Locke’s Essay - Book II - Chapter 27 - Of Identity and Diversity

advertisement

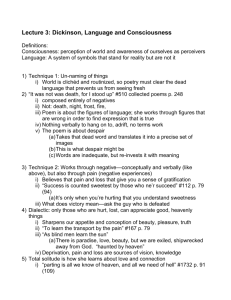

Locke’s Essay, Book II, Chapter 27: “Of Identity and Diversity” §1. Wherein identity consists In this section Locke is distinguishing two different kinds of identity: 1: Numerical identity (Fred is identical with himself) 2: Exact resemblance (Fred is identical to his twin brother Ned) He is concerned only with the former, about which he makes two claims: a) At one and the same location at one and the same time, there cannot exist two different entities of the same kind. b) If two things began in two different space-time location, they are not numerically identical. §2. Identity of substances We have notions of three different kinds of substances, to which different identity conditions are appropriate: Substance Identity conditions God Omnipresent, unchanging, eternal Finite intelligences (e.g., humans) Individuated according to their beginning locations in space and time (unlike Descartes, Locke believes minds have locations) Bodies (i.e., material objects) One and only one particle of matter can exist at a particular location in space and time. Now, each of these types of substances excludes other substances of the same type from existing at that same place and time (which means, effectively, that there can only be one God), but you can have three different substances existing at the same location in space and time (e.g.: my mind, my body and God all exist right here right now). §3. Principium Individuationis Existence is the principle of identity: as long as an atom exists, it is the same atom. (This is identity through time.) This principle can be enlarged to cover collections of atoms. Thus, a “mass” is the same as long as it consists of exactly the same atoms (“let the parts be every so differently jumbled”), but if it loses or gains even one, it is a different mass (even though the atoms themselves will not lose identity, they will remain the same atoms). However, different identity conditions must apply to living things, because an acorn becomes an oak tree while changing drastically the matter it is composed of. §4. Identity of vegetables The principle of identity for plants is “partaking in one common life” – thus a plant can completely change the cells of which it is composed over time while remaining the same, so long as it is the “same life” that continues. (Question: what is that “same life”? Locke’s answer seems to involve function, as we shall see.) §5. Identity of animals Just as with plants, the identity of animals consists in partaking of the same life, but Locke illustrates this with an analogy with machines – I’m driving the same car I’ve had for a long time, even though it has new wheels, a new engine and a new radiator, because they the new bits take up established roles in a machine with an unchanging function. 1 §6. The identity of man The same principle applies for man, that is “in nothing but a participation of the same continued life, by constantly fleeting particles of matter, in succession vitally united (i.e., having the same life) to the same organized body”. This is the only condition that can make “an embryo, one of years (i.e., an old person), mad and sober, the same man” and avoid implying that “Seth, Ismael, Socrates, Pilate, St. Austin, and Caesar Borgia” are one and the same. This latter, Locke argues, is the effect of having same soul be the criterion of identity – for, for all we know, all those men listed had the same soul. (And matters are worse if you believe in transmigration – then you can throw Lassie and Mr. Ed in there.) §7. Idea of identity suited to the idea it is applied to We should not assume that the same identity conditions will work for different things. A lump of matter could be the same substance without that meaning that it is the same man, and something could be the same man without being the same person – there are three different conditions of identity (what it is to be the same X) for each of those three. (Locke has yet to give his identity conditions for person, for which he is most renowned, but has already made it clear that it is not enough to show that it is the same substance, whether physical or mental.) §8. Same man A common definition of “man” is “rational animal”, but Locke gives a story of an apparently rational parrot to illustrate that this definition is too broad (because, even if it were rational, the parrot is not a man). §9. Personal identity Definition of person: a thinking intelligent being, that has reason and reflection, and can consider itself as itself, the same thinking thing, in different times and places; which it does only by that consciousness which is inseparable from thinking, and, as it seems to me, essential to it The condition for identity through time is also established through consciousness: a far as this consciousness can be extended backwards to any past action or thought, so far reaches the identity of that person; it is the same self now it was then §10. Consciousness makes personal identity Same consciousness (and not same substance) means same person. Problem: our consciousness is interrupted (for example, in sleep) – does that mean we cease to exist when this happens? Answer: not as a substance, or as a human, but yes, as a person. For it is by the consciousness it has of its present thoughts and actions, that it is self to itself now, and so will be the same self, as far as the same consciousness can extend to actions past or to come. and would be by distance of time, or change of substance, no more