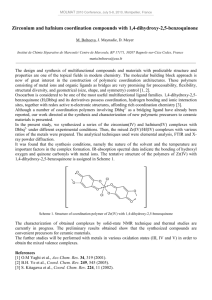

pubs.acs.org/acscatalysis Perspective Redox-Active Ligands in Electroassisted Catalytic H+ and CO2 Reductions: Benefits and Risks Nicolas Queyriaux* Cite This: ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4024−4035 Downloaded via NORTHWEST NORMAL UNIV on May 2, 2021 at 10:32:42 (UTC). See https://pubs.acs.org/sharingguidelines for options on how to legitimately share published articles. ACCESS Read Online Metrics & More Article Recommendations ABSTRACT: In the past decade, the use of redox-active ligands has emerged as a promising strategy to improve catalyst selectivity, efficiency, and stability in electroassisted H+ and CO2 reductions. Partial delocalization of the electrons within ligand-centered orbitals has been proposed to serve as an electron reservoir, as a catalytic trigger, or as a way to prevent deleterious low-valent metal center formation. However, conclusive evidence of these effects is still scarce, and open questions remain regarding the way redoxactive ligands may affect the catalytic mechanism. In this Perspective, advances in redox-active ligands in electroassisted catalytic H+ and CO2 reductions are discussed through recent representative examples. KEYWORDS: ligand design, redox-active ligand, electroassisted catalysis, hydrogen evolution, carbon dioxide reduction 1. INTRODUCTION Owing to its ability to drastically decrease the addiction of our modern societies to fossil resources, the electrochemical conversion of abundant feedstocks, such as H2O or CO2, into fuels or commodity chemicals has emerged, in the last decades, as one of the most promising solutions offered by the academic world to the urgent energy and environmental imperatives. As simple as they may look on paper, these transformations are complex. They involve multielectron, multistep processes and generally require the assistance of catalytic systems to reduce energy requirements and to increase selectivity. The ability of transition-metal complexes to exhibit various oxidation states in a relatively limited range of potential and their by-design adjustable properties have contributed to their emergence as an important class of electrocatalysts. When reductive processes are considered, these complexes thus accept electrons under an application of cathodic potential. Nevertheless, where are the electrons hosted? Are the electrons located on molecular orbitals that display a strong metal character or on ligand-centered orbitals? Are they highly delocalized, lying in extensively mixed molecular orbitals? These questions are of great importance for those who wish to better understand the mechanism underlying the catalytic process. Answering these questions may also provide insights regarding the nature of the deactivation pathways specific to the catalyst under study. In recent years, a large and still-growing body of work has been dedicated to electrocatalysts displaying redox-active ligands, either for hydrogen evolution or CO2 reduction. Among the ligands that are able to store part of the © 2021 American Chemical Society supplementary electron density upon reduction of a coordination complex, the most commonly encountered in electroassisted reductive processes are polypyridines,1−4 iminopyridines,5−7 and other nitrogen-based heterocycles (quinoline,8,9 pyrazine10,11). Phthalocyanines,12−15 corroles,16,17 and porphyrins18−20 are also key ligands to build robust, efficient, and stable electrocatalysts. Contradictory data are available in the literature concerning the involvement of redox events located on ligandcentered orbitals over the electroassisted reduction of CO2 and proton by their metal complexes (usually Fe and Co).21−26 In the absence of a clear consensus, such compounds will thus not be discussed further in this Perspective. Different motivations have been invoked to explain the use of redox-active ligands, from their role as electron reservoirs to their potential ability to increase selectivity or stability.3,27−33 In some rare cases, catalytic mechanisms relying only on ligandcentered processes have been observed, the role of the metallic ion being dramatically decreased. However, the effect of the redox moiety within the ligand framework is often difficult to conclusively demonstrate. It is indeed challenging to draw relevant comparisons between complexes, depending on whether they display such motifs or not. Beyond the apparent Received: January 17, 2021 Revised: March 5, 2021 Published: March 16, 2021 4024 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00237 ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4024−4035 ACS Catalysis pubs.acs.org/acscatalysis Perspective should also be noted that catalytic systems with a redox-active ligand commonly favor the formation of carbon monoxide, in comparison to that of formate.1,5,43,44 The formation of formate usually being triggered by the insertion of CO2 into a metal− hydride bond, the elimination of hydride-type reaction intermediates seems to be at work here as well. Rather than only enhancing the selectivity of CO2 reduction over that of protons, an approach that mitigates the metal center nucleophilicity is thus a powerful tool to favor the formation of a single C1 product. 2.1.1. Example 1: Bipyridyl-N-heterocyclic Carbene Donors As Redox-Active Ligands. In a recent study, Jurss, Panetier, and co-workers have investigated the electrocatalytic behavior of a series of nickel complexes featuring bipyridyl-N-heterocyclic carbene ligands (complexes I.1−3, Figure 1).28 These ligand benefits, a number of studies have also highlighted the occurrence of deactivation processes and decomposition mechanisms specific to redox-active ligands. Dearomatization, radical-driven reactivities (carboxylation, carbonation), and electron trapping within ligand-centered orbitals or weakly activated catalytic intermediates are among the most commonly met deleterious side reactions.6,34−38 Understanding the effects of redox-active ligands on electrochemically driven catalytic processes can help in the rational development of more efficient catalysts. To this end, this Perspective examines molecular catalysts that include such motifs in the context of electroassisted proton and CO2 reduction. Section 2 will be dedicated to the positive effects that redox-active ligands may have on catalytic proton and CO2 reduction processes. Section 3 will explore their deleterious consequences. Each section will be exemplified by recent ad hoc developments from the literature. On the basis of these analyses, some general guidelines will finally be proposed to inspire the design of efficient catalysts bearing redox-active moieties for electroassisted fuel generation. 2. BENEFICIAL EFFECTS OF REDOX-ACTIVE LIGANDS ON THE ELECTROCATALYTIC BEHAVIOR The assessment of an electrocatalyst’s performances relies on a number of factors of merit. Some of the most commonly considered are (i) the selectivity (i.e. the ability of the catalysts to drive the formation of a unique product, usually described by close-to-unity Faradaic yields), (ii) the overpotential requirement (i.e. the difference between the reaction thermodynamic potential and the potential at which the catalytic event is effectively detected, typically denoted η and measured at the midwave potential39,40), (iii) the turnover frequency (i.e. the rate at which the complex performed a given catalytic cycle), and (iv) the stability (i.e. the durability of the catalysts under working conditions, commonly described by the turnover number or TON). Should the introduction of a redox-active moiety in the ligand scaffold have any positive effect, a significant improvement of at least one of these parameters should be noticed without substantial worsening of the others. In the following paragraphs, we have sought to identify a collection of catalytic systems for which the use of redox-active ligands resulted in clear benefits. 