Choix du Thème et Progression

Thématique dans le 'Extended

Essay' du Baccalauréat

International

Tome 1

(de 2 tomes)

Mémoire de deuxième année de Master Recherche

Lettres, Langues & Cultures Étrangères

Aire Culturelle du Monde Anglophone

Présenté à l’Université Aix-Marseille

Par monsieur Paul White

Sous la direction de madame Linda Pillière

Session septembre 2015

Abstract

The aim of this research project was to analyse 26 examples of the International Baccalaureate's

(IB) Extended Essay in History according to North's (2005) categorisation of orienting Themes

(textual, interpersonal and experiential) and topical Themes as well as McCabe's (1999) realisations

of thematic progression, in particular the simple linear progression and constant progression

structures.

Many studies have found correlations between Theme choice, particularly use of circumstantial

Themes, and thematic progression, particularly the use of simple linear progression and constant

progression, and a writer's first language, their level of proficiency in English, and also disciplinary

variation. Other studies have focused on the pedagogical possibilities surrounding teaching

students, especially non-native English learners, how to use Theme in their academic writing. The

basic hypothesis of the present study was that the successful use of Theme choice and thematic

progression correlates to the subject grades received by IB students.

The corpus consists of 26 extracts of 25 t-units (clause complexes) each, all written for the History

Extended Essay, which received subject grades ranging from A to E. The texts were sourced from a

international secondary school in the South of France, and also from the IB's publications '50

Excellent Extended Essays and 50 more Excellent Extended Essays' (2011). None of the

participants had received any kind of instruction regarding how to use different Themes and

thematic progression in their texts. Regarding Theme choice, the analyses carried out focused on

correlating the use of all orienting Themes, textual Themes, interpersonal Themes and experiential

Themes with subject grades. In relation to thematic progression, the analyses undertaken searched

for correlations between the use of simple linear progression, constant progression, and the ratio of

simple linear progression to constant progression with subject grades.

Positive, statistically-significant correlations were identified between the use of all orienting

Themes and subject grades, and the use of simple linear progression and subject grades. Where no

statistically-significant correlations were first identified, further research uncovered correlations for

some sub-categories. For example, although the use of experiential Themes did not correlate with

subject grades, the use of long experiential Themes (consisting of 10 words or more) was found to

be significant. The occurrence of these long experiential Themes often coincided with the use of

the simple linear progression, which in providing local cohesion allowed the writer to use the

topical Theme either to present new information without compromising cohesion, or to provide an

extra level of cohesion through the use of constant progression. As for the analysis of constant

progression itself and subject grades, although no correlation was found, a sub-category which I

define as 'inference constant progression' did correlate with subject grades. The essence of this subcategory is that it involved Themes linking back to previous Themes not through simple repetition

of the same words, or through substitution of a previous Theme with a pronoun, but instead used

synonyms, possessive adjectives, semantically-related words, and rephrasing to connect one Theme

to a previous one. This allows a writer to expand their use of vocabulary at the same time as

creating tight cohesive links through subtle shifts in the focus of the argument between t-units

referring to the same subject. Finally, although no correlation was found between the ratio of

simple linear progression to constant progression and subject grades (see Soleymanzadeh and

Gholami, 2014), some observations about the complex interaction of the use of orienting and topical

Themes, together with the use of new Themes, simple linear progression and constant progression

were highlighted. The main points to emphasize are that both elements which promote cohesion

like simple linear progression and constant progression, and those involved in breaks in cohesion

like new Themes, work together in the orienting and topical Theme positions to create complex

arrangements in highly-cohesive texts. I therefore argue that analysis of cohesion in academic

writing needs to go beyond fixations on correlations of global categories (like simple linear

progression or circumstantial Themes and cohesion) and instead look for both sub-categories of

these functions as well as interaction patterns between all these elements, whether taken

individually they are considered to assist in cohesion or not.

Finally, it is hypothesized that further research into the use of cohesion in the Extended Essay could

lead to the production of pedagogical materials which could help the tens of thousands of students

around the world who must write an Extended Essay as part of their IB qualification each year.

The referencing system used in this dissertation is the Harvard system (see

http://guides.is.uwa.edu.au/harvard)

Key words: Functional grammar, Orienting Themes, Topical Themes, Thematic Progression.

Contents

1. What is Theme?

1.1 The Origins of and Controversy surrounding Theme

1

1.1.1 The Historical Origins of Theme

1

1.1.2 Theme as content topic

1

1.1.3 Theme as Given/Known

3

1.1.4 Theme/Rheme in Communicative Dynamism

4

1.1.5 Theme as initial position

5

1.1.6 Theme as message onset

5

1.2 Halliday's operationalisation of Theme

6

1.3 An alternative operationalisation of Theme

10

1.4 Topical Themes

11

1.5 Thematic progression

12

2. Studies in the use of Theme in academic writing

2.1 Theme and Thematic progression and cohesion in learner English writing

15

2.2 Language background and Theme use

16

2.3 Proficiency level and Theme use

17

2.4 Disciplinary differences in the use of Themes

17

2.5 Instruction in the use of Theme and textual cohesion

19

3. Corpus and procedure

3.1 The corpus

22

3.2 Analytical framework

3.2.1 T-units as the unit of analysis

26

3.2.2 Orienting Themes identified

27

3.2.3 Which types of TP counted

32

3.2.4 Hypotheses

38

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1 Orienting Themes

4.1.1 Total orienting Themes

40

4.1.2 Textual Themes

42

4.1.3 Interpersonal Themes

43

4.1.4 Experiential Themes

45

4.2 Thematic Progression

4.2.1 Simple linear progression

49

4.2.2 Constant progression

53

4.2.3 Ratio of Simple linear progression to constant progression

58

4.3 Combinations of Theme Choice and Thematic progression

59

5. Conclusion

5.1 Conclusion

62

5.2 Pedagogical implications

63

5.3 Improvements and further study

64

6. Bibliography

65

List of Tables

1. The difference between Theme and content topic

2

2. Examples of Theme in declarative clauses

7

3. Predicated Themes

8

4. Textual and interpersonal Themes

9

5. Halliday's example of the most extended Theme

9

6. Examples of marked Themes

10

7. Subject grades received

23

8. Two paratactically linked clauses presented in reverse order

26

9. Two hypotactically linked clauses presented in original and reversed order

26

10. Some examples of conjunctive adjuncts

29

11. Some examples of modal adjuncts

30

12. Examples of circumstantial adjuncts

31

13. Examples 1 & 2 of omitted topical Themes

36

14. Examples 3 & 4 of omitted topical Themes

36

15. Example of use of rhetorical questions

44-45

16. Example 1&2 - Long experiential Themes

46-47

17. Example 3 & 4 - Long experiential Themes

47

18. 4 examples of simple linear progression

50-51

19. An example of the use of simple linear progression in orienting Themes

52-53

20. 4 examples of inference constant progression

55

21. 3 examples of repetition constant progression

57-58

22. The interaction of Theme choice and thematic progression

60-61

List of Charts

1. Use of orienting Themes

40

2. Median use of all orienting Themes

41

3. Total orienting Themes used

41

4. Use of textual Themes

42

5. Use of interpersonal Themes

44

6. Use of experiential Themes

45

7. Use of long experiential Themes

46

8. Use of simple linear progression

49

9. Use of simple linear progression in orienting Themes

52

10. Use of constant progression

53

11. Use of types of constant progression

54

12. Ratio of simple linear progression to constant progression

59

List of Figures

1. Simple Linear Progression

13

2. Constant progression

13

3. Circumstantial adjuncts

30

4. Circumstantial, modal and conjunctive adjuncts

32

5. Derived Theme

33

6. Split Rheme

34

7. An example of split-Theme

34

8. Gradient of content integration of Framing Adverbials

64

1. What is Theme?

1.1 The Origins of and Controversy surrounding Theme

1.1.1 The Historical Origins of Theme

In 1844, Weil proposed that the structuring of the clause reflects the train of thought of the

speaker/writer (henceforth the term speaker will stand for both). This enabled Weil to identify a

partitioning of the clause between what is already known to the speaker and listener/reader

(henceforth the term listener will stand for both) and what is foregrounded by the speaker as new

information. The known information already shared between speaker and listener constitutes a

"point of departure, an initial notion which is equally present to him who speaks and to him who

hears..." (Weil, 1844, p.29). For Weil, the point of departure is synonymous with the initial position

in the clause structure and contains information known to both speaker and listener. Weil therefore

combined psychological, syntactic and sociological aspects of communication in this first simplistic

definition of what was later named Theme. These various concerns of communication were to form

the basis of the many academic disagreements and debate which have surrounded this linguistic

concept right up to the present day.

