Birmingham1963

advertisement

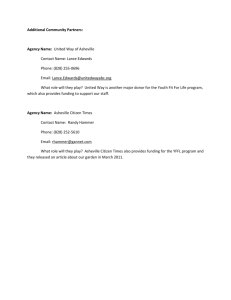

12/4/2013 An Island of Blue Asheville, North Carolina As An Early Progressive Bastion in Jim Crow’s South Richard Curley HISTORY 341, HISTORY OF NORTH CAROLINA Today, Asheville, North Carolina enjoys a reputation as one of the most progressive cities in the United States. In fact, Asheville has such a progressive reputation that it is referred to by many as the “San Francisco of the South.” This progressive attitude is not a recent development for Asheville. In fact, it can be seen reflected in the coverage of one of the seminal tragedies of the civil rights movement, the Birmingham church bombing of 1963, in Asheville’s local paper, The Asheville Citizen. This coverage more closely resembled the desired response, of civil rights organizers, of the national press than the response of a local paper in Jim Crow’s south. Following the unsuccessful civil rights campaign in Albany, Georgia from 1961 to 1962, the organizers of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference came to the realization that a change in strategy was needed. During and prior to the Albany campaign, the SCLC had followed a strategy of persuasion. Their goal had been to try and persuade their opponents that segregation was wrong and needed to be changed. This strategy garnered little press coverage and even fewer results, particularly in Albany, where the local leadership ensured that there was little to no violence against demonstrators.1 What the SCLC realized was that the best way to garner attention from the national press and support from the federal government was to be on the receiving end of unprovoked violence. Albany had demonstrated that no violence equaled no national attention and no national attention equaled no concessions. National attention was needed in order to persuade those who were either undecided or ambivalent to the evils of segregation and thus bring greater pressure against the system of segregation. The SCLC needed to show the maliciousness and senselessness of 1 Fleming Cynthia Griggs, In the Shadow of Selma (New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2004), pg. 150 segregationist violence. Moreover, they needed this violence to speak to the more progressive elements in society to achieve the goal of ending segregation.2 Segregation could not end without ceasing to be seen as a regional issue, it must be seen, for what it really was, a national issue. Without extensive and sympathetic national press coverage this would not be possible. The SCLC chose to participate in the Birmingham campaign, specifically, for its history of violent opposition to the civil rights movement. Birmingham represented the worst face of southern racism and its violent opposition to change. Martin Luther King, Jr. even stated that “if we can crack Birmingham, I’m convinced we can crack the south.”3The SCLC’s campaign in Birmingham would lead to both one of the movement’s greatest triumphs and greatest tragedies. By the end of the campaign the movement would achieve the transformation of segregation into a national issue and the passage of both the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Birmingham civil rights campaign was marked by significant levels of violence throughout. Eugene “Bull” Connor, Birmingham’s Commissioner of Public Safety, lived up to his reputation, and unleashed a wave of violence upon peaceful demonstrators. These actions created a large amount of media coverage both nationally and internationally. Connor’s use of dogs on the demonstrators provided front page photos for numerous papers around the world. The actions of Connor and the rest of Birmingham’s leadership would indeed garner the necessary national sympathy and federal attention to force concessions.4 However, the action that 2 Garrow, David J., Protest at Selma: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1978), pg.2 3 Fleming, pg.150 4 Garrow,pg.168 would outrage the national conscience, to a degree never before witnessed, and enough to demand federal action would actual take place as the result of these concessions.5 The event that so stirred the national conscience and cost four little girls their lives happened early Sunday morning on September 15, 1963. On that day in September, at 10:22am the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was bombed, resulting in numerous injuries and the deaths of four young girls. This bombing shattered the false sense of relief felt by many in Birmingham, following the first, relatively peaceful, week of school integration in the city. The bombing also touched off violence throughout the city that left two more black youths dead and many more citizens, black and white, injured. It gave the national media a seminal event with which to show the hideous and horrifying nature of segregationist violence, which in turn created the necessary political pressure to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964. 