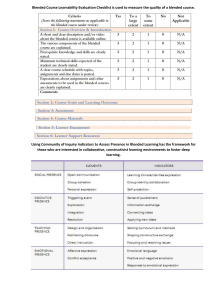

Progress in Adult Learning: Blended Experiential Methodology Master’s Thesis This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the study program of Master of Business Administration in International Management ESB Business School Reutlingen University Prepared by: Eldar Husanovic (766988) 1st Supervisor: Prof. dr. Stephan Seiter – ESB Business School 2nd Supervisor: Dr. John Wargin Strasbourg, 30.12.2020 Acknowledgments The last year and a half has been exciting, fun, and challenging. It has been a unique experience during which I learned a great deal. The writing of the thesis was the final touch to the entire journey. I have enjoyed it greatly, from meeting new people and making great friendships to insightful and valuable learning. During the process, there have been many who have helped me along the way. I would like to thank all of them sincerely for all their support. I would especially like to thank Prof. Dr. Stefan Seiter, my thesis supervisor, my mentor, for his continued insightful guidance and support. I would like to thank Dr. John Wargin for inspiring me to further explore the field I am most passionate about. I must also thank my good friend Katarina Ristic for her selfless support, time, and patience in all the fun, challenging, and inspiring discussions. Last but not least, I would like to thank my dear family, my wife Bojana, and my two beautiful children Damjan and Asja, for the continued love, understanding, and support during, not only the writing of the thesis, but throughout our entire adventure. Thank you and I greatly appreciate it. Eldar Husanovic “Tell me and I will forget, show me and I may remember; involve me and I will understand.” – Confucius ii Summary The current transformation to a digital- and knowledge-based economy makes the flexible and lifelong-learning-motivated adult workforce essential. At the same time, the gap between the industry needs and the availability of a skilled workforce is on the rise. This study sets to explore how current blended learning programs are addressing the challenge in order to attempt to identify current practices guided by the concept of blended learning as an educational model for the experiential adult learner. This study examines three themes: adult learning principles, experiential learning theory, and the concept of blended learning. The theoretical research starts with the adult learning principles of Malcolm Knowles, guiding the process towards the experiential learning of David Kolb. The research includes the review and critique of the main principles of adult learning, an overview of experiential learning theory, and the analysis of experiential teaching techniques. The outcome of the research leads to the identification of four experiential teaching techniques: case studies, simulations, hands-on experiences, and collaborative work, as highly relevant to adult learners, setting the stage for the theoretical research of blended learning methodology, its models, characteristics, tools, and elements, with the purpose of establishing its suitability as the medium for the delivery of the four identified experiential adult learning techniques. The theoretical research further leads to the distinguishing of three elements of flexibility relevant to adult learners in blended learning: time and pace, place, and path. The four experiential adult teaching techniques and the three elements of flexibility in blended learning are the basis for the creation of categories of the quantitative and qualitative analysis of leading European business school blended graduate programs. In the outcome, it is evident that all the teaching techniques and elements of blended learning were identified in all fourteen programs, at varying levels and degrees, leading to the creation of key takeaways from the study as well as key concluding points. iii Table of Contents Acknowledgments ..........................................................................................................ii Summary ....................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... iv List of Abbreviations ...................................................................................................... vi List of Illustrations ........................................................................................................ vii List of Tables ................................................................................................................ viii 1 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................1 1.1 Literature Review ................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Aims and Research Question ................................................................................. 3 Adult Learning.........................................................................................................6 2.1 2.1.1 2.1.2 3 Andragogy .............................................................................................................. 6 Characteristics of Adult Learner............................................................................................. 6 Critique .................................................................................................................................. 9 Theory of Experiential Learning .............................................................................10 3.1 Definition ............................................................................................................. 10 3.2 Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory ..................................................................... 10 3.3 Kolb’s Learning Cycle ........................................................................................... 12 3.4 Benefits................................................................................................................. 13 3.5 Critique ................................................................................................................ 14 3.6 Teaching Techniques of Experiential Learning ..................................................... 14 3.6.1 3.6.2 3.6.3 3.6.4 3.7 Case Studies ......................................................................................................................... 15 Simulations and Games ....................................................................................................... 15 Collaborative Work (Group / Peer-to-Peer Learning) .......................................................... 16 Internships / On-the-Job Experiences .................................................................................. 17 Connecting Experiential Learning with Adult Learner .......................................... 17 4 Conclusion – Experiential Learning of Adults .........................................................17 5 Blended Learning ..................................................................................................19 5.1 Definition ............................................................................................................. 19 5.2 Models ................................................................................................................. 19 5.3 Face to Face Component in Blended Learning ..................................................... 21 5.3.1 5.3.2 5.4 5.4.1 5.4.2 Characteristics ..................................................................................................................... 21 Face-to-Face Activities and Tools ......................................................................................... 21 Online Component of Blended Learning .............................................................. 23 Characteristics ..................................................................................................................... 23 Online Activities and Tools .................................................................................................. 24 5.5 Blending Face-to-Face with Online ...................................................................... 26 5.6 Blended Learning as Adult Learning Concept ....................................................... 27 5.7 Flexibility .............................................................................................................. 28 iv 5.8 6 Conclusion – Blended Learning Elements of Flexibility ........................................ 28 Research Methodology..........................................................................................30 6.1 Data Collection Method ....................................................................................... 30 6.2 Data Analysis Method .......................................................................................... 30 6.2.1 6.2.2 6.2.3 6.2.4 6.2.5 7 Content Analysis .................................................................................................................. 30 Directed Content Analysis.................................................................................................... 31 Limitations of Research Design ............................................................................................ 32 Implementation Process ...................................................................................................... 32 Implementation Practicalities .............................................................................................. 32 Findings and Analysis ............................................................................................35 7.1 Frame 1: Teaching Techniques ............................................................................... 35 7.1.1 7.1.2 7.1.3 7.1.4 7.2 Category 1: Case Studies ...................................................................................................... 35 Category 2: Simulations ....................................................................................................... 36 Category 3: Hands-On Experience (workshops, on-the-job experiences, internships) ........ 37 Category 4: Collaborative Learning (peer-to-peer, group work, discussions) ...................... 40 Frame 2: Blended Learning Elements of Flexibility .................................................. 41 7.2.1 7.2.2 7.2.3 7.3 Category 1: Time and Pace................................................................................................... 41 Category 2: Place (flexibility in face-to-face, flexibility online) ............................................ 44 Category 3: Path .................................................................................................................. 45 Overall Findings and Analysis ................................................................................. 47 7.3.1 7.3.2 7.4 Frame 1 ................................................................................................................................ 47 Frame 2 ................................................................................................................................ 48 Key Takeaways ...................................................................................................... 50 8 Conclusion .............................................................................................................51 9 Limitations and Further Research ..........................................................................52 List of References ..........................................................................................................54 Appendix A Frame 1: Collected Research Data ..........................................................59 Appendix B Frame 2: Collected Research Data ..........................................................64 Appendix C List of Sources Used for Data Collection ..................................................72 Declaration of authorship of an academic paper ...........................................................74 v List of Abbreviations AACSB…………………...The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business MOOC…………………………………………………….Massive Open Online Course WHO…………………………………………………………World Health Organization vi List of Illustrations Illustration 1. The Experiential Learning Cycle .................................................................. 13 vii List of Tables Table 1. Kolb’s Model with Suggested Techniques ............................................................ 18 Table 2. Frame 1 Results ..................................................................................................... 47 Table 3. Frame 2 Results ..................................................................................................... 48 viii 1 Introduction The impact of the Internet over the last ten years intensified, leading to an accelerated change of business pace and contributing to an exponential increase in knowledge and complexity. The impact is no exception to the field of adult education, currently in the process of transformation (Benson-Armer, Gast, & Dam, 2016). The pressure for changes in delivery and “consumption” of education is high due to the fast change of technology requiring new knowledge and skills. The period between the time knowledge is acquired and the time it becomes obsolete has significantly shortened (Brassey, Christensen, & Dam, 2019). Currently, the half-life of knowledge is estimated at five years (Bersin, Schwartz, Pelster, & van der Vyver, 2017). Consequently, this has contributed to the evolution of the global workforce, making it highly dependent on new technology, new knowledge, and continuous capacity to think across disciplines, construct information, and connect complex ideas (Hans & Shawna, 2019). These developments have caused a general shift to a digital- and knowledge-based economy, making flexible and lifelonglearning-motivated workforce essential (Brassey et al, 2019). This shift can also be seen through market capitalization in major global companies, increasingly being based on intangible assets (Elsten & Hill, 2017). All of the above placed a premium on education and training, with upskilling, reskilling, and reinventing models of adult learning becoming more important than ever before (Brassey et al, 2019). In fact, it can be said that reinventing how adults continually learn, unlearn and relearn, in other words, how they transform, is a major global task to be addressed to shorten the rising gap between industry needs and the availability of skilled workforce (Hans & Shawna, 2019). Concerning learning transformation, three additional points ought to be mentioned, all three challenging current educational habits. The first is the fact that internet technology is rapidly altering individual access to knowledge. For example, significant activities have already been undertaken to provide knowledge fully online from credible sources, e.g. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC) by Stanford, MIT, Harvard, Coursera, and so forth, enabling global access to wide audiences. The second point is related to the industry’s increasing concerns related to the inadequate preparedness of new employees (Shepherd et al, 2019). This concern is directly connected with the ability of graduates to apply acquired university knowledge to work. Consequently, the industry is pressing for changes expecting graduates capable of transferring acquired knowledge skills, and attitudes into action, especially having in mind that work environments are under continual competitive and disruptive challenges. The third point is that learners themselves already have significantly changed expectations what education is to offer them. Namely, the learner guides himself/herself towards activities that are experiential, interactive, and insightful, unlike the current focus on learning how and what to memorize (Hase & Kenyon, 2001). 1.1 Literature Review Experiential learning that follows adult learning principles implemented with blended learning methodology as the educational model is seen by a significant number of institutions and researchers as a direct response to the aforementioned questions and challenges. Unlike fully online learning or face-to-face-only approach, the concept of blended learning, defined in broad terms as a combination of some form of face-toface and online learning experience, has the potential to offer a large array of opportunities in combining the advantages of both modes of instruction thus providing learners with the flexibility “to operate successfully in, and across, different contexts, utilizing their everyday life-worlds as learning spaces” (Cook, Pachler, and Bachmair, 2011, as cited in Bocconi & Trentin, 2014, p. 517). Similarly, according to the Digital Action Plan 2021-2027 of the European Commission, the future leadership and capacity are connected not only to implementing different tools in digital education but also ensuring “effective hybrid solutions between online and onsite delivery” (European Commission, 2020, p. 80). According to the survey for the Digital Action Plan, the highest-ranked disadvantage of digital education is the lack of face-to-face communication and interaction, which can be addressed by one of the major advantages of blended learning, indicated in the survey, which is the presence of some form of face-to-face activity (European Commission, 2020). Similarly, the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a systematic literature review in 2019 with the ultimate objective of creating and implementing its own strategy for lifelong learning to be applied globally. The literature review included leading studies of lifelong learning, encompassing contemporary policies, practices, and research while focusing on hybrid, online, onsite, simulated, and mobile learning environments. The direct aim of the literature review was to establish current best practices in lifelong adult and digital learning. It covered 94 highly relevant studies 2 published from 2000 to the present, with one of the key conclusions being that formal learning should include a variety of different methods. A recurrent theme throughout the literature was that programs should be learner-centered and blend a variety of approaches, recommending a blend of in-person and distance learning, with blended learning being a preferred method of delivery compared to either online-only or in-person only (World Health Organization, 2019a). Further, in a large survey conducted by McKinsey in 2016, 1,500 executives, 120 learning and development leaders, and 15 Chief Learning Officers were interviewed from 91 organizations. The research concluded that a large number of employees will need to learn new skills to remain employable and that as many as 800 million jobs will be displaced by 2030. The research confirmed that adult learning has to undergo revolutionary changes to keep pace while focusing on blended-learning solutions that combine digital learning, fieldwork, and highly immersive classroom sessions (Brassey et al, 2019). Furthermore, according to the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) Collective Vision for Business Education, it is technology platforms that will have the task of enhancing complementary learning experiences and opportunities enabling more customized programs to learner's actual role, industry, or career path, by leveraging experiential learning. Similarly, the four deans of leading business schools, Harvard, Wharton, Columbia, and Stanford, agreed that the future of business education will focus on: • Application and interaction of acquired knowledge while lecture-like content will be provided online • Experiential learning applied outside of the classroom in local and global contexts • Balancing learning-by-studying with learning-by-doing (Garrett, Saloner, Nohria, & Hubbard, 2016) 1.2 Aims and Research Question Higher education institutions have the purpose and obligation to persistently meet student needs, requirements, and expectations by providing