2.1. Increasing Selectivity. In the course of electroassisted CO2 reduction, product selectivity may represent quite a challenge. Contributing factors include the variety of chemicals that can be generated in a fairly narrow range of potential (CO at −0.53 V vs NHE, HCOOH at −0.61 V vs NHE, HCHO at −0.48 V vs NHE, CH3OH at −0.38 V vs NHE, CH4 at −0.24 V vs NHE41) and the competitive reduction of protons to H2 (at −0.42 V vs NHE42). Mixtures of two-electron-reduction products (CO/HCOOH/H2) are frequently encountered with electroassisted molecular systems, calling for a rationalization of the parameters enabling selective systems to be accessed. In the absence of a redox-active motif, most of the electronic density gained from the reduction processes is located at the metal center. The associated Lewis basicity buildup has typically been reported to favor metal hydride formation.28,29 Such reactivity is a major step on the path to proton reduction. Electron capture in ligand-based orbitals thus appears promising because it is expected to substantially lower the nucleophilicity of the metal center, thereby disfavoring the hydride pathway. This strategy results in an increase in the selectivity of CO2 reduction in comparison to that of protons. For an identical metal center, it Figure 1. Structures of the nickel complexes I.1−3. scaffolds, when they are macrocyclic, display variable lengths of the alkyl bridging group. An increased rigidity of the redox-active macrocycle leads to significant structural constraints: whereas complex I.1 adopts a distorted-tetrahedral geometry, squareplanar environments are observed in the case of two other complexes. Such a structural shift is expected to significantly affect the electronic structure of the different complexes. Interestingly, the authors were able to draw a clear trend between the degree of rigidity of the ligands, the electronic structures of the one- and two-electron-reduced complexes and their ability to efficiently drive the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2. After two reductions, the non-macrocyclic complex I.1 is characterized by a nickel(I) center associated with a monoreduced ligand. In contrast, the doubly reduced complex I.3 exhibits a virtually unchanged nickel(II) center supported by a biradical ligand. DFT calculations suggest an intermediate electronic structure between these two limiting forms, for complex I.2. These results should be compared with improved Faradaic yields for the CO2-to-CO conversion observed throughout the series: 5% (I.1), 56% (I.2), and 87% (I.3). The authors propose that the increasing difficulty in generating nickel hydrides from the reduced states along this series is the main reason for the observed selectivity improvement. The study of this ligand set was then extended to analogous cobalt(II) complexes, with similar results.29 Within this new series of compounds, the importance of a balanced distribution of the electron density between the metal center and the redoxactive ligand was highlighted: the metal must acquire sufficient nucleophilicity to allow further formation of a CO2 adduct, but an excessive increase in the Lewis basicity promotes hydrogen evolution. 2.1.2. Example 2: Functionalized Terpyridines As RedoxActive Ligands. Very recently, Chang and co-workers have 4025 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00237 ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4024−4035 ACS Catalysis pubs.acs.org/acscatalysis Perspective Figure 2. Structures of the iron complexes I.4 and I.5 and their simplified molecular orbital diagrams. 2.2. Decreasing Overpotential Requirement. Reducing protons to hydrogen, such as reducing CO2 to CO or formate, requires two electrons that temporarily transit on the catalyst. Various sequences of events may be considered, depending on the catalytic mechanism (EECC, ECEC, and ECCE as examples, where E corresponds to an electron transfer step and C to a chemical reaction).46 In a number of situations,18−20,47−49 catalysts have to be able to successively accommodate two supplementary electrons. To be energy-efficient, those electrons should be transferred at balanced electrode potentials: cathodic enough to overcome the kinetic barrier but as close as possible to the thermodynamic equilibrium. However, it can sometimes prove challenging to generate the required low-valent metal species (cobalt(0) or iron(0), as examples) at potentials that are not excessively negative. In this context, the introduction of new redox events, centered on the ligand scaffold, may appear as an appealing alternative to trigger catalytic processes at valuable potentials. On initiation by ligand-centered processes, it is advantageous to tailor the ligand’s redox properties through proper ligand design (introduction of electron-withdrawing groups and use of extended π-conjugated ligands displaying low-lying π* orbitals as examples) to lower the energy requirements. In such situations, most authors generally find themselves dealing with scaling relationships: decreasing the catalyst overpotential leads to a slowdown of the catalytic process.50,51 The reverse also holds true, resulting in middle-ground compromises. 2.2.1. Example 3: Combining Strong σ-Donor Ligands and Redox-Active Ligands to Break Scaling Relationships. To avoid compromising between high catalytic rates and low overpotential, Miller and co-workers recently proposed a strategy to decouple electronic tuning of the metal center nucleophilicity and catalyst redox potentials.30,52 In this context, the authors have examined the electroassisted reduction of CO2 by two geometric isomers of a ruthenium complex with the general formula [Ru(tpy)(Mebim-py)(NCCH3)]2+ (tpy = 2,2′;6′,2″-terpyridine, Mebim-py = 1-methylbenzimidazol-2ylidene-3-(2′-pyridine)). These isomers display either the carbene donor53,54 or the pyridine donor trans to the acetonitrile ligand (complexes I.6 and I.7, Figure 3). The initial measurements revealed similar electrocatalytic properties for both complexes in terms of selectivity, overpotential, and catalytic activity. Using high-scan-rate voltammetry, the authors evidenced a two-electron ligand-based reduction that is able to induce isomerization of complex I.7 to I.6 by rapid dissociation of the acetonitrile ligand. An in-depth mechanistic understanding was achieved by the preparation of catalytically relevant intermediates that were thoroughly examined by the means of electrochemical tools. When they were taken together, investigated electrochemical CO2 reduction assisted by an iron(II) complex, displaying a pentapyridine ligand based on a redox-active terpyridine motif (complex I.4, Figure 2).27 In the presence of an excess of phenol (3.5 M) under an atmosphere of CO2, large current enhancements were observed on the voltammetric scale in acetonitrile. Bulk electrolysis experiments were performed that ensure the catalytic nature of the process: Faradaic yields as high as 94% for CO2-to-CO conversion were determined at a 190 mV overpotential. Under identical conditions, the iron complex I-5 (Figure 2)structurally related but lacking a redox-active motifproved unable to drive CO2 reduction and mostly displayed proton reduction activity. In order to gain further insight into the remarkable properties of this catalytic system, the authors have undertaken the preparation and characterization of the two-electronreduced species that is believed to be crucial to the catalytic cycle. Generated by chemical reduction, this complex has been exhaustively characterized, revealing an iron(II) center (featuring the intermediate-spin SFe = 1) supported by a doubly reduced polypyridine ligand (biradical in nature and displaying a triplet character, SL = 1). As they are antiferromagnetically coupled, these two components result in an open-shell singlet ground state. Such an electronic structure, which promotes strong metal−ligand cooperativity, is proposed as a convenient way to limit hydrogen evolution pathways (i.e. by disfavoring metal hydride formation), resulting in high selectivity toward CO2 reduction. In a related study, the competition between electroassisted reduction of protons and CO2-to-CO conversion in the presence of cobalt(II) terpyridine complexes has been studied by Fontecave and co-workers.45 In the presence of a proton source under an inert atmosphere, the authors were able to determine the rate constants associated with proton reduction for a series of complexes displaying terpyridine functionalized with either electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups. A clear trend emerged: the more electron withdrawing groups led to decreased rate constants toward H2 evolution. Interestingly, when the competitive CO2-to-CO pathway was enabled by saturating the electrolytic solutions with carbon dioxide, a related trend was noticed: the more electron-withdrawing groups led to an increased Faradaic yield for CO production. In light of previous discussions, it is tempting to assign such behaviors to a decreased contribution of the metal-centered orbitals in the reduced form of the complexes. This would thus result in a lower nucleophilicity of the cobalt center and disfavor the formation of hydride derivatives. By fine-tuning the degree of redox activity of the terpyridine ligands, it thus appears possible to slow down catalytic pathways resulting in hydrogen evolution to enhance selectivity toward CO2-to-CO reduction. 