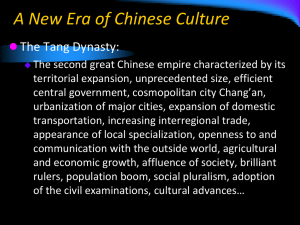

Nguyen 1 David Nguyen Mr. DeLucia Chinese Religion & Philosophy March 19, 2020 The proliferation of Taoism under the Tang Dynasty Taoism, a philosophical and religious Chinese tradition that emphasizes on living in accordance and harmony with the universe’s celestial structural order and natural flow, stems from the book of the Tao Te Ching and is said to be founded by Laozi, the supposed author of the aforementioned text. Taoism had had a profound influence on Chinese culture and religion ever since its first rise to popularity as traditional Chinese medicine, various martial arts, Chan Buddhism, and even Chinese astrology had intertwined with Taoism throughout Ancient China’s history. However, it wasn’t until China’s reunification under the Tang that Taoism experienced spectacular success or its “golden age.” Succeeding the tragic fall of the Sui Dynasty, the newly established Tang Dynasty placed exceptional significance and great values on Taoism as the tradition experienced unparalleled prosperity. The first Emperor of the dynasty, Li Yuan, claimed to be a descendent of Laozi, and as his influence grew, even the powerful Maoshan Taoists acknowledged him as the long-awaited fulfillment of messianic prophecy.1 Under the patronage of the Tang emperors, Taoism flourished as countless Taoist temples and schools were built to support the widespread diffusion of the tradition throughout the vast Tang empire. This development was further consolidated during the Ti’en Pao era when Emperor Xuanzong (reigned 712 – 756 CE) decreed it a state religion. Not only did Xuanzong come up with major innovative policies towards the religion that helped enhance the prestige of the imperial house but he also 1 Anna Seidel and Michel Strickmann, “Daoism under the Tang, Song, and Later Dynasties,” (Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc.). Nguyen 2 paid attention to and inaugurated an important ritual that extended Taoist implications throughout Mainland China: the worship of Laozi at the Palace of Great Clarity (Taiquing gong).2 After the establishment, reunification, and stability of the vast Tang Empire, Taoism has always been closely related to the Tang Dynasty in many aspects, ranging from societal and governmental to cultural elements. Socially, Taoists held relatively high and revered position. While Emperor Taizong issued an edict of 637 that favored the status of Taoists over Buddhist monks and nuns, Emperor Gaozong declared that Taoist priests belonged to the prestigious Zongzheng Temple and that their class was only lower than that of the kings. 3 As a result of Taoism’s influence, Tang Dynasty’s religious policies gradually grew into a full range of theocracy. Additionally, Taoism also became the foundational backbone of the Tang Dynasty’s state-run art as Emperor Gaozong became the first to rule the country completely by Taoism and the Taoist concept of wuwei was modified and extended to the governance of state relations. Culturally, Emperor Taizong’s deep-rooted respect for Taoism led a prosperous period of Tang literature that was predominantly influenced by Taoist ideas and notions: According to the "Mao Xian Weng's Biography", in the middle and late Tang government, senior Confucian civil servants and literati doctors such as Yuan Zhen, Bai Juyi, Han Yu, etc., loved Dai 道士毛仙翁, like a master or brother. "Either the teacher will serve it, or the brother will do it." They are all attached to Taoism. They may have different political opinions, but their love of Taoism is the same. 2 Victor Xiong, Ritual Innovations and Taoism under Tang Xuanzong, (T'oung Pao, Second Series, 82, no. 4/5, 1996), 258-316. 3 “Emphasizing Taoism and Restraining Buddhism: From the Belief of the Rulers in the Tang Dynasty to See the Influence of Taoism on the Society and Literature of the Tang Dynasty.” DayDayNews (blog), January 6, 2020. https://daydaynews.cc/en/history/301463.html. Nguyen 3 According to the "Compilation of Epitaphs of the Tang Dynasty", a large number of epitaphs and tombstones have Taoist thoughts.4 Taoism continued to be revered and obtained significant impact on not only the government and the Emperor but also the other classes in society throughout the boundless Tang empire but it wasn’t until the Tien’pao period that the religion reached its unprecedented peak with the unconditional support from Emperor Xuanzong. Much support for the Taoist church preceding the Tien’pao time period seems to have remained secondary to Xuanzong’s major developments in policy towards Taoism, all of which were intended to reinforce the imperial house’s prestige.5 He established a Taoist-based – rather than Confucian-based – system of education and qualification for civil service entry, which was ostensibly meant to adjoin into the governmental bureaucracy a group of men preferences were more closely aligned with those of the Tang rulers than was often the case with officials whose Confucian ideals could drive them into corruption, conflict, and betrayal. Under Tang Xuanzong’s instructions, the Examination on Taoism was established. Simultaneously, Chongxuan xue, or School for the Veneration of the Mystery, was founded in both of his capitals – Chang’an and Luoyang – and shortly after, similar schools with the same title was instituted in the 331 prefectures of the Tang Empire.6 The curriculum was based on Wenzi, Zhuangzi, Liezi, and Tao Te Ching, 4 “Emphasizing Taoism and Restraining Buddhism: From the Belief of the Rulers in the Tang Dynasty to See the Influence of Taoism on the Society and Literature of the Tang Dynasty.” DayDayNews (blog), January 6, 2020. https://daydaynews.cc/en/history/301463.html. 5 Timothy Barrett, Taoism under the T’ang: Religion & Empire during the Golden Age of Chinese History, (London: Floating World, 2006), 61-62. 