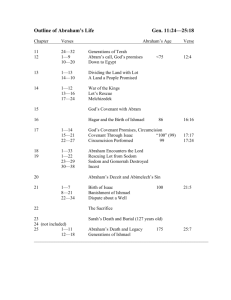

Question #1 The very first thing I noticed when reading the two creation stories was the difference in earthly mediums; the first story speaks of a “formless void” and a “wind…swept over the face of the waters” (1:1-3), while the second account speaks only of “no plant…and no herb of the field had yet sprung up” (2:5). This becomes important, because the first story goes on to display a very ordered creation through watery separation; “God made the dome and separated the waters…let the waters under the sky be gathered together in one place…” (1:6-9). The second story immediately jumps into forming man “from the dust of the ground”, and then forming a garden, animals, and a female (2:7). The writers purposely set an order to creation #1. It takes 6 days to create the world, with everything culminating in this final day with the creation of mankind. The second story comes out of disorder, and God is much more personal to human beings, even getting as close as breathing “into his nostrils the breath of life” (2:7). The first story portrays a powerful, almost distant God, while the second account has God getting up-close and personal with his creation. The second account sets the stage for a God who is more human and fallible than the first story’s God, as we can see in His struggle to find a Adam a suitable partner; “I will make him a helper…but for the man there was not found a helper [with the animals] as his partner” (2:20). Finally, the second account continues onward after the initial creation, discussing Adam and Eve’s eventual “downfall” and loss of innocence when they eat the forbidden fruit. Story one climaxes with the creation of man, and story two ends with God saying, “See, the man has become like one of us…therefore the Lord God sent him forth from the garden” (3:22). On an external level, the inclusion of two creation accounts is subversive to Babylonian culture. The first creation story is similar to the Babylonian’s Enuma Elish, so the fact that a “wind from God swept over the face of the waters” (1:2) would be a slap in the face of Babylonian religion due to its parallels to their god Marduk. Furthermore, YHWH is even more powerful in the Jewish creation account, because He is able to create the world in 7 days without fighting other gods, and he permanently “stamps his presence with time” (rough citation from Magonet). This external subversion of a culture that had oppressed the Jews was very edgy. This leads to my next point on internal subversion. Two creation accounts make people question who they believe God truly is, and what his relationship to mankind is like. Are we “created in his image…male and female” (1:27), or are we men “from the dust of the ground” (2:7)? These are two drastically different ideas of humanity. One is the pinnacle of creation, and the other is a piece of dirt, for lack of a better term. Additionally, since there are two creation accounts, one of them has to be historically “false”. This is a hard concept to digest, especially for Bible readers who view everything as divinely inspired (mostly from a Christian standpoint, I suppose). The world was either created in 7 days, or it was created faster (according to the second account). Eve was either created with Adam, or she was created from Adam’s rib. These are contradictory ideas that are subversive to a culture of Truth. They cause believers to struggle with what their concept of creation is. Genesis is especially subversive to both believers and Gentiles alike. It challenges readers and critiques to think about who they are, and who God is, and what that relationship is like. Is it a covenantal partnership, or is God omnipresent? Question #2 – Isaac Sacrifice “He said to him, ‘Abraham!’ And he said, ‘Here I am’” (22:1). Abraham is the ultimate servant to YHWH, immediately responsive to God’s calling. The next line is important due to God’s wording; “Take our son, your only son Isaac, whom you love…and offer him there as a burnt offering” (22:3). Abraham gets up the next morning, and travels for three days with his son to Moriah. Isaac and Abraham leave the other young men that had journeyed with them, and Abraham tells them, “Stay here with the donkey; the boy and I will go over there; we will worship, and then we will come back to you” (22:5). He walks with Isaac up the mountain, and when Isaac asks where the lamb is, all he says is “God himself will provide the lamb for a burnt offering, my son” (22:8). Push comes to shove, and Abraham builds an altar, binds his son Isaac, lays him on the altar, and is just about to kill him before an angel tells him to stop. The angel tells Abraham, “Do not lay your hand on the boy…for now I know that you fear God” (22:12). Abraham finds a ram to give for sacrifice, and offers it as burnt offering. The angel then appears for a second time, and tells Abraham that he will be blessed with numerous offspring. The story ends with one of the most chilling sentences I have yet to read in the Hebrew Bible; “So Abraham returned to his young men, and they arose and went together to Beer-sheba; and Abraham lived at Beer-sheba” (22:19). Burton Visotzky has a quote in his chapter “Isaac Unbound” that sums up what I think about Abraham’s morality; “In the end, Abraham is close only to God” (loose citation from The Genesis of Ethics). Abraham is not the only character at fault in this story. God is just as evil of a character, if not the most evil character, in the story of Isaac’s almost (or possible) sacrifice. The first line