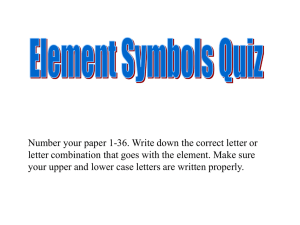

Oral Zinc for the Treatment of Acute Gastroenteritis in Polish Children: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial Bernadeta Patro, MD, Henryk Szymański, MD, and Hania Szajewska, MD Objective To evaluate the efficacy and safety of zinc in the treatment of acute gastroenteritis (AGE) in children in Poland. Study design Children aged 3 to 48 months with AGE were enrolled in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which they received zinc sulfate (10 or 20 mg/day depending on age) or placebo for 10 days. A total of 141 of 160 children recruited were available for intention-to-treat analysis. The primary outcome was the duration of diarrhea. Results In the experimental group (n = 69) compared with the control group (n = 72), there was no significant difference in the duration of diarrhea (P > .05). Similarly, there was no significant difference in the groups in secondary outcome measures such as stool frequency on days 1, 2, and 3, vomiting frequency, intravenous fluid intake, and the number of children with diarrhea lasting >7 days. Conclusion Children living in a country where zinc deficiency is rare do not appear to benefit from the use of zinc in the treatment of AGE. (J Pediatr 2010;157:984-8). T he morbidity and mortality rates from acute diarrhea remain significant in children <5 years of age, especially those in developing countries.1 In the developed world, although the mortality rate is low, gastroenteritis leads to a high number of physician visits, hospital admissions, and consequently, a significant economic burden. It is estimated that the incidence of diarrhea in European children up to 3 years of age ranges from 0.5 to 1.9 episodes per child per year.2 Most cases of acute gastroenteritis (AGE) are usually mild and self-limited. Oral or intravenous re-hydration is used as the first-line therapy. Although this elementary approach is effective in substantially reducing morbidity and mortality rates, new treatment options are required to address the severity and duration of the symptoms. The administration of zinc appears to be such an option. The mechanisms underlying the beneficial anti-diarrheal effect of zinc are unclear. In brief, plausible mechanisms include improved absorption of water and electrolytes by the intestine, faster regeneration of gut epithelium, increased levels of enterocyte brushborder enzymes, and an enhanced immune response.3 However, it is questionable whether administered zinc can exert its actions independent of zinc deficiency in the host. A number of randomized controlled trials performed in developing countries have shown that zinc supplementation is effective in reducing the duration and severity of diarrhea. On the basis of these findings, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organization (WHO) currently recommend zinc supplementation as a universal treatment for all children with AGE.4 However, according to the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition/European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases (ESPGHAN/ESPID) recommendations, there is not enough evidence to support its routine use in children with AGE living in Europe, where zinc deficiency is rare.2 Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of zinc supplementation in the treatment of AGE in a different clinical population and setting (ie, in well-nourished, otherwise healthy children living in Poland). Methods This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted at 2 pediatric hospitals in Poland. Candidates for inclusion in the study were children 3 to 48 months of age who were diagnosed with AGE lasting less than 5 days but with at least some degree of dehydration; they had either been admitted to the hospital or visited the hospital emergency ward as an outpatient. Children were excluded from the study when any of these criteria were present: diarrhea lasting <1 day or >5 days, recent history of diarrhea (last 2 weeks before enrollment day), chronic gastrointestinal disease with diarrheal manifestation AGE ESPGHAN/ESPID HDI RCT UNICEF WHO Acute gastroenteritis European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition/European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases Human Development Index Randomized controlled trial United Nations Children’s Fund World Health Organization From the Department of Paediatrics, The Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland (B.P., H. Szajewska); and Department of Paediatrics, St Hedwig of Silesia Hospital, Trzebnica, Poland (H. Szymański) Supported in part by the Nutricia Research Foundation. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. 0022-3476/$ - see front matter. Copyright Ó 2010 Mosby Inc. All rights reserved. