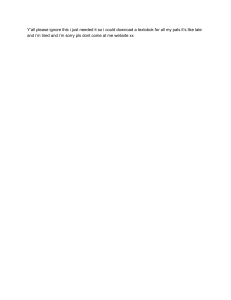

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235294249 The PALS School-Wide Positive Behaviour Support Model in Norwegian Primary Schools – Implementation and Evaluation Article in International Perspectives on Inclusive Education · May 2012 DOI: 10.1108/S1479-3636(2012)0000002006 CITATIONS READS 11 2,099 4 authors: Terje Ogden Mari-Anne Sørlie The Norwegian Center for Child Behavioral Development The Norwegian Center for Child Behavioral Development 131 PUBLICATIONS 2,122 CITATIONS 32 PUBLICATIONS 343 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Anne Arnesen University of Oslo SEE PROFILE Wilhelm Meek-Hansen 2 PUBLICATIONS 20 CITATIONS 5 PUBLICATIONS 29 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Special education View project Implementation of evidence-based programs and practices in Norway View project All content following this page was uploaded by Terje Ogden on 04 September 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. International Perspectives on Inclusive Education Emerald Book Chapter: The PALS School-Wide Positive Behaviour Support Model in Norwegian Primary Schools - Implementation and Evaluation Terje Ogden, Mari-Anne Sørlie, Anne Arnesen, Wilhelm Meek-Hansen Article information: bl is hi ng To cite this document: Terje Ogden, Mari-Anne Sørlie, Anne Arnesen, Wilhelm Meek-Hansen, (2012),"The PALS School-Wide Positive Behaviour Support Model in Norwegian Primary Schools - Implementation and Evaluation", John Visser, Harry Daniels, Ted Cole, in (ed.) Transforming Troubled Lives: Strategies and Interventions for Children with Social, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties (International Perspectives on Inclusive Education, Volume 2), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 39 - 55 Pu Permanent link to this document: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/S1479-3636(2012)0000002006 up Downloaded on: 31-05-2012 To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com d G This document has been downloaded 5 times since 2012. * ro References: This document contains references to 28 other documents al Users who downloaded this Chapter also downloaded: * )E m er Preston Green, Joseph Oluwole, (2006),"The No Child Left behind Act of 2001 and Charter Schools", Frank Brown, Richard C. Hunter, in (ed.) No Child Left Behind and other Federal Programs for Urban School Districts (Advances in Educational Administration, Volume 9), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 127 - 139 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1479-3660(06)09007-X (c James E. Lyons, (2006),"Fiscal Equity Under Title I and Non-Title I Schools in Local School Districts", Frank Brown, Richard C. Hunter, in (ed.) No Child Left Behind and other Federal Programs for Urban School Districts (Advances in Educational Administration, Volume 9), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 3 - 21 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1479-3660(06)09001-9 Hella Bel Hadj Amor, Amy Ellen Schwartz, Leanna Stiefel, (2006),"Do Good High Schools Produce Good College Students? Early Evidence from New York City", Timothy J. Gronberg, Dennis W. Jansen, in (ed.) Improving School Accountability (Advances in Applied Microeconomics, Volume 14), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 51 - 80 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0278-0984(06)14003-1 Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by Emerald Group Publishing Limited For Authors: If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service. Information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Additional help for authors is available for Emerald subscribers. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information. About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com With over forty years' experience, Emerald Group Publishing is a leading independent publisher of global research with impact in business, society, public policy and education. In total, Emerald publishes over 275 journals and more than 130 book series, as well as an extensive range of online products and services. Emerald is both COUNTER 3 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation. *Related content and download information correct at time of download. is h in g THE PALS SCHOOL-WIDE POSITIVE BEHAVIOUR SUPPORT MODEL IN NORWEGIAN PRIMARY SCHOOLS – IMPLEMENTATION AND EVALUATION ro u p Pu bl Terje Ogden, Mari-Anne Sørlie, Anne Arnesen and Wilhelm Meek-Hansen G ABSTRACT (c ) Em er al d This chapter provides an overview of a programme or rather a model used in Norwegian primary schools to meet the needs of children whose behaviour difficulties interrupt teaching and learning. In this chapter we give an overview of the PALS model and also present the general outline of a longitudinal outcome study of the school model including some information about the participating schools, staff and students. INTRODUCTION Emotional and behavioural difficulties (EBD), including rule-breaking, disruptive and acting-out behaviour are among the largest unmet challenges Transforming Troubled Lives: Strategies and Interventions for Children with Social, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties International Perspectives on Inclusive Education, Volume 2, 39–55 Copyright r 2012 by Emerald Group Publishing Limited All rights of reproduction in any form reserved ISSN: 1479-3636/doi:10.1108/S1479-3636(2012)0000002006 39 40 TERJE OGDEN ET AL. (c ) Em er al d G ro u p Pu bl is h in g in Norwegian primary schools. Children who are aggressive and violent at school are at risk for later antisocial careers, particularly if they also have academic problems (Mytton, DiGuiseppi, Gough, Taylor, & Logan, 2007). Both serious EBD and less dramatic instances of norm and rule-breaking behaviour among students are main concerns among teachers and parents in many