Burmese phonology

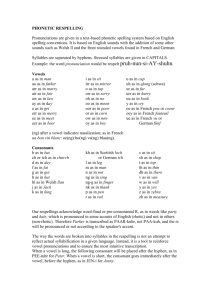

Consonants[edit]

Burmese has 34 consonant phonemes. Stops and affricates make a three-way contrast with voiced, voiceless, and voiceless

aspirated. A two-way voicing contrast is also present with nasals and all approximants except for /j/.[1][2]

Consonant phonemes[3]

Nasal

Stop

Bilabial Dental Alveolar

Post-al.

Velar Laryngeal

/Palatal

voiced

m

n

ɲ

ŋ

voiceless

m̥

n̥

ɲ̊

ŋ̊

Voiced

b

d

dʒ

ɡ

plain

p

t

tʃ

k

tʰ

tʃʰ

kʰ

aspirated pʰ

voiced

Fricative

voiceless

aspirated

Approximant

ð

θ

ʔ

z

1

s

ʃ

sʰ2

voiced

l

voiceless

l̥

h

j

3

w

ʍ4

Phonetic notes:

^1 ⟨သ⟩, which was */s/ in Pali and OB, but was shifted forward by the shift of ⟨စ⟩ */ts/→/s/, is often transliterated as ⟨s⟩ and

transcribed /θ/ in MSB but its actual pronunciation is closer to /ɾ̪ʰ~ɾ̪θ~tθ̆/, a dental flap, often accompanied by aspiration or a slight

dental fricative, although it can also be voiced.[citation needed] It has a short release generated by moving the tongue back sharply from

an interdental position, and will sound to English speakers like a short dental fricative combined with elements of a tap or

stop. /ð/ is the voiced allophone of ⟨သ⟩ and is not itself a phoneme.

^2 /sʰ/ is a complex phoneme to define. It is a reflex of the earlier /tʃʰ/ and then /tsʰ/ consonants. It is still distinguished from /s/

although it is not so much aspirated as pronounced breathy, and imparts a slight breathy quality to the following vowel [citation

needed]

making [s̤] a more accurate transcription.

^3 /j/ is often realised as [ʝ], particularly word initially.[citation needed]

^4 /ʍ/ is rare, having disappeared from modern Burmese, except in transcriptions of foreign names and a handful of native words.

An additional rare /ɹ/ occurs,[4] but this only appears in toponyms and personal names that have retained Sanskrit or Pali

pronunciations (such as Amarapura, pronounced àməɹa̰pùɹa̰ and in English-derived words. Historically, /ɹ/ became /j/ in Burmese,

and is usually replaced by /j/ in Pāli loanwords, e.g. ရဟန္တာ ra.hanta [jəhàndà] ('monk'), ရာဇ raja. [jàza̰] ('king'). Occasionally it is

replaced with /l/ (e.g., တိရ စ္ဆာန် ti.rac hcan 'animal'), pronounced [təɹeɪʔ sʰã̀] or [təleɪʔ sʰã̀].

Medials and palatalisation[edit]

Burmese permits the palatalisation of certain consonants. Besides [u̯ ], which is often erroneously treated as a medial [w] (see

vowels)[clarification needed], Burmese only permits the palatal medial. This is derived from Old Burmese */-j-/ */-l-/ and */-ɹ-/, and is,

therefore, reflected in various ways in different dialects. In MSB orthography, two spellings exist for the medial (demonstrated on

the consonant ⟨က⟩ /k/), one reflecting an original /-j-/ (⟨ကျ⟩ - /kj/), and one an original /-ɹ-/ (⟨ကက⟩ - /kɹ/). Official government

romanistion still reflects this fact, as Myanmar, in official romanistion is rendered mran-ma.

The letter ⟨လ⟩ represents /l/ in initial position, but as a medial, it has completely merged with /j/ and /ɹ/. In OB inscriptions, this

medial could be rendered with a subscript or "stacked" ⟨လ⟩ as in ⟨ကလ⟩, a practice still used in the rare dialects, such as

Tavoyan/Dawe where medial /l/ is still pronounced distinctly. Although the palatalisation of the labials is simple /m pʰ p b/ → [mʲ pç

pʲ bʲ], and the velar nasal predictably palatalises into a palatal nasal /ŋ/ → [n̠ ʲ]. The palatalisation of /l/ leads, ostensibly to [lʲ];

however, it often causes vowel raising or breaking, and may remain unchanged before /i/. The velar stops /kʰ k ɡ/ palatalise into [tʃʰ

tʃ dʒ]}}.

The alveolars /n tʰ t d/ and historical palatals /ɲ̊ sʰ s z/ cannot be followed by medials except in loan words, but even this is rare.

Indeed, the letter *jʰ ⟨ဈ⟩ [z, sʰ] is almost indistinguishable from the s+y sequence ⟨စျ⟩ and many combinations of alveolar+medial

will render poorly in certain font sets which were not designed to handle non-native combined graphs.

The homorganic nasal and glottal stop[edit]

Only two consonants can occur word finally in native vocabulary:[5] the homorganic or placeless nasal, and the

homorganic or glottal stop. These bear some similarities to the Japanese moraic n, ン and sokuon っ.

The glottal stop /ʔ/ is the realisation of all four possible final consonants: ⟨ပ်⟩ /p/, ⟨တ်⟩ /t/, ⟨စ်⟩ /s/, ⟨က်⟩ /k/, and the

retroflex ⟨ဋ်⟩ /ʈ/ found in loan words. It has the effect of shortening the vowel and precluding it from bearing tone. This

itself is often referred to as the "checked" or "entering" tone, following Chinese nomenclature. It can be realised as a

geminate of a following stop, although this is purely allophonic and optional as the difference between the sequence

/VʔtV/ and /VtːV/ is only in the catch, and thus barely audible. The primary indicator of this final is the impact on the

vowel.

The final nasal /ɰ̃ / is the value of the four native final nasals: ⟨မ်⟩ /m/, ⟨န်⟩ /n/, ⟨ဉ်⟩ /ɲ/, ⟨င်⟩ /ŋ/, as well as the retroflex

⟨ဏ⟩ /ɳ/ (used in Pali loans) and nasalisation mark anusvara demonstrated here above ka (က → ကံ) which most often

stands in for a homorganic nasal word medially as in တံခ ါး tankhá ('door', and တံတ ါး tantá ('bridge') or else replaces

final -m ⟨မ်⟩ in both Pali and native vocabulary, especially after the OB vowel *u e.g. ငံ ngam ('salty'), သံါး thóum ('three;

use'), and ဆံါး sóum ('end'). It does not, however, apply to ⟨ည်⟩ which is never realised as a nasal, but rather as an open

front vowel [iː] [eː] or [ɛː]. The final nasal is usually realised as nasalisation of the vowel. It may also allophonically

appear as a homorganic nasal before stops. For example, in /mòʊɰ̃ dáɪɰ̃ / ('storm'), which is pronounced [mõ̀ũndãĩ́ ].

Series of stops[edit]

Burmese orthography is based on Brahmic script and can perfectly transcribe words from Pali, an Indic language. As a

result, Burmese script uses far more symbols than Burmese needs for its phonemic inventory. Besides the set of

retroflex consonants ⟨ဌ⟩ /ʈʰ/, ⟨ဋ⟩ /ʈ/, ⟨ဍ⟩ /ɖ/, ⟨ဎ⟩ /ɖʰ/, ⟨ဏ⟩ /ɳ/, and ⟨ဠ⟩ /ɭ/, which are pronounced as alveolar in

Burmese. All stops come in sets of four: voiceless aspirated, voiceless, voiced, and voiced aspirated or murmured. The

first set ⟨ဖ⟩ /pʰ/, ⟨ထ⟩ /tʰ/, ⟨ဆ⟩ /sʰ/, and ⟨ခ⟩ /kʰ/, as well as the second set ⟨ပ⟩ /p/, ⟨တ⟩ /t/, ⟨စ⟩ /s/, and ⟨က⟩ /k/ are

commonly used in Burmese. The voiced set ⟨ဗ⟩ /b/, ⟨ဒ⟩ /d/, ⟨ဇ⟩ /z/, and ⟨ဂ⟩ /ɡ/ are used in Burmese, but sparingly. They

are frequently seen in loans from Pali. It may be possible to say that they exist only in loans; however, some of the

words they appear in are so old and deeply integrated into the language that the three-way voicing/aspiration

distinction can still be said to be an important part of the language. The final set ⟨ဘ⟩ /bʰ/, ⟨ဓ⟩ /dʰ/, ⟨ဈ⟩ /zʰ/, and

⟨ဃ⟩ /ɡʰ/ are exceedingly rare. They are generally pronounced as voiced [b d z ɡ] or, when following a syllable final stop,

aspirated [pʰ tʰ sʰ kʰ]. The most common by far is ⟨ဘ⟩ used in the negative indicative verb particle ဘါး bhú [búː] or

[pʰúː], and also in some common loans. Indeed, ⟨ဘ⟩ can be said to be the "default" spelling of /b/ in Burmese for loans

and ⟨ဗ⟩ is restricted to older loans.

