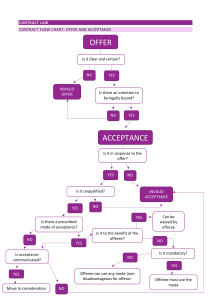

lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 Contract law exam Complete Note - 2019-2020 lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES Formation of contract A contract is a legally binding promise or agreement, oral or written, between two parties, the breach of which sounds in a legal remedy. A. Offer An offer is an expression of willingness to enter into a contract on certain terms, where the offeror indicates that an acceptance is invited. MacRobertson Miller Airline Services v Commissioner of State Taxation • • • • Objective Test: Carbolic Smoke Ball Case held whether it would be appear to a reasonable person in the position of the offeree that an offer was intended, and a binding agreement would be made upon acceptance. It does not matter whether the offeror in fact intended to make an offer; the court determines the offeror’s intention objectively. “...whether particular conduct amounts to an offer is a question to be decided on the facts of each case” Australian Woollen Mills Pty Ltd v Cth Cannot be an Invitation to treat (Pharmaceutical Society v Boots), Puffery (Carbolic Smoke Ball), Supply of information (Stephenson, Jacques & Co v McLean) and Counter-offers (Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-o Corp). An offer will only be effective all of its terms are communicated to the offeree. An offer cannot be accepted unless the acceptor is aware of the existence of the offer and its terms (Carlill v Carbolic, MacRobertson Miller v Commissioner of State Taxation). UNLITERAL: A contract in which the offeree accepts the contract by performing their side of the bargain. By the time of acceptance, the offeree has performed obligations and the burden falls on the offeror. Only the offeree is ever under a contractual obligation. • BILATERAL: When both parties have an exchange of promises and still have to perform their obligations. The promise must be made in return for doing the act – must be a quid pro quo between the offeree’s act and the offeror’s promise (Australian Woollen Mills Pty Ltd v • Cth). Must identify valid consideration and an intention to create legal obligations. An offer lasts until: o Specified in the offer or will end at the expiration of a reasonable period of time which depends on circumstances (Farmers Mercantile Union & Chaff Mills v Coade). o Revoked before acceptance and offeree had prior notice (Dickinson v Dodds). Offeror not normally bound by promise to keep offer open for a period of time, unless embodied in a deed or supported by consideration, e.g. an option (Goldsbrough Mort & Co Ltd v Quinn). If made to the whole world, the offeror must use appropriate means to communicate the revocation of the offer to all potential offerees (Mobil Oil v Wellcome International). o Rejected. Can be express/ inferred by offeree’s actions inconsistent with intention to accept, e.g. making a counteroffer (Stephenson, Jacques & Co v McLean). o Non-occurrence of a condition makes acceptance ineffective and causes the offer to lapse (Meehan v Jones; Financings Ltd v Stimson). o A party dies before acceptance. If the offeror dies, the offeree may accept the offer at any time prior to the receipt of notice of death (Fong v Cilli). lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES B. Acceptance Acceptance is an unqualified assent to the terms of an offer. • • • Acceptance occurs where the offeree (acceptor) communicates to the offeror whether expressly or by his conduct that s/he is willing to enter into a legally binding agreement with the offeror on the exact same terms put forward by the offeror. Any variation is a counteroffer, and constitutes rejection of the first. There are two main approaches to acceptance in which it may be inferred. a. Objectively – considers external manifestations of consent, disregarding offeree’s state of mind: Empirnall Holdings b. Subjective – Assumes that there is no contract without consensus by both parties. The favoured approach is objective (Taylor v Johnson). 1. Acceptance must be communicated to the Offeror a. Silence cannot amount to acceptance and the offeror may prescribe a particular mode of acceptance: Felthouse v Brindley (1862) b. Offeror can waive need to communicate acceptance such as in a unilateral contract: Carbolic Smoke Ball c. Silence in conjunction with other circs may be acceptable: Empirnall Holdings v Machon Paull (1988) d. If no method stipulated, any effective method will suffice 2. Must be unconditional (exact same terms as offer): Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-O Corp 3. Method of acceptance can be stipulated: Carbolic Smoke Ball, Brinkibon Ltd v Stahag Stahl 4. Implied from the offeree’s conduct; • Acceptance is determined objectively: Empirnall Holdings v Machon Paull (1988) 5. Only an offeree can accept the offer: R v Clarke (1927) 6. Postal Acceptance Rule: Snail Mail • Historic difficulties, mail by horse cart • The postal acceptance rule is an exception to the rule that acceptance must first be communicated to the offeror to be effective. Where the parties contemplate acceptance by post, acceptance will be complete as soon as the letter is properly posted (Brinkibon Ltd v Stahag Stahl). If after properly posting a letter it fails to arrive, the posting of the acceptance is nevertheless effective so long as the rule applies (Adams v Lindsell). Still effective if ‘lost in the mail’. • Applies where the parties must have contemplated that the acceptance might be sent by post (Henthorn v Fraser) 7. Postal Acceptance Rule: Electronic • In the case of instantaneous communications such as telex, facsimile or email the general rule is that acceptance is not complete until it is received (Brinkibon Ltd v Stahag Stahl). The provisions of the ETA 2000 (NSW) apply to email communications generally and have an impact upon issues concerning writing, signature and time and place of and dispatch and receipt of the email (see [2.310]-[2.320]). p.113 s13A (2) can be notifications without reading. lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES C. Consideration Consideration is what is given in exchange for a promise and concerns the enforcement of promises. Only a person who has given consideration for the other party’s promise may enforce a contract. • The promisor makes a promise to the promisee to do something or refrain from doing something. If the promisee wants to enforce that promise of the promisor, they must be able to demonstrate that they have paid for the promise – this is consideration (Beaton v • • McDivitt). BILATERAL – two promisors; each party’s promise is consideration for the other’s. UNILATERAL – only one promisor. An agreement that is not supported by consideration on both sides can be said to be nudum pactum (naked agreement) and carries the idea that the agreement is unenforceable. 1. Benefit/Detriment Requirement • Promisee must incur a detriment/ confer a benefit on the Promisor • Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co v Selfridge & Co Ltd 2. Bargain Requirement • Benefit/detriment must be given in return for a promise: Quid Pro Quo • Currie v Misa (1875) • Conditional gift – Promise to pay someone if they perform an act; not give rise to a contract. SUFFICIENCY RULE: Consideration need not be ‘adequate’ but must be ‘real’ 1. Consideration can be ‘nominal’: Chappell & Co Ltd v Nestle Co Ltd 2. Past Consideration is not good consideration: Roscorla v Thomas 3. Consideration cannot be Illusory or vague: Placer Development Ltd v Cth 4. Performing existing public duties is not good considerations: Collins v Godefroy 5. Performing Existing Contractual Duties is not good Consideration: promisor gets nothing more than which they are entitled (Wigan v Edwards; Stilk v Myrick). However, if the promisee promises to do something that exceeds the existing contractual duty, then this may be good consideration (Hartley v Ponsonby). Cases of Williams v Roffey Bros and Nicholls, Musemeci v Winadell and Re Selectmove suggest that the law is moving away from this rule. Where the promisor obtains an additional benefit from the promisee's continuing performance even though the promisee does no more that already bound to do, this may be good consideration. 6. Part Payment of a Debt is insufficient • The rule in Pinnel's Case (3.130) is that payment of a lesser sum on the due day for payment is no satisfaction of the whole debt because the agreement to accept a lesser sum is not supported by any consideration. The payer does not give the payee anything to which the payee was not already entitled (Foakes v Beer). However, the presence of something extra, provided it has some value, may change this result. 7. Compromise a Claim/Forbearance to Sue: If the promisor asserts that they are not bound to perform obligations under existing contract, or that they have a cause of action under contract, then the promise given by way of a bona fide compromise of that dispute may be good consideration: Wigan v Edwards 8. Only parties who gave consideration can enforce the contract: Coulls v Bagot’s Executor and Trustee Co Ltd lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES D. Capacity Minors • • • The general rule at common law is that a contract made by a minor is voidable. A contract is valid if it is for the supply of necessaries and beneficial contracts of service. A voidable contract created by the minor is binding until repudiated, or is non-binding and becomes binding in nature when it is ratified by the minor themselves. Mental Disability A contract is voidable at the option of a party who, as a result of mental disorder, is unable to understand the nature of the contract being made. The withdrawing party must prove: (a) That they were suffering from such a disability The question is whether the party seeking to avoid the contract was incapable of ‘understanding the general nature of what he is doing in his participation.’ It is not essential that the resulting contract be unfair: Gibbons v Wright (b) That the other party was, or ought to have been, aware of it. Capacity to buy/sell, transfer/acquire is regulated by statute concerning capacity. Necessaries – goods suitable to the condition in life of such person, and to the person’s actual requirements at the time of the sale and delivery – a question of both fact and law. Intoxication Defendant must prove that at the time of contract, they were so intoxicated that they did not understand what they were doing and the other party know/ought to have been aware: Moulton v Camroux . A contract under this may be repudiated/ratified within reasonable time of regaining sobriety. . The degree of intoxication determines contractual capacity. . If a person is not affected to such an extent, the remedy may still exist under unconscionability: Blomley v Ryan (1956) lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES E. Intention • • • • Both parties to the contract must manifest an intention to be legally bound (Australian Woollen Mills). The presence of this intention is determined objectively based on an inference from conduct. The analysis is highly factual/objective and by the reasonable person standard; courts will look to the surrounding circumstances, including actions and statements of each party, to determine the objective manifestation of their intention: Ermogenous v Greek Orthodox Community of SA An agreement can only be enforceable if the parties intended by that agreement to create legal relations. This is tested objectively by the reasonable person standard and requires consideration of various factors including: o Closeness of the relationship between the parties; o Surrounding circumstances; o Nature of the agreement (such as preliminary agreements); o Involvement of commercial interests; and o Seriousness of consequences of acting on the promise. In the interests of certainty and predictability, the law has developed presumptions in relation to the intentions of the parties to an agreement: o Commercial agreements are presumed to create legal relations - Banque Brussels Lambert SA v Australian National Industries (1989) o Agreements made in a domestic or social context are presumed to not create legal relations - Todd v Nicol [1957]. An agreement relating to substantial matters, such as employment or the sale of property, may be intended to attract legal consequences even when it is made with a relative. o Government and an individual: implementation of govt policy may lead a govt to reach an agreement with a particular individual to provide some assistance. The fact that the individual is providing something in return does not necessarily mean that the parties intend to make a contract. o Where parties reach a preliminary agreement, the question may arise whether the parties intend to be bound immediately, or not until sometime in the future when the parties have finalised some outstanding issues or recorded their agreement in a more formal manner. Three possible interpretations of a subject to contract clause are established by Masters v Cameron: 1. The parties intend to be bound immediately, but propose to restate the terms in a form which is fuller or more precise, but not different in effect. 2. The parties have agreed on all the terms of their bargain, and do not intend to vary those terms, but have made performance conditional upon the execution of a formal document. There is a binding contract whereby parties are bound to bring the formal document into existence 3. The parties do not intend to make a binding agreement at all unless and until they execute a formal contract, in which case, the terms of the agreement are not intended to have any binding effect. Parties are not contractually bound in any way until a formal document is actually signed; consider estoppel argument. lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES F. Certainty Agreement between the parties must be certain and complete. Although there may appear to be offer and acceptance, there might in fact be no concluded agreement capable of being enforced because the terms are uncertain, the agreement is incomplete or a contractual promise illusory. • A contract must be sufficiently certain and complete to be valid and enforceable. This means, all essential terms must be finalised (or method stipulated to enable terms to be calculated) and parties know their rights and obligations: Whitlock v Brew (1968) 1. The contract must be sufficiently complete. An incomplete agreement is one where crucial details have been omitted. Courts will not draft a contract where the parties have failed to stipulate the terms: Whitlock v Brew 2. The contract must be sufficiently certain and clear that parties understand their obligations and rights. When trying to determine the meaning of the language used, it is important to distinguish between obscurity and lack of meaning: Council of the Upper Hunter County District v Australian Chilling and Freezing Co. Uncertainty and vagueness will only invalidate where the courts cannot reasonably ascertain what the parties intended: Meehan v Jones. 