schools. Even though the prevalence of behaviour problems is not monitored in Norwegian schools on a regular basis, the OECD PISA study ranked Norway and Greece at the bottom of the list among 29 participating countries when it came to disruption, noise and unrest in the classrooms (Kjærnslie, Lie, Olsen, Roe, & Turmo, 2004). In addition to the high prevalence of off-task behaviour, and other behaviours incompatible with learning in Norwegian classrooms, there is also a small group of students who have more serious EBD (Lindberg & Ogden, 2001; Wilson & Lipsey, 2007). The concern for the safety and well-being of other students has been one of the main reasons for excluding these high-risk students from ordinary classrooms and even schools. On the other hand, the broad political consensus on the idea of inclusive schools in Norway conveys the message that even if some students are very difficult to handle in ordinary classes, placements in special units and groups should be limited or avoided. This policy has led to an increased demand for school-based intervention strategies that might work in regular schools and classrooms. Several methods, strategies and programmes have been developed for that purpose, but the empirical support of their effectiveness is still limited (Nordahl, Gravrok, Knutsmoen, Larsen, & Rørnes, 2006). One of the promising models is the school-wide positive behaviour support (SWPBS) model which has been adapted to Norwegian primary schools and named PALS. THE PALS SCHOOL INTERVENTION MODEL PALS is the Norwegian acronym for ‘positive behaviour, supportive learning environment and interaction in school’. The model is based on the principles and procedures of the SWPBS model (Sprague & Walker, 2005) and adapted to Norwegian primary schools (grade 1–7) by Anne Arnesen and Wilhelm Meek-Hansen at the Norwegian Centre for Child Behavioural Development (NCBD) (Arnesen, Ogden, & Sørlie, 2006). Comprehensive and intensive strategies targeting serious behaviour problems are combined with positive behaviour support and preventive interventions aimed at the majority of well-behaved students. The general idea behind PALS is to replace reactive and punishing approaches to 41 The PALS SWPBS Model in Norwegian Primary Schools problem behaviour with proactive strategies which influence students through teaching and learning activities, generous support of positive behaviour and through the quality of the learning environment. THEORETICAL FOUNDATION (c ) Em er al d G ro u p Pu bl is h in g Underlying the SWPBS and the PALS school model is the idea that the ecology of cognitive and social learning influences the development of academic and social competence (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). On the micro-social level, social interaction learning model and social learning theory (Patterson, 1982) explain how children learn to control their aggression and act prosocially in a mutual learning process with their environment, including parents, siblings, peers and teachers. Difficult children and negative parenting practices initiate coercive family processes in which reciprocal learning produces socially unskilled children who become increasingly aversive in their interactions with others. At school they experience academic failure and tend to be rejected by their peers and confronted by their teachers. Rejection and failure undermine their ‘social bond’ to the school. They easily turn to students with similar problems for contact and support and start reinforcing each other’s negative behaviours (McEvoy & Welker, 2000). According to coercion theory, coercive cycles between parents and children increase the risk of children initiating similar interactions with their teachers leading to prolonged reciprocal interactions around disruptive behaviours (Forster, 2010; Nelson & Roberts, 2000; Patterson, 1982). The SWPBS model (Sprague & Walker, 2005) is consistent with coercion theory, and was particularly influential in the process of developing the Norwegian PALS model. CORE COMPONENTS The main objective of the three-tiered positive behaviour support model is to establish a positive school climate for all students and at the same time promote long-term changes in the behaviour of higher-risk students (Bradshaw, Reinke, Brown, Bevans, & Leaf, 2008). The SWPBS model aims to alter the school environments by targeting staff behaviours in order to create systems and procedures that promote positive change in student behaviour (Bradshaw, Mitchell, & Leaf, 2010). Universal prevention at level 1 addresses the whole school population with particular emphasis on reaching the 80–90% of the students with few or none behaviour problems 42 TERJE OGDEN ET AL. d G ro u p Pu bl is h in g (Muscott, Mann, & LeBrun, 2008). This primary tier involves the general idea that students are taught behavioural expectations the same way as they are taught academics (Darch & Kameenui, 2004). Consequently, behavioural expectations are defined, taught, monitored and rewarded across all arenas of the school. Additionally, a clearly defined and consistently implemented continuum of consequences for problem behaviours is established. The monitoring of the students’ social behaviour is used for planning and implementing changes in routines or practices. Secondary prevention at level 2 of behaviour support is designed for the 5–10% of students at risk for problem behaviour who barely respond to the universal prevention strategies (Muscott et al., 2008). Tertiary prevention at level 3 addresses the remaining 1–5% of high-risk students and involves individualized interventions that are based on Functional Behaviour Assessment (FBA). The interventions often include family or community collaboration, in order to prevent the emergence or continuation of more serious problem behaviour. The PBS school-wide model has been evaluated in several studies, some of which are summarized in a later section. Certain adaptation of the SWPBS model had to be made in order for the model to be implemented in Norway. er al TEN PRINCIPLES UNDERLYING THE PALS MODEL Em Based on the theories and research outlined in the previous paragraphs, 10 intervention principles underlying the PALS model might be formulated. (c ) 1. Evidence-based interventions. Evidence-based practice is based on what is considered to be the best available research knowledge about what works in order to develop positive behaviour support for all students. Norwegian PALS schools are continuously trying to implement evidencebased practices like those applied within SWPBS in organizational systems that are designed to promote the fidelity of implementation and sustainability of effects (Horner et al., 2009). 