Burmese voicing sandhi[edit]

Burmese exhibits voicing sandhi. Traditionally, Burmese has voiced voiceless unaspirated stops into voiced stops, which

at first, was allophonic. However, due to the influx of phonemeic voiced stops from loan words, and owing to the

extension of sandhi to voiceless aspirated stops as well – a feature which does not affect more conservative dialects –

sandhi has become an important part of Burmese phonology and word building. In brief, the following shifts can occur in

MSB:

/kʰ, k/ → /ɡ/

/tʃʰ, tʃ/ → /dʒ/

/sʰ, s/ → /z/

/tʰ, t/ → /d/

/pʰ, p/ → /b/

Additionally ⟨သ⟩ can become voiced under the same conditions, however this is purely allophonic since the

voiced [ɾ̪~ð̆ ~d̪̪̆ ] phone does not exist in any other context.

Sandhi can occur in two environments. In the first environment, consonants become voiced between vowels or after

nasals. This is similar to rendaku in Japanese.[6] This Therefore, can affect any consonant except the first consonant of the

phrase or a consonant preceded by a stop.

e.g. "hot water": [jèbù] ရရပူ ← /jè/ + /pù/

The second environment occurs around reduced syllables (see reduction for more). When a syllable becomes reduced,

the vowel and any final consonants are reduced to a short schwa [ə̪̆]. Reduction cannot occur in the final syllable of a

word. When a syllable becomes reduced, if both the consonant preceding and following the schwa – i.e. the consonant

of the reduced syllable and the consonant of the following syllable – are stops, then both will be voiced:[6]

e.g. "promise": [ɡədḭ] ကတိ ← /ka̰/ + /tḭ/

In some compound works, the phoneme /dʒ/, when following the nasalized final /ɰ̃ /, can shift to a /j/ sound:

e.g. "blouse" (အကကျီ angkyi): /èɪɰ̃ dʒí/] → [èɪ̃jí].

The phonemes /p, pʰ, b, t, tʰ, d/, when following the nasalized final /ɰ̃ /, can become /m/ in compound words:

e.g. "to consult" တိင

ို ပ

် င်: /tàɪɰ̃ pɪ̀ɴ/ → [tàɪm mɪ̃]̀

e.g. "to apologize" ရတာင််းပန်: /táʊɰ̃ pàɴ/ → [táʊm mã̀]

e.g. "airplane" ရေယာဉ်ပျီ:ျံ /lèi jɪ̀ɰ̃ pjàɴ/ → [lèɪm mjã̀]

Aspiration and devoicing[edit]

Although Burmese natively contrasts unaspirated and aspirated stops, there is an additional

devoicing/aspirating feature. In OB, h- or a syllable beginning with /h/ could be prefixed to roots, merging

over time with the consonant of the following syllable. In the case of the unaspirated stops, these are

replaced with the aspirated letter, however words beginning with

⟨မ⟩ /m/ ⟨န⟩ /n/ ⟨ည⟩ /ɲ/ ⟨င⟩ /ŋ/ ⟨လ⟩ /l/ ⟨ရ⟩ /j/ ⟨ယ⟩ /j/ ⟨ဝ⟩ /w/ use a subscript diacritic called ha-to to indicate

devoicing: ⟨မှ နှ ညှ ငှ လှ ရှ ယှ ဝှ⟩ /m̥ n̥ ɲ̊ ŋ̊ l̥ ʃ ʃ ʍ/, although as noted above, /ʍ/ is incredibly rare. Devoicing in

Burmese is not strong, particularly not on nasals. The sequence /n̥a/ is pronounced closer

to [n̤a̤] than [n̥na] and is more noticeable in its tone raising effects.

In many Burmese verbs, pre-aspiration and post-aspiration distinguishes

the causative and non-causative forms of verbs, where the aspirated initial consonant indicates active

voice or a transitive verb, while an unaspirated initial consonant indicates passive voice or an intransitive

verb:[7]

e.g. "to cook" [tʃʰɛʔ], ချီက် vs. "to be cooked" [tʃɛʔ], ကျီက်

e.g. "to loosen" [pʰjè], ရ ြေ vs. "to be loosened" [pjè], ရ ပ

e.g. "to elevate" [m̥jɪ]̃ ,

ြှင် vs. "to be elevated" [mjɪ]̃ ,

င်

Vowels[edit]

The vowels of Burmese are:

Vowel phonemes[8][3][9]

Front

Close

oral

nasal

i

ĩ

Close-mid e

Open-mid (ɛ)

Open

Central

Back

oral

oral

nasal

u

ũ

nasal

(o)

(ə)

a

ɔ

ã

In addition to the above monophthongs, Burmese also has nasal and oral

diphthongs: /ai/ /au/ /ei/ /ou/ /ãĩ/ /ãũ/ /ẽĩ/ /õũ/.[10][3] There is debate on the phonemicity of some of the

above vowels. For example, Chang (2003) argues that [ɛ] is an allophone of /e/ in closed syllables

(those with a syllable coda) and [ə] is a reduced allophone of other vowels.[11] The

monophthongs /e/, /o/, /ə/, and /ɔ/ occur only in open syllables (those without a syllable coda); the

diphthongs /ai/, and /au/ occur only in closed syllables. [ə] only occurs in a minor syllable, and is the

only vowel that is permitted in a minor syllable (see below).

The close vowels /i/ and /u/ and the close portions of the diphthongs are somewhat mid-centralized ([ɪ,

ʊ]) in closed syllables, i.e. before /ɴ/ and /ʔ/. Thus န္ှစ္် /n̥iʔ/ ('two') is

phonetically [n̥ɪʔ] and ရ ကာင် /tʃàuɴ/ ('cat') is phonetically [tʃàʊɴ].

Although this analysis is (more or less) correct from a purely phonetic point of view, it hides the

diachronic nature of Burmese vowel development and mergers, and obfuscates the reasoning behind

Burmese orthography.

Vowels in open syllables[edit]

Synchronically, there can be said to be a total of 10 vowels in Modern Standard Burmese (MSB) open

syllables: /a/ /u̯a/ /ɛ/ /u̯ɛ/ /e/ /u̯e/ /i/ /ɔ/ /o/ /u/. Although the vowels /u̯a/ /u̯ɛ/ /u̯e/ are commonly treated

as medial-vowel sequences, reducing the vowel inventory of MSB in open syllables from 10 to 7, the

behaviour of /u̯a/ /u̯ɛ/ /u̯e/ is unlike that of glide-vowel combinations (See the section on glides

below for a more complete explanation).

Diachronically, however, all of the MSB open syllable vowels are derived from Old Burmese (OB) open

syllables or diphthongs. The four vowels of OB were */a/ */i/ */o/ */u/. Early in the development of

Burmese */o/ broke to form */u̯a/. Additionally, any vowel could be followed by either of two glides: */j/

and */w/. The diphthongs which result from these glides were considered to be closed syllables in OB

and as such, could not be followed by any other consonant. However, in MSB, all OB diphthongs have

become monophthongs and are thus phonetically viewed as open syllables.

The following table shows the origins of MBS open vowels. The IPA is followed by the phoneme

demonstrated in Burmese script on the consonant ⟨ပ⟩ /p/ showing (top to bottom) creaky tone, low

tone, and high tone.

Outcomes of OB vowel + final combinations (Open Syllables)

OB final

OB vowel

*a

*o

ပ

*Ø

*y

/a/

/ɛ/

ပ

*i

ပွ

/u̯ a/

ပွ

*u

ပိ

/i/

ပီ

ပ

/u/

ပ ါး

ပွ ါး

ပီါး

ပါး

ပဲ့

ပွွဲ့

ပပဲ့

ပပွွဲ့

ပယ်

ပ

/u̯ ɛ/

ပွယ်

ပွ

/e/

ပပ

/u̯ e/

ပပါး

/ɔ/

ပပေါ်

ပပ

ပပွ

ပပွါး

ပပ ဲ့

*w

ပ

ပိ ဲ့

/o/

ပိ

ပိါး

From the table it is clear that the vowels /ɛ/ /u̯ɛ/ /e/ /u̯e/ /ɔ/ /o/ can only exist in open syllables in MSB

(with some rare exceptions) as they derive from vowel+glide combinations.

The /j/ offglide results in the e-class vowels */aj/→/ɛ/, */ij/→/e/, */u̯aj/→/u̯ɛ/, */uj/→/u̯e/ respectively.

Note the symmetry with the base vowel system: The closed vowels */i/ and */u/ create the mid-closed

vowels /e/ and /u̯e/ while */a/ and */o/ create the mid-open vowels /ɛ/ and /u̯ɛ/. Similarly, the rounded onglide is a result of a rounded base vowel */u/ or */o/.

Currently, the /w/ offglide is only believed to have existed in */aw/ and */uw/ resulting in the MSB o-class

vowels /ɔ/ and /o/ respectively. The absence of */iw/ and */ow/ in reconstructions is something of a

mystery, however it is possible that, by analogy with the /j/ offglide, */aw/ */iw/ */ow/ */uw/ all existed,

resulting in pairs with or without the rounded on-glide: /ɔ/ /o/ /u̯ɔ/ /u̯o/ which later merged. This may

explain why the Burmese orthography indicates the vowel /o/ with both the diacritics for both the /i/ and

/u/ vowels and, previously, a following consonantal /w/.

