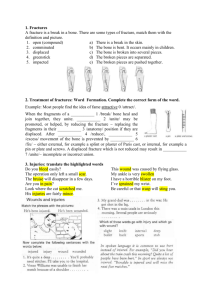

PRINCIPLES OF FRACTURES FRACTURE HEALING TREATMENT GUIDELINES Juman Abu Hazeem Definition • A Break in the structural continuity of bone. • Can be divided in to: 1. closed (or simple) If the overlying skin remains intact 2. open (or compound) fracture; if the skin is breached classification Can also be classified into: Simple fractures are fractures that only occur along one line, splitting the bone into two pieces. Comminuted (multi-fragmentary) fractures involve the bone splitting into multiple pieces Fractures result from: (1) injury (2) repetitive stress (3)abnormal weakening of the bone (‘pathological’) TYPES OF FRACTURE Complete fractures Transv erse fractur e Obliqu e spiral compa cted In-complete fractures commi nuted Examples: greens tick fractur e. Stress fractur e Compr ession. Complete Fractures • Complete Fracture- A fracture in which bone fragments separate completely bone is split into two or more fragments Complete Fractures types Transverse Fracture- A fracture that is at a right angle to the bone's long axis. Oblique Fracture- A fracture that is diagonal to a bone's long axis. Spiral Fracture- A fracture where at least one part of the bone has been twisted. The fracture pattern on x-ray can help predict behaviour after reduction how? answer: in a transverse fracture the fragments usually remain in place after reduction; if it is oblique or spiral, they tend to shorten and redisplace even if the bone is splinted (a) Transverse (b) segmental (c) spiral Complete Fractures types Compacted (impacted) Fracture- A fracture caused when bone fragments are driven into each other or(the fragmentsare jammed tightly together) and the fracture line is indistinct Comminuted Fracture. Fx, occur at two levels with free segment between them which there are more than two fragments. often unstable because there is poor interlocking of the fracture surfaces. • Segmanal fracture : 3 pieces with one piece floating Oblique fracture spiral Impacted fracture Incomplete fractures Fracture where bone is incompletely divided and the periosteum remains in continuity o In a greenstick fracture the bone is buckled or bent . o seen in children, >>>bones are more springy than those of adults. o Children can also sustain injuries where the bone is plastically deformed (misshapen) without there being any crack visible on the x-ray. Incomplete fractures Compression fractures occur when cancellous bone is crumpled. This happens in adults and typically where this type of bone structure is present, e.g. in the vertebral bodies when the front portion of a vertebra in the spine collapses due to osteoporosis calcaneum tibial plateau Greenstick fracture of radius and ulna (a) buckle or torus (b) greenstick (c)greenstick More principles A stable fracture is one which is likely to stay in a good (functional) position while it heals. An unstable Fx is likely to angulate or rotate before healing and lead to poor function in the long term Fracture of the bony components of the joint is called fracture-dislocation. – E.g. shoulder fracture dislocation and elbow fracture dislocation. Burst fracture, occur in vertebra due to severe violence, acting vertically on a straight spine. Mechanism of fracture • Most fractures are caused by sudden and excessive force 1. direct force 2. indirect force Forces With a direct force the bone breaks at the point of impact; the soft tissues also are damaged. A direct blow usually splits the bone transversely or may bend it so as to create a break with a ‘butterfly’ fragment. Damage to the overlying skin is common; if crushing occurs, the fracture pattern will be comminuted with extensive soft-tissue damage. • With an indirect force the bone breaks at a distance from where the force is applied; soft-tissue damage at the fracture site is not inevitable. • Although most fractures are due to a combination of forces (twisting, bending, compressing or tension) The x-ray pattern reveals the dominant mechanism: 1. • Twisting causes a spiral fracture 2. • Compression causes a short oblique fracture. 