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.05.049 984 Vol. 157, No. 6 December 2010 (eg, food allergy, celiac disease), weight-to-height ratio <5th percentile, severe dehydration, coexistence of serious systemic disease(s), administration of antibiotics (during current infection), exclusive or >50% breastfeeding, history of immunodeficiency, and administration of immunosuppressive therapy. Parents provided informed consent for all study participants. The Ethical Committee at the Medical University of Warsaw approved the study. All children eligible for recruitment were assessed for the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The physician examined each child, and the hydration status was evaluated (as defined by the method of WHO).5 Nude body weight and height were recorded, and the nutritional status was assessed with weight-forage, height-for-age, and weight-height ratio percentiles. Stool samples were collected to investigate the etiology of the diarrhea. Tests performed included bacteriological culture to detect bacterial pathogens (Salmonella spp, Shigella spp, Escherichia coli) and chromatographic immunoassay (VIKIA Rota-Adeno; BioMerieux, Lyon, France) to detect rotaviruses and adenoviruses. Dehydration was managed according to ESPGHAN/ESPID2 and WHO guidelines.5 After re-hydration, early refeeding with the patient’s usual diet was practiced. Patients were assigned randomly to receive either placebo or zinc sulfate at a dose of 10 mg (for patients <6 months of age) or 20 mg (for children >6 months) daily, in 2 doses, for 10 days. Zinc was supplied as a syrup containing 2 mg of zinc in 1 mL of sirupus simplex; sirupus simplex is a solution of 64 parts of saccharose in 36 parts of purified water. The placebo was identically supplied and formulated. There was no difference between zinc and the placebo in appearance; a minor metallic aftertaste of zinc was hardly detectable. The study products were provided by the pharmacy department in the hospital in Warsaw for both centers. The syrup was offered between meals to prevent the negative influence of some dietary factors on absorption.6 Each parent of an included child received a diary to record the number and consistency of stools and to specify the time of the day (1-hour period) when the stool was passed. They were also asked to record any vomiting episodes and any other symptoms that they considered to be important or to represent an adverse event. Children were examined by the physician every day until they were discharged from the hospital. Discharged children and outpatients were followed up with hospital visits or with daily telephone calls, depending on the patient’s condition and the parents’ decision. Treatment compliance was assessed with direct interview of the parents and review of the diary cards. Randomization Two different randomization lists for each center were computer-generated by an investigator at the Medical University of Warsaw. Block randomization of block size 6 was done. The glass bottles containing the products were labeled with the patient’s number corresponding to the randomization list by an independent individual who was not involved in patient enrollment. Randomization codes were secured until the completion of data collection and initial analysis. All investigators, participants, outcome assessors, and data analysts were blinded to the assigned treatment for the duration of the study. Primary and Secondary Outcome Measures The primary outcome measure was the duration of diarrhea. Diarrhea was defined as the passage of $3 loose stools in a 24-hour period. The duration of diarrhea was defined as the time from administration of zinc/placebo to the cessation of diarrhea (the passage of 2 formed stools or no stool for 12 hours on the last day meeting the criteria for diarrhea). Secondary outcome measures were stool frequency on days 1, 2, and 3, vomiting frequency on days 1, 2, and 3, total intravenous fluid intake, the number of children with diarrhea lasting >7 days, and adverse events. Sample Size The sample size was calculated on the basis of the assumption that a 1-day reduction in the primary outcome measure (diarrhea duration) would be a clinically important difference in the study groups. We estimated that with a power of 80%, an a level of 0.05, and a 20% dropout rate, 160 children would be required. Statistical Methods The statistical analyses were conducted with StatsDirect software version 2.7.7 (StatsDirect Ltd., Altrincham, United Kingdom). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the means of continuous variables because of their non-normal distribution. The Shapiro-Wilk W test was used to investigate a sample for evidence of ‘‘non-normality.’’ Proportions were compared with the Fisher exact test. The difference in study groups was considered significant when the P value was <.05. All statistical tests were 2-tailed and performed at the 5% level of significance. We analyzed the results of this study on the basis of intention to treat. Results We enrolled 160 children from a group of 249 eligible patients between February 2008 and December 2009. The main reason for exclusion at this stage of the study was lack of parental consent. The Figure (available at www.jpeds.com) shows the flow of participants through each stage of the study. Eighty-one children were assigned to the zinc group, and 79 children were assigned to the placebo group. Four patients in the experimental group and 3 patients in the control group did not receive the allocated intervention because of their parents’ decision and refusal to drink, respectively. Nine patients in the zinc group and 8 patients in the placebo group discontinued the intervention because of refusal to drink and parents’ decision. Most of these parents decided not to continue administration of the syrup because the symptoms of diarrhea had ceased. Nineteen patients 985 THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS www.jpeds.com (11.8%) were lost to follow-up (12 in the zinc group and 7 in the placebo group), thus data from 141 patients were available for the intention-to-treat analysis. The baseline characteristics of the enrolled children are detailed in Table I. In approximately half the cases (47%), a viral etiology of AGE was confirmed. Rotavirus was the leading pathogen responsible for 43% of the cases of diarrhea. A bacterial etiology was confirmed in 10.6% of the patients. Only 12.5% of all participants were outpatients seeking help at the hospital emergency ward; most participants (87.5%) were inpatients. The outcome measures are summarized in Table II. The median duration of diarrhea was 58 hours in the zinc group, compared with 39 hours in the placebo group. No significant difference was observed in the groups (P > .05). The proportion of children with diarrhea lasting >7 days was slightly higher in the control group (4.2% versus 1.4%), but the difference in groups was not statistically significant. Zinc administration did not influence the severity of the diarrhea measured as stool frequency. There were no differences in the groups in the number of bowel movements on days 1, 2, and 3. Similarly, there was no significant difference in vomiting frequency or total intravenous fluid intake in the groups. Adverse Events The proportions of patients who experienced any adverse event were similar in the zinc and placebo groups: 5 (6.1%) of 81 patients and 6 (7.5%) of 79 patients, respectively. Abdominal pain, cough, rash, and vomiting after administration of the syrup were reported in both groups at similar frequencies. Only 1 patient in the zinc group reported an ab- Table I. Baseline characteristics of the study children Mean (SD) age, months Sex (female/male) Body weight (SD), kg Breastfed (%) Dehydration Mild (%) Moderate (%) Need for intravenous fluids at enrollment (%) Fever >38.0 Co (%) Vomiting (%) Diarrhea before enrollment (SD), days Number of stools 24 hours before enrollment (SD) Blood in stool (%) Etiology Rotavirus (%) Adenovirus (%) Salmonella (%) E coli (%) Shigella (%) Setting Hospital (%) Outpatient (%) 986 Placebo n = 79 Zinc n = 81 20.8 (11.4) 1.4 11.3 (2.9) 12 (15.2) 22.3 (12.6) 1.0 11.4 (2.8) 13 (16.0) 63 (80) 16 (20) 67 (85) 59 (73) 22 (27) 60 (74) 46 (58.2) 64 (81) 2.3 (1.2) 6.5 (3.9) 44 (54.3) 66 (81.5) 2.0 (1.1) 7.6 (4.7) 8 (10.1) 8 (9.9) 30 (38.0) 4 (5.0) 7 (8.9) 1 (1.3) 39 (48.1) 2 (2.5) 7 (8.6) 2 (2.5) - 72 (91.1) 7 (8.9) 68 (84.0) 13 (16.0) Vol. 157, No. 6 normal aftertaste associated with the administration of the syrup. No severe adverse events were observed. Discussion In our study, zinc supplementation of young children with AGE had no beneficial effect on diarrhea duration or severity. The proportion of children who experienced diarrhea lasting >7 days was similar in both groups. Zinc therapy was well tolerated, and it was not associated with an increased frequency of vomiting. The results of our study are inconsistent with the results of previously conducted studies, subsequent systematic reviews, and meta-analyses7-10 that have shown an anti-diarrheal effect of zinc in children <5 years of age. This beneficial effect of zinc was mainly associated with diarrhea duration. Furthermore, all the conducted studies were performed in countries with a medium (India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Nepal, Brazil, Turkey, Pakistan, Egypt, Philippines) or low (Ethiopia) Human Development Index (HDI11; assessed at the time when the study was performed), where malnutrition and zinc deficiency are important problems.12 No studies that assessed the effects of zinc for the treatment of AGE in children <5 years of age were performed in a country with a high or very high HDI, an index considered to be a standard means of measuring well-being, especially child welfare, where zinc deficiency is rare. However, in several randomized controlled trials (RCTs),13-17 no advantageous effect of zinc therapy on diarrhea duration or severity was observed, or an observed effect was not statistically significant. The common feature of these studies is the sufficient zinc status of the participants (ie, exclusively well-nourished participants17; infants <6 months of age likely to have adequate total body zinc acquired in utero15,16; subjects with normal serum zinc