Finals[edit]

MSB recognises 8 finals in native vocabulary which are all distinguished from their initial forms with the

c-shaped superscript diacritic asat ⟨ ်် ⟩ which for ease of reading, is omitted here: the stops: ပ /p/ တ /t/

စ /c/[12] က /k/ and the nasals: မ /m/ န /n/ ည / ဉ /ɲ/[13] င /ŋ/. All of the stops in final position are realised as a

glottal stop /ʔ/ (or, potentially, a geminate of a following stop) which shortens the vowel and precludes it

from bearing any tone.[14] All of the nasals on the other hand nasalise the vowel but are not pronounced

as consonants unless there is a following nasal or stop. Syllables ending on nasals can bear any of the

three tones, but rarely have tone 1 (short, high, creaky phonation).

Finals are broadly grouped into two sets: front and back finals. Front finals include the labial and

alveolar finals -m -n and -p -t which are not distinguished in MSB, leading to mergers such as အိပ် (*/ip/

sleep) and အိတ် (*/it/ bag), both pronounced [ĕɪʔ]. In Tavoyan dialects however, the labial finals -m and p often cause vowel breaking (*/un/ -> /ũː/, */um/ -> /ãʊ/). The back finals include the palatal finals -c ɲ and velar -k -ŋ, although their uses are even more complex.

Current reconstruction holds that the OB vowel-offglide sequences – which today are /ɛ/ /u̯ɛ/ /e/ /u̯e/ /ɔ/

/o/ in MSB – counted as a closed syllables and thus could not be followed by a final. As a result, most

closed syllables in MSB are built around the 4 basic vowels /a/ /i/ /u̯a/ /u/.

Vowels before labial and coronal finals[edit]

The 4 basic vowels /a/ /i/ /u̯a/ /u/ can all occur before the labial and coronal finals. In MSB before the p and -t finals they are pronounced /æʔ/ /eɪʔ/ /u̯æʔ~ʊʔ/ /ɔʊʔ/ respectively. Similarly, before the -m and n finals, vowels use the same qualities except that they are nasalised and are pronounced long by

default[15] thus giving: /æ̃/ /ẽɪ/ /u̯æ̃~ʊ̃/ /ɔ̃ʊ/.

The variation between /ʊ̆ʔ/ /ʊ̃ː/ and /u̯æ̆ʔ/ /u̯æ̃ː/ is regional. North-central dialects in and around

Mandalay tend to use the original opening diphthong while southern dialects in and around Yangon tend

to use the monophthong. Both pronunciations are universally accepted and understood. In more

conservative dialects /i/ /u/ and */o/ may not break, and thus remain /ĭʔ/ /ĩ/, /ŭʔ/ /ũ/, and /ɔ̆ʔ/ /ɔ̃/,

additionally */an/ may move back, not forward, leaving /ɔ̃/ and not /æ̃/, but all of these features are

considered non-standard.

Some exceptions do exist to this rule, however, as even in Yangon Burmese the word စွမ်ါး (*suám

"power") is pronounced /su̯áːN/ while ဆွမ်ါး (*sʰuám "religious offering of food"), written with the same

rime and tone, is pronounced /s(ʰ)ʊ́ːN/.

In Tavoyan dialects, labial finals are often distinguished from coronal finals by breaking and rounding

vowels.

Vowels before dorsal finals[edit]

The velar finals ⟨က⟩ -k and ⟨င⟩ -ŋ can follow the vowels /a/ and /u̯a/ giving အက် /ɐʔ/ အွက် /u̯æʔ/ အင် /ɪ/̃

အွင် /u̯ɪ/̃ . The pronunciation of -ak is becoming /æʔ/ in Yangon Burmese, merging with -ap and -at. Older

speakers will pronounce the vowel higher and as a front-central vowel in the [ɛ~ɜ] range. The fronting of

*a before *ŋ to /ɪ/ is a distinctive feature of MSB, not shared by other varieties of Burmese.

Rakhine/Arakhanese dialects shift the /a/ back before both the stop and nasal to become /ɔ̆ʔ/ /ɔ̃ː/.

Tavoyan/Dawei dialects merge both the -ap -at -ak rimes (as is becoming common in Yangon) and also

merge the -am -an -aŋ rimes allegedly resulting in /ăʔ/ /ãː/, although it is unclear whether these are truly

[a] or [æ] as in MSB..

The palatal finals ⟨စ⟩ and ⟨ည / ဉ⟩ occur only with the inherent vowel /a/ and derive from OB *ik and *iŋ.

The spelling reflects the shifts of *ik > *ac and *iŋ > aɲ. The final ⟨စ⟩ today is /ɪʔ/. The palatal final,

however, has two forms. The form ⟨ဉ⟩ represents /ĩ/ (or /ãɪ/ in Rakhine dialects) as would be expected.

The far more common ⟨ည⟩ however has lost its nasal characteristic and is realised variously as /ɛ/ (မည်

/mɛ̀/ literary future/irrealis marker, written မယ် in colloquial language), /i/ (ပပည် /pʲì/ "country" pronounced

as ပပီ "end, finish"), and less often /e/ (ရည် /jè/ "juice", pronounced identically to ပရ "water"). Tavoyan

dialects restrict the pronunciation to /ɛ/ exclusively, while Rakhine dialects use /e/.

The rimes */aʊk/ (ပအ က်) */aʊŋ/ (ပအ င်) derive from OB *uk and *uŋ breaking to /aʊ/ before a velar

final. The change in spelling reflects this sound shift and should not be taken to indicate an OB *awk

*awŋ or *ɔk *ɔŋ sequence. In Tavoyan they are realised as /ɔ̆ʔ/ and /ɔ̃ː/ respectively.

The rimes (အိက်) and (အိင်) are somewhat problematic from a linguistic perspective. Written with the

compound vowel diacritic for /o/ and pronounced /ăɪʔ/ and /ãɪ/ respectively, they are currently believed

to represent either loans from foreign languages or from more conservative dialects of Burmese. They

do not fit into the normal table of rimes and their shared orthography with the /o/ vowel is coincidental.

The closed syllable vowel inventory[edit]

Just as open syllables have ten vowels, so too do closed syllables: /æ/ /ɪ/ /ɛ~ɜ/ /u̯æ~ʊ/ /u̯ɛ/ /u̯ɪ/ /eɪ/ /oʊ/

/aɪ/ /aʊ/. It is worth noting that in Yangon MSB no vowel quality exists in both closed and open syllables,

and that therefore nasalisation and the glottal stop cannot be said to be contrastive features in and of

themselves. In fact, with the exception of tone (and its inherent length, intensity, and phonation) no

supgrasegmental features can really be said to be phonemic.

Finals in loans[edit]

Following the breaking of *u to /aʊ/ before velars and the palatalisation of velars after *i, new vocabulary

entered the language with sequences of /i/ or /u/ followed by a velar. Such words are written with the

vowel ⟨အိ⟩ or ⟨အ⟩ and followed by the velar final, and are pronounced as though they ended on a labial

or coronal final. Thus, လိင် /lèɪN/ "sex" is pronounced as လိမ် "to twist, cheat" and သက် (semen) is

pronounced exactly as သပ် (salad) /ɾ̪ɔʊʔ/ (or /θɔʊʔ/ following conventional transcription).

In loan words, usually from Pali, လ /l/ ရ /ɹ~j/ ဝ /w/ သ /s/[16] are found but are silent and do not affect the

vowel, which continues to behave as an open syllable vowel. Also from Pali are the retroflex finals ဋ /ʈ/

and ဏ /ɳ/ which merge with their alveolar counterparts.

The superscript diacritic ⟨ ်ံ ⟩ anusvara is a convention inherited from Pali. It is used across Brahmic

scripts in homorganic nasal+plosive sequences as a shorthand for the nasal (which would ortherwise

have to carry an asat or form a ligature with the following stop). In Burmese it continues this function as

it is found not only in loaned vocabulary but also in native words e.g. သံါး /ɾ̪óʊːN/ (or /θóʊːN/) "three" or

"to use" which derives from proto-Sino-Tibetan *g-sum.

The consonant ⟨ယ⟩ is also seen with an asat diacritic, but this is the standard spelling for the vowel /ɛ/

with tone 2 and is not viewed in any way as a final (although, as noted above, this is an etymologically

accurate rendering of /ɛ/ which originated from the *ay sequence).

Finally, loaned vocabulary can also, uniquely, add a

final after the vowel /e/. An example of this is the common Pali word ပမတတ mettā, from Sanskrit

मैत्र maitra. This is exclusively used to transcribe an /e/ vowel in closed syllables in loans, but cannot

occur in native vocabulary, although many such loans, particularly from Pali, may be centuries old.

