Major Depressive Disorder: Overview, Symptoms, & Treatment

advertisement

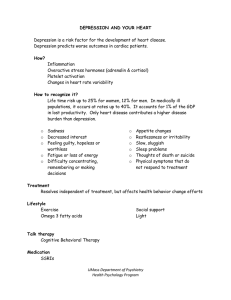

2/1/2021 View Monograph Diseases and Conditions: Major depressive disorder Major depressive disorder Overview Persistent sad, dysphoric mood with symptoms severe enough to interfere with an individual's ability to eat, enjoy life, sleep, study, or work Unipolar depressive disorder with onset in early adulthood and recurrences throughout life (at least two more episodes in 50% to 60% of patients) May occur in clusters or sporadically (typically with increasing frequency); may recur after symptom-free period Over half of patients do not recognize they are suffering from a treatable disease and do not seek treatment May be abbreviated as MDD Pathophysiology Exact underlying changes are not clearly defined; studies show an association with an alteration in serotonin activity in the central nervous system. Other neurotransmitters, including norepinephrine and dopamine, may be involved. Central nervous system disturbances in serotonin activity have been demonstrated in clinical and preclinical trials. The neurotransmitters norepinephrine, dopamine, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and glutamate have also been implicated. Changes occur in the receptor-neurotransmitter relationships in the limbic system. Changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal regulation system may be an adaptive deregulation of the stress response. Causes Exact cause unknown but appears to be multifactorial Genetic, familial, biochemical, physical, psychological, and social causes Pain and other physical causes that result in secondary depression Drugs such as beta-adrenergic blockers Seasonal depression Risk Factors Female gender Family history of major depression or bipolar disorder Chronic illness Chronic pain Substance abuse Adverse reaction to drugs such as beta-adrenergic blockers Stress and interpersonal loss Lack of social support Traumatic life events Incidence MDD affects about 20% of females and 12% of males at some point in their lifetime. It affects approximately 6.7% of the U.S. population over age 18. It can occur at any age, but the highest rate of occurrence is in people ages 25 to 44. https://lnareference.wkhpe.com/ref/view.do?key=c88daaabe66f43251bdc79295c4c606e73163d9c&nmn=openMonographFromGlobalId&monographId… 1/8 2/1/2021 View Monograph Complications Profound alteration in social, family, and occupational functioning Suicide Assessment History Profound loss of pleasure in all enjoyable activities for 1 month to 1 or more years Life problems or losses Physical disorder Somatic complaints, such as fatigue, malaise, and abdominal upset Loss of energy and motivation Use of prescription, nonprescription, or illicit drugs Change in eating habits (may result in weight gain or loss) Change in sleeping patterns Lack of interest in sex Constipation or diarrhea Irritability Difficulty concentrating Talk of suicide or suicide attempt Physical Findings Difficulty concentrating or thinking clearly Easily distracted Indecisiveness Delusions of persecution or guilt Agitation Psychomotor retardation Slow, monotone speech Flat affect Decline in grooming and hygiene Weight loss or gain DSM-5 Criteria According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), a diagnosis is confirmed when five or more of these symptoms occur (nearly every day) in the same 2-week period and represent a change from previous functioning, with at least one symptom being either a depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure: Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by either subjective account or observation by others Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day Significant weight loss or weight gain (greater than 5% of the patient's body weight in 1 month) when not dieting, or a change in appetite Insomnia or hypersomnia Psychomotor agitation or retardation Fatigue or loss of energy Feelings of worthlessness and excessive or inappropriate guilt Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness Recurrent thoughts of death; recurrent suicidal ideation with or without a specific plan; or suicide attempt (See Suicide prevention guidelines.) Symptoms not due to a mixed episode (mania, depression), a medical condition, the effects of a medication or other substance, or bereavement https://lnareference.wkhpe.com/ref/view.do?key=c88daaabe66f43251bdc79295c4c606e73163d9c&nmn=openMonographFromGlobalId&monographId… 2/8 2/1/2021 View Monograph Suicide prevention guidelines To help deter a potential suicide attempt in a patient with major depression, keep in mind these guidelines. ASSESS FOR CLUES TO SUICIDE Watch for such clues as communicating suicidal thoughts, threats, and messages; hoarding medication; talking about death and feelings of futility; giving away prized possessions; describing a suicide plan; and a change in behavior, especially as depression begins to lift. PROVIDE A SAFE ENVIRONMENT Check patient areas and correct dangerous