3. The promise must not be illusory. A contractual promise is illusory where the performance required by the promise rests in the discretion of the promisor: Meehan v Jones; Godecke v Kirwan. Such an illusory promise is not enforceable: Placer Development Ltd v Commonwealth. • • In interpretation of contracts the courts apply the maxim ut res magis valeat quam perat (it is better for a thing to have effect than be found void) and will resolve ambiguities and fill gaps in agreements to some extent. Even though the language used is clear, the agreement might still fail because it is incomplete - the parties have omitted essential terms from their agreement (Hall v Busst). In the interests of upholding agreements, the courts might imply terms although this is somewhat problematic. An important development is the idea that a contract to negotiate in good faith may be valid even though an ‘agreement to agree’ is generally not valid: United Group Rail Services Ltd v Rail Corporation NSW. lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES Privity of Contract How does it apply? Definition: Privity of Contract is a common law rule which holds that only those parties who gave consideration under the main contract, can enforce the contract or be bound by the contract. 1. 2. 3. 4. Consideration must move from the promisee, yet need not move back to the promisor Only parties who gave consideration can enforce the contract: Coulls v Bagot’s Parties to the Contract cannot subject a 3rd party to obligations under the Contract Remedies can be problematic: Coulls v Bagot’s • The privity of contract rule states that only parties to a contract are legally bound by the contract and are entitled to enforce it – Trident General Insurance v Mc Niece Bros Pty There tend to be two major instances where the issue of privity arises: - Where a party to a contract attempts to confer a benefit on a third party, not a party to the contract. - Where a party to a contract seeks to impose a restriction on a third party, not a party to the contract. • How can we circumvent it? 1. DIRECT: A enters into a contract with B. C is affected by B’s conduct. A sues B directly or C tells A to sue B. 2. AGENCY: Agent- person who is authorised to contract on behalf of another. The principal is bound by the contract even though he/she may not be a signatory to the contract. 3. ASSIGNMENT (NOVATION): The right to assign is restricted if the right was personal to the promissee/assignor (Pacific Brands Sport & Leisure v Underworks Pty Ltd). Novation may be more effective (Ashton v Aus Cruising). 4. TRUST: relationship whereby property is held by one party for the benefit of another. Claims might also be possible under estoppel or unjust enrichment (Trident) (Deane J reasoning). 5. STATUTORY PROVISIONS: Govt may legislate to alter impact of common law in certain situations. 6. HIMILAYA CLAUSES Himalaya clauses are clauses that seek to exclude or limit liability of the party to the contract or anyone acting through or under that party. 7. ESTOPPEL: Third party can directly sue party of the contract they are not a part of based on reliance: Trident. This is an equitable remedy and therefore is at the discretion of the courts. 8. UNJUST ENRICHMENT The equitable basis of restitution is the concept of ‘unjust enrichment’. That is, the defendant has to restore the object or benefit to the plaintiff because otherwise, the keeping of the object or benefit would unjustly enrich the defendant. lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES Express Terms • Additional express terms may be added by oral evidence unless excluded by the parole evidence rule. If not excluded, must be clear that the pre-contractual statements are terms. These statements may amount to puffs, mere representations, collateral contracts or terms: State Rail Authority of NSW v Heath Outdoor Pty Ltd. Neither puffs nor representations have contractual force; may be remedies available independently of contract. 1) Whether pre-contractual statements should form part of the main agreement? 