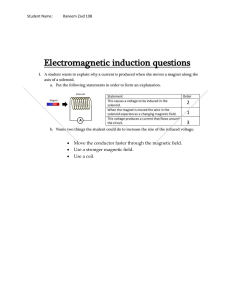

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON MAGNETICS, VOL. 48, NO. 6, JUNE 2012 2035 A New Concept of Modular Permanent Magnet and Soft Magnetic Compound Motor Dedicated to Widespread Application C. Henaux, B. Nogarede, and D. Harribey University of Toulouse, INPT—LAPLACE Toulouse 31071, France This paper deals with the design and test of a permanent-magnet machine based on a novel modular stator concept. The manufacturing and recycling costs are minimized thanks to the use of composite magnetic materials (plastic bonded magnets, soft magnetic composites). The main properties of composite magnetic materials, from a magnetic and mechanical point of view, are briefly presented in the first part of this paper. After focusing on their thermal properties by detailing a thermal experimental study, the proposed concept of a modular permanent-magnet machine is described. Experimental characterization of the realized prototype, in static and dynamic operating modes, demonstrates its advantages compared with conventional structures. Index Terms—Brushless motor, economic cost, lamination, manufacturing process, permanent-magnet motors, prototype, soft magnetic materials, temperature measurement, thermal analysis. I. INTRODUCTION ORE than 150 years after the first electrical machine prototypes were introduced, electromechanical energy conversion remains closely linked with four main concepts: DC, synchronous, induction, or switched reluctance machines. Generally based on the use of laminated magnetic circuits, classical machine structures fundamentally lie on a two-dimensional magnetic flux circulation. Manufacturers of electrical machines with low cost and mass production applications are faced with economic realities that lead to structural choices. The main objectives were first to reduce volume of materials used and manufacturing costs. To get good performance, progress in magnetic materials process manufacturing has been made in the last twenty years. We can cite in particular the use of high performance magnets in brushless motors which have replaced DC motors in most applications. Now, environmental features must be taken into account. In particular the features of recycling, which have an economic impact, cannot be ignored. If we consider the conventional structure of machine with laminated steel and classical winding coil, recycling is quite difficult or impossible. Claw pole machines provide a solution to this dilemma. Those actuators which are based on simple concentric coils integrated in a preformed stator armature are now mounted with an automatic manufacturing process that significantly reduces the cost. This configuration allows one to easily dismantle the stator and collect the coils to recycle the copper. However, their efficiency remains relatively low compare with that of the permanent-magnet brushless machine [1], [2]. The emergence of new composite magnetic materials (plastic bonded magnets, soft magnetic composites) may radically modify this situation by enabling the development of innovative machine topologies. These materials are already used in the M Manuscript received June 10, 2011; revised October 07, 2011, December 08, 2011; accepted December 12, 2011. Date of publication December 23, 2011; date of current version May 18, 2012. Corresponding author: C. Henaux (e-mail: Carole.henaux@laplace.univ-tlse.fr). Color versions of one or more of the figures in this paper are available online at http://ieeexplore.ieee.org. Digital Object Identifier 10.1109/TMAG.2011.2181530 field of static conversion [3], and electromechanical actuation [4]–[8]. Their magnetic characteristics, such as the permeability and the saturation level and their tensile strength, are still lower than the laminated steel ones. But research studies carried out in chemical compound and manufacturing (thermal cycles, compression phase, etc.) allow for significant progress [32], [33]. Replacing in conventional laminated structures by soft magnetic composites with any change of the magnetic circuit cannot yet improve the performances. But those conveniences can be compensated by the diversity of the magnetic composites manufacturing process (molding, injection or compression of massive pieces) which allows the definition of relatively sophisticated magnetic circuits making the flow of magnetic flux in three dimensions in nonconventional structures possible. In this paper, a new concept of machine made of composite magnetic materials is presented. This structure is devoted to a widespread domestic or automotive application. In Section II, the different composite magnetic materials used are studied, particularly their magnetic and thermal