4026 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00237 ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4024−4035 ACS Catalysis pubs.acs.org/acscatalysis Perspective of studies have been dedicated to metal dithiolene32,58−61 and metal thiosemicarbazone33,62−64 complexes. The former initiated early works on redox-active ligands, due to the inability of conventional oxidation-state descriptors to provide a satisfying depiction of their electronic structures.65 A recent review by Mitsopoulou and co-workers comprehensively surveys the different electro- and photocatalytic behaviors of representative members of this wide family of compounds.58 Although distinct mechanisms have been proposed, depending on the nature of the dithiolene derivatization, the most commonly encountered electrocatalytic pathways rely on an ECCE sequence (where E corresponds to an electron transfer step and C to a chemical reaction, here protonation). The reduction of the redox-active ligand allows two successive protonations of the ligand framework. A last reduction yields a doubly protonated two-electron-reduced species from which H2 typically evolves (complexes I.8M, Figure 4).32,59 2.4. Introducing New Catalytic Pathways. Redox-active ligands disrupt the usual electron distribution within catalysts. In reduced states, the metal center is no longer a potent nucleophile capable of independently initiating reactions with substrates. The increased electron density located on the ligand scaffold may trigger mechanistic events whose occurrence is otherwise not observed. Hence, Waymouth, Sarangi, and co-workers were able to prevent the electroinduced dimerization of a manganese(I) tricarbonyl complex by the introduction of an azopyridine derivative as a ligand.66 Direct formation of the two-electronreduced mononuclear complex was evidenced, bypassing the redox-reluctant manganese dimer.67,68 A similar disfavoring of dimer formation was observed by Kubiak and co-workers when bulky tBu groups were used to induce metal-directed steric hindrance.68 To another extent, Mulfort and co-workers have considered intramolecular electron and proton transfers between a cobalt center and its redox-active ligand, as part of Figure 3. Structures of the ruthenium complexes I.6 and I.7. the data pointed out a “reduction first” pathway, excluding the intermediate formation of metal hydrides. According to the authors, the high activity of the catalystobserved at mild overpotentialresults from two main effects: (i) the use of carbene as a strong σ-donor ligand allows a sufficiently high nucleophilicity of the metal center to be reached, even when most of the acquired electron density is located on the ligand orbitals, and (ii) the presence of a redox-active motif triggers the catalytic process at a lower overpotential. Further studies have quantitatively investigated the effects of the redox-silent carbene moiety on electroassisted CO2 reduction, highlighting its important role in catalyst isomerization and ligand substitution processes.55 2.3. Enhancing Local Concentration of Protons. The introduction of basic sites capable of virtually increasing the local proton concentration near the catalytic site is a robust strategy for improving catalyst performances toward proton-assisted multielectron processes, such as proton reduction56,57 and CO2 reduction.18 As such, redox-active ligands are interesting motifs. Indeed, the additional electronic density acquired during their reduction significantly boosts their basicity. Initially poorly basic positions then become proton-responsive and may therefore function as proton relays. Among the catalytic systems that typically promote ligand protonation upon reduction, a number Figure 4. Proposed ECCE mechanism for H2 evolution catalyzed by complexes I.8M (M = Co, Ni). 4027 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00237 ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4024−4035 ACS Catalysis pubs.acs.org/acscatalysis Perspective Figure 5. Structures of the cobalt complexes I.9−11. assessed, on the basis of bulk electrolysis measurements. Highly reactive electrogenerated intermediates, such as Co(II) hydrides and ligand-reduced species, negatively affects the stability of the catalytic pathways they are involved in. This example is thus on the borderline between the benefits and detriments of using redox-active ligands. While the bipyridine motif enables the activation of otherwise absent productive catalytic pathways, it significantly limits the stability of the reaction intermediates involved. 2.5. Improving Stability. When it comes to redox-active ligands, stability gain is a general statement that can be found in a number of reports. If prevention of the formation of low-valent metal centers by distribution of the extra electron density all over the ligand is commonly reported, substantial evidence that it indeed positively affects the stability of the catalytic process is still lacking. In contrast, catalytic pathways involving the reduction of the ligand scaffold sometimes revealed themselves as a source of greater catalyst instability.3 Efforts should be made to extract metrics that provide insight regarding the actual effects of the ligand electronic involvement on the stability of catalytic systems. In this regard, Savéant and co-workers have formulated a useful descriptor that supplies valuable information about the lifetime of an operating catalyst in the diffusion-reaction layer.76 the catalytic mechanism followed by H2-evolving catalysts I.9 and I.10 (Figure 5).31 Ultimately, the use of redox-active ligands may enable catalytic pathways that completely shift the usual paradigm: the main site for the catalytic event is no longer the metal center but the ligand platform. Though examples of ligand-based electroassisted catalysis are still relatively limited,69−74 they have recently been exhaustively reviewed by Zhang and co-workers.75 2.4.1. Example 4: Redox-Active Ligand to Enable New Catalytic Pathways for H2 Evolution. In a recent study, Artero, Queyriaux, and co-workers have described the activity toward electroassisted H2 evolution of a cobalt(II) complex combining pendant bases and a redox-active moiety within a single tetrapyridyl ligand (complex I.11, Figure 5).3 In DMF, this complex features two successive monoelectronic reductions: a reversible metal-centered processassociated with the Co(II)/ Co(I) couplefollowed by an irreversible ligand-centered (L/ L•−) process. Using proton sources of variable strength, the authors evidenced the development of a range of catalytic responses (Figure 6). Thus, strong acids enable protonation of 3. DELETERIOUS EFFECTS OF REDOX-ACTIVE LIGANDS ON THE ELECTROCATALYTIC BEHAVIOR Different unexpected side effects related to the involvement of redox-active moieties throughout the electroassisted catalytic cycle have been identified in the literature. In the following paragraphs, we have grouped those different processes depending on their mode of operation. 3.1. Ligand-Centered Chemical Reactivity. Uptake of an electron within molecular orbitals displaying a strong ligand character may open up undesired reactivities of the reduced catalyst. The electrogenerated species can generally be described as radical anions and are indeed potent nucleophiles. Rather than simple sequestration of this additional electron density, a number of ligands have been shown to react with electrophilic substrates such as protons and carbon dioxide. As a main effect, the electron within the ligand platform will be trapped through the formation ofusually irreversiblechemical bonds: C−C (carboxylation), C−O (carbonation), or C−H (dearomatization) bonds. Now engaged in a covalent bond, this electron can no longer participate in the catalytic process. Further reductions are thus needed for catalysis to occur. Consequently, the overpotential requirement associated with the catalytic process may be increased. In many cases, these types of reactions remain “invisible” on a macroscopic scale, as long as the catalytic system displays satisfactory performance. Figure 6. Proposed mechanistic pathways followed by complex I.11 during electroassisted H2 evolution in the presence of acids of various strengths in DMF. The bipyridine redox-active motif is notably involved in the presence of weak acids (Et3NH+ − green path−and CH3COOH − blue path). Reprinted with permission from ref 3. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society. the electrogenerated cobalt(I) center, resulting in the formation of catalytically competent Co(III) hydrides. Kinetically reluctant, this compound may be further reduced to promote faster H2 evolution. Weaker acids are unable to trigger metal protonation upon one-electron reduction. The redox activity of the ligand scaffold proves crucial in initiating a catalytic sequence of events (EECC when acetic acid is used or ECEC in the case of HNEt3+). Interestingly, the relative stabilities of these different catalytic pathways have been quantitatively 4028 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00237 ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4024−4035 ACS Catalysis pubs.acs.org/acscatalysis Perspective Figure 7. Structures of some complexes displaying redox-active ligands that have been shown to undergo processes detrimental to an electroassisted catalytic reaction. Figure 8. Example of catalyst decomposition proposed by McCrory and co-workers. Adapted with permission from ref 6. Copyright 2018 Royal Society of Chemistry. Similarly, carboxylation of imino carbon centers was proposed as a deactivation pathway in a number of reports using redoxactive ligands (complex II.5, Figure 8).6,79 Electrochemical carboxylation reactions have been exploited as early as 1981 to achieve electrosynthesis of N-carboxylated heteroaromatic compounds.80 Since then, many examples have been reported, some of them involving structures usually employed as ligands in electroassisted catalysis.81 3.1.2. Example 6: Electrochemical Deactivation Processes in Proton-Responsive Functionalized Redox Ligands. The incorporation of acidic or basic moieties near the metal center of CO2 reduction or H2 evolution catalysts is a well-established strategy. It has opened the way to the development of highperformance catalysts by increasing the local proton concentration,18 providing proton relays3,57,82 or stabilizing catalytic adducts.83−85 In most cases, these functional groups assisting the