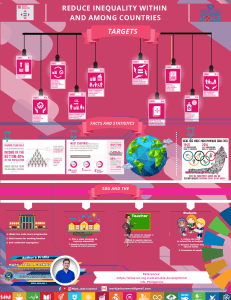

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a ‘policy roadmap’1 to holistically integrate social, economic and environmental developmental objectives under the auspices of achieving a sustainable world.2 Sustainable development has no universal consensus regarding the tangible definition within international law, as a An integrated approach to the implementation of these goals is required to materialise shared prosperity across countries and communities.3 This necessitates highlighting synergies amongst the individual goals, and enunciating trade-offs in order to overcome the difficulties that have been faced, to accelerate progress towards equitable ecological development to preserve the Earth for current and future generations.4 SDGs, internationally and regionally, are implemented systematically through international environmental instruments.5 Therefore, this essay will begin by assessing the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), this directly integrates SDGs through Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC),6 and through preventative deforestation measures under REDD+ agreements.7 Secondly, the United National Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides a potential framework to impact marine ecosystems and biodiversity.8 Furthermore, a hypothesised new instrument could provide a systemic framework to combat plastic pollutions as current instruments fall short of concrete governance to combat this ubiquitous, transboundary threat.9 Given the global failings to achieve goals of 2020, the successive time frame is critical to set the world on course for a better future.10 Louis J. Kotzé and Duncan French, ‘The Anthropocentric ontology of international environmental law and sustainable development goals: towards an ecocentric rule of law in the Anthropocene’ (2018) 7 Global Journal of Comparative Law 5, 7. 2 United Nations, ‘Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ UN Doc A/RES/70/1 (25 September 2015) Preamble para 3. 3 Ibid 39 [85]. 4 Riccardo Pavoni and Dario Piselli, ‘The Sustainable development goals and international environmental law: normative value and changes for implementation’ (2016) 13 (26) Veredas do Direito 13, 16 ; Luis GomezEcheverri, ‘Climate and development: enhancing impact through stronger linkages in the implementation of the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)’ (2018) Philosophical Transactions A 376, 379. 5 Pavoni and Piselli (n 4) 43. 6 Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, opened for signature 22 April 2016 (entered into force 4 November 2016) art 4.2. 7 Ibid art 5.2. 8 Marcus Haward, ‘Plastic pollution of the world’s seas and oceans as a contemporary challenge in ocean governance’ (2018) 9 Natur Communications 667, 668. 9 Giulia Carlini and Konstantin Kleine, ‘Advancing the international regulation of plastic pollution beyond the UN Environment Assembly resolution on marine litter and microplastics’ (2018) 27 (3) Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law 234, 239. 1 10 The Sustainable Development Goals In 2015 the United Nations deliberated over the implementation of sustainable development policies to address the unfinished business of the Millennium Development Goals.11 The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, sets outs the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which herald a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the environment and improve the lives and prospects of everyone, everywhere.12Establishing an unprecedented effort to positively identify the reciprocal interactions between the various components of sustainability:13 the 17 development goals with the correlating 169 indicators lay the path to achieve this sustainability. At the softest end of the international law continuum, these goals confer no obligations, rather specify vague and aspirational outcomes to improving the social, economic and environmental functions of the global, and national, development.14 Differing from the rigid and complex institutions of governance for climate stability and biodiversity conservation,15 the goal-setting approach to governance is beneficial in allowing states the flexibility in implementation.16 Under the SDGs, the schism between the developed and the developing States is removed: all countries are considered ‘developing’ necessitating plans to transform societies towards a more sustainable route.17 The aim is to provide States with specific, manageable and action-orientated indicators towards the SDG targets providing a management tool to develop implementation strategies and allocate resources accordingly.18 Over time as expertise, scientific certainty and technological advances grow, these developmental goals will become more specific and effective in creating coherence amongst the array of the many multilateral environmental treaties.19 Concerningly in examination of the progress within the five years following the implementation of these principles, environmental issues related to climate action (SDG 13), 11 https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20 Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf 12 Art 1 SDGs and IEL 14 Follow-up and review 15 Global governance through goal setting 16 Corporate actors 17 Global gov thru goal setting 18 Ensure co-benefits 19 Global pact 13 life on land (SDG 15), life below water (SDG 14) and responsible consumption and production (SDG 12) are the last developmental priority of world leaders.20 Directly relating to environmental deterioration, these goals are critically important given that the environment is the boundary of social and economic development as opposed to a co-equal pillar of sustainable development.21 As such, further efforts are