The Romantics and Their Descendents and the Facets of Isolation (1)

advertisement

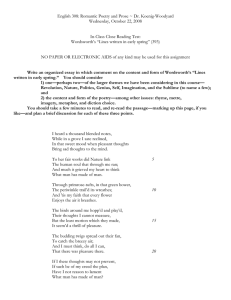

The Romantics and Their Descendents and the Facets of Isolation The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word isolation as, "The action of isolating; the fact or condition of being isolated or standing alone; separation from other things or persons; solitariness.” The Cambridge Dictionary provides the following as its first definition, “the condition of being alone, especially when this makes you feel unhappy.” The Merriam Webster dictionary claims that the etymological root of the word developed from the Latin word for island. Keeping all of this in mind, it becomes clear that the word “isolation” has various meanings and connotations. Given the nature of poetry and the spectrum of meaning that it spawns, a single word such as isolation can result in a variety of interpretations. The intent of a poet as well as the context which an audience provides can lead to a multiplicity of meaning. By studying the theme of isolation and its accompanying overtones in a handful of poems by William Wordsworth, Thomas Hopkins, and Toni Harrison, the richness of this single term can emerge. For many, the word, “isolation,” conjures thoughts relevant to the word’s most negative connotation. William Wordsworth, would likely not have been one of these people. Or rather, what many deem isolation, Wordsworth might have instead considered “solitude.” The act of separating oneself from people and society was a noble venture in his mind, a necessary step towards achieving a higher state of being. For only when in solitude or isolation, can one truly pause and reflect on the deeper meaning of life. As is evident in his poetry, as well as his autobiographical work, The Prelude, Wordsworth himself was in a constant state of self reflection. Throughout his poetry, Wordsworth constantly urges his readers to stop and take a moment to engage in this same kind of deep meditation. Perhaps most notably in, “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye during a Tour. July 13, 1798,” Wordsworth meditates on the transcendental powers of nature. He reflects on his surroundings upon revisiting a location in nature that he has not been to in five years. When he was younger his appreciation for Nature ran skin deep. He objectified her, allowing himself to become excited by her beauty with the flightiness of a child. But no longer, “For I have learned / To look on nature, not as in the hour / Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes / The still sad music of humanity,” he says, in the middle of stanza four. His appreciation has grown past its superficial roots. Now he sees the ways in which Nature aids in his spiritual growth. The forest and cliffs provide a hideaway, prompting, “Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect / The landscape with the quiet of the sky / The day is come when I again repose” (7-9). The peaceful solitude which Nature provides allows him to venture more deeply into the recesses of his mind. He speaks of a quiet pastoral scene and a lone hermit by the fire, casting such seemingly ordinary things and people in a light of humble nobility. Towards the middle of the fourth stanza, Wordsworth writes, “—And I have felt / A presence / that disturbs me with the joy / Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime / Of something far more deeply interfused.” While he used to marvel at the beauty of his current surroundings, he gleans something far deeper from them now. His time alone in nature provokes his soul and mind, providing him with insight into the human condition. The power of this newfound awakening is one so strong that it allows him to travel through time as he reflects on past, present and future versions of himself. Wordsworth’s admiration and appreciation for the state of solitude is also clearly exhibited in his poem, “Michael.” “Michael” tells the story of a shepherd, his son Luke, and their efforts to save the land of their forefathers. The poem opens with the lines, “If from the public way you turn your steps / Up the tumultuous brook of Green-head Gill,” (1-2). Right from the beginning, Wordsworth is asking his readers to retreat from the man-made world in which they live to be alone in the countryside described in the poem. While he recognizes the climb is arduous and leads to a scary unknown, “The mountains have all open'd out themselves, / And made a hidden valley of their own,” he says (7-8). Though shedding old ideologies is indeed frightening, succumbing to the transcendental powers of nature will allow one to reach a new level of consciousness that is incomparable to the old, making the climb well worth it. Leave the city, come to the countryside and discover the truest version of yourself. Wordsworth believed that civilization was the place in which we are most discontent, that the social world is a corrupt and inhibiting one. It is perhaps unsurprising then that Wordsworth was initially an active supporter of the French Revolution. After all, freedom from the oppression of an unjust government is not entirely unlike freedom from the oppressive ideologies of one’s mind. In fact, they are arguably one in the same. He believed that the first step to freeing oneself was time alone in Nature. In the opening of the poem “Michael,” Wordsworth describes a pastoral scene, designating it “an utter solitude” (13). He is telling his readers that they must be alone in order to