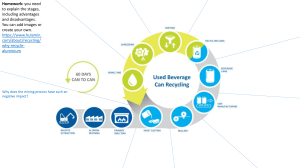

The Industrialization of China: How Industrialization and its Energy Use Contributed to Pollution and the Development of Renewable Energy as a Solution Cara Kita Writing 39C: The Question of Sustainability November 14, 2020 1 I. Introduction China has long been infamous for its heavy air pollution, so thick that it is visible to the naked eye. Its dense smog is the culmination of a variety of factors, including manufacturing plants and vehicular emissions, and it is evident that China has a severe air and energy problem.1 With the massive burning of fossil fuels and low-level environmental regulations, China’s rapid advancement from an agricultural country to an industrialized nation was not without consequence, and only recently has China started to counter this problem. The government not only increased regulations and control of substance emission, but also intensified their research and support of renewable, sustainable energy. Although China contains one of the world’s largest populations and possesses several of the most polluted cities in the world,2 their strenuous efforts to improve the environment and the air quality has met significant progress, allowing China to come closer to its goal of carbon neutrality by 2060.3 This essay explores China’s long journey from an agricultural to an industry-based country, and recounts the detriments of industrialization and its energy use even as it modernized the people by drawing from research in economics, environmental science, and historical analysis. Possible solutions to its extensive Mason F. Ye, “4.2 Causes and Consequences of Air Pollution in Beijing, China,” in Environmental ScienceBites, ed. Kylienne A. Clark, Travis R. Shaul, and Brian H. Lower (Columbus: The Ohio State University, 2018), https://ohiostate.pressbooks.pub/sciencebites/chapter/causes-and-consequences-of-air-pollutionin-beijing-china/. 1 “World’s most polluted cities 2019 (PM2.5),” IQAir, https://www.iqair.com/us/worldmost-polluted-cities. 2 Somini Sengupta, “China, in Pointed Message to U.S., Tightens Its Climate Targets,” New York Times, last modified October 05, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/22/climate/china-emissions.html. 3 2 problems with pollution are noted and analyzed as the current development and implementation of sustainable and renewable energy by China is described. II. Industrialization of China: From Agriculture to Industry Industrialization never really took off in China until the 1950s, when Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party took control. In 1953, they initiated the First Five-Year Plan with the intent to rapidly industrialize and develop its economy. Heavily influenced by the Soviet Union, they incorporated the practice of heavy industry, which included steel and coal production, into their economy and introduced collective ownership, allowing the government greater control over food prices and distribution.4 Subsequent Five-Year Plans shared similar goals, seeking to advance the technology and industry as well as to implement a socialist system and improve the overall condition of the country. This was a drastic change for China, for up to that point, industrialization was practically nonexistent, with only a handful of outdated factories.5 As summarized by John Joseph Puthenkalam, a professor in economics, the Five-Year Plans were dedicated to increasing both industrial and agricultural output and readjusting and improving upon flaws and issues discovered throughout the development of the economy.6 As new Five-Year Plans were created, a major change occurred about 30 years later through the actions of Deng Xiaoping. Up to that point, every aspect of industrial production had Rebecca Cairns and Jennifer Llewellyn, “The First Five Year Plan,” Alpha History, September 24, 2019, https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/first-five-year-plan/. 4 Cai Qibi, “Chinese Industry: A Journey of 70 Years,” China Today, April 30, 2019, http://www.chinatoday.com.cn/ctenglish/2018/hotspots/70y/journey/201909/t20190927_800179 742.html. 5 John Joseph Puthenkalam, “Emerging China’s Economic Visions during the Five Year Plans and the Evolution of the Doctrine of ‘the Scientific Concept of Development,’” Semantic Scholar, (2009): 30-33. 