high-quality, relevant, and accessible education. It is also relevant that educational institutions meet the needs of employers by educating students capable of applying the acquired knowledge in real-world situations of 3 an ever more dynamic and complex society (Demirer & Sahin, 2013). To move in this direction, it may be relevant to make awareness of the contemporary value-creating learning formats available. With blended learning becoming a prioritized strategic development, it seems sensible to look more deeply into current practices that could assist educational institutions in the creation, deployment, and delivery of blended educational programs. Although there is a significant number of studies investigating either blended learning or experiential learning of adults, there are not many studies focusing on blended learning as an educational model and a facilitation platform for the delivery of educational programs based on adult learning principles and experiential learning theory. The forming of the research questions was deduced from theory. The theoretical research first included the examination of adult learning principles, focusing on Malcolm Knowles, guiding the research towards the experiential learning of David Kolb. The research included the review and critique of main principles of adult learning, overview of experiential learning theory, as well as examination of experiential teaching tools, elements, and techniques that are in line with adult learning principles of Malcolm Knowles. The outcome of the research led to the establishing of four experiential teaching techniques: case studies, simulations, hands-on experiences, and collaborative work, as highly relevant to adult learners. From this framework stems the first research question: Research question 1: Do existing blended learning programs implement the four teaching techniques of experiential adult learning, as deduced from theories? Once the experiential teaching techniques became established, the research of blended learning methodology models, elements, and tools led to the identification of flexibility as a key benefit of blended learning, particularly relevant to adult learners. This led to the distinguishing of three elements of flexibility in blended learning: time and pace, place, and path. Therefrom stemmed the second research question: 4 Research question 2: Do existing blended learning programs implement the three elements of flexibility in blended learning, as deduced from theories? With the aforementioned in mind, this study sets to explore existing blended learning programs from the perspectives deduced from theories, in order to attempt to understand and establish the current practices based on the analysis of teaching techniques and elements of leading higher education graduate blended programs. The study extends the literature by exploring how digital- and knowledge-based economy impacts current blended learning practices of highly ranked business graduate programs from the perspective of an experiential adult learner. 5 2 Adult Learning 2.1 Andragogy According to Knowles (1980), “andragogy is a set of principles applicable to most adult learning situations” (as cited in McLean, 2017, p. 596) and attributed to helping educators better understand adult learning (Knowles & Swanson, 2005). It is considered the most influential concept in contemporary adult education (Cooke, 1994) and a framework for learning practice (Youde, 2018). According to Jarvis (2012), Kember (2007), and Savicevic (2008), the Knowles notion of Andragogy is among the most referenced notions in terms of adult learning (as cited in Youde, 2018). Also, while elaborating on the level of acceptance and application of andragogy globally, Pratt (1993) elaborates “it (andragogy) will continue to be the window through which adult educators take their first look in the world of instructing adults” offering “familiar and recognizable ground from which to conduct adult education” (as cited in Cooke, 1994, p. 73). 2.1.1 Characteristics of Adult Learner According to Knowles and Swanson (2005), six key assumptions are essential to teaching and understanding the adult learner. The following six assumptions are considered the principles of andragogy: need to know, self-directedness, prior experience, readiness, relevancy, and internal motivation. 1. Need to Know It is essential for adults to understand why learning is taking place and how the learner contributes to it, directly or indirectly. Further elaborating on this principle, Knowles and Swanson (2005) explain that adults generally invest a great deal of energy to understand the benefits of learning. Therefore, it is of the essence for the adult learner to first establish their "need to know", “in which the learners discover for themselves the gap between where they are now and where they want to be” (Knowles & Swanson, 2005, p. 65). To facilitate it, Knowles & Swanson suggest the use of diagnostic tools by teachers (learning facilitators) to assist the learner better understand their current level of knowledge in comparison to knowledge expected to be acquired. Since the main element of the discrepancy assessment is the learner’s own perception, the assessment is essentially a selfassessment, in which the learning facilitator provides learners with procedures and tools needed to acquire information enabling the learner to understand their level of competencies. The best tools to be used are experiential (e.g. simulations), which enable 6 learners to easily realize by themselves what their knowledge gap is. “At the very least, facilitators can make an intellectual case for the value of the learning in improving the effectiveness of the learners’ performance or the quality of their lives” (Knowles & Swanson, 2005, p. 64). 2. Self-Directedness Knowles et al. (2015) explained the self-concept as one in which adult learner is held responsible for their own decisions leading to the concept of self-direction. According to Knowles & Swanson (2005), “once they have arrived at that self-concept, they develop a deep psychological need to be seen by others and treated by others as being capable of selfdirection” (p. 65). Typically, it is about respecting the knowledge of the adult learner as well as their learning aspirations, while maintaining the concept of accountability for the decisions they make on their behalf. According to this principle, learning imposed on adults can lead to resentment creating unwanted tensions which may lead them to a dependency approach, experienced while in school as children. Consequently, educators have a duty to assist adult learners in the transition from being directed to self-direction (Youde, 2018). Similarly, as explained by Knowles, “people tend to feel committed to a decision or activity in direct proportion to their participation in or influence on its planning and decision making”. The reverse is even more relevant as adult learners “tend to feel uncommitted to any decision or activity that they feel is being imposed on them without their having a chance to influence it” (Knowles & Swanson, 2005, p. 123). It is important to mention that the traditional educational system does not nurture this approach. To facilitate it, it is important to undertake steps that prepare the learner better understand the concepts of proactivity, identifying knowledge the learner already possesses, as well as forming collaborative relationships (Knowles & Swanson, 2005). 3. Prior Experience When it comes to this principle, Knowles and Swanson (2005) explain that adult learners, as opposed to young learners, enter the learning process with a great deal of knowledge, skills, and competencies. Namely, the principle is closely related to life experiences adult learners bring with them, representing a valuable asset that assists the learning process in a number of experiential activities. Consequently, in relation to this principle, Knowles and Swanson claim that “the emphasis in adult education is on experiential techniques— techniques that tap into the experience of the learners, such as group discussions, 7 simulation exercises, problem-solving activities, case methods, and laboratory methods instead of transmittal techniques”. Also, greater emphasis is placed on “peer-helping activities” (Knowles & Swanson, 2005, p. 66). Still, previous experiences can also inhibit new learning. Old models of thinking may hinder it. Consequently, the lecturer's role, in this case, is important as there is a need to motivate unlearning and reassure learning of new (Youde, 2018). 4. Readiness According to Knowles and Swanson (2005), adults acquire “new knowledge, understandings, skills, values, and attitudes most effectively when they are presented in the context of application to real-life situations” (p. 67). For the educator, this means that understanding the adult learner's background and the readiness for learning is important. According to this principle, learning to adults is more relevant when there is direct applicability to work. This principle is frequently related to a stage in life that is often developmental, for example when an adult is moving from one stage of their life to another. This further implies that the lecturers, when preparing, should keep in mind that learning content should be as relevant as possible to the application in real life (Youde, 2018). According to Knowles and Swanson (2005), adults are life-focused in their orientation towards learning. Adult learning is problem-oriented, attempting to acquire the knowledge needed to address a specific problem. Therefore, it is important that the adult learner realizes that knowledge acquired will enhance his/her ability to perform or be able to deal with certain life situations in an improved manner. Consequently, such learning provides the adult learner with a purpose that leads to truly personalized learning. 5. Internal Motivation Adults are intrinsically motivated. As stated above for the other principles, adults' motivation is based on problems that are personally considered as important by the learner. Thus, communicating the learner's needs with the learning facilitator to better understand the requirements of the learner may contribute to the improvement of knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Knowles & Swanson, 2005). 8 2.1.2 Critique Merriam (2001) claims that Knowles' all-encompassing assumption of all adults being selfdirected is questionable, stating that "some adults are highly dependent on a teacher for structure, while some children are independent, self-directed learners", emphasizing that it should be looked at on a rather individual basis (p. 5). McLean (2017) also questions the generalization of learning abilities and motivations to learn. (2017). Furthermore, Merriam (2001) states that although andragogy supports abilities and readiness to undertake an initiative, variations among adult learners do not seem to be included, especially concerning learners' social and cultural background. Grace (1996) and Jarvis (2012) similarly criticize andragogy as being limiting due to the absence of sociological perspective as well as being isolating due to non-consideration of social structure (as cited in Youde 2018). Another, frequently disputed and discussed principle is the andragogical model’s principle “motivation to learn”, which proposes that adults, unlike children, respond better to intrinsic rather than extrinsic motivators. It is being disputed by stating that children may respond sometimes better to intrinsic motivators while adults can better in some cases respond to extrinsic motivators (Youde, 2018). According to Swain & Hammond (2011), both motivators have indicated a positive impact on the achievement of adult learners in contexts of higher education. Also, Feinstein et al (2007) claim that in cases when adult learners' motivation is only instrumental, e.g. undergoing a higher education program to acquire work promotion, it would be expected that education would also need to incorporate external motivators as well into their courses (as cited in Youde, 2018). Having in mind the sound critique of adultst being only internally motivated, as proposed by Malcolm Knowles, and due to the limited sources and resources for this study, I have decided to leave out internal motivation as an adult-learning principle in the rest of the thesis. 9 3 Theory of Experiential Learning 3.1 Definition Experiential learning was first defined in 1969 by Rogers (2016) as the "quality of personal involvement, the whole-person in both his feeling and cognitive aspects being in the learning event" (as cited in Kurthakoti & Good, 2019). Hoover (1974) provided an extended definition by elaborating that experiential learning exists when “a personally responsible participant(s) cognitively, emotionally, and behaviorally process(es) knowledge, skills and/or attitudes in a learning situation characterized by a high level of active involvement” (p. 35). Most known definition of experiential learning in management education is the one by Kolb (1984) who defined it as "a holistic integrative perspective on learning that combines experience, cognition, and behavior". Lewis and Williams (1994) defined it in a simple form stating that experiential learning is the same as learning by doing or learning from experience. 3.2 Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory David Kolb’s model of experiential learning is considered as most recognized, even though many had been proposed before him (Ahn, 2008). In fact, it is considered as one of the most influential theories on how managers acquire knowledge using an experiential methodology (Li et al., 2013). According to Kolb and Kolb (2005), experiential learning is a multilinear model that is based on processes and focused on adult development (2005). The theory is built on six propositions as indicated below: Learning is best conceived as a process, not in terms of outcomes. To improve learning in higher education, the primary focus should be on engaging students in a process that best enhances their learning—a process that includes feedback on the effectiveness of their learning efforts. As Dewey notes, “[E]ducation must be conceived as a continuing reconstruction of experience: . . . the process and goal of education are one and the same thing” (Dewey 1897: 79). All learning is relearning. Learning is best facilitated by a process that draws out the students’ beliefs and ideas about a topic so that they can be examined, tested, and integrated with new, more refined ideas. 10 Learning requires the resolution of conflicts between dialectically opposed modes of adaptation to the world. Conflict, differences, and disagreement are what drive the learning process. In the process of learning, one is called upon to move back and forth between opposing modes of reflection and action and feeling and thinking. Learning is a holistic process of adaptation to the world. Not just the result of cognition, learning involves the integrated functioning of the total person, thinking, feeling, perceiving, and behaving. Learning results from synergetic transactions between the person and the environment. In Piaget’s terms, learning occurs through equilibration of the dialectic processes of assimilating new experiences. Knowledge is created through learning. Experiential learning builds upon a constructivist theory of learning. This means that social knowledge is created and re-created in the learner through a transformation of experience, as opposed to the "transmission" view where pre-existing and fixed ideas are transferred to the learner (Kolb & Kolb, 2005, p. 194). David Kolb created his experiential learning theory on some of the leading scholars of the 20th century, including John Dewey, Carl Jung, William James, Jean Piaget, and others, who placed experiential learning in focus when it comes to adult learning and development (Kolb, 2005). The experiential theory is based on three key models that Kolb uses to describe the process. The first is the Lewinian Model, seen as the main model of the experiential theory. It contains four stages. The first stage is the actual experience (i.e., field trip, practical workshop), the second stage is the reflection on the first stage, the third stage is when the learner attempts to conceptualize the experience while the fourth stage is when the learner contemplates about the application and testing of the new model for future experiences (Healey and Jenkins, 2000). 11 The second model is John Dewey’s model of learning, similar to Lewin’s but focuses more on how learning transfers concrete experiences through impulses, feelings, and desire for learning higher order of purposeful action (Kolb, 1984). The third model that Kolb uses is Piaget’s learning and cognitive development model. This model focuses on the impact of experience concepts on the real world and the acceptance of experiences and events into existing concepts. According to Piaget, a balanced approach of both leads to adequate adaptation. When one dominates over the other, the outcome is either the imitation of environmental contours or in the opposite case imposing one's concept regardless of environmental realities (Kolb, 1984). All three of the aforementioned scholars, Dewey, Piaget, and Lewin, stress that transactions between the environment and the person are the key to the active creation of the knowledge process (World Health Organization, 2019). 3.3 Kolb’s Learning Cycle David Kolb’s experiential learning theory is represented through the Kolb's Learning Cycle defining experiential learning as a "process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience" (Kolb, 1984, p.38). The Learning Cycle is divided into two modes of comprehending experience named Concrete Experience (CE) and Abstract Conceptualization (AC) and two modes of transforming experience, named Reflective Observation (RO) and Active Experimentation (AE). The two modes are divided into four stages as follows: - Concrete Experience (CE) - the first stage represents the concrete experience of undergoing a certain situation. - Reflective Observation (RO) - the second stage is seen as a process of reflective observation where the learner is trying to make sense or reflect upon what has happened through description, interpretation, and understanding of the relationships of events. 12 - Abstract Conceptualization (AC) - the third stage is the creation of abstract concepts in which learned theories and knowledge are added to the self-reflective analysis of the experience to complement and facilitate the learning process. In this stage, the knowledge and theories may come from different sources including studies, ideas from colleagues, new observations, and so forth. - Active Experimentation (AE) - the fourth stage is the active experimentation in which the learner tests new ways of thinking, leading to new experiences that initiate the new cycle of learning (Kolb, 1984). Ideally, the learner goes through all phases, experiencing, reflecting, thinking, and acting, in response to the situation being learned. Observations and reflections in the process are based on the actual immediate experiences (Kolb, 2015). Illustration 1. The Experiential Learning Cycle (Passarelli & Kolb, 2011, p.5) 3.4 Benefits A significant number of researchers claim that experiential learning methods provide a significant number of advantages and benefits that lead to improved student confidence and motivation, augmented concept development, boosted memory, increased understanding of constructed knowledge and concept development, and achieving deep learning (Callister & Love, 2016). Furthermore, students who employ experiential 13 methods, such as the teaching of others or learning from hands-on experiences, have resulted in significantly higher learning scores when compared to traditional methodologies of learning, such as direct lecturing, use of audio-visuals, reading, and so forth. Additionally, students who study at educational institutions that have a strong experiential focus are in an advantageous position due to their practice of real-life relevant problem-solving as well as engaging experiential hands-on activities where they can apply and test theoretical knowledge (World Health Organization, 2019a). Evidence also points to the fact that hands-on experiences are a crucial aspect of delivering skills‐based training (Callister & Love, 2016). 