characteristics. The structure of the machine is then described from a technological point of view in Section III. The experimental capabilities of the prototype are given in Section IV and compared with conventional solutions. Finally, Section V describes the conclusion and perspectives of the work. II. THE COMPOSITE MAGNETIC MATERIAL In the field of magnetic materials, the technology of composites is subdivided into two main classes which respectively correspond to “passive” materials (Soft Magnetic Composites) or “active” materials (Plastic Bonded Magnets). A. The Soft Magnetic Composite—SMC SMC materials are basically iron powder particles separated with an electrically insulated coating. Those insulating particles can be pressed to form simple or complex magnetic parts. From a magnetic point of view, those compounds give the best of an interesting performance compromise in terms of magnetic saturation level and low eddy current losses. Moreover, they offer a 3-D flux carrying capability and a cost efficient production 0018-9464/$26.00 © 2011 IEEE 2036 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON MAGNETICS, VOL. 48, NO. 6, JUNE 2012 Fig. 1. B -H curves of FeSi alloys (N020) [9] and soft magnetic composite (Somaloy_700, Somaloy_550, Somaloy_700_3P), [10], Atomet EM-1 [11]. TABLE I MAIN CHARACTERISTICS OF SAMPLE process for complex 3-D parts. The last generations of soft magnetic materials are also very attractive when considering thermal and mechanical properties. 1) Magnetic Characteristics: Considering first static magnetic properties, - characteristics of SMC appear now to be relatively close to rolled material with high performances as shown in Fig. 1. 2) Thermal Characteristics and Behavior: Concerning the thermal characteristics, manufacturers provide close value of ) and lamithe thermal conductivity for SMC (20 W and 30 W nated material (between 20 W in the plane of the laminated steel). But if considering the manufacturing process of massive pieces from SMC, one can expect a lower difference between the transverse conductivity and the in-plan conductivity than for laminated magnetic circuit. Consequently a better heat dissipation could be expected in the machine structure using SMC, which makes possible the increase of the electric loading in the winding. So as to quantify this design opportunity, specific experiments have been carried out on elementary bulk parts made of various materials. The aim of those tests is not to determine the thermal conductivity of magnetic materials which is given by manufacturers, but to analyze the thermal behavior of generic magnetic parts used in magnetic circuits and build respectively from SMC and laminated material. Two SMC samples have been tested (Somaloy_700 and Somaloy_700_3P) and compared with a sample of laminated material (FeSi NO20). Their electromagnetic characteristics are summarized in Table I The Somaloy 700 and Somaloy 700_3P are manufactured in Sweden by Hoganas and are dedicated to motors. The Somaloy 700_3P compound includes organics binders and is optimized during the manufacturing process in order to get high permeability and high strength. The FeSi NO20 lamination is nonoriented silicon iron laminated material (thickness: 0.20 mm) manufactured by Arcelor industry. This thinner lamination is dedi- Fig. 2. Ferromagnetic plots with concentric coils dedicated to plan experiments for the study of thermal behavior of SMC and lamination. Fig. 3. Water-cooled dissipator fixed first at the end of the plot (test configuration no 1). cated to applications which operate at high frequency and expect low iron losses. The comparison is made on elementary concentric coil illustrated in Fig. 2. Each coil is supplied by a constant direct current. A set of temperature sensors is implemented in the samples to measure the evolution of temperature at several locations: interior copper , coil–magnetic core interface , lateral , and transcoil core surfaces. Heat is dissipated at one side of the core, verse due to a water-cooled dissipator. This dissipator has first been fixed at the end of the plot as illustrated in Fig. 3, (test configuration no 1) and secondly on its lateral surface (test configuration no 2). Experiments have been carried out with a current varying from 2 A to 5 A. The obtained results are presented in Figs. 4 and 5 with the calculated difference between the temperature lamination and SMC temperature as expressed in (1) (1) The results show that, in all the cases when considering the , the lateral temperature and the interface temperature , the Somaloy_700 have a better interior coil temperature capability of heat dissipation than laminations (the differences HENAUX et al.: NEW CONCEPT OF MODULAR