6 3 been stringently controlled by the Chinese government.7 Production goals, prices, and allocation of resources were all determined by the state, and foreign trade was minimal in hopes of creating a self-sufficient economy. This led to low outputs and low quality, as workers were only fixated on meeting production goals, and thus low economic performance and poor product production.8 In 1979, China began to transition away from state-controlled enterprises, moving towards a more market-based economy where the forces of supply and demand influenced production and prices rather than the government, allowing the manufacturers a small degree of autonomy in deciding the mechanics of their production.9 In agriculture, household responsibility systems were created and implemented. Instead of collective farming, where a large group of different individuals were grouped and assigned a harvest goal, individual households were responsible for fulfilling a certain quota of crops, with the promise that any extra harvest could be kept, enabling them to receive some extra income. This led to a substantial increase in food and production.10 Additionally, China opened up to foreign investments and trade, a stark contrast to its previous closed economy. This allowed new businesses to grow and develop as well as an Wayne M. Morrison, “China’s Economic Rise: History, Trends, Challenges, and Implications for the United States,” Congressional Research Service, last modified June 25, 2019, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/RL33534.html. 7 Karen Jingrong Lin et al. “State-owned enterprises in China: A review of 40 years of research and practice,” China Journal of Accounting Research 13, no. 1 (March 2020): 35-36. 8 9 Lin et al., 37. Justin Yifu Lin, “The Household Responsibility System in China’s Agricultural Reform: A Theoretical and Empirical Study,” Economic Development and Cultural Change 36, no. 3 (April 1988): 201. 10 4 increased exchange of technology and knowledge.11 Certain cities were designated as Special Economic Zones (SEZs), which allowed easier access to possible foreign investors with the possibility of tax incentives and a large pool of available workers.12 These exceptions led to rapid economic growth for the cities, making them even more attractive to businesses and investments, both foreign and domestic, and as illustrated in Figure 1, the number of SEZs has only continued to increase, having demonstrated immense success with the cities’ rapid modernization and development.13 Although the SEZs may have reaped enormous economic benefits, they were also criticized for their lax environmental regulations, allowing the surrounding air and water to be polluted with carbon emissions as well as toxic wastes and chemicals.14 This is demonstrated in Shenzhen, China, one of China’s first established SEZs. Upon a study of the surface water quality from 1991 to 2008, the Shenzhen Environmental Protection Bureau found a correlation in increasing water pollution with industry development.15 Additionally, air pollution levels increased with the construction of even more coal-powered factories, creating more carbon and sulfur emissions and further worsening the air quality. Shigeo Kobayashi, Jia Baobo, and Junya Sano, “The ‘Three Reforms’ in China: Progress and Outlook,” Japan Research Institute, September 1999, https://www.jri.co.jp/english/periodical/rim/1999/RIMe199904threereforms/. 11 Bret Crane et al. “China’s special economic zones: an analysis of policy to reduce regional disparities,” Regional Studies, Regional Science 5, no. 1 (2018): 101. 12 Jean-Paul Rodrigue, “China’s Special Economic Zones” in The Geography of Transport Systems Fifth Edition (New York: Routledge, 2020), https://transportgeography.org/?page_id=4103. 13 Benjamin J. Richardson, “Is East Asia Industrializing Too Quickly? Environmental Regulation in Its Special Economic Zones,” Pacific Basin Law Journal 22, no. 1 (2004): 170-71. 14 Yi Chen et al. “Water quality changes in the world’s first special economic zone, Shenzhen, China,” Water Resources Research 47, no. 11 (2011), doi: 10.1029/2011WR010491. 15 5 Figure 1: China’s Special Economic Zones (SEZs) The introduction of foreign countries and business into China stimulated its economy and improved its reputation and standing in the global world. More and more industries came to China to grow their business, wanting to take advantage of the tax exemptions and the available land and factories. Additionally, the establishment of factories and manufacturing plants in China was far more profitable for a variety of reasons: China contained an immense amount of workers willing to work at extremely low wages, they had extremely lax labor and environmental regulations, and they had abundant resources.16 With such a large number of people willing to Qin Chen, “Inkstone Explains: How did China become the factory of the world?” Inkstone, October 6, 2020, https://www.inkstonenews.com/business/inkstone-explains-how-didchina-become-factory-world/article/3103429. 