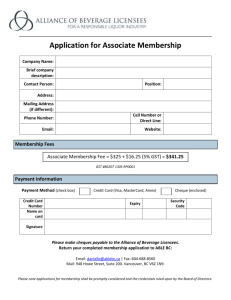

2020 NATIONAL GST INTENSIVE ONLINE “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud National Division 24 August – 11 September 2020 Online Chris Sievers Barrister Lonsdale Chambers, Victorian Bar Presented by: Chris Sievers Lonsdale Chambers, Victorian Bar © Chris Sievers 2020 Disclaimer: The material and opinions in this paper are those of the author and not those of The Tax Institute. The Tax Institute did not review the contents of this paper and does not have any view as to its accuracy. The material and opinions in the paper should not be used or treated as professional advice and readers should rely on their own enquiries in making any decisions concerning their own interests. Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud CONTENTS 1 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 The legislative regime ............................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Missing trader fraud .................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Recent decisions of the Tribunal .............................................................................................. 4 Fraud or tax evasion by another entity in the supply chain ...................................................... 6 2.1 The failure of the supplier to pay GST – general observations ................................................ 6 2.2 “Missing trader” schemes .......................................................................................................... 7 2.2.1 2.3 3 5 The knowledge of the purchaser ............................................................................................ 10 2.3.1 The United Kingdom ........................................................................................................ 10 2.3.2 Australia ........................................................................................................................... 12 The anti-avoidance provisions in Division 165 of the GST Act and “missing trader” fraud 14 3.1 An outline of Division 165 ....................................................................................................... 14 3.2 Division 165 of the GST Act and “missing trader” schemes ................................................... 15 3.3 ACN 154 520 199 Pty Ltd (in liq) and Commissioner of Taxation [2019] AATA 5981 ........... 16 3.3.1 The facts .......................................................................................................................... 17 3.3.2 The alleged scheme ........................................................................................................ 18 3.3.3 GST benefit ...................................................................................................................... 19 3.3.4 Dominant purpose or principal effect of the scheme ....................................................... 20 3.4 4 Gold ................................................................................................................................... 8 Implications of the decision ..................................................................................................... 21 The Commissioner’s administrative approach to “missing trader” fraud ............................. 23 4.1 Cash World Buyers Pty Ltd and Commissioner of Taxation [2020] AATA 1546 .................... 23 4.2 The approach of the Commissioner in the case ..................................................................... 24 4.2.1 The Intermediaries “enterprise” ....................................................................................... 24 4.2.2 Division 142 of the GST Act ............................................................................................ 25 4.2.3 Double recovery ............................................................................................................... 25 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 27 © Chris Sievers 2020 2 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud 1 Introduction 1.1 The legislative regime The GST is a “transaction tax”, with the GST imposed at each stage of a supply chain.1 However, the legislative regime does not intend that the tax is to be an economic burden at each stage throughout a supply chain - resulting in a “cascading” of the tax. The intention is that the economic burden of the tax should only be imposed once, generally upon the ultimate consumer. This legislative aim is achieved by the provision of input tax credits to businesses operating within the supply chain. In HP Mercantile Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2005] FCAFC 126 Hill J (at [13]) described the “genius” of this system in the following terms: The genius of a system of value added taxation, of which the GST is an example, is that while tax is generally payable at each stage of commercial dealings ("supplies") with goods, services or other "things", there is allowed to an entity which acquires those goods, services or other things as a result of a taxable supply made to it, a credit for the tax borne by that entity by reference to the output tax payable as a result of the taxable supply. That credit, known as an input tax credit, will be available, generally speaking, so long as the acquirer and the supply to it (assuming it was a "taxable supply") satisfied certain conditions, the most important of which, for present purposes, is that the acquirer make the acquisition in the course of carrying on an enterprise and thus, not as a consumer. The system of input tax credits thus ensures that while GST is a multi-stage tax, there will ordinarily be no cascading of tax. It ensures also that the tax will be payable, by each supplier in a chain, only upon the value added by that supplier. It is generally expected that throughout the supply chain the prices paid between registered businesses will be “grossed up” on account of GST, on the basis that the supplier will pay GST and the acquirer will receive an input tax credit equal to the GST liability of the supplier. In this respect, the entitlement of the acquiring business to the input tax credit can be said to fund the GST liability of the supplier, or to at least reimburse the purchaser for that funding cost. Where each party complies with their statutory obligations and the GST is paid, the legislative regime works as intended and the transaction is GST neutral for the supplier, the purchaser and the Revenue – with the consumer bearing the economic burden of the GST at the end of the supply chain. 1.2 Missing trader fraud Problems occur when a supplier within a supply chain, upon being funded the GST by the acquirer through an increase in price, fails to pay GST or is engaged in fraud or non-compliance with regards to their statutory obligation to pay GST. This is commonly known as “missing trader fraud”. In these circumstances, the Revenue is left out of pocket where an input tax credit has been paid but the corresponding GST revenue is not received. Whether it is mobile phones, gold, or other activities, the statutory regime can be taken advantage of by parties engaging in missing trader fraud. As an example, in 2002 a UK newspaper reported that 1 In this paper references to the GST Act are to The A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999. © Chris Sievers 2020 3 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud Customs officially estimated the size of fraud through the international trade of mobile phones at 2.6 billion pounds in the 2001 financial year. 2 Australia is not immune. On 31 March 2017, “The Australian” reported that an elaborate GST scam involving gold had so far cost taxpayers more than $700 million in lost tax revenues. 3 1.3 Recent decisions of the Tribunal The issue of missing trader fraud in the gold industry was highlighted by the recent decisions of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal where the Tribunal upheld the Commissioner’s decisions to deny the applicants’ entitlement to input tax credits with respect to the acquisition of gold: ▪ ACN 154 520 199 Pty Ltd (in liq) and Commissioner of Taxation [2019] AATA 59814 ▪ Cash World Gold Buyers Pty Ltd and Commissioner of Taxation [2020] AATA 1546. In the first case the applicant, a gold refiner, satisfied the Tribunal that the gold was acquired in taxable form, but the Tribunal affirmed the decision of the Commissioner to deny the entitlement to input tax credits on the basis that: ▪ The gold was not acquired for a creditable purpose because the gold was not “refined” by the applicant within the meaning of s 38-385 of the GST Act and the sales of gold bullion by the applicant were therefore not GST-free as the first supply of “precious metal” – rather the sales were input taxed under s 40-100 as a supply of “precious metal”. ▪ Alternatively, if the gold was acquired for a creditable purpose, the applicant’s entitlement to input tax credits should be denied pursuant to the operation of the anti-avoidance provisions in Division 165 of the GST Act – on the basis that there was a scheme where the dominant purpose or principal effect of acquiring the gold was to obtain the input tax credits. In the second case, the applicant failed essentially because the Tribunal was not satisfied, on the evidence, that the applicant had acquired the gold as purportedly indicated in the invoices that the gold was “scrap gold” – and therefore taxable – as opposed to gold bullion which was input taxed. However, the decision of the Tribunal highlighted some of the administrative issues facing the Commissioner when trying to address missing trader fraud. The issue of “missing trader fraud” was a common theme. Both decisions: ▪ Disclosed the involvement of “intermediaries” in the supply chain who were able to purchase and sell very large amounts of gold while having limited financial means, and who agreed to sell gold at a price that would mean selling at a loss if the GST was remitted to the Commissioner – making the transactions uncommercial unless the GST was to be retained. ▪ Raised the spectre of gold being “recycled” through the supply chain, with its taxable form being altered at some stage in the supply chain from gold bullion (non-taxable) to “scrap gold” (taxable), and one or more suppliers failing to remit GST. The Guardian Newspaper, “Mobile phone scam costs VAT billions”, 17 August 2002. The Australian Newspaper, “Tax office: $700m GST scam saw gold mules sell in parks”. 