1.1.2 Theme as content topic

Almost a century after Weil's observation of a two-part structure in the clause, the Prague School

linguist Vilem Mathesius first formulated the categorisations of Theme and Rheme as part of his

theory 'Functional Sentence Perspective'. For Mathesius "... an overwhelming majority of all

sentences contain two basic elements, a statement and an element about which the statement is

made" (Mathesius, 1975, p.81). The statement is realised in the Rheme, and it is made in relation to

the Theme.

For a recent definition, Michael Halliday of the Sydney School defines Theme in the

2014 edition of his 'Introduction to Functional Grammar' as:

Theme is the element that serves as the point of departure of the message; it is that

which locates and orients the clause within its context. The speaker chooses the Theme

as his or her point of departure to guide the addressee in developing an interpretation of

the message; by making part of the message prominent as Theme, the speaker enables

the addressee to process the message. (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014, p.89)

This is a lengthened and revised definition compared to that used in all previous editions of 'A

Introduction to Functional Grammar' up to 2004 (Halliday, 1985, 1994; Halliday and Matthiessen

2004). The above definition limits Theme to the point of departure, related to syntactic and social

factors, in particular the use of the empathy regarding the listener's perspective when the speaker

1

aims to convey a particular interpretation of a message. The earlier definition of Theme was

broader: "The Theme is what is being talked about, the point of departure for the clause as a

message" (Halliday 1967b, p.212). This earlier definition gave rise to problems concerning the

conflation of Theme with the 'content topic' of the text, that is 'what is being talked about' ('content

topic' must not be confused with the functional grammar definition of 'topic' discussed below in

section '1.1.3 Theme as Given/Known'). To illustrate this, Table 1 below shows an extract of text

from the corpus of the current study.

The difference between Theme and content topic

Theme

Rheme

In July 2005,

four terrorist attacks occurred in London, deliberately planned to

killed innocent bystanders.

The explosions

are believed to have been ordered and organised by the Islamic AlQaeda organisation and leaders of the Madrassas.

have not all been fully investigated due to their autonomy.

These extreme "brain

washing" schools

Those

which have been researched rely heavily on mindless repetition of

selected extracts from the Koran, delivered with both verbal and

physical threats.

Table 1 - Illustrating the difference between Theme and topic, lines 1a21 to 1a24 of the corpus of this study.

Although there is a shift from a focus on 'terrorist attacks' in the Rheme of the first sentence and the

Theme and Rheme of the second to 'brainwashing schools' in the last two sentences, both of these

arguments relate to the text's central concern, the 2005 London terrorist attacks. However, the first

sentence has a time adverbial in the Theme position. The content topic of the text is not exclusively

July 2005, so this Theme reflects much more ambiguously what the text is about. Downing states

that since content topic and Theme often do not coincide, the definition of content topic can be a

"rather elusive category" (Downing, 1991, p.121). Witte gives an example sentence about which

there could be disagreement concerning identifying the content topic:

Without care from some other human being or beings, be it a mother, grandmother,

sister, nurse, or human group, a child is very unlikely to survive. (Witte, 1983, p.319)

Witte identified 'a child' to be the content topic of this sentence. However, given that there is a long

Thematised prepositional phrase before the grammatical subject, it is possible to imagine that the

argument could be 'the consequences of a lack of care', or even 'the historical, limiting role of

women in society'. In most cases this ambiguity is resolved by reading the surrounding text.

Nevertheless, the conflation of Theme as point of departure for a message and content topic can be

regarded as overly generalising, especially when considering what Halliday defined as highly

2

marked Themes (see section '1.2 Halliday’s operationalisation of Theme').

1.1.3 Theme as Given/Known

In the preceding paragraphs the term 'content topic' has been used to signify the general semantic

content of a text, however many researchers have instead used the term 'topic' here. Mathesius'

position is that the point of departure is "that which is known or at least obvious in the given

situation and from which the speaker proceeds" (Mathesius, 1939, p.171). While initially stating

that Theme was analogous with given or known information, he later specified that "...theme need

not be a known piece of information" (In Daneš 1989, p.25). However, many researchers have

taken Theme to be synonymous with Given (see Gutiérrez Ordóñez 1997; Whitley 1986). The main

problem with this is that what is Given is determined by the listener, and therefore depends on what

any particular individual is able to infer from any given message. Halliday states that:

The Theme is what I, the speaker, choose to take as my point of departure. The Given is

what you, the listener, already know about or have accessible to you. Theme + Rheme

is speaker oriented, while Given + New is listener-oriented. (Halliday and Matthiessen

2014, p.120).

For Halliday Given and New form part of the information unit, which while often overlapping the

grammatical clause, does not necessarily do so. In fact, the information unit is defined semantically

and can be identified through changes in the use of tone groups by the speaker.

Both the structures of Theme and Rheme and Given and New are selected by the speaker, and very

often are realised in the same elements in a clause. However, this is not always the case. As an

example, Halliday and Matthiessen show how playing with the two systems can result in the

speaker "putting the other down, making him feel guilty and the like" (ibid, p.120).

// ^ are / you coming / back into / circu/lation //

(ibid, p.120)

Here, 'into circulation' is treated as the norm, and therefore Given information, while the New

information culminates in the tonally emphasized 'back'. This inversion of the information unit has

been mapped onto the Theme-Rheme structure to produce rhetorical effects. This approach

differentiates Halliday's stance on Theme from the Prague School linguists such as Mathesius and

Firbas, who at times have conflated Theme with Given. Halliday and Matthiessen (2014) make a

functional distinction between Theme and topic as understood from a functional grammar

perspective:

3

The label ‘Topic’ usually refers to only one particular kind of Theme, the ‘topical

Theme’ (see Section 3.4); and it tends to be used as a cover term for two concepts that

are functionally distinct, one being that of Theme and the other being that of Given

(ibid, p.89)

Halliday states that when Theme and Given are operationalised in the same word group, the

combination creates a Topical Theme, meaning that the definition of Theme cannot be simply

information which is given/known. The separation of Theme and Given has not however been the

position taken by many other linguists. Fries (1981) commenting on this distinction, labelled the

Prague School approach as 'combining' and Halliday's as 'splitting'.