16 6 work for a barely-living wage and little to no labor laws, factories in China could easily take advantage of the workers and squeeze the maximum possible production out of them. Little consideration was placed on safety regulations and equipment, and any workplace injuries or deaths were swept under the rug, with little to no repercussions.17 Additionally, employees could be forced to work inhumane hours and in dangerous conditions, and if they opted out, there were hundreds of other Chinese people willing to take their place. Not only did the cheap cost of human labor play a role, but extremely lenient environmental regulations further encouraged manufacturers to plant their roots in China. It was convenient to situate factories in places like China, where environmentally friendly regulations were practically nonexistent as they did not need to exert extra time and money to implement procedures to minimize and mitigate the environmental damages.18 The few environmental regulations that existed were not enforced. Consequently, many factories base themselves in China for the saved costs, showing little regard for the potential pollution their machinery and production may generate.19 This enables them to dump toxins and waste into the surrounding land or nearby rivers instead of proper clean-up procedures and harm the health of the locals and environment without the fear of facing repercussions.20 More than 60% of groundwater resources in large cities are polluted and more Peter Navarro, “The ‘China Price’ and Weapons of Mass Production,” in The Coming China Wars: Where They Will Be Fought and How They Can Be Won (FT Press, 2007), https://www.informit.com/articles/article.aspx?p=683056. 17 Jianguo Liu and Jared Diamond, “China’s environment in a globalizing world,” Nature 435 (2005): 1184. 18 Spyridon Stavropoulos, Ronald Wall, and Yuanze Xu, “Environmental regulations and industrial competitiveness: evidence from China,” Applied Economics 50, no. 12 (2018): 1378. 19 Kenneth Rapoza, “China’s Weak Environmental Laws Won’t Last Forever,” Forbes, February 23, 2012, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2012/02/23/chinas-weakenvironmental-laws-wont-last-forever/?sh=5975e01a7119. 20 7 than 25% of the major rivers in China are harmful to humans.21 In addition to affecting their health, it has also caused extreme harm to the surrounding land, rendering them useless for farming and crops.22 With the application of coal and petroleum as energy sources, the multitude of operating factories increasingly fill the air with CO2 and SO2 discharges, and further worsen China’s environment.23 Inefficient and polluting technology further exacerbate the carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels, releasing more toxins than necessary into the air.24 These many factors have heavily influenced other nations to profit off of China and its people to their detriment, and this has culminated in a wide range of environmental problems. III. Pollution and Possible Solutions Although China’s economy and industry may have flourished, their great advances came at a cost. Air pollution has become a severe and deadly problem and industrialization is the major contributor.25 Many of the factories in China use older machinery, and to power such equipment requires a prodigious amount of coal burning. Additionally, China contains many coal-based power plants that continue to be in use, providing for a growing population of over a billion people as illustrated in Figure 2, and the amount of energy burned from coal has increased Mehran Idris Khan and Yen-Chiang Chang, “Environmental Challenges and Current Practices in China — A Thorough Analysis,” Sustainability 10, no. 7 (2018), doi: 10.3390/su10072547. 21 22 Khan and Chang. 23 Liu, Jianguo and Jared Diamond, “China’s environment in a globalizing world,” 1180. 24 Liu, Jianguo and Jared Diamond, 1180. 25 Khan and Chang, “Environmental Challenges and Practices.” 8 per year.26 Figure 3 depicts the different sources of electricity used in China starting from 1990 up to 2015, with coal making up over 75% of the electricity generated, and growing in usage as time passes. Figure 2: Population of China from 1960 to 2015 in Millions Figure 3: Annual electricity generation in China, history and projection 1990-2040 “Mapped: The world’s coal power plants,” Carbon Brief, March 26, 2020, https://www.carbonbrief.org/mapped-worlds-coal-power-plants. 