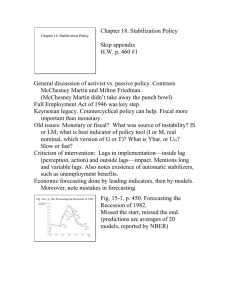

Chapter 24 THE CHICAGO SCHOOL—THE NEW CLASSICISM president of the American Economic Association in 1967, and won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1976. Friedman’s ideas are known to a wide spectrum of the American public. He served as a columnist for Newsweek, wrote popular books, participated in an educational television series, and delivered addresses to numerous groups. Consumption Function In 1957, Friedman published A Theory of the Consumption Function, in which he suggested that the Keynesian consumption function is too simplistic: Consider a large number of men all earning $100 a week and spending $100 a week on current consumption. Let them receive their pay once a week, the pay days being staggered, so that one-seventh are paid on Sunday, one-seventh on Monday, and so on. Suppose we collected budget data for a sample of these men for one day chosen at random, defined income as cash receipts on that day, and defined consumption as cash expenditures. One-seventh of the men would be recorded as having an income of $100, six-sevenths as having an income of zero. It may well be that the men would spend more on pay day than on other days but they would also make expendi- tures on other days, so we would record the one-seventh with an income of $100 as having positive savings, the other six-sevenths as having negative savings…. These results tell us nothing meaningful about consumption behavior; they simply reflect the use of inappropriate concepts of income and consumption. Men do not adapt their cash expenditures on consumption to their [short-term] cash receipts.4 Friedman pointed out that lengthening the period of observation from a day to a week would eliminate the error in this simple example. But in terms of actual consumption-income data, the use of a period of even one year fails to correct the problem. According to Friedman, a household’s consumption is determined by permanent income rather than current income, where permanent income is defined as the average income that people expect to receive over a period of years. People attempt to maintain a reasonably stable standard of living from one year to the next, and changes in income that are considered to be temporary or transitory will neither greatly increase nor decrease people’s present consumption. Stated differently, consumption does not respond to every change in income caused by changes in investment or government spending; it responds only to changes in income that people view to be permanent and long-lasting. The implication is that the marginal propensity to consume out of changes in current income is smaller than the Keynesian theory would suggest. This means that the investment multiplier is small, which in turn implies that the alleged internal instability in the economy is overstated.5 4 Milton Friedman, A Theory of the Consumption Function (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1957), 220. 5 In 1963, Albert Ando of the University of Pennsylvania and Franco Modigliani of MIT developed a similar theory in which consumption is related to income over people’s entire lifetime. Like Friedman’s hypothesis, this “lifecycle” theory implies that consumption in a given period may be less sensitive to changes in current income than some Keynesians suggested. Albert Ando and Franco Modigliani, “The ‘Life Cycle’ Hypothesis of Saving: Aggregate Implications and Tests,” American Economic Review 53 (March 1963): 55–84. Modigliani won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1985 for his work. Chapter 24 THE CHICAGO SCHOOL—THE NEW CLASSICISM Monetary Theory Friedman is best known for his ideas on the role of money in the economy. In this regard he discussed several interrelated topics, including the demand for money, the quantity theory of money, the causes of the Great Depression, the ineffectiveness of fiscal policy, the long-run vertical Phillips curve, and the “monetary rule.” The demand for money. Friedman viewed the demand for money as the demand for cash balances. People demand cash balances because they provide utility to the holder. Unlike Keynes, Friedman made no distinction between types of money, that is, between idle versus active balances or transaction versus speculative balances. There are three major determinants of the amount of money households and enterprises will desire to hold at any given time. These determinants are independent of factors that influence the supply of money. Total wealth. Total wealth in all forms, including human capital, can best be measured by permanent income. As wealth, or permanent income, increases, the amount of money people desire to hold as cash balances also increases. ● Cost of holding money. The second major determinant of money demand is the cost of holding money. Higher costs will result in less money being held. These costs vary with the interest rate, the expected rate of inflation, and the price level. One cost of holding money consists of the direct “interest rate” foregone on other forms of wealth that could be held. If the returns on nonmoney assets such as stocks and bonds rise, the opportunity cost of holding money rises, and less money is demanded. In general, however, the quantity of money demanded is insensitive to changes in the interest rate. The yield spread between returns on transaction (money) and nontransaction (stocks, bonds) forms of wealth is relatively stable. For example, when interest rates in general increase, banks compete to maintain their checkable accounts either by offering higher interest on these accounts or by increasing noncash benefits (quality of service, convenience, “no cost” safe deposit boxes). Consequently, the relative opportunity cost of holding money does not change significantly with changes in the interest rate in the economy, and the demand for money is interest inelastic. Another cost of holding money relates to the expected rate of inflation. This is the opportunity cost of foregone capital gains on real assets; it is the “return” sacrificed on assets that appreciate in value. Higher expected rates of inflation enhance the prospects for capital gains and thus increase this cost of holding money. Therefore, people reduce their present cash balances when they expect higher inflation. A final cost of holding money relates to the price level (as distinct from the expected rate of inflation). The higher the price level, the less the nominal cost of holding money because each dollar held will buy less. Increases in the price level, say, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, cause proportionate increases in the amount of money demanded. People will desire to increase their cash balances to keep them constant in real terms; that is, they will want to hold more cash to buy the higher-priced goods. ● 535 536 Chapter 24 THE CHICAGO SCHOOL—THE NEW CLASSICISM ● Preferences. Preferences, or basic attitudes, about holding and using cash are the third major determinant of money demand. Friedman asserted that these preferences remain relatively constant “over significant stretches of space and time.” In summary, Friedman said that the amount of money demanded varies directly with permanent real income and the price level, inversely with the expected rate of inflation, and insignificantly with changes in the rate of interest. The modern quantity theory of money. According to Friedman, the demand for money is relatively stable in the short run. The Federal Reserve (Fed) System controls the supply of money. An increase in the supply of money will leave people holding cash balances in excess of amounts they want. They will attempt to rid themselves of these excess transaction assets by spending cash and writing checks. But the community as a whole cannot rid itself of excess cash balances; one person’s spending leaves more cash in someone else’s billfold or checkbook. Thus, the attempt by people to rid themselves of cash balances will drive up the demand for goods and services and increase output, prices, or some combination of each. In circumstances wherein the economy is operating at its natural levels of employment and output, only prices will rise over the long run. As the price level rises, the demand for money increases (recall our previous discussion) because the community desires to hold additional money to buy the higher priced goods. Eventually, equilibrium between the quantity of money supplied and demanded is restored, but at a higher price level. Thus, according to Friedman, the modern quantity theory of money is established. It does not assume that velocity is a constant as did the older quantity theory, but rather that the demand for money is “highly stable—more stable than functions such as the consumption function that are offered as alternative key relations.” Inflation, stated Friedman, “is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, produced in the first instance by an unduly rapid growth in the quantity of money.”6 This relationship between the money stock and prices, said Friedman, is confirmed by empirical evidence. Referring to studies done by others, he stated in 1956: There is perhaps no other empirical relation in economics that has been observed to recur so uniformly under so wide a variety of circumstances as the relation between substantial changes over short periods in the stock of money and in prices; the one is invariably linked with the other and is in the same direction; this uniformity is, I suspect, of the same order as many of the uniformities that form the basis of the physical sciences.7 In 1963, Friedman and Anna Schwartz published A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960, in which they presented their own empirical findings linking the growth of the money stock and the rate of inflation. Friedman considers this to be his most important book. 6 Milton Friedman, Dollars and Deficits (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1968), 18. 