3. • Bending results in fracture with transversely or a triangular ‘butterfly’ fragment; 4. • Tension tends to break the bone; in some situations it may simply avulse a small fragment of bone at the points of ligament or tendon insertion Note:The above description applies mainly to the long bones. A cancellous bone, such as a vertebra or the calcaneum, when subjected to Sufficient force, will split or be crushed into an abnormal shape Soft tissue damage • It could be either: • Low energy fractures like closed spiral fractures, and it coz moderate soft tissue damage. • High energy fractures: like comminuted fractures and it coz severe tissue damage, no matter whether it open or close. Mechanism of injury Some fracture patterns suggest the causal mechanism: (a) spiral pattern (twisting); (b) short oblique pattern (compression); (c) triangular ‘butterfly’ fragment (bending) and (d) transverse pattern (tension) Spiral and some (long) oblique patterns are usually due to low-energy indirect injuries Bending and transverse patterns are caused by high-energy direct trauma FATIGUE OR STRESS FRACTURES • Defintion: These fractures occur : in normal bone which is subject to repeated heavy loading. Examples: typically in athletes, dancers or military personnel who have grueling exercise programmes • Mechanism:>>>These high loads create minute deformations that initiate the normal process of remodelling – a combination of bone resorption and new bone formation in accordance with Wolff’s law.>>>> • When exposure to stress and deformation is repeated and prolonged, resorption occurs faster than replacement and leaves the area liable to fracture A similar problem occurs in individuals who are on medication that alters the normal balance of bone resorption and replacement; stress fractures are increasingly seen in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases who are on treatment with steroids or methotrexate. Fatigue fractures – fatigue fractures, is caused by the application of abnormal stress on a bone that has normal elastic resistance, The stress placed on bone causes resorption and microfractures. – insufficiency fractures, On the other hand, occurs when normal muscular activity stresses a bone that is deficient in mineral or elastic resistance Can occur any where but most commonly 2nd metatarsal followed by Fibula and Tibia. • Clinically, Pain with gradual onset, examination will show local tenderness after weeks there will be swelling. PATHOLOGICAL FRACTURES Definition: Fractures may occur even with normal stresses if the bone has been weakened by a change in its structure (e.g. : General: in osteoporosis osteogenesis imperfecta Paget’s disease) or through a lytic lesion (e.g. a bone cyst or a metastasis). PATHOLOGICAL FRACTURES 2 Local causes • Bone infection (osteomyelitis). • Benign tumors (enchondroma, giant cell tumor). Malignant tumor (osteosarcoma , Ewing sarcoma and metastatic carcinoma). Generalized causes • Congenital (osteogenesis imperfecta). • Diffuse affection of bone (osteoporosis, rickets, uremic osteodystrophy) • Other causes (Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, Paget’s disease, Gaucher’s disease). CLASSIFICATION OF FRACTURES • Alphanumeric classification developed by Muller and colleagues has now been adapted and revised • In this system, the 1. first digit specifies the bone (1 = humerus, 2=Radius/ulna, 3 = femur,4 = tibia/fibula) 2. the second the segment (1 = proximal, 2 = diaphyseal, 3 = distal, 4 = malleolar) 3. A letter specifies the fracture pattern (for the diaphysis: A = simple, B = wedge, C = complex 4. for the metaphysis: A = extra-articular, B = partial articular,C = complete articular) • Two further numbers specify the detailed morphology of the fracture • • • • Each long bone has three segments – proximal, diaphyseal and distal; the proximal and distal segments are each defined by a square based on the widest part of the bone. ( (b,c,d) Diaphyseal fractures may be simple, wedge or complex. (e,f,g) Proximal and distal fractures may be extra-articular, partial articular of complete articular FRACTURES DISPLACEDMENT • After a complete fracture the fragments usually become displaced, partly by the force of the injury, partly by gravity and partly by the pull of muscles attached to them. • The two main fragments of fracture are commonly displaced • The causes of displacement are: – Primary impact – Gravity – Muscle pull The following Displacements are recognized: • Translation ‘’shift’’ • Length • Alignment ’’angulation’’ • Rotation ‘’ twist’’ Displacement of the fracture fragments Translation (shift) – The fragments may be shifted sideways, backward or forward in relation to each other, such that the fracture surfaces lose contact. The fracture will usually unite as long as sufficient contact between surfaces is achieved; this may occur even if reduction is