4 The taxpayer’s appeal to the Full Federal Court has been heard and we are awaiting judgment. 2 3 © Chris Sievers 2020 4 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud The decisions raise the following issues which are discussed in this paper: ▪ In what circumstances should a purchaser be denied input tax credits where another entity in the supply chain fails to comply with its statutory obligations or is involved in fraud or tax evasion? Are the anti-avoidance provisions in Division 165 effective to achieve this outcome? ▪ How can the Commissioner administratively address missing trader fraud? Where the Commissioner seeks to recover unpaid GST from the missing trader, can the Commissioner also seek to deny a purchaser in the supply chain input tax credits? Can there be a doublerecovery for the Commissioner? © Chris Sievers 2020 5 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud 2 Fraud or tax evasion by another entity in the supply chain Under the GST regime, if a registered entity makes a “creditable acquisition” within the meaning of s 11-5, that entity is entitled to an input tax credit that equals the GST payable by the supplier: s 11-25. The credit can generally only be claimed where the entity has received a tax invoice from the supplier. The tax invoice informs the entity of a number of matters, including the supplier’s ABN, the nature of the supply, the amount of the GST payable and the price. The tax invoice is intended to be a statement by the supplier that can be relied on by the acquirer to confirm that it is acquiring a taxable supply from the supplier and that the supplier is liable to pay GST of a particular amount to the Commissioner. As noted in GSTR 2013/1 ‘GST: tax invoices’ at paragraph 5: The requirement to issue a tax invoice is a key component of the integrity of the GST system. It forms an essential part of the audit trail and is an important indicator that a taxable supply has been made. Another important indicator that a taxable supply has been made is that the supplier is registered for GST and has an ABN. In addition to the inclusion of the supplier’s ABN on the tax invoice, an acquiring entity is able to conduct an independent verification of that ABN and GST registration by conducting a search on the “ABN Lookup” website. Other than ensuring receipt of a valid tax invoice, and potentially verifying the information by carrying out a search of the supplier’s ABN, an entity is not required to do anything else in order to claim an input tax credit. Its statutory entitlement to the credit operates pursuant to the operation of the GST Act. But what if the supplier fails to pay the GST? 2.1 The failure of the supplier to pay GST – general observations Under the basic rules in Chapter 2 of the GST Act, the failure of the supplier to pay its GST liability has no impact on the entitlement of the acquiring entity to claim an input tax credit. The amount of the input tax credit equals the GST “payable” by the supplier - whether or not the GST is actually paid is irrelevant. It is also irrelevant whether the purchaser knew, or should have known, that the supplier has not paid, or was not intending to pay the GST. An acquiring entity is under no obligation to enquire as to whether the supplier has paid, or will pay, the GST. This is an intended outcome of the legislative regime, as the statutory rights and obligations of the supplier and the acquirer under the GST Act operate independently of each other. The respective BASs lodged by the supplier and the acquirer are deemed to be an assessment of that entity’s net amount. They are separate and independent assessments. If the supplier fails to report its GST liabilities to the Commissioner or fails to pay the net amount reported in its BAS, that is a matter between the Commissioner and the supplier. Any unpaid amounts will be a debt due by the supplier to the Commissioner. An example of an arrangement where a supplier fails to comply with its GST obligations is the practice of “phoenixing” by property developers. Under this practice, a registered entity undertakes a © Chris Sievers 2020 6 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud property development and recovers input tax credits with respect to the development costs. During the construction phase, no taxable supplies are made and for each BAS the developer is entitled to a cash refund of the input tax credits. Once the development is completed, the developer makes taxable supplies of the developed lots and receives the GST component of the price from purchasers. However, the developer dissolves its business before lodging its BAS to avoid remitting the GST. The developer thereby pockets the cash refunds from the input tax credits plus the unpaid GST. In February 2018, legislation was introduced to address this practice by requiring purchasers of new residential premises to withhold the GST and to pay the GST directly to the Commissioner at or before settlement.5 The Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill stated that phoenixing to avoid paying GST had grown significantly over the last decade and as of November 2017 the ATO had identified 3,731 individuals that had actively engaged in that activity over the last 5 years. These individuals controlled over 1,200 insolvent entities responsible for $1.8 billion in debt that had been written off and had claimed $1.2 billion in input tax credits. Where the supplier is involved in “phoenix” activity, or the supplier simply fails to pay its GST liabilities, the purchaser will usually be an innocent participant in the transaction. In such circumstances, the purchaser should not be denied its right to claim input tax credits or a refund (if available under the Act). But what if the purchaser has actual knowledge, or should have known, that its supplier was not going to pay the GST – or that its acquisition was part of a broader supply chain when where one of the participants was engaged in fraud or tax evasion? Should the purchaser’s entitlement to input tax credits be questioned in those circumstances? The issue is illustrated by a consideration of “missing trader” schemes which are common in VAT regimes around the world. 2.2 “Missing trader” schemes A “missing trader” scheme is where one of the parties to a supply chain engages in fraud or tax evasion, fails to pay its GST liabilities and goes into liquidation or disappears. That party will effectively “pocket” the GST component of the price paid to it by a purchasing entity. If the purchasing entity claims an input tax credit and the Commissioner is ultimately unable to recover the GST from the supplier entity, there will be a loss to the revenue. The Commissioner will have paid the input tax credit to the acquirer but cannot recover the GST liability from the supplier. In POWA (Jersey) Ltd v HMRC [2012] UKUT 50 Roth J described the concept (referred to as “MTIC fraud”) in the following terms: 5…goods (almost always small but valuable items such as mobile phones and computer chips) are acquired by a registered trader in the United Kingdom from a trader in another member State, and sold to a second UKregistered trader. The goods then usually change hands several times within the UK before they are sold to an overseas trader which, if it is located in a member State of the European Union, is registered for VAT in that member State. Commonly the transactions all occur within a few days of the entry of the goods into the UK, 5 Treasury Laws Amendment (2018 Measures No.1) Act 2018, Schedule 5 introducing Subdivision 14E into Schedule 1 of the Taxation Administration Act 1953. © Chris Sievers 2020 7 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud sometimes even on the same day, so that goods enter the UK in the morning, pass through the hands of several UK traders during the day, and are exported again in the afternoon. 