6 Fabrizio Pregadio, The Encyclopedia of Taoism: A-Z, (London & New York: Routledge, 2008), 165. Nguyen 4 among other texts. Upon graduating from these schools, candidates would then go on to compete in the examination on Taoism the following spring. In order to sustain this new educational system, Emperor Xuanzong granted further advantages to recruit men of Taoist learnings in his decree of 748. He authorized those with knowledge of the four Taoist classics to recommended themselves, that is they could apply directly to prefectural governors for permission to sit for the examination. Candidates for other civil service examinations had to obtain a recommenda- tion from local notables in their districts before they could apply. Xuanzong also reduced the number of questions that graduates of the Examination on Taoism had to answer on the Placement Examination (xuan 選). The Place- ment Examination was the final ordeal that graduates of all examinations had to undergo before they received appointments to office. It evaluated the candidates’ character, eloquence, calligraphy, and judgment.7 The emperor evidently hoped that in doing so, Taoist studies would become the favored path for men pursuing positions of power. Xuanzong’s revitalization of the educational system had also rejuvenated the governing positions with the majority of prefectural governors being men of Taoist learning. This allowed the different states in the Tang Dynasty to be united under one religious and philosophical ideas, ensuring social and political stability for the Empire and further consolidating the far-reaching reverberations of Taoism on China during this time period. More importantly, Xuanzong instituted the coordinated worship of Laozi, the noble and stately ancestor of the religion, which was intended to emphasize the imperial line’s spiritual heritage and its continuing patronage from supernatural forces. According to an edict of 740, Laozi revealed himself in one of Xuanzong’s dreams and instructed the Emperor to look for his statue west of Chang’an and hold grand celebration ceremonies at the Xingqing Palace, Xuanzong’s predynastic residence. Upon locating the portrait, he set up the Datong Hall – one of the main halls at the Xingqing Palace – for worship and ceremonies, thereby showing his utmost respect for Laozi. 7 Fabrizio Pregadio, The Encyclopedia of Taoism: A-Z, (London & New York: Routledge, 2008), 166. Nguyen 5 This was the first recorded official effort to codify Laozi worship, which would later become the Taiqing Palace ritual.8 In the following year of 742, a petty official named Tien Wen-hsiu reported that Laozi had appeared to him in the street and announced to him the location of a talisman of Sacred Jewels, which Emperor Xuanzong then told him to retrieve. Tien’s successful attempt and the emergence of Emperor Xuanyuan (i.e. Laozi) persuaded Xuanzong to change the name of the era to T’ien Pao, Heavenly Treasure. The talisman itself was installed in a newly built modern temple of Emperor Xuanzong, which was now only one of a national network of such temples thanks to the inventions of 741. In the ninth month this temple and its companions in the eastern capital and elsewhere received the more exalted title T'ai-shang Xuanzong huang -ti kung. In 743 the titles were again changed: the temple in Ch'ang-an was named the T'aich'ing kung, that in Loyang the T'ai-wei kung, and those in the provinces Tzu-chi kung.9 These changes in names marked Xuanzong’s major development of a system of rituals for the worship of Laozi, demonstrating his favoritism toward Taoism and the influence and significance of the religion on China at the time. In general, various Tang Emperors paid their utmost respect to Taoism and saw the religion’s notions as the fundamental idea for governing the country. Principally, Emperor Xuanzong played a major role in the rising importance of Taoism during this time period for he not only incorporated Taoist morals into the education system but also initiated, revitalized, and extended the worship of Laozi and other major Taoist figures. On the whole, Taoism played a 8 Victor Xiong, Ritual Innovations and Taoism under Tnang Xuanzong, (T'oung Pao, Second Series, 82, no. 4/5, 1996), 264. 9 Timothy Barrett, Taoism under the T’ang: Religion & Empire during the Golden Age of Chinese History, (London: Floating World, 2006), 63. Nguyen 6 significant role in the political and social stability of the Tang Dynasty. Despite certain setbacks during the waning years of the Tang, Taoism recovered, continued to grow even after the Tang period, and reached its pinnacle in prominence during the reign of Emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty (1100-1125 CE).10 His reign would later be recognized by many historians and scholars as the heyday of Taoism in China. 10 Zhaoyang Zhang, Taoism in the Tang and Song dynasties, (Asian Art Museum, Khan Academy). Nguyen 7 Bibliography Barrett, Timothy. Taoism under the T'ang: Religion & Empire during the Golden Age of Chinese History. London: Floating World, 2006. Pregadio, Fabrizio, ed. The Encyclopedia of Taoism: A-Z. London & New York: Routledge, 2008. Seidel, Anna, and Michel Strickmann. “Daoism under the Tang, Song, and Later Dynasties.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Daoism/Daoism-under-the-Tang-Song-and-laterdynasties. Xiong, Victor. "Ritual Innovations and Taoism under Tang Xuanzong." T'oung Pao, Second Series, 82, no. 4/5 (1996): 258-316. Accessed March 16, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4528700. Zhang, Zhaoyang. “Taoism in the Tang and Song dynasties.” Asian Art Museum, Khan Academy. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-asia/imperial-china/tangdynasty/a/taoism-in-the-tang-and-songdynasties#:~:text=During%20the%20Tang%20Dynasty%20(618,supported%20th e%20development%20of%20Taoism.&text=Under%20the%20patronage%20of% 20the%20emperors%2C%20Taoism%20flourished%20in%20the%20Tang. “Emphasizing Taoism and Restraining Buddhism: From the Belief of the Rulers in the Tang Dynasty to See the Influence of Taoism on the Society and Literature of the Tang Dynasty.” DayDayNews (blog), https://daydaynews.cc/en/history/301463.html. January 6, 2020. Nguyen 8