reach a contemplative state, and that Truth comes from time alone with nothing. While many of his contemporaries may have put more emphasis on the sophisticated lifestyle and language of the social elite, Wordsworth (as initially set forth in his first 1798 collection, Lyrical Ballads) shifted the focus to common folk and ordinary language. It was his belief that lower class people not only had the same passions as rich people, but that those passions were in fact truer and purer. In “Michael,” the narrator rejects the trappings of city life. This kind of frivolous immoral state of being is what ultimately leads to the demise of the wholesome way of life Michael intended for his son and their posterity. The hardships Michael has encountered throughout his life in Nature, simple as they may seem, have formed him into a noble and respectable man—one who is not only deeply in touch with himself, but with the world at large. Here lies the paradox; it is our time spent alone that ultimately allows us to connect most deeply with others. In the poem, the sensibility which accompanies the solitary life of the shepherd Michael, is lost to his son when Luke goes on to live a life in the city. As result of his move, Luke's value system is clouded by the moral pollution of a life detached from Nature. Luke, quite sadly, goes on to fail his family and live a life of ignominy. Though his son has broken his heart, Michael continues on with his work as a servant of Nature. Upon his death, his memory lives on in the lands which he so dutifully worked all throughout his life. Ultimately, through the stories of Michael and Luke, Wordsworth argues that experiences in isolation are what unlock new levels of feeling and understanding which are necessary to connect most meaningfully with the world. Gerard Manley Hopkins would likely have agreed with Wordsworth that reflection is necessary for living a life full of meaning, however, the poetic means by which Hopkins arrives at such a conclusion is far less appealing. Being that Hopkins was a Catholic priest and that much of his work was published posthumously at the turn of the century, his poetry bears the burden of grappling with the many scientific discoveries that arose around this time such as the development of Darwinism as well as new geological findings. This coupled with heightened urbanization and the effects of laissez faire economics on England, led many to question the central importance of religion in their lives against the backdrop of science and capitalism. Yet for others, the natural existentialist dread which resulted from such developments led to a revival of religion in the face of such cosmic disruption. Like any artist or writer would, Hopkins turned to his poetry for catharsis. Poetry served as a vehicle for his philosophical ponderings, his grapplings with his faith and feelings of utter despair. Hopkins was not one to shy away from what some would consider highly provocative questions for a Catholic priest. Be it the meaning of life or mankind’s role in the world, Hopkins used poetry to help bring him a sense of clarity. Hopkins’s poem, “No Worst There is None. Pitched Past Pitch of Grief.” provides us a glimpse into the inner workings of his depressed mind as he candidly questions his faith in a solitary act of reflection. While Wordsworth may have acknowledged the struggles of being alone in the wilderness, his work, nonetheless, captures images of tranquility, stoicism, and peace. The theme of isolation sings a different tune in much of Hopkins’s work, including “No Worst There is None. Pitched Past Pitch of Grief.” The opening line begins, “No worst, there is none. Pitched past pitch of grief” (1). There is no limit to how terrible things are, just when he thinks the worst is behind him, worse things happen still. He is thrown past the point of whatever grief may sound like, into a pit of utter despair. The alliteration and assonance found in this line and others throughout the rest of the poem echo the unpleasant and downright distasteful things of which he speaks. Already, the reader can see that Hopkins feels utterly isolated. The depression he is experiencing has caused him to close off from the world, a prisoner to his tortured mind. “Comforter, where, where is your comforting?” he asks in the third line of the poem. This particular line is striking considering that Hopkins was a Catholic priest. This despair itself is a cardinal sin in his doubting of God’s power to bring him salvation, in his lack of faith that God will make things better. The line could easily be considered an act of blasphemy. Who is he to question God, creator of all things? And yet he does, and continues to do so. This is testament to the depths of his desperation. Alone, with nothing but his thoughts and his words, he struggles to find peace. And yet he lacks agency. “Then lull, then leave off. Fury had shrieked 'No ling- / ering! Let me be fell: force I must be brief"' he says (7-8). Throughout this poem Hopkins is the helpless object of the universe; things are being done to him. Utterly powerless, he can do little to nothing to help himself. By the time we reach the second stanza, Hopkins has moved to reflecting on the nature of his mind. Paradoxically, he uses the external metaphor of mountains to describe his inner state of being, “O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall” (9). While in Wordsworth, the mountains act as a solid stabilizing force, a physical backdrop for peaceful contemplation, here, the