6. The first UK vendor, the acquirer from overseas, charges VAT on the consideration paid by his purchaser, but fails to account to the respondent Commissioners for that tax, and disappears. Such documentation as he may have had - if any - relating to his acquisition is never produced to the Commissioners. For the scheme to work he must be a VAT-registered trader who provides the purchaser with a genuine VAT invoice, on the strength of which the purchaser claims an input tax credit. The purchaser’s own sale, and those of the other UK traders save the last in the sequence, usually generate a small profit and, consequently, a small net VAT liability, for which the traders account. The last trader, selling overseas, claims credit for the input tax he has incurred, but has no output tax liability since the sale is zero-rated. Usually this trader makes a significant profit, though that is not invariably the case: occasionally one of the antecedent traders can be shown to have made the greatest profit of all those in the chain. All of these sales and purchases, including the sale to the overseas buyer, are almost always properly documented. One can readily see how a similar scheme could operate with respect to GST in Australia. For example, a registered entity sells goods to another registered entity for a “grossed up” price that includes GST, fails to account to the Commissioner for the GST and disappears. The purchasing entity then sells the goods to one or more entities as taxable supplies until the final entity exports the goods as a GST-free supply. The final entity has no GST liability because the supply is GST-free but is entitled to an input tax credit and will therefore be in a refund position. The Revenue is out of pocket because it has paid an input tax credit but has not received the GST. 2.2.1 Gold “Missing trader” schemes can also be implemented where a particular good can have different tax treatments. A ready example is precious metal, such as gold, the supply of which can be taxable, GST-free or input taxed, depending upon the form of the gold and the nature of the transaction. In each of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United Kingdom, the treatment of gold can be as follows: ▪ Input taxed if the gold is of a fineness of at least 99.5% and, other than New Zealand, if the gold is also in a tradeable form (such as a bullion bar with a hallmark) - here referred to as “precious metal”. ▪ GST-free if it is the first supply of “precious metal” after its refining. ▪ Taxable if it is not “precious metal”. In the course of the IGOT investigation into GST refunds,6 the ATO provided the following illustration of a hypothetical “missing trader” arrangement involving gold. 6 Inspector General of Taxation, ‘GST Refunds’, March 2018. © Chris Sievers 2020 8 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud Figure 8: Hypothetical ‘missing trader’ illustration The ATO described the stages of the arrangement as follows: ▪ Stage 1 - the Missing Trader purchases gold bullion from a Bullion Dealer for $1,030. It is treated as an input taxed supply of precious metal or is GST-free if it is the first supply following its refinement. ▪ Stage 2 - the Missing Trader melts, scratches or cuts the bullion to make it taxable as scrap gold and sells it to a Gold Seller for $1,078. GST attached to the transaction is $98. The mischief arises where the Missing Trader does not lodge its BAS or remit the GST and, therefore, makes a profit of $48. If the Missing Trader had lodged its BAS and remitted the GST, they would have made a loss of $50. ▪ Stage 3 - the Gold Seller sells the scrap gold to a Gold Refiner for $1,100. The sale has $100 GST attached to it which the Gold Seller remits. The Gold seller is also entitled to a credit of $98 (for the GST paid in Stage 2) and remits a net amount of $2, making a profit of $20. ▪ Stage 4 - the Gold Refiner refines the scrap gold and sells it as bullion for $1,020 to the Bullion Dealer. This transaction is treated as the first supply of bullion after refinement which is GST-free. The Gold Refiner is not required to remit any GST but is entitled to claim an input tax credit of $100 (for the GST paid in Stage 3). The credit offsets the loss of $80 that would otherwise have been made and the Gold Refiner makes a profit of $20. ▪ The cycle commences again with the Bullion Dealer and Missing Trader transactions at Stage 1. The total loss of GST revenue from each set of the above hypothetical transactions was $98. The ATO characterised the loss as representing the $100 refund received by the Gold Refiner (stage 4) © Chris Sievers 2020 9 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud and the net GST of $2 remitted by the Gold Seller (stage 3). However, the loss could equally be characterised as simply the failure of the Missing Trader to pay GST (stage 2). To address the operation of these schemes, in 2017 the GST Act was amended to introduce a reverse charge on the taxable supply of precious metals.7 The effect of the amendment is to impose the GST liability on the recipient of a taxable supply of precious metals. The Explanatory Memorandum explained the rationale for the amendment as follows: 1.1 This Bill introduces a mandatory reverse charge for taxable supplies between suppliers and purchasers of gold, silver and platinum. This removes the opportunity for fraudulent input tax credit claims by the purchaser and for the supplier to avoid paying goods and services tax (GST) to the Commissioner by liquidating… 1.5 The objective of the announced changes is to combat ‘missing trader’ schemes in the gold industry, which if left unaddressed would continue to present an integrity risk to the GST system… 1.6 The schemes identified have involved entities altering gold such that it no longer meets the definition of a ‘precious metal’ under the GST Act… 1.8 The ‘form’ of gold and other metals can be readily changed without any sophisticated process. This may include defacing, scratching off hallmarks, melting, granulating, cutting or chopping the metal, such that it is no longer in ‘investment form’. 1.9 A supply of the altered metal would be treated as a taxable supply under the GST Act, whereas supplies of precious metals are input taxed under section 40-100 or GST-free under section 38-385 and are therefore not taxable supplies (refer section 9-5) Missing trader schemes 1.10 Generally, when a taxable supply of goods is made, the purchaser (i.e. recipient of the goods) pays GST to the supplier of the goods and then later claims an input tax credit when lodging their business activity statement (BAS) with the Commissioner. The supplier typically receives the GST component as part of the sale price at the time of sale and is required to remit GST to the Commissioner later, when they lodge their BAS. 1.11 The missing trader schemes identified have involved taxable supplies of altered metal, where the supplier liquidates or otherwise goes missing without remitting the GST to the Commissioner. The purchaser of the altered metal then claims an input tax credit on the supply. The amendments apply from 1 April 2017, which was the date of the announcement of the amendments. 2.3 The knowledge of the purchaser 2.3.1 The United Kingdom In the United Kingdom, the Courts developed an approach whereby the entitlement of an acquiring entity in a supply to claim a credit (referred to as a deduction) with respect to the VAT paid to a supplier will be lost where it is established that the entity “knew or should have known” that, by their purchase, they were taking part in a transaction connected with the fraudulent evasion of VAT. Under this approach, the entitlement to a credit may be denied even if the claimant did not profit from the transaction. 7 Section 86-5 of the GST Act which was introduced by the Treasury Laws Amendment (GST Integrity) Act 2017. © Chris Sievers 2020 10 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud The legal basis for the approach was established in Kittel v Belgium, Belgium Recolta Recycling [2006] ECR 1-6161. The Court observed as follows: 55. Where the tax authorities find that the right to deduct has been exercised fraudulently, they are permitted to claim repayment of the deducted sums retroactively…It is a matter for the national court to refuse to allow the right to deduct where it is established, on the basis of objective evidence, that the right is being relied on for fraudulent ends… 56. In the same way, a taxable person who knew or should have known that, by his purchase, he was taking part in a transaction connected with fraudulent evasion of VAT must, for the purposes of the Sixth Directive, be regarded as a participant in that fraud, irrespective of whether or not he profited by the resale of the goods. 57. That is because in such a situation the taxable person aids the perpetrators of the fraud and becomes their accomplice. 58. In addition, such an interpretation, by making it more difficult to carry out fraudulent transactions, is apt to prevent them… 61….where it is ascertained, having regard to objective factors, that the supply is to a taxable person who knew or should have known that, by his purchase, he was participating in a transaction connected with fraudulent evasion of VAT, it is for the national court to refuse that taxable person entitlement to the right to deduct. The test was further clarified by Moses LJ in Mobilx Ltd v Revenue and Customs [2010] EWCA Civ 157. His Lordship observed (at [24]) that the scope of VAT, the transactions to which it applies, and the persons liable to the tax are defined according to objective criteria of uniform application and that: …the objective of the common system of VAT of ensuring legal certainty and facilitating the measures necessary for the application of VAT by having regard, save in exceptional circumstances, to the objective character of the transactions concerned. His Lordship then observed (at [30]): …the Court made it clear that the reason why fraud vitiates a transaction is not because it makes the transaction unlawful but rather because where a person commits fraud he will not be able to establish that the objective criteria which determine the scope of VAT and the right to deduct have been met. On the question of knowledge, his Lordship provided the following guidance: 52. If a taxpayer has the means at his disposal of knowing that by his purchase he is participating in a transaction connected with fraudulent evasion of VAT he loses his right to deduct, not as a penalty for negligence, but because the objective criteria for the scope of that right are not met. It profits nothing to contend that, in domestic law, complicity in fraud denotes a more culpable state of mind than carelessness, in the light of the principle in Kittel. A trader who fails to deploy means of knowledge available to him does not satisfy the objective criteria which must be met before his right to deduct arises. The approach in the UK operates as an exception to the basic VAT rules and it gives the Revenue an effective tool with which to combat VAT and fraud and “missing trader” schemes. The approach also imposes an obligation on entities involved in supply chains to undertake a level of due diligence and risk assessment. The Revenue’s view on the scope of this obligation is outlined in its internal manual on “VAT Fraud”.8 The manual includes the following matters: ▪ Taxable persons should not undertake due diligence and risk assessments just to satisfy the Revenue but to help ensure that the business is managed effectively and to ensure the integrity of their supply chains. HMRC internal manual “VAT Fraud: Due Diligence and risk assessment: Why a taxable person should undertake due diligence and risk assessment”. Published 10 April 2016, last updated 13 January 2020. 