2. School-wide interventions. The school-wide approach involves all students and the whole staff and emphasizes that monitoring and interventions should target all arenas of the schools. What goes on at the classroom level shall reflect values and standards at the school level. The approach stresses the importance of consistency in the communication of norms, and common rules. Norms and expectations are filtered down the school organization from leadership to the individual student. 43 The PALS SWPBS Model in Norwegian Primary Schools (c ) Em er al d G ro u p Pu bl is h in g 3. Multi-modal interventions. Multi-modal interventions are implemented at the individual level, the classroom or group level, the school level and the system or organizational level. Interventions might target students directly or indirectly through the staff. 4. Matching interventions to the students’ risk level. A three-tiered model of assessment and intervention is differentiating between universal (primary), selected (secondary) and indicated (tertiary) interventions. The universal interventions – Tier 1. Most students are well behaved, but still they deserve a reasonable amount of praise, encouragement and rewards for complying with school rules, norms and expectations. Interventions for all students might include (a) school-wide rules and procedures for encouragement of positive student behaviour, (b) predictable consequences for problem behaviour and (c) proactive classroom management, academic support and good directions. The targeted group interventions – Tier 2. Approximately 5–10% of the student body have difficulties in coping with the expectations from teachers and peers. Among the interventions at this level are (a) additional social skills training, individually or in small groups, (b) additional academic support to individual students or as small group instruction, (c) the teaching of emotional regulation and effective problem-solving skills to teachers, (d) proactive classroom management skills for teachers and (e) increased home–school cooperation. The intensive individual interventions – Tier 3. Interventions at this level include (a) individual and multi-systemic support plan based on FBA, (b) intensive social skills training, (c) parent training and (d) behaviour management training for teachers. 5. Positive behaviour support. Positive behaviour support emphasizes the importance of communicating to the students rules and expectations about what they are expected to do (rather than what they should not do), and the systematic use of positive feedback and consequences in order to promote positive behaviour. All students are taught positively formulated rules and norms for expected behaviour which are followed up with consequent, frequent and instant positive feedback both to the students, their teachers and sometimes also their caregivers. 6. Action-oriented and skills-oriented interventions. This principle is based on the assumption that students sometimes learn more from what teacher and staff do, than from what they say. Although, increased teacher awareness and reflection is emphasized in the PALS model, it is followed by practical problem solving, planning and concrete action. Increased student and staff competence are important outcomes, and both groups 44 TERJE OGDEN ET AL. (c ) Em er al d G ro u p Pu bl is h in g are given ample opportunity through role play and experience based learning activities to rehearse and practice new skills. 7. Problems-oriented and resource-oriented interventions. Assessment of risk factors is combined with systematic attention to protective factors and resources, both in the students and in the school environment. At each school, the particular constellation of risk factors and resources is used in the planning of interventions. 8. Interventions that aim at increasing academic and social competence. Social and academic competence are mutually reinforcing, and either of the two might be the cause of the other. Students with initial reading problems develop behaviour problems, and children who enter school with behaviour problems tend gradually to struggle with school work (Morgan, Farkas, Tufis, & Sperling, 2008). Moreover, cognitive deficits, attention problems and a dysfunctional context may be common underlying causes of academic as well as social and behavioural problems in school. Consequently, both academic skill deficits and social skills deficits are targeted in an overall intervention strategy with problem students. 9. Team-based intervention approach. Most successful prevention and intervention programmes in school are based on team models in which all important groups at the school are represented, including the school leadership and the parents. Teams who are familiar with the intervention components and well trained in the implementation strategy are the link between the programme supervisor and the school staff. The school team plans and implements interventions, introduces the model to parents and staff, monitors the process and outcomes and coordinates the school-wide assessment of risk and protective factors. The teams receive monthly training and consultation from their supervisor, while the teams train the school staff on a weekly basis. 