Notes on glides[edit]

Note that, the vocalic onglide /u̯/ is usually transcribed both in phonetic transcription and in romanisation

as /w/. This is due to the fact that, phonetically, it behaves as a medial, however, here the transcription

/u̯/ is used to emphasise that it is a part of the vowel and not a true medial like /-j-/ (romanised -y-). /-j-/

is derived from OB */-j-/ */-l-/ and */-ɹ-/, and is, therefore, reflected in various ways in different dialects. In

MSB orthography two spellings exist for the medial (demonstrated on the consonant က /k/), one

reflecting an original /-j-/ (ကျ - ky), and one an original /-ɹ-/ (ကက - kr) and official government romanistion

still reflects this fact (Myanmar, in official romanistion is rendered mran-ma). However, in MSB, */ɹ/, for

which there is also a unique initial letter ⟨ရ⟩, is pronounced /j/ in all instances (usually realised as [ʝ]

initially) except in loan words. The letter for /l/ ⟨လ⟩ is still pronounced as /l/ in initial position, but as a

medial, it has completely merged with /-j-/ and /-ɹ-/. In OB inscriptions this medial could be rendered with

a subscript or “stacked” လ as in ⟨ကလ⟩, a practice still used in the rare dialects, such as Tavoyan/Dawe

where the /-l-/ medial is still pronounced distinctly. These medials behave differently than the /u̯/ onglide

in the following ways:

a medial */-j-/ */-l-/ */-ɹ-/ can be placed before the on-glide /u̯/, whereas two medials can never

be used in the same syllable.

the use of /u̯/ is restricted by the vowel nucleus (only used with /a/ /ɛ/ /e/) and may in some

cases drastically change the pronunciation of the vowel e.g. in Yangon /wa/ before a final becomes [ʊ],

while /a/ before a final becomes [æ]. However, it cannot affect the pronunciation of the initial.

glides are restricted by the preceding initial, and often change its pronunciation. Bearing in

mind that MSB does not reliably indicate the development of */-l-/, /m/ /pʰ/ /p/ /b/ can apparently be

followed by any glide, in which case the glide becomes [ʲ]. Similarly /kʰ/ /k/ and /g/ can be followed by

any glide, in which case the cluster becomes [tʃʰ] [tʃ] or [dʒ] respectively. /ŋ/ can be followed by /-ɹ-/ but

not /-j-/ in which case the cluster becomes [ɲ], merging with the palatal nasal letter ⟨ည / ဉ⟩. And finally,

/l/ can be followed by /-j-/ but not /-ɹ-/. This is rare and in Yangon MSB this represents the only case

where the medial impacts the vowel, whereby the sequence လျ */ljaː/ is realised [lea̯] and လျင်

becomes *lyaŋ > lyiŋ becomes [lɪə̃]. Although there is a lot of variation in the pronunciation of these

syllables. Tavoyan front vowels are frequently raised following /-j-/.

There is, at least in Yangon MSB, no difference

between an initial /j/ /ɹ/ /w/ and a null initial with /-j-/ /-ɹ-/ /u̯/. This extends to a /w/ initial followed by a /u̯/

onglide. Therefore, in Yangon (and likely much of MSB) /wa/, /Øu̯a/, and /wu̯a/ are pronounced

identically.

Tones[edit]

Burmese is a tonal language, which means phonemic contrasts can be made on the basis of the tone of

a vowel. In Burmese, these contrasts involve not only pitch, but also phonation, intensity (loudness),

duration, and vowel quality. However, some linguists consider Burmese a pitch-register

language like Shanghainese.[17]

Like most East and South-East Asian languages (Notably Chinese), the Burmese tone system

developed in the following way:

Syllables ending on a stop (-p, -t, -k) developed a unique tone, called checked or entering tone following

Chinese nomenclature (入 rù). Other syllables (i.e. those ending on a nasal, a glide, or no final) are

believed to have been able to end on an additional glottal stop [ʔ] and/or be glottalised [ˀ] or alternatively

they could end on a fricative, likely either /s/ or /h/. The loss of these final glottal and fricative created the

Burmese creaky and high tones respectively. Low tone is the result of syllables which had neither a

glottal nor fricative ending.

In this way, The Burmese creaky, low, and high tones correspond to the Middle Chinese rising (上

shǎng), level (平 píng), and departing (去 qù) tones respectively, as well as the Vietnamese tone pairs of

sắc & nặng, ngang & huyền, and hỏi & ngã respectively.

Creaky tone and high tone both have distinctive phonations—creaky and breathy respectively. They are

also notably shorter and longer than low tone respectively.

In the following table, the four tones are shown marked on the vowel /a/ as an example.

Tone

Symbol

Burmese (shown Phonation

on a)

Low

နိ ်သျံ

High

Creaky

Checked

တက်သျံ

သက်သျံ

တိင

ို သ

် ျံ

Duration Intensity Pitch

à

normal

medium

á

sometimes

slightly breathy

a̰

tense or creaky,

sometimes

medium

with lax glottal

stop

aʔ

centralized

vowel quality,

final glottal

stop

long

short

low

low, often

slightly

rising[9]

high

high, often

with a fall

before a

pause[9]

high

high, often

slightly

falling[9]

high

high

(in citation;

can vary in

context)[9]

For example, the following words are distinguished from each other only on the basis of tone:

Low ခ /kʰà/ "shake"

High ခ ါး /kʰá/ "be bitter"

Creaky ခ /kʰa̰/ "to strike"

Checked ခတ် /kʰæʔ/ "to beat"

In syllables ending with /ɰ̃/, the checked tone is excluded:

Low ခံ /kʰæ̀ɰ̃/ "undergo"

High ခန်ါး /kʰǽɰ̃/ "dry up"

Creaky ခန ် ဲ့/kʰæ̰ɰ̃/ "appoint"

As with many East and South-East Asian languages, the phonation of the initial consonant can trigger

a tone split - which explains why pairs of tones in Vietnamese correspond with single Burmese tones,

and why languages like Thai, Lao, and Cantonese have significantly more than 4 tones. Although this

feature has been historically absent from Burmese, a tone split is underway currently. Sonorants with

a ha-to (devoicing mark - see section on consonants) raise the tone of the following vowel.

Customarily, this distinction is transcribed with the letter h in romanisation and is explicitly marked on

the consonant in Burmese script e.g. မ (ma "woman") vs မှ (hma "from"). In earlier times this

distinction was borne primarily on the consonant in the form of devoicing/murmuring, then later

imparted a breathy quality to the vowel itself. More recently this has translated into a general tone

raising, even in checked syllables (i.e. those ending on a stop -p -t -k) representing the first time tonal

distinctions have occurred in such syllables e.g. ပပမ က် (*mruk /mʲaʊʔ/ "north") vs ပပမှ က် (*hmruk

/m̤ʲá̤ʊʔ/ "to raise"). Consequently, Burmese can be described as having 8 tones. Note that this does

not apply to devoiced r ရှ, y ယှ, or ly လျှ as this results in [ʃ] with no breathy phonation. In some

dialects, for instance those around Inle Lake, devoiced l လှ results in a voiceless lateral fricative /ɬ/,

making tone raising unlikely.

Reduced syllables have the rime [ə̀], which is short and low. This is not considered to be a distinct

tone, but rather the absence of distinct tone or rime all together.

In spoken Burmese, some linguists classify two real tones (there are four nominal tones transcribed in

written Burmese), "high" (applied to words that terminate with a stop or check, high-rising pitch) and

"ordinary" (unchecked and non-glottal words, with falling or lower pitch), with those tones

encompassing a variety of pitches.[18] The "ordinary" tone consists of a range of pitches. Linguist L. F.

Taylor concluded that "conversational rhythm and euphonic intonation possess importance" not found

in related tonal languages and that "its tonal system is now in an advanced state of decay." [18][19]

Syllable structure[edit]

The syllable structure of Burmese is C(G)V((V)C), which is to say the onset consists of a consonant optionally followed by

a glide, and the rime consists of a monophthong alone, a monophthong with a consonant, or a diphthong with a

consonant. The only consonants that can stand in the coda are /ʔ/ and /ɴ/. Some representative words are:

CV မယ် /mè/ 'girl'

CVC မက် /mɛʔ/ 'crave'

CGV ပပမ /mjè/ 'earth'

CGVC မျက် /mjɛʔ/ 'eye'

CVVC ပမ င် /màʊɰ̃ / (term of address for young men)

CGVVC ပပမ င်ါး /mjáʊɰ̃ / 'ditch'

A minor syllable has some restrictions:

It contains /ə/ as its only vowel

It must be an open syllable (no coda consonant)

It cannot bear tone

It has only a simple (C) onset (no glide after the consonant)

It must not be the final syllable of the word

Some examples of words containing minor syllables:

ခလတ် /kʰə.loʊʔ/ 'knob'

ပပလွ /pə.lwè/ 'flute'

သပရ ် /θə.jɔ̀/ 'mock'

ကလက် /kə.lɛʔ/ 'be wanton'

ထမင်ါးရည် /tʰə.mə.jè/ 'rice-water'

An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Tibeto-Burman, Lolo-Burmese, Burmish. A few minor languages of Yunnan and northern Myanmar are

closely related to Burmese, especially Lhao Vo (or Maru) and Zaiwa (or Atsi).