3.5 Critique Despite its strong influence on the experiential theory's principles and general omnipresence, there is a number of scientists providing various criticism and opposing experiential learning theory (Russel, 2006). The main point being questioned is its narrow psychological concept of learning (Seaman, 2007), which neglects that learners’ perceptions and actions are also culturally predisposed (Miettinen, 2000), putting learning into a separate isolated experience space (Seaman, 2007). According to Miettinen (2000), the concept of experiential learning has an ideological function, where reliance is in the faith of the innate individual’s ability to learn and grow. Other criticisms discuss the absence of feeling as neither being defined nor elaborated in the experiential learning theory. Miettinen (2000) further elaborates that Kolb ignores experience as an essential segment of experiential learning. This could be seen in Kolb's statement that "…learning, change, and growth are seen to be facilitated by an integrated process that begins with here-and-now experience followed by the collection of data and observations about that experience." (Kolb, 1984, p. 21), stressing the fact that experience is only happening at the moment of the actual experience altogether ignoring previous experience contributed to the process of learning. However, Kolb does mention in the second principle of the Experiential Theory that all learning is relearning, which contradicts the previous statement while confirming that previous experience plays an important role. 3.6 Teaching Techniques of Experiential Learning Experiential activities are divided into two groups, classroom experiential activities and field-based activities (Nagar & Hurd, 2019). Field-based activities include hands-on learning processes such as in-company projects, internships, workshops, and so forth. On 14 the other hand, experiential learning based on experiential classroom face-to-face activities is presented in a multitude of approaches, most important of which being case studies, simulations, and games, role-playing, critical incidents, presentations, as well as different types of group-engaging activities. Real-life scenarios can also be used in experiential classrooms or laboratories (Lewis & Williams, 1994). Inside the experiential classroom, the lecturer is not doing frontal lecturing but rather facilitating and directing students, inciting them by relevant questions, to guide them to the achievement of learning objectives (Nagar & Gurd, 2019). A number of approaches are available to educators when delivering learning based on experiential learning theory (Kurthakoti & Good, 2019). According to Knowles (2005), the emphasis of adult education should be on experiential learning techniques that directly stimulate learners’ experience encompassing group work, simulations, problem-solving case studies, and hands-on peer helping activities. Considering that the techniques recommended by Knowles, are in line with the previously stated experiential learning techniques, for the purpose of this study I narrow them down and group to case studies, simulations and games, collaborative work and internships/on-the-job experiences. 3.6.1 Case Studies The case study method, in terms of experiential learning in business education, can be defined as “a method that involves studying actual business situations, written as an indepth presentation of a company, its market, and its strategic decisions to improve a manager's or student's problem-solving ability” (Kurthakoti & Good, 2019). This method provides students with an opportunity to be put in a scenario in which they are being given a real or similar to the real case with challenges to be addressed, enabling them to apply acquired theoretical concepts into real-life scenarios (Kurthakoti and Good, 2019). 3.6.2 Simulations and Games According to Shepherd et al (2019), simulations can be perceived as an experiential learning method, strategic and dynamic in nature, effectively transforming theoretical concepts into practice by using different modes of learning that employ life-like experiences in different kinds of learning spaces. It attempts to replicate real-life work environments by providing learners with contextualized themes, techniques, technologies, and methods in a controlled environment. It directly supports the learning of technical and 15 non-technical skills with the ultimate objective of preparing and equipping learners with knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed once employed (Shepherd et al, 2019). According to Faria et al., (2008), the main reason why simulations and games in the last ten years have been used in business schools was to enable students to acquire experience and assist them in forming strategies, improve their decision-making skills and facilitate teamwork. Similarly, Kurthakoti and Good (2019), state that it has been established that simulations and games improved the learning of students in a number of segments. Namely, it improves the higher order of cognitive processes, application, analyzing, evaluation, and creation of concepts. 3.6.3 Collaborative Work (Group / Peer-to-Peer Learning) According to Gaumer, Cotleur, and Arnone (2012), group work has a number of significant advantages. These include the generally accepted rule of thumb that people who work in groups achieve more than people working individually, can gather and analyze a larger amount of data, improve relationships, improve the ability to better deal with conflict, better organize tasks to reach set goals, exercise leadership roles as in real-life scenarios and so forth (as cited in Kurthakoti and Good, 2019). Also, collaborative learning, as the main characteristic of group projects, results in enhanced learner satisfaction. It also contributes to the improvement of the social part of learning among the students in a distance learning education. The group project method is even more important in understanding teamwork as the basis of future work-life and due to the high level of skill transferability, when compared to other methods. It provides an experiential context in which learners can use problem-solving scenarios to learn and apply their knowledge (Kurthakoti and Good, 2019). Furthermore, according to the World Health Organization (2019), models of group experiential learning improve specific skills as well as knowledge in general, while minimizing mistakes and expanding practical aspects of learning. It is important to mention that group and peer-to-peer learning are considered crucial components of experience-based learning (Nagar and Hurd, 2019). On the other hand, there are certain shortcomings to group work, and these can be seen through group grading that some may find unfair due to different potential investment into group work, freeriding, team compositions, and sometimes difficulties in agreeing on work schedules. 16 3.6.4 Internships / On-the-Job Experiences Internships and in-company projects are a widely used experiential learning approach in many business school graduate-level programs. According to AACSB, students are expected to have an opportunity during the program to apply business-related knowledge and skills. According to Kurthakoti and Good (2019), internships contribute to deep learning which leads to significant other types of benefits such as higher academic achievement, development of networking skills, increased ability to find long-term employment, enhanced understanding of theoretical concepts, improved problem solving due to the ability to connect theory with practice, cultural awareness, improved communication, and social skills, and so forth. 3.7 Connecting Experiential Learning with Adult Learner Considering the relevancy of the compatibility of andragogy with experiential learning theory in positioning this thesis, it is important to review Knowles’ perception of Kolb’s Learning Cycle. According to Knowles (2005), Kolb with his experiential learning theory contributes significantly to the literature of experiential learning, most importantly by providing it with a practical learning approach in experiential practice as well as the theoretical basis for the research in experiential learning. Furthermore, Knowles emphasizes that the experiential learning theory and its accompanying learning cycle are a highly valuable framework when it comes to the creation of adult learning experiences, which can be applied on both, macro and micro levels. Namely, all four stages of the learning cycle can be applied to the overall educational program and class level, while being able to be applied to individual teaching units as well. Furthermore, Knowles (2005) explains that an important benefit of experiential learning to adults is improved performance upon the completion of education, which would also be beneficial in many other domains of adult learning. He concludes that the “experiential approach to learning has become firmly rooted in adult learning practice” (Knowles, 2005, p. 197). 4 Conclusion – Experiential Learning of Adults According to Malcolm Knowles (2005), the role of experiences is of great relevance to adult learners. Knowles explains it by stating that “for many kinds of learning, the richest resources for learning reside in the adult learners themselves” emphasizing that adults seem to “learn best when new information is present in real-life context”. He adds that it contributes to the shaping of adult learners and concludes that “the emphasis in adult 17 education is on experiential techniques, techniques that tap into the experience of the learners, such as group discussions, simulation exercises, problem-solving activities, case methods, and laboratory methods instead of transmittal techniques”, with emphasis on “peer-helping activities”. As the outcome, Knowles suggested the most favorable teaching techniques for adults in experiential learning following Kolb’s Learning Model: Kolb’s Stage Example Learning/Technique Concrete Experience Simulation, Case Study, Field Trip, Real Experience, Demonstrations Reflective Observation Discussion, Groups, Designated Observers Abstract Conceptualization Sharing Content Active Experimentation Laboratory Experiences, On-the-Job Experience, Internships, Practice Sessions Table 1. Kolb’s Model with Suggested Techniques (Knowles & Swanson, 2005) Determining key teaching techniques in the experiential learning of adults is a necessary segment to address the first research question. Guided by the aforementioned list of teaching techniques, as suggested by Malcolm Knowles, I grouped the aforementioned techniques into four categories of key teaching techniques as follows: 1. Case studies 2. Simulations 3. Collaborative work (peer-to-peer learning, group work, discussions, debates) 4. Hands-on experience (laboratory/workshop experiences, on-the-job experience, internships, hands-on practice sessions) These four categories encompass all the teaching strategies as proposed by Malcolm Knowles and will be used to address the first research question. The objective of grouping was to set criteria for further research process. Namely, these four groups of techniques will represent the four categories of the first frame of the research, which is to identify and analyze their presence in the selected blended learning graduate programs. 18 5 Blended Learning 5.1 Definition Although it is clear that blended learning represents some sort of combination of face-toface and online learning, there does not seem to be a consensus on a widely accepted definition. Garrison and Kanuka (2004) and Vaughan (2013) define blended learning as a learner-centered, multi-modal, flexible, and self-paced approach that emphasizes the fact that simply adding some online aspects to the face-to-face mode should not be considered blended learning. Picciano (2009) implies that blended learning is represented through a reduced amount of face-to-face learning by using a certain level of online activity, while Boelens et al (2017) see blended learning as a deliberate blending of online and onsite activities to support and stimulate learning. Maarop and Embi (2016) cite Littlejohn and Pegler who see blended learning as the concept of 'strong' and 'weak' blends of small to a significant amount of online activities being part of blended learning programs. This is only a portion of a vast number of definitions of blended learning that can be found in the literature. The non-existence of a universally recognized definition is obvious. For clarity, in this thesis, blended learning is defined as an “approach mixing face-to-face and online learning, with some element of learner control over time, place, path, and pace” (European Commision, 2020). 5.2 Models Although there seem not to exist universally accepted frameworks guiding blended learning, or specific principles of blended learning instructional design, (Graham et al, 2014), there does seem to be a consensus on offered models. These models indicate a multifaceted learning environment of blended methods. The reason is the very concept of blending, that is, combining varied learning approaches in a number of different ways when creating and designing learning activities (Yang, 2016). It was Horn and Staker (2014) who introduced the most known and most used categorization of blended learning models. All of the models incorporate some form of formal educational approach, combined with some kind of part-time content delivery using face-to-face and online environments. However, each of the models has been created in order to deliver successful teaching under different circumstances. The models of blended learning are as follows: 19 1. Rotational Model encompasses several different teaching approaches that have been categorized into four sub-categories: - individual rotation is represented through a personalized list of activities through stations based on the individual needs of a learner - station rotation distributes experiences of a learner through all learning stations equally - lab rotation provides physical rotation of space, i.e. moving from a computer lab to a workshop facility (Graham et al, 2014) - flipped classroom (known also as an inverted classroom) provides the learning environment where face-to-face onsite lecturing is substituted by online lectures, enabling the use of an onsite component of blended learning for more interactive or practical experiences (Yang, 2016). The onsite segment is utilized for exercises, peer-to-peer work, discussions, application of theory to work, or laboratory/workshop environment, thus contributing to the higher-order of learning. In this model, therefore, the teaching approach has been reversed (Serrano et al, 2019). 2. Flex Model can be described as a teaching model in which the curriculum is delivered mostly online through the digital platform, however, with a possibility to customize the learning pathway by providing face-to-face onsite support when needed (Bryan & Volchenkova, 2016). This model provides learners with the ability to have a flexible schedule adjusted to the learning needs. Teachers are available to students for face-toface onsite consultations on an adjustable basis (Douglas et al, 2019). 3. A La Carte Model (known also as Self-Blend Model) is a model in which learners mostly study onsite, however, a certain, lower percentage of activities, can be parallelly deployed using the online digital platform, thus complementing traditional learning (Yang, 2016). This could be perceived as a good model for educational institutions that do not have a strong offer of elective courses and would like to provide more options for their students (Douglas et al, 2019). 4. The Enriched Virtual Model represents an approach in which most of the learning takes place online via a digital platform (Graham et al, 2014), with some intermittent visits of 20 students to brick and mortar locations (Bryan & Volchenkova, 2016). This enables students to conduct most of their studies by following their own pace from the location of their choosing, usually not requiring daily school attendance (Douglas et al, 2019). 5.3 Face to Face Component in Blended Learning 5.3.1 Characteristics According to Green (2015), face-to-face activities in blended learning are perceived as enablers of highly collaborative space by inciting active learner participation in the learning process, in which the teacher acts as a learning facilitator, rather than content provider. Fleck (2012) similarly states that face-to-face learning activities in blended environments shall be created in a manner that enables learners' creation of their meaning of knowledge contrary to the direct transmission of knowledge by the teacher. Green (2015) further emphasizes that face-to-face activities in blended learning deter individual work and stimulate peer-to-peer and peer-to-lecturer interactions through engaging activities, such as discussion, debate, cooperation, and collaboration (Kjaergaard, 2017). Asef-Vaziri (2015) confirms that the time gained by freeing the direct lecturing time for other activities provides the learner with more possibilities for in-depth discussions. According to Green (2015), the onsite aspects of blended learning seem to be in line with andragogical principles of adult learning as well as experiential learning by allowing learners to “construct their own understanding and educational meaning” (p. 183). Green (2015) also claims that engaging in face-to-face activities stimulates learners with interactions that foster experiential learning. The face-to-face component of blended learning is also important in establishing social relations among learners as well as establishing networks, as a useful way in which their interactions can continue outside the class and be beneficial in different ways (Kjaergaard, 2017). 