mountains symbolize the danger of the mind. They are not something to be climbed and conquered, rather, the mountains of his mind are treacherous and hold the potential to conquer him instead. Hopkins speaks of sleep and death as being one in the same. He abandons all the consolations his faith ought to give him, essentially refusing God and the belief in an afterlife. And yet in other poems by Hopkins such as, “Carrion Comfort,” we see this act of solitary reflection lead to more fruitful conclusions. While the poem opens with a similar sense of sadness, Hopkins instead now rejects despair, “Despair, not feast on thee” rather than succumbing to it (1). While he mentions his thoughts of suicide, “not choose not to be,” he ultimately decides to press forward (4). Still, Hopkins engages in what some would consider a blasphemous questioning of God, “But ah, but O thou terrible, why wouldst thou rude on me,” (5). Why does God make him suffer, why does He cause him pain? Why does He seem to revel in it, a suffering that ultimately causes Hopkins to run further and further away from Him? Yet, Hopkins is careful not to slip into the despair that so characterizes “No Worst There is None. Pitched Past Pitch of Grief.” In the second stanza, Hopkins finds sweet salvation. He begins to realize that upon accepting the pain and suffering, he finds peace. In kissing the hand which doles out his suffering, he has come to see that this suffering is meant to strengthen and fortify him. This provides him with a sanguine resurgence of hope that gives him the strength to carry on. He attributes this realization to his willingness to pose such tough questions to God. “Cheer whom though? The hero whose heaven-handling flung me, foot trod / Me? or me that fought him? O which one? is it each one? That night, that year / Of now done darkness I wretch lay wrestling with (my God!) my God” (12-14). God will push you to be better, but only if you push Him first. It is only by demanding an answer of Him that you shall get it. Hopkins is therefore advocating for the necessity of intensely reflecting on one’s faith and existence, a process that can only be undertaken in isolation. Only then is one’s faith real. Only when alone and pushed to one’s limits will one truly understand that there is meaning in the struggle that is life. But isolation is not always physical, and it certainly is not always self-imposed. As an erudite poet with a degree in Classics, with roots in a working-class home in the industrial city of Leeds, Toni Harrison has experienced a different kind of isolation throughout his life. Harrison has experienced isolation in the form of alienation—alienation from family and friends due to his education, and alienation in the world of academia due to his humble origins. Ironically, even when in a room full of scholars, or when surrounded by family in his childhood home, the language of his mind and the language which he speaks, has distanced him from some people nearly as much as it has connected him to others. In Harrison’s poem, “Them and [uz],” these two conflicting worlds confront each other right away. The poem begins with a clever wordplay, “αίαι, ay, ay! … stutterer Demosthenes / gob full of pebbles outshouting seas –” (1-2). Though the phrases sound the same, the Greek signals the beginning of a serious speech, whereas the English simply means “yes” and might be used to get a crowd excited. Much like the term isolation, Harrison is pointing out the multiple meanings that can be drawn from the same sounds, and the implications of different sounds for the same word. “4 words only of mi ‘art aches and … ‘Mine’s broken, / you barbarian, T.W.!’ He was nicely spoken. / ‘Can’t have our glorious heritage done to death!’” says Harrison as he recounts being chastised by his teacher for his accent when reading Keats in class (3-5). A few lines later Harrison challenges this notion by reminding his readers that Keats himself may have had a Cockney accent. Is good poetry truly only reserved for those who speak a certain way? Is good poetry truly only for the upper class? Again, Harrison is reprimanded for his speech in line 13, “‘We say [Λs] not [uz], T.W.!’ That shut my trap.” Yet the way Harrison writes “[Λs]” and “[uz]” in the poem exposes the sheer arbitrariness of the supposed superiority of one phonetic pronunciation over the other. Both words are bracketed and they both require international phonetic notation; there is no difference between them. Whatever difference that exists is contrived and loaded by one’s class, education, and upbringing. Ultimately, Harrison overcomes the idea that the way he speaks is inherently wrong or less than, “and used my name and own voice: [uz] [uz] [uz], / ended sentences with by, with, from, / and spoke the language that I spoke at home. / RIP, RP, RIP T.W. / I’m Tony Harrison no longer you!” (22-26). He goes by Tony, so that’s the name he’ll use. He was raised saying [uz], so he’ll say it over and over again till he is blue in the face. He’ll end sentences with prepositions if he so pleases because that is the way he and his family speak. He will no longer try to conform and become someone who he is not. Instead, he will embrace his roots and the language that he knows, and cross the divide that academia has created for him and those of his class. His teacher once told him that he cannot speak English, so he went on to learn both Latin and French. Harrison will not let society’s restrictions keep him from greatness. And yet, despite