10. Interventions implemented with fidelity. All the core components of the programme model should be carried out as planned and consonant with the programme’s goals and theoretical assumptions (Wilson & Lipsey, 2007). The PALS model is implemented in each school over a period of 3 years. The first year is a planning year where universal school-wide and classroom planning occurs and the school staff receive training. During the second year, staff combines universal interventions targeting all students with selected interventions targeting at-risk students. In the third year, the school staff continues the implementation at the individual and group level, and staff adds FBA and interventions targeting the high-risk students to the programme. 45 The PALS SWPBS Model in Norwegian Primary Schools The 10 principles emphasize interventions that promote friendship, positive social relations and social bonding to school. Through the teaching and learning of necessary skills and generous doses of encouragement and rewards for participation and positive behaviour, the students learn to cope with the student role and participate in school activities. RESEARCH ON THE SWPBS MODEL (c ) Em er al d G ro u p Pu bl is h in g Most evaluations of the SWPBS model have focused on the primary prevention tier, and promising results have been demonstrated, although mostly in non-randomized studies in one or two schools or in a large group of schools. There are exceptions to this, and Bradshaw et al. (2010) studied the impact of the SWPBS model in a 5-year longitudinal randomized controlled effectiveness trial in 37 elementary schools in the United States. The school-level analyses indicated a significant reduction in student suspensions and office discipline referrals (ODRs) in the schools trained in SWPBS as compared to schools not trained in the model. Some diffusion of particular elements of the model occurred in the comparison schools, but they did not sustain these efforts over the course of the trial. In another study by Bradshaw et al. (2008), 21 schools were randomly assigned to receive training in PBS and 16 were untrained control schools. Trained schools evidenced significantly higher levels of implementation fidelity while non-trained schools showed some increases, but lagged behind trained schools on most subscales. In a third randomized study which included 30 elementary schools and used a wait-list control design, it turned out that evidence-based practices could be implemented systemically at the whole-school level (Horner et al., 2009). But the lack of pre-intervention information prohibited the establishment of causal associations between the intervention and reductions in ODRs. In a cohort of 28 early childhood education programmes and K-12 schools, the universal level of the SWPBS model was implemented with fidelity within 2 years and sustained over the course of the following year (Muscott et al., 2008). A substantial reduction in ODR and suspensions was achieved, but as in the previous study, limitations of the study design made it impossible to establish that changes in student behaviour were attributable to the SWPBS intervention. Legitimate concerns have also been raised about the reliability of using ODR measures to document the effects of the programme. Also the number of players involved in the process and the complexity of interactions among them can be problematic for ensuring consistent outcomes (Irvin, Tobin, Sprague, Sugai, & Vincent, 2004). 46 TERJE OGDEN ET AL. (c ) Em er al d G ro u p Pu bl is h in g Some studies have focused on the secondary level of interventions, and particularly on the Check In–Check out (CICO) programme, which is frequently used at this level. The results from such studies are promising, showing a reduction in problem behaviour attributable to the CICO intervention, but most of these studies have included very few students. Todd, Campbell, Meyer, and Horner (2008) included four elementary school-age boys, Hawken, MacLeod, and Rawlings (2007) did a study on 12 students, the same number of students as in Crone, Hawken, and Horner (2004) study. Moreover, in the Todd et al. (2008) study, generalization of the results were difficult because the schools programmatically also used the SWPBS system. An intervention targeting students at the tertiary level called the PreventTeach-Reinforce (PTR) model was tested in an RCT with 245 students in Grade K-8 (Iovannone et al., 2009). Preliminary results showed that the PTR group had significantly higher social skills, more academic engaged time and significantly lower problem behaviour when compared with students who received services as usual. On the downside, the study reported that most teachers discontinued implementing the interventions after problem behaviour decreased or the study was ended. The authors speculate that maybe the teachers did not view behaviour as a skill requiring continuous instruction as did reading, math or writing. As can be seen from the studies reported, there are limitations to the outcome research on the SWPBS model. First, several of the studies only evaluate one of the three levels of intervention while the possible impact of the other simultaneously implemented levels is not taken into consideration. Several of the studies have no comparison group, and some studies have a very small participant groups which makes significant conclusions and generalizations difficult. Moreover, several authors have questioned the validity of ODR as an outcome variable (Hawken et al., 2007; Muscott et al., 2008) partly because this variable may not always correlate with observed reductions in problem behaviour in the classroom (Hawken et al., 2007). In spite of the fact that SWPBS has been implemented in over 9,000 American schools (Bradshaw et al., 2010), there is still a lack of controlled effectiveness studies which document positive outcomes in regular practice (Horner et al., 2009). THE FIRST EVALUATION OF PALS The PALS school-wide intervention model in Norway was initially implemented and evaluated in a quasi-experimental design in which four intervention schools were compared to four matched neighbouring schools. 