1.1.4 Theme/Rheme in Communicative Dynamism

Jan Firbas, a Prague School linguist, states that the point of departure "is not the beginning of the

sentence, but the foundation-laying element of the lowest degree of Communication

Development.." (Firbas, 1987, p.145). The elements in a clause can be graded according to their

communicative dynamism (henceforth CD), with context-dependent elements having the lowest

level of dynamism while new information has the highest. While this scale of CD often increases

linearly through the progression of a clause, and therefore is mirrored in the Theme/Rheme

organisation, this is not necessarily always the case. Two other factors can interfere with this linear

progression, the context and semantic structure. If something is retrievable from the immediate

context, that is situational or textual, and is placed near the end of the clause, it can over-ride the

default increasing of CD towards the end of the clause. In relation to semantic structure, some

words can be context-independent, and if placed in the Theme position also work against the default

increasing of CD through the clause. McCabe (1999) explains: "some subjects are context

independent, especially in the case of verbs which denote appearance or existence on the scene, e.g.

A boy came into the room" (ibid, p.59). While Firbas's theory lends much greater flexibility to the

interaction between Theme and Given, in practice it is very difficult to operationalise when

performing analyses on real texts. Martin comments on this problem when he says that the theory

fails in that "it generally proves more practical to draw a line between Theme and Rheme" (Martin,

1992a, p.151). In addition, Hawes and Thomas (1997) refer to the difficulty also in assigning a

precise level of CD for different elements in a clause. Since Theme cannot be defined sociosemantically by identifying it with the content topic, or as Given information, and is difficult to

identify precisely using CD, many researchers have settled for a purely syntactic definition.

4

1.1.5 Theme as initial position

Many linguists (see Barcelona Sanchez 1990) have mis-interpreted Halliday's description of the use

of Theme in English, defining Theme as a solely syntactical function, that of being at the beginning

of a clause. Halliday does state that "...the element selected by the speaker as Theme is assigned

first position in the sequence" (Halliday, 1976, p.179), but later remarked that this previous quote

was "intended to say how the Theme in English is to be recognized [but] was taken as a statement

of how it is to be defined" (Halliday 1988, p.33 in Fries and Francis 1992, p.45). So, for Halliday,

Theme occurs in the initial clause position in English, and is often realised through information

which is Given or known by both speaker and listener, but these two elements do not suffice to

define the function of Theme.

1.1.6 Theme as message onset

Mauranen notes that despite all the theoretical ambiguity regarding Theme, it has remained an

intriguing concept for researchers due to "its interesting position at the interface of grammar and

discourse" (Mauranen, 1993a , p.104). While Theme is found in the initial position in the English

clause, its real functional definition relates to its role of structuring information within the clause

and between the individual clause and the text/context, or 'co-text', in which it is embedded. While

this formulation of the concept of Theme hints towards psychological factors involved, Halliday has

always preferred to focus on the social co-text in which the language act takes place.

Halliday's long time collaborator Christian Matthiessen (1995) did however explore the

psychological underpinnings of Theme, formulating his theory of Theme as contributing to the

creation of an 'instantial system' between speaker and listener. This system is created through

selection of elements from a general system.

From the speaker's point of view, an instantial system is the system of selections s/he has

to make in producing the text; from the listener's point of view, an instantial system is

the system that s/he can create out of the interpretation of the unfolding text.

(Matthiessen, 1995, p.22)

Theme plays a very important part in this construction of knowledge through any particular

instantial system as it "enables the process of interpretation by guiding the listener to a particular

node in the instantial network, making it unnecessary for him/her to search the whole network"

(ibid, p.27). Theme is thus psycho-sociological in nature, relating both to the construction of

knowledge between speaker and listener, but also strongly reflecting the communicative intention of

the speaker. Enkvist states that “What is optimal in textual terms depends on the speaker/writer's

intentions and motives, on the text type and on the text strategy" (Enkvist, 1984, p.58). Many

5

semantic and syntactic choices in the construction of a text contribute to the success or otherwise of

the communication. However, as McCabe notes, Theme plays a fundamental role in "the

expression of the speaker's perception of reality and the concerns of the speaker to communicate

that perception of reality to the listener" (McCabe, 1999, p.66). Theme orients the listener as to the

direction of the clause, the place of the new information presented in the clause in relation to the

surrounding discourse, and can also highlight cohesive or interpersonal considerations on the part of

the speaker (see section '1.2 Halliday's operationalisation of Theme' for a discussion of textual and

interpersonal Themes).

Returning to Halliday's definition of Theme which combines initial clause position with the point of

departure for the message of a clause, Davies explains that Theme initiates "the semantic journey",

adding that if a different starting point is chosen a different journey results (an oral statement by

Davies in McCabe, 1999, p.62). The organisation of elements in a sentence, and therefore the

choice of Theme, strongly influences the way the message can be understood by the listener.

McCabe takes the semantic sensitivity of the Theme position into account when she gives her

definition of Theme:

The definition of Theme used in this study places Theme at the point where the

grammar of the clause meets the surrounding text and also relates to the thought in the

speaker's mind. (ibid, p.54)

The initial clause position is not explicitly mentioned in her definition as it is simply a

phenomenological truism of English, but not necessarily of other languages, and so not of Theme as

a function. The function of Theme, labelled as 'message onset', includes its role in the grammar of

its encompassing clause, how it connects the information contained in this to its co-text, and how it

reflects the communicative intentions of the speaker. The coincidence of Theme with given/known

information between speaker and listener doesn't form part of the definition. To be able to

operationalise Theme as an analytical tool, the following section will focus on the concerns of the

researcher when analysing Theme in texts. The concerns covered are the range of Theme, that is

the dividing point between Theme and Rheme, the functional content of Theme (textual,

interpersonal and experiential), and Thematic Progression (henceforth TP).

1.2 Halliday's operationalisation of Theme

As regards the extent or range of Theme, Halliday remarks:

the Theme contains one, and only one... experiential elements. This means that the

Theme of a clause ends with the first constituent that is either participant, circumstance

or process. (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014, p.105).

Halliday and Matthiessen define an experiential element as "a representation of some process in

ongoing human experience; the Actor is the active participant in that process" (ibid, p.83). This

6

'Actor' can be realised in different ways. As a participant it is realised by a noun-phrase which often

coincides with the grammatical subject, but can also often be a noun-phrase which is thematised in

the initial clause position before the subject. As a circumstance it is realised through adverbial

groups and prepositional phrases. Finally, as a process it is represented through a verbal group,

which although in a declarative clause is not usually found in the Theme position, is thematised in

interrogative and exclamative clauses in English. If a nominal, adverbial, verbal group or

prepositional phrase occurs in the thematised clause initial position before the grammatical subject,

the latter is not assigned thematic status. This results in what Halliday terms a 'marked Theme',

whereas the occurrence of grammatical subject as Theme he calls an 'unmarked Theme'. Table 2,

taken from Halliday and Matthiessen's 'Introduction to Functional Grammar' (2014) summarises the

difference between the unmarked Theme and the marked Theme.