levels13,14). Although we do not have precise data, on the basis of available indicators of risk of zinc deficiency (eg, the percentage of the population at risk for inadequate zinc intake), we can conclude that Polish children are also not a population at high risk of zinc deficiency.12 This observation supports the hypothesis that the anti-diarrheal effect of zinc is dependent on zinc deficiency. The other aspect to consider is whether zinc is equally effective against all types of infectious diarrhea or whether its action is pathogen specific. Available data on the etiology of the diarrhea from earlier studies are limited. Authors of only a few RCTs13,14,18-21 performed diagnostic microbiology. In our study, a viral pathogen (mainly rotavirus) was identified in approximately half the patients with AGE. Our results are inconsistent with the results of the study by Bhatnagar et al, in which the proportion of viral infection was comparable. We investigated the efficacy of zinc administration in a different clinical setting. Our population consisted of young children with diarrhea who were living in Europe, where Patro, Szymański, and Szajewska ORIGINAL ARTICLES December 2010 Table II. Outcome measures Outcome measure Diarrhea duration in hours, median (range) Stool frequency (n/day), median (range) Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Vomiting frequency (n/day), median (range) Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Total intravenous fluid intake (mL/kg), median (range) Diarrheal episodes lasting >7 days, n (%) Placebo n = 72 Zinc n = 69 Effect size (95% CI) P value* 39 (12-196) 58 (12-187) Median difference 4 (–5-18) .33 4 (0-38) 3 (0-14) 2 (0-13) 5 (0-20) 3 (0-17) 2 (0-10) 1 (0-2) 0 (0-1) 0 (0-1) .13 .30 .31 0 (0-4) 0 (0-3) 0 (0-10) 72 (0-318) 3 (4.2) 0 (0-7) 0 (0-4) 0 (0-5) 73 (0-425) 1 (1.4) 0 (0-0) 0 (0-0) 0 (0-0) 0 (–33-12) Relative risk 0.35 (0.04-3.26) .68 .37 .91 .48 .61 *Mann-Whitney test or Fisher exact test (as appropriate). the major problem is diarrhea frequency and the associated economic burden. Contrary to other studies, this RCT was performed in a country with a high HDI. The participants were well-nourished, otherwise healthy children who were, therefore, unlikely to be zinc deficient. The dose of zinc and duration of treatment were in accordance with the WHO recommendations.4 We chose an adequate study design and made some efforts to avoid systematic bias (eg, proper generation of the random allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding). The major potential limitation of this trial is the relatively high percentage of patients either lost to follow-up or who discontinued the intervention. However, the noncompliance rate tended to increase with recovery from the diarrhea. All available data were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. Also, we cannot exclude the potential risk of poor adherence associated with using diaries to record measured outcomes (mainly during the period after discharge and in outpatients). To minimize this risk, direct interview of the parents was undertaken. We did not evaluate serum zinc levels to estimate the risk of zinc deficiency in the enrolled patients. To our knowledge, currently there are no sufficiently sensitive biomarkers of individual zinc status to identify mild to moderate zinc deficiency.12 Because most of our patients (87.5%) were admitted to the hospital, we cannot rule out a different pattern of response to treatment in a fully outpatient setting. Despite the growing number of studies evaluating zinc supplementation for the treatment of AGE in children, there are still some questions to be answered in the areas of basic and applied research. The results of our study did not confirm that zinc supplementation is effective in the treatment of AGE in a country in which zinc deficiency it not a problem. However, our findings are not in opposition to the results of earlier studies that have indicated beneficial effects of administered zinc in populations in which malnutrition is common. However, the recommendations of UNICEF and WHO on zinc supplementation as a universal treatment for diarrhea in these populations cannot be simply extrapolated to all children from devel- oped countries; rather, in line with the ESPGHAN/ESPID recommendations, the UNICEF and WHO recommendations should apply to any malnourished child. n Submitted for publication Mar 3, 2010; last revision received Apr 14, 2010; accepted May 26, 2010. Reprint requests: Bernadeta Patro, MD, Department of Paediatrics, The Medical University of Warsaw, 01-184 Warsaw, Dzialdowska 1, Poland. E-mail: abpatro@yahoo.com. References 1. Bryce J, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, Black RE. WHO Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group. WHO estimates of the causes of death in children. Lancet 2005;365:1147-52. 2. Guarino A, Albano F, Ashkenazi S, Gendrel D, Hoekstra JH, Shamir R, et al., Expert Working Group. The ESPGHAN/ESPID evidenced-based guidelines for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children in Europe. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2008;46(Suppl 2):S81-122. 3. Hoque KM, Binder HJ. Zinc in the treatment of acute diarrhea: current status and assessment. Gastroenterology 2006;130:2201-5. 4. WHO/UNICEF joint statement: clinical management of acute diarrhea. New York, NY, and Geneva, Switzerland: The United Nations Children’s Found/WHO; 2004. 5. World Health Organization. The treatment of diarrhoea: a manual for physicians and other senior health workers (4th revision). 2005. Available at: http://www.who.int/child_adolescent_health/documents/9241593180/ en/index.html. Accessed January 2010. 6. Lönnerdal B. Dietary factors influencing zinc absorption. J Nutr 2000; 130(5S Suppl):1378-83. 7. Zinc Investigators’ Collaborative Group. Therapeutic effects of oral zinc in acute and persistent diarrhea in children in developing countries: pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 72:1516-22. 8. Lukacik M, Thomas RL, Aranda JV. A meta-analysis of the effects of oral zinc in the treatment of acute and persistent diarrhea. Pediatrics 2008; 121:326-36. 9. Patro B, Golicki D, Szajewska H. Meta-analysis: zinc supplementation for acute gastroenteritis in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28: 713-23. 10. Lazzerini M, Ronfani L. Oral zinc for treating diarrhoea in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;3:CD005436. 11. Human Development Reports. Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/ statistics/. Accessed February 2010. 12. International Zinc Nutrition Consultative GroupHotz C, Brown KH. International Zinc Nutrition Consultative Group technical document #1. Oral Zinc for the Treatment of Acute Gastroenteritis in Polish Children: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial 987 THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS 13. 14. 15. 16. 988 www.jpeds.com Assessment of the risk of zinc deficiency in populations and options for its control. Food Nutr Bull 2004;25(Suppl 2):S99-203. Sachdev HPS, Mittal NK, Mittal SK, Yadav HS. A controlled trial on utility of oral zinc supplementation in acute dehydrating diarrhea in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1988;7:877-81. Roy SK, Tomkins AM, Akramuzzaman SM, Behrens RH, Haider R, Mahalanabis D, et al. Randomised controlled trial of zinc supplementation in malnourished Bangladeshi children with acute diarrhoea. Arch Dis Child 1997;77:196-200. Brooks WA, Santosham M, Roy SK, Faruque AS, Wahed MA, Nahar K, et al. Efficacy of zinc in young infants with acute watery diarrhea. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:605-10. Fischer Walker CL, Bhutta ZA, Bhandari N, Teka T, Shahid F, Taneja S, et al. Zinc Study Group. Zinc supplementation for the treatment of diarrhea in infants in Pakistan, India and Ethiopia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2006;43:357-63. Vol. 157, No. 6 17. Boran P, Tokuc G, Vagas E, Oktem S, Gokduman MK. Impact of zinc supplementation in children with acute diarrhoea in Turkey. Arch Dis Child 2006;91:296-9. 18. Dutta P, Mitra U, Datta A, Niyogi SK, Dutta S, Manna B, et al. Impact of zinc supplementation in malnourished children with acute watery diarrhoea. J Trop Pediatr 2000;46:259-63. 19. Al-Sonboli N, Gurgel RQ, Shenkin A, Hart CA, Cuevas LE. Zinc supplementation in Brazilian children with acute diarrhoea. Ann Trop Paediatr 2003;3:3-8. 20. Bhatnagar S, Bahl R, Sharma PK, Kumar GT, Saxena SK, Bhan MK. Zinc with oral rehydration therapy reduces stool output and duration of diarrhea in hospitalized children: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2004;38. 340–40. 21. Roy SK, Raqib R, Khatun W, Azim T, Chowdhury R, Fuchs GJ, et al. Zinc supplementation in the management of shigellosis in malnourished children in Bangladesh. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008;62:849-55. Patro, Szymański, and Szajewska ORIGINAL ARTICLES December 2010 Assessed for eligibility n=249 Excluded n=105 Enrollment Reason: not meeting inclusion criteria refused to participate Randomized n=160 Allocated to placebo group n=79 Received allocated intervention n= 76 Allocation Did not receive allocated intervention n=3 Reason: refused to drink syrup Lost to follow-up n= 7 Reason: parent’s decision, technical difficulties Discontinued intervention n=8 Reason: refused to drink syrup, parent’s decision Did not receive allocated intervention n=4 Reason: parent’s decision Follow-Up Analyzed n=72 Excluded from analysis n=7 Reason: lost to follow-up Allocated to zinc group n=81 Received allocated intervention n= 77 Lost to follow-up n= 12 Reason: parent’s decision, technical difficulties Discontinued intervention n= 9 Reason: refused to drink syrup, parent’s decision Analyzed n=69 Analysis Excluded from analysis n=12 Reason: lost to follow-up Figure. Flow diagram of the progress of patients through the study. Oral Zinc for the Treatment of Acute Gastroenteritis in Polish Children: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial 988.e1