47 The PALS SWPBS Model in Norwegian Primary Schools Pu bl is h in g All comparison schools initiated some type of school improvement projects, but the interventions were different from those implemented in the PALS schools. The teachers’ assessment of student behaviour in the PALS schools showed that the percentage of low-risk students (students with one or no serious incidents reported this year) had increased from 78.5% to 86.6% from the first to the second year of implementation. The proportion of moderate-risk students (between two and five serious incidents reported this year) had decreased from 10.5% to 8.1%, and the percentage of high-risk students (six or more serious incidents reported by staff this year) from 9.5% to 5.3% (Arnesen & Ogden, 2006). Two years after the model was introduced, the PALS schools reported reduced student problem behaviour and increased social competence compared to the comparison schools (Sørlie & Ogden, 2007). The encouraging results set the stage for a largescale implementation and evaluation project with an increased number of schools and a more advanced research design. ro u p THE SECOND EVALUATION OF PALS (c ) Em er al d G In 2002 four Norwegian primary schools implemented PALS and by 2007 when the second evaluation of the PALS model was initiated, 91 schools were practicing the model. Additionally, from 2008 some schools implemented a compressed version of the model, referred to as the PALS ‘short version’. A considerable number of schools were needed in order to evaluate PALS, as school was the unit of analysis. A total of 65 schools contribute to the current study; one group of 28 schools implement the full-scale PALS model, a second group of 17 schools implement the PALS short version and a third group of 20 schools function as comparison schools. In the planning of the study, it was emphasized that (a) the number of schools should be large enough to analyse group differences between schools, (b) the participating schools should be representative of Norwegian primary schools and (c) schools in the different intervention conditions should be equivalent. STUDY DESIGN The study has a strengthened quasi-experimental design in which comparison schools are matched to the PALS schools on size and geographical location. The comparison schools were recruited from the same municipalities as the PALS schools, while the PALS short version schools were TERJE OGDEN ET AL. PALS Evaluation Timeline 2007–2012. Pu bl Fig. 1. is h in g 48 (c ) Em er al d G ro u p recruited from other municipalities. Using two rather than one comparison group increases the possibility to explore threats to the causal inference (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). In order to prevent programme contamination, schools implementing similar prevention and intervention programmes were not included in the study. Neighbouring schools to the PALS schools were, for instance, not invited. Information is collected from principals, teachers, teacher assistants, after-school personnel, students and parents. A research contact was appointed at each school, and these persons were trained and supported throughout the study by the research project staff. To evaluate the short- and long-term effects of PALS, data are collected at six time points during four successive school years (Fig. 1). A double pre-test was included in the design to help examine selection bias and attrition as sources of observed effects (Shadish et al., 2002). Adding a repeated pre-test of the same construct on consecutive occasions prior to treatment also helps reveal maturational trends, detect regression artefacts, and study testing and instrumentation effects. INTERVENTIONS AS IMPLEMENTED An external PALS coach provided training and coaching to each school’s PALS team monthly through 2 school years (2007–2009) for approximately 20 hours per year (2 hours/10 training sessions). In addition to building 49 The PALS SWPBS Model in Norwegian Primary Schools (c ) Em er al d G ro u p Pu bl is h in g leadership teams in each school from the first year of implementation, the PALS teams were provided booster sessions and sustaining implementation activities in four half-day regional or local network meetings per school year. The external coach also offered follow-up phone calls to the schools’ local PALS coach and principal between the training sessions. The PALS team was responsible for planning and monitoring the implementation at their school. They trained the school staff in using the key features and intervention components approximately 2 hours each month. The team spent a minimum of 2 hours per week on the implementation activities. Each year PALS teams and staff attended a national conference as part of the sustaining activities. The PALS team further planned and implemented a system of supports for high-risk students. Part of the team’s responsibility was to collaborate with professionals in the district’s health or child care system to develop local competencies. Evidence-based three-tiered interventions to promote positive behaviour and social competence were implemented depending on assessment of the students’ risk level. Data on discipline referrals (DR) and FBA was used to determine the level of intervention. The Universal Interventions – Tier 1: All students were taught the defined school-wide rules and expectations across all settings on a daily basis through the first 2 weeks. The staff provided systematic supervision and immediate acknowledgement and encouragement of all students. They also provided