Examples of Theme in declarative clauses

Function

Class

unmarked

Theme

subject

Class example

nominal group: pronoun as

Head

I # had a little nut-tree

she # went to the baker's

there # were three jovial Welshmen

nominal group: common or

a wise old owl # lived in an oak

proper noun as Head

Mary # had a little lamb

London Bridge # is fallen down

nominal group: nominalization what I want # is a proper cup of

(nominalized clause) as Head coffee

marked

Adjunct

adverbial group

merrily # we roll along

Theme

prepositional phrase

on Saturday night # I lost my wife

Complement nominal group: common or

a bag-pudding # the King did make

proper noun as Head

Eliot # you're particularly fond of

nominal group: pronoun as

all this # we owe both to ourselves

Head

and to the peoples of the world [[who

are so well represented here today]]

this # they should refuse

nominal group: nominalization what they could not eat that night #

(nominalized clause) as Head the Queen next morning fried

Table 2 - Examples of Theme in declarative clause. Theme-Rheme boundary is shown by #

(Halliday and Matthiessen 2014, p.100)

Referring to an example of unmarked Theme given in Table 2, Halliday defines 'there' in 'there were

three jovial Welshmen' as an existential clause. 'There' only indicates the existence of something

which is then presented in the Rheme, leading to these types of clauses to be called 'presentative' or

7

'presentational' clauses (Van Valin and LaPolla, 1997, p.208). Although it could be argued that

'there' does not function as other non-existential subjects, it is certainly not a marked Theme, such

as 'merrily', 'on Saturday night', 'a bag-pudding', 'Elloit', 'all this', 'this' and 'what they could not eat

that night', all of which precede a clearly identifiable grammatical subject. For this reason, 'there',

and also 'it', in existential clauses are defined as grammatical subject and included in the analysis of

unmarked Themes. Two other example sentences of a complex structure given in Table 2 are 'what

I want is a proper cup of coffee' and 'what they could not eat that night the Queen next morning

fried'. In traditional grammar, the structure of 'wh- relative clause + be + complement' is defined as

a pseudo cleft (Huddlestone and Pullum, 2005). Halliday and Matthiessen instead define it as a

thematic equative, "it sets up the Theme + Rheme structure in the form of an equation, where

Theme = Rheme" (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014, p.93). Regarding the examples from Table 2,

the relative clauses 'what I want' (i.e. the thing I want) and 'what they could not eat that night' (i.e.

the thing(s) they couldn't eat that night) function as a nominal groups within the clause, they are an

examples of 'nominalisation' (see ibid, p.94). The difference between them again is that while both

fall into the thematic position, 'what they could not eat that night' is followed by the grammatical

subject of the main clause, 'the Queen'. It is therefore useful to consider 'what I want' as a

nominalised subject as again it helps to distinguish between marked and unmarked clauses.

One final element which utilises the existential subject 'it' is the predicated Theme, more commonly

referred to as a cleft sentence.

Predicated Themes

it was Jane that started it

it wasn’t the job that was getting me down

is it Sweden that they come from?

it was eight years ago that you gave up smoking

Table 3 - Predicated Themes (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014, p.122)

Halliday and Matthiessen's description of this function is that it identifies "one element as being

exclusive at that point in the clause" (ibid, p.122). These are more examples of equative

constructions, however there is a difference to the nominalisation examples in Table 2.

Nominalised Themes automatically map the Theme + Rheme structure onto the Given + New,

meaning that the Rhematic element "becomes strongly foregrounded information" (ibid, p.122),

something which is unexpected or improbable. Predicated Themes on the other hand can carry

new information at the same time as maintaining a contrastive meaning, i.e. 'that person, place, time

instead of another'. As in the case of nominalised Themes, only the whole construction of the

predicated Theme is considered as fulfilling the Theme role, i.e. 'it was Jane', 'it wasn't the job', 'is it

8

Sweden' and 'it was eight years ago'.

There may however be other elements for Halliday which precede the single experiential element

(participant, circumstance or process). These are textual and interpersonal Themes, the inclusion of

which can result in multiple Themes. Table 4 below summarises the sub-categories of textual and

interpersonal Themes.

Textual

Interpersonal

continuative

modal or comment adjunct

conjunction

vocative

conjunctive adjunct

finite verb operator (yes/no

interrogatives)

Table 4 - Textual and interpersonal Themes (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014,

p.107)

Regarding textual Themes, continuatives signal a move in the dialogue, that is a response or

introduction of a new point in a monologue (e.g. yes, no, well, oh, now...), conjunctions link clauses

together (parataxis links one clause to another through expansion, hypotaxis binds one clause to

another through projection), and conjunctive adjuncts perform the same function as conjunctions

but are realised through adverbial groups or prepositional phrases. In relation to interpersonal

Themes, modals or comment adjuncts signal the speaker's judgement or attitude, vocatives are

typically names, or other items, used to address someone, and finite verb operators are the small

group of auxiliary verbs thematised in unmarked yes/no interrogatives.

The example that Halliday and Matthiessen (2014) use for the most extended Theme is given in

Table 5 below.

well

but

then

surely

Jean

wouldn't

the best

idea

be to join

in?

cont

stru

conj

modal

voc

finite

topical

Theme

Rheme

Table 5 - Halliday's example of the most extended Theme (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014:107)

In the example given in Table 5, the first experiential element, 'the best idea', coincides with the

position of grammatical subject and is named the topical Theme. However, while there is the

conflation of Theme and grammatical subject after textual and interpersonal Themes, when a

circumstantial Theme, or adjunct (such as 'merrily we roll along' or 'on Saturday night I lost my

wife' from Table 2 above), or a marked nominal group, or complement (such as 'Elliot' or 'a bag

9

pudding' from Table 2 above) occur in the Theme position, the following grammatical subject is not

included in the thematic analysis.

1.3 An alternative operationalisation of Theme

Objections to Halliday's limitation of the range of Theme to one experiential element relate to the

utilisation of Theme as a tool in discourse analysis. There are various studies of Theme in

languages other than English that use alternative formulations of the concept. Steiner and Ramm

(1995) show that in German Theme does not need to include an experiential element and

Hasselgård (1998) argues that the finite verb can be thematic in declarative clauses in Norwegian.

In another cross-lingual study, Martin and Rose argues that including the subsequent participant

after a circumstantial Theme 'enables us to map a text's method of development, and to relate it to

comparable texts in other languages.' (Martin and Rose, 2003, p.133). Likewise, Arus, in a

comparative study of Theme choice in English and Spanish, states that there are some 'thematized

circumstances that exhaust the thematic potential [and other] thematic circumstances which do not.'

(Arus, 2006, p.13). While these studies are interesting as they relate to the function of Theme,

which should in Halliday's view be applicable to any language, there are many other studies that

argue for a re-formulation of the application of Theme in English. Various studies (Davies 1997;

Fries 1995; MacDonald 1992 1994; Gosden 1992 1993; Lowe 1987) argue that unmarked Themes

are used for 'topic continuity' (that is, continuity of the main argument of a text), whereas marked

Themes are used for change, discontinuity. The marked Themes in Table 6 below are taken from

the corpus of the present study. They are used to focus on temporal settings, while the subjects

instead indicate the main participants in this text, gay men and women.

Examples of marked Themes

Marked Theme

Rheme

Subject

Until the late 19th century,

most gay men and women

Even up until the early years of most gay men and women

the 20th century,

did not realize that there was a

term for their attraction to

others of the same sex.

were afraid of not only what

others would think of them

Table 6 - Lines 2c8-2c9 taken from the corpus text‘Why historically, has San Francisco been

regarded as the home of the gay rights movement?’

Thematising the grammatical subject allows then both for the analysis of topic continuity in a text

10

as well as the identification of the main participants. Using the Hallidayan operationalisation, only

'Until the late 19th century', 'Even up until the early years of the 20th century' would be considered

Thematic. While these are certainly connected to the argument of the text, the association of San

Francisco with the gay rights movement, they do not track the central content topic, the experiences

of gay men and women. Charolles (1997, 2005) identifies these types of adverbial phrases as

'indexation links', as they provide cohesion not just to the sentence in which they are found, but to

the text from that point on (see the second sentence in Table 6 above). Despite this special function

of cohesion, these adverbial phrases are connected to but do not track the central concern of the text

as the topical Themes do. For the current study, I will use North's (2005) distinction between

orienting and topical Themes. Orienting Themes include textual, interpersonal, experiential

Themes. The last category covers any experiential element (mostly circumstantial adjuncts) which

do not perform the role of participant in the clause. The topical Theme fills participant roles within

the clause, and as North declares "is normally the grammatical subject, or occasionally another

element such as a thematized complement or predicated Theme" (North 2005, p.437, see also Table

2 for thematized complements and Table 3 for predicated Themes). No marked complement

Themes and only one predicated Theme (see line 3g12 in the corpus) were found in the corpus of

the present study. For this reason, apart from the exception mentioned above, for the purposes of

the present study the topical Theme can be thought of as being realised exclusively through the

grammatical subject.