PERMANENT MAGNET AND SOFT MAGNETIC COMPOUND MOTOR 2037 Fig. 5. Curves of temperature difference between lamination and SMC (test configuration no 2). (a) Magnetic core interface T . (b) Interior coil T . (c) Transverse core surface T . Fig. 4. Curves of temperature difference between lamination and SMC (test configuration no 1). (a) Magnetic core interface T . (b) Interior coil T . (c) Lateral core surface T . (d) Transverse core surface T . observed in terms of interface temperature reach 30% in favor of composite materials). results, specific Considering the transverse temperature added tests have been carried out on a laminated sample. The contact surface between the temperature sensor and the thickness of the laminated part cannot be as good as the contact in the case of the SMC pieces (the lateral side of the laminated stack is not plane). Consequently several series of measurements have been made on the laminated piece, each corresponding to a different location of the thermal sensor on the transverse face. Average temperature from those measurements has been computed to draw the final curves shown in Figs. 4(d) and 5(c). In each case, the SMC is characterized by lower temperatures. Considering the Somaloy_700_3P sample, results are less significant. Specific heat treatment, manufacturing process, and organic binders added in this type of SMC permit to improve the saturation level and the mechanical strength but globally deteriorate the thermal behavior [12]. When the heat dissipator is located on the lateral side of the sample (test configuration no 2), the results show that the thermal conductivity in the transverse direction is better in the SMC samples (the differences observed in terms of interface reach 30% in favor of composite materials). temperature The set of results show that the SMC have a better capability of heat dissipation than lamination. 2038 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON MAGNETICS, VOL. 48, NO. 6, JUNE 2012 TABLE II MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF SMC AND LAMINATED MATERIALS [10], [15], [16] Fig. 6. Shapes of plasto magnets available by injection process—Arelec manufacturer [20]. (a) Drop indicator, (b) speedometer, (c) pressure sensor. 3) Mechanical Properties: Considering the mechanical properties, the transverse rupture strength of compacted pieces is lower than in laminated materials and depends strongly on the manufacturing process and added organics binders [13], [14], [34]. A basic sample of SMC can be characterized by transverse rupture strength near 40 MPa. But the progress in manufacturing process has permitted to achieve a higher level than 100 MPa as illustrated in Table II. Concerning economics features, the energy consumption required to manufacture those soft magnetic compounds are lower than those required in the laminated material manufacturing. First the number of stages in manufacturing is limited to five for the soft magnetic compound (melting, cruding, pressing, sintering, machining). In the laminated material this number can be even higher (melting, cruding, casting process, rerolling mills, specific heat treatments, scratching, etc.) if high performances of iron steel are needed. Studies demonstrated that the energy requirements per Kg of finished part reach 25 MJ for the sintered soft magnetic compound and 50 MJ for the steel [10], [34]. Fig. 7. Shapes of feasible molded pieces (a) and unfeasible molded pieces (b). TABLE III ELECTROMAGNETIC CHARACTERISTICS OF PLASTIC BONDED MAGNETS [17]–[19] B. The Plastic Bonded Magnet If considering widespread applications, sintered Neodymium magnets still suffer from a poor tolerance in terms of high operating temperature capabilities (maximum operating temperatures to the order of 150 C). They are also extremely brittle. Therefore, taking into account corrosion problems, they do not constitute yet an adequate product for low cost applications subjected to hard environmental and mechanical conditions. Much less expensive than sintered magnets, plasto-magnets offer two attractive features, namely easy handling with satisfying magnetic characteristics (cf. Table III). Currently the manufacturing processes available (such as injection molding, compression molding, or calendering) provide materials which are more convenient to mass production processes. A large variety of shapes is accessible as illustrated in Fig. 6, particularly if injection process is used. The sizes and the shape of molded pieces are limited as shown in Fig. 7 by the matrix in the power press. Machining is even possible (subject to some precautions), which is very attractive for prototyping. The mechanical properties strongly depend on the binder and the filling