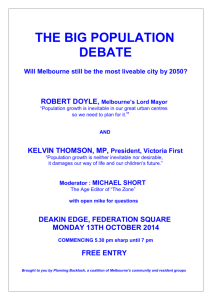

4. Results and Discussion 4.1. Case Study 1: “Measuring housing and transportation affordability: A case study of Melbourne, Australia”. (2017), Journal of Transport Geography, 65, 134–146. This study primarily studied the association between the cost of housing and transportation in terms of geography and the drawbacks of solely consideration on housing affordability for families in Melbourne. According to this case study, housing was an important part of urban planning and family decision-making. At the same time, housing for an ordinary family is a large part of their wealth. Housing has a unique dual role. It is not only an investment opportunity, but also a kind of durable commodity that produces consumer services. However, scholars generally believed that the recent real estate boom in some organizations for economic cooperation and development, including Australia, has led to a significant decline in housing supply capacity. As a result, the differences between different regions have widened and various social and economic problems have arisen. The calculation of the comprehensive burden of housing and transportation is affected by many factors, such as the choice of rent, the source of housing, the location of housing, the mode of transportation, the distance and the purpose of traffic, etc. However, due to the difficulty of data acquisition, it is difficult to separate the influence of different factors on the cost, so this paper simplifies the calculation method. Based on the calculation method of housing and transportation affordability index, combined with the current situation and data acquisition degree, the calculation of comprehensive burden is adjusted and revised. In this study, the calculation is divided into two different types. One is the calculation of individual housing and transportation affordability. In this method, housing cost can be divided into two types: second-hand housing and rental housing. The second is the calculation of housing and transportation affordability based on the family original unit method, which excludes the influence of individual and family choices on housing and transportation affordability, and only considers the influence of different locations on housing and transportation affordability. Housing prices in 30 Australian cities are listed as "seriously unaffordable" by the international report on affordable housing. Sydney is the third most expensive housing market in the world, while Melbourne is the seventh. Rising house prices have led to a sharp rise in the cost of living. Australia has experienced an unprecedented mining boom in the past few years. During this period, foreign capital poured in and the Australian monetary system expanded. The loose credit environment has led to a rise in real estate prices and a boom in consumption, leading to a surge of more than 50% in Australian housing prices in recent years. In addition, Australia has implemented a relatively loose immigration policy in the past few years, absorbing a large number of immigrants, increasing the rigid demand for housing and constantly pushing up house prices. Figure 1, the Estimated Probability Distribution of Housing and Transportation Affordability in Melbourne from the Case Study The housing and transportation cost estimates are derived from public sources, including the Victoria government open data catalog and ABS, such as the 2011 Australian census data, and a comprehensive survey of Victoria's tourism and activities. The data are detailed in the median weekly rental, the average number of vehicles per household, and the share of travel modes. The data of vehicle operation cost, interest rate, median property price and bus fare are all obtained from other open channels in Victoria. According to official data, Melbourne's weighted average real estate price growth rate in 2018 was 9.6 per cent, compared with 3 % and 2.3 % in Victoria's public and private sectors in the same period. In recent years, the growth rate of real estate price has significantly hindered the income growth in the same period (Saberi et al, 2017). In 2018, APRA implemented a number of strategies to slow down real estate price growth. Specific measures include the requirement that loan institutions reduce the growth rate of loans to investors to less than 10%, and raise the capital adequacy requirements. This study screened out the statistical areas with zero median mortgage repayment or rent from the data. If the median is zero in the data of these regions, it may be caused by many reasons. These reasons include being bound by parliamentary District regulations that prohibit people from living in such areas. Sample data may also be limited in areas where most homes are completely occupied by owners without collateral. Therefore, this study applies a similar filtering logic to the data of Vista whose average transportation time or distance is zero. According to this case study, Melbourne's median household weekly income ranges widely and varies widely between regions. The number of figures can be from $577 / week to $2288 / week. The average income of Melbourne's families is estimated at $1425 a week. According to the 2018 census, the population density of areas close to CBD is much higher than in the suburbs. However, most of the housing in the eastern and Southeast suburbs has very high chromium prices. This makes the weekly housing cost for households in the region between $255 and $967. The housing in the surrounding Melbourne area is relatively cheap. The cost of housing for most families in the region ranges from $183 to $450 a week. This phenomenon shows the spatial analysis results of the use of traditional housing affordability measures. The median of family income in SA2 was used as the denominator of affordability index. This can partly represent the housing pressures of existing residents in Melbourne. The denominator is the median weekly household income in Melbourne, which represents housing supply capacity, especially for first-time buyers. It