predictable responses to students’ inappropriate behaviour across all school settings. The Targeted Group Interventions – Tier 2: The students who did not profit from the tier 1 interventions were identified (typically in range of 3–5 major DRs) and provided interventions based on the particular need of the student. Schools used different interventions for targeted students based on school discipline data and available resources. Typically, elements from the First Step to Success (Golly, Sprague, Walker, Beard, & Gorham, 2000) and the behavioural education programme CICO were used to meet students’ needs for positive support and feedback more efficiently. Intensive Individual Interventions – Tier 3: For the most challenging students (typically having more than six major DRs), individual support teams were established. These teams planned, implemented, monitored and evaluated the students’ progress and response to the intervention and support. The high-risk students were provided an individualized behaviour support plan based on functional assessment. Actually, the intervention most frequently used for improving the students’ social skills was the cognitive behavioural programme Stop-Now-And-Plan (SNAP) (Augimeri, Farrington, Koegl, & Day, 2007). 50 TERJE OGDEN ET AL. THE PALS SHORT VERSION (c ) Em er al d G ro u p Pu bl is h in g Recruitment of schools to the PALS short version took place in 2008 by an open invitation to all primary schools in strategically selected urban municipalities in which no PALS or comparison schools were located. Prior to the invitation all schools were stratified into three subgroups according to school size (small, medium, large). The schools which volunteered for participation received a 30 hours practice-oriented course for the whole school staff in how to prevent and manage problem behaviour. The staff in the 17 schools in four sites (1–7 schools per site) attended four full-day courses through the school year 2008–2009. The courses took place at each of the four sites and contained all key features (components þ interventions) for implementation of the school-wide PALS model. The training sessions provided a combination of lectures, demonstration, training, coaching and ‘home-work’. The participating schools received the PALS manual as a compendium and all training materials could be downloaded from the Internet. Contrary to the full-scale PALS schools, the PALS short version schools were not offered any external coaching and implementation or technical support. Research hypotheses: The key research hypothesis for the evaluation study is that students attending the PALS schools will demonstrate fewer externalizing problems and higher social competence than students in the comparison schools. Expectations are also that the students attending the PALS schools implementing the long version will over time develop more positive behaviour compared to the comparison students. Moreover, it is expected that the interventions will be more effective at lower grade levels than at higher levels, that boys will benefit more than girls, and that students with the highest risk level will change more than students at lower risk levels. Based on the previous pilot study (Ogden, Sørlie, & Amlund-Hagen (2007), it is also expected that students with Norwegian as their second language will improve more on the social skills outcome variable than their peers. PARTICIPANTS After recruiting 65 schools for participation in the study, the characteristics of the schools, their staff and students were analysed. The distribution of small, medium and large schools in the sample correspond fairly well with the national distribution (8.4% o100 students, 39% 100–299 students, 52.6% W300 students, Statistics Norway, 2009a). In accordance with the 51 The PALS SWPBS Model in Norwegian Primary Schools (c ) Em er al d G ro u p Pu bl is h in g selection procedure, no differences between the PALS, PALS short version and comparison group were found on these variables. The number of staff participants at baseline amounted to 2,380 and the overall response rate was 81.1%. It was higher in the PALS schools (86.8%) than in the PALS short version schools (79.9%) and the lowest response rate was registered in the comparison schools (73.5%). No baseline differences were found among the groups on any of the staff indicators measured, indicating that the three groups of participating schools were comparable on these variables. The baseline descriptive data of staff corresponded well with national data in that most of the staff participants were middle aged (60% older than 35 years) and experienced teachers (86% had worked more than 5 years in school) and 8 out of 10 were female. Among the 10,681 students in 4th to 7th grade, written consent to participation was given for 8,236 and 7,761 participated in the baseline assessment, which is a 77% participation rate and 94% of those who had their parents consent to participate. According to the school principals, 5.3% had received special education the previous school year, which matches the mean national level of 5.5%. Moreover, an average of 4.5% had been referred to school psychological services and 7.6% had minority background (mainly from Pakistan, India, Somalia and Eastern Europe). The PALS short version schools as a group had a higher percentage of immigrant students than the PALS and comparison group. The principals reported the proportion of students with moderate to serious behaviour problems to be 7.8%; relatively more such students in the PALS schools (9.2%) than in the PALS short version (8.8%) and the comparison schools (4.9%). After having recruited the participant schools, two important questions were raised. The first was, as outlined above, whether the three groups of schools differed at baseline as regards school, student and staff characteristics. The second question was addressing whether the participating schools were representative of primary schools in Norway. Few group differences were found among the three groups of schools (PALS, PALS short version and Comparison) at baseline. The participant schools were compared to national averages on more than 50 learning environment variables in the national registry database for schools. Group differences were only found on eight variables. The baseline comparison led to the conclusion that there were far more similarities between the school groups than differences, and that the sample was representative of Norwegian primary schools. The recruitment procedure and research design thus seemed to reduce some known weaknesses of non-randomized studies and contributed to creating a representative sample of Norwegian primary schools and comparable groups of schools. 