catalytic process were attached on electrochemically innocent ligands. However, Fujita and co-workers have shown that the combination of a redox-active moiety and proton-responsive groups within the same ligand resulted in new deactivation pathways through the formation of catalytically unproductive species.35 In an attempt to foster catalytic processes leading to CO2-to-CO conversion in the well-described [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(S)]2+ system (tpy = 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine, bpy = 2,2′bipyridine, and S = a neutral solvent molecule), the authors introduced hydroxyl groups in the 6,6′-positions of the bipyridine ligand (complex II.2, Figure 7). This design was intended to stabilize a metal−CO2 adduct via hydrogen bonding or to facilitate the protonation of this metallocarboxylate intermediatea key step toward the release of CO. Controlled-potential electrolysis (CPE) experiments were performed on a mercury-pool electrode to assess the ability of this complex to assist the reduction of CO2 in acetonitrile. Faradaic yields as low as 4.1% for CO and 5.9% for formate were observed, suggesting the existence of processes undermining the catalysis. A combination of experimental techniques and DFT calculations was used to shed light on the deactivation pathway However, these interfering reactivities sometimes have a deeper effect. In some situations, they have been found to impedeor even preventfurther catalytic processes by modification of the structural integrity of the ligand. Even if they do not result in an immediate demetalation, ligand modifications can still have damaging consequences on the catalysis. Changes in the accessibility of the metal center, the overall charge of the complex, or the electronic balance within the catalystthis list is not exhaustiveare thus prone to occur and to significantly hamper the desired reactivity, resulting in low Faradaic yield. These extreme situations sometimes allow pointing out the adverse effects of certain redox-active ligands. 3.1.1. Example 5: Electrochemically Induced Carboxylation of Polypyridyl-Based Transition-Metal Catalysts. Among the wide diversity of molecular complexes developed to achieve H2 evolution and CO2 reduction, polypyridyl-based transitionmetal complexes have played a major role.77,78 Of particular interest to the scope of this Perspective is the study of the electrocatalytic behavior of [M(tpy)2]2+ (M = Co, Ni, Zn) complexes toward CO2 reduction in organic medium. In 2014, Elgrishi et al. demonstrated that nickel(II) and cobalt(II) bisterpyridine complexes are capable of electroassisted CO2-to-CO conversion, the catalytic cycle being initiated by ligand-based reductions and loss of a terpyridine ligand.34 Although selective, the cobalt(II) catalyst (complex II.1, Figure 7) suffers from modest Faradaic yields (about 20%, under optimized conditions), which limits its scope. In order to better understand the origin of this electron wastage, the authors sought to highlight the existence of deleterious side processes or catalytic dead ends. To this end, the behavior of the Zn(II) complex, a diamagnetic analogue of the catalysts, was investigated under electrocatalytic and photocatalytic conditions. Chemical trapping by iodomethane and 1H NMR experiments were performed and strongly suggested deactivation reactions involving the terpyridine ligand, namely loss of aromaticity of the pyridine rings and carboxylation. 4029 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00237 ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4024−4035 ACS Catalysis pubs.acs.org/acscatalysis and the species involved. Collectively, these data suggest a first step of reductive deprotonation to produce a doubly deprotonated complex. Carbon dioxide was shown to efficiently react with the now-deprotonated ligand to form carbonates (Figure 9). Such an electroassisted reaction of carbon dioxide Perspective proton uptake over the catalytic cyclesusing electroresponsive proton relaystheir role can also be potentially detrimental. In a recent study, Hess and co-workers investigated the electrocatalytic behavior of [Co(Mabiq)(THF)]+, a cobalt(II) complex displaying a macrocyclic biquinazoline ligand (complex II.3, Figure 7).36 This complex exhibits the particular feature of successively undergoing two reversible monoelectronic reductions centered on its largely conjugated ligand, leaving the metal center virtually unchanged. Upon addition of p-cyanoanilinium, this complex is capable of electroassisting the reduction of protons in acetonitrile. However, unlike many other molecular electrocatalysts such as cobaloximes,88−90 the authors noticed that the development of the electrocatalytic wave proceeds at a potential lower than that associated with the formation of the formal CoI species. This behavior prompted them to use an electrochemical technique that is only rarely employed in electrocatalysis to explore the early steps of the catalytic pathway. By combining the results of rotating ring-disk electrode (RRDE) experiments and online electrochemical mass spectrometry (OLEMS) measurements, the authors were able to evidence a nonproductive precatalytic event. In the presence of acid, the complex thus undergoes a bielectronic reduction that is coupled with at least one protonation. This results in the initial storage of a hydride equivalent (2 e− and 1 H+) within the ligand platform. Although the authors could not establish the exact nature of the resulting species, they clearly showed its inability to drive catalysis. A new, more energetic electron is finally required to complete the catalytic cycle, resulting in an increased overpotential. Similar results were obtained by Savéant and co-workers when they investigated the ability of a Cu(II) tetraphenylporphyrin (TPP) complex to drive H2 evolution in DMF.47 When triethylammonium was used as a proton source, the once monoelectronic wave becomes more complex, displaying a 3 e− 3 H+ coupled process that has been assigned to hydrogenation of the ring. In this case, however, no catalysis could be achieved. 3.2. Metal-Centered Chemical Trapping. Catalytic cycles are expected to be derived from a reactive intermediate formed upon an inner-sphere reaction between the electrogenerated active form of the catalyst and its substrate (here, CO2 or H+). The introduction of redox-active ligands is likely to affect this classical scheme by disrupting the electronic balance within the catalytic system. The reduction of the ligand framework produces a priori two main effects. First, the nucleophilicity of the metal center is only slightly increased in comparison to what it is in the absence of a redox-active ligand, i.e. metal-centered reduction. Although some recent works have shed light on effective ligand-centered electrocatalytic processes (vide supra), it is important to remember that the vast majority of the catalytic pathways resolved so far strongly rely on the metal center, the electrochemically controlled nucleophilicity of which being the main trigger enabling the formation of a primary catalyst− substrate adduct, as a gateway to the catalytic cycle. A decreased Lewis basicity of the metal center thus potentially hampers the reactivity by limiting its interaction with electrophilic substrates. Even if this reactivity is not completely inhibited, the resulting adducts may display weakly activated substrates playing a kinetic trap role. Second, the electron density acquired by the ligand framework is sometimes the origin of interfering side reactions capable of obstructing access to one of the catalyst coordination sites. Such phenomena are likely deleterious to catalytic turnover. Figure 9. Catalytic and deactivation pathways proposed to occur over the course of the electroassisted reduction of CO2 by complex II.2. with alcohols has been previously reported as an electrosynthetic tool toward the preparation of organic carbonates.86 Interestingly, the modification of the ligand framework does not hamper the ability of the metal center to assist the CO2-to-CO conversion but seems to inhibit further CO release. The resulting bis-carbonated carbonyl species have indeed been identified from the precipitate that formed upon CPE experiments. With a parallel interest, Chardon-Noblat and co-workers have studied the electro- and photocatalytic performances of a manganese(I) tricarbonyl complex displaying [1,10]-phenanthroline-5,6-dione as a ligand.87 Upon two successive ligandbased reductions under a CO2 atmosphere, a bis-carbonated adduct was identified. Here, the catalytic process remains effective and bulk electrolysis experiments performed in acetonitrile containing 5% water resulted in efficient CO2-toCO conversion (100% Faradaic yield). 