8 © Chris Sievers 2020 11 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud ▪ The due diligence and risk assessments should be reasonable and proportionate and demonstrate that the taxable person is managing any risks to his business. ▪ Before entering into a transaction or a particular market, a taxable person should consider the risks associated with that transaction and/or market. This can mean anything from undertaking research on the product/market, researching the supplier(s) and customer(s), entering into written contracts etc. The taxable person also needs to take into consideration the way in which the transaction has occurred or is about to occur. ▪ The mere failure of a taxable person to carry out due diligence/risk assessment will not by itself be sufficient to establish that a taxable person “should have known” it was involved in VAT fraud. However: ▪ Where the Revenue can establish that checks on the taxable person’s suppliers, customers, freight forwarders etc, would have given cause for concern, this will be highly relevant in deciding whether the taxable person “should have known”. ▪ If other indicators suggest that the transactions were contrived, deficiencies in the due diligence/risk assessment may help support a case where the Revenue allege that the taxable person knew that it was involved in VAT fraud or that its transactions were connected with fraudulent evasion of VAT, since it may be inferred that the taxable person failed to carry out meaningful due diligence/risk assessment because it knew it was unnecessary, since the transaction(s) had been pre-arranged. 2.3.2 Australia To date, the United Kingdom approach has not been considered in Australia. My research has not identified any decision of a Tribunal or a Court where the decisions in Kittel or Mobilx have been considered. If such an approach was adopted, it would likely operate as an exception to s 11-5 of the GST Act, with the effect that an entity would not have made a creditable acquisition (and would thereby not be entitled to input tax credits) if the entity knew, or should have known, that, by their purchase, they were taking part in a transaction connected with the fraudulent evasion of GST. The first real opportunity for a Court or Tribunal in Australia to consider the issue of GST fraud and “missing trader” schemes was the recent Tribunal decision in ACN 154 520 199 Pty Ltd (in liq) and Commissioner of Taxation [2019] AATA 5981. The Tribunal affirmed the decision of the Commissioner to deny the applicant’s entitlement to input tax credits with respect to the acquisition of scrap gold where other entities in the supply chain had fraudulently failed to pay GST. The Tribunal concluded that (at [271]) the applicant was “on notice (and in some cases had actual knowledge) of the fraudulent activities of the [missing traders]” and (at [279]) that the applicant was “at best, wilfully blind to the creation of a contrived market in gold transactions which entitled it to claim input tax credits upon its acquisitions of scrap gold from [the missing traders]”. While these factual findings would likely satisfy the requirements for the UK approach, the Tribunal did not consider whether it was appropriate to introduce a similar approach in Australia and the Commissioner did not appear to make any submission to this effect. Instead, the Tribunal agreed with the Commissioner that the applicant’s entitlement to input tax credits should be denied by reason of the application of the anti-avoidance provisions in Division 165 of the GST Act. This was on the basis that: there was a “scheme”; the applicant’s entitlement to input tax credits was a “GST benefit” that the applicant got © Chris Sievers 2020 12 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud from the scheme; and that the sole or dominant purpose of the applicant (and other participants in the scheme) in entering into or carrying out the scheme was to create the applicant’s entitlement to input tax credits. The decision of the Tribunal establishes Division 165 as a path whereby the Commissioner may look to address the impact of “missing trader” GST schemes and the loss of revenue that follows. The effect of the Tribunal decision is that where an entity in a supply chain makes a creditable acquisition in circumstances where that price is “grossed up” for GST and the entity claims an input tax credit to recover the cost of funding that GST, the entity may be exposed to the operation of Division 165 if another entity within the supply chain fails to pay its GST liability to the Commissioner. Noting that the Full Federal Court has reserved its decision in the appeal brought by the taxpayer, this paper will undertake a detailed review of this important decision. © Chris Sievers 2020 13 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud 3 The anti-avoidance provisions in Division 165 of the GST Act and “missing trader” fraud 3.1 An outline of Division 165 In Commissioner of Taxation v Unit Trend Services Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 16; 250 CLR 523 the High Court observed that Division 165 contains anti-avoidance provisions that operate to nullify schemes which have the purpose or effect of reducing GST, increasing refunds, or altering the timing of payment of GST or refunds – with such effects being described as “GST benefits”.9 The Court observed that, in broad summary, Division 165 applies where: ▪ There is a scheme, from which an entity gets a GST benefit; ▪ The entity or some other entity entered into or carried out the scheme for the sole or dominant purpose of getting the GST benefit; ▪ Alternatively, the principal effect of the scheme was that the entity or some other entity gets the GST benefit; and ▪ The GST benefit is not attributable to the making by the entity of a choice expressly provided for by the Act. Where those requirements are satisfied, the Commissioner is empowered to make a declaration negating the GST benefit. “Scheme” is defined broadly to mean:10 (a) any arrangement, agreement, understanding, promise or undertaking; (i) whether it is express or implied; and (ii) whether or not it is, or is intended to be, enforceable by legal proceedings; or (b) any scheme, plan, proposal, action, course of action or course of conduct, whether unilateral or otherwise. An entity will get a “GST benefit” from a scheme if, inter alia:11 (a) an amount that is payable by the entity under this Act, apart from this Division is, or could reasonably be expected to be, smaller than it would be apart from the scheme or a part of the scheme; or (b) an amount that is payable to the entity under this Act, apart from this Division is, or could reasonably be expected to be, larger than it would be apart from the scheme or a part of the scheme… In Unit Trend, the High Court (at [59]) observed that in the context of a liability to pay GST the GST benefit the entity gets from a scheme is the difference, as to quantification, between: (a) an amount 9 At [4] referring to s 165-1. Section 165-10(2). 11 Section 165-10(1). 10 © Chris Sievers 2020 14 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud that would be payable by the entity under the GST Act absent Division 165 with the scheme in existence; and (b) such amount as would have been payable by the entity under the GST Act without the scheme in existence. Applying this reasoning to the receipt of an input tax credit, the GST benefit is the difference, as to quantification between: (a) an amount that would be payable to the entity under the GST Act absent Division 165 with the scheme in existence; and (b) such amount as would have been payable to the entity under the GST Act without the scheme in existence. In determining whether an entity (whether alone or with others) entered into or carried out the scheme with the sole or dominant purpose of that entity or another entity getting a GST benefit from the scheme, or the principal effect of the scheme was that the avoider gets the GST benefit from the scheme, the matters set out in s 165-15(1) must be taken into account. These matters include: ▪ the manner in which the scheme was entered into or carried out; ▪ the form and substance of the scheme; ▪ the timing of the scheme; ▪ any change in the avoider’s financial position that has resulted, or may reasonably be expected to result, from the scheme; and ▪ the circumstances surrounding the scheme. 