can be seen that most of the Melbourne metropolitan areas can be divided into alternative areas by traditional measures, without distinguishing whether middle-sized or regional income is used (Ley et al, 2020). For example, in the case of the Mornington Peninsula area. Although housing costs are significantly higher than the average of Melbourne, the average household income in the region is lower due to the high concentration of retired residents. Hence, the current housing supply does not seem to meet the needs of local residents. Figure 2, Cloud Map from the Case Study (Saberi et al, 2017) According to the results of this study, the cost of living of residents decreases with the distance from the central urban area and the central urban area. However, the consumption level of Melbourne varies greatly from region to region. As mentioned earlier, Melbourne has different regional characteristics. The differences of regional characteristics of Melbourne are shown in various aspects, such as income, population, employment opportunities, geographical location, public infrastructure and services. The results show that the housing cost of 61.0% of the metropolitan area of Melbourne is higher than the income ratio of 25%. Therefore, if only the cost of housing is considered, the area can be classified as alternative. If the median regional income is used, the ratio is 61.2%. In terms of the spatial characteristics of transportation and commuting costs, the estimated transportation costs of households in this study range from $120 to $388 per week. This value will vary in different regions in Melbourne. Residents close to Melbourne's CBD have lower transportation costs (Saberi et al, 2017). This is because the geographical advantage in the central area makes it easier for these residents to reach various transportation infrastructures and destinations. However, with the increase of the distance between Melbourne residents' residence and CBD, the transportation cost of families is also gradually increasing. This makes the distribution of transportation costs show the opposite relationship with the distribution of housing costs. The housing cost of families located in the urban center or CBD area is higher, and the transportation cost is lower, while the housing cost of families located in the urban fringe area is lower, but the transportation cost is higher. Through the case study of Melbourne, this paper proved that the traditional method of measuring housing affordability is not representative, because it ignores the cost of transportation or accessibility. These case studies adopted new data-driven methods to estimate the family transportation cost. In order to make up for the defects of the traditional measurement method, the public transport cost, the operation and ownership cost of private vehicles, and the working and non-working trips on weekdays and weekends are included in the measurement framework. The results show that living in the suburbs far away from the CBD of Melbourne metropolis does not necessarily reduce the cost of living, but the specific situation is related to the geographical location of the family. Case Study 2: “Understanding the Lived Experiences of Housing and Transport Stress in the "Affordable" Outer Ring: A Case Study of Melbourne, Australia. Urban Policy and Research”, (2021), 1–17. This paper presents data collected from 73 qualitative interviews conducted in three strategic outer suburbs of Melbourne, Australia. These findings show how to experience the combined effects of housing and transportation costs in daily life, including the choice of living and lifestyle. People have to make choices and adaptations. Housing availability is a complex analysis problem. It is considered to be highly correlated with family income, housing costs and the cost of the remaining part of standard living. In analyzing this association, assessing housing affordability is often limited by data availability and measuring the cost-of-living components. Housing affordability is usually defined and evaluated based on economic feasibility. This requires the neglect of other important factors, such as transportation or accessibility costs. Traditionally, housing affordability is measured by the ratio of housing expenditure to family income. In general, more than 30 per cent of income is used for housing costs (Smith et al, 2021). And households with incomes at the bottom of the income range of 40 percent are considered to be under housing pressure. This method is widely used in international housing policy because of its simplicity, because it only relies on some variables that are usually easy to calculate. Figure 3, Median Income of Melbourne Family (Smith et al, 2021) Taking public transportation as the travel mode of low-income families, the research on the comprehensive burden of low-income families were divided into three different scenarios, namely new house, second-hand house and rental house. The average burden levels are 154%, 105% and 47% respectively. That is to say, for low-income families, only the comprehensive burden of renting houses is affordable. For the middle-income families who choose to travel by bus, according to the conclusion, the average burden of second-hand housing and rental housing is affordable. From the perspective of spatial pattern, the comprehensive burden distribution of second-hand housing has obvious structural characteristics. From the perspective of rental housing, the comprehensive burden of the study area has basically achieved full coverage of less than 60%, and its affordability is significantly stronger than that of new and second-hand housing. Figure 4, Rising of Housing Price in Major Cities of Australia (Ley et al, 2020) The comprehensive burden of this case study shows that the areas with low housing burden and high traffic burden are also concentrated in the periphery of the city. In the main city, high housing burden and low traffic burden are the main factors, followed by high housing burden and high traffic burden. Different from the results of