ratio. Tensile strengths can achieve 100 MPa [20] which confers on this type of material a good mechanical stability and a relatively satisfactory behavior during rotation at high speed. In this context, these new materials make it possible to reconsider basic electromechanical functions, in particular when a strong functional integration is required. III. A RECYCLABLE PERMANENT-MAGNET ACTUATOR One major opportunity for composite magnetic materials in the field of electrical machines lies on new design opportunities for low cost and recyclable structures. The ferromagnetic parts in the machine can be designed to make it easy to partially cover magnetic materials such as the molded pieces (without organics binder) and copper. Even if the whole parts of the dismantled machine cannot be reused, the cost of the total dismantling will be significantly lowered. The need for an alternative solution is particularly crucial in the context of a small sized machine kW), due to an increasing techno-economic pressure and ( new environmental considerations to be satisfied in domestic or automotive appliances for instance. A. The Zigmag Concept 1) A New Winding Configuration: The proposed structure is based on a concept of a modular permanent-magnet (PM) synchronous machine with inserted winding. The stator configuration derives from a compromise between a conventional slotted stator and a claw pole stator. The slotted armature as illustrated in Fig. 8(a) permits to well magnetize the teeth which constitute a good flux guide. However, the cost of the stator manufacturing HENAUX et al.: NEW CONCEPT OF MODULAR PERMANENT MAGNET AND SOFT MAGNETIC COMPOUND MOTOR 2039 Fig. 10. Molded magnetic stator stack. Fig. 8. Stator configuration of a usual permanent-magnet machine and a claw pole permanent-magnet machine. (a) Usual slotted armature. (b) Claw pole configuration. Fig. 11. Structure of the Zigmag concept. Fig. 9. Stator configuration of the Zigmag concept and resulting elementary stator core. (a) The “zigzag” stator configuration. (b) The stator armature. is relatively expensive for low cost mass production. In the opposite, the claw pole configuration as illustrated in Fig. 8(b) is well adapted to a low cost mass production with a simple coil inserted between two stator disks. But the magnetic configuration is less efficient due to the leakage flux. In the Zigmag configuration presented in Fig. 9(a), preformed coil turns around ferromagnetic stator poles. Compared with the claw pole configuration, this zigzag shape permits to limit the leakage flux by separating the poles. The stator armature can be optimized by lying pole pieces at the end of the ferromagnetic poles and by inserting the coil in two ferromagnetic stator disks as presented in Fig. 9(b). The resulting ferromagnetic stator shape shown in Fig. 10 is feasible if using SMC by molding. Two elementary molded disks and one inserted coil are sufficient to build the stator of a single phase motor. One can notice that it is very simple to adapt the motor sizing to a wide range of power by varying the number of juxtaposed stator modules. 2) The Zigmag Actuator Design: The basic Zigmag actuator requires two stator stacks, as shown in Fig. 11. Such a stator arrangement facilitates the winding process, but also makes easy the recycling by a rapid dissociation of the various machine parts (no overlap of the conductors in the slots). The PM rotor consists of a “quasi-radial” magnetized ring molded from plasto-magnet directly on the rotor shaft. A quasiradial magnetization means that the magnet is perfectly radially magnetized along 97% of the pole pitch. It is impossible for the manufacturer to impose an ideal vertical slope between two consecutive pole for the sign inversion of the magnetic field. So 3% of the pole pitch is used to decrease the magnetic field until the zero value. The PMs used are Neoplast from Arelec ComT, pany and their characteristics are: kJ/m . They belong to the Plasto-Neodymium family discussed in Table III. The stator is constituted by stacking axially two magnetically independent modules with a circumferential shift of 90 electrical degrees from each other. The SMC used is the Somaloy_550 manufactured by Hogänas (Somaloy550-Hogänas, T). An SMC like Somaloy_700 would 2040 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON MAGNETICS, VOL. 48, NO. 6, JUNE 2012 be a better choice than Somaloy_550 but at the time of our prototype building the first one was not available [21]. As for the design of Zigmag concept, a conventional machine design approach is carried out, combining analytical and finiteelement methods. The electromagnetic torque is classically calculated by using the driving force resulting from