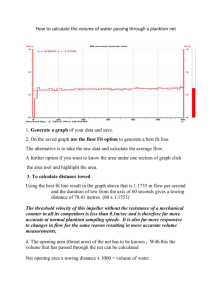

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249282443 Plankton: A Guide to their Ecology and Monitoring for Water Quality Article in Journal of Plankton Research · February 2010 DOI: 10.1093/plankt/fbp102 CITATIONS READS 7 3,758 1 author: Claudia Castellani Plymouth Marine Laboratory 31 PUBLICATIONS 1,027 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Marine Plankton View project All content following this page was uploaded by Claudia Castellani on 10 June 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. JOURNAL OF PLANKTON RESEARCH j VOLUME 32 j NUMBER 2 j PAGES 261 – 262 j 2010 BOOK REVIEW Plankton: A Guide to their Ecology and Monitoring for Water Quality. Edited by Ian M. Suthers and David Rissik, CSIRO Publishing (Australia). 272 pp. ISBN: 9780643090583. AU $49.95 environmental indicator. Chapter 3 presents selected real-life case studies, mainly from Australian coastal waters, which the editors use to illustrate how plankton can be used for monitoring water quality. Consistent and rigorous methodological approaches and appropriate sampling design are key to the success of any environmental survey. Thus, Chapter 4 gives guidelines on the best practice in sampling and monitoring, detailing how to design, implement and conduct meaningful phytoplankton and zooplankton monitoring programs in both marine and freshwater habitats. Accurate identification of plankton, particularly harmful species, can be difficult because many of these organisms are very small requiring skilful microscopy and familiarity with the widely scattered taxonomic literature. Therefore, Chapters 5 – 8, defined by the editors as the “core section” of this book, provide a comprehensive overview of the major freshwater and coastal marine phytoplankton and zooplankton groups. The book closes with Chapter 9 in which the editors consider how the use of mathematical models could aid in forecasting harmful plankton blooms and outbreaks. As the authors point out, the output of most of these sophisticated mathematical models is, however, often controversial because such models cannot replicate the complexity of an ecosystem and it depends on the numerical approach used. They are also difficult to implement requiring mathematical skills very often beyond the reach of many scientists let alone water managers and government officials. Therefore, something which I think is lacking in this book are examples of, simpler but nevertheless useful, numerical methods traditionally employed to investigate changes in community structure and diversity such as biological indices (e.g. Shannon – Wiener index, Pielou’s index) and multivariate analysis. In a book of such wide scope, it is difficult to remain consistent and accurate and this work is not an # The Author 2009. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. For permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oxfordjournals.org Downloaded from plankt.oxfordjournals.org at Bangor University on December 18, 2010 Plankton is of great ecological and economic importance as it is at the base of aquatic food webs and fisheries. Nonetheless, several species of phytoplankton and jellyfish represent a hazard to human health and marine life, as they produce potent toxins or cause other noxious effects, such as anoxia and clogging of fish gills. Over the past century, reports of harmful plankton increases have become more frequent. Although this may be in part attributable to greater awareness of the public and attention from the media, it seems that this increase is real and its cost to the fishing and tourism industry amounts to many millions of dollars per year world-wide. To forecast outbursts of harmful plankton, make plans to avoid their occurrence or control their impact, requires a broad knowledge of the life cycles, ecology and behaviour of these organisms, the ecosystems in which they flourish, and the chemical, physical and biological factors that affect their abundance. To capture the complexity of the plankton within a single book is a difficult and daunting task. There are, in fact, generally very few published books on the ecology of plankton and none to my knowledge that deal with the use of plankton for water quality monitoring. Thus, this concise introductory book edited by Ian M. Suthers and David Rissik represents a useful addition to the existing literature by integrating general aspects of the ecology and taxonomy of key species of marine and freshwater plankton, with technical approaches and methodological guidelines on water quality monitoring. The