of the story asks questions about morality; “After these things God tested Abraham” (22:1). Why did God need to test Abraham? Had he not done everything that God had asked him to do, even if he had screwed up a few times along the way? What could God possibly gain with testing his servant by asking him to kill his only son Isac? Moral question #1: Why the heck would God do this to Abraham, and what do we have to learn from this test? Abraham’s actions are hauntingly concise. He does not protest God’s request, and he does not waiver in his actions. Did Abraham really hold YHWH above his son Isaac? It would be interesting to see what Abraham was thinking while on the three-day voyage to Moriah. Was he thinking that maybe God was finally “collecting his due”, like Visotsky speculates? Or was he a mindless robot? Finally, Abraham is able to bind Isaac to the altar. This tells me that unless Isaac was very young, he was somewhat of a participant in this sacrifice. Could perhaps Isaac be okay with giving up his life for God, if it is truly what He wants? Maybe Isaac just trusts his father so much that he is willing to give up his life for him. At the end, the story ends with a chilling paragraph because only Abraham returns to his young men. Is Isaac dead? Was he so traumatized that he left his father once Abraham unbound him? God is lacking morality in this story. As a reader, you question why God would do this to his most faithful servant. There is no rationale for this kind of action, except that God is learning too. He is not perfect, and he did not realize how traumatic this sacrifice could be. Abraham is not guiltless here, however. As a reader, you have to question why he did not tell God “no”. Sometimes the familial bond can be stronger than faith. And why did Abraham not plead with God for an easier test? This is not an easy story, and it is a difficult read as a Christian. There are lots of questions centering on morality. Question 3 In class, we mentioned that Deuteronomy seemed to have a lot “nicer” laws than Exodus. They treat slaves, women, and other minority groups better than the harsher commandments given by Moses in Exodus. Specifically, when discussing the treatment of slaves, there are key differences between the two codes that are evident when reading. Exodus commands all Hebrew slave-owners to release their slaves after 6 years of service, stating; “when you buy a male Hebrew slave, he shall serve six years, but in the seventh he shall go out a free person, without debt” (21:2). There are stipulations to this rule, however, and if the master gives his slave a wife and she bears children during his tenure, they do not go with the male slave at the end of 6 years. Harsh. Finally, “if the slave declares, ‘I love my master, my wife, and my children; I will not go out a free person’” (21:5) then the master can let the slave serve him for life. Let’s compare this to Deuteronomy; “If a member…is sold to you and works for you six years, in the seventh year you shall set that person free…you shall not send him out empty-handed. Provide liberally…” (15:12-15). This is a key difference in the treatment of slaves. Instead of just waving goodbye, Jews are now required to provide liberally for their freed slaves to get them started with their own lives. As an afternote, Deuteronomy reminds the Hebrews, “Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt” (15:15), as if to put down Jews who would be especially displeased at this more lenient commandment. Although that is the last explicit commandment YHWH gives concerning slaves, he does add one last message in Deuteronomy that provides additional leniency to an evolving Israel; “Do not consider it a hardship when you send them out from you free persons, because for six years they have given you services” (15:18). This last difference in Deuteronomy speaks to how the culture and nation of Israel is progressing towards a more industrialized society. In class, we discussed how Hammurabi’s code was incredibly detailed with casuistic law, in opposition to the Jewish apodictic 10 commandments. Deuteronomy’s additional language and leniency with slave owning tells me that more process, government, and industrialization is being introduced to Israel. With Exodus, slaves were being released after 6 years of service, but they probably soon became beggars because of their lack of job/home/security. Deuteronomy fixes this issue, makes a more detailed law concerning slaves, and increases the slaves’ ability to make a life for themselves after servitude. Hammurabi came from an incredibly advanced culture. Israel was agrarian and rural in its beginnings, as seen with the slave law and law concerning marriage (hint – women got the short end of the stick most of the time). However, with a couple centuries behind them, Israel moves into more progressive law with Deuteronomy. Slaves are treated better, process is instituted for women and men in marriage, and it is apparent that a court system is being created to enforce both civic and religious law. I shall end with Deuteronomy’s law for witnesses; “Only on the evidence of two or three witnesses shall a charge be sustained” (19:15). The fact that Deuteronomy specifies more than one witness testimony tells me that they (1) have a court system, (2) understand that witnesses can lie/forget, and (3) more than one witness is necessary in trials. This one sentence makes apparent how much progress Israel has made as a culture and a government over the couple hundred years in between Exodus and Deuteronomy.