3.2 Division 165 of the GST Act and “missing trader” schemes The result of “missing trader” schemes is that the Commonwealth is out of pocket to the extent that it has not received any GST from the missing trader but has paid out input tax credits to another entity in the supply chain that made a creditable acquisition (the “claimant”). This creditable acquisition may or may not have been made directly from the missing trader as there may have been one or more intermediate taxable supplies. If it is accepted that the arrangement is a “scheme” for the purposes of Division 165, and the relevant scheme includes the taxable supply by the missing trader and the creditable acquisition by the claimant, the GST benefit to the claimant could be said to be the difference between: (a) the input tax credits payable with respect to the creditable acquisition absent Division 165 with the scheme in existence; and (b) such amount as would have been payable to the entity under the GST Act without the scheme in existence. Without the scheme, there would be no taxable supply by the missing trader and no creditable acquisition by the claimant and no input tax credit entitlement. The same result could be said to occur for any creditable acquisition made by an entity, whether as part of a supply chain or as a single transaction. Any transaction where an entity makes a creditable acquisition could be regarded as a “scheme” and the acquirer’s entitlement to an input tax credit could be said to be a “GST benefit” within the literal meaning in s 165-10(1)(b). It appears therefore that the critical question to be answered in each case is whether the acquirer (whether alone or with others) entered into or carried out the relevant “scheme” with the sole or dominant purpose of getting the GST benefit or that was its principal effect. Where, as will usually be the case, the price paid for the creditable acquisition has been grossed up for GST, the entitlement to input tax credits does not give the acquirer any net financial benefit – rather it simply reimburses the acquirer for the cost of paying the GST component to the supplier. In this regard, where an isolated transaction is involved, it is difficult to see how the receipt of that input tax credit can be regarded as © Chris Sievers 2020 15 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud the sole or dominant purpose or the principal effect of that transaction. The dominant purpose and principal effect would appear to be the acquisition of the goods or service in question, with the GST an incidental or secondary matter. The question is whether a different result may flow where the transaction is part of a broader supply chain and an entity in that supply chain fails to discharge its GST liabilities – such as a “missing trader” schemes. In ACN 154 520 199 Pty Ltd (in liq) and Commissioner of Taxation [2019] AATA 5981 the Tribunal agreed with the Commissioner that it could. 3.3 ACN 154 520 199 Pty Ltd (in liq) and Commissioner of Taxation [2019] AATA 5981 The Tribunal (at [1]) observed that the case arose “out of an arrangement, in which the applicant played an integral role, that exploits features of the [GST Act] to conjure input tax credits out of dealings in gold”. This was a very substantial matter, being heard over 13 days and involving more than 60,000 “T documents” being filed with the Tribunal and a hearing book consisting of 13 folders. The applicant, a refiner of precious metal, claimed it was entitled to input tax credits because: it paid a GST-inclusive price when it acquired scrap gold for refining from third-party suppliers; processed the scrap gold into investment-grade bullion with a metallic fineness of at least 99.5% (being “precious metal” as defined in the GST Act); and made GST-free supplies of that bullion dealers pursuant to s 38-385 – being the first supply of that precious metal after its refining. The Commissioner’s primary argument was that the applicant did not make creditable acquisitions because the supplies of bullion were not GST-free pursuant to s 38-385 – rather, they were input taxed supplies of precious metal pursuant to s 40-100. This was because the gold acquired was already at 99.99% fineness and the process applied by the applicant to put the gold into bullion form12 was not “refining” for the purposes of s 38-385 - the gold had already been refined to the requisite standard before it was acquired by the applicant. The Tribunal agreed with the Commissioner’s argument. In the alternative, the Commissioner relied on declarations made under Division 165 disallowing the input tax credits for a sub-set of the acquisitions. The issue was summarised by the Tribunal as follows: 6. Broadly, it transpired that a number of the third-party suppliers were pocketing the GST they should have remitted to the Commissioner after making taxable supplies of scrap gold to the applicant. The applicant shrugs at this, saying any loss to the revenue is a matter between the Commissioner and the rogue suppliers who have failed to comply with their GST obligations. The applicant says it claimed its input tax credits in the usual way, and that it paid GST to the rogue suppliers in the GST-inclusive prices for the scrap gold. The Commissioner does not allege the applicant was a party to any fraud by third-parties, but he says Div 165 was applicable because: At [82]: The evidence of the applicant’s director was that every piece of scrap gold received was melted down and subjected to a smelting and fluxing process. This was said to be the invariable practice, even where the scrap in question was defaced or damaged precious metal bars that bore a recognised hallmark confirming the bar was of 99.99% fineness. The Tribunal found that the motivation for the practice was clear from the evidence. No refinery, and certainly not the applicant, was prepared to accept anybody else’s word for the purity of the product it acquired. The Tribunal observed that the director insisted that nothing could be accepted at face value and the material always had to be melted and analysed for quality control purposes. 12 © Chris Sievers 2020 16 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud (a) the applicant had obtained a GST benefit in the form of the input tax credits from a scheme; and (b) one or more entities (including the third-party suppliers) entered into or carried out the scheme for the dominant purpose of giving the applicant the GST benefit, or the principal effect of the scheme was that the applicant got the GST benefit. The Tribunal observed (at [225]) that the Commissioner made clear that he was not alleging the applicant was a party to the fraud being perpetrated by the missing traders, but he contended that the applicant was a willing and informed beneficiary of the scheme because it received the benefit of input tax credits in connection with its acquisition of this suspiciously rich and surging taxable supply of gold. The Tribunal agreed with the Commissioner’s argument and, while it was strictly unnecessary to do so given the finding on the “refining” issue, the Tribunal provided detailed reasons for its decision. In taking this course, the Tribunal observed (at [132]) that there was limited guidance from the courts and the Tribunal as to the operation of Division 165 and, specifically, none that address “missing trader” or “carousel fraud” arrangements of which the present arrangement was an example. This paper will focus on this aspect of the decision. 3.3.1 The facts The Tribunal’s conclusion in the application of Division 165 appears to be heavily reliant upon its evidentiary findings, which included the following: ▪ The applicant was a refiner of precious metals and it acquired a large volume of scrap gold from a relatively small pool of suppliers as part of a business strategy which targeted suppliers of secondary material. ▪ The applicant did not always know where the suppliers sourced their material because suppliers tended to be secretive for reasons of their own. But the applicant did know: ▪ that a few of its main suppliers were sourcing material from an associated company (a dealer in precious metal) to whom, with and to another company, the applicant sold most of its precious metal; and ▪ ▪ that a proportion of the material delivered to the applicant was in the form of damaged bars or in other forms which were likely to have been comprised of gold that had been in investment form but which had been melted to disguise its provenance. The suppliers of scrap gold to the applicant were engaged in tax evasion through the nonremittance by the suppliers of the GST on its taxable supplies of scrap gold - the suppliers were in that sense the ‘missing traders’ in the supply chain. ▪ There was a circular flow of gold between the dealer associated with the applicant, the ▪ missing trader and the applicant. It was to be inferred that the same gold (or at least some of it) was being recycled in these ▪ supply chains. With regards to the knowledge of the applicant as to the activities of the missing traders, the Tribunal made the following findings: ▪ The applicant was aware that the missing traders were acquiring investment-grade bullion from dealers. ▪ © Chris Sievers 2020 The applicant more than likely knew that the missing traders were altering the bullion so it was no longer in investment form to make taxable supplies to the applicant. 17 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud ▪ The applicant was on notice that the missing traders were not remitting the GST because it would have been uneconomic for them to do so. In making this finding, the Tribunal observed as follows: 224…We reach that conclusion, in particular, based on the prices at which they bought the precious metal from the Dealers or other intermediaries, namely, ‘spot price plus a premium’, and the prices at which the [missing traders] later sold the scrap gold (whether or not it was the same gold) to the applicant for refining. The price paid by the applicant was a GSTinclusive price, namely, ‘spot price less a discount plus GST’ with the GST liability owed to the Commissioner. However, it was only economically feasible for the suppliers to undertake the transactions if they recovered the GST in the price of the scrap gold from the applicant but did not remit the GST to the Commissioner. 