imperfect, or even if the fracture ends are off-ended but the bone segments come to lie side by side. Angulation (tilt) – The fragments may be tilted or angulated in relation to each other. Malalignment, if uncorrected, may lead to deformity of the limb. • Rotation (twist) – One of the fragments may be twisted on its longitudinal axis; the bone looks straight but the limb ends up with a rotational deformity. Length – The fragments may be distracted and separated, or they may overlap, due to muscle spasm, causing shortening of the bone Rotation is NEVER acceptable Angulation and translation TO A CERTAIN DEGREE are acceptable Shortening IN PED.s TO A CERTAIN LIMIT is acceptabel FRACTURE HEALING • The process of fracture repair varies according to the type of bone involved and the amount of movement at the fracture site 1. HEALING BY CALLUS 2. HEALING BY DIRECT UNION HEALING BY CALLUS • This is the ‘natural’ form of healing in tubular bones; in the absence of rigid fixation, it proceeds in five stages: 1. Tissue destruction and haematoma formation • Vessels are torn and a haematoma forms around and within the fracture. • Bone at the fracture surfaces, deprived of a blood supply, dies back for a millimetre or two. HEALING BY CALLUS 2. Inflammation and cellular proliferation – Within 8 hours of the fracture there is an acute inflammatory reaction with migration of inflammatory cells the initiation of proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from the periosteum, the breached medullary canal and the surrounding muscle. The fragment ends are surrounded by cellular tissue,which creates a scaffold across the fracture site.vast array of inflammatory mediators (cytokines and various growth factors) is involved. The clotted haematoma is slowly absorbed and fine new capillaries grow HEALING BY CALLUS 3. Callus formation – The differentiating stem cells provide chrondrogenic and osteogenic cell populations; • given the right conditions – and this is usually the local biological and biomechanical environment – they will start forming bone or, in some cases, also cartilage. • The cell population now also includes osteoclasts (probably derived from the new blood vessels), which begin to mop up dead bone. • The thick cellular mass, with its islands of immature bone and cartilage, forms the callus or splint on the periosteal and endosteal surfaces. • As the immature fibre bone (or ‘woven’ bone) becomes more densely mineralized, movement at the fracture site decreases progressively and at about 4 weeks after injury the fracture ‘unites’. HEALING BY CALLUS 4. Consolidation – With continuing osteoclastic and osteoblastic activity the woven bone is transformed into lamellar bone. o The system is now rigid enough to allow osteoclasts to burrow through the debris at the fracture line, and close behind them. o Osteoblasts fill in the remaining gaps between the fragments with new bone. o This is a slow process and it may be several months before the bone is strong enough to carry normal loads. HEALING BY CALLUS 5. Remodelling – The fracture has been bridged by a cuff of solid bone. Over a period of months, or even years, this crude ‘weld’ is reshaped by a continuous process of alternating bone resorption and formation. Thicker lamellae are laid down where the stresses are high, unwanted buttresses are carved away and the medullary cavity is reformed. • Eventually, and especially in children, the bone reassumes something like its normal shape. HEALING BY DIRECT UNION • Clinical and experimental studies have shown that callus is the response to movement at the fracture site • It serves to stabilize the fragments as rapidly as possible – a necessary precondition for bridging by bone. • If the fracture site is absolutely immobile – for example, an impacted fracture in cancellous bone, or a fracture rigidly immobilized by a metal plate – there is no stimulus for callus HEALING BY DIRECT UNION • Instead, osteoblastic new bone formation occurs directly between the fragments. • Gaps between the fracture surfaces are invaded by new capillaries and osteoprogenitor cells growing in from the edges, and new bone is laid down on the exposed surface (gap healing). Where the crevices are very narrow (less than 200 μm), osteogenesis produces lamellar bone; wider gaps are filled first by woven bone, which is then remodelled to lamellar bone. By 3–4 weeks the fracture is solid enough to allow penetration and bridging of the area by bone remodelling