5.3.2 Face-to-Face Activities and Tools The onsite aspect of blended learning is closely related to active learning. It is enabled by turning onsite activities from the traditional frontal lecturing format to the one that fosters interactive learning (Vaughan, 2007, p. 83). It is implemented through the use of a number 21 of techniques, as indicated below, that are in line with the experiential techniques based on the adult learning principles, as discussed in the previous chapters. Case Studies Asef-Vaziri claims that "freeing up class time also enables the instructor to discuss more real-world applications and close to real-world case studies" (2015, p. 79), which follows the suggested practices for experiential learning of adults. In line with that, Fleck states that different tools and activities are used to focus on more engagement by the learner during these activities, implemented through case studies and project-based activities (2012), problem-solving, or generally problem-based activities (Asef-Vaziri, 2015). Hands-On Experiences Since blended learning is not limited by the classroom setting, exposing students to handson experiences in industry settings provides highly valued experiential learning (Green, 2015). In fact, several important studies are highlighting the importance, value, and relevance of learning that occurs as the outcome of relations between higher education institutions and industry, pointing specifically to the value of daily work perceived as a learning opportunity (Fleck, 2012). This is further emphasized by Cooper et al (2010), who claim that learning integrated with work is an example of a learning strategy that is created to address well the industry demands through experiential learning. Blended learning faceto-face activities can also facilitate hosting industry guest experts to lead hands-on workshops providing first-hand knowledge and expertise, thus enriching learning while leveraging on direct links between practical work experiences and lecturing content taught (Kjaergaard, 2017). Collaborative Work Face-to-face activities in blended learning that stimulate peer-to-peer interaction during hands-on activities are perceived as relevant in blended learning. Face-to-face experiential activities that enable the application of theoretical knowledge and fall under this category include laboratory/workshop exercises and skill practicing activities that are usually conducted in groups as specific problem-based activities. These activities are usually based on hands-on interaction, dialogue, communication, debate and discussion among peers (Asef-Vaziri, 2015; Fleck, 2012). Onsite practical workshops would be a good example of such activities (Kjaergaard, 2017). According to the WHO, to have the best value as the 22 outcome of group interactions and peer work, it is significant that the onsite face-to-face sessions are delivered as short–term workshops, that are followed-up with online reflection modules of training (World Health Organization, 2019). Green (2015) emphasizes that willingness to share as well as social engagement are exceptionally important in the face-to-face part of blended learning. Kjaergaard (2017) concludes that peer collaboration, team-based activities, and group work, in general, are relevant face-to-face activities in the blended learning approach. Simulations Games, simulations, and role-play activities are also important experiential face-to-face activities in blended learning. Usually, these activities are used to exercise a real-world situation set in a safe environment in which learners could, for example, simulate entrepreneurial behavior or other market activities. Role-playing situations can also be used by learners to test out certain strategies or situations (Green, 2015) or by exercising their potential real-work roles. (Kjaergard, 2017). This is confirmed by Green (2015), who claims that a good way to conduct hands-on practical face-to-face activities in blended learning is through role-plays or project work. 5.4 Online Component of Blended Learning 5.4.1 Characteristics Freeing classroom time by posting content online provides learners with more flexible schedules. This flexibility means that students are provided with a certain level of power that enables them to direct themselves in terms of when, where, how, and at what pace they conduct learning. Namely, students can manage time as it suits them for all online activities that are not taking place in real-time. In terms of location, online learning provides students with strong elements of flexibility, enabling them to study from anywhere as long as they have access to internet connection. Flexibility in the online segment of blended learning is also reflected in the learner’s ability to determine their own pathway and study at their own pace (Boelens et al, 2017). This enables students to have some ownership in the learning path. Consequently, when creating online activities and resources, it is important to keep in mind that not necessarily does the teaching content have to fit all students equally. Rather, the content provided for an average student can be 23 increased for students who need more challenging content or reduced to students who have lower background knowledge (Buban et al, 2019). Another important characteristic of online learning are challenges related to establishing and maintaining group cohesion among peers, a well-connected emotional and social environment ensuring that students participate actively and comfortably in the virtual environment. This is especially important considering that involvement is perceived as an essential element contributing to the effective outcome of the learning process (Kjaergard, 2017). According to a study on social presence in online learning, students indicate their highest satisfaction when social presence is on a high level (Green, 2015). Kjaergard (2017) concludes by stating that making a close social community that presents the foundation of teamwork, discussion, debate, and peer-to-peer learning is important. Similarly, having to deal with educational content physically isolated and without the direct support of the lecturer or other direct social contacts, may also be found challenging for some students, especially those who are not highly motivated or students who are just starting with their university studies (Snowball, 2014). Therefore, it is important to mention that there is a necessary set of skills and requirements that each student should possess to ensure effective participation and self-directedness in the online part of blended learning. This includes effective time management, discipline, self-control as well as a certain level of IT skills (Bocconi & Trentin, 2015). 5.4.2 Online Activities and Tools Blended learning environments enable the use of online tools and communication technologies that guide and develop students, even when outside of the physical teaching environments. These tools and communication technologies facilitate the implementation of asynchronous and synchronous learning activities and often include all-encompassing learning management software systems and other online applications and services that assist collaboration, creativity, sharing, and acquisition of new knowledge. Although these tools and technologies represent new opportunities, it is crucial to understand how learning objectives are complemented with tools and technology available in order to provide learners with adequate facilitation that synchronous and asynchronous elements of online learning can provide (Buban et al, 2019). 24 5.4.2.1 Synchronous According to Bower et al., (2015), synchronous learning can be defined as "learning and teaching where remote students participate in real-time classes utilizing rich-media synchronous technologies such as video conferencing, web conferencing, or virtual worlds" (p. 1). Synchronous learning utilizes a range of different technologies to support live online collaboration, peer-to-peer learning through interaction, problem-solving, debate, discussion, and so forth (Hrastinski, 2019). The different types of communication technology in synchronous learning require different levels of technological complexity and range from simple one-to-one consultations with the teacher and group live web conferencing classes, to collaborative learning combining physical and virtual worlds (Hrastinski, 2019). Although it does not provide as high of a level of flexibility as asynchronous learning, it still provides greater flexibility and accessibility compared to traditional onsite courses. Lectures can be followed from anywhere as long as learners are provided with an internet connection. Another advantage of synchronous learning is cost‐effectiveness. Namely, students do not have to commute daily to campuses, while being able to work together in live scenarios with peers. Web conferencing tools also provide students with the opportunity to view recorded live sessions in case they are absent (Serrano et al, 2019). Examples of synchronous tools include web conferencing tools (e.g. Adobe Connect, GoToMeeting, Microsoft Teams…), Voice-Over-IP (e.g. Skype, WhatsApp…), chat, instant messaging, and so forth (Vaughan, 2013). 5.4.2.2 Asynchronous Asynchronous learning is based on flexible learning that provides students with the opportunity to study not only at their place of choice but also at any time they choose and at their own pace (Serrano et al, 2019). Typically, the asynchronous content that is shared with students before live online lectures or face-to-face activities includes lecturing content and supplementary materials that contain pre-recorded lecture videos, audios, readings, excerpts, presentations (Green, 2015). An important advantage of having content provided online is that students can go over the lectures as many times as they need to. It is important to mention that the use of asynchronous tools does not mean that interaction with peers and group work is no longer possible. It means that these interactions do not 25 have to happen at the same time (Buban et al, 2019). It enables students to actively participate in collaborative work with peers according to their own schedules, enabling structured group learning processes, which, otherwise, might be difficult as physical classrooms and physical places for collaborative learning at times are limited (Bocconi & Trentin, 2014). Asynchronous learning also provides students with the ability to follow education from great distances away and from the physical places of study they choose themselves, making it easier to incorporate higher education with their daily work and family obligations (Buban et al, 2019). Its affirmative impact can most be seen with selfmotivated learners (Serrano et al, 2019). Examples of asynchronous tools are discussion forums, emails, and wikis, while chats and text messaging, social media, collaborative document platforms (i.e. Google Docs) are perceived as tools that can be used synchronously and asynchronously (Buban et al, 2019). Asynchronous learning also has its shortcomings. This is reflected most often in learners' decreased engagement due to reduced opportunity to have face-to-face peer-to-peer and student-to-teacher interaction. Another challenge is that some learners are unable to structure themselves effectively around the learning process, having in mind that learners themselves are responsible to manage their time and work on the course content (Broadbent, 2017). 5.5 Blending Face-to-Face with Online The most important aspect to look into while preparing a blended learning program is how to integrate face-to-face with online parts of learning. According to Garrison and Kanuka (2004), it is crucial to establish the "thoughtful integration" between face‐to‐face and online components (p. 96). As opposed to direct classroom lecturing, perceived as passive (Green, 2015, p. 182), blended learning creates the environment that enables the shift of the direct lecturing content online thus providing space for a different approach to learning onsite. According to Bocconi and Trentin (2015), a frequent motive to move educational programs to blended learning, in fact, is being able to free classroom time for more face-toface interaction through discussions and the application of acquired theoretical knowledge. According to Russell-Bennett et al., (2010), providing learners with lectures ahead of faceto-face classes facilitates self-directed learning, which, according to Green (2015), becomes an effective method of learning, only when taught in combination with face-toface learning using hands-on interactive problem-based activities. This is supported by the 26 US Department of Education report (2010), claiming that students' ability to have face-toface classes, in which interactivity and knowledge are applied, is one of the most important variables leading to the effective blended learning environment. The report also claims that the lecturer in blended learning is expected to limit all the onsite teaching that can be conducted autonomously by the student using digital platforms (direct lecturing, reading, videos and other forms of explicit knowledge usually taught through textbooks), thus creating time in the classroom for more profound approaches to learning that may include further clarifications or transmitting of lecturer's specific and applicable know-how onto students in the class, which generally cannot be taught through direct lecturing (U.S. Department of Education, 2010). It is important to mention that this model creates a mutual expectation from both, the student and the lecturer. Namely, students are expected by the lecturer to come to the class having read and prepared themselves with the lecturing content, while students, on the other hand, expect the lecturer to facilitate the class focused on problem-based and problem-solving activities, interactive discussions, time for questions, collaborative peerto-peer work as well as other activities reflecting the experiential model of learning. This approach enables students to develop their own knowledge from engaging in interactions with peers and the lecturer experientially, instead of being instructed and directed on what to do and learn (Green, 2015). 5.6 Blended Learning as Adult Learning Concept According to McKenna et al., (2019), blended learning is perceived as an advantageous methodology to adult learners due to the different modalities it offers. Rachel claims that all the core andragogical principles are applicable in blended environments, allowing learners a certain level of control (as cited in Youde, 2018) while being able to self-direct (Youde, 2018). Similarly, Merriam and Bierema claim that the focus of blended learning is on the adult learners' internal motivations, self-directed approach, as well as readiness to learn (as cited in McKenna, 2019). McKenna (2019) claims that a requirement for adult learners to succeed is to have autonomy on when, how, and what to learn, which can be facilitated with blended learning as the concept. When it comes to the adult learning principle of relevancy, it is important not to only consider the “need to know” aspect of it, but rather look at it from the perspective of 27 relevancy in providing adult learners with the ability to overcome physical and time constraints. Namely, “the blended format, with its decreased hours in the classroom, can more effectively meet the needs of students with work and family obligations” (Korr et al., 2012, p. 4). Having the opportunity to attend classes from any place and at the time suitable to the learner, makes handling family, work, and school obligations easier (Shea, 2007). “This flexibility has been cited as a key factor in empowering many adult students to remain in school and finish their degrees” (Korr et al, 2012, p. 4). 5.7 Flexibility Flexibility for learners is frequently cited as an important reason why schools decide to transfer to a blended learning approach (Boelens et al, 2017). According to Cook, Pachler, and Bachmair (2011), blended learning offers unprecedented opportunity and flexibility "that stimulate students' ability to operate successfully in, and across, different contexts, utilizing their everyday life-worlds as learning spaces" (as cited in Bocconi & Trentin, 2014, p. 517). The European Commission survey, implemented for the Digital Action Plan of the European Union for 2021-2027, confirms the above statements. According to the survey, the main advantages of combining face-to-face learning with the online segment of education were flexibility and learning at own pace with 70.2% of survey participants, followed by face-to-face communication and interaction by 63.5% of participants, while the integration of innovative practices placed as the third most important advantage expressed by 58.2% of respondents (2020). On the other hand, it has been found that increased flexibility and learner control, although highly beneficial for students who are self-directed and high achievers, may be challenging for low achievers, as the approach depends heavily on independent learning. 5.8 Conclusion – Blended Learning Elements of Flexibility According to Ginsberg and Wlodkowski (2010), “blended learning is relevant to the life circumstances of adult learners by increasing their access to higher education”. It is facilitated by its flexibility, “cited as a key factor in empowering adult students to remain in school and finish their degrees” (Korr et al, 2012, p. 4). Horn & Staker (2014) specify that flexibility provided by blended learning implies that learners have a certain level of influence over time, place, path, or pace of learning. 28 These elements of flexibility are also identified in the definition of blended learning, as used by the European Commission. According to the definition, blended learning is defined as an “approach mixing face-to-face and online learning, with some element of learner control over time, place, path, and pace” (European Commision, 2020). Therefore, it can be deduced that time, place, path, and pace are key elements of blended learning flexibility. To address the second research question and facilitate the further research process, these four elements are divided into three categories and their subcategories as follows: 1. Time and Pace (flexibility in terms of) a. program length b. face-to-face aspects of blended learning c. online aspects of blended learning 2. Place (flexibility in terms of) a. face-to-face aspects of blended learning b. online aspects of blended learning 3. Path These three categories and its subcategories represent the second frame of the research, which is to identify and analyze their presence in the selected graduate blended learning programs. 29 6 Research Methodology The study will be conducted as a mixed quantitative and qualitative research based on textual content collected from the official webpages of the selected European business school MBA/EMBA programs. 6.1 Data Collection Method To be selected, the business schools hosting the graduate programs had to meet the following requirements: 1. Be ranked among the top 100 European business schools according to the Financial Times ranking for 2019 2. Provide MBA or EMBA program delivered with blended learning methodology A total of fourteen schools fulfilled the requirements. The schools originate from six countries as follows: six from the UK, two from Spain, two from Germany, one from the Netherlands, and one from Italy. Two programs are co-hosted by business schools from different countries. One program is co-hosted by business schools from France, the UK, and the US, while the other program is co-hosted by business schools from France, UK, Germany, Spain, Italy, and Poland. 6.2 Data Analysis Method 6.2.1 Content Analysis According to Denzin & Lincoln (2018), content analysis is a common method of research, used extensively in media studies and social sciences, while Krippendorff (2018) states that content analysis is a method of research most used in analyzing social or economic data of business studies. Krippendorff (2018) defines it as “a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts to the contexts”, whose purpose is to approach analysis in an observational, systematic, and objective manner for qualitative and quantitative research (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018). Suitable forms from which data is collected and analyzed can be books, web pages, magazines, speeches, letters, newspapers, paintings, email messages, and so forth. When gathered, the content is coded into different categories or concepts depending on established criteria. The coding can be conducted either manually or assisted by computers (Babbie, 2020). 30 According to Krippendorf (2019), there are three different starting points for content analysis: text-driven, problem-driven, and method-driven. The text-driven approach is incited by the richness of textual content itself, which serves as the basis of the research. The text itself stimulates the researchers’ interest. In the problem-driven approach, analysis is motivated by epistemic questions of not knowing something perceived as relevant, such as unknown processes, events, or other phenomena. The objective of this method is to attempt to establish an understanding of an issue seen as inaccessible. The research question is the basis of the research. The third approach is method-driven and it is motivated by the analysts' aspiration to apply existing analytical processes in the fields previously explored differently (Krippendorf, 2018). Similarly, Hsieh and Shannon (2005), categorize content analysis into three models: conventional, directed, and summative. All three models attempt to decipher data from the textual content. The main difference between the three approaches is in the development of initial codes. The conventional content analysis focuses on data that is acquired during analysis. In the directed content analysis, the analyst uses existing theories to establish coding schemes before starting data analysis. Lastly, the summative approach is frequently conducted using single words for analysis of patterns, leading to establishing interpreted contextual meaning of the content (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). From the different perspectives presented above, problem-driven content analysis by Krippendorff and the directed content analysis by Hsieh and Shannon both seem feasible options in this thesis. However, I believe that the directed content analysis is best suited as it uses existing theories as the basis for the research. 