52 TERJE OGDEN ET AL. MEASURES G ro u p Pu bl is h in g The primary outcome variables of the evaluation study are measures of problem behaviour in school based on teacher observations. The measures ‘Problem Behaviour in the School Environment last Week’ and ‘Problem Behaviour in the Classroom last Week’ were originally developed by Grey and Sime (1989) and require teachers, assistants and after-school personnel to report how many times they have observed negative behaviour incidences during a randomly selected week. The observations take place in the classrooms or on other areas in school like in the hallways and on the playground. The third measure requires teachers to report the number of students seriously hindering learning and teaching activities in class during the present year (‘Behaviour Problematic Students in Class this Year’; Kjøbli & Sørlie, 2008; Ogden, 1998; Sørlie & Ogden, 2007). Additionally, teachers assess individual students according to selected items from the ‘Teacher’s Report Form’ (TRF: Achenbach, 1991) and from the ‘Student/ Child Problem Behaviour Scale’ (Gresham & Elliott, 1990; Sørlie & Nordahl, 1998). al d CONCLUDING COMMENTS (c ) Em er In response to the increasing demand for school-wide intervention strategies that match students’ needs and level of functioning in Norwegian schools, PALS has proved to be a good model. The model promotes school-wide social competence, positive behaviour and interaction through teaching, skills training, classroom management, monitoring, supervision and home– school collaboration. Students and staff formulate, teach and learn a set of positively formulated rules that conveys clear expectations for positive behaviour. Consistent use of encouragement and incentives contributes to the recognition of pro-social behaviour while negative behaviour is met with predictable consequences. At the school level, monitoring of student behaviour lays the foundation for the identification of problems, problem solving, planning, implementation and evaluation. The principle of matching interventions to the students’ risk level signals the blending of preventive and ameliorating interventions. The majority of students mostly abide by school rules and expectations and should be consistently complimented and rewarded for doing so. At the same time, effective strategies are needed in order to manage and reduce more serious emotional and 53 The PALS SWPBS Model in Norwegian Primary Schools Pu bl is h in g behavioural difficulties among students. Individualized positive behaviour support should be the vehicle for turning problem students around. The SWPBS model has been extensively evaluated, but there is a need of controlled effectiveness studies documenting positive outcomes in regular practice (Horner et al., 2009). In the first Norwegian evaluation of PALS, the outcomes were encouraging, but the number of schools was small (Sørlie & Ogden, 2007). The increasing number of primary schools implementing the PALS model in Norway has made it possible to recruit schools which are representative of Norwegian primary schools, to a large-scale evaluation study. In a quasi-experimental longitudinal design, the selection of schools seems to have resulted in equivalent groups of schools with more similarities than differences. Two of these groups implement the PALS model or the PALS short version programme and one group serve as a comparison group. p REFERENCES (c ) Em er al d G ro u Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR and TRF profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. Arnesen, A., & Ogden, T. (2006). Skoleomfattende kartlegging av problematferd [School-wide assessment of problem behaviour]. Spesialpedagogikk, 2, 18–29. Arnesen, A., Ogden, T., & Sørlie, M.-A. (2006). Positiv atferd og støttende læringsmiljø i skolen [Positive behaviour and supporting learning environments in school]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. Augimeri, L. K., Farrington, D. P., Koegl, C. J., & Day, D. M. (2007). Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16, 799–807. Bradshaw, C. P., Mitchell, M. M., & Leaf, P. J. (2010). Examining the effects of schoolwide positive behavioural interventions and supports on student outcomes. Results from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behaviour Interventions, 12, 133–148. Bradshaw, C. P., Reinke, W. M., Brown, L. D., Bevans, K. B., & Leaf, P. J. (2008). Implementation of school-wide positive behaviour interventions and supports (PBIS) in elementary schools: Observations from a randomized trial. Education and Treatment of Children, 31, 1–26. Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiment by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Crone, D. A., Hawken, L. S., & Horner, R. H. (2004). Responding to problem behavior in school. The behaviour education program (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. Darch, C., & Kameenui, E. (2004). Instructional classroom management: A proactive approach to behaviour management (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson-Merrill Prentice-Hall. Forster, M. (2010). When cheap is good: Cost-effective parent and teacher interventions for children with externalizing behaviour problems. Dissertation, Uppsala University, Uppsala. Golly, A., Sprague, J., Walker, H., Beard, K., & Gorham, G. (2000). The first step to success program: An analysis of outcomes with identical twins across multiple baselines. Behavior Disorders, 25, 170–182. 