the original family unit method, the individualized comprehensive burden study found that low housing burden and low traffic burden areas appeared near the peripheral subway lines. The possible reason is that the accessibility calculation of the original family unit method does not consider the impact of congestion index on commuting time, and in real life, subway is less vulnerable to traffic congestion than public transport and private cars (Williams, 2020). Therefore, the individualized traffic burden research clearly reflects the impact of congestion on the traffic cost, that is, the traffic advantage of the communities along the subway is also greatly enhanced. In addition, the difference between the original family unit method and the individual method is also reflected in the new development area. The study of family unit method shows that the new town of Melbourne belongs to the area of low housing price and high transportation cost, while the individual study finds that this area belongs to the area of low housing price and low transportation cost. This may be because the newly developed areas have relatively perfect functional support, which makes it more likely for residents to get employment nearby, resulting in lower transportation costs. Case Study 3: “Examining building age, rental housing and price filtering for affordability in Melbourne, Australia”. (2021) Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 58(4), 809–825. This paper mainly studies the relationship between the housing affordability and the housing age and surrounding transportation facilities in Melbourne. Governments around the world have responded to the challenge of housing affordability through supply side solutions. Proponents of these methods often cite the concept of "filtering effect", arguing that over time, new supply will naturally flow to low-income families, thereby increasing their affordability. This study explores the characteristics of affordable housing in Melbourne, Australia, and analyzes the impact of residence age on rental cost. In this paper, the hedonic rent model is used to determine the nonlinear relationship between construction age and rent, which reflects the premium of historical real estate in inner Melbourne. This case also makes cluster analysis on the rental list, and measures the affordability according to the cluster. The results of this case study challenge the concept of filtering. It found that most of the contemporary affordable housing was initially built as social housing or for low-income families in the 1960s and 1970s. The case thinks that filtering is unnatural in this case, but reflects the historical government expenditure and past construction choices. Figure 5, Amount of Housing Possessed by Families in Each Intervals of Ages in Victoria (Bryant, 2014) As this case study indicated, housing costs tended to fall with distance from the city core, but the lower housing prices outside the city are often to balance the relatively high transportation costs. Meanwhile, this case concluded that the rapid rise in land prices in the heart of the capital had greatly offset the decline in housing values. As a result, there is little filtered evidence in the suburbs and the central suburbs. The growing value of the land has encouraged redevelopment, demolition or construction of poorly located or very small dwellings for niche markets. Due to the lack of public transport infrastructure in suburban areas outside the city, families in urban fringe areas are more dependent on the use of private vehicles. This dependence on the use of private vehicles is usually related to the number of vehicles owned by each household, travel time and travel distance. In Australia, transportation costs are estimated to be the second or third highest category of average household expenditure. Therefore, the traditional location affordability measure ignoring transportation costs can not reflect the actual cost of housing. Figure 6, Results about the Conditions of the Affordable Housing in Melbourne from Case Study As this case study stated, Melbourne had the largest population growth in 2013, with 4.3 million residents. Melbourne covered an area of about 10000 square kilometers, including 31 districts. In this city, the distribution of private car ownership and the use of public transport also have great spatial differences. Previous studies on real estate and traffic characteristics are based on Melbourne to explore these characteristics. Melbourne has low density residential development, different distribution of work and other activities, and a radial train network designed primarily to transport individuals from the suburbs to CBD (Palm et al, 2021). In addition, the government of Melbourne encouraged new development policies in the marginal areas of cities with low land and inconvenient traffic, and created a city environment where housing and transport demand did not match supply. As a result, the accessibility of transport and various activities in Melbourne's internal areas is higher than that in the external areas (Raynor, 2021). In the peripheral areas with underdeveloped public transport infrastructure, the ownership of private cars is also significantly higher among Melbourne residents. In terms of the spatial distribution of housing pressure, the area with the greatest housing pressure is Melbourne city center. Based on the study of housing affordability shown in Figure 6, occupation and living location, this paper found that families living and working in the city center bear more housing pressure than those working in the city but living in other areas. This means that the housing burden of the central city aggravates the income and spatial polarization phenomenon, thus reducing the housing choice of low-income groups. The lack of suitable affordable housing means that many employees either pay a high proportion of their income on housing or live far away from their workplace. The result is that most of the people living in the city center and high cost of living areas are young people, rich people and families without children. But whether this kind of spatial polarization city can ensure the sustainable development of the area is a question. 