Overview. Burmese has the largest number of speakers among the Tibeto-Burman languages and, along with Tibetan,

has the longest written record. The Burmese settled in the lowlands of Burma drained by the Irrawaddy River and

emerged in history with the kingdom of Pagan in the 9th century. They fell under the spell of Indian culture and

Buddhism, transmitted by the Mon and Pyu peoples, which left a deep imprint in the Burmese lexicon and were the

source of its script.

Burmese is a tonal language and has a complex consonantal system. It has little or no inflectional morphology and

grammatical functions are carried out mainly by particles and word order.

Distribution. Burmese is spoken in Myanmar (formerly Burma), especially in the plains of the centre and south drained

by the Irrawaddy River. Burmese expatriates are found in small communities in Asia and around the world. One of the

largest lives in Bangladesh.

Myanmar is a multilingual country where up to one-hundred languages are spoken by ethnic minorities. From the

numerical viewpoint the most important are Mon and Karen in the south and southeast, Shan in the east and north,

and Kachin in the north. Kachin and Karen belong to Tibeto-Burman, Shan to Tai-Kadai, and Mon to Austroasiatic.

Besides, there are many smaller minority languages, found mostly in mountainous regions.

Speakers. About 35 million people in Myanmar speak Burmese as a first language (2/3 of the population). There are also

about 10 million or more second language speakers in the country. In Bangladesh live an additional 300,000 speakers.

Status. Burmese is the official language of Myanmar. It is the mother tongue of the Burman ethnic majority, who

constitute about two-thirds of the country’s population. The rest speaks several dozen languages belonging to TibetoBurman and other families.

Varieties.

Burmese has a colloquial style used in spoken informal contexts and a literary style used in official formal settings.

Besides, it has several dialects: Standard Burmese based on the speech of the lower valleys of the Irrawaddy and

Chindwin rivers, Arakanese in the south-west, Tavoyan in the south-east, Intha around Inle Lake, and Danu in the Shan

state.

Periods.

1100-1500. Old Burmese: attested by stone inscriptions and fragments of palm-leaf manuscripts written in ink, it has

considerable phonetic differences with the modern language but lesser ones at the grammatical level.

1500-1700. Middle Burmese: certain pairs of sounds merged giving rise to some confusion in spelling. These, plus other

sound changes, created a gap between the literary and the spoken language.

1700-present. Modern Burmese: differences between literary and spoken Burmese tend to diminish and the script has

been stabilized.

Oldest Documents

-The earliest attestation of Burmese is the twelfth-century Rajakumar inscription (1112 CE), found close to Myazedi

Pagoda, recording the offering of a gold Buddha image. It is written in four languages: Pali, Burmese, Mon and Pyu.

-Other early stone inscriptions, belonging to the Pagan and Ava periods and dating from the 12th-14th centuries.

Phonology

Word structure: Most native Burmese words are sesquisyllabic. A reduced or minor syllable is followed by a major or full

syllable. Some words have two minor syllables, instead of one, prefixed to a major one. Minor syllables are toneless,

have only an initial consonant and a vowel realized as schwa. The structure of major syllables is C1(w/y)V (C2). In them,

phonological contrasts are concentrated in the initial consonant (C1) and the vowel (V). The only possible medial

consonants are the glides w and y, and the only possible final consonants are a nasal or the glottal stop. Neither initial

nor final consonant clusters are possible. Each major syllable has one of four possible tones.

Vowels (8): Seven vowels are found in major syllables, while in minor syllables all vowels tend to schwa (ə).

Burmese has four diphthongs (ei, ai, au, ou), which are always followed by a nasal or the glottal stop.

Consonants (30-33): Burmese has three series of stops and affricates: voiceless unaspirated, voiceless aspirated and

voiced. It also has a full set of voiceless nasals, that are relatively rare in the world’s languages.

*sounds between brackets are of marginal use.

*[r] is rare and is only used in place names that have preserved Sanskrit or Pali pronunciations.

*[ʍ] is the voiceless counterpart of [w].

*[ɬ] is a voiceless lateral.

Tones: Like many Southeast Asian languages, Burmese is tonal. The tonal contrasts involve not only differences in pitch

and vowel length but also differences in voice quality (clear, breathy or creaky). The presence or absence of a glottal

stop at the end of a syllable is considered to be part of the tonal system. Burmese has four tones:

1) low: long, low, clear voice.

2) high: long, high, sometimes breathy voice.

3) creaky: short, high, creaky voice (pronounced with tension or constriction in the throat).

4) checked: very short, mid-high, clear voice with final glottal stop (which shortens the duration of the vowel).

Script and Orthography

Burmese is written from left to right in an alphabetic script derived,

ultimately, from the Brāhmī alphabet of India that is the ancestor of all Indic

scripts and of several Southeast Asian ones. Transmission of the script was

indirect: Brāhmī → a southern Indian script → Mon script → Burmese. The

Burmese script is also used to write other languages of Myanmar, like Shan

and Karen.

The Burmese alphabet has 33 consonants which represent not only native

sounds but also retroflex and voiced aspirated sounds found only in Indic

loanwords, like those of Sanskrit and Pali origin. A consonant sign without

any added vowel has an inherent vowel a; to represent other vowels, vowel

signs are added before, after, above or below consonant signs. The

arrangement of the alphabet reflects that of its Indian models. Below each

character figures its most common transliteration, and its phonetic

equivalent in the International Phonetic Alphabet between square brackets.

Low tone is unmarked. High tone is marked with a visarga (similar to a colon)

in the script and with a grave accent in transliteration. Creaky tone is

marked with a subscript dot in the script and by an acute accent in

transliteration Checked tone is indicated by a hook and is transliterated with

an apostrophe.

*the affricates [tʃ], [tʃʰ], [dʒ] are usually written ky, khy and gy, respectively.

*the palatal fricative [ʃ] is transliterated sh.

*the voiced palatal nasal [ɲ] is transliterated ny.

*the voiced velar nasal [ŋ] is transliterated ng.

*the voiceless nasals are distinguished from the voiced ones in writing by

adding an h: hm, hn, hny, hng.

*the voiceless lateral and glide are distinguished from the voiced ones in

writing by adding an h: hl, hw.

Morpho-syntax

Burmese is an isolating language with little or no inflectional morphology. Words are not inflected for person, number,

gender, case, tense, aspect or mood. Grammatical functions are carried out mainly by particles and word order.

Prefixation, reduplication and compounding serve to derive new words from preexisting ones (derivational morphology).

a)Noun

There is no grammatical gender. When natural gender has to be specified, -má (female) might be added after the noun

e.g. yáhàŋ ('monk'), yáhàŋ-má ('nun'). Plurality may be indicated by the general plural markers -te or -tó, or by the more

formal marker -myà which usually has a restrictive sense: lu ('man'), lu-te ('people'), lu-myà ('a certain number of

people').

When context is insufficient, syntactical relations may be expressed by particles following the noun,

like ha (subject), ká (contrasted subject, agent, topic, source), ko (object or goal), hma (location), nɛ́ (instrument,

company, manner), yɛ́/kɛ ́ (possession), mó (cause), p'ó (purpose).

Burmese, like many of the languages of mainland Southeast Asia and Northeast Asia, requires classifiers when nouns are

modified by a number. They encompass several broad semantic and conceptual groups like: monks (pà), ordinary people

(yauʔ), animals (kaun), clothes (t'ɛ), sacred objects (s'u), round things (lòun), etc. Numeral and classifier follow the

quantified noun in an appositional relationship.

Nouns are easily formed from verbs by prefixation and/or partial reduplication. Nominal compounds are commonplace.

b)Pronoun

For the first and second persons there are a variety of pronouns marking degrees of politeness and familiarity. Except for

the first person and second person pronouns ŋa and nin, Burmese pronouns derive from nouns. Kinship terms, titles,

and names can function also as pronouns, like s'əya ('teacher') or meisʔ'we ('friend'). Deictic pronouns distinguish

proximal and distal: di ('this, these, here'), ho ('that, those, there'). The interrogative pronouns are bɛθu ('who?')

and bago ('what?'). Pronouns can be made plural by the addition of the suffix -tó.

c)Verb

New verbs are created by compounding and not, like nouns, by affixation or reduplication. The verbal phrase often

consists of one or more head-verbs followed by auxiliary verbs, particles and markers. Person, number and voice are not

indicated. There are no real passives. Aspect (more than tense) is expressed by postpositional particles like:

mɛ: imperfective (incomplete action)

gɛ, kɛ́: perfective (complete action)

ne: progressive (ongoing action)

pyi: inceptive (beginning of an action)

Mood is also conveyed by postpositional particles:

pa: polite imperative

chiŋ: desiderative

ta' /hnain: potential

yá: necessitative

yiŋ: conditional

The negative marker is mɛ; an interrogative marker is la.

d) Word Order

In Burmese, the verb and its modifiers occupy the final position in the clause, with nominals and other complements

before it. The order of elements before the verb is in principle free though it is affected by topicalisation (the topic tends

to be mentioned first). Within the noun phrase, the order of constituents is, primarily, modifier before modified:

demonstratives precede their head, so do genitive phrases and other nominal modifiers, as well as most relative clauses.