2) If yes, how should the statement be classified? - Puffery (Result: No remedy) - “Mere” Representation (Result: No remedy) - Warranty (Result: Damages possible) - Collateral Contract (Result: Damages/ Termination) - Term under the Contract (Result: Damages/ Termination) 3) If the contract is written, does the Parole Evidence Rule apply? Typically four methods for incorporating terms: 1. By Signature: L’Estrange v Graucob Ltd 2. By Notice: Oceanic Sun Line Special Shipping Co v Fay 3. By accepting an offer made in a ticket (ticket cases): Parker v South Eastern Railway Co 4. By a course of dealings: Rinaldi & Patroni v Precision Mouldings • Traditionally, the parol evidence rule operates to exclude proof of contractual terms by oral evidence in relation to written contracts (Goss v Lord Nugent). To circumvent the rule: i. Ask the question: is the contract wholly written or partly written and partly oral? Then you can incorporate extrinsic evidence, by looking and words, language and context. Entirety clause. ii. Factual Matrix: Does not add new terms, but modifies existing terms to resolve ambiguity. iii. Collateral/Side agreement: Yes, written document, but these pre-contractual statements become a collateral contract and thus enforceable. • A statement that amounts to a term of a contract is 'promissory' in nature. It is an undertaking or guarantee of particular legal duties and obligations under the contract. If a term is breached, the wronged party is entitled to a remedy for breach of contract. Mere representations are not intended to be promissory and redress may be limited if false. Whether or not a particular statement are terms or representations, is determined objectively: JJ Savage & Sons. Words that come across as opinion are less likely to be determined as terms e.g. I would estimate…- JJ Savage v Blakeney lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES Implied Terms Implied terms are terms which the parties failed to address when entering into the contract. Objective test by the court to determine whether those terms should be implied into the contract. • Courts can imply terms into a Contract where: - The parties intended for those terms to be included - Terms were accidentally left out - Contract was badly drafted - Intention of the parties thus critical • Courts will NOT imply terms where: - The term was deliberately excluded - Implied terms will conflict with the express terms When are terms implied? • Common law recognises three classes of implied term: 1. Terms implied in FACT: Term to be implied to address a missing fact in the case - Formal Contracts: Presumption NOT to imply terms - Informal Contracts: Presumption to imply terms to make the contract workable 2. Terms implied by LAW: Such terms are implied because of the nature of the contract itself – the same terms have been implied in previous contracts: Liverpool City Council v Irwin 3. Terms implied by CUSTOM: Comparable industry standard In appropriate cases, a term may be implied into a contract by reason of established mercantile usage or professional practice in the market. Parties are regarded as having contracted on the basis that the particular custom or usage is applicable and the term is implied in accordance with that custom or usage. There are four tests to be satisfied before a term will be implied on this basis (Con-Stan Industries Pty Ltd v Norwich Winterthur Ltd). lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES Performance and Breach, Termination for Breach of a Condition, Failure of a Contingent Condition; Termination by Agreement, Repudiation, Frustration and Time Stipulations • A contract can be brought to an end prematurely due to: 1. Termination for Breach (Condition, Warranty or Intermediate Term) 2. Failure of a Contingent Condition - Contract is subject to prior fulfilment of a condition precedent 3. Termination by Agreement: By an Express Clause 4. Termination by Repudiation:“I refuse to perform further under this Contract” 5. Frustration, e.g. One party dies, fire, war breaks out and trade the party becomes illegal. 6. Termination due to Delay Terms - Breach Condition Intermediate Warranty • • • • • • • Right to damages Yes Yes Yes Right of Termination Yes Yes (if serious consequences) No Broadly, a 'condition' is a major term and a warranty is a minor term of the contract. Even if the parties do not describe a particular term as a 'condition' a court may construe a term as a condition, objective test of intentions, if it is an essential term of the contract. Similarly, a term described in the contract as a condition may in fact be a warranty. Intermediate term: Breach was serious enough to deprive the party of ‘substantially the whole benefit… under the contract’ (Ankar) Repudiation: Occurs where one party to the contract, indicates by their words/ conduct, that they are no longer willing or able to perform their obligations under the contract (Carr v JA Berriman P/L). Objective assessment of the repudiating party’s unwillingness/inability to be bound by the contract (DTR Nominees P/L v Mona Homes). To amount to repudiation, the absence of willingness or ability to perform must relate to: - The whole of the contract; or - To a condition of the contract; or - Be 'fundamental' to the contract - The Progressive Mailing House P/L v Tabali P/L (1985) Frustration: unforeseen and faultless event occurs, which discharges the parties from their performance under the contract, because it has made performance physically/commercially impossible; OR radically different from that envisaged by the agreement (Codelfa