26 9 Consumption of coal releases pollutants like carbon dioxide (CO2) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions.27 Carbon dioxide is a commonly known greenhouse gas, contributing to global warming and climate change as it traps heat in our atmosphere.28 Sulfur dioxide, on the other hand, is harmful to both the environment and humans. It can cause trouble breathing and harm the respiratory system, and also makes up particulate matter (PM2.5), which are deadly and small particles that can cause problems to your lungs and heart.29 SO2 can also contribute to acid rain, which can kill animals and trees.30 China’s air quality is so severe that over 700,000 to 2.2 million premature as well as a variety of different health problems are attributed to the toxic gases released by coal.31 Coal is so essential to China that it takes up over half of its energy consumption, but its use of petroleum in relation to vehicles also significantly contributes to the air pollution. Previously, little emphasis was placed on the quality of fuel and their standards for oil was limited. They were focused more on minimizing costs and convenience of production than health and environmental wellbeing. Thus, the fuel would contain comparatively more sulfur than other Keith Bradsher and David Barboza, “Pollution From Chinese Coal Casts a Global Shadow,” New York Times, June 11, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/11/business/worldbusiness/11chinacoal.html. 27 “Carbon Dioxide,” University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, https://scied.ucar.edu/carbon-dioxide. 28 “Sulfur Dioxide Basics,” United States Environmental Protection Agency, https://www.epa.gov/so2-pollution/sulfur-dioxide-basics. 29 30 “Sulfur Dioxide Basics.” Robert B. Finkelman and Linwei Tian, “The health impacts of coal use in China,” International Geology Review 60, no. 5-6 (2018): 580. 31 10 countries and when used, would pollute more per amount of energy burned.32 With the addition of increased population growth and increased vehicle sales, the emissions of vehicles compounded itself and became an even more serious problem in environmental pollution, creating and releasing more CO2 and SO2 and further concentrating the smog. Figure 4 shows the increase in car ownership in China as a whole as well as Beijing, one of the major cities of China. As seen in Figure 5, the increasing contribution of oil to carbon emissions has steadily increased from 1960 to 2018. China’s rapid population growth and its intense industrialization led to an increase in energy consumption, and their reliance on fossil fuels further exacerbated their air pollution, creating a permanent cloud of smog in their urban cities, and this has encouraged them to formulate new forms and methods of energy. Figure 4: Car sales in millions of units and car ownership in units per 100 urban households in China Jin Wang et al. “Vehicle emission and atmospheric pollution in China: problems, progress, and prospects,” PeerJ 7 (2019), doi: 10.7717/peerj.6932. 32 11 Figure 5: Annual Fossil CO2 Emissions in China Renewable energy is not a new concept; there are windmills, solar panels and hydroelectric dams, all naturally replenishing with low greenhouse gas emissions. However, they are unable to produce nearly as much energy and electricity as fossil fuels do, and not nearly as easily. Thus, China is striving to develop its own form of renewable energy that is both sustainable and productive enough to provide for the country and minimize its carbon footprint. With the passing of the Renewable Energy Law in 2005, China signaled its commitment towards renewable energy. The new law “requires power grid operators to purchase resources from registered renewable energy producers” and offers financial incentives to encourage renewable energy projects.33 This made the use of renewable energy more attractive, as energy distributors “China Passes Renewable Energy Law,” Renewable Energy World, March 9, 2005, https://www.renewableenergyworld.com/2005/03/09/china-passes-renewable-energy-law23531/#gref. 33 12 were obligated to pay for a form of energy with little to no carbon footprint, practically guaranteeing some form of revenue, and thus the use of renewable energy sources has increased. Wind energy, biomass