3.1.3. Example 7: Hydride Sink Effect in a Cobalt(II) Complex Bearing a Macrocyclic Biquinazoline Ligand. The harmful changes that occur at the redox-active ligands are not restricted to unwanted reactions with CO2 in the context of its electroassisted reduction. Protonation processes have also been shown to occur when hydrogen production was pursued. Although these reactions are sometimes desired to facilitate the 4030 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00237 ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4024−4035 ACS Catalysis pubs.acs.org/acscatalysis 3.2.1. Example 8: Limited Reactivity of the Catalyst Due to a Decreased Nucleophilicity of the Metal Center. Limiting the increase in nucleophilicity of the metal centerthrough sequestration of a significant part of the electron density in ligand-centered orbitalshas recently been shown to affect catalytic properties. Queyriaux, Hammarström, and co-workers thus reported the electrocatalytic investigation of a polypyridylbased cobalt(II) complex toward CO2 reduction.38 Displaying a redox-active moiety and basic sites in close proximity to the metal center, this complex was previously shown to be an efficient catalyst for the reduction of protons in aqueous and organic media (complex I.11, Figure 5).91 On the basis of a comparison with a Zn(II) analogue and DFT calculations, the location of the two first reductions was unambiguously established: the first being metal-centered and the second mainly involving the ligand scaffold. Although voltammograms displayed significant current enhancement in CO2-saturated DMF solutions, CPE experiments revealed a rather inefficient catalytic process suffering from both low selectivity and low Faradaic yields (FYCO = 7.4% and FYHCOOH = 7.9%). In order to gain some insight into the nature of the processes undermining CO2 reduction catalysis, chemical reductions were coupled to UV−vis and IR spectroscopy and DFT calculations. These different techniques revealed the formation of an adduct between the cobalt catalyst and a CO2 molecule, via the twoelectron-reduced complex. In addition, the formation of a significant amount of CO trapped complexes was excluded. The electronic nature of the CO2 adduct was investigated by DFT calculations, which helped to establish that coordination of CO2 to the metal center does not result in a significant charge redistribution within the newly bound CO2 ligand-centered orbitals. In many systems, such an electronic reorganization has been proposed to be a crucial step of the CO2 reduction, usually resulting in a metallocarboxylate complex. The resulting metalboundbut poorly activatedCO2 molecule was expected to hardly react with oxide acceptors (such as carbon dioxide or protons) as required to close the catalytic cycle. The authors suggested that this weak activation was caused by an effective electron trapping within the ligand. In a related study, Musgrave, Luca, and co-workers have explored the CO2 reduction electroassisted by bis-NHC pincer complexes of the type M(CO)3CNCBn (M = Re, Mn).37 While the Mn derivative displays promising ability to reduce CO2 on the voltammetric scale, the Re complex proves to be mostly inactive. Electronic structures of the one-electron-reduced catalysts were computed and provided insightful information on the role played by the ligand scaffold. A spin population density analysis revealed significantly different partitioning of the electron density between ligand-centered and metal-based orbitals, depending on the metal center. Whereas 66% of the spin density resides on the metal in the manganese complex, only 38% of it is located on the rhenium. This dramatic modification of the metalloradical character of the catalytic intermediates was proposed to be the key feature dictating the ability of the pincer complexes to driveor notthe catalytic process. 3.2.2. Example 9: Prevention of the Metal Center Accessibility by Metallacycle Formation. Reactions of the reduced ligand with reactants or reduction products are potentially generating new species that display trapped coordination sites. In 2015, Kubiak, Peters, and co-workers investigated the electrocatalytic behavior of mononuclear molybdenum complexes of the type [Mo(CO)4(PMI)] (PMI Perspective = pyridine monoimine), which exhibit two successive redox processes centered on the pyridine monoketimine ligand (complex II.4, Figure 7).92 Although they displayed encouraging current enhancement when the CVs were recorded under CO2 saturation, the complexes were revealed to be rather ineffective catalysts under continuous operation. Faradaic yields toward CO formation were limited to 10% as a maximum. In order to better understand the processes underpinning the deactivation, chemical reductions, IR spectroelectrochemical methods, and NMR investigations were used. These techniques pointed out the formation of an unusual CO2 adduct in which the CO2 carbon atom binds to the imine carbon atom of the reduced complex (Figure 10). In addition to provide strong Figure 10. (a) Metal−ligand cooperative capture of CO2 by complex II.4 over the course of the electroassisted reduction of CO2 and (b) metallacycle ring closing upon reduction of complex II.5. evidence of the C−C bond formation between the reduced ligand and a CO2 molecule, the crystal structure of this intermediate revealed that the metal center is bound to an oxygen atom of the newly formed carboxylate. By restriction of access to one of the coordination sites of the molybdenum center, the formation of this adduct is likely to be detrimental to the electrocatalytic activity. In a related study, Vogt and coworkers have evidenced a similar reversible process on a rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complex.93 CO-trapped intermediates have recently been shown to efficiently act as catalytic dead ends by preventing coordination site liberation.94−97 The potentially negative effect of these types of intermediates could, however, be amplified by the presence of functionalized redox-active ligands. As such, works by Tanaka and co-workers may provide interesting insights.98 Indeed, in 2005, the authors reported the unusual electrochemical behavior of a ruthenium carbonyl complex bearing a redox-active ligand (complex II.5, Figure 10). Once it is reduced, this bipyridine ligandfeaturing a quinone-like motifis capable of attacking the carbon atom of the carbonyl ligand thanks to the increased nucleophilicity of its pyridonato group. The resulting stable fivemembered metallacycle prevents reductive cleavage of the CO ligand and thus inhibits any future reactivity at the metal center. Although the behavior of this complex with respect to electroassisted CO2 reduction has not been investigated so far, this type of reactivity appears to be relatively common.99−101 As far as redox-active ligands are considered, such metallacycle 4031 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00237 ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4024−4035 ACS Catalysis pubs.acs.org/acscatalysis formation could play a major role in a number of catalytic systems. ■ 4. CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOK Redox-active ligands are growing in importance among the various strategies elaborated to design selective, efficient, and stable catalysts for electroassisted catalytic reductions of CO2 and H+. For most systems, however, a quantitative analysis of their exact roles on the catalyst behavior is still lacking. As a consequence, no obvious relationship between catalyst metrics improvement and the redox-active nature of a ligand can be drawn. This observationpreviously made by Savéant102is probably due to the variety of ways those motifs act. Nevertheless, some specific observations can be made to facilitate further development of complexes using redox-active moiety for electroassisted catalysis: (1) Depending on whether you want to reduce CO2 or protons, the expected effects such motifs may have are quite different. The nucleophilicity of the metal center all along the catalytic cycleshould be considered as a key element. Where typically high Lewis basicity of the metal center is sought in the case of H2-evolving catalysts to promote hydrides generation, this feature has to be significantly more balanced when it comes to CO2 reduction to ensure selectivity. In this specific case, redox-active ligands thus appear to be useful tools to tune the electronics of the metal center by allocating part of the electroacquired electron density to the ligand scaffold. In the case of proton reduction, the main concern is typically to lower the overpotential requirement of the catalytic system, which often comes at the expense of the catalytic rate. (2) Although this is not a rule that can be generalized to all systems, it seems that redox-active ligands capable of delocalizing the excess electron density over largely conjugated systems are less prone to side reactions. Localization of the radical within a restricted part of the ligand scaffold commonly leads to irreversible and unproductive bond formation with the electrophilic substrates. (3) Whenever possible, a comparison with complexes bearing redox-innocent ligands should be systematically carried out. However, caution should be taken to ensure the relevance of such benchmarking. If certain molecular parameters (such as the rigidity of the ligand or the geometry adopted by the complex, as examples) differ too significantly between the two species, it may be tricky to provide meaningful interpretations on the effects of introducing redox-active ligands on the catalytic process. Quantitative assessments of the effects of introducing redox-active ligands on specific electrochemical events (ligand exchange rate constants, stability descriptors, ...) have recently been highlighted. Efforts on this front must be pursued in order to comprehensively shed light on the key parameters at stake when redox-active ligands are involved. (4) The identification of postelectrolysis solution contents is crucial to evidence catalyst evolution under the working conditions. When this is coupled to in situ probing techniques and DFT calculations, it may help to more clearly decipher catalytic dead ends and real active forms of the catalysts. This knowledge is essential for a better Perspective understanding of the redox-active ligand role and may inspire new efficient, selective, and stable systems. AUTHOR INFORMATION Corresponding Author Nicolas Queyriaux − CNRS, LCC (Laboratoire de Chimie de Coordination), 31077 Toulouse, France; orcid.org/00000002-8525-280X; Email: nicolas.queyriaux@lcc-toulouse.fr Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00237 Notes The author declares no competing financial interest. ■ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS N.Q. expresses his gratitude to Dr. V. Artero, Dr. M. ChavarotKerlidou, Dr. N. Kaeffer, and Dr. C. Esmieu for fruitful discussions regarding this Perspective. ■ REFERENCES (1) Cometto, C.; Chen, L.; Lo, P.