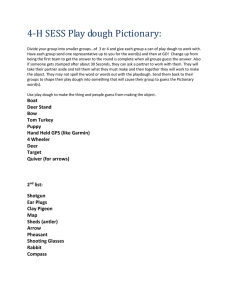

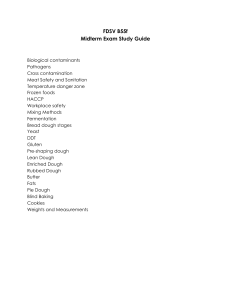

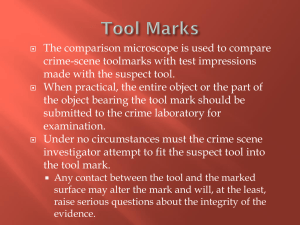

Impression Obsession Exploring science phenomena in a play-centered preschool classroom By Jane Tingle Broderick, Kathryn Boniol, Nathan Martin, Kate Robshaw, and Virginia Holley E arly experiences with planning and guiding children’s learning are exciting for preservice teachers in undergraduate teacher training programs. In this article, observations of a preschool play session guide four preservice teachers to design a series of play-centered lessons addressing serious science concepts (Hall 2010). While the concepts guided in these lessons are not new, identifying science thinking in children’s play is valuable for preservice and inservice teachers as they plan learning opportunities that extend children’s knowledge. This can be done by providing materials over long periods of time and using an engage, explore, reflect process, checking for understanding and relying on observations to guide long-term inquiry (Chalufour 2010). The ways these preservice teachers used observations of play and research questions to shift children’s focus on the tracks of dinosaurs in play dough to a more general look at the physical science phenomena of pressure and force (Duckworth 2006) are discussed here in the voice of the preservice teachers. The assignment guiding this process asked preservice teachers to observe play, record their observations, then meet together to discuss and write their interpretations of the children’s thinking. They were to use their interpretations to develop questions to plan for and guide a next play session. The complete assignment required the implementation of three sessions with children. OBSERVATIONS LEAD TO SCIENCE EXPERIENCE On a crisp, clear day in a children’s center in east Tennessee, four fouryear-old children were making im- FIGURE 1 PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE AUTHORS Setup of first science experience. 76 • • JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2021 pressions of familiar objects in play dough. Children chose the learning centers where we first observed their play. It was in the kitchen center where we noticed some children were making stepping motions with plastic dinosaurs in play dough and observing the resulting footprints. This subtle activity caught the observers’ attention. It led to planning a session that included various objects with materials in which these objects can make impressions. Our initial focus included a consideration of weight but quickly shifted based on our observations of children’s thinking that went in other directions, such as the impact of pressure and time on impressions. DESIGNING A SCIENCE LESSON When planning for play-based learning experiences, a goal is to set up the materials in a way that invites children to spontaneously enter and explore. Children naturally learn through play experiences that challenge their intellect (Duckworth 2006). Formulating research questions based on the play we’d observed was our strategy for designing a lesson plan that embeds inquiry into a welcoming setting that feels like play to the children. Three questions guided our planning process: • How does the medium affect the impression? • What does size say about weight? • What affects impressions besides size? The lesson plan was to provide toy dinosaurs, along with a variety of other available items, to help the children learn about the effect of size on the impression. Teachers can search through their school and homes to discover items for testing the effect of object size on impressions like the simple hardware (sockets, rocks, and marbles) we located for their similarity of size. It was also important to include toy dinosaurs in this plan, as a way to intentionally link the new experience to children’s previous play. The idea was to challenge children’s ideas that an object of a similar size might have a different impact when creating an impression. Clay, play dough, and sand were provided as surfaces for making impressions. They were presented to children in flat bases of plastic containers or flattened on a table surface. The toy dinosaurs, sockets, rocks and a big marble were arranged in categories (see Figure 1). Children were invited to interact with the materials to observe the different types of impressions made by each of the objects, noticing and comparing impressions in sand, play dough, and clay. Additionally, safety precautions were in place in that materials were developmentally appropriate, were chosen with consideration of the guidelines for safe materials at the preschool, and were identified as nonhazardous (NAEYC 2009); according to the NSTA guidelines for safety, children were supervised throughout. Children were delighted with this play invitation. They engaged deeply for a long period of time observing differences in the impacts of objects in play dough. There were several experiments we observed. Many children were comparing the impressions of two different objects in the play dough. “Ethan puts a different dinosaur into the play dough and contemplates the differences between the two impressions that he made with the dinosaurs in the