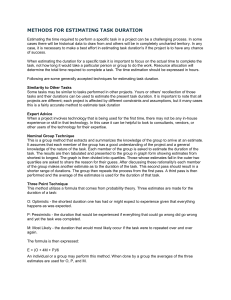

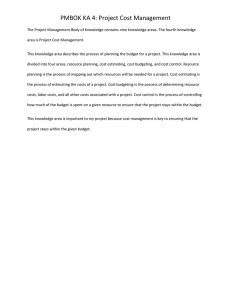

Project Goal Cost Estimating and Budgeting Vasenai Kereni SME, CEST Introduction • Cost estimates, budgets, WBSs, and schedules are interrelated. • Ideally, cost estimates are based upon elements of the WBS and are prepared at the work package level. • When the cost cannot be estimated because it is too complex, the task is broken down further until it can. • When the cost cannot be estimated because the work is illdefined or uncertain, the estimate is initially based upon judgment and later is revised as information becomes available. COST ESTIMATES • The initial cost estimate can seal the project’s financial fate. When project costs are overestimated, the contractor risks losing the job to a lower-bidding competitor. • Worse is when they are underestimated. • Cost estimates are used to develop budgets. After the project begins, actual costs are compared to estimated costs (indicated by the budget) as one measure of the project’s work performance. • Without good estimates, it is impossible to evaluate work efficiency or to determine in advance how much the project will cost at completion. COST ESCALATION • The amount by which actual costs grow to exceed initial estimates • The larger and more complex the project, the greater is the potential for escalation. • The costs of cutting-edge technology and research projects frequently escalate by upwards of several hundred percent COST ESTIMATING AND THE SYSTEMS DEVELOPMENT CYCLE • The first estimate is made during project conception. Since very little hard cost information is available at that time, the estimate is the least reliable that it will ever be. • If the project is unique and ill defined, uncertainty in cost estimates often dictates that contracts will be of the cost-plus kind. • As more aspects of the system and project are defined, the material costs, labor times, and labor rates can be nailed down, and cost estimates become more reliable • When the system and project are fairly routine, the estimates are somewhat reliable and contractors are willing to accept incentive-type or fixed-price contracts. LIFE CYCLE COSTS • Life cycle costs (LCC) represent all the costs of a system, facility, or product throughout its life cycle, cradle to grave. • LCC include costs for the other phases of the system life cycle—the operation phase and eventual disposal of the end-item, and, sometimes, the conception phase too (initiation and feasibility). • Anticipating LCC is necessary because costs influence so many decisions. • For example, suppose three contractors submit proposals to build a plant, and each proposal contains not only the plant’s construction cost but also its expected operating costs. If the bids are similar in terms of construction costs and plant features, the one with the lowest operating costs will likely win. LIFE CYCLE COSTS • The LCC similarly affect decisions regarding development projects, and feasibility studies should consider all costs for acquisition, operation, maintenance, and disposal of the system or product. • Estimating LCC involves making assumptions about technology, market, and product demand, and relies on historical costs of similar systems and projects; still, it is a sensible way to approach projects, especially when there is a choice between alternative designs or proposals. • The LCC should also account for the time necessary to develop, build, and install the end-item—i.e., the time before the facility or system becomes operational or the product is “launched” to market. COST ESTIMATING PROCESS • Estimate versus Target or Goal • Sometimes the word “estimate” is confused with “target” and “goal.” It shouldn’t. • Whereas an estimate is a realistic assessment based upon known facts about the work, required resources, constraints, and the environment, and is derived from estimating methods, a target or goal is a desired outcome or commitment. COST ESTIMATING PROCESS cont.’ • Accuracy versus Precision • “Accuracy” represents the closeness of an estimated value to the actual value: the accuracy of a $99,000 estimate for a project that actually cost $100,000 is very good. • “Precision” is the number of decimal places in the estimate. An estimate of $75,321 is more precise than one of $75,000 (though neither is accurate if the actual cost is $100,000). • Accuracy matters more than precision: the aim is to derive the most accurate estimate possible. COST ESTIMATING PROCESS cont.’ • Sometimes accuracy can be improved by employing a so-called threepoint estimate, which combines optimistic (a), pessimistic (b), and most likely cost estimates (m) to arrive at an expected cost estimate— analogous to the PERT approach for computing expected time: COST ESTIMATING PROCESS cont.’ • Expert Judgment • An expert judgment is an estimate provided by an expert—someone who, from breadth of experience or expertise, is able to provide a reasonable ballpark estimate. • It is a “seat of the pants” estimate used whenever lack of information precludes more rigorous cost analysis. • Expert opinion is usually restricted to estimates made during the conception phase, and for projects that are poorly-defined or unique and for which there are no previous similar projects for comparison. COST ESTIMATING PROCESS cont.’ • Analogous Estimate • An analogous estimate is developed by reviewing costs from previous, similar projects. • The method can be used at any level: overall project cost can be estimated from the cost of an analogous project; work package cost can be estimated from analogous work packages; and task cost can be estimated from analogous tasks. • The cost for a similar project or work package is analyzed and adjusted for differences between it and the proposed project or work package, taking into account differences in project scale, locations, dates, complexity, exchange rates, and so on. If, for example, the analogy project was performed 2 years ago and the proposed project is to commence a year from now, the analogy project cost must be adjusted to account for inflation and price changes during the 3-year interim. COST ESTIMATING PROCESS cont.’ • Parametric Estimate • A parametric estimate is derived from an empirical or mathematical relationship. The method can be used with an analogy project to scale costs up or down, or it can be applied directly without an analogy project when costs are a function of system or project “parameters.” • The parameters can be physical features, such as area, volume, weight, or capacity, or performance features, such as speed, rate of output, power, or strength. The method is especially useful when early design features are first being set and an estimate is needed quickly. COST ESTIMATING PROCESS cont.’ • Cost Engineering • Cost engineering refers to a detailed cost analysis of individual cost categories at the work package or activity level. • A bottom-up approach, it provides the most accurate estimates of all the methods, but it is also the most time-consuming. • The method requires detailed work-definition information that, often, is not available early in the project. It first divides the project into activities or work packages (e.g., from the WBS), then divides each of these into cost categories. COST ESTIMATING PROCESS cont.’ • Top-down versus Bottom-up • In general, estimating can occur in two ways: top-down and bottomup. • Top-down refers to estimating the cost by looking at the project as a whole. A top-down estimate is typically based upon an expert opinion or analogy to other similar projects. • Bottom-up refers to estimating the costs by looking at elements of the project—individual work packages and end-item components. Costs for each work package or end-item element are estimated separately and then aggregated to derive the total project cost. COST ESTIMATING PROCESS cont.’ • Reducing Costs • To reconcile differences between gross and final estimates, managers sometimes exercise an across-the-board cut on all estimates. • This is poor practice, because it fails to account for judgmental errors or excessive costs on the part of just a few units. It also unfairly penalizes managers who tried to produce fair estimates and were honest enough not to pad them. Such indiscriminate, across-theboard cuts induce everyone to pad estimates for their own protection ELEMENTS OF BUDGETS AND ESTIMATES • Budgets and cost estimates are the same in that both state the cost of doing something. • The difference is that the estimate comes first and is the basis for the budget. • An estimate may have to be refined many times, but once approved it becomes the budget. ELEMENTS OF BUDGETS AND ESTIMATES cont.’ • Estimates and budgets share the following elements: • Direct labor expense • Direct non-labor expense • Overhead expense • General and administrative expense • Profit and total billing. PROJECT COST ACCOUNTING SYSTEMS • A project is a system of sometimes hundreds or thousands of elements—workers, materials, and facilities—all which must be estimated, budgeted, and controlled. • To expedite the process, reduce confusion, and improve accuracy, you need another system; in particular, one to help compute estimates, create, store and process budgets, and track costs. Such a system, called a project cost accounting system (PCAS) PROJECT COST ACCOUNTING SYSTEMS cont.’ • PCAS is initially set up by the project manager, project accountant or PMO. • While the main focus of the PCAS is on project costs, the system also assists tracking and controlling schedules and work progress. • When a PCAS is combined with other project planning, control, and reporting functions, the whole system is referred to as the project management information system (PMIS). COST SCHEDULES AND FORECASTS • Cost Analysis with Early and Late Start Times • A simplifying assumption used in cost estimating is that costs in each work package are incurred uniformly. • For example, a 2-week, $22,000 work package is assumed to have expenditures of $11,000 per week. With this assumption, it is easy to create a cost schedule that shows the cost each week of the entire project. • Effect of Late Start Time on Project Net Worth • Owing to the time value of money, the cost of work done farther in the future has a lower net present worth than the same work if done earlier. • Delaying activities in a lengthy project can thus provide substantial savings in the present worth of project costs. SUMMARY • Cost estimation and budgeting are part of the project planning process. • Cost estimation logically follows work breakdown and precedes project budgeting. • Accurate cost estimates are necessary to establish realistic budgets and to provide standards against which to measure actual costs; they are thus crucial to the financial success of the project. • Costs in projects have a tendency to escalate beyond original estimates. Defining clear requirements and work tasks, employing skilled estimators, being realistic in estimating, and anticipating escalation causes such as inflation all help to minimize escalation. SUMMARY cont.’ • The project budget is subdivided into smaller budgets called control accounts. • Control accounts are derived from the WBS and project organization hierarchies, and are the budget equivalent to work packages. In large projects, a systematic methodology or project cost accounting system (PCAS) is useful for aggregating estimates and maintaining a system of control accounts for budgeting and control. SUMMARY cont.’ • Cost schedules are derived from time-phased budgets, and show the pattern of costs and expenditures throughout the project. They are used to identify cash and working capital requirements for labor, materials, and equipment. • Forecast project expenditures and other cash outflows are compared to schedule payment receipts and income sources to predict cash fl ow throughout the project. • Ideally, expenditures and income are balanced so that the contractor can maintain a positive cash flow. The forecasts are used to prepare a plan that guarantees adequate funding support for the project. Any QUESTIONS?