1.4 Topical Themes

MacDonald says ‘the subject slot is...the most important spot for determining what a writer is

writing about and how questions about epistemology, construction or agency enter into the writer’s

thinking’ (MacDonald, 1992, p.539). If orienting Themes show the rhetorical importance of

thematising elements for the purposes of building coherence in a text, topical Themes reveal most

clearly what the main concerns of the writer are. Forey analysed the use of Theme in workplace

texts, finding that "the highest frequency of occurrence of Theme choices in the present corpus were

unmarked Themes, and the majority of these were simple Themes" (Forey, 2002, p.128). Simple

Themes are analogous to the topical Theme when realised through the grammatical subject.

Regarding the textbook 'Working with discourse' (Martin and Rose 2003), Forey also notes that "the

choice of Subject/Theme is pertinent because the writer may include evaluation within their choice

of Subject" (Forey, 2002, p.128-9). Including the topical Theme allows the present study to

consider all types of thematic structuring, from the use of unmarked orienting Themes which

11

contribute to local cohesion, to topical Themes which track the main concerns of the writer.

1.5 Thematic Progression

The formulation of the idea of TP in the 1970s and 80s was motivated as a response to attacks on

the conceptual validity and unity of the idea of Theme itself. According to Levinson

"terminological profusion and confusion, and underlying conceptual vagueness, plague the relevant

literature to the point where little may be salvageable" (Levinson, 1983, p.25). To this and other

such positions, Halliday replies that:

The problem is that it takes too long to present the grammar step by step in this way; so

we tend to start with the labels, and it is forgotten how they were arrived at and what

they are for. Thus, when we investigate the proportionality in English set out above, we

find that the variation in sequence means something: ‘being first expresses a function in

the clause, and we give this a label ‘Theme’... (Halliday, 1994, p.xxxii)

The tendency to want to impose 'traditional grammar' labels on the constituents of functional

grammar devalues the descriptive power of this system. As Van Huffel points out, "the essence of

Theme... should be that it functions within text" (Van Huffel, 2007, p.15). Daneš (1974), who was

part of the Prague School, was the first to identify that Themes can relate to other clauses in

different ways. Fries (1981) validated this theory of TP through the observation of different types

of TP correlating with different genres of text. More recently, Wei Jing notes in her review of

research articles from 1983-2013 into Theme-Rheme: "The earliest articles focused on Theme types

in learner English, and later, scholars examined thematic progression" (Wei Jing, 2014, p.76). The

growing popularity of thematic progression as a means of analysing texts reflects a general

acceptance of its validity as a method for highlighting cohesive strategies.

The following studies focus on two patterns of TP in professional and student writing. Referring to

three articles which have influenced the present study (Daneš 1974; McCabe 1999; North 2005),

Soleymanzadeh and Gholami state that:

The bigger this ratio of simple linear progression (SLP) to constant progression (CP),

the better would be an essay according to argumentative essay writing norms

(Soleymanzadeh and Gholami, 2014, p.1813)

Figures 1 and 2 below illustrate these two types of TP, as identified by Daneš (1974), with examples

given from the corpus of the present study.

12

Simple Linear Progression

Theme

Rheme

Following the first slave ship

of 1691, their numbers

grew at an incredibly fast rate to support the massive growth of

cotton and other labour intensive agriculture.

These agricultural areas

lay largely in the southern states.

It was these southern states

that primarily formed the centre of African American presence,

where they were numerically by far the majority ethnic group.

Figure 1 - Simple Linear Progression, from lines 3g9-3g11from the corpus of the present study

Constant progression

Theme

Rheme

The First World War

was fought across Europe, the European colonies and the

surrounding seas from 1st August 1914 until 11th November 1918.

It

created a major struggle which altered enormously the political,

economic, social and cultural nature of Europe.

This war

was felt in one way of another throughout the world as each nation

from every continent indirectly or directly entered the war.

Figure 2 - Constant progression illustrated with lines 3e14-3e16 from the corpus of the present

study

Figure 1 illustrates simple linear progression where the Theme of the second and third sentences are

taken directly from the Rheme of the preceding sentence. The choice of Theme in the second and

third sentences of Figure 2 show an example of constant progression as these Themes are directly

related to the Theme of the preceding sentence. Fries (1983) found that academic texts employ a

high percentage of SLP as this enables expansion and explanation which is important when

discussing complex issues. SLP is integral to the meta-functions of defending or opposing an idea

while convincing the reader to agree with the argument that Reid (1988) identified as central to

academic argumentative texts. Ren, Cao, Yuanyuan and Li carried out a pedagogical study to help

students improve text unity through their 'Thematic Operational Approach'. In analysing a sample

corpus of academic writing exercises, they found that "that the most frequently used pattern is

simple linear progression " (Ren et al., 2009, p.144). However, Watson-Todd, Khongput,

Darasawang identified the problem of a lack of SLP (which they term sequential progression),

"texts with a relatively low proportion of sequential progression could be viewed as potentially

problematic" (Watson-Todd et al., 2007, p.9). Finally, various other studies (Jalilifar 2010; Wang

13

2007; Almaden 2006; Belmonte & McCabe 1998) have found an overuse of CP as compared to SLP

in student undergraduate writing. They highlight the particular difficulties that non-native English

speakers find in building cohesion into their academic texts. These issues and more, such as

English learner writing cohesion, language transfer, language proficiency, disciplinary variation and

the effect of instruction, will be investigated in greater detail in the following section.

14

2. Studies of the use of Theme in academic writing

2.1 Theme and Thematic progression and cohesion in learner English writing

As regards the construction of a text by English learner writers, Thompson says that thematisation

greatly contributes to "how speakers construct their messages in a way which makes them fit

smoothly into the unfolding language event" (Thompson, 2004, p.141). This smooth unfolding of

the language event depends heavily on the overall semantic organisation of a text. As Martin

explains:

The idea behind Theme and Rheme need not be confined to the clause only, but can be

extended to the paragraph, section, or entire text, depending on the number of layers in

the text (Martin, 1992a, p.156).

However, the operationalisation of this principle, that is selecting Themes appropriate to the culture

of a particular academic field, presents difficulties especially for non-native English speakers.

Hoey (2005) notes that only experienced readers who are fully integrated into an academic

discipline are culturally primed to expect the structural and semantic organisation of Theme and

Rheme.

Regarding experimental studies, Ma (2001) showed that English learners who achieved higher

grades used proportionally more SLP and CP patterns of TP. Wang (2010) extended this study by

showing that to achieve higher overall grades students not only need to employ a range of TP (in

this case CP, SLP, split-Theme and split-Rheme (see section '3.2.3 Types of TP counted' for

explanations of split-Theme, split-Rheme)), but also use particular types of Theme, like the multiple

Theme and the clausal Theme (i.e. subordinate clause experiential Themes). These two studies

demonstrate that the successful use of Theme in academic writing cannot be accounted for through

a simple ratio like SLP to CP as suggested by Soleymanzadeh and Gholami (2014).