playdough.” Other chil- dren were holding objects for different lengths of time to notice the effect of time and pressure on the imprint. “Wait five minutes. You need to wait for it to make a square.” This child and others were curious about the relationship of the shape of an object and the shape of its impression. Some children noticed the relationship of the physical nature of objects to things with which they are familiar, like a socket with a hole looking like a telescope (see Figure 2). Our observation records state that “Billy was observing the difference of pressing a rock into the clay with a hard versus a soft force.” Through testing of clay, play dough, and sand, children noticed that sand was not a good material for creating substantial impressions. EXTENDING THE LESSON Time with materials allows children to find their own approach to experimentation. Very young children and preschoolers may engage with materials for lengths of time without much verbal conversation because their actions are their focus. This sort of silence and attention is a good sign of a deep motivation that guided us to plan for a next-day lesson that included similar materials with some slight tweaking in the presentation as a strategy to capture children’s interests while inviting continued experimentation. A goal F IGURE 2 Exploring force and shapes. www.nsta.org/science-and-children • 77 FIG U RE 3 Interpretation of previous play session. Social Distancing Experiences with impressions can be adapted to the new virtual learning opportunities that early childhood teachers are designing during this time of COVID-19. A few steps can assist children and families at home to be successful. Each can be provided as individual activities on different days. 1. Provide families with this recipe for making playdough or this video where a mother and her young children show how to make playdough (see Internet Resources). a. Teachers can gather a variety of items for making impressions from around their home. Consider items that might be found in the homes of children. Then, using a phone, videotape yourself rolling out playdough into slabs and experimenting with making impressions in the playdough. Talk aloud as you experiment to help children learn about the sorts of things you are noticing, for example, “I see the texture of the pinecone,” or “I see the shape of this bottle cap.” 2. Send the video to families with a written invitation to a. View the video. b. Hunt for items in their homes that they can use to make impressions in playdough. c. Experiment with the objects making impressions. d. Tell their family members the details they are noticing. e. Ask a family member to document what children do and say with video or photos while also writing what the children observe and discover. 3. Ask children and families to share their discoveries in a virtual class meeting where family photos can be shared as children describe their processes, or family videos can be shared to reveal discoveries. Allow for more than one class meeting for sharing if there is interest to extend the explorations. Teachers can use questions from the article as prompts for the virtual discussions. 78 • • JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2021 is for children to encounter materials from previous play so they can incorporate ideas and thinking that may make play feel seamless from one day to the next. Reviewing our observation records led to interpretations (see Figure 3) and possible research questions we could form around the interactions with materials we observed and assisted us in determining the types of materials to include and to add to extend children’s thinking. We realized children were able to understand the concept that objects can create different markings in the play dough, that the depth of an impression relates to the force of their applied pressure, that there is a relationship of the shape of the object to the shape of the impression, and a relationship between the time one applies pressure to an object and the impression it makes. We also shifted our questioning and planning thinking to accommodate these experiences. The materials for our extended science experience included play dough, play dough tools, blocks, bottle caps, big caps, pennies, tiny puzzle pieces, leaves, shells, and rocks of different sizes. The objects were lined along the edge of the table, carefully organized into the categories of natural and humanmade. The beauty and aesthetics of the setup was intentionally designed to excite the children and gain their attention (see Figure 4). The following research questions guided our planning and were used with children as invitations to explore. • What kinds of shapes can you make with these objects? • Look and see how deep you can make your impressions. • What is the relationship between length of time of pressure and the imprint of the object? Children immediately began to experiment with making impressions in the FI G URE 4 Setup of second science experience. several slabs of play dough that were rolled flat and ready for play. They began to think about the possibilities for the many different kinds of impressions and shapes these objects might make. Repetitive imprints using the same