energy, and solar energy are some of the possible alternative energy sources, but each contains its own drawbacks.34 Wind turbines are costly, and there is no guarantee that it will produce a consistent output due to its reliance on the wind. Additionally, it takes up a large amount of land with its surrounding environment damaged by the turbines.35 Biomass releases comparatively far less air pollutants than fossil fuels, but despite its minimal emissions, it also produces far less energy, making it an inefficient fuel source.36 Solar energy is a huge presence in China, with the world’s largest solar capacity of over 100,000 gigawatts and as the world’s largest manufacturer of solar panel technology.37 It has been used for a wide variety of purposes, from heating water and buildings to creating electricity for general usage.38 Despite its benefits, it is difficult to utilize solar energy to its full potential. As solar farms cover a large area of land, they are generally located in less populated areas. Thus, it takes extra effort Zhenling Liu, “China’s strategy for the development of renewable energies,” Energy Sources, Part B: Economics, Planning, and Policy 12, no. 11 (2017): 971-72. 34 Mohammad Hasan Balali et al. “An overview of the environmental, economic, and material developments of the solar and wind sources coupled with the energy storage systems," International Journal of Energy Research 41, no. 14 (2017): 1951-52. 35 36 Liu, “China’s strategy for the development of renewable energies,” 973. 37 Chris Baraniuk, "How China’s giant solar farms are transforming world energy," BBC News, September 4, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20180822-why-china-istransforming-the-worlds-solar-energy. Zhi-Sheng Li et al. “Application and development of solar energy in building industry and its prospects in China,” Energy Policy 35, no. 8 (August 2007): 4122. 38 13 to deliver the produced electricity for the people to use.39 Furthermore, solar panels last about only 25 years, and upon its expiry date, a bunch of waste and chemicals will be created and left behind, unable to be easily recycled.40 Furthermore, the manufacturing of solar panels is a lengthy, complex process and involves a variety of different materials, making solar panels a costly venture. Although solar energy seems abundant and appears to be the ultimate solution to green energy, it does not provide a sustainable substitute for coal and oil due to cost and land limitations as well as future long-term consequences. Hence, the need to develop and discover more efficient sources of renewable energy is critical, preventing the fast-paced development of climate change and keeping the atmosphere at a manageable level, leading China to invest billions of dollars in renewable energy projects.41 IV. Conclusion China has come a long way since the Chinese Communist Party took power and created the People’s Republic of China. From an agricultural country to an industrial global power, China has witnessed the most drastic and rapid change in a country. Moreover, when industry came to the forefront and the environment was damaged in favor of business and economy, China adapted once more to remedy this problem, investing heavily in favor of moving from a coal-fueled industry to increasing development of renewable energy and preventing the Chris Baraniuk, “Future Energy: China leads world in solar power production,” BBC News, June 21, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-40341833. 39 Stephen Chen, “China’s ageing solar panels are going to be a big environmental problem,” South China Morning Post, July 30, 2017, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/2104162/chinas-ageing-solar-panels-aregoing-be-big-environmental-problem. 40 Jocelyn Timperley, “China leading on world’s clean energy investment, says report,” Carbon Brief, January 9, 2018, https://www.carbonbrief.org/china-leading-worlds-clean-energyinvestment-says-report. 41 14 continued deterioration and degradation of the environment. Although fossil fuels still make up a fundamental portion of energy consumption, China’s renewed efforts to find alternative energy offers a promising future in a more sustainable and environmentally friendly energy. As people continue to innovate and create, we must understand how it came to this point, and discover how to mitigate and minimize the costs of manufacturing and create a better future for the world. 