-K.; Guo, Z.; Lau, K.-C.; Anxolabéhère-Mallart, E.; Fave, C.; Lau, T.-C.; Robert, M. Highly Selective Molecular Catalysts for the CO2-to-CO Electrochemical Conversion at Very Low Overpotential. Contrasting Fe vs Co Quaterpyridine Complexes upon Mechanistic Studies. ACS Catal. 2018, 8 (4), 3411−3417. (2) Cometto, C.; Chen, L.; Anxolabéhère-Mallart, E.; Fave, C.; Lau, T.-C.; Robert, M. Molecular Electrochemical Catalysis of the CO2-toCO Conversion with a Co Complex: A Cyclic Voltammetry Mechanistic Investigation. Organometallics 2019, 38 (6), 1280−1285. (3) Queyriaux, N.; Sun, D.; Fize, J.; Pécaut, J.; Field, M. J.; ChavarotKerlidou, M.; Artero, V. Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution with a Cobalt Complex Bearing Pendant Proton Relays: Acid Strength and Applied Potential Govern Mechanism and Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (1), 274−282. (4) Nippe, M.; Khnayzer, R. S.; Panetier, J. A.; Zee, D. Z.; Olaiya, B. S.; Head-Gordon, M.; Chang, C. J.; Castellano, F. N.; Long, J. R. Catalytic proton reduction with transition metal complexes of the redox-active ligand bpy2PYMe. Chemical Science 2013, 4 (10), 3934−3945. (5) Lacy, D. C.; McCrory, C. C. L.; Peters, J. C. Studies of CobaltMediated Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction Using a Redox-Active Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53 (10), 4980−4988. (6) Nie, W.; McCrory, C. C. L. Electrocatalytic CO2 reduction by a cobalt bis(pyridylmonoimine) complex: effect of acid concentration on catalyst activity and stability. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54 (13), 1579− 1582. (7) Liu, F.-W.; Bi, J.; Sun, Y.; Luo, S.; Kang, P. Cobalt Complex with Redox-Active Imino Bipyridyl Ligand for Electrocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide to Formate. ChemSusChem 2018, 11 (10), 1656− 1663. (8) Vennampalli, M.; Liang, G.; Katta, L.; Webster, C. E.; Zhao, X. Electronic Effects on a Mononuclear Co Complex with a Pentadentate Ligand for Catalytic H2 Evolution. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53 (19), 10094− 10100. (9) Wang, P.; Liang, G.; Reddy, M. R.; Long, M.; Driskill, K.; Lyons, C.; Donnadieu, B.; Bollinger, J. C.; Webster, C. E.; Zhao, X. Electronic and Steric Tuning of Catalytic H2 Evolution by Cobalt Complexes with Pentadentate Polypyridyl-Amine Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (29), 9219−9229. (10) Jurss, J. W.; Khnayzer, R. S.; Panetier, J. A.; El Roz, K. A.; Nichols, E. M.; Head-Gordon, M.; Long, J. R.; Castellano, F. N.; Chang, C. J. Bioinspired design of redox-active ligands for multielectron catalysis: effects of positioning pyrazine reservoirs on cobalt for electro- and photocatalytic generation of hydrogen from water. Chemical Science 2015, 6 (8), 4954−4972. 4032 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00237 ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4024−4035 ACS Catalysis pubs.acs.org/acscatalysis (11) Chen, L.; Khadivi, A.; Singh, M.; Jurss, J. W. Synthesis of a pentadentate, polypyrazine ligand and its application in cobaltcatalyzed hydrogen production. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2017, 4 (10), 1649−1653. (12) Boutin, E.; Wang, M.; Lin, J. C.; Mesnage, M.; Mendoza, D.; Lassalle-Kaiser, B.; Hahn, C.; Jaramillo, T. F.; Robert, M. Aqueous Electrochemical Reduction of Carbon Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide into Methanol with Cobalt Phthalocyanine. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (45), 16172−16176. (13) Wang, M.; Torbensen, K.; Salvatore, D.; Ren, S.; Joulié, D.; Dumoulin, F.; Mendoza, D.; Lassalle-Kaiser, B.; Işci, U.; Berlinguette, C. P.; Robert, M. CO2 electrochemical catalytic reduction with a highly active cobalt phthalocyanine. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 3602. (14) Xia, Y.; Kashtanov, S.; Yu, P.; Chang, L.-Y.; Feng, K.; Zhong, J.; Guo, J.; Sun, X. Identification of dual-active sites in cobalt phthalocyanine for electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction. Nano Energy 2020, 67, 104163. (15) De Riccardis, A.; Lee, M.; Kazantsev, R. V.; Garza, A. J.; Zeng, G.; Larson, D. M.; Clark, E. L.; Lobaccaro, P.; Burroughs, P. W. W.; Bloise, E.; Ager, J. W.; Bell, A. T.; Head-Gordon, M.; Mele, G.; Toma, F. M. Heterogenized Pyridine-Substituted Cobalt(II) Phthalocyanine Yields Reduction of CO2 by Tuning the Electron Affinity of the Co Center. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12 (5), 5251−5258. (16) Mahammed, A.; Mondal, B.; Rana, A.; Dey, A.; Gross, Z. The cobalt corrole catalyzed hydrogen evolution reaction: surprising electronic effects and characterization of key reaction intermediates. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50 (21), 2725−2727. (17) Sinha, W.; Mahammed, A.; Fridman, N.; Diskin-Posner, Y.; Shimon, L. J. W.; Gross, Z. Superstructured metallocorroles for electrochemical CO2 reduction. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55 (79), 11912−11915. (18) Costentin, C.; Drouet, S.; Robert, M.; Savéant, J.-M. A Local Proton Source Enhances CO2 Electroreduction to CO by a Molecular Fe Catalyst. Science 2012, 338 (6103), 90−94. (19) Costentin, C.; Robert, M.; Savéant, J.-M.; Tatin, A. Efficient and selective molecular catalyst for the CO2-to-CO electrochemical conversion in water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112 (22), 6882. (20) Costentin, C.; Passard, G.; Robert, M.; Savéant, J.-M. Ultraefficient homogeneous catalyst for the CO2-to-CO electrochemical conversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111 (42), 14990. (21) Roy, S.; Miller, M.; Warnan, J.; Leung, J. J.; Sahm, C. D.; Reisner, E. Electrocatalytic and Solar-Driven Reduction of Aqueous CO2 with Molecular Cobalt Phthalocyanine−Metal Oxide Hybrid Materials. ACS Catal. 2021, 11 (3), 1868−1876. (22) Abe, T.; Yoshida, T.; Tokita, S.; Taguchi, F.; Imaya, H.; Kaneko, M. Factors affecting selective electrocatalytic co2 reduction with cobalt phthalocyanine incorporated in a polyvinylpyridine membrane coated on a graphite electrode. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1996, 412 (1), 125−132. (23) Zhu, M.; Ye, R.; Jin, K.; Lazouski, N.; Manthiram, K. Elucidating the Reactivity and Mechanism of CO2 Electroreduction at Highly Dispersed Cobalt Phthalocyanine. ACS Energy Letters 2018, 3 (6), 1381−1386. (24) Römelt, C.; Ye, S.; Bill, E.; Weyhermüller, T.; van Gastel, M.; Neese, F. Electronic Structure and Spin Multiplicity of Iron Tetraphenylporphyrins in Their Reduced States as Determined by a Combination of Resonance Raman Spectroscopy and Quantum Chemistry. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57 (4), 2141−2148. (25) Boutin, E.; Merakeb, L.; Ma, B.; Boudy, B.; Wang, M.; Bonin, J.; Anxolabéhère-Mallart, E.; Robert, M. Molecular catalysis of CO2 reduction: recent advances and perspectives in electrochemical and light-driven processes with selected Fe, Ni and Co aza macrocyclic and polypyridine complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49 (16), 5772−5809. (26) Anxolabéhère, E.; Chottard, G.; Lexa, D. Highly reduced iron porphyrins: UV-vis and resonance Raman spectro-electrochemical studies of FeTPP and FeTF5PP. New J. Chem. 1994, 18, 889−899. (27) Derrick, J. S.; Loipersberger, M.; Chatterjee, R.; Iovan, D. A.; Smith, P. T.; Chakarawet, K.; Yano, J.; Long, J. R.; Head-Gordon, M.; Chang, C. J. Metal−Ligand Cooperativity via Exchange Coupling Perspective Promotes Iron- Catalyzed Electrochemical CO2 Reduction at Low Overpotentials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (48), 20489−20501. (28) Su, X.; McCardle, K. M.; Panetier, J. A.; Jurss, J. W. Electrocatalytic CO2 reduction with nickel complexes supported by tunable bipyridyl-N-heterocyclic carbene donors: understanding redoxactive macrocycles. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54 (27), 3351−3354. (29) Su, X.; McCardle, K. M.; Chen, L.; Panetier, J. A.; Jurss, J. W. Robust and Selective Cobalt Catalysts Bearing Redox-Active BipyridylN-heterocyclic Carbene Frameworks for Electrochemical CO2 Reduction in Aqueous Solutions. ACS Catal. 