required into developing practical frameworks to identify the interlinkages between and amongst these goals.22 These synergies are essential to effective implementation, by enunciating how environmental developmental goals will influence social and economic development reframes the approach to sustainable development to reflect the new world reality when faced with the biggest threat to global existence, climate change.23 The 2030 Agenda makes it evident that the normative framework to achieve the SDGs is to be set out under international instruments, for the purposes of this discussion those in the environmental sector.24 Paris Agreement Climate change, one of the biggest, if not the biggest, threat of the twenty first century,25 could negate all developmental efforts to eradicate poverty (SDG 1) and to improve equality (SDG 5) if the ambitious goals under the Paris Agreement of the UNFCCC are not met.26 The Paris Agreement was ratified in 2015 at the 25th Conference of the Parties, and is on track to enter into force in 2021.27 States are required under the agreement to make NDCs to reduce greenhouse gases emitted in order to reach the target of maintaining the global temperature to below 1.5°C by 2100.28 These targets are critical for the achievement of the SDGs. Sustainable development is incongruent with inertia against climate change, not merely because it fails to meet SDG 13 ‘climate change mitigation’, but because the resultant environmental deterioration directly impacts upon almost every SDG.29 A study into the synergies and trade-offs notes that there are four-times fewer trade-offs between climate action and the implementation of the SDGs.30 The trade-offs identified include the 20 New realities require new priorities New realities 22 Climate action and SDGs 23 Bridging funding gaps; reinvigorating SD 24 UN SG at Paris Agreement Resolution 70/1 25 Verner et al 2016 26 New realities require new priorities 27 Check these statements 21 28 29 30 Ensuring co-benefits; climate and development; climate action with SDG Climate action with SDG macroeconomic cost of climate mitigation which could slow development, and the impairment upon carbon-intensive industries and communities;31 given that the ultimate goal is to achieve zero net carbon emissions by 2050 these concessions hardly justify inactivity.32 The NDCs of Member States outlining national climate policy could explicitly include assessments of the synergies and trade-offs of the policy with the SDGs being nationally implemented.33 Under the Paris Agreement, the States will have the opportunity to review and update their NDCs prior to the 26th Conference of the Parties at the end of 2020.34 During this time, States will be able to enumerate synergies between the policy actions within the reports. This will assist in the monitoring of the SDG action nationally, and will enable non-State actors to hold States accountable to commitments under NDCs and SDGs.35 A framework of guidelines may be developed by the IPPC to connect climate action to the SDGs in order to assess the sustainability of such interventions.36 Reinvigorated under the Paris Agreement, ‘reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries’ (REDD+) enables policy development around mitigation outcomes towards NDCs.37 These policy agreements aim to achieve reduction in GHG emissions by the forest sector within countries with large emissions resulting from deforestation.38 Deforestation is the second largest anthropogenic source of carbon dioxide and agricultural expansion remains the largest driver of deforestation in tropical climates (where forests, and the contained biodiversity is the greatest).39 Consequently, forest protections are a key climate change mitigation tool, directly enabling countries to advance SDG 13, and SDG 15 in the sustainable management of forests.40 REDD+ is a Payments for Ecosystems Services system conferring economic rewards to resource managers who secure the provision of ecosystem services, plainly those 31 32 676 Sustainable development goal report 2019 48. 33 34 35 Examining alignment Climate action and SDG 37 Conserving carbon 38 SDGs and REDD 39 A policy nexus approach to forests and SDGs 40 Forest for SD; SDG and REDD 36 who prohibit deforestation and degradation.41 These rewards, in the form of carbon offset credits, are sold to buyers (generally the Global North). By incentivising developing states to protect forests from destruction with international financing for conservation efforts, REDD+ promotes the sustainable management of forests.42 The just implementation of these projects is upheld through the Cancun Safeguards, requiring ‘free, prior and informed consent’ of the indigenous peoples who habit the forest area.43 Given the broad beneficial impact on environmental sustainable development, REDD+ provides an accessible, accredited means of implementing SDG target and conversely, SDGs provide politically powerful rationale to expand REDD+ beyond carbon reduction objectives.44 Ocean Governance The ocean contains ? of the biological diversity of the planet, and it acts as a sink for approximately 50% of the carbon released globally.45 Due to marine pollution, and unsustainable overfishing, acidification of the ocean has increased by 26% is placing immense pressure upon marine ecosystems. The causative burdens on marine resources, which many communities are dependent, impacts upon to economic development: namely decent work (SDG 8), innovative industries (SDG 9), sustainable cities (SDG 11) and agriculture (SDG 15).46 Currently, sustainable use of marine resources is difficult to govern as the institutional system of management of human activities is fragmented.47 A revamping of the governance framework under UNCLOS proposed to consider the ‘conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdictions’ (BBNJ).48 The negotiations under the Intergovernmental Conference on BBNJ are still in progress: the final sitting is to be held in the first half of 2020,49 and provide an opportunity to advance innovative models of ocean governance to place parameters on the high seas so it is no longer an area ‘free for all to use and abuse’.50 41 Assessing the progress of REDD 42 43 44 SDG and REDD 45 46 47 Mapping linkages between oceans Achieving SDGs for oceans; once and future 48 Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 24 December 2017 A/RES/72/249 https://undocs.org/en/a/res/72/249 49 50 Ocean plastics. Firstly, the imposition of a registry of commitments on action for ocean sustainability would offer a reference for the efforts of States and intergovernmental agreements.51 State reporting is essential in conferring accountability and transparency: the voluntary reporting required of States under SDG predecessor, Agenda 21, establish the need for clear incentives for reporting.52 The reports could be made to the UN Division for Ocean Affairs and Law of the Sea, which would set up a repository of innovative solutions and lessons learned from competent global and regional organisations.53 The accessibility of data and information sharing would enable States to systematically assess action to implement SDG 14, which indirectly fosters SDG 16 through equal access to knowledge and transparency in governance.54 Commitments to sustainability may coincide with the conducting of Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) by States undertaking the activity within the ocean region. During negotiations for the improved framework, developing countries proposed the mandatory review of EIA submitted by States by a scientific community.55 Review would ensure that activities conducted in the ocean adhere to sustainable practice guidelines, however, some developed countries expressed reservations of fostering a sense of mistrust in the conducting of initial assessments.56 Negotiations centred primarily on the fair and equitable benefit sharing of resources sourced from the oceans.57 This emerging principle of international law, thus far confined to the Convention on Biological Diversity, rooted in the principle of equity, manifests a consensus among the developed and developing countries on a balance between rights and duties under the law.58 This benefit sharing could link international use of resources and local benefits from traditional knowledge holders as an ecosystem approach.59 The result could impact upon raising the standard of living of all members of society through economic progress for instances linking to SDGs through the right to food (SDG 2) and health (SDG 3), and the right to science would enable people to take equal part in political or cultural life unreservedly linking to education (SDG 4), decent work (SDG 8) and equality (SDG 10).60 51 Achieving SDGs Follow-up and review 53 Achieving SDGs 54 Using SDG towards a better understanding 55 Once and future 52 56 57 58 Fair and equitable benefit sharing under; connecting SDG 14 Connecting sdg 14; once and future 60 Fair and equitable 59 Implementation of this benefit sharing may be operationalised through marine ecosystem services, (define), by the use of marine spatial planning to create the rights over marine spaces and resources.61 There appeared to be agreement to an extent between States on the need for a meaningful benefit sharing system to prevent private sector bio-prospecting.62 A point of contention remained in the failure to rectify the whether the right to access marine genetic resources would be underpinned by the principle of common heritage of mankind, or the old ‘freedom of the high seas’.63 Whilst this equitable approach is provided under the CBD, inclusion in this new treaty would expand upon the implementation of the SDGs within international environmental instruments and codify it in the area of ocean governance. Notably, the first negotiations were silent on the issues of marine plastic pollution and ocean acidification. This detrimental, transboundary issue has the potential to ‘act as a binding catalyst for a final agreement’ in these negotiations.64 The current UNCLOS regime requires States to prevent and reduce pollution of marine environment from any source,65 though laws and regulations to control pollution from land-based sources.66 This could act as a basis for the implementation of immediate collective action against the ever growing marine pollution, which the negatively impacts economic, social and environmental development.67 Academics have argued that the framing of the convention however is too common: it omits measures of production, transport, trade and end-off life treatment of plastics, and would focus narrowly on marine pollution.68 As the sole international instrument imposing binding obligations on States regarding plastic pollution,69 and as negotiations are current, the governance over plastic pollution may be best dealt with under the revamping of UNCLOS. A new plastics treaty ? In light of the severity of plastic pollution and the destructive environmental impacts on every ecosystem, it is important to investigate alternative frameworks under which mandatory obligations to mitigate this potential planetary boundary threat may be 61 Connecting SDG 14 with the other SDGs through marine spatial planning Once and future 63 Once and future 64 Ocean plastisc 65 Art 194 plastics at sea 66 Art 207 (1) 67 Plastics at sea 68 Advancing international regulation of plastic pollution, 236 69 Towards an improved international framework 62 implemented.70 Plastic pollution is now considered a geological marker of the Anthropocene.71 To achieve the SDGs, notably SDG 14, by the 2030 objective