3.3.2 The alleged scheme The Commissioner alleged that there was a wider and a narrower scheme. The wider scheme broadly comprised the following elements: ▪ the supply by the applicant to dealers of gold of 99.99% in investment form for an amount roughly equivalent to the prevailing spot price for gold; ▪ ▪ the purchase by the missing traders of gold of 99.99% in investment form; the scratching, melting or altering of the gold such that, while still of 99.99% fineness, the gold ▪ was no longer in investment form for the purposes of the definition of “precious metal”; the supply of the gold by the missing traders to the applicant for an amount that was less than the prevailing spot price for gold, before the addition of GST; and ▪ the refining by the applicant of the gold to produce “precious metal”. The narrower scheme did not include the first and last of the above elements. The Tribunal (at [239]) gave the following description of the Commissioner’s explanation as to the scheme: 239. Broadly, the Commissioner explained that the scheme required the participation of a refiner, here the applicant, that would acquire the scrap gold to make supplies of precious metals…The Commissioner further submitted that the purpose of defacing the precious metal that was acquired from the Dealers into non-investment form precious metal, which was an integral step in both the wider and narrower schemes, was fundamental to the scheme as it enabled the [missing traders] to make taxable supplies to the applicant such that it would pay the higher GST-inclusive prices to the [missing traders]. In this way, the making of taxable supplies to the applicant enlivened the entitlement to claim input tax credits. The Commissioner says it was the GST net amounts paid by the Commonwealth to the applicant that funded the arrangement and that made it attractive to the [missing traders]. With respect to the schemes posited by the Commissioner, the applicant contended that it did precisely the things it did in its day-to-day operations - its relevant involvement in the scheme was buying scrap gold, refining it and selling it as precious metal. Further, there was no agreement, arrangement or understanding between the other persons involved in the scheme and the applicant the alleged schemes were merely a temporal sequence of independent, unplanned and uncoordinated sequence of events. The Tribunal (at [244]) concluded that there was a scheme, being comprised of the steps in the wider scheme referred to by the Commissioner. In coming to this conclusion, at [245]-[252] the Tribunal made the following observations: © Chris Sievers 2020 18 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud ▪ The missing traders did not have access to legitimate scrap metal or the ability to fund transactions of that value on a repetitive basis. ▪ The Tribunal was satisfied that the missing traders mostly acquired investment-grade bullion from the dealers and then altered the bullion into scrap gold to make taxable supplies to the applicant. ▪ ▪ The Tribunal agreed with the Commissioner that the scheme only works to the extent that there is a refiner, here the applicant, that acquires and sells metal on its own account and produces “precious metal”. The evidence supports a finding that there was a level of sophisticated planning and interaction between the parties that were involved in each of the supply chains. ▪ The “scheme” involved a carousel type arrangement based on supplying gold for refining after deliberately altering its form. This was not plain carousel fraud involving transactions with the missing traders not remitting GST on their taxable supplies to the Commissioner. There was an additional feature that was key to the arrangement, being the contrived and artificial defacing of the precious metal to take advantage of the different treatments of metal under the GST Act - that was an integral step in both the wider and narrower schemes. ▪ The applicant acquired the scrap gold from the missing traders at a GST-inclusive price that always exceeded the spot price. No refiner would pay those prices unless they were entitled to claim the input tax credits. ▪ ▪ The applicant made a profit because of the input tax credits. Without the input tax credits, the transactions with the missing traders at just below the spot price plus GST would not have been economically feasible for the applicant. The reality is that the GST was never factored into the prices charged by the missing traders to the applicant because they never intended to pay the GST to the Commissioner, and never did pay it. The applicant made its profit from the input tax credits it claimed in relation to the pricing of scrap gold in an artificial market sustained by the missing traders who never ▪ paid their GST liability. The Tribunal concluded that the applicant was not an innocent party in the wider or narrower scheme. Further: ▪ The applicant knew that it was uneconomic for the missing traders to sell scrap gold to it at a price that was effectively less (on a GST-exclusive basis) than that for which the missing traders were buying essentially the same gold, in the form of precious metal from the dealers, unless they were not remitting the GST on those taxable ▪ supplies. The scheme was perpetuated by the applicant due to the input tax credits it received from the Commissioner. That was the economic benefit being shared amongst the ▪ participants to the scheme. It was unnecessary to find whether the applicant had a role in orchestrating the scheme and in procuring the missing traders to carry out their part, including the defacing of the precious metal before presenting it for refining to the applicant. 3.3.3 GST benefit In the absence of evidence from the applicant to suggest what it would have done apart from the scheme, the Tribunal inferred (at [258]) that it was unlikely that the applicant would have made the same number of acquisitions of scrap gold, or at all. The Tribunal considered that this seemed to be © Chris Sievers 2020 19 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud the obvious and inevitable outcome. In the absence of the scheme, the arrangement would not have been economically feasible and the applicant would not have acquired scrap gold in that volume and of that quality at those prices. 3.3.4 Dominant purpose or principal effect of the scheme The Tribunal (at [260]) observed that the heart of the application of Division 165 in a case like this was whether the scheme, or a part of the scheme, was entered into or carried out by any of the participants for the sole or dominant purpose of enabling the applicant to get a GST benefit from the scheme. The Tribunal also observed that the relevant purpose need not be attributed to the taxpayer, it was sufficient that the purpose can be attributed to any one participant in the scheme. 13 The Commissioner contended that the applicant and the missing traders entered into or carried out the scheme with the sole or dominant purpose of the applicant getting a GST benefit which was the input tax credits for its acquisitions and for which the applicant paid GST-inclusive prices to the missing traders. The applicant’s contentions were as follows: ▪ It was not reasonable to conclude any participant in the scheme (in either formulation) entered into or carried out the scheme, or a part of the scheme, for the dominant purpose of the applicant getting a GST benefit. ▪ ▪ The applicant accepted (based on the evidence produced), that certain rogue suppliers altered the gold to make taxable supplies to the applicant, collected GSTinclusive prices from the applicant and then fraudulently retained that GST. However, the applicant distanced itself from that fraudulent conduct and argued its dominant purpose was not to secure input tax credits but to acquire scrap gold it needed to produce precious metal. ▪ It was irrational to suggest the dominant purpose of a taxpayer acquiring goods that are critical to its business is not to obtain the goods themselves but to simply obtain the input tax credits. ▪ ▪ In any event, the availability of input tax credits to the applicant was an expected and natural incident of the payment of GST-inclusive prices. It was not the principal effect of the scheme that the applicant received the GST benefit. The principal effect was to enable the rogue suppliers to sell scrap gold to third party purchasers including the applicant as a taxable supply, thereby enabling those suppliers to recover GSTinclusive prices and fail to remit the GST to the Commissioner. ▪ This was a step that could not be explained other than by reference to tax evasion on ▪ the part of the missing traders. The availability of input tax credits to the applicant was irrelevant to the purpose and effect of any scheme participant. The Tribunal (at [268]) considered that the applicant’s arguments had a superficial appeal. However, the reality was that the applicant’s entitlement to the input tax credits were more important to the 13 Referring to Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Macquarie Bank Ltd (2013) 210 FCR 164 at [289]-[290]; Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Ludekens (2013) 214 FCR 149 at [243]-[246]. © Chris Sievers 2020 20 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud operation of the scheme than the GST liabilities evaded by the missing traders. The Tribunal observed as follows: The input tax credits paid by the Commonwealth to the applicant funded the round-robin arrangements because, in simple terms, it was only economically feasible for the applicant to pay those GST-inclusive prices to the [missing traders] in the knowledge that the applicant would receive the input tax credits. Without the entitlement to the input tax credits, the applicant would not have paid those prices to the [missing traders] and, consequently, there would have been no acquisition of precious metal by the third party suppliers (including the [missing traders]) from the Dealers. There would have been no defacing of that precious metal, no taxable supplies in altered form to the applicant, no processing of the metal by the applicant, and no sale of an equivalent amount of precious metal back into the market by the applicant to the Dealers, and so on. In other words, the round robin arrangements would have fallen over if the applicant had not been able to claim the input tax credits. It was the GST benefit in the form of the larger input tax credits payable by the Commonwealth to the applicant, because of the [missing traders] making taxable supplies to the applicant, that underpinned the scheme. In coming to this conclusion, the Tribunal appears to have accepted that the entitlement of the applicant to input tax credits and the evasion of tax by the avoiders were both relevant to the operation of the scheme - however, it concluded that the entitlement to input tax credits was the more important. In doing so, the Tribunal appears to have applied a “but for” test. But for the entitlement of the applicant to input tax credits - nothing else would have happened. 