Construction v SRA). Rights and liabilities that accrued prior to the time of the frustrating event remain in place, but the parties will be discharged from most future obligations. If time is of the essence, then the time stipulation acts as a term that can be breached. If not of the essence, then it is the equivalent of a warranty and the court’s requirement is performance within a reasonable time. Difference between the two is determined by the intention of the parties through their words, conduct and context. A time stipulation in a contract is breached by late performance. The time stipulation may be expressly stated or it may be fixed by reference to an event. Where the contract does not specify a time, the contractual obligation must be performed within a reasonable time. lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES Effect of Repudiation/Breach Following a Repudiation/Breach (of a Condition), the innocent party must ELECT: Option 1 ACCEPT the Repudiation/Breach: Results in Termination of the Contract Both parties are relieved from further performance. Prevents the offending party from retracting the Repudiation. Certain rights remain intact e.g. Accrued rights (eg payment for work done up to the point of Termination, Arbitration Clauses (p.613). Option 2 Reject the Repudiation/Breach: Results in Affirmation of the Contract (keep alive) If the aggrieved (innocent) party affirms the contract, he ignores the offending party’s repudiation/ breach and the contract remains afoot. Aggrieved party may choose to continue to perform under the contract, unless clearly pointless to do so. Where the aggrieved party chooses to continue to perform, his obligations under the contract remain effective – meaning, the offending party can utilise any breaches by the innocent party: Bowes v Chaleyer (p.611). Once affirmed, the innocent party loses the right to terminate the contract for the anticipated breach Restrictions on Right to Terminate (1) Readiness and Willingness (p 615) - Aggrieved (innocent) party cannot terminate for breach/repudiation if they were not ready/willing to perform under the contract (Foran v Wight, p.618) (2) Affirmation (p.620 top) - Innocent party cannot do acts which are inconsistent with AFFIRMATION. Extension of time does NOT necessarily amount to affirmation of the Contract – Classed as a ‘Conditional Waiver’ – Giving party in breach more time to perform the obligation in question and avoid having to Terminate – Tropical Traders Ltd v Goonan (p 623) (3) Unreasonable delay to elect to Terminate (p 623) - Innocent party has reasonable time to elect. Objective assessment of any prejudice caused to the offending party in delaying to elect (e.g. knowledge that offending party is subject to deadlines from subcontractors) (4) Doctrine of Estoppel (p 627) - Innocent party may be prevented from relying on their strict legal right to terminate IF s/he led the offending party to believe that the contract would NOT be terminated… thus causing the offending party to act to his own detriment by continuing performance under the Contract: Legione v Hateley; W & R Pty Ltd v Birdseye lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES Vitiating Factors: Duress, Undue Influence, Misleading and Deceptive Conduct • • • • • • Duress: Where one of the parties, in procuring the making of a contract or obtaining a payment of money, has brought pressure to bear on the other party, in the form of threats. The focus of our class is economic duress - pressure that is a threat to another's economic wellbeing (Williams v Roffey Bros). There are two elements to this action: o Some form of economic pressure has induced the contract (Crescendo Management P/L v Westpac Banking Corp); and o The pressure is illegitimate and/or unconscionable commercial or economic pressure (Universe Tankships of Monrovia v International Transport Workers Federation). The focus is the nature of the pressure not the overbearing of the will. The onus lies upon the person asserting the pressure. If proved, the onus shifts to the person applying the pressure. Undue Influence: Where a party, by virtue of reliance and confidence in the defendant, suffers from impaired judgement as to her or his own best interests. Main remedy is recession. Plaintiff must prove that a relationship of influence existed, characterised by the ascendancy of one party over the other. Defendant must rebut this presumption by proving that the contract (or gift) was not the result of abuse of influence but was entered into only after full free and informed thought: (Westmelton (Vic) v Archer and Schulman) Misleading and Deceptive Conduct: [Elements in notes] lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES Vitiating Factors: Unconscionability • Conduct which is against good conscience/ manifestly unfair. Occurs where one party, the stronger party, takes unconscionable advantage of a party burdened with a particular disability (the