units, i.e. osteoclastic ‘cutting cones’ followed by osteoblasts. • Where the exposed fracture surfaces are in intimate contact and held rigidly from the outset, internal bridging may occasionally occur without any intermediate stages (contact healing). Comparison Healing by callus, though less direct (the term‘indirect’ could be used) has distinct advantages: • it ensures mechanical strength while the bone ends heal, and with increasing stress the callus grows stronger and stronger (an example of Wolff’s law). With rigid metal fixation, on the other hand, the absence of callus means that there is a long period during which the bone depends entirely upon the metal implant for its integrity. • Moreover, the implant diverts stress away from the bone, which may become osteoporotic and not recover fully until the metal is removed. UNION, CONSOLIDATION AND NON-UNION Union – Union is incomplete repair; the ensheathing callus is calcified. Clinically the fracture site is still a little tender though the bone moves in one piece (and in that sense is united), Attempted angulation is painful. X-Rays show the fracture line still clearly visible, with fluffy callus around it. • Repair is incomplete and it is not safe to subject the unprotected bone to stress. • Consolidation – Consolidation is complete repair ;the calcified callus is ossified. Clinically the fracture: site is not tender, no movement can be obtained and attempted angulation is painless. X-rays show: the fracture line to be almost obliterated and crossed by bone trabeculae, with well-defined callus around it. Repair is complete and further protection is unnecessary • Non-union – Sometimes the normal process of fracture repair is thwarted and the bone fails to unite a) Fracture ( (b) union; (c) consolidation (d) bone remodelling Causes of non-union • (1) distraction and separation of the fragments, sometimes the result of interposition of soft tissues between the fragments; • (2) excessive movement at the fracture line; • (3) a severe injury that renders the local tissue s nonviable or nearly so; • (4) a poor local blood supply • (5) infection. Of course surgical intervention, if ill-judged, is another cause! Non-unions Non-unions are septic or aseptic. In the latter group, they can be either stiff or mobile as judged by clinical examination. The mobile ones can be as free and painless as to give the impression of a false joint (pseudoarthrosis). On x-ray, non-unions are typified by • a lucent line still present between the bone fragments; • sometimes there is exuberant callus trying but failing to bridge the gap (hypertrophic non-union) or at • times none at all (atrophic non-union) with a sorry, withered appearance to the fracture ends What is the cause of… • Atrophic non-union? Vascular supply compromise • Hypertrophic non-union? Excessive mobility= callus keeps failing • • • • Non-unions Aseptic non-unions are generally divided into hypertrophic and atrophic types. Hypertrophic non-unions often have florid streams of callus around the fracture gap – the result of insufficient stability. They are sometimes given colourful names, such as: (a) elephant’s foot. In contrast, atrophic non-unions usually arise from an impaired repair process; they are classified according to the x-ray appearance as (b) necrotic, (c) gap and (d) atrophic • Q:Timetable – How long does a fracture take to unite and to consolidate? • No precise answer is possible because age, constitution, blood supply, type of fracture and other factors all influence the time taken. Time factor • • • • • • The rate of the bone healing depends on: 1-type of the bone. 2-type of fracture. 3- blood supply 4-general constitution. 5- pt age. Average time for Upper limb healing Callus visible Lower limb union 2-3 weeks 4-6 weeks 2-3 weeks 8-12 weeks consolidation 6-8 weeks 12-16 weeks CLINICAL FEATURES • HISTORY • There is usually a history of injury, followed by inability to use the injured limb • The fracture is not always at the site of the injury: a blow to the knee may fracture the patella, femoral condyles, shaft of the femur or even acetabulum. The patient’s age mechanism of injury o . If a fracture occurs with trivial trauma, suspect a pathological lesion. o Pain, o bruising o swelling are common symptoms but they do not distinguish a fracture from a soft-tissue injury. o Deformity is much more suggestive. History 2 Always enquire about symptoms of associated injuries: pain and swelling elsewhere (it is a