4.7. Discussion Through the three case studies, it is indicated that as house prices continue to rise, down payment, stamp duty and various fees rise rapidly. As the population continues to grow, the situation will only get worse if we do not act. House prices have always been a high concern topic in Australia. In recent years, especially in Sydney, Melbourne and other big cities, the soaring housing prices have forced the Australian government to intervene. The Australian government has taken measures such as increasing the stamp duty and limiting the speculation of international buyers, which has made the house price maintain a relatively stable situation since 2017 (Bryant, 2017). Although external demand has further pushed up house prices, low interest rates are also the main driving force of Australian house prices. The low mortgage rate brought by the Bank of Australia's loose policy stance is likely to stimulate the further growth of house prices. And high prices increase the risk of over inflation in the real estate market. The increase in house prices exceeds the growth of household disposable income. The longer the time is, the greater the chance of bubble formation and expansion (Lee, 2020). Economic imbalance is followed by congestion and worsening commuting conditions in Melbourne, which is bound to become a huge restriction of urban development. It can be seen from this that, in addition to making great efforts to renovate the real estate market, the top priority for Victoria is to solve the problem of unbalanced regional development. After all, social development problems are closely linked, and controlling the real estate market can only get twice the result with half the effort. Restrictive policies on housing supply, such as urban integration and urbanization, have been implemented in Australia for many years. These policies, as well as complex local and state policy processes, are believed to be responsible for the rise in housing costs. Recently, some national planning systems have introduced a series of reforms, resulting in a surge in the number of housing approvals. At the same time, banks have introduced low interest rates, and investors' demand for housing investment has also increased. However, there is little evidence that deregulation can improve efficiency (Han et al, 2021). On the contrary, the effective way to improve efficiency is to adopt strategies such as effective housing ownership supported by the state. Some scholars have discussed and proposed the possibility of introducing and adjusting the Singapore model (McLaren, 2016), that is, most people own their own houses through public housing. At the same time, the government has imposed restrictions on the use of private cars. In this way, people will be more motivated to take public transport when they travel or commute to their destinations. The reform of housing security and urban planning in Australia has been discussed comprehensively by many scholars. They have determined some current policies and planning countermeasures for housing security. These policies include encouraging the development of housing, ensuring rental housing and building social and public housing (Lehoux et al, 2018). The existing policies mainly focus on increasing the demand of first-time home buyers and investors, while reducing the obstacles to new housing development. Although there are more and more literatures about housing security and housing security related policies, few current urban policies recognize the importance of transportation cost in housing security planning (Ley et al, 2020). Previous studies have recognized the link between transportation and housing affordability, and this paper will further strengthen this link empirically (Johnson, 2018). Australia's major central cities have gradually reduced public investment in local transport infrastructure to encourage more public-private partnerships. Moreover, the government overemphasized the method of user payment. It also means that infrastructure is no longer free or compulsory to pay for urban development (Williams, 2020). This is believed to lead to rising house prices and improved transport accessibility. Some of the strategies being considered by large cities in Australia include integrating transport planning with land use planning, solving housing accommodation problems by mixing land use and urban density around transport hubs, and promoting urban growth along existing and planned railways, such as the new plan of railways proposed by the Australian Government in 2021. These case studies demonstrated the close relationship between transportation and housing capacity. Based on this close connection, local and state governments suggest that housing planning take into account both the accessibility of transport infrastructure and the development of new residential areas. In addition, some scholars have studied the relationship between traffic accessibility and property value (Lee, 2020). The research showed that over time, the relationship is not as strong as previously thought. Therefore, improving traffic accessibility will not necessarily lead to long-term growth of real estate value. This is especially obvious in areas with mature transportation network. In general, the findings highlight the need to address transport convenience needs and housing supply to meet future housing supply. This also supports the view of some previous studies that improving transport infrastructure can effectively increase the supply of housing and help people reduce their daily commuting time. 5. Conclusion 5.1. Introduction In Australia, there is no unified definition of housing affordability. Because there are many factors affecting housing affordability, it is difficult to define and measure it accurately. Different understanding of housing affordability will lead to different definitions. In addition, different types of