6 The national media quickly condemned the bombing and placed the blame squarely on the forces of segregation. One article blamed it on the “long-steeping racism of Birmingham’s whole seamy past” and the climate created by George Wallace through his defiance of the law and courts.7Moreover, the response to the ensuing violence was criticized, particularly the fact that only black crowds were dispersed, while whites were allowed to freely congregate.8One article in Newsweek, published shortly after the bombing, noted that Saturday was day that everyone had anticipated violence. It also offered a telling quote about how the supporters of segregation were perceived outside the south. Saturday was “a dangerous day when rednecks 5 Mendelsohn Jack, The Martyrs: Sixteen Who Gave Their Lives For Racial Justice (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1966),pg.103 6 Ibid, pg.103 7 Carson, Clayborne, et al., Reporting Civil Rights Part 2: American Journalism 1963-1973 (New York: The Library of America, 2003), pg.28-29 8 Ibid, pg.29 with nothing much to do would tank up in jook joints.”9This quote, without saying it directly, clearly places the blame for the fear and violence on the segregationists and places them outside the norm of society. The Asheville Citizen, unlike many southern newspapers, coverage was very much in line with the national coverage. The paper ran many headlines and front-page articles concerning the bombing and its aftermath, directly from the AP, without change or editorial comment, with one notable exception. They also printed a number of editorials and letters to the editor concerning the events that were critical of the actions of the white supremacists and leadership in Alabama. It is true that not all the letters to the editor were critical of the segregationists and elements of paternalism appear in some editorials. However, when taken as a whole the coverage of the paper shows little of the regressive nature of the Jim Crow south it and its city were a part of. Ironically on the day of the bombing, The Asheville Citizen, ran a reprint of an AP article that spoke of the lack of violence during the previous week. “Despite the frightening violence which preceded the breakdown of racial barriers in Birmingham and which authorities grimly expected to continue, there have been no bombings, no gunfire, no angry mobs roaming the streets since Negro students went to class at once white schools.”10Moreover, it noted that school attendance at these newly desegregated schools was 85% of normal and that the students were well behaved, with things only getting rough when parents became involved. Finally, and perhaps most telling, the article used the term race-baiting, to describe the activities of the 9 Ibid,pg.27 Thomas, Rex. “Many Alabama Students Go Along With Integration.” Asheville: Greeneville-News Piedmont Company, 09/15/63. WCU Collection. 10 National States Rights Party11. Given the negative connotations of such a term as race-baiting, the fact this term was not edited out of the AP article by the paper can be seen as evidence of progressive leanings. Also that day there appeared an editorial in The Asheville Citizen that was, for a southern paper, surprising critical of the Alabama Governor, George Wallace. This editorial accused Wallace of using state troops to usurp local authority, when he tried to deny the first AfricanAmerican students access to their new schools. Wallace’s actions had violated his own pledges to fight to enforce, not only the State’s rights, but the rights of the local communities and the individual citizens of Alabama. An argument very similar to those made by many in western North Carolina against the Confederacy and Governor Vance, during the civil war. Moreover, it labeled Wallace as a coward only concerned with the bolstering of his own, self-made, image. Wallace’s only accomplishment was to create a harmful view of Alabama and flee from a confrontation with President Kennedy.12 The day after the Birmingham bombing, The Asheville Citizen headline for the day read “Four Negro Children Die in Birmingham Bombing” under the caption “MORE UNREST FORESEEN.” 13This headline was accompanied by a photo of some of the bomb damage to the surrounding neighborhood. Moreover, the front page contained the headlines accompanying article and another article. The second article was entitled, “Lesson Title Quite Ironic: Studies Twisted Into Terror, Death” a reference to the Sunday school lesson the girls had heard that 11 Thomas, Rex. “Many Alabama Students Go Along With Integration.” Asheville: Greeneville-News Piedmont Company, 09/15/63. WCU Collection. 