common mistake to get distracted by the main injury, particularly if it is severe), numbness or loss of movement, skin pallor or cyanosis, blood in the urine, abdominal pain, difficulty with breathing or transient loss of consciousness. • Once the acute emergency has been dealt with, ask about previous injuries, or any other musculoskeletal abnormality that might cause confusion when the x-ray is seen. • Finally, a general medical history is important, in preparation for anaesthesia or operation GENERAL SIGNS • Unless it is obvious from the history that the patient has sustained a localized and fairly modest injury, priority must be given to dealing with the general effects of trauma • Follow the ABCs: • look for, and if necessary attend to, Airway obstruction, Breathing problems, Circulatory problems and Cervical spine injury. • During the secondary survey it will also be necessary to exclude other previously unsuspected injuries and to be alert to any possible predisposing cause (such as Paget’s disease or a metastasis). LOCAL SIGNS • Injured tissues must be handled gently. • To elicit crepitus or abnormal movement is unnecessarily painful; x-ray diagnosis is more reliable. • Nevertheless the familiar headings of clinical examination should always be considered, or damage to arteries, nerves and ligaments may be overlooked. • A systematic approach is always helpful: 1. • Examine the most obviously injured part. 2. • Test for artery and nerve damage. 3. • Look for associated injuries in the region. 4. • Look for associated injuries in distant parts. look feel move Look • Swelling, bruising and deformity may be obvious • the skin is intact>>if the skin is broken and the wound communicates with the fracture, the injury is ‘open’ (‘compound’). • Note also the posture of the distal extremity and the colour of the skin (signs of nerve or vessel damage). Feel • The injured part is gently palpated for localized tenderness. • Some fractures would be missed if not specifically looked for • e.g. the classical sign (indeed the only clinical sign!) of a fractured scaphoid is tenderness on pressure precisely in the anatomical snuff-box. • The common and characteristic associated injuries should also be felt for, even if the patient does not complain of them. • For example, an isolated fracture of the proximal fibula should always alert to the likelihood of an associated fracture or ligament injury of the ankle • in high-energy injuries always examine the spine and pelvis. • Vascular and peripheral nerve abnormalities should be tested for both before and after treatment Move • Crepitus and abnormal movement may be present, • Q:but why inflict pain when x-rays are available? • It is more important to ask if the patient can move the joints distal to the injury. X-RAY • X-ray examination is mandatory. Remember the rule of twos: • • Two views – A fracture or a dislocation may not be seen on a single x-ray film, and at least two views (anteroposterior and lateral) must be taken. • • Two joints – In the forearm or leg, one bone may be fractured and angulated. Angulation, however, is impossible unless the other bone is also broken, or a joint dislocated. The joints above and below the fracture must both be included on the x-ray films. • • Two limbs – In children, the appearance of immature epiphyses may confuse the diagnosis of a fracture; x-rays of the uninjured limb are needed for comparison. • • Two injuries – Severe force often causes injuries at more than one level. Thus, with fractures of the calcaneum or femur it is important to also x-ray the pelvis and spine. • • Two occasions – Some fractures are notoriously difficult to detect soon after injury, but another x-ray examination a week or two later may show the lesion. Common examples are undisplaced fractures of the distal end of the clavicle, scaphoid, femoral neck and lateral malleolus, and also stress fractures and physeal injuries wherever they occur. SPECIAL IMAGING • Sometimes the fracture – or the full extent of the fracture – is not apparent on the plain x-ray. • CT may be helpful in lesions of the spine or for complex joint fractures • Eg: • of fractures in ‘difficult’ sites such as the calcaneum or acetabulum. • MRI may be the only way of showing whether a fractured vertebra is threatening to compress the spinal cord. • Radioisotope scanning is helpful in diagnosing a suspected stress fracture or other undisplaced fractures. DESCRIPTION • Diagnosing a fracture is not