families are faced with different housing affordability problems. The location fixity of housing determines its location relationship with employment place, school and other urban public service facilities, and causes corresponding transportation cost, which becomes an important part of family living expenses. The theory of urban spatial structure shows that land use and transportation are closely coupled in urban space. Residents' choice of residential location is a trade-off process between housing cost and transportation cost, which is often reflected in the relationship between the two costs. The comprehensive affordability index of housing and transportation studied in this paper provides a new perspective to measure residents' housing affordability more comprehensively. Compared with the traditional housing affordability index, this new index focuses on the regularity of housing cost and transportation cost in urban space. Therefore, it can be more accurate and closer to the real measurement of the impact of residential location choice on the level of family welfare. This is particularly important for low-income families, because many low-income people live in remote but inconvenient places for the sake of low housing prices. Only considering the housing cost will overestimate their ability to pay, but not the transportation cost of daily commuting. Melbourne buyers are forced to choose location. Public transport infrastructure is scarce in remote areas, but the burden of housing is low. The burden of housing in the central area is great, although public transportation brings great convenience and low commuting cost. Finally, the government or planning department may need to combine public transport planning with the construction of affordable housing (Raynor et al, 2021). 5.2. Main Conclusion As a result, once the transportation cost is taken into account, the living cost of the outer suburbs can hardly be reduced to an acceptable level, while the living cost of the residents near the suburbs can be significantly reduced. However, the comprehensive analysis of location affordability cannot be based only on the distribution of housing and transportation costs. Location affordability is also affected by lifestyle, neighborhood characteristics and demography in different areas. The study also investigated the spatial characteristics of new housing and transportation availability metrics. For example, the most disadvantageous areas will be concentrated in the outer suburbs of Melbourne, while the relatively good areas will also be concentrated around the city center (Saberi et al, 2017). The first case study in this paper introduced the innovative method of affordability of housing and transportation to study the comprehensive burden of housing and transportation in the central urban area of Melbourne. The generalized concept of time cost is included in the calculation of transportation cost, and the transportation cost data are obtained through accessibility analysis and Transportation Survey, that case study stated the comprehensive housing burden of Melbourne from two different aspects, excluding the influence of family choice and the tendency of actual family choice. Finally, according to the research results of comprehensive burden, the paper put forward relevant suggestions and Enlightenment from the perspective of residents and urban government (Han et al, 2021). 5.3. Recommendation There are many factors influencing housing affordability. Many studies have identified some factors related to housing affordability, such as interest rate, income level, construction cost, land supply and house price, and these factors are intertwined. At present, one of the biggest problems for low-income families is that it is difficult to find affordable and suitable housing. Sustainable housing is a residential building with energy saving, environmental protection, health and comfort and efficiency. Its core is to pay attention to the energy conservation and pollution reduction of buildings and the harmony between human and nature with the concept of sustainable development. In order to balance the burden of housing and transportation, the concept of sustainable development can be introduced into the planning of housing, because reducing the burden of transportation is closely related to the establishment of ecological travel. Paying attention to ecological benefits in housing design and construction has been widely accepted by rich families all over the world. However, the question is whether this should be made a mandatory requirement for housing for all income groups. The resulting increase in housing costs will come at the expense of smaller housing areas, fewer garages, or reduced household spending on energy, water, and travel (Obremski et al, 2019). Housing location is very important to realize sustainable economic development. In view of a series of problems caused by the extension of suburbs, the new urbanism puts forward the development mode of "public transport led development unit". Its core is to take the regional traffic station as the center, take the appropriate walking distance as the radius, design the distance from the center of the town to the edge of the town, which is only a quarter of a mile or five minutes' walk, to replace the dominant position of cars in the city. Within this radius, medium and high-density residential buildings will be built to increase the residential density of the community, from 1 residential unit per acre to 6 units. Mixed residential buildings and supporting public land, employment, business and service facilities will effectively achieve the purpose of composite function, and integrate the relationship between public transportation and land use mode from the regional macro perspective. According to the view of new urbanism, providing medium and high-density housing near transportation stations and corridors can ensure that residents can make more convenient use of public transport, thus reducing the use of private cars and reducing the cost of transportation