2019, 9 (8), 7398−7408. (30) Gonell, S.; Massey, M. D.; Moseley, I. P.; Schauer, C. K.; Muckerman, J. T.; Miller, A. J. M. The Trans Effect in Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction: Mechanistic Studies of Asymmetric Ruthenium Pyridyl-Carbene Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (16), 6658− 6671. (31) Kohler, L.; Niklas, J.; Johnson, R. C.; Zeller, M.; Poluektov, O. G.; Mulfort, K. L. Molecular Cobalt Catalysts for H2 Generation with Redox Activity and Proton Relays in the Second Coordination Sphere. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58 (2), 1697−1709. (32) Zarkadoulas, A.; Field, M. J.; Artero, V.; Mitsopoulou, C. A. Proton-Reduction Reaction Catalyzed by Homoleptic Nickel−bis-1,2dithiolate Complexes: Experimental and Theoretical Mechanistic Investigations. ChemCatChem 2017, 9 (12), 2308−2317. (33) Straistari, T.; Hardré, R.; Fize, J.; Shova, S.; Giorgi, M.; Réglier, M.; Artero, V.; Orio, M. Hydrogen Evolution Reactions Catalyzed by a Bis(thiosemicarbazone) Cobalt Complex: An Experimental and Theoretical Study. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24 (35), 8779−8786. (34) Elgrishi, N.; Chambers, M. B.; Artero, V.; Fontecave, M. Terpyridine complexes of first row transition metals and electrochemical reduction of CO2 to CO. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16 (27), 13635−13644. (35) Duan, L.; Manbeck, G. F.; Kowalczyk, M.; Szalda, D. J.; Muckerman, J. T.; Himeda, Y.; Fujita, E. Noninnocent ProtonResponsive Ligand Facilitates Reductive Deprotonation and Hinders CO2 Reduction Catalysis in [Ru(tpy)(6DHBP)(NCCH3)]2+ (6DHBP = 6,6′-(OH)2bpy). Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55 (9), 4582−4594. (36) Tok, G. C.; Freiberg, A. T. S.; Gasteiger, H. A.; Hess, C. R. Electrocatalytic H2 Evolution by the Co-Mabiq Complex Requires Tempering of the Redox-Active Ligand. ChemCatChem 2019, 11 (16), 3973−3981. (37) Myren, T. H. T.; Alherz, A.; Stinson, T. A.; Huntzinger, C. G.; Lama, B.; Musgrave, C. B.; Luca, O. R. Metalloradical intermediates in electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO: Mn versus Re bis-Nheterocyclic carbene pincers. Dalton Transactions 2020, 49 (7), 2053− 2057. (38) Queyriaux, N.; Abel, K.; Fize, J.; Pécaut, J.; Orio, M.; Hammarström, L. From non-innocent to guilty: on the role of redoxactive ligands in the electro-assisted reduction of CO2 mediated by a cobalt(ii)-polypyridyl complex. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2020, 4 (7), 3668−3676. (39) Appel, A. M.; Helm, M. L. Determining the Overpotential for a Molecular Electrocatalyst. ACS Catal. 2014, 4 (2), 630−633. (40) Fourmond, V.; Jacques, P.-A.; Fontecave, M.; Artero, V. H2 Evolution and Molecular Electrocatalysts: Determination of Overpotentials and Effect of Homoconjugation. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49 (22), 10338−10347. (41) Fujita, E. Photochemical carbon dioxide reduction with metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999, 185−186, 373−384. (42) Zhu, D. D.; Liu, J. L.; Qiao, S. Z. Recent Advances in Inorganic Heterogeneous Electrocatalysts for Reduction of Carbon Dioxide. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28 (18), 3423−3452. (43) Chen, L.; Guo, Z.; Wei, X.-G.; Gallenkamp, C.; Bonin, J.; Anxolabéhère-Mallart, E.; Lau, K.-C.; Lau, T.-C.; Robert, M. Molecular Catalysis of the Electrochemical and Photochemical Reduction of CO2 with Earth-Abundant Metal Complexes. Selective Production of CO vs HCOOH by Switching of the Metal Center. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (34), 10918−10921. (44) Sheng, H.; Frei, H. Direct Observation by Rapid-Scan FT-IR Spectroscopy of Two-Electron-Reduced Intermediate of Tetraaza 4033 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00237 ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4024−4035 ACS Catalysis pubs.acs.org/acscatalysis Catalyst [CoIIN4H(MeCN)]2+ Converting CO2 to CO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (31), 9959−9967. (45) Elgrishi, N.; Chambers, M. B.; Fontecave, M. Turning it off! Disfavouring hydrogen evolution to enhance selectivity for CO production during homogeneous CO2 reduction by cobalt−terpyridine complexes. Chemical Science 2015, 6 (4), 2522−2531. (46) Costentin, C.; Savéant, J.-M. Multielectron, Multistep Molecular Catalysis of Electrochemical Reactions: Benchmarking of Homogeneous Catalysts. ChemElectroChem 2014, 1 (7), 1226−1236. (47) Bhugun, I.; Lexa, D.; Savéant, J.-M. Homogeneous Catalysis of Electrochemical Hydrogen Evolution by Iron(0) Porphyrins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118 (16), 3982−3983. (48) Elgrishi, N.; Kurtz, D. A.; Dempsey, J. L. Reaction Parameters Influencing Cobalt Hydride Formation Kinetics: Implications for Benchmarking H2-Evolution Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (1), 239−244. (49) Koelle, U.; Paul, S. Electrochemical reduction of protonated cyclopentadienylcobalt phosphine complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1986, 25 (16), 2689−2694. (50) White, T. A.; Maji, S.; Ott, S. Mechanistic insights into electrocatalytic CO2 reduction within [RuII(tpy)(NN)X]n+ architectures. Dalton Transactions 2014, 43 (40), 15028−15037. (51) Clark, M. L.; Cheung, P. L.; Lessio, M.; Carter, E. A.; Kubiak, C. P. Kinetic and Mechanistic Effects of Bipyridine (bpy) Substituent, Labile Ligand, and Brønsted Acid on Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction by Re(bpy) Complexes. ACS Catal. 2018, 8 (3), 2021−2029. (52) Gonell, S.; Lloret-Fillol, J.; Miller, A. J. M. An Iron PyridylCarbene Electrocatalyst for Low Overpotential CO2 Reduction to CO. ACS Catal. 2020, 11, 615−626. (53) Chen, Z.; Chen, C.; Weinberg, D. R.; Kang, P.; Concepcion, J. J.; Harrison, D. P.; Brookhart, M. S.; Meyer, T. J. Electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO by polypyridyl ruthenium complexes. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47 (47), 12607−12609. (54) Kang, P.; Chen, Z.; Nayak, A.; Zhang, S.; Meyer, T. J. Single catalyst electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 in water to H2+CO syngas mixtures with water oxidation to O2. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7 (12), 4007−4012. (55) Gonell, S.; Assaf, E. A.; Duffee, K. D.; Schauer, C. K.; Miller, A. J. M. Kinetics of the Trans Effect in Ruthenium Complexes Provide Insight into the Factors That Control Activity and Stability in CO2 Electroreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (19), 8980−8999. (56) Rakowski Dubois, M.; Dubois, D. L. Development of Molecular Electrocatalysts for CO2 Reduction and H2 Production/Oxidation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42 (12), 1974−1982. (57) DuBois, D. L.; Bullock, R. M. Molecular Electrocatalysts for the Oxidation of Hydrogen and the Production of Hydrogen − The Role of Pendant Amines as Proton Relays. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011 (7), 1017−1027. (58) Drosou, M.; Kamatsos, F.; Mitsopoulou, C. A. Recent advances in the mechanisms of the hydrogen evolution reaction by non-innocent sulfur-coordinating metal complexes. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020, 7 (1), 37−71. (59) Solis, B. H.; Hammes-Schiffer, S. Computational Study of Anomalous Reduction Potentials for Hydrogen Evolution Catalyzed by Cobalt Dithiolene Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (37), 15253−15256. (60) McNamara, W. R.; Han, Z.; Yin, C.-J.; Brennessel, W. W.; Holland, P. L.; Eisenberg, R. Cobalt-dithiolene complexes for the photocatalytic and electrocatalytic reduction of protons in aqueous solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109 (39), 15594−15599. (61) Koshiba, K.; Yamauchi, K.; Sakai, K. A Nickel Dithiolate Water Reduction Catalyst Providing Ligand-Based Proton-Coupled ElectronTransfer Pathways. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (15), 4247−4251. (62) Straistari, T.; Fize, J.; Shova, S.; Réglier, M.; Artero, V.; Orio, M. A Thiosemicarbazone−Nickel(II) Complex as Efficient Electrocatalyst for Hydrogen Evolution. ChemCatChem 2017, 9 (12), 2262−2268. (63) Papadakis, M.; Barrozo, A.; Straistari, T.; Queyriaux, N.; Putri, A.; Fize, J.; Giorgi, M.; Réglier, M.; Massin, J.; Hardré, R.; Orio, M. Ligandbased electronic effects on the electrocatalytic hydrogen production by Perspective thiosemicarbazone nickel complexes. Dalton Transactions 2020, 49 (16), 5064−5073. (64) Calvary, C. A.; Hietsoi, O.; Hofsommer, D. T.; Brun, H. C.; Costello, A. M.; Mashuta, M. S.; Spurgeon, J. M.; Buchanan, R. M.; Grapperhaus, C. A. Copper bis(thiosemicarbazone) Complexes with Pendent Polyamines: Effects of Proton Relays and Charged Moieties on Electrocatalytic HER. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 2021 (3), 267−275. (65) Eisenberg, R.; Gray, H. B. Noninnocence in Metal Complexes: A Dithiolene Dawn. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50 (20), 9741−9751. (66) Matson, B. D.; McLoughlin, E. A.; Armstrong, K. C.; Waymouth, R. M.; Sarangi, R. Effect of Redox Active Ligands on the Electrochemical Properties of Manganese Tricarbonyl Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58 (11), 7453−7465. (67) Smieja, J. M.; Sampson, M. D.; Grice, K. A.; Benson, E. E.; Froehlich, J. D.; Kubiak, C. P. Manganese as a Substitute for Rhenium in CO2 Reduction Catalysts: The Importance of Acids. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52 (5), 2484−2491. (68) Sampson, M. D.; Nguyen, A. D.; Grice, K. A.; Moore, C. E.; Rheingold, A. L.; Kubiak, C. P. Manganese Catalysts with Bulky Bipyridine Ligands for the Electrocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide: Eliminating Dimerization and Altering Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (14), 5460−5471. (69) Thompson, E. J.; Berben, L. A. Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Production by an Aluminum(III) Complex: Ligand-Based Proton and Electron Transfer. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (40), 11642−11646. (70) Sherbow, T. J.; Fettinger, J. C.; Berben, L. A. Control of Ligand pKa Values Tunes the Electrocatalytic Dihydrogen Evolution Mechanism in a Redox-Active Aluminum(III) Complex. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56 (15), 8651−8660. (71) Solis, B. H.; Maher, A. G.; Dogutan, D. K.; Nocera, D. G.; Hammes-Schiffer, S. Nickel phlorin intermediate formed by protoncoupled electron transfer in hydrogen evolution mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113 (3), 485−492. (72) Haddad, A. Z.; Kumar, D.; Ouch Sampson, K.; Matzner, A. M.; Mashuta, M. S.; Grapperhaus, C. A. Proposed Ligand-Centered Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution and Hydrogen Oxidation at a Noninnocent Mononuclear Metal−Thiolate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (29), 9238−9241. (73) Haddad, A. Z.; Garabato, B. D.; Kozlowski, P. M.; Buchanan, R. M.; Grapperhaus, C. A. Beyond Metal-Hydrides: Non-TransitionMetal and Metal-Free Ligand-Centered Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution and Hydrogen Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (25), 7844−7847. (74) Haddad, A. Z.; Cronin, S. P.; Mashuta, M. S.; Buchanan, R. M.; Grapperhaus, C. A. Metal-Assisted Ligand-Centered Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution upon Reduction of a Bis(thiosemicarbazonato)Cu(II) Complex. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56 (18), 11254−11265. (75) Luo, G.-G.; Zhang, H.-L.; Tao, Y.-W.; Wu, Q.-Y.; Tian, D.; Zhang, Q. Recent progress in ligand-centered homogeneous electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6 (2), 343−354. (76) Costentin, C.; Passard, G.; Savéant, J.-M. Benchmarking of Homogeneous Electrocatalysts: Overpotential, Turnover Frequency, Limiting Turnover Number. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (16), 5461− 5467. (77) Queyriaux, N.; Jane, R. T.; Massin, J.; Artero, V.; ChavarotKerlidou, M. Recent developments in hydrogen evolving molecular cobalt(II)−polypyridyl catalysts. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 304−305, 3− 19. (78) Elgrishi, N.; Chambers, M. B.; Wang, X.; Fontecave, M. Molecular polypyridine-based metal complexes as catalysts for the reduction of CO2. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46 (3), 761−796. (79) Andrez, J.; Guidal, V.; Scopelliti, R.; Pécaut, J.; Gambarelli, S.; Mazzanti, M. Ligand and Metal Based Multielectron Redox Chemistry of Cobalt Supported by Tetradentate Schiff Bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (25), 8628−8638. (80) Fuchs, P.; Hess, U.; Holst, H. H.; Lund, H. Electrochemical Carboxylation of Some Heteroaromatic Compounds. Acta Chem. Scand. 1981, 35b, 185−192. 4034 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00237 ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4024−4035 ACS Catalysis pubs.acs.org/acscatalysis (81) Rossi, L. Electrochemical Methodologies for the Carboxylation Reactions in Organic Synthesis. An Alternative Re-use of Carbon Dioxide. Current Green Chemistry 2015, 2 (1), 77−89. (82) Wilson, A. D.; Newell, R. H.; McNevin, M. J.; Muckerman, J. T.; Rakowski DuBois, M.; DuBois, D. L. Hydrogen Oxidation and Production Using Nickel-Based Molecular Catalysts with Positioned Proton Relays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128 (1), 358−366. (83) Chapovetsky, A.; Do, T. H.; Haiges, R.; Takase, M. K.; Marinescu, S. C. Proton-Assisted Reduction of CO2 by Cobalt Aminopyridine Macrocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (18), 5765− 5768. (84) Chapovetsky, A.; Welborn, M.; Luna, J. M.; Haiges, R.; Miller, T. F.; Marinescu, S. C. Pendant Hydrogen-Bond Donors in Cobalt Catalysts Independently Enhance CO2 Reduction. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4 (3), 397−404. (85) Fujita, E.; Creutz, C.; Sutin, N.; Brunschwig, B. S. Carbon dioxide activation by cobalt macrocycles: evidence of hydrogen bonding between bound CO2 and the macrocycle in solution. Inorg. Chem. 1993, 32 (12), 2657−2662. (86) Zhang, L.; Niu, D.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, G.; Luo, Y.; Lu, J. Electrochemical activation of CO2 in ionic liquid (BMIMBF4): synthesis of organic carbonates under mild conditions. Green Chem. 2008, 10 (2), 202−206. (87) Stanbury, M.; Compain, J.-D.; Trejo, M.; Smith, P.; Gouré, E.; Chardon-Noblat, S. Mn-carbonyl molecular catalysts containing a redox-active phenanthroline-5,6-dione for selective electro- and photoreduction of CO2 to CO or HCOOH. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 240, 288−299. (88) Dempsey, J. L.; Brunschwig, B. S.; Winkler, J. R.; Gray, H. B. Hydrogen Evolution Catalyzed by Cobaloximes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42 (12), 1995−2004. (89) Razavet, M.; Artero, V.; Fontecave, M. Proton Electroreduction Catalyzed by Cobaloximes: Functional Models for Hydrogenases. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44 (13), 4786−4795. (90) Hu, X.; Cossairt, B. M.; Brunschwig, B. S.; Lewis, N. S.; Peters, J. C. Electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution by cobalt difluoroboryldiglyoximate complexes. Chem. Commun. 2005, 37, 4723−4725. (91) Queyriaux, N.; Giannoudis, E.; Windle, C. D.; Roy, S.; Pécaut, J.; Coutsolelos, A. G.; Artero, V.; Chavarot-Kerlidou, M. A noble metalfree photocatalytic system based on a novel cobalt tetrapyridyl catalyst for hydrogen production in fully aqueous medium. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2018, 2 (3), 553−557. (92) Sieh, D.; Lacy, D. C.; Peters, J. C.; Kubiak, C. P. Reduction of CO2 by Pyridine Monoimine Molybdenum Carbonyl Complexes: Cooperative Metal−Ligand Binding of CO2. Chem. - Eur. J. 2015, 21 (23), 8497−8503. (93) Stichauer, R.; Helmers, A.; Bremer, J.; Rohdenburg, M.; Wark, A.; Lork, E.; Vogt, M. Rhenium(I) Triscarbonyl Complexes with Redox-Active Amino- and Iminopyridine Ligands: Metal−Ligand Cooperation as Trigger for the Reversible Binding of CO2 via a Dearmomatization/Rearomatization Reaction Sequence. Organometallics 2017, 36 (4), 839−848. (94) Shimoda, T.; Morishima, T.; Kodama, K.; Hirose, T.; Polyansky, D. E.; Manbeck, G. F.; Muckerman, J. T.; Fujita, E. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction by Trigonal-Bipyramidal Cobalt(II) Polypyridyl Complexes: The Nature of Cobalt(I) and Cobalt(0) Complexes upon Their Reactions with CO2, CO, or Proton. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57 (9), 5486−5498. (95) Fernández, S.; Franco, F.; Casadevall, C.; Martin-Diaconescu, V.; Luis, J. M.; Lloret-Fillol, J. A Unified Electro- and Photocatalytic CO2 to CO Reduction Mechanism with Aminopyridine Cobalt Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (1), 120−133. (96) Mouchfiq, A.; Todorova, T. K.; Dey, S.; Fontecave, M.; Mougel, V. A bioinspired molybdenum−copper molecular catalyst for CO2 electroreduction. Chemical Science 2020, 11 (21), 5503−5510. (97) Lieske, L. E.; Rheingold, A. L.; Machan, C. W. Electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide with a molecular polypyridyl nickel complex. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2018, 2 (6), 1269−1277. Perspective (98) Tomon, T.; Koizumi, T.-a.; Tanaka, K. Stabilization and Destabilization of the Ru−CO Bond During the 2,2′-Bipyridin-6onato (bpyO)-Localized Redox Reaction of [Ru(terpy)(bpyO)(CO)](PF6). Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 2005 (2), 285−293. (99) Oyama, D.; Ukawa, N.; Hamada, T.; Takase, T. Reversible Intramolecular Cyclization in Ruthenium Complexes Induced by Ligand-centered One-electron Transfer on Bidentate Naphthyridine: An Important Intermediate for Both Metal− and Organo−Hydride Species. Chem. Lett. 2015, 44 (4), 533−535. (100) Nakajima, H.; Tanaka, K. Novel Reversible Metallacyclization in [Ru(bpy)2(η1-napy)(CO)]2+ (bpy = 2,2-bipyridine, napy = 1,8naphthyridine) by Intramolecular Attack of Non-Bonded Nitrogen of napy to Carbonyl Carbon. Chem. Lett. 1995, 24 (10), 891−892. (101) Tomon, T.; Koizumi, T.-a.; Tanaka, K. Electrochemical Hydrogenation of [Ru(bpy)2(napy-κN)(CO)]2+: Inhibition of Reductive Ru·CO Bond Cleavage by a Ruthenacycle. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44 (15), 2229−2232. (102) Costentin, C.; Savéant, J.-M.; Tard, C. Ligand “noninnocence” in coordination complexes vs. kinetic, mechanistic, and selectivity issues in electrochemical catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115 (37), 9104−9109. 4035 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00237 ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4024−4035