enough; the surgeon should picture it (and describe it) with its properties: • (1) Is it open or closed? • (2) Which bone is broken, and where? • 3) Has it involved a joint surface? • (4)What is the shape of the break? • (5) Is it stable or unstable? • (6) Is it a high-energy or a low-energy injury? And last but not least • (7) who is the person with the injury? TREATMENT OF CLOSED FRACTURES • Treat the patient, not only the fracture. • Treatment of the fracture consists of 1. manipulation to improve the position of the fragments 2. followed by splintage to hold them together until they unite; • meanwhile joint movement and function must be preserved. • Fracture healing is promoted by physiological loading of the bone>>>>so muscle activity and early weightbearing are encouraged. • These objectives are covered by three simple injunctions: 1. • Reduce. 2. • Hold. 3. • Exercise. • Two existential problems have to be overcome • The first is how to hold a fracture adequately and yet permit the patient to use the limb sufficiently; this is a conflict (Hold versus Move) that the surgeon seeks to resolve as rapidly as possible (e.g. by internal fixation). • However the surgeon also wants to avoid unnecessary risks – here is a second conflict (Speed versus Safety). • The most important factor in determining the natural tendency to heal is the state of the surrounding soft tissues and the local blood supply. The Fracture Quartet • Dual Conflict – Hold vs Move – Speed vs Safety Tscherne (Oestern and Tscherne, 1984) classification of closed injuries • • Grade 0 – a simple fracture with little or no soft tissue injury. • • Grade 1 – a fracture with superficial abrasion or bruising of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. • • Grade 2 – a more severe fracture with deep softtissue contusion and swelling. • • Grade 3 – a severe injury with marked soft-tissue damage and a threatened compartment syndrome. The more severe grades of injury are more likely to require some form of mechanical fixation; good skeletal stability aids soft-tissue recovery. REDUCTION • CLOSED REDUCTION • OPEN REDUCTION • Methods of reduction – Manipulation – Mechanical traction 1. Manipulation • Closed manipulation is suitable for 1. All minimally displaced fractures 2. Most fractures in children 3. Fractures that are likely to be stable after reduction • Unstable fractures are sometimes reduced ‘closed’ prior to mechanical fixation • Three fold maneuver: under anesthesia and muscle relaxation 1. The distal part of the limb is pulled in the line of the bone 2. The fragments are repositioned as they disengage 3. Alignment is adjusted in each plane 2. Mechanical Traction • Some fractures are difficult to reduce by manipulation • They can often be reduced by sustained mechanical traction, which then serves also to hold the fracture until it starts to unite • In some cases, rapid mechanical traction is applied prior to internal fixation 3. Open Operation • Operative reduction under direct vision is indicated: 1. When closed reduction fails 2. When there is a large articular fragment that needs accurate positioning 3. For avulsion fractures in which the fragments are held apart by muscle pull 4. When an operation is needed for associated injuries 5. When a fracture will anyhow need internal fixation to hold it Hold • Restriction of movement – – – – Prevention of displacement Alleviation of pain Promote soft-tissue healing Try to allow free movement of the unaffected parts • Splint the fracture, not the entire limb • Methods of holding reduction: – – – – – Sustained traction Cast splintage Functional bracing Internal fixation External fixation • Closed vs. operative methods 1. Sustained Traction • Traction is applied to the limb distal to the fracture, so as to exert a continuous pull in the long axis of the bone • In most cases a counterforce will be needed • Particularly useful for spiral fractures of long-bone shafts, which are easily displaced by muscle contraction • The “hold” is not perfect, but it is “safe” and the patient can “move” the joints and exercise the muscles. • The problem is the lack of “speed”complications • Traction by gravity – Eg. Fractures of the humerus • Balanced Traction – Skin traction: adhesive strapping kept in place by bandages – Skeletal traction: stiff wire/pin inserted through the bone distal to the fracture Femur fracture managed with skeletal traction and use of a Steinmann pin in the distal femur. 