12 The Asheville Citizen, “Wallace Stages an Inglorious Retreat.” Asheville: Greeneville-News Piedmont Company, 09/15/63. WCU Collection. 13 The Asheville Citizen, “Four Negro Children Die in Birmingham Bombing.” Asheville: Greeneville-News Piedmont Company, 09/16/63. WCU Collection. morning, The Love that forgives. A passage from this article states, “Who knows on what part the four Negro children were reading when their bodies were hit by flying glass and mortar? Maybe they had reached the end of the lesson, with a passage from Matthew: “But I say unto you, love your enemies.”14A rather poignant way to emphasize the innocence of the victims, and to point out the malice of the perpetrators. The headline article from September 16th continues on page two of the paper and it contains an interesting change to the headline of the article. The column of the continued article has a new headline. Whereas on the front page it contains the phrase, “Four Negro Children” on the continuation, this is changed to simply “4 Children Die In Church Blast.”15 This may seem a slight change, but in reality, it conveys a sense of shared humanity, and that it is superfluous to delineate race when it comes to the death of a child. On September 17th, the paper’s headline, once again, was about the bombing in Birmingham. This headline read “Negro Leaders Call For Federal Troops” with an accompanying article from the AP and a photo of an integrated group of school children returning to school.16 There was also a second front page articles concerning a planned march on Montgomery to protest the bombing. This article was also an AP reprint, but as with previous AP reprints, it was not edited by the paper and contained a couple of quotes critical of Governor Wallace and the federal government. “If the Federal Government had done its job Gov. Wallace 14 Purk, Jim. “Lesson Title Quite Ironic.” Asheville: Greeneville-News Piedmont Company, 09/16/63. WCU Collection. The Asheville Citizen, “Four Negro Children Die in Birmingham Bombing.” Asheville: Greeneville-News Piedmont Company, 09/16/63. WCU Collection. 16 The Asheville Citizen, “Negro Leaders Call For Federal Troops.” Asheville: Greeneville-News Piedmont Company, 09/17/63. WCU Collection. 15 would be in jail right now” and If the government had done its job…the 16th Street Baptist Church would not be a bombed Church.”17 Both front page articles from September 17th contain quotes or information critical of the white leadership at the federal, state, and local levels. However, this did not stop The Asheville Citizen running the articles as is, or from running a headline drawing attention to those articles. The paper chose not to shy away from articles critical of the violence, its perpetrators, or the response to it. This gives the impression that there was not a fear of a significant backlash from their readership or that its circulation would be hurt by its coverage. Throughout the rest of the week after the bombing the paper would continue to run reprints of AP articles concerning the bombing and its aftermath. Although several of these would be on the front page, there would be no more headlines. This does not mean that the paper ignored the situation or that it was backing off its coverage. In fact, it was during this time that they published the one and only editor’s note to an article on the bombing. The editor’s note was for an article by Jules Loh, entitled “What’s in Store for Birmingham, A City That Spawn’s Disorder? The note reads, “Racial violence in Alabama reached a sickening peak Sunday when four children were killed by a bomb. What is the deep-seated situation in a city which seems to spawn disorder? Here is a penetrating look at what has passed and a glimpse of what may be in store for Birmingham.”18 17 The Asheville Citizen, “March On Capitol Planned At Rally In Birmingham.” Asheville: Greeneville-News Piedmont Company, 09/17/63. WCU Collection. 