applying the Laplace’s law. The tensile stress acting on the stator soft magnetic yokes will be calculated by the Maxwell’s force tensor in numerical computation by 3-D finite-element software. The electromagnetic torque expression is (2) with boring diameter; average value of the flux density in the air gap; Fig. 12. Mesh of Zigmag concept (only one phase). electric loading (A/m); effective axial length; TABLE IV SPECIFICATIONS AND DESIGN OF A ZIGMAG ACTUATOR winding factor. results The average value of the flux density in the air gap from the assumed sinusoidal spatial distribution of the magnetic flux density generated by the permanent magnets on the boring diameter. The molded rotor has been magnetized with six poles so that the resulting magnetic field in the air gap is quasi-sinusoidal. The analysis of the back electromotive force will validate later this assumption. The value of the electric loading has been chosen according to the natural convection during the actuator operation. The accuracy of the design mainly depends on the winding factor which is not easy to evaluate. An alternative solution consists first, in using the theory of claw pole machine using analytical methods and equivalent magnetic network [22]–[24]. Secondly, to improve the resulting equations, 3-D numerical field calculation like in many claw pole design methodology [25] is necessary to better take into account the specific configuration of the winding with preformed coils. We can see in Fig. 12 the mesh we used in our 3-D FEM analysis performed with ANSYS software. In this type of inserted coil, the contact surface between the conductors and the magnetic parts is smaller than conventional winding in slotted armature. Consequently, to exploit the heat dissipation capability of SMC (cf. Section II-A.2) by conductive heat flow, it is necessary to minimize the free space between the preformed coil and the magnetic parts. By this way the contact surface between the bore and the coils are optimized to well dissipate the losses generated in the copper using the thermal conductivity of the SMC. The resulting main dimensions are listed in Table IV. B. Dynamic Torque/Speed Characteristics and Efficiency 1) Static Tests: The actuator prototype has been tested to evaluate its electromagnetic characteristics in static and dynamic operating mode. Fig. 13 shows the static torque waveform when running the motor connected to a DC motor Fig. 13. Measure of static torque with one phase supplied by a DC current (2 A). and supplying one phase with a DC current of 2 A. From this which is the ration test we can deduce the torque constant between the peak torque and the current supply. The cogging torque has been measured and one can notice that its amplitude is less than 10% of the mean torque. The back-EMF waveform presented in Fig. 15 is obtained by running the motor connected to a DC motor at various speed and HENAUX et al.: NEW CONCEPT OF MODULAR PERMANENT MAGNET AND SOFT MAGNETIC COMPOUND MOTOR 2041 TABLE V ELECTROMAGNETIC CHARACTERISTICS OF ZIGMAG TABLE VI COMPARISON WITH UNIVERSAL AND CLAW POLE ARMATURE [30] Fig. 14. Measure of the cogging torque. Fig. 15. Electromotive force under no load condition, N = 750 rpm. getting the phase voltage. From this measure we can deduce the back EMF constant which is the ratio between the rms phase to line voltage and the rotating speed. To some extent, the preformed zigzag coil can be considered as an intermediate configuration between a fully global winding and a usual heteropolar winding. One of the major advantages of such topology lies on the minimization of magnetic leakages, compared with classical claw pole architectures [26]. The coil which turns around the teeth allows to well canalize the magnetic field in the stator and the the shape of the tooth-tips has been designed so that the leakage flux is minimized. This configuration provides a quasi-sinusoidal electromotive force from the plasto-magnet injected rotor with a “quasi-radial” polarization. The resulting waveform contains only odd harmonics whose magnitude is lower than 10% of the fundamental. The main electromechanical characteristics of the prototype are given in Table V. One can notice that it is very easy and not expensive from a designed structure to change the rated voltage by just changing the number of turns in the preformed coil. It is not the case in slotted armature which includes distributed and/or overlaps coils in slots that makes it difficult and expensive to destroy the original winding and to replace it with a new one. 2) Load Tests: To make the best of the electromagnetic stator phases decoupling, two asymmetric bridge converters are used to supply each phase coil separately. The control