two persons, than a man be two men by wearing other clothes to-day than he did yesterday, with a long or a short sleep between: the same consciousness uniting those distant actions into the same person, whatever substances contributed to their production. That is: personhood can be “gappy”, and the same person can exist within different substances… 2 §11. Personal identity in change of substance …which fits with what we believe about matter, because humans supposedly replace all the cells in their body every seven years, and, as Locke points out, although my hand is part of me, cut it off, so that I am no longer conscious of it, and “it is then no longer part of that which is [my]self, any more than the remotest part of matter”. Thus consciousness is not just the criterion of identity through time, but also in space – what I am right now includes all that I can feel. (BUT: I can’t feel my liver – does that mean it’s not part of me?) §12. Personality in change of substance Materialists must think this possible, because they know the same person can change that matter of which she is made but be the same person. What about people like Descartes, who claim that each of us is a mind, or immaterial substance? §13. Whether in change of thinking substances there can be one person if the same consciousness … can be transferred from one thinking substance to another, it will be possible that two thinking substances may make but one person. For the same consciousness being preserved, whether in the same or different substances, the personal identity is preserved. That is, if a soul or mind is like a hard drive, which is blank when we’re born but acquires information as we grow, then, if the information on the hard drive (our memories) is transferred to another hard drive (a different mind/soul) then the person goes with the memories, and you have a case of the same person having two different minds or souls at different times. Thus, same soul is not necessary for same person. §14. Whether, the same immaterial substance remaining, there can be two persons Is same soul sufficient for same person? Locke considers the views of Christian Platonists or Pythagoreans, who believe that the same soul can be recycled. He tells of one such who claimed to have the soul that Socrates used. Locke asks, suppose this is true: does that mean that that man is (the same person as) Socrates? Locke thinks it is self evident that he is not, which means that same soul is not sufficient for same person either. §15. The body, as well as the soul, goes to the making of a man While same consciousness makes same person, you need to have the same body to be the same man. Thus, if I were to switch bodies with LeBron James, I would be the same person I used to be (only with a younger, taller, more athletic body) but not the same man (Locke’s example is with a prince and a cobbler). This illustrates again that man and person have different identity conditions. §16. Consciousness alone unites actions into the same person whatever has the consciousness of present and past actions, is the same person to whom they both belong. Had I the same consciousness that I saw the ark and Noah's flood, as that I saw an overflowing of the Thames last winter, or as that I write now, I could no more doubt that I who write this now, that saw the Thames overflowed last winter, and that viewed the flood at the general deluge, was the same self,--place that self in what substance you please--than that I who write this am the same myself now whilst I write (whether I consist of all the same substance, material or immaterial, or no) that I was yesterday. That is: I think I am the same person as I was yesterday because I who am aware of myself now also remembers being me yesterday. For exactly the same reason, if I could remember Noah’s flood, then that was me experiencing it, even if I had to get a new 3 body to live this long. And if I remember being Cain killing Abel, then I am responsible for that, and can be held accountable. §17. Self depends on consciousness, not on substance As in §11, sameness of consciousness provides the criteria for what all (in space) comprises me now, as for identity across time. Thus every one finds that, whilst comprehended under that consciousness, the little finger is as much a part of himself as what is most so. Upon separation of this little finger, should this consciousness go along with the little finger, and leave the rest of the body, it is evident the little finger would be the person, the same person; and self then would have nothing to do with the rest of the body. §18. Persons, not substances, the objects of reward and punishment To continue the “little finger” thought experiment: if all my consciousness goes into my little finger when it is separated, then, even if the rest of my body remains alive, with a new consciousness, it is the little finger that is responsible for all my past deeds, not the rest of the body. §19. Which shows wherein personal identity consists if Socrates and the present mayor of Queinborough agree, they are the same person: if the same Socrates waking and sleeping do not partake of the same consciousness, Socrates waking and sleeping is not the same person. And to punish Socrates waking for what sleeping Socrates thought, and waking Socrates was never conscious of, would be no more of right, than to punish one twin for what his brother-twin did, whereof he knew nothing, because their outsides were so like, that they could not be distinguished; for such twins have been seen. §20. Absolute oblivion separates what is thus