3.4 Implications of the decision The Tribunal conducted a detailed review of the evidence. A matter of clear concern to the Tribunal was the significant quantity of gold purchased from entities with limited trading histories and limited financial capacity, and the apparent lack of any real due diligence by the applicant. At [184] the Tribunal stated as follows: As the Commissioner pointed out, this is not what one would expect from businesses trading in the volumes of gold the applicant was acquiring from them. Ordinarily, one would expect the applicant to pause before dealing with newly established companies claiming to have the financial means to engage almost immediately in gold dealings of such large volumes and values, but it appears the applicant was not at all concerned. Further, while the Commissioner did not contend that the applicant was a party to the fraud, the Tribunal concluded (at [279]) that the applicant was, “at best, wilfully blind to the creation of a contrived market in gold transactions which entitled it to claim input tax credits upon its acquisitions of scrap gold from the [missing traders]” and that “the applicant facilitated and willingly participated in the round robin arrangement and benefited from the input tax credits that were created”. In coming to its decision on the application of Division 165, the Tribunal appears to have taken a similar approach to that in the United Kingdom – at least at an evidentiary level. The applicant “knew or should have known” that, by its purchase of scrap gold, it was taking part in a transaction connected with the fraudulent evasion of GST. This was sufficient to engage Division 165 as, but for the applicant’s entitlement to input tax credits that flowed from the acquisition of scrap gold, the scheme would not have been entered into. It would appear that it was the applicant’s knowledge that the missing traders were deliberately altering investment grade bullion and were engaged in tax evasion, or wilful blindness to those matters, that gave rise to the relevant “scheme” and elevated the applicant’s entitlement to input tax credits to the dominant purpose, or principal effect, of that scheme. If the missing traders were engaged in the same activities and scrap gold was purchased by an entity who had no knowledge of © Chris Sievers 2020 21 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud those activities and an entity who carried out due diligence into the suppliers, it would appear more difficult to conclude that there was a relevant “scheme” for the purposes of Division 165 and that the applicant’s entitlement to input tax credits to the dominant purpose, or principal effect, of that scheme. Noting of course that the decision is being appealed, going forward, taxpayers would be well advised to undertake due diligence and risk assessment activities over and above being provided with a tax invoice by the supplier and confirming the supplier’s GST registration by undertaking an ABN search. This is particularly the case for low value, high turnover transactions which may be a sign of missing trader fraud. However, such activities may also be prudent for isolated high value transactions where a large input tax credit claim will be made. A guide to the types of activities that may be required is found in the UK Revenue “Fraud” publication discussed above. These activities may include: ▪ Undertaking research on the product and or the market. ▪ Researching suppliers and customers, including company searches to establish trading history and share capital. ▪ Entering into written contracts with suppliers and purchases. ▪ Fully documenting transactions. ▪ Considering the way in which the transaction is to occur and whether there are any unusual or non-commercial elements. © Chris Sievers 2020 22 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud 4 The Commissioner’s administrative approach to “missing trader” fraud As discussed in the introduction, where the parties to a supply chain comply with their obligations under the GST Act, the transaction is revenue neutral for the business participants and the Revenue – with the ultimate consumer bearing the GST cost. Where one entity in the supply chain does not remit GST – for example where the supplier is in financial difficulties - the Commissioner will be exposed financially, as he will still be required to pay input tax credits to the acquiring entity. The Commissioner will be required to seek recovery of the GST from the supplier – for example by proving in the liquidation of the entity as a creditor. That recovery will not impact the entitlement of the acquiring entity to input tax credits. But where the Commissioner forms the view that there may be missing trader fraud, what steps can he take to protect the revenue? ▪ Can the Commissioner seek to collect GST from a supplier while at the same time refusing to pay input tax credits to the acquirer – for example by holding the refund under s 8AALGA of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 while he investigates? ▪ What happens if the missing trader does remit GST or Commissioner successfully recovers GST from the missing trader? Can the Commissioner seek double recovery for the same GST? This appears to be an evolving area, and I expect that the appropriate administrative procedures will be developed over time. Some of the administrative difficulties faced by the Commissioner are illustrated by the recent decision of the Tribunal in Cash World Buyers Pty Ltd and Commissioner of Taxation [2020] AATA 1546. 4.1 Cash World Buyers Pty Ltd and Commissioner of Taxation [2020] AATA 1546 The Tribunal affirmed the decision of the Commissioner to deny the applicant’s claim to input tax credits of $6,936,947.00 with respect to acquisitions of gold during the quarterly tax periods ending 31 December 2014 and 31 March 2015. The disputed claims for input tax credits involved the acquisition (or purported acquisition) of significant amounts of gold from three individuals (referred to by the Tribunal as “Intermediaries”). The applicant satisfied the Tribunal that the acquisitions of gold were made and that the Intermediaries were not acting as agents of the applicant. The real issue before the Tribunal was the form of the gold acquired by the applicant, given that director of the applicant accepted at the hearing that the gold supplied to the applicant by the Intermediaries was sourced from gold bullion dealers and those supplies were treated as input taxed supplies of “precious metal”. The Commissioner submitted that the applicant was not entitled to input tax credits because the applicant purchased gold bullion from the Intermediaries, an input taxed supply. The applicant contended that all of the gold it acquired was “scrap gold” and was taxable. © Chris Sievers 2020 23 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud The Tribunal’s decision ultimately came down to a question of substantiation and documentation. After reviewing the evidence, the Tribunal was not persuaded as to the extent to which the gold acquired by the applicant from the Intermediaries was scrap gold – and was not in bullion form. The Tribunal considered that there many inconsistencies and gaps in the evidence, and some of the evidence was inherently implausible – there were too many shortcomings in the evidence. The Tribunal also made the following observations: ▪ That the applicant was in possession of a document entitled “tax invoice” was not sufficient to prove that a supply was a taxable supply. A tax invoice does not create a taxable supply, it records one. If a taxable supply did not take place, then a tax invoice stating that it did is meaningless ▪ In response to the applicant’s contention that there was no commercial reason for it to pay 105 per cent of the prevailing spot price for gold bullion unless it was required to pay GST to the Intermediaries in respect of the taxable supply of scrap gold, the Tribunal considered that the applicant would have been on notice that subtracting GST from the price paid by the applicant to the Intermediaries left them with approximately 95% of the spot price of gold. Consequently, the Intermediaries would have made a loss of at least 5% each time they supplied gold to the applicant if they were making taxable supplies and remitting GST, as they were themselves acquiring gold bullion for the spot price plus a premium. The Tribunal considered that the applicant could not provide any satisfactory explanation for this proposition. The Tribunal agreed with the Commissioner that the applicant was not entitled to input tax credits because it did not hold valid tax invoices. The Tribunal found that the invoices did not comply with the requirements of s 29-70(1) of the GST Act, nor was this an appropriate case for the tax invoices to be treated as a tax invoice under s 29-70(1B). This was because many of the invoices failed to describe the quantity or weight of the gold supplied and none of the invoices identified any amount of GST payable. All the invoices issued were headed ‘TAX INVOICE*/STATEMENT* (*DELETE AS APPROPRIATE)’ but in none of them had the word ‘STATEMENT’ been crossed out to make clear the document was intended to be a tax invoice. Instead, the invoices were, in the Tribunal’s view, deliberately ambiguous. 