strategy is based on a classical hysteresis-type current regulation. The two- Fig. 16. Measure of dynamic torque on dynamic test bench. phased current references are elaborated from an integrated Hall effect position sensor, which makes it possible to drive the machine at its maximum torque. Square waves voltage are applied to each phase even though the natural waveforms generated at the output terminals are sinusoidal. Load tests are carried out with a dynamic test bench presented in Fig. 16. Considering the closed loop control operating, Figs. 17, 18, and 19 present the evolution of losses, torque, and efficiency function of the rotating speed. These results are obtained with a constant current supply of 4 A. The efficiency achieves 80% at the rated current supply. Compared with the usual efficiency obtained with classical brush DC universal or claw pole machine designed in the same power range, the efficiency of the Zigmag concept is relatively attractive with an optimal value 10% higher [27]–[29], [31]. Table VI summarizes a comparison between the Zigmag actuator and conventional universal and claw pole motors respectively mounted with SMC and laminated material. 2042 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON MAGNETICS, VOL. 48, NO. 6, JUNE 2012 Fig. 17. Copper, magnetic, and stray losses for a 4 A power supply current. Fig. 20. Current and voltage waveforms at load operation (open loop control). Fig. 18. Torque versus speed curve for a power supply current fixed to 4 A. Fig. 19. Global efficiency (motor and power supply) for a constant 4 A supply current. In the same power range, compared with the optimized brushless motor, the efficiency of the Zigmag concept is lower. But the manufacturing process of the Zigmag concept which can be built by molding or injection, can be very attractive in widespread application where the manufacturing cost is paramount. One can observe on Figs. 17 and 19 a singular point near 8500 rpm. This is due to the magtrol dynamic test bench which is unstable for this rotating speed. The resulting raise on the losses does not come from the Zigmag actuator operating. A sensorless control has been tested in the application to compare the Zigmag concept with the other kind of machines mentioned previously used in widespread appliances. When the sensorless and open loop control is applied, the current waveforms are still quasi-sinusoidal as shown in Fig. 20. Those quasi-sinusoidal natural waveforms (EMF shown in Fig. 15 and line current shown in Fig. 17) permit to limit the torque ripple in the machine (12% of the rated torque). The efficiency decreases from 80% as presented in Fig. 18 to 65% at a rated rotating speed of 8000 rpm. IV. CONCLUSION A new concept of machine based on composite magnetic materials and modular stator has been presented. This concept potentially constitutes an alternative to classical DC brush actuators in the 0.1–1 kW power range for low cost and widespread application. The specificity of the proposed topology lies on the use of SMC stator parts to constitute a modular, low cost, and recyclable motor structure. These SMC materials have been characterized from a thermal and mechanical point of view and compared to laminated material. The thermal characteristics of SMC seem to be more attractive than laminated material in the three dimensions of space. On the other hand, the mechanical characteristics are less interesting. The characterization of the realized prototype demonstrates the promising capability of the Zigmag concept when considering in particular its relatively high efficiency at high speed. From these first and promising results, a shape optimization of the stator parts, including the preformed “zigzag” coil, is now to be carried out. REFERENCES [1] F. Zhang, H. Bai, H. P. Gruenberger, and E. Nolle, “Comparative study on claw pole electrical machine with different structure,” in 2nd IEEE Conf. Industrial Electronic and Applications, ICIEA, Harbin, China, May 23–27, 2007, pp. 636–640. [2] Y. Huang et al., “Design and analysis of a high-speed claw pole motor with soft magnetic composite core,” IEEE Trans. Magn., vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 2492–2494, Jun. 2007. [3] L. O. Hultman and A. Jack, “Soft magnetic composites materials and application,” in ICEMDC’03, Jun. 2003, vol. 1, p. 516. [4] B. Slusarek, P. Gawrys, J. Z. Gromek, and M. Przybylski, “The application of powder magnetic circuits in electric machines,” in Int. Conf. Electric Machines (ICEM), Vilamoura, Portugal, Sep. 6–9, 2008. [5] Y. G. Guo, J. G. Zhu, P. A. Watterson, and W. Wu, “Development of a PM transverse flux motor with soft magnetic composite core,” IEEE Trans. Energy Convers., vol. 2, pp. 426–434, June 2006. [6] Q.