a multilateral agreement must be reached to define the precautionary boundaries for the anthropocentric perturbations to demarcate a ‘safe operating space’ for humanity.72 As above, it is necessary to have regard to the function of existing international instruments. The Stockholm Convention on … functions to … through the elimination of (POP). With a focus on the manufacture, hazardous potential of plastic products is reduced as restrictions are placed upon the use of certain POPs during this phase.73 This is assisted by regulating the importation and exportation of these POPs for use in plastics,74 and that of waste containing these contaminants.75 The ambit, however, fails to go beyond plastic products containing the listed POPs. The Basel Convention on … was implemented to require the environmentally sound management of hazardous and other wastes. Generally, States are required to reduce generation of plastic waste to a minimum,76 and to refrain from transnational trade in hazardous waste or waste dealt with in non-environmental manner.77 (how does this specifically relate to plastic?). Limitations to the Basel Convention lie in the lack of compliance requirements and indicators, timelines or reduction reporting, precluding assessment of waste reduction progress.78 Thus in co-operation with the Stockholm Convention, the Basel Convention may address the life-cycle of plastics,79 the application is insufficiently comprehensive to provide the ecumenical, reduction framework necessary. The new proposition is an entirely new ‘global plastics treaty’ containing feasible measure that are verifiable and adequate to address the ubiquitous issue of plastic pollution.80 The scope of prevention on plastic pollution must address the production and consumption of plastics, achieving SDG 12, to regulate a global use reduction as an upstream approach will 70 Toward MPP 72 Advancing; MPP 73 B and S 74 Stockholm art 3.2 75 Art 6.d 76 Basel art 4.2 77 Art 4.1 -4.2 78 B and S 79 B and S 80 Plastics at sea; advancing; UNEA-1 71 be more cost-effective than mitigation downstream.81 Greater consistency and transparency between the regional and global sectors could be achieved through reporting, similarly, on the use of chemicals across the life span of plastics.82 Support for industry involvement is common,83 an increase in a multi-layered governance approach for co-operation between governments and corporations would benefit both sectors by conferring self-regulation of environmental and social criteria.84 A secondary objective of ameliorating domestic plastic waste treatment under this treaty could coincide with the Basel Convention waste management to reduce overall generation.85 Plastic pollution threatens to cause insurmountable environmental degradation should no action be taken, as the global ecosystem effects (especially of microplastics) is not well understood, a precautionary approach is necessary. Therefore, the new treaty could mirror, or at least take inspiration from the Montreal Protocol on Ozone Depleting Substances which effectively implemented a global reduction in chlorofluorocarbons in the atmosphere. Little consideration was given to this ‘new treaty’ during the 2019 United Nations Environment Assembly…? Conclusion International environmental instruments are integral in broadening the Agenda for 2030 as treaty objectives and obligations can be directly, and indirectly, linked to the SDGs and target indicators. Under the Paris Agreement, the NDCs can specifically refer to the SDGs, and persistence of REDD+ agreements will ensure that efforts against deforestation are enhanced. The Intergovernmental Conference on BBNJ, provides an opportunity to introduce mandatory reporting on marine activities, and benefit sharing schemes. Whilst the negotiations also touched upon the issue of marine plastic pollution interventions, this transboundary problem would be better dealt with under a new global plastics treaty which could provide universally improved environmental impacts. The current global Covid-19 pandemic places us at a crossroads: poverty and food scarcity are theorised to be corollary effects,86 this must be a ‘wake-up call for international cooperation and solidarity’ to increase sustainability efforts and these instruments pose pathways for this implementation. 81 Advancing Towards 83 Advancing (look at UNEP ref 122); towards 84 Towards 85 B and S 82 86 BIBLIOGRAPHY A. Articles Carlini, Giulia, and Kleine, Konstantin, ‘Advancing the international regulation of plastic pollution beyond the UN Environment Assembly resolution on marine litter and microplastics’ (2018) 27 (3) Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law 234 Gomez-Echeverri, Luis, ‘Climate and development: enhancing impact through stronger linkages in the implementation of the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)’ (2018) Philosophical Transactions A 376 Haward, Marcus, ‘Plastic pollution of the world’s seas and oceans as a contemporary challenge in ocean governance’ (2018) 9 Natur Communications 667 Kotzé, Louis J. and French, Duncan, ‘The Anthropocentric ontology of international environmental law and sustainable development goals: towards an ecocentric rule of law in the Anthropocene’ (2018) 7 Global Journal of Comparative Law 5 Pavoni, Riccardo, and Piselli, Dario, ‘The Sustainable development goals and international environmental law: normative value and changes for implementation’ (2016) 13 (26) Veredas do Direito 13 Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, opened for signature 22 April 2016 (entered into force 4 November 2016) United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, ‘Agenda 21’ (23 April 1992) United Nations, ‘Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ UN Doc A/RES/70/1 (25 September 2015)