6.2.2 Directed Content Analysis The directed content analysis enables the analyst to create the research question through existing theories. It also enables the analyst to establish the relationship between different variables and sub-variables assisting the establishment of initial categories and relationships between categories. Hsieh and Shannon (2005) refer to this aspect as the deductive application of categories. In directed content analysis, the results may be either supportive or non-supportive of initial theories, while findings may be presented either through codes or descriptions. In discussion and analysis of collected data, prior theories 31 and research provide guidance. The theories can be expanded and further supported based on the outcome of the analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). 6.2.3 Limitations of Research Design The main limitation of content analysis comes from the very nature of the research method. Namely, it may be the case that content analysis does not take into account any other meaning except the data directly collected through coding. Consequently, the outcome of the analysis is highly trustworthy, however, the results of the analysis are an outcome of a merely automated process, thus questionable. This is specifically the reason why Denzin and Lincoln (2018) believe the quantitative content analysis shall not be used as the only aspect of content analysis. However, this shall not represent a challenge in my approach due to the inclusion of the qualitative content analysis as well. Furthermore, using analysis based on theory may lead to certain limitations reflected in the impartial dealing of analysts with data. Namely, the theory may guide the analyst more towards supportive as opposed to non-supportive evidence. The strong emphasis on theory may also prevent the analyst from seeing other contextual aspects of the phenomenon in question (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). In this study, I attempted to address this issue by examining each topic from several different angles, providing also positions of critique. 6.2.4 Implementation Process Content analysis that utilizes a directed approach is guided by a structured process. Following the directed content analysis, the process in this study is initiated by the identification of existing theories and researches to identify key techniques and elements. This is followed by operationally defining each of the categories and subcategories based on the identified techniques and elements. In the following step, all the relevant text is systematically identified, marked, and transferred into a table, thus ensuring that all possible occurrences of codes are captured in order to increase trustworthiness. This is followed by quantitative and qualitative analysis. 6.2.5 Implementation Practicalities The sources of data collection were official webpages of the selected MBA and EMBA programs. All the data was accessed during the period from November 15, 2020 and December 15, 2020. For each MBA/EMBA program, the official brochure was first 32 analyzed, and then the rest of the business school’s webpage pertaining specifically to the MBA/EMBA program in question. All the official brochures were downloaded from the official program webpages. As deduced from theory, two frames with their accompanying categories and subcategories were used in the data collection process. The first frame consisted of four categories of teaching techniques, as follows: 1. Category 1: Case studies 2. Category 2: Simulations 3. Category 3: Collaborative work (peer-to-peer learning, group work, discussions, debates) 4. Category 4: Hands-on experience (laboratory/workshop experiences, on-the-job experience, internships, hands-on practice sessions) The second frame consisted of three blended learning elements of flexibility with its subcategories, as follows: 1. Category 1: Time and Pace (flexibility in terms of) a. Subcategory 1a: program length b. Subcategory 1b: face-to-face aspects of blended learning c. Subcategory 1c: online aspects of blended learning 2. Category 2: Place (flexibility in terms of) a. Subcategory 2a: face-to-face aspects of blended learning b. Subcategory 2b: online aspects of blended learning 3. Category 3: Path During data collection, each category and subcategory identified was marked with a YES. If further elaboration on the topic was identified, additional statements were recorded as well. If the category or subcategory was not identified, it was marked with a NO. All the identified data was first systematically underlined and highlighted in the brochure or copied from the webpage into a document containing the collected data, school by school, program by program. All the data was afterwards transferred into an Excel document. Finally, all the narrative statements pertaining to relevant categories and subcategories were transferred. 33 The list of all official business school webpage addresses of all the business school programs in the research, from which all the brochures were downloaded and the rest of the data collected, can be found in Appendix C, while the consolidated table with the data collected can be found in Appendix A for Frame 1 and Appendix B for Frame 2. 34 7 Findings and Analysis I will first present and analyze the findings quantitatively, using descriptive statistics, and qualitatively, following the directed approach, for each category and subcategory. I will follow the same structure as described in the data collection method. 7.1 Frame 1: Teaching Techniques 7.1.1 Category 1: Case Studies Case studies were identified in ten out of fourteen programs. In five out of the ten, case studies were only taken note of, without any further elaboration. In the remaining five, all coming from different programs, additional statements were provided as follows: Program 1: “Case Study Method: You will hone your critical thinking and decision-making capabilities by analyzing real-world business challenges and outlining a course of action among a pool of equally plausible solutions.” Program 2: “Engage with other global professionals in synchronous and asynchronous sessions including interactive small groups where you work on real-world, industry-based case studies.” Program 3: “Application of knowledge to real-world case studies.” Program 4: “ Engage in real-life case studies and gain new tools to help propel your career and drive change in your chosen industry.” Program 5: “Work in groups to apply theory to case studies based on real business problems.” In all five programs, the emphasis of case studies is on experiential real-life scenarios, reflected through wording “real-world”, “real-life”, “real-business problems”, “industrybased”. These phrases emphasize the importance the programs are putting on the application of theory to real-life situations. It is also in line with adult learning principles of prior experience, readiness, and relevancy. More specifically, according to Knowles 35 (2005), adult learners represent a valuable learning source that assists the learning process in a number of activities, especially applicable in case studies. The principle of readiness, according to Knowles et al (2015), comes out of the need of adult learners for knowledge that is required to deal with a certain real-life situation. This implies also that the lecturers, when preparing, should prepare content that is as relevant as possible concerning direct applicability in real life, which, as could be seen from the statements above, is present in all the identified statements. Furthermore, relevancy, recognized as a problem-oriented attempt to acquire the knowledge needed to address a specific problem, is also present, since case studies focus on specific challenges applicable in real life. 7.1.2 Category 2: Simulations Simulations were identified in five out of the fourteen selected programs. In one program, simulations were only taken note of, without any additional elaboration. In the remaining four, the statements are as follows: Program 1: "Simulations and role-plays: Realistic test environments, complete with time constraints and opposing power sources, will advance your executive and communication skills" Program 2: "You will work with your group online and take part in a WBS built simulation where you complete tasks as if solving real-life company issues" Program 3: "With essential performance feedback from the simulator, we’re able to target and train advanced communication techniques to refine visible authenticity in your leadership skillset" Program 4: “Test yourself with a simulation project based on global business and management challenges. The simulation project will challenge you to rigorously analyze and overcome business problems. You will apply knowledge and skills from different areas of business and management, experience the interdependencies in decision making in an organization, explore the dynamics of working in multicultural groups with colleagues from diverse professional backgrounds.” 36 In three out of four statements, the emphasis is on the experiential application of acquired knowledge implemented through simulations of real-life situations. This is identified in the following phrases: “apply your knowledge”, “experience your interdependencies”, “test yourself”, “as if solving real-life company issues”, “realistic test environments” “complete with time constraints and opposing power sources”. Similar to results in case studies, these statements incorporate elements of adult learning principles of prior experience, readiness, and relevancy. These three principles of adult learning are recognized on the same basis as explained above for the category case studies. One of the statements addresses the use of simulations for the improvement of communication skills. Elements of adult learning principles have not been identified in this statement. 7.1.3 Category 3: Hands-On Experience (workshops, on-the-job experiences, internships) Hands-On Experiences were identified in twelve programs. Statements identifying handson experiences are as follows: Program 1: “Capstone Project is an opportunity to apply your program learning to your current business environment, a start-up, or a social cause.” Program 2: “In Company Project - working in teams with a sponsoring company, you will identify a real-life challenge and build an actionable plan to address it.” Program 3: “Advanced multi-platform learning environment. Thanks to this unique approach, which combines interactive courses with practical, hands-on experiences, you can learn in the same way you work.” Program 4: “The modular format means you apply on-campus learning, new ideas, and approaches in your day-to-day work immediately – putting theory into practice with real-time impact.” 37 Program 5: "Designed to provide participants with a collaborative, multidisciplinary, and intercultural work experience on a real-life strategic challenge. The 12-month International Consultancy Project (ICP) puts into practice the concepts and theories acquired during the EMBA. Within a group, you will perform an in-depth analysis of a challenge faced by a company and make recommendations for actions that can be realistically implemented by the client firm." Program 6 “Your dissertation will allow you to apply what you have learned during your MBA to a real management issue in practice.” “You are required to source your own project, so this is often from your own organization. However, if you are interested in changing either your functional role or the sector that you work in, you can use your dissertation as a steppingstone to transition by working on sourcing a project for a different organization or within a new functional area.” Program 7 “Studying and working simultaneously means that you will immediately apply your learnings to your organization. “ Program 8 "In-company project: the course is structured to allow you to continue to work full-time and study your MBA part-time, connecting your learning to current and relevant organizational issues.” “Our MBA programmes combine the best in academic theory with practical, reallife projects." Program 9 “Shape your experience by exploring a business challenge in your own organisation, or an entrepreneurial opportunity in a sector of your choice. “The project is a great chance to: Test your next career move in a live business environment or gain experience in a new sector.” “Apply the knowledge you have acquired to solve a real business problem.” Program 10: “You continue in full-time employment, so you can apply what you learn directly into the organisation you work for.” 38 Program 11: “Real business innovation or entrepreneurial development project, in which the concepts learned in the Master can be applied to a concrete business case.” “The Business Transformation Project represents an excellent opportunity to realise consulting projects in your company or to develop a new business idea.” Program 12: “We collaborate with leading companies and entrepreneurs to challenge you to tackle real-world problems throughout your program.” Program 13: “MBA that enables you to immediately apply what you learn to your daily working life. Hult’s Live Online MBA ensures you are best placed to lead in this reality as you learn by doing.” Program 14: "Business consulting project - at the end of your MBA you will translate your learnings into a final project that addresses a real and current management problem in your organization.” In this category, four programs have an immediate application of knowledge at a student's place of work advertised as hands-on experience, but without elaborating on how it is conducted. No structure behind it has been identified (e.g. School 13). On the other hand, four programs offer hands-on experiences by providing the student with different options. One of the options in all four schools is to conduct a structured hands-on activity at the student’s place of work. The other options include hands-on activities to choose from such as “entrepreneurial opportunity in a sector of your choice”, “a start up”, or a “social cause”. All four schools have more than two options. Three programs implement hands-on activities in sponsored and/or partner companies as in-company projects. Two programs have in-house hands-on activities. All the programs that offer different options apply the adult learning principle of selfdirectedness enabling the student to choose own path to a certain level. In all the activities presented above, the adult learners should be able to understand why, when, where, and how these learning activities are applied and how they personally contribute, due to the very nature of hands-on experiences. This indicates the presence of the adult learning 39 principle of the need to know. Furthermore, adult learners bring prior experience to the experiential hands-on activities while addressing specific real-life problems either directly applied in real life through the aforementioned activities or potentially applicable to real life situations. This indicates that the adult learning principles of “prior experience”, “readiness” and “relevancy” are identified in the hands-on activities of the selected programs for Category 3 of Frame 1. 7.1.4 Category 4: Collaborative Learning (peer-to-peer, group work, discussions) In this category, at least one of the collaborative experiential learning teaching techniques has been identified in all 14 programs. Nine programs provided further statements about the techniques from this category as follows: Program 1: “Peer-to-peer learning will expose you to new ideas and practices outside your sector and corporate sphere, as well as enhance your professional network.” Program 2: “During each course, you benefit from the flexibility of interactive online learning at your own pace while also learning from your peers and world-class faculty both online and in person.” Program 3: “As a participant of the programme, you will share your experience with a multicultural group of peers, both in terms of nationalities and professional backgrounds.” “Within a group, you will perform an in-depth analysis of a challenge faced by a company and make recommendations for actions that can be realistically implemented by the client firm.” Program 4: “For assessed group work, you will work in teams to investigate an aspect of a module in the real-world and co-create an assessed piece of work on the day.” Program 5: “These modules are all assessed by group projects and you will find yourself working alongside a culturally rich group of exceptional individuals from numerous industries.” 40 "The collaborative, discussion-based format of our classes stimulates networking and idea-sharing that will have a direct impact on your business." Program 6: “Gain global business insights through active dialogue with a diverse group of peers.” “Thrive in a collaborative group setting, where new ideas come to life.” “Study alongside global peers with a mixture of live interactive classes and asynchronous sessions, led by an international faculty and business experts.” Program 7: “Explore the dynamics of working in multicultural groups with colleagues from diverse professional backgrounds.” Program 9: “The online study platform enables intensive interaction with your peer students. Via this platform, you can collaborate 24/7 on projects and exchange experiences. During the three residential weeks, you will meet your fellow students face to face.” In the above statements, all 9 programs indicate peer-to-peer learning. The peer learning experiential activities were described as “knowledge sharing”, “idea sharing”, “experience sharing”, “experience exchange”. “Group” work was explicitly mentioned in five programs. Furthermore, learning from colleagues who come from “diverse professional backgrounds”, “numerous industries”, “culturally rich” “multicultural” backgrounds, and so forth, was identified in 5 programs. Intensive interaction with peers and active dialogue among peers were also mentioned, similarly stressing the importance of peer-to-peer learning. Additionally, networking was mentioned in 3 programs. All of Category 4 activities of Frame 1 indicate the application of the andragogical principle of “prior experience”, in which the adult learner’s prior experience is brought into the learning process as the basis for learning and exchange. 7.2 Frame 2: Blended Learning Elements of Flexibility 7.2.1 Category 1: Time and Pace Category 1 of Frame 2 consists of three subcategories, program length, face-to-face, and online flexibility. 