conditions, such as exposed pipes, windows without safety glass, and access to the roof or open balconies. REMOVE DANGEROUS OBJECTS Remove from the patient's environment such objects as belts, razors, suspenders, light cords, glass, knives, nail files, and clippers. CONSULT WITH STAFF Recognize and document verbal and nonverbal suicidal behaviors. Keep the practitioner informed, and share data with all staff members. Assess the patient's risk, clarify the patient's specific restrictions, and plan for observation. Clarify day and night staff responsibilities and frequency of consultation. OBSERVE THE SUICIDAL PATIENT Place the patient on constant (one-on-one) supervision. Be alert when the patient is using a sharp object (as when shaving), taking medication, or in the bathroom (where the patient could potentially try to commit suicide). Assign the patient to a room near the nurses' station. Continuously observe the acutely suicidal patient. MAINTAIN PERSONAL CONTACT Help the suicidal patient feel supported, with resources available, and help the patient find hope. Encourage continuity of care and consistency of primary nurses. Building emotional ties is the ultimate technique for preventing suicide. Diagnostic Test Results Laboratory Toxicology screening suggests a drug-induced depression. Diagnostic Procedures Dexamethasone suppression test results may show a failure to suppress cortisol secretion. Other The Beck Depression Inventory, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, or another screening tool shows the onset, severity, duration, and progression of depressive symptoms. https://lnareference.wkhpe.com/ref/view.do?key=c88daaabe66f43251bdc79295c4c606e73163d9c&nmn=openMonographFromGlobalId&monographId… 3/8 2/1/2021 View Monograph Treatment General Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) Psychotherapy, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, interpersonal relationship therapy, supportive psychotherapy, group or family therapy, and psychodynamic psychotherapy Phototherapy (for seasonal affective disorder) Transcranial magnetic stimulation if unresponsive to one class of antidepressants Vagus nerve stimulation (for treatment-resistant depression) Hospitalization for suicidality Diet Well-balanced diet Dietary restriction of foods with tyramine if monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are prescribed (See Foods to avoid with MAOIs.) Foods to avoid with MAOIs A patient taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) needs to avoid foods rich in tyramine to prevent a possible hypertensive crisis. Such foods include the following: Aged cheeses Avocados Beer, wine (especially red wine), champagne Canned figs Caviar Fava beans Fermented, smoked, pickled, aged, or cured meats or fish Sauerkraut Sour cream Soy sauce Activity Scheduled activities of daily living Regular exercise program Medications Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as FLUoxetine hydrochloride, PARoxetine hydrochloride, sertraline hydrochloride, fluvoxaMINE maleate, citalopram hydrobromide, and escitalopram oxalate Selective serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as venlafaxine hydrochloride and DULoxetine hydrochloride Atypical antidepressants, such as buPROPion hydrobromide, nefazodone, mirtazapine, and trazodone hydrochloride Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), such as amitriptyline hydrochloride, nortriptyline hydrochloride, desipramine hydrochloride, clomiPRAMINE hydrochloride, doxepin hydrochloride, protriptyline, trimipramine maleate, and imipramine hydrochloride MAOIs, such as phenelzine sulfate and tranylcypromine sulfate St. John's wort ARIPiprazole for treatment-resistant depression https://lnareference.wkhpe.com/ref/view.do?key=c88daaabe66f43251bdc79295c4c606e73163d9c&nmn=openMonographFromGlobalId&monographId… 4/8 2/1/2021 View Monograph Nursing Considerations Nursing Interventions Encourage the patient to participate in psychotherapy, as indicated; reinforce the goals of therapy. Encourage the patient to express feelings. Allow time for the patient to talk; use therapeutic communication techniques to foster a trusting relationship. Listen attentively and respectfully; note and report any statements suggesting harm to self or others. Provide a structured routine. Encourage the patient to participate in activities and an exercise program; allow time for the patient to gradually increase the level of participation. Help the patient develop appropriate sleep hygiene measures to promote restful sleep. Encourage interaction with others; assist with initiating interactions on a small scale and gradually increasing them as the patient becomes comfortable. Document observations and significant conversations. Assume an active role in starting communication; begin slowly and simply to avoid overwhelming the patient. Plan activities for when the patient's energy levels are highest; encourage patient participation in self-care to foster self-esteem. Offer positive reinforcement for