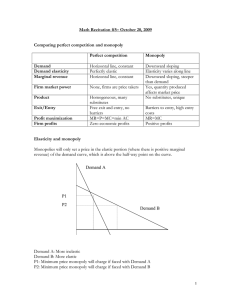

Managerial Economics Notes: Basic Concepts & Decision Making

advertisement