Typical problems that non-native English speakers encounter include using Themes which are not

connected to the preceding or following Themes, resulting in a lack of cohesion (Zhang, 2004;

Cheng, 2002). The distinctions between highly coherent non-native academic writing and that of

low coherence can be seen particularly clearly in Theme choice and thematic progression. Melios

found in English learner writing that:

high scoring coherent essays employ dense and complex nominal groups in ideational

themes, a wide variety of textual themes, and different forms of thematic progression...

[while] low scoring papers frequently overuse unmarked themes of simple nominal

groups or pronouns and overuse theme reiteration in a way that makes the text difficult

15

to follow and appear to lack development (Melios, 2011, p.iv).

The forms of TP used by the writers of the high scoring essays included the use of SLP and CP,

while low scoring essays used only topical Themes, with some CP which was achieved only

through repetition. As evidenced by some of the above studies, non-native students often have to

contend with language transfer from their mother tongue when trying to select Themes and build

TP. To successfully employ Theme and Rheme in constructing a coherent and cohesive text, the

English learner must know both which types of Themes (textual, interpersonal and experiential) are

most common to a particular discipline as well as be able to use these in certain disciplinaryspecific patterns of TP.

2.2 Language background and Theme use

In relation to correlations of first language and Theme choice, the selection of adverbial groups used

to link clauses together has received much attention. These adverbial groups are analogous to

Halliday's category of circumstantial Themes. Chinese students often misused linking adverbials,

mistaking 'on the contrary' for 'however' (Crewe, 1990), or using 'on the other hand' without

intending to employ contrast (Field and Yip, 1992). Green, Christopher and Lam found that

Chinese learners had a greater tendency to place "topic-fronting devices (beginning For and

Concerning) and logical connectors (Besides, Furthermore and Moreover) to introduce new

information" (Green et al., 2000, p.99). This led to a breakdown in cohesion as the default

information structure of Given + New was too often inverted. Likewise, Rowley-Jolivet and CarterThomas (2005) found that native speaker presenters at scientific conferences used more locative

adverbs (here, there) in the Theme position, which entails subject-verb inversion to maintain the

Given + New structure, in oral presentations than non-native speakers. This allowed the native

speakers to employ SLP structuring in linking following clauses to the initial clause which

described a visual support. When comparing Hong Kong English learners' writing with that of

professional native speakers, the learners overused 'moreover, nevertheless, therefore' (Milton and

Tsang, 1993), while Swedish students of English underused resultative (therefore, thus,

accordingly) and contrastive (however, despite, nonetheless) linking adverbials (Altenberg and

Tapper, 1998). Herriman states that related to Swedish English learners:

They would, in particular, benefit from an increased awareness of how Themes and

Theme progressions may be used to manage the logogenetic build-up of information as

it accumulates in their texts. (Herriman, 2009, p.24)

A final study found overuse of linking adverbials both by Chinese and British students, the former

16

overusing 'so, and, also, thus, but', while the latter overused 'however, so, therefore, thus,

furthermore' (Bolton, Nelson and Hung 2002). Crewe (1992) hypothesized that such overuse of

linking devices may indicate a tendency for surface logic, an attempt to disguise the poor

structuring of the underlying text.

2.3 Proficiency level and Theme use

In Jalilifar's study of Iranian student's oral proficiency in English, he found that "students’ level of

language proficiency monitor the use of linear and split thematic progression chains" (Jalilifar,

2010, p.31). Likewise Medve and Takač (2013) also found that the use of SLP increased in line

with increase in proficiency levels of students. However, Wei (2013a) found that as learners'

proficiency increases, their use of Themes becomes more like that of native speakers', particularly

related to the frequency of topical Themes, textual Themes, interpersonal Themes and Theme

markedness. The difference in the findings of these two studies is related to the register of the

speech involved, with Jalilifar (2010) and Medve and Takač (2013) concentrating of academic oral

activities whereas Wei (2013a) focused on general language fluency. However, other studies such as

Soleymanzadeh and Gholami (2014) found no links between students' IELTS scores and scores

based on TP. They suggest including TP in the marking grid for the IELTS exam. Also, Donohue

and Erling (2012) found no correlation between a diagnostic language test 'Measuring the Academic

Skills of University Students' and student grades in three subjects. Despite these observations, it

seems likely that proficiency has as much or more influence on Theme use as linguistic background.

One area in which both high proficiency native and non-native speakers might struggles is adopting

the Thematic tendencies of their particular discipline(s).

2.4 Disciplinary differences in the use of Themes

The following studies have been carried out at undergraduate level into inter-disclipinary

differences in Theme use. Ebrahimi and Khedri (2011) compared research article abstracts in

Chemical Engineering and Applied linguistics, finding that Chemical Engineering abstracts

employed both interpersonal (14% to 5%) and textual (27% to 23%) more than Applied Linguistics

abstracts. They also found that SLP and CP were used more in the Chemical Engineering abstracts.

Idding (2008) investigated the different uses of Theme in the Humanities and Biochemistry, finding

that while the percentage use of textual Themes was the same in both subjects, the Humanities

students used more interpersonal Themes, and also more unmarked, topical Themes (i.e. simple

17

Themes). From the two studies, it seems clear that the academic writing in the humanities tends to

employ less orienting Themes as well as less thematic progression strategies when compared to teh

natural sciences. Ghadessy (1999) compared article abstracts from 30 different academic

disciplines, finding that Geography articles used many more simple Themes than Finance (84.6% to

47.4%), while Finance used many more multiple Themes that Plant Pathology (52.6% to 10%) and

Sociology used more unmarked Themes than Film and Cinema studies (100% to 70.6%). Although

he presented a more complex picture through involving so many disciplines, again the tendency of

Geography and Sociology to use more simple Themes than other disciplines is evident. Whittaker

(1995) investigated the use of Theme by authors of academic articles in Economics and Linguistics.

She found that these academic disciplines employ many experiential Themes, while both used very

few interpersonal Themes (under 10%). This can be attributed to the need to present arguments as

objectively as possible in both disciplines. The differences found in these studies indicate a high

level of disciplinary variation concerning what is normally thematised in a clause, though clearly

more research is need to map these more precisely. The studies also reveal some general

characteristics of academic writing, such as the rare use of interpersonal Themes.

Given that the corpus of the present study consists of 26 history papers, some papers which looked

at the use of Theme in the humanities follows. Some studies which relate more closely to this

include Taylor (1983) and Lovejoy (1998) who both found that circumstantial Themes in academic

textbooks were more common in history textbooks, and in the case of Lovejoy also psychology

textbooks, as compared to textbooks of the natural sciences. This is consistent with the studies

above which showed limited use of textual and interpersonal Themes in the humanities (Ebrahimi

and Khedri, 2011; Idding, 2008). Another study involving history papers was written by North

(2005), in which she compared Theme choice according to the academic disciplines of the

participants. She found that the higher grades achieved by students with a background in arts

compared to those whose background is in the natural sciences, which was correlated to their

greater use of orienting, especially circumstantial Themes referring to the views of historians. One

possible reason why the arts and not the science students wrote in this way is that the former have

"a greater tendency to present knowledge as constructed and contested, rather than as a plain matter

of fact" (ibid., p.449). This reflects the epistemological approach of the arts students, in which they

are used to creating "interplay between data and argument" (Becher 1989, p.87). North concludes

that "variation in disciplinary culture is reflected in academic writing, leaving its trace in the

linguistic and rhetorical features of disciplinary texts" (North, 2005, p. 431). Concerning students

18

of history, Greene highlights how arguments must be built through the weighing up of competing

arguments, where "what is said is inseparable from who said it" (Greene 2001, p.527).