progress, regardless of how small the progress. Provide distraction from self-absorption and diversional activities, as appropriate. Perform suicide risk assessments and institute suicide precautions, as appropriate; maintain one-on-one contact, if indicated. Develop a safety plan with the patient that includes a list of coping strategies and sources of support. Administer medications, as prescribed, keeping in mind that it may take 2 to 6 weeks for drugs to become effective. Prepare the patient for ECT if a rapid response is needed or drug therapy has failed. Monitoring Mood Suicidal ideation Energy level Sleep Self-care Social interaction Functional level Adverse effects of medications Response to treatment Associated Nursing Procedures Delusions, care of resident, long-term care Depression or hostility monitoring and precautions Electroconvulsive therapy Family therapy Group work techniques Involuntary admission to a psychiatric unit Legal patient hold Nutritional screening Oral drug administration, psychiatric patient Patient dress code for a psychiatric unit Phototherapy Psychiatric nursing assessment Reality orientation Relaxation and stress management techniques Room search, psychiatric patient Safe medication administration practices, general https://lnareference.wkhpe.com/ref/view.do?key=c88daaabe66f43251bdc79295c4c606e73163d9c&nmn=openMonographFromGlobalId&monographId… 5/8 2/1/2021 View Monograph Sharp or other restricted object management, psychiatric unit Suicide precautions Violent and assaultive patient management Voluntary admission to a psychiatric unit Patient Teaching General Include the patient's family or caregiver in your teaching, when appropriate. Provide information according to their individual communication and learning needs. Be sure to cover: disorder, diagnostic testing (to rule out physical disorder), possible underlying causes, and treatment, including psychotherapy and medications depression and effects on daily living and ability to function prescribed medications, such as SSRIs, SNRIs, or TCAs, including the drug names, dosages, schedule of administration, expected results, and duration of therapy potential adverse effects of prescribed medications, such as GI upset, sexual dysfunction, and fatigue with SSRIs and sedation, confusion, dry mouth, constipation, sexual dysfunction, and weight gain with TCAs importance of adhering to the drug regimen, including that it can take 2 to 6 weeks for drugs to exert their therapeutic effectiveness dietary restrictions, such as avoidance of tyramine-containing foods and drinks if the patient is taking MAOIs importance of maintaining ongoing follow-up care with therapy, including observations of clinical status monthly and medication evaluation every 8 to 12 weeks safety plan and the importance of utilizing the strategies and resources outlined in the safety plan warning signs of suicidal ideation and the need to notify a practitioner if any occur increased risk of suicide as medication therapy becomes effective importance of adherence to drug therapy and psychotherapy. Discharge Planning Participate as part of a multidisciplinary team to coordinate discharge planning efforts. The team may include a bedside nurse, social worker, care manager, and psychiatric counselor. Determine the appropriate posthospital setting to which the patient will be discharged. Assess the patient's and family's understanding of the diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, follow-up, and warning signs for which to seek medical attention. Evaluate how the current illness will affect the patient's independence. Identify the patient's formal and informal supports. Identify the patient's and family's goals, preferences, comprehension, and concerns about discharge. Confirm arrangements for transportation to initial follow-up appointments. Provide a list of prescribed drugs, including the dosage, prescribed time schedule, and adverse reactions to report to the practitioner. Provide the patient (and family or caregiver, as needed) with written information on the medications that the patient should take after discharge. Assess the patient's and family's understanding of each prescribed medication, including the dosage, administration, expected results, duration, and possible adverse effects. Assess the patient's ability to obtain medications; identify the party responsible for obtaining medications. Instruct the patient to provide a list of medications to the practitioner who will be caring for the patient after discharge; to update the information when the practitioner discontinues medications, changes doses, or adds new medications (including over-the-counter products); and to carry a medication list that contains all of this information at all times in the event of an emergency. Ensure that the patient and caregivers receive medical and psychiatric contact information. Provide contact information for local support groups or services. Ensure that the patient or caregiver receives a copy of the discharge instructions and