18 The Asheville Citizen, “Editor’s Note.” Asheville: Greeneville-News Piedmont Company, 09/22/63. WCU Collection. The article for which the Editor’s Note was written is one that is highly critical, not only the perpetrators of the violence, but of Birmingham’s white residents and white establishment. While the article places blame for some of the issues facing Birmingham on forces outside the control of the average white resident, it does not exonerate them. Saying of Birmingham’s whites residents after the bombing, “it is certainly true today that while the Negro’s search in this city is upward, the white man’s is inward.”19It would be hard to imagine that an editor for a newspaper in Alabama or Mississippi, would have been willing to draw attention to such an article. Particular, one that so clearly points out that the need for soul searching, fell not on the opponents of segregation and segregationist violence, but on its perpetrators. On its editorial pages during the first week of the bombing, The Asheville Citizen, had only two editorials. One of these was a national columnist, William S. White, and though critical of Alabama, offers more of a glimpse into “Old South” paternalism, with an interesting twist. The other editorial was from the paper’s editorial staff. This editorial exhibited none of the qualities of “Old South” paternalism and does not shy away from affixing blame for the tragedy. On September 17th, the paper published its editorial, “Hate Exacts A Price in Troubled Alabama,” addressing the tragedy in Birmingham and pulls no punches in affixing blame. First and foremost, the editorial acknowledges the human toll of the tragedy and its aftermath, with four killed and 23 injured in the bombing and two more killed and scores more injured in the aftermath. Secondly, it does not blame the Civil Rights protesters, it blames political demagogues, the White Citizens Councils, police authorities, and others in official positions. In 19 Loh, Jules. “What’s In Store For Birmingham, A City That Spawns Disorder.” Asheville: Greeneville-News Piedmont Company, 09/22/63. WCU Collection. fact, it calls Governor Wallace “the most assiduous tiller”20 of the seeds of racial hatred. Moreover, it also blames Alabama’s newspapers for assuming Governor Wallace’s stand on segregation and stoking racial hatred. Finally, it laments the silence of the responsible leadership of the state and hopes the tragedy spurs Alabama’s moderates and business leaders to take an active role in restoring reason. “Hate Exacts A Price In Troubled Alabama” pulled no punches in its critique of the situation in Alabama and the causes of the Birmingham bombing. Furthermore, it does not fall into the time tested tactic of blaming the victim, which was the case in many areas in the south. In fact, it acknowledges the innocence of the bombing victims. Moreover, it directly names and holds responsible, Governor Wallace and the White Citizens Councils, a man and a group rarely, if ever, vilified within Jim Crow’s south. In contrast to the editorial staff’s editorial, William S. White’s editorial, published on September 20th, and entitled “Alabama Hurts South’s Cause,” shows little progressive qualities. As its title suggests, Mr. White, is not an avid opponent of segregation. In fact, Mr. White sees the ending of segregation on private property as a matter of choice and that it is the South’s duty and cause to resist the more extremist aspects of the civil rights agenda. It is his feeling that ground should only be given gradually in the name of ordered freedom. In other words, we see a repeat of the “too far, too fast” argument of paternalism. By resorting to violence, the people of Alabama have brought emotion into the issue and only gave power to the extremist in the civil rights movement. However, there is one point that Mr. White makes that differs from “Old 20 The Asheville Citizen, “Hate Exacts A Price In Troubled Alabama.” Asheville: Greeneville-News Piedmont Company, 09/17/63. WCU Collection. South” paternalism, he acknowledges that voting is a right and that steps should be taken to “vindicate actual negro rights.”21 This editorial, even with its acknowledgment that African-Americans have certain, if not the same as whites, rights differs starkly from the editorial from the staff of The Asheville Citizen. Unlike The Asheville Citizen’s editorial, Mr. White fails to truly acknowledge the horror of the bombing and does not mention its human cost. Rather, than lamenting the death of six innocent people and the injuries to numerous others, it laments the injury to a cause marked by hatred and violence. In essence, Mr. White is trying to remind the forces of white supremacy to remember Albany, Georgia and forget about Birmingham. When comparing Mr. White’s editorial, with the editorial of The Asheville Citizen, the progressive nature of Asheville and its paper becomes much more evident. Along with its articles and editorial, The Asheville Citizen’s and Asheville’s progressive nature can be seen in its letters to the editor. Although in the week after the bombing there were only two letters that were published, these letters offer a glimpse into Asheville’s character of the time. Moreover, the papers printing of the letters, both of which were of a progressive bent, were not accompanied by the editorial and public vitriol that