54 TERJE OGDEN ET AL. (c ) Em er al d G ro u p Pu bl is h in g Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (1990). Social skills rating system (Manual). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. Grey, J., & Sime, N. (1989). Findings from the national survey of teachers in England and Wales. In Elton (1989). Discipline in schools. Report of the Committee of Enquiry chaired by Lord Elton. Department of Education and Science and the Welsh Office. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office. Hawken, L. S., MacLeod, K. S., & Rawlings, L. (2007). Effects of the Behaviour Education Program (BEP) on office discipline referrals of elementary school students. Journal of Positive Behaviour Interventions, 9, 94–101. Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., Smolkowski, K., Eber, L., Nakasato, J., Todd, A. W., & Esperanza, J. (2009). A randomized wait-list controlled effectiveness trial assessing school-wide positive behaviour support in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behaviour Interventions, 11, 133–144. Iovannone, R., Greenbaum, P. E., Wang, W., Kincaid, D., Dunlap, G., & Strain, P. (2009). Randomized controlled trial of the prevent-teach-reinforce (PTR) tertiary intervention for students with problem behaviours. Journal of Emotional and Behavioural Disorders, 17, 213–225. Irvin, L. K., Tobin, T. J., Sprague, J. R., Sugai, G., & Vincent, C. G. (2004). The validity of office discipline referral measures as indices of school-wide behavioural status and effects of school-wide behavioural interventions. Journal of Positive Behaviour Interventions, 6, 131–147. Kjærnslie, M., Lie, S., Olsen, R. V., Roe, A., & Turmo, A. (2004). Rett spor eller ville veier? Norske elevers prestasjoner i matematikk, naturfag og lesning i PISA 2003. Oslo, Universitetsforlaget. Kjøbli, J., & Sørlie, M.-A. (2008). School outcomes of a community-wide intervention model aimed at preventing problem behaviour. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 49, 365–375. Lindberg, E., & Ogden, T. (2001). Elevatferd og læringsmiljø 2000 [Student behaviour and learning environment 2000]. Oslo: Læringssenteret. McEvoy, A., & Welker, R. (2000). Antiscocial behaviour, academic failure, and school climate. A critical review. Journal of Emotional and Behavioural Disorders, 8, 130–140. Morgan, P. L., Farkas, G., Tufis, P. A., & Sperling, R. A. (2008). Are reading and behaviour problems risk factors for each other? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 5, 417–436. Muscott, H. S., Mann, E. L., & LeBrun, M. R. (2008). Positive behavioural interventions and supports in New Hampshire. Effects of large-scale implementation of schoolwide positive behaviour support on student discipline and academic achievement. Journal of Positive Behaviour Interventions, 10, 190–205. Mytton, J., DiGuiseppi, C., Gough, D., Taylor, R., & Logan, S. (2007). School-based secondary prevention programmes for preventing violence (Review). Evidence-Based Child Health, 2, 814–891. Nelson, J. R., & Roberts, M. L. (2000). Ongoing reciprocal teacher-student interactions involving disruptive behaviours in general education classrooms. Journal of Emotional and Behavioural Disorders, 8, 27–37. Nordahl, T., Gravrok, Ø., Knutsmoen, H., Larsen, T. M. B., & og Rørnes, K. (2006). Forebyggende innsatser i skolen. Rapport fra forskergruppe oppnevnt av Utdanningsdirektoratet og Sosial- og helsedirektoratet om problematferd, rusforebyggende arbeid, læreren som leder og implementeringsstrategier. Oslo: Utdanningsdirektoratet. Ogden, T. (1998). Elevatferd og læringsmiljø. Læreres erfaringer med og syn på elevatferd og læringsmiljø i grunnskolen. [Student behaviour and learning environment. Teachers’ 55 The PALS SWPBS Model in Norwegian Primary Schools (c ) Em er al d G ro u p Pu bl is h in g experiences and view of student behaviour and learning environment.] Oslo: Norwegian Ministry of Education. Ogden, T., Sørlie, M.-A., & Amlund-Hagen, K. (2007). Building strength through enhancing social competence in immigrant students in primary school. A pilot study. Journal of Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 12, 105–117. Patterson, G. R. (1982). A social learning approach. Coercive family process (Vol. 3). Eugene, OR: Castalia Publishing Company. Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. Sprague, J. R., & Walker, H. M. (2005). Safe and healthy schools. Practical prevention strategies. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Sørlie, M.-A., & Nordahl, T. (1998). Problematferd i skolen. Hovedfunn, forklaringer og pedagogiske implikasjoner. [Behaviour problems in school. Main findings, explanations, and pedacogical implications]. Hovedrapport fra forskningsprosjektet ‘‘Skole- og samspillsvansker. Rapport 12a/98. Oslo: Norsk institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring. Sørlie, M.-A., & Ogden, T. (2007). Immediate impacts of PALS: A school-wide multilevel programme targeting behaviour problems in elementary school. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 51, 471–492. Todd, A. W., Campbell, A. L., Meyer, G. G., & Horner, R. H. (2008). The effects of targeted intervention to reduce problem behaviours. Elementary school implementation of check in–check out. Journal of Positive Behaviour Interventions, 10, 46–55. Wilson, S. J., & Lipsey, M. W. (2007). School based interventions for aggressive and disruptive behaviour: Update of a meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33(Suppl. 2), 130–143. View publication stats