weaker party), to gain a contractual advantage: CBA v Amadio Unconscionability is a well understood equitable doctrine. It involves a party who suffers from some special disability or is placed in some special situation of disadvantage and an ‘unconscionable’ taking advantage of that disability/ disadvantage by another. The doctrine does not apply simply because one party has made a poor bargain. Elements (Taken from CBA v Amadio): (1) Weaker party suffers from a disability (special disadvantage): – CBA v Amadio – Blomley v Ryan (2) Stronger party knows (or ought to know) about that disability - Louth v Diprose (3) Stronger party takes unfair and unconscionable advantage of that disability to secure an unfair bargain and a benefit – Bridgewater v Leahy • Remedy- Recission lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES Vitiating Factors: Misrepresentation • • • Misrepresentation is defined as a false, statement of fact, made by the representor, that induces the other party (representee) to enter into the Contract and which may; or may not become a term of the contract. Can be innocent, fraudulent or negligent. There are common law causes of action for misrepresentation. ACL s18 also provides statutory protection against a broader category of behaviour called misleading and deceptive conduct, which includes misrepresentation. Only covers misleading and deceptive conduct by corporations in trade and commerce for consumer contracts of less than $40K so the common law and equity are still relevant to those circumstances not covered by the legislation. Innocent Misrepresentation (p.711) – Honest, yet mistaken belief in the truth of the statement – At Common Law: No cause of action/ remedy – Example: Oscar Chess v Williams (1948 model Morris) – In Equity: Representor (guilty party) cannot get Specific Performance (Contract thus unenforceable) – Remedy: o EQUITY: Innocent party can rescind the Contract if parties can be restored to pre-contractual position o Statutory rights of compensation in the event of rescission lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES ELEMENTS (1) False statement of FACT – Positive act is required… thus not ‘mere silence’ (Caveat Emptor) – However, see exceptions – RULE: Pufferies, opinions or predictions are NOT fact based – Smith v Land & House Property Corp; Fitzpatrick v Michel, Public Trustee v Taylor (2) Statement was aimed at the party ultimately misled – Not third persons who heard the statement via the grapevine (3) Reliance and Inducement – RULE: Statement aims to; and actually induces the contract (Nicholas v Thompson) – RULE: Does not need to be the sole inducement, sufficient to show ‘statement materially contributed (Edgington v Fitzmaurice) – RULE: A wasted opportunity to investigate truth does not defeat claim (Redgrave v Hurd) lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES Estoppel An estoppel is an equitable tool that essentially prevents or stops the promisor from asserting their strict legal rights. PE prevents the assertion of strict legal rights in circumstances where it would be unjust/unconscionable; it may be used as a sword or shield • • • • • 1. Representation: Unequivocal promise/assertion by the representor (Legione v Hateley) 2. Assumption: Relying party adopts an assumption based on the representation. 3. Inducement: Which induces the innocent party to act; OR Acquiescence: Representor fails to prevent the innocent party from acting on the representation 4. Detrimental eeliance: Party has changed their position in reliance on that promise or representation (Beaton v McDivitt). Detriment will be suffered by the innocent party (Mobil Oil v Wellcome) [The following not always required] 5. Reasonableness: Was it reasonable for the innocent party to rely on the representation? 6. Unconscionability: If the representor is permitted to deny the making of the representation (Waltons v Maher) 7. Knowledge: Representor knows/ought to know that the innocent party will suffer detriment May be available where no contract exists Estoppel by conduct – inconsistent conduct that leads to harm as a result of reliance on that conduct. A [common law] estoppel by representation arises where one party (representor) leads another (relying party) to adopt an assumption of fact (e.g. “I have signed the contract..”, and by relying on that, the relying party suffers a detriment. An [equitable] estoppel is an equitable tool that prevents (estoppes) a party from denying a state of affairs exists. Equitable estoppel includes: o Promissory estoppel (a reliance on future conduct e.g. “I will sign the contract”). o Proprietary estoppel (to do with property) Estoppel may be used as a sword or shield. As a sword it can be used to enforce a positive statement or representation relied upon. As a shield it may be employed as a defence to a promisor’s right to enforce his or her strict legal right. lOMoAR cPSD| 4666708 CONTRACT LAW TEMPLATES Remedies