2.5 Instruction in the use of Theme and textual cohesion

The consideration given to cohesion in many academic writing textbooks focuses almost

exclusively on the use of textual Themes, that is 'reference words' or 'transition expressions', which

are analogous to Halliday's conjunctions and conjunctive adjuncts (see Bailey 2015; Haynes 2010;

Gillett, Hammond and Martala 2009; Hartley 2008; Butler 2007; Kotzé 2007; Murray and Moore

2006; Davis and Liss 2006; Savage and Mayer 2005; Zemach and Rumisek 2005; Jordan 2003;

Leki 1998; Hogue 1996). For example, Hennessey claims in his book 'Writing an Essay' that

cohesion and unity can be achieved through “using a network of connectives” (Hennessey, 2002,

p.71). Likewise, Donald, Moore, Morrow, Wargetz and Werner state that “coherence is achieved

through transition”, meaning “a transitional word or phrase” (Donald et al., 1995, p.270). Alonso

and McCabe (2003) openly criticize this approach, stating that while academic writing materials

focus on cohesive devices, little attention is given to TP in example texts. One widely used

textbook, 'Writing Academic English' by Oshima and Hague (2006), does contain one exercise (see

Oshima and Hague, 2006, p.37) which focuses on how a key element of a paragraph topic sentence

is picked up in the other sentences of the same paragraph. This does not constitute a thorough focus

on TP, failing to highlight the flow, or lack thereof, between each sentence with the next. The main

focus of these textbooks is generally on specific argumentation approaches such as description,

classification, comparison/contrast, persuasion, cause and effect, definitions, examples, and on

broadly structural elements such as topic sentences, introductions, conclusions, paragraph ordering,

and also on the process of writing, including note-making, researching, planning, drafting, and

reviewing, all of which come under the field 'Academic literacies'. There is a wide variety of

research carried out on the subject of academic literacies. Coffin and Donohue (2012) carried out a

review study focusing on the differences of the approach to academic writing between academic

literacies and systemic functional linguistics (henceforth SFL). They state that while academic

literacies has focused on "ethnographic investigation... identifying practices, student identities, and

conflicts that individual language users experience in university writing" (Coffin and Donohue,

2012, p.64), SFL instead focuses on "linguistic analysis to establish the nature of disciplinary

discourse... research and pedagogy have concentrated on texts, language in use and the language

system" (ibid, p.64). While both are acknowledged as contributing to issues surrounding academic

19

writing, the latter forms the basis of the current study due to its ability to reveal structures and

practices in academic texts which might be used to produce teaching materials. Returning to the

published academic writing textbooks mentioned at the start of this paragraph, Bohnacker observes

that "discourse-driven word order patterns are... largely ignored in descriptive grammars, teacher

training and language teaching materials" (Bohnacker, 2010, p.133). This oversight can have

negative consequences on their readers' ability to formulate a text which conforms to both general

academic style as well as that of their particular discipline, which can be revealed through SFL

analyses.

While TP has been overlooked in academic writing textbooks, there are many research studies

focused on the pedagogical importance of teaching TP. For instance, Wang (2007) identifies the

problem of the brand new Theme:

The problem of a brand new Theme is extremely common in the work of inexperienced

writers, who put new information in Theme position. For example, the illiteracy rate is

quite high in some rural areas. Here Theme 'The illiteracy rate' is in Theme position in

the sentence, however this is the first mention of this information. Where this goes

wrong, the communication can suddenly break down at the sentence level (Wang 2007,

p.167).

By fully incorporating this typical student error into the flow of her research article, that is without

using inverted commas, Wang gives a powerful example of the type of the confusing effect of the

type discontinuity typical in student academic papers. She concludes her article by imploring

academic writing teachers to look beyond traditional grammar notions to more discourse-based

approaches, such as TP. In a review of academic English teaching at the University of Sydney,

Jones noted that students had difficulties "not so much in grammar and sentence structure as in the

ability to fashion a coherent argument where sentences and ideas relate to one another without

missing links of meaning" (Jones, 2007, p.145). Meanwhile, Watson-Todd et al. (2007) investigated

the relationship between connectedness of discourse, of which TP is central, and professor feedback

to students at a Thai university. They found that professors' comments on students' writing reflected

more "the actual content and the form of argumentation more than on the connectedness" (WatsonTodd 2007, p.20). While it could be argued that subject teachers will always be more concerned

with the contents of an argument rather explicitly with its structure, this neglects the evidence that

certain types of TP, particularly the use of SLP, correlate with student attainment and academic

journal writing style (see sections '2.1 Theme and Thematic progression and cohesion in learner

English writing' for student attainment studies, and section '2.4 Disciplinary differences in the use

of Themes' for journal writing styles).

20

In relation to TP intervention studies, Ebrahimi and Ebrahimi (2012a) separated students into three

groups who followed different academic writing courses. The results were that students who had

only followed a traditional grammar course were unlikely to use SLP and CP, those who had

additionally completed a course on paragraph writing performed better, while those who had also

followed an essay writing course were the most proficient in handling Theme choices and TP. Ren

et al. found in their pedagogical experiment that at the end of the study the participants not only

"know how to use the acquired thematic progression consciously and properly in their writing, but

are even able to notice new TP patterns... themselves. They are satisfied with their progress in their

writing" (Ren et al., 2009, p.144). In the article 'Teaching coherence to ESL students: a classroom

enquiry' by Lee (2002), the value of raising students awareness of coherence is seen as vital for

improving general academic style. Likewise, Watson-Todd et al. argue that "a greater awareness of

the usefulness and manifestations of connectedness may allow tutors to give specific comments on

cohesion and coherence for the benefit of students' writing" (Watson-Todd et al., 2007, p.22). In

Albufalasa's (2013) doctoral thesis into the teaching of thematic structure and generic structure to

EFL students, she found that the two experimental groups which included TP instruction "were

more successful in using the different thematic patterns across their essays to interweave their ideas

to maintain more cohesive and coherent essays" (Albufalasa 2013, p.162). Finally, regarding

Martin's statement above that Theme can be analysed at different levels in a text, Xudong (2003)

used thematic analysis as a self-revision technique with two students where he found that by

analysing macro-level (whole text) Themes and their connected hyper-Themes (paragraph), students

were able to understand and improve the cohesion of their texts. The present study will seek to

discover whether there is a correlations between content-based subject grades in history and Theme

choice and the use different types of TP. If such is the case, this would indicate that the students

achieving lower grades could have benefited from instruction in the use of Themes in building a

logical, cohesive text. It would also support the above-mentioned studies advocating the explicit

teaching of TP, as well as serve to highlight the negative effect from its omission from academic

writing textbooks.