15 Bibliography Balali, Mohammad Hasan, Narjes Nouri, Emad Omrani, Adel Nasiri, and Wilkistar Otieno. “An overview of the environmental, economic, and material developments of the solar and wind sources coupled with the energy storage systems.” International Journal of Energy Research 41, no. 14 (2017): 1948-1962. Baraniuk, Chris. “Future Energy: China leads world in solar power production.” BBC News, June 21, 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-40341833. Baraniuk, Chris. “How China’s giant solar farms are transforming world energy.” BBC Future, September 4, 2018. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20180822-why-china-istransforming-the-worlds-solar-energy. Bhandari, Bibek and Nicole Lim. “The Dark Side of China’s Solar Boom.” Sixth Tone: Fresh voices from today’s China.” Deep Tones, July 17, 2018. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1002631/the-dark-side-of-chinas-solar-boom-. Bradsher, Keith and David Barboza. “Pollution From Chinese Coal Casts a Global Shadow.” New York Times, June 11, 2006. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/11/business/worldbusiness/11chinacoal.html. “Carbon Dioxide.” UCAR Center for Science Education. https://scied.ucar.edu/carbon-dioxide. Cairns, Rebecca and Jennifer Llewellyn. “The First Five Year Plan.” Alpha History, September 24, 2019. https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/first-five-year-plan/. Chen, Qin. “Inkstone Explains: How did China become the factory of the world?” Inkstone, October 6, 2020. https://www.inkstonenews.com/business/inkstone-explains-how-didchina-become-factory-world/article/3103429. Chen, Stephen. “China’s ageing solar panels are going to be a big environmental problem.” South China Morning Post, July 30, 2017. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/2104162/chinas-ageing-solar-panelsare-going-be-big-environmental-problem. Chen, Yi, Zhao Zhang, Shiqiang Du, Peijun Shi, Fulu Tao, and Martin Doyle. “Water quality changes in the world’s first special economic zone, Shenzhen, China.” Water Resources Research 47, no. 11 (November 15, 2011). doi: 10.1029/2011WR010491. “China Passes Renewable Energy Law.” Renewable Energy World, March 9, 2005. https://www.renewableenergyworld.com/2005/03/09/china-passes-renewable-energylaw-23531/#gref. Chow, Gregory C. “Economic Reform and Growth in China.” Annals of Economics and Finance 5 (May 2004): 127-152. 16 Crane, Bret, Chad Albrecht, Kristopher McKay Duffin and Conan Albrecht. “China’s special economic zones: an analysis of policy to reduce regional disparities.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 5, no. 1 (2018): 98-107. Er-Rafia, Fatima-Zohra. “How did China Become the World’s Second Economic Power?” Rising Powers in Global Governance, September 17, 2018. https://risingpowersproject.com/how-did-china-become-the-worlds-second-economicpower/. Finkelman, Robert B. and Linwei Tian. “The health impacts of coal use in China.” International Geology Review 60, no. 5-6 (2018): 579-589. Khan, Mehran Idris and Yen-Chiang Chang. “Environmental Challenges and Current Practices in China—A Thorough Analysis.” Sustainability 10, no. 7 (2018): 2547. Kobayashi, Shigeo, Jia Baobo and Junya Sano. “The ‘Three Reforms’ in China: Progress and Outlook.” Japan Research Institute, September 1999. https://www.jri.co.jp/english/periodical/rim/1999/RIMe199904threereforms/. Korsbakken, Jan Ivar, Robbie Andrew, and Glen Peters. “Guest post: China’s CO2 emissions grew slower than expected in 2018.” Clear on Climate. Carbon Brief, March 5, 2019. https://www.carbonbrief.org/guest-post-chinas-co2-emissions-grew-slower-thanexpected-in-2018. Li, Zhi-Sheng, Guo-Qiang Zhang, Dong-Mei Li, Jin Zhou, Li-Juan Li, and Li-Xin Li. “Application and development of solar energy in building industry and its prospects in China.” Energy Policy 35, no. 8 (August 2007): 4121-4127. Lin, Justin Yifu. “The Household Responsibility System in China’s Agricultural Reform: A Theoretical and Empirical Study.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 36, no. 3 (1988): 199-224. Lin, Karen Jingrong, Xiaoyan Lu, Junsheng Zhang, and Ying Zheng. “State-owned enterprises in China: A review of 40 years of research and practice.” China Journal of Accounting Research 13, no. 1 (March 2020): 31-55. Liu, Jianguo and Jared Diamond. “China’s environment in a globalizing world.” Nature 435 (2005): 1179-1186. Liu, Jiayue and Jing Xie. “Environmental Regulation, Technological Innovation, and Export Competitiveness: An Empirical Study Based on China’s Manufacturing Industry.