356198496-Rule-58-Case-Digests

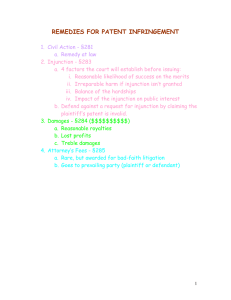

advertisement