21

3. Corpus and procedure

3.1 The corpus

The Corpus consists of 26 extracts from the International Baccalaureate (henceforth IB 1) Extended

Essay, totalling 12,017 words. The IB provides the most widely recognised primary and secondary

level international qualifications in the world. The programme covering the last two years of high

school is called the 'Diploma Programme' (henceforth DP) and is the most widely studied of the 3

IB qualifications. There is great emphasis on international understanding and community

engagement in all 3 programmes, but especially in the DP. For example, students undertake

community work through the 'Community, Action, Service' initiative 2 and are encouraged to reflect

on what constitutes knowledge in the 'Theory of Knowledge' course 3. They also have to undertake

an individual research project on an issue of their choice, which culminates in the writing of a 4,000

word academic paper, called the Extended Essay (henceforth EE). In the guidelines provided by the

IB for writing the EE (Extended Essay Guide, 2013), they state that the EE "acquaints them [IB

students] with the independent research and writing skills expected at university" (Extended Essay

Guide, 2013, p.2). This is the first time that the majority of the IB students have had to write an

academic paper which includes:

- Title Page

- Abstract

- Contents Page

- Introduction

- Body (development/methods/results)

- Conclusions

- References and bibliography

- Appendices

(ibid, p.15)

The IB specifies that the paper must take the form of "formally presented, structured writing, in

which ideas and findings are communicated in a reasoned and coherent manner, appropriate to the

subject or subjects chosen" (ibid, p.2). In regard to the findings of the use of circumstantial themes

in history academic papers (North 2005; Greene 2001; Lovejoy 1998; Becher 1989; Taylor 1983), I

chose to analyse extracts from 26 history EEs (see section '3.2 Analytical framework' for details of

how the length of the abstracts was determined). I obtained the papers from two sources, 21 papers

dating from 2009-2014 were obtained from the 'International Bilingual School of Provence'

1 See www.ibo.org

2 See http://www.ibo.org/en/programmes/diploma-programme/curriculum/creativity-action-and-service/

3 See http://www.ibo.org/en/programmes/diploma-programme/curriculum/theory-of-knowledge/

22

(henceforth IBS, see www.ibsofprovence.com) and 5 from the IB publication '50 More Excellent

Extended Essays' (2011). The reason for including these latter papers was to extend the range of

subject grades in the study. The 21 IBS papers received grades from B to E, with only 1 paper

achieving a B, whereas the five papers taken from the IB publications appropriately all received

grade As. This means that the grade distribution over the whole corpus was more even, see Table 7

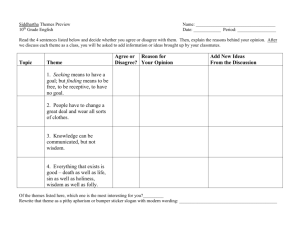

below.

Subject grades received

Grades

A

B

C

Frequency

5

1

9

Table 7 - Frequency of subject grades received in the corpus

D

E

9

2

All essays are graded by an external examiner who is a subject expert, often a former or present IB

teacher connected to a different IB school. These grades are arrived at through the assigning of the

best matching descriptors related to 11 criteria:

- Criterion A: Research question

- Criterion B: Introduction

- Criterion C: Investigation

- Criterion D: Knowledge and understanding of the topic studied

- Criterion E: Reasoned argument

- Criterion F: Application of analytical and evaluative skills appropriate to the subject

- Criterion G: Use of language appropriate to the subject

- Criterion H: Conclusion

- Criterion I: Formal presentation

- Criterion J: Abstract

- Criterion K: Holistic judgement

(summarised from Extended Essay Guide, 2013, p.23-28)

Although only Criterion G explicitly addresses the language content of the EE, the objective of the

current study is to correlate the subject grades arrived at through the assessment of all these criteria

with various aspects of thematic choice and progression. Firstly, to ensure that there are not any

other variables which influenced the grades assigned, the characteristics of the students who wrote

them will be analysed.

With respect to language content, the IB states in its grading guidelines that regarding 'Criterion G Use of language appropriate to the subject:

This criterion is not meant to disadvantage students who are not writing in their first

language—as long as the meaning is clear, the historical content will be rewarded

(Extended Essay Guide, 2013, p.97).

23

The IB states both that students must engage in "high-level research and writing skills, intellectual

discovery and creativity" (ibid, p.2), but also that they must "present ideas in a logical and coherent

manner" (ibid, p.31). However, no specific language expectations are used in the marking criteria.

The IB is taken by more non-native English speakers than native English speakers each year.

Ballantyne and Rivera report that "There were a total of 88,892 second language candidates for the

IBDP across the five year period 2008-12" (Ballantyne and Rivera, 2014, p.4). In relation to the

corpus of the present study, there were 10 English native speakers, 9 of whom came from the

United Kingdom, with one coming from Canada, and 16 non-native English speakers from

Germany (6), France (4), Italy (1), Sweden (1), Poland (1), Lebanon (1), Japan (1), and Costa Rica

(1). There was no correlation between first language and subject grades (r=0.1132, p<0.625), which

supports the IB's aim to not discriminate based on students' first languages. However, examiners

who grade the EE might discriminate based on language use, in particular the use of Theme choice

and progression, irrespective of the first language of any particular student. Considering further

variables, there were 10 male students and 16 female, although again no correlation was found

between grade achieved and gender (r=0.416, p<0.060). The students had a variety of History

teachers during their IB History courses, but both this (r=0.1432, p<0.543) and the year in which

they completed their EEs (r=0.1632, p<0.459) do not correlate with the subject grades they

received.

The preparation and guidance afforded to the students during the writing of their EEs at IBS and the

approaches used in specialized preparation textbooks did not give any unequal advantage to any

individual students. The sessions undertaken with students at IBS regarding the language content of

the EE focused mainly on editing exercises aimed at "upgrading student writing to a more formal

register" (quotation from an e-mail from Patricia Reboulet, a teacher and EE coordinator at IBS,

2015). Academic writing textbooks, such as those reviewed in the section '2.3 Theme in academic

writing', are not used, as they are "laborious and frustrating" (ibid, 2015). Instead, some websites

such as Purdue Owl1 are used, especially teaching the referencing of source texts and for attaining

the correct overall format. Subject tutors also cover the grading criteria as detailed in the 'Extended

Essay Guide' (2013), which includes subject specific language criteria, but as already shown

through Criterion G for history papers, does not guide students as to specific linguistic expectations.

As regards textbooks, there are two publications currently available: 'The IB extended essay: An A+

in 6 easy steps!' (Céspedes, 2013); 'Three: The ultimate student's guide to acing the extended essay

1 See https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/

24

and theory of knowledge' (Zouev, 2008). Both titles cover areas such as:

- Finding a topic

- How to carry out research

- Analysis and Evaluation

- Citing sources in the text

- Writing the abstract/introduction/conclusion etc.

While these are no doubt very helpful for many IB students, the books again follow the same basic

approach of guiding students through the process of writing, rather than dissecting the finished

product that they will be expected to produce for functional linguistic features. The approach

therefore is very similar to that of the general academic writing textbooks reviewed in the section

'2.3 Theme in academic writing'. All these study supports neglect a significant body of research

which highlights the links between disciplinary, and general academic practices, and linguistic

features in academic texts of different disciplines (as reviewed in the section all of section '2.

Studies of the use of Theme in academic writing'). Referring again to the IB Extended Essay

Guide, Criterion E for history states:

Students should be aware of the need to give their essays the backbone of a developing

argument... Straightforward descriptive or narrative accounts that lack analysis do not

usually advance an argument and should be avoided

(Extended

Essay Guide, 2013, p.97).

The title of Criterion E is 'Reasoned argument'; however the construction of such types of

arguments and familiarity and mastery of associated linguistic features, especially Theme choice

and progression, are mutually reliant factors. If students are aware of how other texts build in logic

and reasoning, they come to know not only how to use certain linguistic devices but also how to

build a reasoned argument itself. This proposition is backed up by several intervention studies

mentioned earlier (Albufalasa 2013; Ren et al. 2009; Watson-Todd et al. 2007; Xudong 2003).

As to the texts chosen to be a part of the corpus, all orthographic, punctuation and grammatical

errors contained in the original texts have been faithfully reproduced in the corpus of this study. On

some occasions some simple assumptions were made about the intention of the writer, for example

the repeated use of the word 'German' instead of 'Germany' in 'Paper 1b - ‘How significantly each

event contributed to Hitler’s elections as chancellor in 1933’. Given the supporting context, the

author considers these assumptions to be of low subjective value and so has not made any special

emphasis regarding this in the analysis.

25

3.2 Analytical framework