4.2 The approach of the Commissioner in the case In the course of the decision, a number of other matters were considered by the Tribunal, albeit the Tribunal was not required to come to a final view. These issues appear to have arisen because of the actions of the Commissioner in issuing assessments of GST to the Intermediaries with respect to the sales of gold to the applicant, while at the same time denying the applicant’s entitlement to input tax credits. 4.2.1 The Intermediaries’ “enterprise” The Commissioner contended that the supply of gold by the Intermediaries to the applicant was not a “taxable supply” because the Intermediaries were not carrying on an enterprise as their activities were © Chris Sievers 2020 24 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud not carried on with a reasonable expectation of profit or gain – as required by s 9-20(2)(c) of the GST Act given that the Intermediaries were individuals. The Tribunal found it unnecessary to explore this submission because of the conclusion that the applicant was not entitled to input tax credits for other reasons, but the Tribunal did observe that this contention was inconsistent with the fact that the Commissioner had earlier instigated the GST registration of one of the Intermediaries and had also issued assessments to each of the Intermediaries for net amounts of GST. The Tribunal also observed that the Intermediaries were registered for GST, so satisfied the building block in s 9-5(d) so as to make taxable supplies. These matters were seen by the Tribunal to be another illustration of the complexity of the issues in the matter. 4.2.2 Division 142 of the GST Act Division 142 deals with the entitlement of taxpayers to recover overpaid GST. Essentially, if a taxpayer has overpaid GST (referred to as “excess GST”), the taxpayer is not entitled to a refund of that GST if the GST has been “passed on” to the recipient and the recipient has not been reimbursed for the overpaid GST. If GST has been passed on, until such time that the recipient is reimbursed, the GST is deemed to have been properly payable: s 142-10. The Tribunal observed that the Commissioner may trigger the application of Division 142 by causing an amount of “excess GST” to be included in a taxpayer’s “assessed net amount” by issuing an assessment even though the GST hasn’t actually been paid to the Commissioner. The applicant contended that by reason of the GST assessments issued to the Intermediaries, this GST was “passed on” to the applicant and even if the Intermediaries did not make taxable supplies to the applicant, the supplies were deemed to be taxable supplies pursuant to s 142-10. The Tribunal considered that the applicant’s difficulty was that it had not demonstrated that the Intermediaries did in fact “pass on” any excess GST to it. The Tribunal found that there was no GST passed on where the prices charged by the Intermediaries did not recover any amount on account of GST. In this regard, it was plainly uneconomic for the Intermediaries to sell gold at prices of approximately 105% of the spot price of gold having purchased the gold from bullion dealers for the spot price plus a margin, in circumstances where they were required to remit GST. Further, the Tribunal observed that if there was excess GST, s 142-15(5) effectively denies the input tax credit if the applicant knew or could be expected to have known that the Intermediaries had not paid the excess GST. 4.2.3 Double recovery The applicant contended that the Commissioner has sought to recover GST from the applicant (by denying input tax credits) and at the same time was seeking to recover GST from the Intermediaries on the basis that they made taxable supplies to the applicant. The Commissioner had issued assessments to the Intermediaries that included the same GST that was being denied to the applicant as input tax credits. It also transpired that the Commissioner had recovered amounts owed by the Intermediaries from third parties pursuant to garnishee orders at the same time as he had sought to deny the input tax credits claimed by the applicant. The applicant © Chris Sievers 2020 25 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud submitted that the assessments were in fact cumulative assessments which were issued contrary to the Commissioner’s stated procedures regarding alternative assessments in the income tax context and impermissibly sought double recovery of GST on the same transactions. The Commissioner adopted the view that he is entitled to issue multiple assessments. Counsel for the Commissioner also submitted that the Commissioner would not seek to recover the GST twice. While not determining the issue, the Tribunal made the following observation (at [225]): Were the Commissioner to succeed against both Cash World and the Intermediaries, it appears that the Commissioner would be in a position to recover the GST amounts twice and, furthermore, may be required to do so without necessarily having a choice in the matter (leaving aside issues with respect to the good management rule and when it is appropriate for the Commissioner to settle tax disputes). In my view, there remains an unresolved issue as to the efficacy of the Commissioner recovering GST amounts twice. However, the double recovery of the GST is not determinative of this dispute and does not give rise to an issue for determination by the Tribunal. The Tribunal appeared to accept that the conduct of the Commissioner could give rise to a double recovery of GST. This begs the question of what the Commissioner’s obligations now are with respect to the GST assessments issued to the Intermediaries (against which objections were lodged but no decision has been made), and the amounts recovered under those assessments pursuant to the garnishee orders. © Chris Sievers 2020 26 Chris Sievers “All that glitters is not gold”: GST and missing trader fraud 5 Conclusion While GST is imposed on each entity that makes a taxable supply within a supply chain, the legislative regime seeks to ensure that the economic burden of the tax is only imposed once - so that there is no “cascading” of GST. This is achieved by the purchaser funding the GST liability of the supplier by paying a “grossed up” price that includes the GST and the purchaser being entitled to claim a refund of that additional amount from the Commissioner by way of an input tax credit - leaving the end consumer (who is not entitled to an input tax credit) to bear the economic burden of the GST. In this context, input tax credits and refunds are an integral part of the GST regime. The entitlement of an entity to an input tax credit is a statutory right as against the Commissioner and the entitlement may crystallise by way of a reduction of the net GST liability payable by the entity or a cash refund payable to the entity. The statutory entitlement to be paid the input tax credit or refund also exists regardless of whether the supplier pays its GST liability to the Commissioner. These matters give acquiring entities certainty as to their ability to recover from the Commissioner the cost of funding the supplier’s GST liability. An issue arises where a supplier fails to pay its GST liability and the Commonwealth is left out of pocket because it has paid input tax credits to the purchaser. Are there circumstances in which the supplier’s failure to pay GST should impact on an acquiring entity’s entitlement to claim input tax credits? The United Kingdom VAT regime has a long-standing approach where an entity is denied the entitlement where it knew or should have known that, by their purchase, they were taking part in a transaction connected with the fraudulent evasion of VAT. Australia has not formally adopted this approach, but the recent decision of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal in ACN 154 520 199 Pty Ltd (in liq) and Commissioner of Taxation [2019] AATA 5981 arguably establishes a regime where a similar outcome may arise by way of the operation of the anti-avoidance provisions in Division 165 of the GST Act. The decision is being appealed to the Federal Court and this will provide the Court with an opportunity to give clarity on the scope of the operation of Division 165 and the circumstances in which an entity’s entitlement to input tax credits may be impacted where a supplier fails to pay GST. What should the Commissioner’s administrative approach be where he forms the view that there may be missing trader fraud. Can he seek to recover GST from the missing trader while at the same time denying input tax credits to the purchaser? How is the question of double recovery to be dealt with? The decision of the Tribunal in Cash World Buyers Pty Ltd and Commissioner of Taxation [2020] AATA 1546 illustrates some of the administrative difficulties faced by the Commissioner. Chris Sievers Lonsdale Chambers Draft - 11 August 2020 © Chris Sievers 2020 27