (p<.01), word identification (p<.05), and spelling (p<.0l). There were no significant differences found between word box instructional group and word sort instructional group on all posttest measures. Differences in performance among posttest measures between the two contemporary phonic instructional groups that came close to approaching significance atp=.05 were in the measure of spelling. Word sort group performed better than the word box group at p<. 10. DISCUSSION Contemporary phonic instruction approaches used in this study appear to have merit in regards to producing desirable basic literacy performance for a sample of firstgrade children. These approaches appear not only to influence changes in performance on word identification tasks but also produced changes in performance on phonemic awareness tasks. Word sort instruction has often been coined a spelling-based phonic approach (Stahl et al, 1998). Consistent with previous findings, it appeared to be especially viable for helping this sample of first-grade children spell words accurately. However, word sorts are not only used to improve spelling performance but also used to develop word recognition skills (Morris, 1982). In the present study, word sorts were also effective for helping a sample of first-grade children identify words. Children in the word box condition demonstrated better phonemic segmentation, phonemic blending, pseudoword naming, and word identification skills compared to the children in the traditional phonics condition. The sequential processing demands of the word box approach provide a likely reason for children's success in segmenting phonemes and making successive letter-sound correspondences. While word boxes and word sort approaches were effective for improving children's early literacy skills, it should be noted that children in the word sort condition displayed more frequent strategic self-monitoring and self-correcting behaviors. The established categories makes it relatively easy for children to verify and correct their responses as they sort words (Zuteil, 1998). Contemporary phonic instruction approaches implemented in this study also appeared to be very engaging and enjoyable to the children even after the novelty wore off. Several of the children made frequent positive statements that were reflective of their excitement and pride such as "this is fun," "I like the colored chips and letters," "I am learning how Downloaded by [UQ Library] at 18:46 12 November 2014 Comparing Phonic Approaches 168 to spell," "Watch me read these words...I can do it," "I want my mom and dad to see me do this," "Can I take my papers home to show my mom and dad?" The children ran to the door every day (even during the latter sessions) as the instructor came to their classrooms. Due to the fact that significant differences were found even with a small sample, this study is deserving of replication with larger samples so that conclusions can be generalized to a population of first-grade children. Future studies are needed to include comparisons to other contemporary phonic instruction approaches or a combination of approaches (e.g., combining word boxes with word sorts) as well as other forms of traditional instruction. Phonograms comprised the type of words taught in this study. It would be interesting to examine children's use of word boxes and word sorts with other types of high frequency words. In the current study, dependent measures only involved identifying and spelling words in isolation. Studies are needed to determine if these approaches help children transfer reading words out of context to reading words in context or perhaps how these approaches could be embedded effectively within meaning-based literacy activities. It would also be interesting to determine which approach may be more advantageous for learners with special needs and how the approaches may have differential effects on a host of other reading and writing skills. IMPLICATIONS FOR CLASSROOM USE A combination of word boxes and word sort activities can be incorporated within a comprehensive literacy program in the classroom. These approaches can be implemented for common as well as different purposes. For instance, word boxes appear to especially provide children with a supportive structure for segmenting phonemes and making left-to-right letter-sound correspondences. Word sorts appear to be helpful in comparing and contrasting spelling patterns among words. Word boxes and word sort activities appear to provide children with opportunities to study the phonological and orthographic features about words. Both approaches can be used to reinforce reading and writing connected text. Words contained in children's storybooks or in their written journals can be studied more carefully by implementing a combination of word box and word sort activities. Teachers should use a variety of phonic approaches systematically to facilitate children's knowledge about distinguishable but interconnected word study components. Flexible use of several phonic approaches may more likely meet specific needs of diverse learners. REFERENCES Adams, M. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Ball, E. W., & Blachman, B.A. (1991). Does phoneme awareness training in kindergarten make a difference in early word recognition and spelling? Reading Research Quarterly, 26,49-66. Barnes, G. W. (1989). Word sorting: The cultivation of rules for spelling in English. Reading Psychology, 10, 293-307. Bear, D. R., Invernizzi, M. A., Templeton, S., & Johnston, F. (1996). Words their way: Word study for phonics, vocabulary, and spelling. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Clay, M. (1993). Reading Recovery: A guidebook to teachers in training. Portsmouth, Downloaded by [UQ Library] at 18:46 12 November 2014 169 Reading Research and Instruction Winter 2000,39 (2) NH: Heinemann. Chali, J. S. (1996) Learning to read: The great debate. New York: McGraw-Hill. Elkonin, D. B. (1973). U. S. S. R. in J. Downing (Ed.), Comparative reading (pp. 551-579). New York: Macmillan. Groff, P. (1998). Where's the phonics? Making a case for its direct and systematic instruction. The Reading Teacher, 52,138-141. Griffith, P. L., & Olson, M. W. (1992). Phonemic awareness helps beginning readers break the code. The Reading Teacher, 45, 516-523. Hall, D. P., Cunningham, P. M., & Cunningham, J. W. (1995). Multilevel spelling instruction in third grade classrooms. In K. A. Hinchman, D. L. Leu, & C.Kinzer (Eds.), Perspectives on literacy research and practice (pp. 384-389). Chicago: National Reading Conference. Hohn, W. E., & Ehri, L. C. (1983). Do alphabet letters help prereaders acquire phonemic segmentation skill? Journal of Educational Psychology, 75, 752-762. Joseph, L. (1998). Word boxes help children with learning disabilities identify and spell words. The Reading Teacher, 42, 348-356. Morris, D. (1982). "Word sort": A categorization strategy for improving word recognition ability. Reading Psychology, 3, 247-259. Morris, D., Shaw, B., Perney, J. (1990). Helping low readers in grades 2 and 3: An afterschool volunteer tutoring program. The Elementary School Journal, 91, (2), 133-150. Robertson, C. & Salter, W. (1997). The phonological awareness test. EL: LinguiSystems. Santa, C. M. & Hoien, T. (1999). An assessment of Early Steps: A program for early intervention of reading problems. Reading Research Quarterly, 34, (1), 54-79. Stahl, S. A., Duffy-Hester, A. M., & Stahl, K. A. (1998). Everything you wanted to know about phonics (but were afraid to ask). Reading Research Quarterly, 33, 338-355. Weber, W. R., & Henderson, E. H. (1989). A computer-based program of word study: Effects on reading and spelling. Reading Psychology, 10, 157-162. Williams, J. P. (1991). The meaning of a phonics base for reading instruction. In W. Ellis (Ed.), All language and creation of literacy (pp. 9-19). Baltimore: Orton Dyslexia Society. Woodcock, R., Johnson, M. B. (1989). Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Achievement-Revised. TX: DLM Teaching Resources Yopp, H. K. (1995). A test for assessing phonemic awareness in young children. The Reading Teacher, 49, 20-29. Zuteil, J. (1998). Word sorting: A developmental spelling approach to word study for delayed readers. Reading and Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Difficulties, 14, 219-238. Zuteil, J. & Compton, C. (1993, April). Learning to spell in the elementary grades: Developing the knowledge base for effective teaching. Paper presented at the International Reading Association, Las Vegas, NV. Received: March 5,1999 Revision Received: May 26,1999 Accepted: June 4,1999