41 Subcategory 1a: Program Length Flexibility in Terms of Time and Pace In this subcategory, eight programs indicated some level of flexibility. Students in the remaining six do not have an option to adjust the program duration. The duration of nonadjustable programs is 16 months, 18 months, 23 months, two programs 24 months, and 30 months. I divided the programs that provide students with flexibility in terms of their ability to choose program duration into three groups: programs with two preset tracks, programs with three preset tracks, and programs with the adaptable format, providing learners with a flexible period within which the program is to be completed. Programs with Adaptable Format Five programs offer an adaptable format. Two schools provide students with the option to choose between 24 to 48 months, with the following statement: “We’ve built the Distance Learning MBA with flexibility in mind. This means that when your job needs to take precedence for a while you can choose to slow down or take a break of up to two years before continuing your studies. You may complete your Distance Learning MBA in two to four years depending on your personal circumstances.” Another program offers flexible program duration from 20 to 48 months, stressing that, although 20 months is considered an expected standard, students are provided with the option to spread the program up to 48 months as they think it best fits their personal needs. One program offers two track options of 18 or 36 months but also provides the student with the opportunity to extend it up to 60 months if needed. This program also annotates that in the fast track of 18 months, the weekly expected student time investment is 18.5 hours, which is reduced down to 9.25 hours if the 36-month track is taken. Lastly, one program also provides students with the possibility to choose program duration from 18 to 36 months, adding that 24-month is the track that they consider normal but that anywhere from 18 to 36 is possible. 42 Two-Preset-Track Programs Two programs offer two preset tracks as options. One program offers the program to be completed in 17 or 24 months (with an optional 7-month semester added at the end of the 17-month program), while the other one offers the program to be completed either following the 18-month "accelerated” track or 24-month “normal” track. Three-Preset-Track Programs One program offers three possible preset tracks of 18, 22, or 30 months. The above data indicates that the programs are providing adult learners with significant flexibility that facilitates increased access to higher university education. The access is increased by providing students with possibilities that enable different levels of flexibility timewise and in terms of pace. This flexibility enables the adult learner to more easily handle different spheres of their life, education, work, and family obligations, while stressing the andragogy principle of relevancy. It also addresses the adult principle of selfdirectedness as different program lengths provide the adult learner with some ability to self-direct parts of the program, as indicated above. Subcategory 1b: Face-to-Face Flexibility in Terms of Time and Pace Flexibility in terms of time and pace related to the face-to-face components of blended learning is very low considering that only two of fourteen programs provided some level of flexibility to students. These two programs provide an option to choose when to attend face-to-face activities. The flexibility provided by this segment of blended learning is very low. However, this may point to the fact that face-to-face activities, being significantly shorter than online part of the education in the vast majority of the selected blended learning programs, are considered highly important and rare opportunities to implement a number of relevant teaching techniques and activities. As it could be seen in the blended learning part of the thesis "Face-to-Face Learning Activities and Tools", all four key teaching experiential techniques are important face-to-face activities of blended learning. Other important activities such as networking events, company visits, company fairs, and so forth, also bring the most value if implemented face-to-face. This is also confirmed in the European Commission survey where the majority of respondents, as the follow-up to the questions 43 on advantages of blended learning, described physical presence as ‘unreplaceable’ (European Commission, 81). Therefore, the value that these key techniques and activities requiring onsite presence bring is likely considered significantly more important than providing time and pace flexibility for face-to-face activities. Subcategory 1c: Online Flexibility in Terms of Time and Pace All fourteen programs provide online flexibility in terms of time and pace for all aspects of online education, except for the synchronous live lecturing / conferencing with students. One program stresses that all live sessions are also recorded to provide students with additional flexibility by enabling them to view the lectures at a later stage, while another program emphasizes that their online live sessions have schedules for five different timezones to ensure reasonable timing of life sessions for all students in the program. The outcome of this subcategory strongly points to the flexibility that the online part of blended learning provides, enabling the adult learner to access more easily higher education by being able to arrange work, family, and education obligations, due to reduced requirement for class presence at specific times. The ability to choose own time for studies applies the adult learning principle of self-directedness. The andragogy principle of relevancy is applied by providing students with “decreased hours in the classroom” which “can more effectively meet the needs of students with work and family obligations” (Korr et al., 2012, p. 4). Having the opportunity to attend classes from any place and at the time suitable to the learner, it is easier to handle family, work, and school obligations (Shea, 2007). "This flexibility has been cited as a key factor in empowering many adult students to remain in school and finish their degrees” (Korr et al, 2012, p. 4). 7.2.2 Category 2: Place (flexibility in face-to-face, flexibility online) Category 2 of Frame 2 consists of two subcategories, face-to-face flexibility, and online flexibility. Subcategory 2a: Face-to-Face Flexibility in Terms of Place Six programs provide some element of flexibility in terms of place. Two programs provide students with the option to select the place of electives workshops, options being 5 or 6 44 different cities located across the globe. Three programs provide the option of choosing elective or optional workshops online or onsite. For three programs, all onsite activities can also be conducted online. One program has the option of changing the location of studies to 5 different places across the globe in case of student relocation, while another program has the option of following the first face-to-face induction week online. The programs offering face-to-face flexibility in terms of place, whether it be for elective courses, or giving more places as options for face-to-face events, may also provide for easier access to higher education. It also applies the andragogy principles of relevancy and self-directedness, as explained in the previous subcategory. Subcategory 2b: Online Flexibility in Terms of Place All 14 programs provide flexibility in terms of place when it comes to online aspects of blended learning. This enables easier access of adults to higher education while applying the adult learning principles of relevancy and self-directedness, as explained in Subcategory 1c. 7.2.3 Category 3: Path A certain level of flexibility in terms of student ability to select own pathway and customize their programs was identified in twelve out of fourteen programs. Nine programs provide different modes of optional learning activities ranging from optional elective online or face-to-face modules, abroad or at school, to optional residencies and workshops held at different global locations. Eight programs provide students with options to choose electives on-campus or online. Some programs provide a wide variety of electives to choose from. The number of offered elective courses ranges from school to school (from 6 courses in one program to over 50 in another, including 10-12, 30, and 35, in the rest of the programs). One program provides 4-week on-campus electives, based on student selection. Examples of school statements related to the selection of electives are as follows: Program 1: “Personalize your studies by selecting elective courses relevant to your interests and participate in an optional face-to-face module abroad to discover new markets.” 45 Program 2: “There are a range of elective modules to allow you to specialize.” Program 3: “A third face-to-face week is elective, and student can choose among a Management Bootcamp, an Elective Course of the Executive MBA, a Doing Business In China or Mexico, or a Study Tour in Silicon Valley." Program 4 “Degree can be personalized with a wide range of electives and seminars offered in both 3-day weekend and longer formats at Hult campus locations across the globe.” Students in four programs can choose from a number of preset specialization or project tracks. One program provides students with an option to choose between the entrepreneurship or intrapreneurship track. Another program provides three options, entrepreneurship, consultancy, or technology: "Pathway in either entrepreneurship, consultancy, or technology. Each Pathway includes two academic modules, skills workshops, and strategic insights provided by industry experts. The Pathways provide an excellent opportunity for you to develop your knowledge, skills and capabilities in a specific area most suited to your own professional needs." One school provides two paths, innovation or digital transformation. One more school enables different preset pathways: “You can also personalise your programme by completing a Pathway choosing a combination of optional modules which align with your career ambitions and goals.” One other program provides flexibility in terms of the path by providing students with the option to take courses in any order: “our flexible modular online courses allow you to complete the programme in any order you like.” 46 As shown above, there is a variety of options provided by business schools pertaining to the students' ability to personalize their studies. These options provide the learner with opportunities to study what is the most relevant to their personal circumstances, aligning "with your career ambitions and goals” and “in a specific area most suited to your own professional need”. The ability to create personalized pathway of learning is in line with the adult learning principles of "self-directedness". The ability to customize the learning pathway also applies the andragogy principle of "relevancy" as it facilitates creation of a pathway that is more closely related to the specific challenges that the adult learner is attempting to address. It is also relevant in terms of facilitating better harmonization of work, family and school obligations by providing the adult learner with more options. Lastly, the principles of “readiness” and “need to know” are also applied as the options for own pathway since it is shaped by the learners’ specific needs. Also, choosing their own pathway may contribute to the increase of adult learner accessibility to higher education by attracting more adult learners as it enables them to customize their learning pathway, making it as applicable as possible to their real-life needs and circumstances. 7.3 Overall Findings and Analysis 7.3.1 Frame 1 Category Identified in: 1. Category 1: Case Studies 10/14 2. Category 2: Simulations 5/14 3. Category 3: Collaborative Work (peer-to-peer learning, 12/14 group work, discussions, debates) 4. Category 4: Hands-on Experience (laboratory/workshop 14/14 experiences, on-the-job experience, internships, hands-on practice sessions) Table 2. Frame 1 Results 47 The overall numbers for Frame 1 indicate that the experiential teaching techniques, apart from Category 2 – Simulation which is identified in 5 out of 14 programs, are highly present in the 14 selected blended learning programs, ranging from 10 to 14 programs. These numbers indicate that the majority of graduate blended programs of leading European business schools use three of the key experiential teaching techniques, while somewhat under half of the selected fourteen programs use simulation in their programs. This provides the answer to the first research question. The overall findings further indicate that blended learning programs of leading European business schools apply adult learning principles: need to know, self-directedness, prior experience, relevance, and readiness, through the use of experiential teaching techniques, as deduced from theory, with the strong focus on real-life or simulated hands-on experiences through problem-based collaborative efforts, thus contributing to improved learning outcomes, in line with the needs of adult learners. 7.3.2 Frame 2 Category Identified in: 1. Category 1: Time and Pace Flexibility a. Subcategory 1a: program length 8/14 b. Subcategory 1b: face-to-face aspects of blended 2/14 learning c. Subcategory 1c: online aspects of blended 14/14 learning 2. Category 2: Place a. Subcategory 2a: face-to-face aspects of blended 6/14 learning b. Subcategory 2b: online aspects of blended 14/14 learning 3. Category 3: Path 12/14 Table 3. Frame 2 Results 48 The overall numbers for Frame 2 indicate a high presence of blended learning elements of flexibility. More specifically, apart from Subcategory 1b identified in only 2 programs, the rest of the categories and subcategories are quite strongly present in the selected graduate programs. They range from elements of face-to-face flexibility in terms of place identified in 6 out of 14 programs, followed by elements of flexibility in program length identified in 8 programs, and elements of flexibility in having a certain level of control in determining own path identified in 12 out of 14 programs. Moreover, the subcategories 1c and 2b, indicate that elements of flexibility in terms of time, pace, and place of online aspects of blended programs, have been identified in all fourteen programs. The overall numbers indicate that blended learning elements of flexibility are identified in all selected programs, thus providing the answer to the second research question. The overall results indicate that the programs are providing adult learners with significant flexibility. Learners are provided with a significant number of different possibilities enabling different levels of flexibility timewise, as well as in terms of pace, place, and path. This flexibility enables the adult learner to handle different spheres of their life more easily by/while being able to have a considerable impact on the pathway of their studies. The elements of flexibility further enable the application of adult learning principles of relevancy, self-directedness, readiness, and need to know, at varying levels. Considering all of the above, it may also be concluded that the identified blended learning elements of flexibility may facilitate increased access of adult learners to higher university education, thus confirming the claims of Ginsberg and Wlodkowski (2010) and Boelens et al (2017), that blended learning methodology is relevant to adult learners’ circumstances of life because it assists them by enabling increased access to higher education (2010), facilitated by its flexibility, cited as a key factor in empowering many adult students to continue their studies and graduate. 49 7.4 Key Takeaways Based on the data findings and analysis, I would like to draw attention to the key takeaways I have identified: 1. The analyzed programs use the identified techniques extensively in the application of theory by focusing on real-life scenarios. 2. The adult learning principles of need to know, self-directedness, prior experience, relevance, and readiness are applied in most of the selected programs. 3. Collaborative peer-to-peer work is the preferred method of learning when using experiential teaching techniques. 4. The face-to-face component of blended learning is necessary for the delivery of the identified teaching techniques. 5. The online aspects of blended learning provide a high level of flexibility. 1. Asynchronous aspects of blended learning provide high flexibility in terms of time and place in all the programs. 2. Synchronous aspects of blended learning provide high flexibility in terms of place for all the programs. 6. The possibility for students to create a certain level of the personalized educational pathway is available in the majority of programs. 7. Program customization allows the application of all the principles of adult learning while/by providing flexibility in terms of path, time, place, and pace. 50 8 Conclusion The aim of this paper was to examine three themes: adult learning principles, experiential learning theory, and the concept of blended learning. The theoretical research first included the examination of adult learning principles, focusing on Malcolm Knowles, which guided the research towards experiential learning, focusing on David Kolb. The research included the review and critique of main principles of adult learning, an overview of experiential learning theory, as well as an examination of experiential teaching tools, elements, and techniques that are in line with adult learning principles of Malcolm Knowles. The outcome of the research led to the establishment of four experiential teaching techniques: case studies, simulations, hands-on experiences, and collaborative work, as highly relevant to adult learners. From this framework stemmed the first research question, guiding the first frame of the thesis: Do existing blended programs implement the four teaching techniques of experiential adult learning, as deduced from theories? Once the experiential teaching techniques became established, the objective was to examine blended learning methodology, its models, characteristics, tools, and elements in order to determine its suitability as a method for the experiential learning of adults. The research also included the review and applicability of these techniques in blended learning. It was established that these four teaching techniques are used in the delivery of blended learning. Further theoretical research identified flexibility as the key benefit of blended learning, particularly relevant to adult learners. This led to the distinguishing of three elements of flexibility in blended learning: time and pace, place, and path. Therefrom stemmed the second research question, guiding the second frame of the thesis: Do existing blended programs implement the three elements of blended learning flexibility, as deduced from theories? By following a mixed-methods approach, this thesis conducted a quantitative and qualitative content analysis following the directed approach by Hsieh and Shannon (2005). The chosen theoretical framework was operationalized in the context of selected business school graduate programs, gathered from the official webpages of the programs in question. 51 By means of quantitative and qualitative analysis, it is evident that all the teaching techniques and elements of blended learning were identified in all fourteen programs, thus providing the answer to both research questions. Based on the research, the core concluding points are as follows: 1. The four techniques of experiential learning, identified as relevant according to adult learning principles, are case studies, simulations, hands-on experiences, and collaborative learning. 2. These techniques have been identified in all 14 leading European blended learning graduate programs. Three techniques (case studies, hands-on experiences, collaborative learning) have been identified in the vast majority of programs. 3. Blended learning is a suitable method for the delivery of the four identified experiential techniques. 4. The elements of flexibility in blended learning are time and pace, place, and path. 5. All these elements of flexibility have been identified in all the programs. 6. Blended learning elements of flexibility may contribute positively to the accessibility of adult learners to higher education. With this knowledge in hand, the objective of this study is to attempt to provide an overview and analysis in order to assist educational institutions in making informed decisions when adopting blended learning methodology, while at the same time addressing the global need for setting an environment that enables adult learners to continually learn, unlearn, and relearn knowledge applicable to their work environments. 