There is neither agreement between constituents nor concord within them.

Lexicon

Mon, an Austroasiatic language of southern Myanmar, influenced Burmese vocabulary in the early period acting also

as a nexus with Indian culture. A number of Sanskrit loanwords were adopted through the intermediation of Mon. The

spread of Theravada Buddhism in the country made Pali an even greater source of new lexical material, particularly in

the domains of religion, philosophy and high culture.

Myanmar was under British colonial rule between 1886-1948 and English lent many words to Burmese; some of them

were later replaced by native or Indic forms but new ones appeared in the fields of science and technology, politics and

business. English loanwords are sometimes combined with Burmese words in compounds to coin new technical

vocabulary.

Basic Vocabulary

As there is no standard transliteration for Burmese and as there is considerable disagreement between spelling and

pronunciation, we give below the vocabulary in the International Phonetic Alphabet notation):

one: tiʔ

two: n̥ iʔ

three: θòuŋ

four: lèi

five: ŋà

six: ʧʰaʊʔ

seven: kʰú n̥ iʔ

eight: ʃiʔ

nine: kò

ten: sʰe

hundred: ya

father: əpha

mother: əmei

older brother: əko

younger brother: ɲi (of male), maʊ̃ (of female)

older sister: əmá

younger sister: n̥əma (of male), ɲimá (of female)

son: θà

daughter: θamì

head: gàʊ̃

eye: myeʔ

leg/foot: ʧʰi

heart: n̥əlòʊ̃

tongue: ʃa

Maltese Phonology

The charts below show the way in which the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) represents Maltese

language pronunciations in Wikipedia articles. For a guide to adding IPA characters to Wikipedia articles, see {{IPA-mt}}

and Wikipedia:Manual of Style/Pronunciation § Entering IPA characters.

Consonants

Vowels

IPA

Example

English approximation

IPA

Example

English approximation

b

ballun

boy

a

fatt

RP cat

d

dar

duck

ɐː / æː

rani

dz

gazzetta

pads

somewhat likeRP father or

somewhat like Australian rate

dʒ

ġelat

jail

eː

dehra

hey

f

fwieħa

four

ɛ

belt

met

ɡ

gallettina game

ɝ

merħba[2]

American nurse

ə

intom, Mdina (in

between m and d)[3]

minimum

iː

għid less focused a

sound than in the

word dik

beet

ɪ

wisa

bit

ɛː

wied,

met but longer

oː

sod, għum

Scottish no

h ħ ħadem

hat or Arabic ḥarām اْ ام ََر

j

jum

yes

k

kelb

scar

l

ɫ libsa

look

m

mara

mole

n

nadif

no

p

paġna

spat

ɹ r re

real or American better[1]

øː

ewwel (may be realised

as a Diphthong)

RP code or French ceux

s

saqaf

sow

ɔ/ɒ

moħħ

awe or off

ʃ

xadina

shell

uː

mur

pool

t

tieqa

stake

ʊ

kuntratt

look

ts

zokk

sits

yː

iwaħħax

tʃ

ċavetta

chew

somewhat like RP acute

or French tu

v

vazun

vet

w

warda

wall

għajn

Australian late

z

żaqq

zoo

ʔ

Luqa

Cockney button

Suprasegmentals

IPA Explanation

◌ˤ

pharyngealised vowel

◌ː

long vowel or geminate consonant[4]

.

syllable break

ˈ

stress

Diphthongs

æː(ɪ̯)

eʊ̯ øʊ̯ øː ewwel

RP code or French ceux

aʊ̯ ɑʊ̯

għawn

how

oɪ̯

bojod

boy

Phonology

Consonants

Consonant phonemes[32][33]

Labial

Nasal

Dental/

Palatal Velar Pharyngeal Glottal

Alveolar

m

Plosive

p b

Affricate

Fricative

f

v

n

t

d

t͡s

d͡z

t͡ ʃ

d͡ʒ

s

z

ʃ

ʒ

Trill

r

Approximant

l

k ɡ

j

ʔ

ħ

w

Vassalli's Storja tas-Sultân Ċiru (1831), is an example of Maltese orthography in the 19th century, before the later

standardisation introduced in 1924. Note the similarities with the various varieties of romanized Arabic.

Voiceless stops are only lightly aspirated and voiced stops are fully voiced. Voicing is carried over from the last segment

in obstruent clusters; thus, two- and three-obstruent clusters are either voiceless or voiced throughout, e.g. /niktbu/ is

realised [ˈniɡdbu] "we write" (similar assimilation phenomena occur in languages like French or Czech). Maltese

has final-obstruent devoicing of voiced obstruents and voiceless stops have no audible release, making voiceless–voiced

pairs phonetically indistinguishable.[34]

Gemination is distinctive word-medially and word-finally in Maltese. The distinction is most rigid intervocalically after a

stressed vowel. Stressed, word-final closed syllables with short vowels end in a long consonant, and those with a long

vowel in a single consonant; the only exception is where historic *ʕ and *ɣ meant the compensatory lengthening of the

succeeding vowel. Some speakers have lost length distinction in clusters.[35]

The two nasals /m/ and /n/ assimilate for place of articulation in clusters.[36] /t/ and /d/ are usually dental, whereas /t͡s

d͡z s z n r l/ are all alveolar. /t͡s d͡z/ are found mostly in words of Italian origin, retaining length (if not wordinitial).[37] /d͡z/ and /ʒ/ are only found in loanwords, e.g. /ɡad͡zd͡zɛtta/ "newspaper" and /tɛlɛˈviʒin/ "television".[38] The

pharyngeal fricative /ħ/ is velar ([x]) or glottal ([h]) for some speakers.[39]

Vowels[edit]

Maltese has five short vowels, /ɐ ɛ ɪ ɔ ʊ/, written a e i o u; six long vowels, /ɐː ɛː ɪː iː ɔː ʊː/, written a, e, ie, i, o, u, all of

which (with the exception of ie /ɪː/) can be known to represent long vowels in writing only if they are followed by an

orthographic għ or h (otherwise, one needs to know the pronunciation; e.g. nar (fire) is pronounced /na:r/); and

seven diphthongs, /ɐɪ ɐʊ ɛɪ ɛʊ ɪʊ ɔɪ ɔʊ/, written aj or għi, aw or għu, ej or għi, ew, iw, oj, and ow or għu.[40]

Stress[edit]

Stress is generally on the penultimate syllable, unless some other syllable is heavy (has a long vowel or final consonant),

or unless a stress-shifting suffix is added. (Suffixes marking gender, possession, and verbal plurals do not cause the stress

to shift). Historically when vowel a and u were long or stressed they were written as â or û, for example in the

word baħħâr (sailor) to differentiate from baħħar (to sail), but nowadays these accents are mostly omitted.

When two syllables are equally heavy, the penultimate takes the stress, but otherwise the heavier syllable does,

e.g. bajjad [ˈbɐj.jɐt] 'he painted' vs bajjad [bɐj.ˈjɐːt] 'a painter'.

Historical phonology[edit]

Many Classical Arabic consonants underwent mergers and modifications in Maltese:

Classic

ت/t ث/θ ط/tˤ د/d ض/dˤ ذ/ð ظ/ðˤ س/s ص/sˤ ح/ħ خ/χ ع/ʕ غ/ɣ ق/q

al

ه/h/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

Arabic

Maltes

e

/t/

/d/

/s/

/ħ/

/Vː/

/ʔ~k

/

not

pronounc

ed

Orthography[edit]

Alphabet[edit]

Main articles: Maltese alphabet and Maltese Braille

The modern system of Maltese orthography was introduced in 1924.[41] Below is the Maltese alphabet,

with IPA symbols and approximate English pronunciation:

Letter Name

IPA (Alphabet

Name(s))

Maltese

example

IPA

(orthographically

representing)

Approximate English pronunciation

Aa

a

a:

anġlu (angel)

ɐ, a:, æ:

similar to 'u' in nut in RP [a:] similar to father

in Irish English [æ:] similar to cat in American

English, in some dialects it may be [ɒ:] in some

locations as in what in some American English

Dialects

Bb

be

be:

ballun (ball)

b

bar, but at the end of a word it is devoiced

to [p].

Ċċ

ċe

͡

tʃe:

ċavetta (key)

t ͡ʃ

church (note: undotted 'c' has been replaced

by 'k', so when 'c' does appear, it is to be

spoken the same way as 'ċ')

Dd

de

de:

dar (home)

d

day, but at the end of a word it is devoiced

to [t].

Ee

e

e:

envelopp

(envelope)

e:, ɛ, ø:, ə

[e:] somewhat like beet in some English

dialects/French é when long [ɛ] end when

short ,it is often changed to [ø:, œ] when

following and more often when followed by

a w, when at the end in an unstressed syllable

it is pronounced as schwa [ə, Vᵊ] butter

Ff

effe

ɛf(ː)ᵊ

fjura (flower)

f

far

Ġġ

ġe

dʒ͡ ø:

ġelat (ice

cream)

d͡ʒ

gem, but at the end of a word it is devoiced

to [tʃ].