different chapters draw from the knowledge and experience of a team composed chiefly of Australian scientists and government environmental managers. The book opens with a general introduction on the importance of plankton and the aims of the book. In Chapter 2, the editors provide a concise summary of the ecology of plankton, its associated environmental and water quality issues and its relevance as an JOURNAL OF PLANKTON RESEARCH j 32 VOLUME 2 j PAGES 261 – 262 j 2010 There are also minor points, which would benefit from a thorough editorial revision, starting with the layout of the table of contents [e.g. compare headings 5.4 Bacillariophyceae (diatoms) and 6.2 Diatoms (Division Bacillariophyceae)]. The placement and the use of the figures is also not always appropriate; Figs 6.1, 6.2 and 6.5 representing marine phytoplankton are in Chapter 5 which deals with freshwater phytoplankton, whereas Figs 6.3 and 6.4 are found in Chapter 6. Finally, and yet importantly for the sake of consistency, it would be appropriate to substitute Figs 4.8 and 4.9 (on page 100 and 101) showing a book on insect identification in the background with one illustrating pictures of plankton. Overall, one of the main strengths of this book is its pragmatic and hands-on approach to problem-solving; there are many useful “box” sections throughout the book, which give interesting insights on selected topics and provide practical applications, ranging from the simple calculation of the volume of water filtered by a plankton net, to principles of statistical inferences. The plain language used throughout the book also makes it accessible to a wider audience ranging from “plankton novices”, to non-specialists, managers and students. All in all this represents a nice and concise introductory book, which will be certainly useful to environmental and water quality managers. Nevertheless, the issues highlighted above will need to be addressed in an errata section and eliminated in any subsequent editions for this work to be considered a relevant reference text 262 View publication stats NUMBER Claudia Castellani Sir Alistair Hardy Foundation for Ocean Science (SAHFOS) The Laboratory, Citadel Hill, Plymouth PL1 2PB UK cxc@sahfos.ac.uk doi:10.1093/plankt/fbp102 Advance Access publication November 6, 2009 available online at www.plankt.oxfordjournals.org Downloaded from plankt.oxfordjournals.org at Bangor University on December 18, 2010 exception. As a result, the book is tainted by several inaccuracies and inconsistencies throughout. Thus, below I provide some comments which I think will be helpful for a future a revision and to those interested in this work. On page 65, the “cyclopoid” copepod Oithona spp. has been erroneously reported as a “calanoid” copepod. A number of organisms illustrated in Chapter 8 have been misidentified; for instance, on page 186, Fig. 8.3B, the “phyllosoma” larval stage of the lobster has been misreported as the “pueurulus” stage, which is the settling larval stage, resembling the adult. Again, on page 204, Fig. 8.8, the specimen indicated by “I3” is not an egg mass but it is the nectophore (i.e. the swimming organ) of a siphonophore. The captions of the figures in some of these chapters have missing information and present some inconsistencies. For instance, the tintinnid in C6 Fig 8.8, page 204 does not appear in the caption and the units of the scale bar are missing. The caption of Fig. 8.1 on page 182 is confusing and specimens here have also been misidentified; some of the specimens indicated by the letter “B” are not hyperids but calanoid copepods. In the same figure, the letter “A” indicates “calanoid and cyclopoid copepods”, whereas the letter “F”only “cyclopoid copepods”and the letters “H” and “K” are both used to indicate polychaete larvae. In several parts of the book (i.e. in the text of page 190 and in the box 8.2 on page 193), it is stated that copepods go through six copepodites moults before reaching the adult stage, whereas in reality the 6th copepodite is the adult stage. Other editorial inconsistencies are found on page 203 where it is stated that Noctiluca is “entirely carnivorous” whereas the following sentence reports that “its preferred prey are diatoms” (i.e. phytoplankton). Inevitably, the presence of many contributing authors also gives rise to duplication of information and differences in writing style. The separation of marine and freshwater phytoplankton and zooplankton into four different chapters has resulted in annoying repetitions, as there are elements belonging to these plankton which are common to both environments. j