the vigor and persistence with which he so defiantly writes, Harrison is a victim of his language still. The poem ends, “My first mention in the Times / automatically made Tony Anthony!” When moving in the academic sphere, his very identity has already been determined for him and without him; he is relegated to the more professional “Anthony” as opposed to the more casual nickname “Tony” that defines him in his actual day-to-day life. The same discord that results from Harrison’s two contradictory identities leads to a lack of understanding in his own home as well. Harrison’s poem, “Book Ends,” describes the aftermath of his mother’s death as he and his father struggle to arrive at an inscription for her gravestone. “We never could talk much, and now don't try,” says Harrison when describing him and his father (4). His mother served as something of a mediator between him and his father. While his father, (a baker) speaks the language of the working class, Harrison speaks the language of the academic, and without his mother there to translate, they seem to forget they are more alike than they are different. The only thing connecting them now is their silence. “For all the Scotch we drink, what's still between 's / not the thirty or so years, but books, books, books” Harrison elaborates on his mother’s extended metaphor of the father son pair being like bookends (15-16). It is not the age gap that keeps them from identifying with one another, but the disparity in education. Harrison’s degree has afforded him the benefits of upward social mobility. Not only does he think and speak differently now, he occupies an entirely different social rank. Ironically, the education which both his parents likely worked so hard to provide him, is ultimately what keeps them worlds apart. “You're supposed to be the bright boy at description / and you can't tell them what the fuck to put!” says his father (31-32). For all the words Harrison knows, for his depth of knowledge of French, Latin, and Greek—he struggles to find the words for his mother’s tombstone. While lacking in eloquence and brevity, his father, the inarticulate baker, ends up being the one to come up with the right words. “I've got the envelope that he'd been scrawling, / mis-spelt, mawkish, stylistically appalling / but I can't squeeze more love into their stone” (34-36). In this moment, Harrison realizes that however rough or clumsy the language, the meaning of his father’s words are as or more powerful than the words of any professional poet, because they are rooted in a raw sense of genuine love, loss, and longing. While him and his father may be at two opposite ends of the shelf, they are both books nonetheless. Yet despite this semi-heartwarming conclusion, the fact remains that there are still leagues of distance between father and son. No matter how hard they try, they will never be able to relate to one another with ease. The language that has evolved the manner in which Harrison thinks and speaks, opening all sorts of doors for him in the world of academia, allowing him access to new people and places, is ironically what keeps him from deeply connecting to the people closest to his heart. This paradox of language serves to alienate him in all walks of life. He, like Hopkins, is a prisoner of his own mind. Harrison is only ever understood by some, and never understood fully, not for all of the facets of his mind and being. Class and language keep Harrison isolated as he works against a tradition that has no place for him. Ultimately, through studying Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey” and “Michael,” Hopkins’s “No Worst There is None. Pitched Past Pitch of Grief.” and “Carrion Comfort,” as well as Tony Harrison’s “Them and [uz]” and “Book Ends,” with a particular focus on the theme of isolation, we begin to understand its complexity. One can find themselves in a state of tranquil solitude that enriches their understanding of self and the world. Or one may find themselves flung into a state of isolation of mind as they grapple with their faith and sense of purpose in the greater cosmic universe. On a smaller scale, but a consequential one nonetheless, one can also find themselves alienated by the sheer power of language and class. Isolation takes on many forms in the poetry of the Romantics and their descendents, challenging our conceptions of what isolation may mean to us in our present day. Works Cited “Book Ends - Poem by Tony Harrison.” Back to Main Page, fffffamouspoetsandpoems.com/poets/tony_harrison/poems/12690. Hopkins, Gerard Manley. “Carrion Comfort by Gerard Manley Hopkins.” Poetry Foundation, ffffPoetry Foundation, www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44392/carrion-comfort. Hopkins, Gerard Manley. “'No Worst, There Is None. Pitched Past Pitch of...” Poetry ffffFoundation, Poetry Foundation, ffffwww.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44398/no-worst-there-is-none-pitched-past-pitch-of-grief. Library. “Final Published Version of 'Them & [Uz]'.” Library, fffflibrary.leeds.ac.uk/special-collections/view/548. “William Wordsworth – Michael: A Pastoral Poem.” Genius, ffffgenius.com/William-wordsworth-michael-a-pastoral-poem-annotated. Wordsworth, William. “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey,...” Poetry ffffFoundation, Poetry Foundation, ffffwww.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45527/lines-composed-a-few-miles-above-tintern-abbey-of fffn-revisiting-the-banks-of-the-wye-during-a-tour-july-13-1798.