object led to the development of patterns. Nicole demonstrates understanding of the correlation between the impressions of objects of the same shape but of different sizes when making an impression with a bottle cap. She says, “It’s a circle.” She went on to make an impression with a larger cap when prompted to look for other objects that can make a circle impression (see Figure 5). We were intrigued by children’s sensitivity to the details of their impressions, like the veins of a leaf or the texture and image formed from a block of wood. An example from our observation records state that, “Molly makes a pressing with a leaf and feels the impression it left behind. Molly then does the same with a penny. Molly uses more force to push a penny F IGURE 6 Molly’s impression made with her sleeve and Nicole manipulating the size of the play dough. F I G URE 5 Circles of different sizes. www.nsta.org/science-and-children • 79 into the play dough.” Her remarks also indicate that she was able to recognize that the amount of pressure placed on an object directly impacts the depth of the impression. “This circle is so deep! It’s a face. It’s a mommy.” The simple research questions we planned as invitations to guide this experience prompted further thinking and learning (Duckworth 2006) but did not prevent the children from following their own new interests, like texture, as they explored phenomena of the depth, pressure, and shape of impressions. A THIRD EXTENSION Through examining the interests of the children (Chalufour 2010; Hall 2010) in the previous play session, we decided to once again include the same wide array of tools, with the categories of manmade and natural materials and flattened play dough. The children’s continued focus was evidence that they had not exhausted their ideas for experimentation with these materials. Our intention was for the children to continue exploring the phenomena of shape and force as they created impressions and textures. We had also saved some of the impressions from the previous session to include with the setup as inspirational guides. We relied on the research questions from the previous day to guide this lesson extension and included a new research question based on the potential for children to create and recognize patterns as they experiment with the materials: Could some of these objects be used to make patterns? The variety of objects continued to spark interest in exploring the intended phenomena, but so did some unexpected tools, like children’s clothing. Molly noticed that the sleeve of her shirt left an imprint and excitedly repeated the process by pressing her sleeve into the play dough. She was learning that impressions can be made unintentionally and then recreated. Nicole discovered how the force used to manipulate a rolling tool can affect the dimensions of the play dough, making a smaller slab into a F IG URE 7 Nicole’s shell impression. larger one. “It’s rolling. It gets bigger” (see Figure 6). There were many ways we observed children demonstrating their understanding of the basic concept of an impression, which was one underlying factor guiding each play session. Children were learning that patterns in the impression matched the pattern of the object applying the pressure. For example, we observed Nicole turning over a shell, rubbing her finger along the ridges of its underside and then rubbing them over the ridges in the shell’s imprint in the play dough (see Figure 7). Ethan said, “It makes dough with spots,” when he noticed the pattern in the play dough matched the pattern in the rolling pin Nicole was using. Children were experimenting with the idea that patterns are repeatable, like the creation of a row of impressions of small bricks, circular sockets, or pennies. Ethan found that pressure can force a hole through a slab of play dough, and Molly liked the quality of creating a textured impression of one object (brick) on top of the impression of another object (leaf). Children were designing their own experiments with a variety of patterns, like the use of various scraps of wood and blocks to make rectangular and square shapes onto the surface of one slab of play dough (see Figure 8). At the close of our third day with children, we learned that we can make simple changes to the materials and their arrangements, and form new perspectives for exploring the materials by reviewing our observations of children’s play. While it was our last day for our field experience as preservice students, the mentor teacher recognized the potential for maintaining the learning center we had designed and continuing to develop extensions over time. CONCLUSION The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC 80 • • JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2021 2009) advocates play-based curriculum as the best tool for facilitating learning with young children. This type of curriculum can initiate higher order thinking skills and extend the potential for learning. Through the play-based experiences, students were able to meet many of the Tennessee Early Learning and Development Standards (TN–ELDS) in the following domains: sensorimotor, fine motor, geometry, social emotional relationship, and science. Originally, we began