Gg

ge

ge:

gallettina

(biscuit)

ɡ

game, but at the end of a word it is devoiced

to [k].

(ˤ)ː, ħː

has the effect of lengthening

and pharyngealising associated

vowels (għi and għu are [i ̞(ˤ)j] (may be

transcribed as [ə(ˤ)j]) and [oˤ]). When found at

the end of a word or immediately before 'h' it

has the sound of a double 'ħ' (see below).

GĦ

għ

ajn

ajn, æ:n

għasfur (bird)

Hh

akka

ak(:)ɐ

hu (he)

Ħħ

ħe

ħe:, he:, xe:

ħanut (shop)

Ii

i

i:

ikel (food)

not pronounced unless it is at the end of a

word, in which case it has the sound of 'ħ'.

ħ

no English equivalent; sounds similar

to /h/ but is articulated with a lowered larynx.

i ̞:, i:, ɪ

[i ̞:] bite(the way commonly realized in Irish

English or [i:] in other words as beet but more

forward) and when short as [ɪ] bit, occasionally

'i' is used to display il-vokali tal-leħen(the

vowel of the voice) as in words like l-iskola or liMdina ,in this case it takes the schwa sound.

IE ie

ie

i:ᵊ, ɛ:

ieqaf (stop)

ɛ:, iːᵊ

sounds similar to /ie/, as in yield, but opened

up slightly towards /ɛ/ some English dialects

may produce this sound when realizing words

that have ea as in dead or meat

Jj

je

jə, jæ, jɛ

jum (day)

j

yard

Kk

ke

kə, kæ, kɛ

kelb (dog)

k

kettle

Ll

elle

ɛl(:)ᵊ

libsa (dress)

l

line

Mm

emme

ɛm(:)ᵊ

mara (woman) m

march

Nn

enne

ɛn(:)ᵊ

nanna

(granny)

n

next

Oo

o

o:

ors (bear)

o, ɔ, ɒ

[o] as in somewhere between similar to

Scottish English o in no [ɔ] like 'aw' in RP law,

but short or [ɒ] as in water in some American

dialects.

Pp

pe

pe:, pə

paġna (page,

sheet)

p

part

Qq

qe

ʔø, ʔ(ʷ)ɛ,

ʔ(ʷ)æ, ʔ(ʷ)ə

qattus (cat)

ʔ

glottal stop, found in the Cockney English

pronunciation of "bottle" or the phrase "uhoh" /ʔʌʔoʊ/.

Rr

erre

ɛɹ(:)ᵊ, æɹ(:)ᵊ,

ɚ(:)ᵊ or ɛr(:)ᵊ, re (king)

ær(:)ᵊ, ər(:)ᵊ

r, ɹ

[r] as in General American English Butter

,or ɹ road (r realization changes depending on

dialect or location in the word)

Ss

esse

ɛs(:)ᵊ

sliem (peace)

s

sand

Tt

te

te:

tieqa

(window)

t

tired

u, ʉ, ʊ

[u] as in General American English boot or in

some dialects it may be realized as [ʉ] as in

some American English realizations of student,

short u is [ʊ] put

Uu

u

u:, ʉ

uviera (egg

cup)

Vv

ve

vø:, ve:, və

vjola (violet)

v

vast, but at the end of a word it is devoiced

to [f] may be said as [w] in the word Iva(yes)

sometimes this is just written as Iwa.

Ww

ve doppja

/u

doppja/we

vedɒp(:)jɐ,

u:dɒp(:)jɐ,

wø:

widna (ear)

w

west

ʃə, ʃø:

xadina

(monkey)

ʃ/ʒ

shade, sometimes as measure; when doubled

the sound is elongated, as in "Cash shin" vs.

"Cash in".

żraben (shoes)

z

maze, but at the end of a word it is devoiced

to [s].

zalza (sauce)

t͡s / d͡z

pizza

Xx

xe

Żż

że/żeta

Zz

ze

zə, zø:,

ze:t(ɐ)

t͡sə, t͡sø:,

t͡se:t(ɐ)

Final vowels with grave accents (à, è, ì, ò, ù) are also found in some Maltese words of Italian origin, such

as libertà ("freedom"), sigurtà (old Italian: sicurtà, "security"), or soċjetà (Italian: società, "society").

The official rules governing the structure of the Maltese language are found in the official guidebook issued by

the Akkademja tal-Malti, the Academy of the Maltese language, which is named Tagħrif fuq il-Kitba Maltija, that

is, Knowledge on Writing in Maltese. The first edition of this book was printed in 1924 by the Maltese government's

printing press. The rules were further expanded in the 1984 book, iż-Żieda mat-Tagħrif, which focused mainly on the

increasing influence of Romance and English words. In 1992 the Academy issued the Aġġornament tat-Tagħrif fuq ilKitba Maltija, which updated the previous works.[42] All these works were included in a revised and expanded

guidebook published in 1996.[citation needed]

The National Council for the Maltese Language (KNM) is the main regulator of the Maltese language (see Maltese

Language Act, below) and not the Akkademja tal-Malti. However, these orthography rules are still valid and official.

Written Maltese[edit]

Since Maltese evolved after the Italo-Normans ended Arab rule of the islands, a written form of the language was not

developed for a long time after the Arabs' expulsion in the middle of the thirteenth century. Under the rule of

the Knights Hospitaller, both French and Italian were used for official documents and correspondence. During the British

colonial period, the use of English was encouraged through education, with Italian being regarded as the next-most

important language.

In the late eighteenth century and throughout the nineteenth century, philologists and academics such as Mikiel Anton

Vassalli made a concerted effort to standardise written Maltese. Many examples of written Maltese exist from before

this period, always in the Latin alphabet, Il Cantilena being the earliest example of written Maltese. In 1934, Maltese was

recognised as an official language.

Sample[edit]

The Maltese language has a tendency to have both Semitic vocabulary and also vocabulary derived from Romance

languages, primarily Italian. Below are two versions of the same translations, one in vocabulary derived mostly from

Semitic root words while the other uses Romance loanwords (from the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe,

see p. 17):

English

Maltese (Semitic vocabulary)

Maltese (Romance vocabulary)

The Union is founded on the values of

respect for human dignity, freedom,

democracy, equality, the rule of law

and respect for human rights,

including the rights of persons

belonging to minorities. These values

are common to the Member States in

a society in which pluralism, nondiscrimination, tolerance, justice,

solidarity and equality between

women and men prevail.

L-Għaqda hija mibnija fuq is-siwi ta'

għadir għall-ġieħ il-bniedem, ta'

ħelsien, ta' għażil il-ġemgħa, ta'

ndaqs bejn il-ġnus, tas-saltna taddritt* u tal-għadir għall-ħaqq talbniedem, wkoll il-ħaqq ta' wħud li

huma f'minoranzi*. Dan is-siwi

huwa mqassam bejn il-Pajjiżi*

Msieħba, f'nies li tħaddan il-kotrija,

li ma tgħejjibx, li ddann, li tgħaqqad

u li tiżen indaqs in-nisa u l-irġiel.

L-Unjoni hija mibnija fuq il-valuri ta'

rispett għad-dinjità tal-bniedem, ta'

libertà, ta' demokrazija, ta' ugwaljanza,

ta' l-istat tad-dritt u tar-rispett għaddrittijiet tal-bniedem, inklużi d-drittijiet

ta' persuni li jagħmlu parti minn

minoranzi. Dawn il-valuri huma komuni

għall-Istati Membri f'soċjetà

karatterizzata mill-pluraliżmu, in-nondiskriminazzjoni, it-tolleranza, ilġustizzja, is-solidarjetà u l-ugwaljanza

bejn in-nisa u l-irġiel.

*Note: the words dritt (pl. drittijiet), minoranza (pl. minoranzi), pajjiż (pl pajjiżi) are derived

from diritto (right), minoranza (minority) and paese (county) respectively.

Vocabulary[edit]

Although the original vocabulary of the language was Siculo-Arabic, it has incorporated a large number of borrowings

from Romance sources of influence (Sicilian, Italian, and French), and more recently Germanic ones (from English).[43]

The historical source of modern Maltese vocabulary is 52% Italian/Sicilian, 32% Siculo-Arabic, and 6% English, with some

of the remainder being French.[10][44] Today, most function words are Semitic. In this way, it is similar to English, which

is a Germanic language that had large influence from Norman French. As a result of this, Romance language-speakers

may easily be able to comprehend conceptual ideas expressed in Maltese, such as "Ġeografikament, l-Ewropa hi parti

tas-superkontinent ta' l-Ewrasja" (Geographically, Europe is part of the Supercontinent of Eurasia), while not

understanding a single word of a functional sentence such as "Ir-raġel qiegħed fid-dar" (The man is in the house), which

would be easily understood by any Arabic speaker.