-L. Deng, X. Peng, and W. Xie, “Design of axial magnet synchronous generators with soft magnetic compound (SMC) stator core,” in ICEET’09 Int. Conf. Energy and Environment Technology, Guilin, Guangxi, Oct. 16–18, 2009. [7] G. Jack, B. C. Mecrow, P. G. Dickinson, D. Stephenson, J. S. Burdess, N. Fawcett, and J. T. Evans, “Permanent-magnet machines with powdered iron cores and prepressed windings,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl., vol. 36, p. 1077, 2000. [8] Y. G. Guo, J. G. Zhu, P. A. Watterson, and W. Wu, “Comparative study of 3D flux electrical machines with soft magnetic composite cores,” in Industry Applications Conf. 37th IAS Annu. Meeting, 2002, vol. 2, p. 1147. [9] [Online]. Available: www.arcelormittal.com [10] [Online]. Available: www.Hoganas.com SMC, technical specifications, 2004 [11] Quebec Métal Powders Limited, Caractéristiques Techniques De La Poudre Magnétique ATOMET EM-1 Canada, 1999. [12] I. Gilbert, S. Bull, T. Evans, A. Jack, D. Stephenson, and A. De Se, “Effects of processing upon the properties of soft magnetic composites for low loss applications,” J. Mater. Sci., vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 457–461, 2004. HENAUX et al.: NEW CONCEPT OF MODULAR PERMANENT MAGNET AND SOFT MAGNETIC COMPOUND MOTOR [13] L. Hultman and O. Andersson, Advances in SMC Technology—Materials and Applications Copenhagen, Denmark, Tech. rep. presented in EURO PM2009, Oct. 13, 2009. [14] M. R. Dubois, L.-P. Lefebvre, P. Lemieux, and E. Dusablon, “Compaction of SMC powders for high saturation flux density,” in ICEM, Cracow, Poland, 2004. [15] Quebec Metal Powders, ATOMET-EM1, technical specifications, 2001. [16] [Online]. Available: //qmp-powders.com/fr [17] [Online]. Available: www.goudsmit-magnetics.nl [18] [Online]. Available: //ecs-global.de [19] [Online]. Available: www.magnete.de [20] [Online]. Available: www.arelec.com [21] B. Nogarede and D. Trinh-Xuan, “Moteur Électrique Synchrone,” European Patent 05001411.7 25/01/2005, Société Electronique Bobinage Aquitaine. [22] J. Cros, J. R. Figueroa, and P. Viarouge, “Analytical method of polyphase claw pole machines,” in IAS Annual Meeting No. 39, Seattle, WA, 2004. [23] S.-H. Lee, S.-O. Kwon, J.-J. Lee, and J.-P. Hong, “Characteristic analysis of claw-pole machine using improved equivalent magnetic circuit,” IEEE Trans. Magn., vol. 45, no. 10, pp. 4570–4573, Oct. 2009. [24] R. Qu, G. B. Kliman, and R. Carl, “Split-phase claw-pole induction machines with soft magnetic composites cores,” in Industry Applications Conf., 39th IAS Annual Meeting, Oct. 2004, vol. 4, p. 2514. [25] Y. G. Guo, J. G. Zhu, and H. Y. Lu, “Accurate determination of parameters of a claw-pole motor with SMC stator core by finite-element magnetic filed analysis,” in IEE Proc. Elect. Power Appl., Jul. 2006, vol. 153, no. 4, pp. 185–195. [26] Y. Enomoto, H. Tokoi, K. Kobayashi, H. Amano, C. Ishihara, and K. Abe, “Development of claw teeth motor using high-density soft magmetic composite,” Trans. Ind. Appl., Inst. Elect. Eng. Jpn., vol. 129, no. 10, 2009. 2043 [27] K. J. Bradley and W. M. H. Ismail, “The performance analysis of the single phase, AC commutator-motor,” in Proc. 5th Int. Conf Electrical Machines and Drives, 1991, pp. 146–150. [28] A. Jack, P. Dickinson, B. Mecrow, P. Jansson, and L. Hultman, “A scoping study for universal motors with soft magntic composite stators,” presented at the Int. Congr. Electrical Machines, ICEM’2000, Espoo, Finland, Aug. 28–30, 2000. [29] A. Andriollo, M. Bettanini, and G. Tortella, “Single-phase axial flux claw pole motor for high efficiency applications,” in XIX Int. Conf. Electrical Machines (ICEM), Roma, Italy, Sep. 6–9, 2010. [30] J. Cros, P. Viarouge, Y. Chalifour, and J. Figueroa, “A new structure of universal motor using soft magnetic composites,” IEEE Trans, Ind, Appl,, vol. 40, pp. 550–557, 2004. [31] Y. Guo, J. Zhu, and D. G. Dorrell, “Design and analysis of a claw pole permanent magnet motor with molded soft magnetic composite core,” IEEE Trans, Magn., vol. 45, no. 10, pp. 4582–4585, Oct. 2010. [32] P. Kollar, J. Fuzer, R. Bures, and M. Faberova, “AC magnetic properties of Fe-based composite materials,” IEEE Trans. Magn., vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 467–470, Feb. 2010. [33] I. Hemmati, H. R. M. Hsseini, and A. Kianvash, “The correlations between processing parameters and magnetic properties of an iron resin soft magnetic composite,” J. Magn. Mater., vol. 305, pp. 147–151, 2006. [34] [Online]. Available: www.metalpowder.com [35] V. Kruzhanov and V. Arnhold, “Energy consumption in the mass production of PM components,” in PM.11 Int. Conf. Powder Metallurgy for Automotive and Engineering Industry, India, Feb. 3–5, 2011.