our work with the intent of exploring size through experimental play with selected materials. Throughout our lessons, we held an intentional focus of the effects of different objects on the impressions they can make in a malleable material like play dough. We remained flexible with our planning in relation to the thinking we observed that included the impact of shape and force on impressions. As preservice teachers, we learned that it is possible to approach simple activities like manipulation of play dough as serious endeavors for developing science curriculum that can engage children intellectually over the course of many play sessions. We learned that an open-ended approach allows children to explore phenomena like shape and force in ways that encourage them to discover many other concepts that include repeatable patterns, creating textures, and the use of tools to alter the shape and size of a slab of play dough. Developing research questions to guide the play, like, “how does shape, or time or force affect an impression?” helped us guide children’s understanding of the processes that were engaging their minds (Duckworth 2006). As professionals, teachers can engage children in conversations where teachers incorporate science terminology and questioning to help children solidify the concepts that they are learning through play (Duckworth 2006). For example, introduc- ing terms like pattern, deep, and pressure, give meaning to the children’s actions and provide language they can continue to use. Observations were our ongoing formative assessments for evaluating the effectiveness of our previous lessons and deciding how to add new thinking and depth into the extended lessons. We paid attention to children’s actions and words using running records to capture verbatim accounts. We revisited these records after each lesson to interpret and gain insight into children’s purposes and what they might be questioning. For example, the nonverbal process of pushing the penny into the play dough with less or more pressure demonstrated that children were exploring and questioning force. Using play and children’s interests as the basis for our planning, we saw the potential for endless possibilities within and beyond our lessons, and we were able to maintain children’s engagement. Time is an essential factor in an approach like ours, where very subtle shifts in materials can allow children more time to experiment and perhaps repeat previous experiments to deepen their understanding of the phenomena they encounter with particular materials. ● F IGURE 8 A variety of experiments with pattern, force, and shape. www.nsta.org/science-and-children • 81 REFERENCES Childhood Research & Practice 12 (2): Fall. Retrieved from: https:// ecrp.illinois.edu/beyond/seed/hall. html NAEYC. 2009. Developmentally Appropriate Practice in early Childhood Programs Serving Children Birth through Age 8: A Position Statement of the National Association for the Education of Young Children. Retrieved from: https://www.naeyc.org/sites/ default/files/globally-shared/ downloads/PDFs/resources/ position-statements/PSDAP.pdf Chalufour, I. 2010. Learning to teach science: Strategies that support teacher practice. Early Childhood Research & Practice 12 (2): Fall. Retrieved from: https://ecrp.illinois. edu/beyond/seed/chalufour.html Duckworth, E. 2006. The Having of Wonderful Ideas: And Other Essays on Teaching and Learning. New York: Teachers College Press. Hall, E. 2010. What professional development in early childhood science will meet the requirements of practicing teachers? Early NGSS Lead States. 2013. Next Generation Science Standards: For states, by states. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. www.nextgenscience.org/nextgeneration-science-standards. INTERNET RESOURCES Best homemade playdough recipe https://www.iheartnaptime.net/playdough-recipe/ How to Make Playdough Homemade DIY with Ryan’s World! https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=u8fS-lZmErw Jane Tingle Broderick (broderic@mail.etsu.edu) is a professor of early childhood education at East Tennessee State University in Johnson City, Tennessee. Kathryn Boniol is a graduate student in the Department of Early Childhood Education at East Tennessee State University. Nathan Martin is a preschool teacher in McEwen, Tennessee. Kate Robshaw is an undergraduate student in the Department of Early Childhood Education at East Tennessee State University. Virginia Holley is a graduate student in the Department of Early Childhood Education at East Tennessee State University. half PAGE JOURNAL NSTA Career Center 3 Simple Steps 1 POST to Find Qualified Science Teaching Professionals It’s really that simple… Visit the NSTA • INTERVIEW 3 HIRE The NSTA Career Center is the premier online career resource connecting employer to talented science teaching professionals. Post your jobs and tap into a concentrated talent pool of professionals at a fraction of the cost of commercial boards. Career Center to learn more http://careers.nsta.org 82 2 • JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2021 Copyright of Science & Children is the property of National Science Teachers Association and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.