International Trade Law: Buyer & Seller Responsibilities

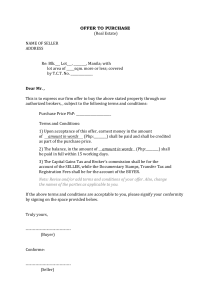

advertisement