9 Limitations and Further Research In the course of the research, I also noted a number of limitations, as potential topics for further research: 1. The research was conducted based on information publicly available online. This information, brochures and websites, are also promotional materials of the programs in question, making it potentially be different than it is in reality, in order to attract target customers. With this in mind, for further research, and to confirm 52 the reliability and trustworthiness of the data collected through websites, a participant observation, survey, or interview method would be suggested. 2. Considering that the adult principle of motivation has not been taken in consideration in this study, due to the lack of sources and resources, while taking in consideration the sound critique, it would be important to further investigate its relevancy for adult learners within blended learning environments. 3. This study did not take into consideration or define the notion of an adult learner. This is relevant information that should be studied in the future in relation to elements of offered blended learning programs. For example, a research comparing blended learning approaches in bachelor vs. master’s degree programs, considering the different target group of adult learners. 4. In line with the previous limitation, the study did not take into consideration that the requirement to be selected in the researched graduate programs was a certain level of prior work experience. In this study, the requirement for all programs was from 3 to 10 years, which, when I realized, was too late to include in the research. The future research may be comparative analysis between blended learning programs that require previous work experience employment vs. blended programs that do not require previous experience. 5. Considering that a significant number of schools consider immediate application of acquired knowledge as part of program’s hands-on experiences, it might be interesting to conduct a research to see how student places of work can be incorporated in a structured manner into the delivery of blended learning programs. 53 List of References AACSB. (2019). A Collective Vision for Business Education | AACSB. https://www.aacsb.edu/publications/researchreports/collective-vision-for-businesseducation Ahn, J.-H. (2008). Application of the Experiential Learning Cycle in Learning from a Business Simulation Game. E-Learning and Digital Media, 5(2), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2008.5.2.146 Asef-Vaziri, A. 2015. The Flipped Classroom of Operations Management: A Not-for-CostReduction Platform. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 13(1): 7189. Babbie, E. R. (2020). The Practice of Social Research (MindTap Course List) (15th ed.). Cengage Learning. Benson-Armer, R., Gast, A., & Dam, N. van. (2016, May 10). Learning at the speed of business. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/ourinsights/learning-at-the-speed-of-business. Bersin, J., Schwartz, J., Pelster, B., & van der Vyver, B. (2017). Rewriting the rules for the digital age. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/HumanCapital/ hc-2017-global-human-capital-trends-gx.pdf Bocconi, S., & Trentin, G. (2014). Modelling blended solutions for higher education: teaching, learning, and assessment in the network and mobile technology era. Educational Research and Evaluation, 20(7–8), 516–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2014.996367 Boelens, R., De Wever, B., & Voet, M. (2017). Four key challenges to the design of blended learning: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, 22, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.06.001 Bower, M., Dalgarno, B., Kennedy, G. E., Lee, M. J. W., & Kenney, J. (2015). Design and implementation factors in blended synchronous learning environments: Outcomes from a cross-case analysis. Computers & Education, 86, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.03.006 Brassey, J., Christensen, L., & Dam, N. van. (2019, February 14). The essential components of a successful L&D strategy. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/theessential-components-of-a-successful-l-and-d-strategy. Broadbent, J. (2017). Comparing online and blended learner’s self-regulated learning strategies and academic performance. The Internet and Higher Education, 33, 24– 32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.01.004 54 Bryan, A., & Volchenkova, K. N. (2016). BLENDED LEARNING: DEFINITION, MODELS, IMPLICATIONS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION. Bulletin of the South Ural State University Series “Education. Education Sciences,”8(2), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.14529/ped160204 Buban, J., Cavanau, T. B., Dziuban, C. D., Graham, C. R., Ko, S., Moskal, P. D., … Ubel, R. (2019). Online & Blended Learning: Selections from the Field. Newburyport, MA: Online Learning Consortium, Inc. Callister, R. R., & Love, M. S. (2016). A Comparison of Learning Outcomes in SkillsBased Courses: Online Versus Face-To-Face Formats. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 14(2), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12093 Cooke, J. C. (1994). MALCOLM SHEPHERD KNOWLES, THE FATHER OF AMERICAN ANDRAGOGY: A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc278013/ Demirer, V., & Sahin, I. (2013). Effect of blended learning environment on transfer of learning: an experimental study. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 29(6), 518– 529. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12009 Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (2018). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (5th ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE. Douglas, I., Noah, O. F., & Williams, B. R.-. (2019). Combining Traditional Face-to-Face Classroom Practices with Computer Mediated Activities for Meaningful Learning Experience. IJARCCE, 8(6), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.17148/ijarcce.2019.8601 Elsten, C., & Hill, N. (2017, September 6). Intangible Asset Market Value Study? SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3009783. European Commission. (2020). Digital Education Action Plan 2020 - 2027: Resetting education and training for the digital age. https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/default/files/document-library-docs/deapcommunication-sept2020_en.pdf Faria, A. J., Hutchinson, D., Wellington, W. J., & Gold, S. (2008). Developments in Business Gaming. Simulation & Gaming, 40(4), 464–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878108327585 Fleck, J. (2012). Blended learning and learning communities: opportunities and challenges. Journal of Management Development, 31(4): 398-411. Garrett, G., Saloner, G., Nohria, N. & Hubbard, G. (2016), The Achievements and Future of Business Education. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 28: 825. https://doi.org/10.1111/jacf.12189 Garrison, D. R., & Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 7(2), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2004.02.001 55 Ginsberg, M. B. & Wlodkowski, R. J. "Access and Participation." In C. Kasworm, A. R. Rose, and J. Ross-Gordon (eds.), Handbook of Adult and Continuing Education. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010, pp. 25-34. Graham, C. R. (2013). Emerging practice and research in blended learning. In M. G. Moore (Ed.), Handbook of distance education (3rd ed., pp. 333– 350). New York, NY: Routledge. Green, T. (2015). Flipped Classrooms: An Agenda for Innovative Marketing Education in the Digital Era. Marketing Education Review, 25(3), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/10528008.2015.1044851 Hans, V., Basil & Crasta, Shawna J., Digitalization in the 21st Century - Impact on Learning and Doing Things (April 2, 2019). Journal of Global Economy, 15(1), 1223, 2019. Hase, S & Kenyon, C (2001), Moving from andragogy to heutagogy: implications for VET, Proceedings of Research to Reality: Putting VET Research to Work: Australian Vocational Education and Training Research Association (AVETRA), Adelaide, SA, 28-30 March, AVETRA, Crows Nest, NSW. Healey, M., & Jenkins, A. (2000). Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory and Its Application in Geography in Higher Education. Journal of Geography, 99(5), 185– 195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340008978967 Henschke, J. A. (2011). Considerations Regarding the Future of Andragogy. Adult Learning, 22(1), 34–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/104515951102200109 Horn, M. B., & Staker, H. (2014). Blended: Using Disruptive Innovation to Improve Schools. San Francisco: John Wiley and Sons. Hrastinski, S. (2019). What Do We Mean by Blended Learning? TechTrends, 63(5), 564– 569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-019-00375-5 Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687 Kjaergaard, A. (2017). Face-to-Face Activities in Blended Learning: New Opportunities in the Classroom? Academy of Management Proceedings, 2017(1), 16717. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2017.16717abstract Knowles, M. S., Iii, E. H. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2015). The Adult Learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development (8th ed.). Routledge. Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: Enhancing Experiential Learning in Higher Education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(2), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2005.17268566 56 Korr, J., Derwin, E. B., Greene, K., & Sokoloff, W. (2012). Transitioning an Adult-Serving University to a Blended Learning Model. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 60(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2012.649123 Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. Kurthakoti, R., & Good, D. C. (2019). Evaluating Outcomes of Experiential Learning: An Overview of Available Approaches. The Palgrave Handbook of Learning and Teaching International Business and Management, 33–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20415-0_3 Li, M., Mobley, W. H., & Kelly, A. (2013). When Do Global Leaders Learn Best to Develop Cultural Intelligence? An Investigation of the Moderating Role of Experiential Learning Style. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 12(1), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2011.0014 Maarop, A. H., & Embi, M. A. (2016). Implementation of Blended Learning in Higher Learning Institutions: A Review of Literature. International Education Studies, 9(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v9n3p41 McKenna, K., Gupta, K., Kaiser, L., Lopes, T., & Zarestky, J. (2019). Blended Learning: Balancing the Best of Both Worlds for Adult Learners. Adult Learning, 31(4), 139– 149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045159519891997 Miettinen, R. (2000). The concept of experiential learning and John Dewey’s theory of reflective thought and action. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 19(1), 54– 72. https://doi.org/10.1080/026013700293458 Merriam, S. B. (2001). Andragogy and Self-Directed Learning: Pillars of Adult Learning Theory. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2001(89), 3. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.3 Passarelli, A. M., & Kolb, D. A. (2011). The Learning Way: Learning from Experience as the Path to Lifelong Learning and Development. The Oxford Handbook of Lifelong Learning, 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195390483.013.0028 Picciano, A. G. (2019). BLENDING WITH PURPOSE: THE MULTIMODAL MODEL. Online Learning, 13(1), 1–64. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v13i1.1673 Russell-Bennett, R., Rundle-Thiele, S. R., & Kuhn, K.-A. (2010). Engaging Marketing Students: Student Operated Businesses in a Simulated World. Journal of Marketing Education, 32(3), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475310377758 Schwartz, M. (2012). Best Practices in Experiential Learning. Ryerson University Teaching and Learning Office. Available at: http://ryerson.ca/content/dam/lt/resources/handouts/ExperientialLearningReport.pdf Seaman, J. (2007). Takingthingsinto account: learning as kinaesthetically-mediated collaboration. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 7(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670701349673 57 Serrano, D. R., Dea‐Ayuela, M. A., Gonzalez‐Burgos, E., Serrano‐Gil, A., & Lalatsa, A. (2019). Technology‐enhanced learning in higher education: How to enhance student engagement through blended learning. European Journal of Education, 54(2), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12330 Shea, P. (2007). Towards a conceptual framework for learning in blended environments. In Blended learning: Research perspectives, Edited by: Picciano, A. G. and Dziuban, C. D. 19–35. Needham, MA: Sloan Consortium. Shepherd, I., Leigh, E., & Davies, A. (2019). Revisiting the Impact of Education Philosophies and Theories in Experiential Learning. The Palgrave Handbook of Learning and Teaching International Business and Management, 9–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20415-0_2 Snowball, J. D. (2014). Using interactive content and online activities to accommodate diversity in a large first year class. Higher Education, 67(6), 823–838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9708-7 Swain, J., & Hammond, C. (2011). The motivations and outcomes of studying for parttime mature students in higher education. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 30(5), 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2011.579736 U.S. Department of Education. (2010, September). Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studies. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/tech/evidence-basedpractices/finalreport.pdf Vaughan, N. D. (2013). Teaching in Blended Learning Environments: Creating and Sustaining Communities of Inquiry (Issues in Distance Education) (Illustrated ed.). Athabasca University Press. World Health Organization. (2019a). WHO Learning Strategy: Literature Review Report. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/learning-strategy/1-full-litreview-learning-strategy-2019.pdf?sfvrsn=a1fafc5c_4 Yang, H. H., Zhu, S., & MacLeod, J. (2016). Collaborative Teaching Approaches: Extending Current Blended Learning Models. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41165-1_5 Youde, A. (2018). Andragogy in blended learning contexts: effective tutoring of adult learners studying part-time, vocationally relevant degrees at a distance. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 37(2), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2018.1450303 58 Appendix A Frame 1: Collected Research Data TEACHING TECHNIQUES (as deduced from theory) Business School Country Name of Blended MBA Program Case Studies Simulations Hands-On Experience (laboratory, workshop, onthe-job experiences, internships) Collaborative learning (peer-to-peer, group work, discussions, debates) HEC Paris, London Business School and New York Stern IESE Business School France/UK YES NO YES "Capstone Project is an opportunity to apply your program learning to your current business environment, a start-up or a social cause" YES YES ("Case Study Method: You will hone your critical thinking and decisionmaking capabilities by analyzing real-world business challenges and outlining a course of action among a pool of equally plausible solutions") YES ("Simulations and roleplays: Realistic test environments, complete with time constraints and opposing power sources, will advance your executive and communication skills") YES ("In Company Project - working in teams with a sponsoring company, you will identify a real-life challenge and build an actionable plan to address it") YES ("Peer-to-peer learning will expose you to new ideas and practices outside your sector and corporate sphere, as well as enhance your professional network") YES ("Engage with other global professionals in synchronous and asynchronous sessions including interactive small groups where you work on real-world, industrybased case studies") NO IE Business School Spain / US Spain Global Executive Trium Program in cooperation with London Business School and NYU Stern Global Executive MBA Global Online MBA ("You continuously explore business problems from an array of angles, exploring new approaches that translate into practicable solutions that you can apply immediately in your own work for direct and continuous impact") YES ("its advanced, multi-platform learning environment. Thanks to this unique approach, which combines interactive courses with practical, hands-on experiences, you can learn in the same way you work") ("Immediate impact - From day one, the Global Executive MBA delivers a curriculum that is as rigorous as it is relevant to your needs. The modular YES ESMT Berlin Germany Part-time MBA in Business Innovation (NEW - started in 2019) NO NO ESCP Business School France / UK / Germany / Spain / Italy / Poland Online Executive MBA NO NO Warwick Business School UK Distance Learning MBA YES YES ("You will work with your group online and take part in a WBS built simulation where you complete tasks as if solving real life company issues") format means you apply on-campus learning, new ideas and approaches in your day-to-day work immediately – putting theory into practice with real-time impact") NO YES ("Designed to provide participants with a collaborative, multidisciplinary and intercultural work experience on a real-life strategic challenge. The 12-month International Consultancy Project (ICP) puts into practice the concepts and theories acquired during the EMBA. Within a group, you will perform an in-depth analysis of a challenge faced by a company and make recommendations for actions that can be realistically implemented by the client firm") YES ("Your dissertation will allow you to apply what you have learned during your MBA to a real management issue in practice. You are required to source your own project, so this is often from your own organisation. However, if you are interested in changing either your functional role or the sector that you work in, you can use your dissertation as a stepping-stone to transition by working on sourcing a project for a different YES ("During each course, you benefit from the flexibility of interactive online learning at your own pace while also learning from your peers and world-class faculty both online and in person") YES ("As a participant of the programme, you will share your experience with a multicultural group of peers, both in terms of nationalities and professional backgrounds. This international perspective is an invaluable asset in today’s global environment") ("Within a group, you will perform an in-depth analysis of a challenge faced by a company and make recommendations for actions that can be realistically implemented by the client firm") YES ("For assessed group work, you will work in teams to investigate an aspect of a module in the real-world and co-create an assessed piece of work on the day") ("As part of a close-knit cohort, you will have the opportunity to build your professional network with experienced colleagues from a selected range of industries and functional backgrounds. Your learning 60 organization or within a new functional area") Imperial College Business School WHU – Otto Beisheim School of Management Henley Business School UK Germany UK Executive MBA Global Online MBA (NEW 2020) Flexible Executive MBA YES (application of "knowledge to real-world case studies") YES ("Engage in real-life case studies and gain new tools to help propel your career and drive change in your chosen industry") YES YES ("With essential performance feedback from the simulator, we’re able to target