2. Cast Splintage • Plaster of Paris: still used as splint, esp for distal limb fractures and for most children’s fractures • “safe” (not applied too tightly or unevenly) • “speed” of union same as traction, but pt goes home sooner • “holding” is not a problem, and patients with tibial fractures can bear weight on the cast • Big drawback is that joints encased in plaster cannot “move” and are liable to stiffen. This complication can be minimized by: 1. Delayed splintage- using traction until movement has been regained, and then applying plaster 2. Starting with a cast but after a few weeks replacing it by a functional brace which permits joint movement • Most fractures are splinted, not to ensure union but to: (1) alleviate pain; (2) ensure that union takes place in good position and (3) permit early movement of the limb and a return of function. • Complications of cast splintage – Liable to appear once the patient has left the hospital; added risk of delay before the problem is attended to 1. 2. 3. 4. Tight cast Pressure sores Skin abrasion or laceration Loose cast 3. Functional Bracing • Prevents joint stiffness while still permitting fracture splintage and loading • Most commonly for fractures of the femur or tibia • Since its not very rigid, it is usually applied only when the fracture is beginning to unite – Comes out well on all four of the basic requirements: “hold” “move” “speed” “safe” 4. Internal Fixation • “holds” securely with precise reduction • “movements” can begin at once (no stiffness and edema) • “speed”: patient can leave hospital as soon as wound is healed, but full weight bearing is unsafe for some time • “safety”= biggest problem! SEPSIS!!! – Risk depends on: the patient, the surgeon, the facilities Indications for internal fixation 1. Fractures that cannot be reduced except by operation 2. Fractures that are inherently unstable and prone to re-displacement after reduction 3. Fractures that unite poorly and slowly 4. Pathological fractures 5. Multiple fractures 6. Fractures in patients who present severe nursing difficulties 1. Interfragmentary/Lag Screws: o Fixing small fragments onto the main bone 2. Kirschner Wires o Hold fragments together where fracture healing is predictably quick 3. Plates and screws o Metaphyseal fractures of long bones o Diaphyseal fractures of the radius and ulna 4. Intramedullary nails o Long bones o Locking screwsresist rotational forces • Complications of internal fixation – Most are due to poor technique, equipment, or operating conditions – Infection • Iatrogenic infection is now the most common cause of chronic osteomyelitis – Non-union • Excessive stripping of the soft tissues • unnecessary damage to the blood supply in the course of operative fixation • rigid fixation with a gap between the fragments – Implant failure – Refracture 5. External Fixation • • • • Permits adjustment of length and angulation Some allow reduction of the fracture in all 3 planes. Especially applicable to the long bones and the pelvis. Indications: 1. Fractures associated with severe soft-tissue damage where the wound can be left open for inspection, dressing, or definitive coverage. 2. Severely comminuted and unstable fractures, which can be held out to length until healing commences. 3. Fractures of the pelvis, which often cannot be controlled quickly by any other method. 4. Fractures associated with nerve or vessel damage. 5. Infected fractures, for which internal fixation might not be suitable. 6. Un-united fractures, where dead or sclerotic fragments can be excised and the remaining ends brought together in the external fixator; sometimes this is combined with elongation in the normal part of the shaft • Complications of external fixation • High degree of training and skill! Often used for the most difficult fractures increased likelihood of complications – Damage to soft-tissue structures – Over-distraction • No contact between the fragments union delayed/prevented – Pin-track infection Exercise • Restore function to the injured parts and the patient as a whole • Active Exercise, Assisted movement (continuous passive motion by machines), Functional activity • Objectives: – – – – Restore circulation Prevent soft tissue adhesions Promote fracture healing Reduce edema • Swelling tissue tension and blistering, joint stiffnes • Soft Tissue care: elevate and exercise, never dangle, never force – Preserve joint movement – Restore muscle power – Guide patient back to normal activity OPEN REDUCTION • Operative