that a copy is placed in the patient's medical record. Document the discharge planning evaluation in the patient's clinical record, including who was involved in discharge planning and teaching. Document the patient's understanding of the teaching provided and any need for follow-up teaching. INSERT_HANDOUTS https://lnareference.wkhpe.com/ref/view.do?key=c88daaabe66f43251bdc79295c4c606e73163d9c&nmn=openMonographFromGlobalId&monographId… 6/8 2/1/2021 View Monograph Resources American Association of Suicidology: http://www.suicidology.org American Psychiatric Association: http://www.psych.org American Psychological Association: http://www.apa.org Anxiety and Depression Association of America: http://www.adaa.org Depression.org: http://www.depression.org Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance: http://www.dbsalliance.org Families for Depression Awareness: http://www.familyaware.org Mental Health America: http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net National Alliance on Mental Illness: http://www.nami.org INSERT_CONTENT_ASSOCIATION_LOGOS Selected References 1. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2. Appleton, K. M., et al. (2015). Omega-3 fatty acids for depression in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(11), CD004692. (Level I) 3. Baker, K. G. (2020). Treating depression in adults with transcranial magnetic stimulation. Nursing, 50(5), 18– 20. Abstract | Complete Reference 4. Coryell, W. (2020). Unipolar depression in adults: Course of illness. In: UpToDate, Roy-Byrne, P. P. (Ed.). 5. Daly, E. J., et al. (2018). Efficacy and safety of intranasal esketamine adjunctive to oral antidepressant therapy in treatment-resistant depression: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(2), 139–148. (Level I) 6. Halverson, J. L., et al. (2020). “Depression” [Online]. Accessed December 2020 via the Web at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/286759-overview 7. Hoffmann, F., et al. (2016). Empathy in depression: Egocentric and altercentric biases and the role of alexithymia. Journal of Affective Disorders, 199, 23–29. (Level IV) 8. Holtzheimer, P. E. (2018). Technique for performing transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). In: UpToDate, Roy-Byrne, P. P. (Ed.). 9. Jarrett, R. B., & Vittengl, J. (2019). Unipolar depression in adults: Continuation and maintenance treatment. In: UpToDate, Roy-Byrne, P. P. (Ed.). 10. Kendler, K. S., & Gardner, C. O. (2016). Depressive vulnerability, stressful life events and episode onset of major depression: A longitudinal model. Psychological Medicine, 46(9), 1865–1874. (Level IV) 11. Lyness, J. M. (2019). Unipolar depression in adults: Assessment and diagnosis. In: UpToDate, Roy-Byrne, P. P. (Ed.). 12. Meekums, B., et al. (2015). Dance movement therapy for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(2), CD009895. (Level I) 13. Purgato, M., et al. (2014). Paroxetine versus other anti-depressive agents for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2014(4), CD006531. (Level I) 14. Qaseem, A., et al. (2016). Nonpharmacologic versus pharmacologic treatment of adult patients with major depressive disorder: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 164(5), 350–359. Accessed December 2020 via the Web at http://annals.org/aim/fullarticle/2490527/nonpharmacologic-versus-pharmacologic-treatment-adult-patientsmajor-depressive-disorder-clinical (Level VII) 15. Scott, R. L., et al. (2016). The relationship between sexual orientation and depression in a national population sample. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(23-24), 3522–3532. (Level IV) 16. Simon, G. (2019). Unipolar depression in adults and initial treatment: General principles and prognosis. In: UpToDate, Roy-Byrne, P. P. (Ed.). https://lnareference.wkhpe.com/ref/view.do?key=c88daaabe66f43251bdc79295c4c606e73163d9c&nmn=openMonographFromGlobalId&monographId… 7/8 2/1/2021 View Monograph 17. Simon, G. (2019). Unipolar major depression in adults: Choosing initial treatment. In: UpToDate, Roy-Byrne, P. P. (Ed.). 18. Thase, M., & Connolly, K. R. (2018). Unipolar treatment resistant depression in adults: Epidemiology, risk factors, assessment, and prognosis. In: UpToDate, Roy-Byrne, P. P. (Ed.). 19. Thase, M., & Connolly, K. R. (2019). Unipolar depression in adults: Management of highly resistant (refractory) depression. In: UpToDate, Roy-Byrne, P. P. (Ed.). 20. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. (2016). “VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of major depressive disorder” [Online]. Accessed December 2020 via the Web at https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/mdd/VADoDMDDCPGFINAL82916.pdf (Level VII) 21. Weatherspoon, D., et al. (2015). Pharmacology update on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and major depression. Nursing Clinics of North America, 50(4), 761–770. https://lnareference.wkhpe.com/ref/view.do?key=c88daaabe66f43251bdc79295c4c606e73163d9c&nmn=openMonographFromGlobalId&monographId… 8/8