and train advanced communication techniques to refine visible authenticity in your leadership skillset") YES ("Studying and working simultaneously means that you will immediately apply your learnings to your organisation”) NO NO experience does not end in the lecture theatre, as you’ll participate in case studies, group work, assessment briefings, networking, careers and study skills sessions.") YES ("These modules are all assessed by group projects and you will find yourself working alongside a culturally rich group of exceptional individuals from numerous industries") The collaborative, discussionbased format of our classes stimulates networking and idea sharing that will have a direct impact on your business") YES ("gain global business insights through active dialogue with a diverse group of peers") ("thrive in a collaborative group setting, where new ideas come to life") NO YES In-company project ("Study alongside global peers with a mixture of live interactive classes and asynchronous sessions, led by an international faculty and business experts") YES ("The course is structured to allow you to continue to work full-time and study your MBA part time, connecting your learning to current and relevant organisational issues. Our MBA programmes combine the best in academic theory 61 Alliance Manchester Business School Durham University Business School Politecnico di Milano School of Management UK Global Part-Time MBA; YES ("Work in groups to apply theory to case studies based on real business problems") UK Blended / Online MBA YES YES ("Test yourself with a simulation project based on global business and management challenges. The simulation project will challenge you to rigorously analyse and overcome business problems. You will apply knowledge and skills from different areas of business and management, experience the interdependencies in decision making in an organisation, explore the dynamics of working in multicultural groups with colleagues from diverse professional backgrounds") NO Italy International Flex Executive MBA YES YES with practical, real life projects. This means that as well as having an outstanding learning experience, you will be ready to put it all into practice immediately when you are back in the workplace") YES ("Shape your experience by exploring a business challenge in your own organisation, or an entrepreneurial opportunity in a sector of your choice. A supervisor provides support and feedback at all stages. The project is a great chance to: Test your next career move in a live business environment, or gain experience in a new sector, Explore trends and opportunities for innovation, Apply the knowledge you have acquired to solve a real business problem") YES ("you continue in full-time employment, so you can apply what you learn directly into the organisation you work for") YES ("Put the theory and the skills you are learning into practice through Management Bootcamps") YES ("Explore the dynamics of working in multicultural groups with colleagues from diverse professional backgrounds") YES YES ("Gain and share knowledge within an international community of companies and students") ("real business innovation or entrepreneurial development project, in which the concepts learned in the Master can be applied to a concrete 62 Hult Ashridge Executive Education Maastricht University School of Business and Economics OVERALL: UK The Netherlands Live-Online MBA Online EuroMBA NO NO NO NO Case Studies: 11 / 14 Simulations: 5 / 14 business case. In fact, the Business Transformation Project represents an excellent opportunity to realise consulting projects in your company or to develop a new business idea") YES ("We collaborate with leading companies and entrepreneurs to challenge you to tackle real-world problems throughout your program") ("MBA that enables you to immediately apply what you learn to your daily working life. Increase your skills and your career options without taking time out of your current job; Hult’s Live Online MBA ensures you are best placed to lead in this reality as you learn by doing.") YES ("Business consulting project - at the end of your MBA you will translate your learnings into a final project that addresses a real and current management problem in your organisation") Hands-on Experience: 12 / 14 YES YES ("The online study platform enables intensive interaction with your peer students. Via this platform, you can collaborate 24/7 on projects and exchange experiences. During the three residential weeks, you will meet your fellow students face to face") Collaborative Learning: 14 / 14 63 Appendix B Frame 2: Collected Research Data ELEMENTS OF FLEXIBILITY (as deduced from theory) Business School Country Name of Blended MBA Program Time (program length overall, flexibility in face-to-face, flexibility in online) Place (flexibility in face-to-face, flexibility in online) Path (flexibility in choosing electives, flexibility in choosing the order of courses or workshops) HEC Paris, London Business School and New York Stern France/UK Global Executive Trium Program in cooperation with London Business School and NYU Stern Program Length: NO - one option only - 18 months Face-to-Face: NO NO Face-to-face part: NO Online: YES - for all aspects of online learning IESE Business School Spain / US Global Executive MBA Online part: YES - for all asynchronous aspects of learning 6 modules - 18 months Face-to-face: 10 weeks Online: 15.5 months Weekly time investment: 15-20 hours Each module one face-toface event with duration as follows 2 weeks + 2 weeks + 2 weeks + 1.5 + 1.5 weeks + 1 week + 1 weekend) Program Length: NO, one option only - 16 months Face-to-Face: NO Face-to-face part: NO Online: YES - for all aspects of online learning YES Two 4-week On-campus electives selected out of 6 offered Online part: YES - in all asynchronous aspects IE Business School Spain Global Online MBA 6 core modules - 16 months Face-to-face: 12 weeks Online: 36 weeks Each module: 2-week ONLINE PREPARATION 2-week ON CAMPUS - 4-week ONLINE CONSOLIDATION Program Length: YES - two tracks possible 17 or 24 months Face-to-face: NO Online: YES Optional 7-month online semester (added to the YES The Capstone Project allows students to choose entrepreneurship or 64 final period of program) intrarpreneurship track; Face-to-Face: NO During third period students select six electives out of an array of available choices Online: YES - except for the two 2-hour live video conferencing sessions weekly 3 mandatory plus 1 optional period: 17 or 24 months in total Face-to-face: 3 weeks total Online: rest Pre-program: 3 week online preparation First period: 6 months starting with 1-week face-toface Second period: 5 months starting with 1-week face-to-face Third period: 6 months ending with 1-week face-toface Fourth period (OPTIONAL): 7-month online module ("During each course, you benefit from the flexibility of interactive online learning at your own pace while also learning from your peers and world-class faculty both online and in person") 65 ESMT Berlin Germany Part-time MBA in Business Innovation (NEW - started in 2019) Program length: NO - 24 months the only option Face-to-face: NO Face-to-face: NO YES Optional week-long module abroad Online: YES Online: YES - for all synchronous sessions ESCP Business School France / UK / Germany / Spain / Italy / Poland Online Executive MBA 80% online - 20% face-to-face Face-to-face: takes place during 14 weekends Weekly time investment: 12-15 hours without faceto-face Program length: YES - 3 track options - 18, 22, or 30 months Face-to-Face: NO Online: YES, except for live conferencing sessions Warwick Business School UK Distance Learning MBA Face-to-face: YES Ability to choose from 5 different campuses worldwide to attend electives workshops YES 10-12 mandatory elective courses, 2 optional elective courses (each equivalent of 12 contact hours) selected out of over 50 offered options Three tracks: 18, 22, or 30 months 5 week-long face-to-face workshops/seminars 9 core modules: 7 fully remote and 2 onsite 520 hours of live teaching regardless of format Online: YES 9 core modules can lead to completion of GMP degree (General Management Program); once remaining courses are complete it leads to Executive MBA degree Program length: YES - 24 to 48 months ("we’ve built the Distance Learning MBA with flexibility in mind. This means that when your job needs to take precedence for a while you can choose to slow down or take a break of up to two years before continuing your studies. You may complete your Distance Learning MBA in two to four years depending on your personal circumstances") Face-to-face: NO YES Selection of mandatory electives Online: YES Optional elective 1 optional face-to-face (4-5 days) elective module included Optional residency Face-to-Face: NO Fixed format of 2 residential mandatory weeks 66 1 optional face-to-face (4-5 days) elective module included Online: YES All live sessions are recorded for later asynchronous viewing Imperial College Business School UK Executive MBA 8 mandatory modules (each approximately 100 hours, of which 27 hours of live teaching and online learning) - rest is guided structured selfstudy 4 mandatory electives taken online or onsite (up to two can be taken onsite) Dissertation Program Length: NO - 23 months Face-to-Face: YES for elective modules since they can also be taken online or with different face-toface options (weekends or during the week) Online: YES - all asynchronous part of the program The content is accessible at any time Face-to-face: YES Ability to follow face-toface activities online for on-campus classes per core module Online: YES YES 5 mandatory electives selected out of 35 with two more optional non-assessed electives("Electives are offered in four formats to fit your schedule") 3-day residency in Germany (manufacturing German Way) and 1-week residency in China (Doing Business in China)Online preparation week Onsite induction week Year 1: 8 core modulesYear 2: electives, Final Project, European Study Tour, International Residency Face-to-face: approximately once a month in the first year 13 face-to-face weekends with the first and last weekend lasting 4 days 67 WHU – Otto Beisheim School of Management Germany Global Online MBA (NEW - 2020) Program length: YES - 18, 36 or 60 months Face-to-face: NO Face-to-Face: NO Online: YES Online: YES - except for weekly live sessions Live-teaching sessions once a week for 60 – 120 minutes One 5-day mandatory workshop (midterm challenge) Students are able to choose an optional module abroad over the course of one week - US, China, or Germany 18 months fast track, workload 18.5 hours per week 36 months flexible track, workload 9.25 hours Certificate option to finalize Global Online MBA over a course of five years Henley Business School UK Flexible Executive MBA Program length: NO, fixed 30 months Face-to-face: NO Face-to-Face: NO, unspecified Online: YES Online: YES Alliance Manchester Business School UK Global Part-Time MBA; Workshops held every two months Program length: YES - 18 (accelerated) or 24 months (normal) Face-to-Face: YES for electives Elective workshops can be longer than standard Most courses include an intensive three-day workshop residential Online: YES - except for the weekly live session Face-to-face: 17 days in first year and 13 days in year 2 YES Option to choose optional module abroad ("Personalize your studies by selecting elective courses relevant to your interests and participate in an optional faceto-face module abroad to discover new markets") Face-to-face: YES Workshops for elective courses can be attended at any of Manchester global centers: Dubai, Hong Kong, Manchester, São Paulo, Shanghai and Singapore. Additional locations are also possible. YES ("There are a range of elective modules to allow you to specialize, as well as an applied business or incompany project and international study visit") YES Option to choose 3 out of 20+ offered electives Possibility to also study an additional complimentary elective with a workshop at any of our global locations. Option to change location of studies without interruption at any of Manchester centers in case of relocation 68 Possibility to also study an additional complimentary elective with a workshop at any of our global locations. Elective workshops can be online or onsite Durham University Business School UK Blended / Online MBA Program length: NO - fixed 24 months Face-to-face: NO Online: YES - except for live webinar sessions, Access to learning content 24/7 Weekly time investment: 15 hours Online: YES Face-to-face: YES Ability to choose either fully online or blended approach Online: YES YES Three pathway options, entrepreneurship, consultancy or technology Ability to choose optional electives ("Flexibility is at the heart of the Durham MBA, as you have the choice to study entirely online or take a blended approach, combining online learning with residential modules. You can also personalise your programme by completing a Pathway choosing a combination of optional modules which align with your career ambitions and goals")("Pathway in either entrepreneurship, consultancy or technology. Each Pathway includes two academic modules, skills workshops and strategic insights provided by industry experts. The Pathways provide an excellent 69 Politecnico di Milano School of Management Italy International Flex Executive MBA Program length: YES 20 months as a standard, but students can spread the work in the way they think fit, according to their personal needs; possibility of customizing the duration of the Final Project. There are two alternatives thus also making the actual duration of the course totally customizable. Face-to-face: YES For electives Online: YES Face-to-face: NO Online: YES Learning content is accessible from wherever, whenever and with a device using any of the main operating systems Hult Ashridge Executive Education UK Live-Online MBA Program Length: YES - 18, 24 or 36 months ("You can accelerate your degree by taking more electives over the summer, or spread them out over more summers if you need a more relaxed pace") Face-to-Face: NO At the start of the program, week-long face-to-face leadership immersion at Boston, London or Dubai campus (also online possible) Online: YES All activities except for monthly live lecturing are asynchronous Face-to-face: YES Face-to-face elective workshops take place at any of the six campuses of the program All onsite activities can also be conducted online First week onsite workshop can also be conducted online Online: YES Online live sessions over a four-day weekend each month in either Boston, London, or Dubai time zones, taught by expert practitioner-professors opportunity for you to develop your knowledge, skills and capabilities in a specific area most suited to your own professional needs") YES In the fourth part of the program students can customize their EMBA by choosing between two paths, innovation or digital transformation A third face-to-face week is elective, and student can choose among a Management Bootcamp, an Elective Course of the Executive MBA, a Doing Business In China or Mexico or a Study Tour in Silicon Valley; YES Degree can be personalized with a wide range of electives and seminars offered in both 3day weekend and longer formats at Hult campus locations across the globe. Optional multi-day leadership immersion also available at Boston, London or Dubai campus. Full range of electives are available face-to-face at campuses in Boston, San Francisco, London, Dubai, Shanghai, and New York for 70 Maastricht University School of Business and Econo The Netherlands Online EuroMBA Initial face to face week at the start of the program additional fee. 24-month is normal track; 18 months to 36 months is possible Alternatively, you can choose from a range of online electives and continue to study from home without additional fee. YES "Our flexible modular online courses allow you to complete the programme in any order you like. With our online learning environment, you study where and when you want. This is the ideal solution for ambitious professionals who sometimes need to prioritize work over study. For each online course that comes along, simply choose whether you will join it or not. As long as you complete all online courses and residential weeks within four years, you are free to organize your study as you wish" Program Length: YES - 24 to 48 months Face-to-face: NO Face-to-Face: NO Online: YES ("Our flexible modular online courses allow you to complete the programme in any order you like. With our online learning environment, you study where and when you want. This is the ideal solution for ambitious professionals who sometimes need to prioritize work over study. For each online course that comes along, simply choose whether you will join it or not. ") Except for the first residential week, the rest of the program can be taken flexibly, in order and time as suitable for the student Online: YES - except for the live webinars. Online courses in general can be taken flexibly as suitable to the students and are offered at 2 year cycles; the online learning platform also allows for 24/7 collaboration with your peers from anywhere and at any time Maastricht residential week - 5 days (42 hours); OVERALL: Time: Program Length: 8 / 14; Online: 14 / 14 Face-to-Face: 2 / 14 Place: Face-to-face: 6 / 14 Online: 14 / 14 Path: 12 / 14 71 Appendix C List of Sources Used for Data Collection 1. HEC Paris, France; London School of Business, UK; New York Stern, US Global Executive Trium Program https://www.triumemba.org/ 2. IESE Business School, Spain Global Executive MBA https://globalexecutivemba.iese.edu/ 3. IE Business School, Spain Global Online MBA https://www.ie.edu/business-school/programs/mba/global-online-mba/ 4. ESMT, Berlin, Germany Part-time MBA in Business Innovation (NEW - started in 2019) https://degrees.esmt.berlin/part-time-mba 5. ESCP Business School, France / UK / Germany / Spain / Italy / Poland Online Executive MBA https://escp.eu/programmes/online-executive-mba 6. Warwick Business School, UK Distance Learning MBA https://www.wbs.ac.uk/courses/mba/distancelearning/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA_qD_BRDiARIsANjZ2LAYPa5Ku5Y2SjlFPtWj3Evd8y B_JksR_C6AOGqql7yVI9hgEWgVAIAaAh-6EALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds 7. Imperial College Business School Executive MBA https://www.imperial.ac.uk/business-school/programmes/executive-mba/ 8. WHU Otto Beisheim School of Management, Germany Global Online MBA (NEW - 2020) https://www.whu.edu/programs/global-online-mba/ 9. Henley Business School, UK Flexible Executive MBA https://www.henley.ac.uk/study/mba/flexible-executive-mba 10. Alliance Manchester Business School Global Part-Time MBA https://www.alliancembs.manchester.ac.uk/study/mba/global-part-time/ 11. Durham University Business School Blended / Online MBA https://www.dur.ac.uk/business/programmes/mba/online-mba/ 12. Politecnico di Milano School of Management International Flex Executive MBA https://www.som.polimi.it/en/course/mba/the-international-flex-executive-mba/ 13. Hult Ashridge Business School Live-Online MBA https://www.hult.edu/en/programs/live-online-mba/ 14. Maastricht University School of Business and Economics Online EuroMBA https://maastrichtmba.com/euromba-online/ 73 Declaration of authorship of an academic paper I hereby declare that I have written this paper myself and used no other sources or resources than those indicated, have clearly marked verbatim quotations as such, and clearly indicated the source of all paraphrased references, and have observed the General Study and Examination Regulations of Reutlingen University for bachelor and master programmes, the specific regulations for study and examinations of my study programme, and the Regulations for Ensuring Good Academic Practice of Reutlingen University. Neither this paper nor any part of this paper is a part of any other material presented for examination at this or any other institution. Reutlingen, 30.12.2020 Signature Eldar Husanovic 74