7 Milton Friedman, “The Quantity Theory of Money—A Restatement,” in Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, ed. Milton Friedman (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956), 20–21. Chapter 24 THE CHICAGO SCHOOL—THE NEW CLASSICISM The cause of the Great Depression. In Chapter 7 of their book, Friedman and Schwartz reached the controversial conclusion that monetary policy was largely responsible for causing the Great Depression of the 1930s.8 Later, Friedman expressed his position as follows: Keynes and most other economists of the time believed that the Great Contraction in the United States occurred despite aggressive expansionary policies by the monetary authorities—that they did their best but their best was not good enough. Recent studies have demonstrated that the facts are precisely the reverse: the U.S. monetary authorities followed highly deflationary policies. The quantity of money in the United States fell by one-third in the course of the contraction. And it fell not because there were no willing borrowers—not because the horse would not drink. It fell because the Federal Reserve System forced or permitted a sharp reduction in the monetary base, because it failed to exercise the responsibilities assigned to it in the Federal Reserve Act to provide liquidity to the banking system. The Great Contraction is tragic testimony to the power of monetary policy—not as Keynes and so many of his contemporaries believed, evidence of impotence.9 The long-run vertical Phillips curve. Recall that Wicksell had differentiated between the actual and natural rates of interest. Friedman said there is a similar distinction between the actual and natural rates of unemployment: “I use the term ‘natural’ for the same reason Wicksell did—to try to separate the real forces from monetary forces.”10 The natural rate of unemployment, said Friedman, is the one that will occur when the actual rate of inflation and the expected rate of inflation are equal. Authorities can push the actual rate of unemployment temporarily below the natural rate only by generating a level of inflation that is greater than expected. But once people adjust their expectations to the new higher rate of inflation, the natural rate of unemployment will return. Friedman’s analysis is formalized in Figure 24-1.11 Our expository approach first will be to establish a short-run Phillips curve and then to explain how such short-run curves can shift upward to produce a vertical long-run curve. This figure is sometimes referred to as the Phelps-Friedman Phillips Curve, as Edmund Phelps (1933–) articulated the same ideas and earned the Nobel Prize in economics in 2006 for his work.12 8 This chapter was published separately as the central portion of Friedman and Schwartz’s The Great Contraction (Princeton University Press, 1963). 9 Milton Friedman, “The Quantity Theory of Money—A Restatement,” in Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, ed. Milton Friedman (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956), 20–21. 10 Milton Friedman, “The Role of Monetary Policy,” in The Optimum Quantity of Money and Other Essays (Chicago: Aldine, 1969), 105. This paper was presented as the Presidential Address to the American Economic Association in 1967. 11 Friedman developed the ideas underlying this figure in his Nobel lecture reprinted as “Inflation and Unemployment,” Journal of Political Economy 85 (June 1977): 451–472. 12 Edmund Phelps, “Phillips Curves, Expectations of Inflation and Optimal Unemployment over Time,” Economica 34 (1967), 254-281. Other names for Figure 24-1 include the Friedman-Phelps Phillips Curve and the expectations-augmented Phillips Curve. 537 538 Chapter 24 THE CHICAGO SCHOOL—THE NEW CLASSICISM Figure 24-1 Friedman’s Long-Run Vertical Phillips Curve Each short-run Phillips curve shows the combinations of inflation and unem- ployment that are possible when the actual rate of inflation diverges from the expected rate. When inflation is greater than expected, such as P2 rather than P1, unemployment temporarily falls below its natural rate (from Un to U1, as shown at b). But once P2 becomes the new expected rate, the short- run Phillips curve shifts from SRPC1 to SRPC2 and the rate of unemployment returns to its natural level (point c). In the long run, said Friedman, there is no trade-off between inflation and unemployment. The long-run Phillips curve is vertical, indicating that any one of several rates of inflation is compatible with the natural rate of unemployment. © Cengage Learning 2013 Initially, let’s focus on the short-run Phillips curve SRPC1 in Figure 24-1. Sup- pose that the rate of inflation is P1 and unemployment is at the natural rate Un (point a). Next suppose that the monetary authorities desire to peg the actual rate of unemployment at U1, in a sense indicating a willingness to trade off higher inflation (P2 rather than P1) for a lower rate of unemployment. Suppose that the monetary authorities increase the stock of money to accomplish this. This eventually raises the rate of inflation to P2 and temporarily reduces unemployment to U1 (point b). The reasons? Firms discover that their product prices are rising faster than their unit labor costs. The labor contracts under which many employees are working were set on the expectation that inflation would continue to be P1. Because prices rise and nominal wages remain unchanged, real wage rates fall and employers respond by increasing employment. In addition, unemployed workers seeking jobs begin to receive higher nominal wage offers as firms bid for new employees. If workers mistake these nominal wage increases for better real wage offers, they will shorten the length of time they search for jobs. The result will be a lower rate of frictional unemployment. Conclusions: (1) When the actual rate of inflation exceeds the expected rate (P2 rather than P1), unemployment will fall (Un to U1); and (2) points on a short- run Phillips curve (for example, SRPC1) show the various rates of unemployment associated with rates of actual inflation that differ from the expected rate.