reduction of the fracture under direct vision is indicated: • (1) when closed reduction fails, either because of difficulty in controlling the fragments or because soft tissues are interposed between them; • (2) when there is a large articular fragment that needs accurate positioning • (3) for traction (avulsion) fractures in which the fragments are held apart. • As a rule, however, open reduction is merely the first step to internal fixation. OPEN FRACTURES • Initial Management – At the scene of the accident – In the hospital Types of Open Fractures • Gustilo’s classification of open fractures: – Type 1: low-energy fracture with a small, clean wound and little soft-tissue damage – Type 2: moderate-energy fracture with a clean wound more than 1 cm long, but not much soft-tissue damage and no more than moderate comminution of the fracture. – Type 3: high-energy fracture with extensive damage to skin, soft tissue and neurovascular structures, and contamination of the wound. • Type 3 A: the fractured bone can be adequately covered by soft tissue • Type 3 B: can’t be adequately covered, and there is also periosteal stripping, and severe comminution of the fracture • Type 3 C: if there is an arterial injury that needs to be repaired, regardless of the amount of other soft-tissue damage. - The incidence of wound infection - correlates directly with the extent of soft-tissue damage, <2% in type 1 >10% in type 3 - rises with increasing delay in obtaining soft tissue coverage of the fracture. Principles of Treatment of Open Fractures • All open fractures assumed to be contaminated Prevent infection! • The essentials: – – – – – Prompt wound debridement Antibiotic prophylaxis Stabilization of the fracture Early definitive wound cover Repeated examination of the limb because open fractures can also be associated with compartment syndrome Sterility and Antibiotic cover • The wound must be kept covered until the patient reaches the operating theatre • Antibiotics ASAP • Most cases: Benzylpenicillin and flucloxacillin • Even better: 2nd generation cephalosporin, every 6 hrs/48 hrs • If heavily contaminated, cover for Gram (-) organisms and anaerobes by adding gentamicin or metronidazole and continuing treatment for 4 or 5 days Debridement and Wound Excision • • • • • • • • • • • • • In the operating theatre, never in the ER! Under GA Maintain traction on injured limb and hold it still Remove clothing Replace dressing with sterile pad Clean and shave surrounding skin Remove pad and irrigate wound with A LOT of warm normal saline Do not use a tourniquet! Extend wound and excise ragged margins healthy skin edges Remove foreign materials and tissue debris Wash out wound again with warm NS (6-12 L) Remove devitalized tissue Best to leave cut nerves and tendons alone Wound Closure • “to close, or not to close” the skin= difficult decision – Uncontaminated types 1 and 2 wounds may be sutured – All other wounds: delayed primary closure – Type 3 wounds may occasionally have to be debrided more than once and skin closure may call for plastic surgery. – Skin grafting= most appropriate if the wound cant be closed w/o tension and the recipient bed is clear, free of obvious in fxn, and well vascularized Stabilization of the Fracture • Stability of the fracture is imp in – Reducing the likelihood of in fxn – Assisting in recovery of the soft tissues • Method of fixation depends on: – Degree of contamination – Length of time from injury to operation – Amount of soft tissue damage • Open fractures of all grades up to 3A treated as for closed injuries • More severe injuries: combined approach by plastic and ortho surgeons – The precise method depends on the type of soft-tissue cover that will be employed, although external fixation using a circular frame can accommodate to most problems Aftercare and Team Work • Post-op – Limb is elevated – Circulation carefully monitored – Antibiotic cover continued; swab samples will dictate whether a diff. antibiotic is needed – If wound has been left open, inspect in 2-3 days. Delayed primary suture is then often safe or, if there has been much skin loss, plastic surgery for grafting may be necessary • Teamwork – For optimal results, open fractures with skin and soft-T damage are best managed by a partnership of ortho and plastic surgeons, ideally from the outset rather than by later referral – If no plastic surgeon on site, use a digital camera for image transmission by internet to communicate and consult. That’s it