accompanied such letters elsewhere. The first letter to the editor was published on September 18th, and was written by Edwin Michael Hoffman. Mr. Hoffman’s letter was written as a refutation of speech by Alabama’s Governor Wallace after the bombing. In his speech Mr. Wallace compared the events of Birmingham to past events in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In his letter, Mr. Hoffman refutes Governor Wallace’s speech point by point throughout his letter and points the blame back at 21 White, William S. “Alabama Hurts South’s Cause.” Asheville: Greeneville-News Piedmont Company, 09/16/63. WCU Collection. Birmingham’s segregationists for the violence. Mr. Hoffman closed his letter by stating that “Philadelphia’s crimes” cannot be used to exculpate any Birmingham violence” and compares the efforts in Birmingham and the attacks on them to the attacks on St. Paul and the early Church.22 The second letter to the editor was published on September 20th, and was submitted by Allen Dillon. This letter was short and dealt with the need for better cooperation between the north and south. It points out that both regions have their problems and included in those is race relations. The letter states that the only way for these problems to be overcome is for the both sides to forget the Civil War and live together as Americans. Although it seems a fairly innocuous letter, the fact acknowledges the need to forget the differences between regions is important. It again shows a progressive leaning not often found in the South of the 1960’s or earlier. These letters to the editor were published without comment from the editorial staff. Moreover, they were not answered with the violent and hateful reaction that similar letters received elsewhere. One case in particular that stands out is the response to a letter sent to and published by The Birmingham News, shortly after the bombing. In this letter, a female resident of Birmingham questioned the Christian faith of segregationists and the bombers of the Church. In response to this, the paper, printed, not only her name, but her address. The author of the letter 22 Hoffman, Edwin W. “Philadelphia Riot Unlike Birmingham.” Asheville: Greeneville-News Piedmont Company, 09/16/63. WCU Collection. was then subjected to numerous threats of violence in the paper and over the phone and her home was repeatedly vandalized.23A reaction that did not happen in Asheville. It should be said that during the week after the Birmingham bombing, that The Asheville Citizen did not only publish articles concerning the civil rights efforts in Alabama. The paper also published numerous articles about efforts in North Carolina. Much as with the Birmingham bombing, many of these were reprints of AP articles, but a few were by local writing staff. That being said they showed the same willingness to publish facts without interpretation or condemnation. This can be seen as yet more evidence of the paper’s and its reader’s progressive nature. Of course, we cannot take the absence of printed vitriol or items critical to the civil rights movement, to deny the existence or support for segregation and white supremacy. The fact remains that, contrary to perceptions, there is no, nor has there been, a homogenous community opinion on this, or any other national issue. However, what we can say is that the reaction to the Birmingham campaign, bombing, and its coverage in The Asheville Citizen, was of a decidedly different character than past events, in which race played a prominent part. Absent were articles praising the defenders of white supremacy and cartoons lampooning African-Americans. No articles or editorials lamenting the growing political power of African-Americans and warning whites of their own impending subjugation appeared. This absence, along with the actual coverage of events, can be seen as demonstrable evidence of progress, particularly since the days of Reconstruction and Fusion politics. 23 Mendelsohn, pg.100 In the terms of modern political discussion, Asheville and other parts of Western North Carolina can be seen as an island of blue in the sea of red that marks the South. The coverage of The Asheville Citizen and both the response and lack of response from their readership to the Birmingham Bombing in 1963, shows that this was much the same case then. When reading the articles, editorials, and letters, terms and opinions appear that today may not seem appropriate or denote a progressive world view. However, they must be considered in the context and the time they were written in. By the standards of 1963, Asheville and its hometown newspaper demonstrated a world view that was indeed progressive and set them apart as an island of blue in a sea of red.