Uploaded by

pittoolafferty

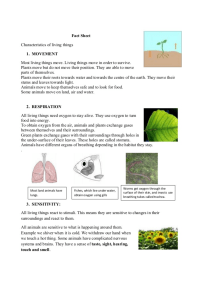

Fitness Nutrition: A Comprehensive Coursebook