and infrastructure. In Australia, there is no case of community organizations participating in housing development. In the United States, public participation in housing design and development has achieved good results (Squire et al, 2021). In order to improve the affordability of housing, we need to reduce the cost of housing. Therefore, in housing planning and design, housing should be built near public transport, infrastructure and community facilities, and the impact of climate and sunshine should be fully considered. Good housing design can make housing warm in winter and cool in summer, and reduce the use of energy. For example, the rational use of sunlight can increase the use of solar energy, thus replacing the use of electricity and gas. Housing design should also provide high-quality public open space to attract residents of all ages to participate in community activities. It can help reduce the cost of housing use and achieve good community interaction. In addition, in order to achieve the sustainability of housing, it is needed to provide community facilities, compact design, pedestrian friendly design and ecological housing. It can be seen that sustainable housing and affordable housing have many common characteristics. Therefore, it is possible for affordable housing to be sustainable by introducing community participation in housing design and obtaining ecological housing through government subsidies. Reference Bryant, Lyndall. (2017). Housing affordability in Australia: an empirical study of the impact of infrastructure charges. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 32(3), 559–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-016-9527-0 Bryant, Lyndall, & Eves, Chris. (2014). The link between infrastructure charges and housing affordability in Australia: where is the empirical evidence? Australian Planner, 51(4), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2013.877509 Han, Hoon, Kim, Sumin, Jin, Mee Youn, & Pettit, Chris. (2021). Providing affordable housing through urban renewal projects in Australia. International Review for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development, 9(2), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.14246/irspsd.9.2_41 Johnson, Carol. (2018). The Australian Right in the "Asian Century": Inequality and Implications for Social Democracy. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 48(4), 622–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2018.1441894 Lee, Chyi Lin, & Locke, Martin. (2020). The effectiveness of passive land value capture mechanisms in funding infrastructure. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 39(3), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPIF-072020-0084 Ley, David, Mountz, Alison, Mendez, Pablo, Lees, Loretta, Walton-Roberts, Margaret, & Helbrecht, Ilse. (2020). Housing Vancouver, 1972–2017: A personal urban geography and a professional response. The Canadian Geographer, 64(4), 438–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12663 Lehoux, Pascale, Pacifico Silva, Hudson, Pozelli Sabio, Renata, & Roncarolo, Federico. (2018). The Unexplored Contribution of Responsible Innovation in Health to Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), 10(11), 4015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114015 Ley, David. (2021). A regional growth ecology, a great wall of capital and a metropolitan housing market. Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 58(2), 297–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019895226 McLaren, J., Yeo, A., Sweet, M., (2016). Australia is facing a housing affordability crisis: is the solution to this problem the Singapore model of housing? Aust. Acc. Bus. Financ. J. 10 (4), 38–57. Obremski, Helena, & Carter, Claudia. (2019). Can self-build housing improve social sustainability within low-income groups? Town Planning Review, 90(2), 167–193. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2019.12 Palm, Matthew, Raynor, Katrina Eve, & Warren-Myers, Georgia. (2021). Examining building age, rental housing and price filtering for affordability in Melbourne, Australia. Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 58(4), 809– 825. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020927839 Raynor, Katrina, & Coenen, Lars. (2021). Business model innovation and scalability in hybrid affordable housing organisations: empirical insights and conceptual reflections from Melbourne, Australia. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-021-09836-x Ryan-Collins, Josh. (2021). Breaking the housing–finance cycle: Macroeconomic policy reforms for more affordable homes. Environment and Planning. A, 53(3), 480–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19862811 Saberi, Meead, Wu, Hongzhi, Amoh-Gyimah, Richard, Smith, Jonathan, & Arunachalam, Dharmalingam. (2017). Measuring housing and transportation affordability: A case study of Melbourne, Australia. Journal of Transport Geography, 65, 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.10.007 Sen, Suman, Charles, Michael B, & Harrison, Jennifer L. (2021). Determinants of Commute Distance in South East Queensland, Australia: Implications for Usage-based Pricing in Lower-density Urban Settings. Urban Policy and Research, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2021.1922376 Squires, Graham, Javed, Arshad, & Trinh, Hai Hong. (2021). Housing charges to fund bulk infrastructure: innovative or traditional? Regional Studies, Regional Science, 8(1), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2021.1882883 Williams, Galina, & Nikijuluw, Ruth. (2020). The economic and social benefit of coal mining: the case of regional Queensland. The Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 64(4), 1113–1132. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8489.12401 Zalejska-Jonsson, Agnieszka, Wilkinson, Sara J, & Wahlund, Richard. (2020). Willingness to Pay for Green Infrastructure in Residential Development—A Consumer Perspective. Atmosphere, 11(2), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11020152