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 4 (February 2020): 1427. 17 Liu, Li-qun, Zhi-xin Wang, Hua-qiang Zhang, and Ying-cheng Xue. “Solar energy development in China — A review.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 14, no. 1 (January 2010): 301-311. Liu, Zhenling. “China’s strategy for the development of renewable energies.” Energy Sources, Part B: Economics, Planning, and Policy 12, no. 11 (2017): 971-975. Mack, Lauren. “Chinese History: First Five-Year Plan (1953-57).” ThoughtCo, last modified December 9, 2019. https://www.thoughtco.com/chinese-history-first-five-year-plan1953-57-688002. “Mapped: The world’s coal power plants.” Carbon Brief, March 26, 2020. https://www.carbonbrief.org/mapped-worlds-coal-power-plants. Morrison, Wayne M. “China’s Economic Rise: History, Trends, Challenges, and Implications for the United States.” Every CRS Report. Congressional Research Service, last modified June 25, 2019. https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/RL33534.html. Navarro, Peter. “The ‘China Price’ and Weapons of Mass Production.” In The Coming China Wars: Where They Will Be Fought and How They Can Be Won. FT Press, 2007. https://www.informit.com/articles/article.aspx?p=683056. Puthenkalam, John Joseph. “Emerging China’s Economic Visions during the Five Year Plans and the Evolution of the Doctrine of ‘the Scientific Concept of Development.’” Semantic Scholar, (2009): 29-45. Prime, Penelope B. “What China’s ‘export machine’ can teach Trump about globalization.” The Conversation, November 27, 2016. https://theconversation.com/what-chinas-exportmachine-can-teach-trump-about-globalization-63608. Qibi, Cai. “Chinese Industry: A Journey of 70 Years.” China Today, April 30, 2019. http://www.chinatoday.com.cn/ctenglish/2018/hotspots/70y/journey/201909/t20190927_ 800179742.html. Rapoza, Kenneth. “China’s Weak Environmental Laws Won’t Last Forever.” Forbes, February 23, 2012. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2012/02/23/chinas-weakenvironmental-laws-wont-last-forever/?sh=5975e01a7119. Richardson, Benjamin J. “Is East Asia Industrializing Too Quickly? Environmental Regulation in Its Special Economic Zones.” Pacific Basin Law Journal 22, no. 1 (2004): 155-174. Rodrigue, Jean-Paul. “China’s Special Economic Zones.” In The Geography of Transport Systems Fifth Edition. New York: Routledge, 2020. https://transportgeography.org/?page_id=4103. 18 Sengupta, Somini. “China, in Pointed Message to U.S., Tightens Its Climate Targets.” New York Times, last modified October 5, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/22/climate/china-emissions.html. Standaert, Michael. “Why China’s Renewable Energy Transition Is Losing Momentum.” Yale Environment 360. Yale School of the Environment, September 26, 2019. https://e360.yale.edu/features/why-chinas-renewable-energy-transition-is-losingmomentum. Stavropoulos, Spyridon, Ronald Wall and Yuanze Xu. “Environmental regulations and industrial competitiveness: evidence from China.” Applied Economics 50, no. 12 (2018): 13781394. “Sulfur Dioxide Basics.” EPA, United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/so2-pollution/sulfur-dioxide-basics. Timperley, Jocelyn. “China leading on world’s clean energy investment, says report.” Carbon Brief, January 9, 2018. https://www.carbonbrief.org/china-leading-worlds-clean-energyinvestment-says-report. The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Special economic zone.” Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica, September 20, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/topic/special-economiczone. Wang, Jin, Qiuxia Wu, Juan Liu, Hong Yang, Meiling Yin, Shili Chen, Peiyu Guo, Jiamin Ren, Xuwen Luo, Wensheng Linghu, and Qiong Huang. “Vehicle emission and atmospheric pollution in China: problems, progress, and prospects.” PeerJ 7, (2019). doi: 10.7717/peerj.6932. West, Bonnie. “Chinese coal-fired electricity generation expected to flatten as mix shfits to renewables.” Today In Energy. Energy Information Administration, September 27, 2017. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=33092. “World’s most polluted cities 2019 (PM2.5).” IQAir. https://www.iqair.com/us/world-mostpolluted-cities. Ye, Mason F. “4.2 Causes and Consequences of Air Pollution in Beijing, China.” In Environmental ScienceBites, edited by Kylienne A. Clark, Travis R. Shaul, and Brian H. Lower. Columbus: The Ohio State University, 2018. https://ohiostate.pressbooks.pub/sciencebites/chapter/causes-and-consequences-of-airpollution-in-beijing-china/.