Romance[edit]

An analysis of the etymology of the 41,000 words in Aquilina's Maltese-English Dictionary shows that words of Romance

origin make up 52% of the Maltese vocabulary,[10] although other sources claim from as low as 40%,[11] to as high as

55%. This vocabulary tends to deal with more complicated concepts. They are mostly derived from Sicilian and thus

exhibit Sicilian phonetic characteristics, such as /u/ in place of /o/, and /i/ in place

of /e/ (e.g. tiatru not teatro and fidi not fede). Also, as with Old Sicilian, /ʃ/ (English 'sh') is written 'x' and this produces

spellings such as: ambaxxata /ambaʃːaːta/ ('embassy'), xena /ʃeːna/ ('scene' cf. Italian ambasciata, scena).

Maltese

Sicilian

Italian

English

skola

scola

scuola

school

gvern

cuvernu

governo

government

repubblika ripùbblica repubblica republic

re

re

re

cognate:regent; translation: king [45]

natura

natura

natura

nature

pulizija

pulizzìa

polizia

police

ċentru

centru

centro

centre

teatru

tiatru

teatro

theatre

A tendency in modern Maltese is to adopt further influences from English and Italian. Complex Latinate English words

adopted into Maltese are often given Italianate or Sicilianate forms,[10] even if the resulting words do not appear in

either of those languages. For instance, the words "evaluation", "industrial action", and "chemical armaments" become

"evalwazzjoni", "azzjoni industrjali", and "armamenti kimiċi" in Maltese, while the Italian terms are valutazione, vertenza

sindacale, and armi chimiche respectively. English words of Germanic origin are generally preserved relatively

unchanged.

Some impacts of African Romance on Arabic and Berber spoken in the Maghreb are theorised, which may then have

passed into Maltese.[46] For example, in calendar month names, the word furar "February" is only found in the

Maghreb and in Maltese - proving the word's ancient origins. The region also has a form of another Latin named month

in awi/ussu < augustus.[46] This word does not appear to be a loan word through Arabic, and may have been taken over

directly from Late Latin or African Romance.[46] Scholars theorise that a Latin-based system provided forms such

as awi/ussu and furar in African Romance, with the system then mediating Latin/Romance names through Arabic for

some month names during the Islamic period.[47] The same situation exists for Maltese which mediated words

from Italian, and retains both non-Italian forms such as awissu/awwissu and frar, and Italian forms such as april.[47]

Siculo-Arabic[edit]

Siculo-Arabic is the ancestor of the Maltese language,[10] and supplies between 32%[10] and 40%[11] of the language's

vocabulary.

Siculo-Arabic

Maltese

Arabic

English

(in Sicilian)

bebbuxu

babbaluciu

( ببوشbabbūš)

(Moroccan)

snail

ġiebja

gebbia

( جبjabb)

cistern

ġunġlien

giuggiulena

( جنجالنjunjulān)

sesame seed

saqqajja

saia

( ساقيةsāqiyyah)

canal

kenur

tanura

( تنورtannūr)

oven

żagħfran

zaffarana

( زعفرانzaʿfarān)

saffron

żahra

zagara

( زهرةzahrah)

blossom

żbib

zibbibbu

( زبيبzabīb)

raisins

zokk

zuccu

( ساقsāq)

tree trunk

tebut

tabbutu

( تابوتtābūt)

coffin

kapunata caponata

qassata

cassata

(non-Arabic origin)

caponata

savoury pastry pie

Żammit (2000) found that 40% of a sample of 1,821 Quranic Arabic roots were found in Maltese, a lower percentage

than found in Moroccan (58%) and Lebanese Arabic (72%).[48] An analysis of the etymology of the 41,000 words in

Aquilina's Maltese-English Dictionary shows that 32% of the Maltese vocabulary is of Arabic origin,[10] although another

source claims 40%.[11][49] Usually, words expressing basic concepts and ideas, such

as raġel (man), mara (woman), tifel (boy), dar (house), xemx (sun), sajf (summer), are of Arabic origin. Moreover, belles

lettres in Maltese tend to aim mainly at diction belonging to this group.[31]

The Maltese language has merged many of the original Arabic consonants, in particular the emphatic consonants, with

others that are common in European languages. Thus, original Arabic /d/, /ð/, and /dˤ/ all merged into Maltese /d/. The

vowels, however, separated from the three in Arabic (/a i u/) to five, as is more typical of other European languages (/a ɛ

i o u/). Some unstressed short vowels have been elided. The common Arabic greeting as salāmu 'alaykum is cognate

with is-sliem għalikom in Maltese (lit. the peace for you, peace be with you), as are similar greetings in other Semitic

languages (e.g. shalom ʿalekhem in Hebrew).

Since the attested vocabulary of Siculo-Arabic is limited, the following table compares cognates in Maltese and some

other varieties of Arabic (all forms are written phonetically, as in the source):[50]

Negev

Yemenite

Maltese Cairene Damascene Iraqi

Moroccan Modern Standard Arabic English

(bedouin) (Sanaani)

qalb

'alb

'aleb

qalb

galb

galb

qalb

( ق لبqalb)

heart

waqt

wa't

wa'et

—

wagt

wagt

waqt

( وق تwaqt)

time

qamar

'amar

'amar

qamaɣ gumar

gamar

qmar

( ق ممqamar)

moon

kelb

kalb

kaleb

kalb

čalb

kalb

kalb

( ك لبkalb)

dog

English[edit]

It is estimated that English loanwords, which are becoming more commonplace, make up 20% of the Maltese

vocabulary,[11] although other sources claim amounts as low as 6%.[10] This percentage discrepancy is due to the fact

that a number of new English loanwords are sometimes not officially considered part of the Maltese vocabulary; hence,

they are not included in certain dictionaries.[10] Also, English loanwards of Latinate origin are very often Italianised, as

discussed above. English loanwords are generally transliterated, although standard English pronunciation is virtually

always retained. Below are a few examples:

Maltese English

futbol

football

baskitbol basketball

klabb

club

friġġ

fridge

Note "fridge", which is a frequent shortening of "refrigerator", a Latinate word which might be expected to be rendered

as rifriġeratori (Italian uses two different words: frigorifero or refrigeratore).

Grammar[edit]

Maltese grammar is fundamentally derived from Siculo-Arabic, although Romance and English noun pluralisation

patterns are also used on borrowed words.

Adjectives and adverbs[edit]

Adjectives follow nouns. There are no separately formed native adverbs, and word order is fairly flexible. Both nouns

and adjectives of Semitic origin take the definite article (for example, It-tifel il-kbir, lit. "The boy the elder"="The elder

boy"). This rule does not apply to adjectives of Romance origin.

Nouns[edit]

Nouns are pluralised and also have a dual marker. Semitic plurals are complex; if they are regular, they are marked by iet/-ijiet, e.g., art, artijiet "lands (territorial possessions or property)" (cf. Arabic -at and Hebrew -ot/-oth) or -in (cf.

Arabic -īn and Hebrew -im). If irregular, they fall in the pluralis fractus (broken plural) category, in which a word is

pluralised by internal vowel changes: ktieb, kotba " book", "books"; raġel, irġiel "man", "men".

Words of Romance origin are usually pluralised in two manners: addition of -i or -jiet. For

example, lingwa, lingwi "languages", from Sicilian lingua, lingui.

Words of English origin are pluralised by adding either an "-s" or "-jiet", for example, friġġ, friġis from the word fridge.

Some words can be pluralised with either of the suffixes to denote the plural. A few words borrowed from English can

amalgamate both suffixes, like brikksa from the English brick, which can adopt either collective form brikks or the plural

form brikksiet.

Article[edit]

The proclitic il- is the definite article, equivalent to "the" in English and "al-" in Arabic.

The Maltese article becomes l- before or after a vowel.

l-omm (the mother)

rajna l-Papa (we saw the Pope)

il-missier (the father)

The Maltese article assimilates to a following coronal consonant (called konsonanti xemxin "sun consonants"), namely:

Ċ iċ-ċikkulata (the chocolate)

D id-dar (the house)

N in-nar (the fire)

R ir-razzett (the farm)

S is-serrieq (the saw)

T it-tifel (the boy)

X ix-xemx (the sun)

Ż iż-żarbuna (the shoe)

Z iz-zalzett (the sausage)

Maltese il- is coincidentally identical in pronunciation to one of the Italian masculine articles, il. Consequently, many

nouns borrowed from Standard Italian did not change their original article when used in Maltese. Romance vocabulary

taken from Sicilian did change where the Sicilian articles u and a, before a consonant, are used. In spite of its Romance

appearance, il- is related to the Arabic article al-.[citation needed]

Verbs[edit]

Verbs show a triliteral Semitic pattern, in which a verb is conjugated with prefixes, suffixes, and infixes (for

example ktibna, Arabic katabna, Hebrew kathabhnu (Modern Hebrew: katavnu) "we wrote"). There are two tenses:

present and perfect. The Maltese verb system incorporates Romance verbs and adds Maltese suffixes and prefixes to

them (for example, iddeċidejna "we decided" ← (i)ddeċieda "decide", a Romance verb + -ejna, a Maltese first person

plural perfect marker).