forgotten from the person, but not from the man Locke considers total amnesia as a legal excuse: Suppose I wholly lose the memory of some parts of my life, beyond a possibility of retrieving them, so that perhaps I shall never be conscious of them again; yet am I not the same person that did those actions, had those thoughts that I once was conscious of, though I have now forgot them? His answer: I am the same man, but not the same person, and it is person that matters for reward or punishment (see §18), so amnesia is an excuse. So is split personality: But if it be possible for the same man to have distinct incommunicable consciousness at different times, it is past doubt the same man would at different times make different persons; which, we see, is the sense of mankind in the solemnest declaration of their opinions, human laws not punishing the mad man for the sober man's actions, nor the sober man for what the mad man did,- thereby making them two persons: which is somewhat explained by our way of speaking in English when we say such an one is "not himself," or is "beside himself" So Jekyll is not responsible for what Hyde did. They are the same man, but different persons. §21. Difference between identity of man and of person Can the same man (Socrates) really be two different persons (asleep and awake)? Yes. We just have to keep clear what the identity conditions are for man (same body and soul) and for person (same consciousness) and note that they don’t always coincide. To which does the name “Socrates” refer? It depends on who’s speaking and the context (but usually man). 4 §22. But is not a man drunk and sober the same person? No, he isn’t, if when sober he cannot remember what he did when drunk. (Problem: what if, when drunk, he can remember what he did when sober, but not vice versa? This would be a variant of Thomas Reid’s famous General paradox: an old general remembers being a young private, and the young private remembers being a boy, but the general doesn’t remember being the boy. Is the general the same person as the boy?) Should we punish the sober man? We do, but really we shouldn’t. God will know the truth on the day of judgment, though. (Question: on the day of judgment, who gets to keep the body – the drunk man or the sober man?) §23. Consciousness alone unites remote existences into one person More arguments against the Cartesian personal identity criterion of the soul: granting that the thinking substance in man must be necessarily supposed immaterial, it is evident that immaterial thinking thing may sometimes part with its past consciousness, and be restored to it again: as appears in the forgetfulness men often have of their past actions; and the mind many times recovers the memory of a past consciousness, which it had lost for twenty years together. Make these intervals of memory and forgetfulness to take their turns regularly by day and night, and you have two persons with the same immaterial spirit, as much as in the former instance two persons with the same body. So that self is not determined by identity or diversity of substance, which it cannot be sure of, but only by identity of consciousness. That is, you have an instance of the same soul having two different persons within it. Thus, once again, same soul is not sufficient for same person. §24. Not the substance with which the consciousness may be united Just as a hand, once part of me, is no longer when I cannot feel it any more (because it’s been cut off), so we can imagine the same for a chunk of immaterial substance: In like manner it will be in reference to any immaterial substance, which is void of that consciousness whereby I am myself to myself: if there be any part of its existence which I cannot upon recollection join with that present consciousness whereby I am now myself, it is, in that part of its existence, no more myself than any other immaterial being. For, whatsoever any substance has thought or done, which I cannot recollect, and by my consciousness make my own thought and action, it will no more belong to me, whether a part of me thought or did it, than if it had been thought or done by any other immaterial being anywhere existing. §25. Consciousness unites substances, material or spiritual, with the same personality For both material and immaterial substances, chunks can start by being part of me, cease to be part of me (when I’m no longer conscious of them) and even become part of somebody else (say, if atoms that were part of my finger are later on part of some new human’s finger, or, if Socrates’s soul goes on to be used by the contemporary Christian Platonist). §26. “Person” a forensic term You should be punished and rewarded for what you did as a person, not as a man. §27. Suppositions that look strange are pardonable in our ignorance It might be the case that consciousness could never be separated from soul or body, in which case the same man would always be the same body, and vice versa. BUT, given 5 our state of ignorance, we can distinguish them, and thus can justifiably imagine cases of two different persons in the same man or two different men being the same person. §28. The difficulty from ill use of names Confusion only arises if we are not clear what we mean by “man” or “person” or “Socrates.” Hence the importance of spelling out identity conditions for each. §29. Continuance of that which we have made to be our complex idea of man makes the same man The identity conditions of “man” depend on the definition of man. That is, if a man is “a rational spirit” – then the same man is the same rational spirit (duh). 6