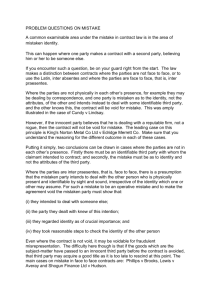

Unilateral Mistake in Contract Law: Inter Praesentes vs. Inter Absentes

advertisement

‘The distinction between inter preaesentes (Face to Face) and inter absentes (distance/correspondence) unilateral mistake is illogical in the modern era.’ In this essay, We explain the doctrine of Unilateral mistake holistically further in more specific terms in inter preasentes and inter absentes, Cases of both face to face and correspondence will proof that judges outcomes are not consistence and that it could not create certainty in the eyes of the law and us who walk under it .Furthermore we will attempt in this essay to illustrate these inconsistencies and what effect this has now in the modern era. The main problem is the distinction drawn between inter preasentes and inter absentes Inter absentes: Parties are not physically present when the contract is made e.g., where the contract is made by telephone dealing over the internet and by post, the courts will only find a mistake if the claimant con demonstrate an identifiable person or business with whom they intended to deal with. A mistake to their attributes will not suffice. Inter Praesentes: Parties contract face to face contractual transaction that raises a presumption that the parties intend to deal with the person in front of him. Unilateral Mistake is relied upon where there is a mistake to identity of one of the contracting parties ,a mistake of this nature ,where the identity of one parties is of fundamental importance will render the contract void ab intio, The law has drawn a fine line distinction between where a person intended to contract with someone else, this in turns mean the contract is rendered void and a mistake only on the persons attributes rather than his identity for example his creditworthiness, can lead the contract intact. Leading case that has both Face to face dealing (inter praesentes) and through distance (inter absentes) is: Shogun Finance Ltd v Hudson (2003) this case illustrates the diversity in decisions made by the courts, generally a majority vote is seen as a weak judgment for law compared to unanimous decisions which creates certainty and clarity of court’s decision. In this case Mr. Patel (rogue) wanted to buy on hire purchase a car from a dealer (agent) meeting was done face to face in which documentation of Mr. Patel was asked (agent)and then send to(distance/correspondence) Shogun Finance to check his credit worthiness (attribute) which was confirmed that he was cleared for the hire purchase. It was held at court (3:2) The majority of the House of Lords (Lord Hobhouse. Lord Phillips and Lord Walker) that there was no contract (rescission) of hire purchase between the rogue and Shogun finance and that the car was not Mr. Hudson’s, this followed principle can be seen in Cundy v Lindsay, that written agreements do not infer a presumption to sell to the immediate possible purchaser where their identity is a key factor of importance to create a contract. However, judges who were in dissent argued that the distinction is irrational and should be discarded, the presumption of all cases should be that the contract is only voidable and not void. Unilateral mistake and basic principles of offer and acceptance, here the House of lords relied heavily on Shogun finance offer to sell the car on credit terms to Mr. Patel this Shoguns offer is only for Mr. Patel there for a 3rd party cannot accept the offer however the problem from the minority opinion the innocent 3rd party is at a huge financial risk. In Cundy v Lindsay, the contract was held void because plaintiff only intended to contract with the person named in the correspondence (inter absentes) and knew of a company dealing under the name assumed by the rogue, Lord Cairns: ‘of Blenkarn the plaintiff knew nothing and of him they never thought, with him they never intended to deal. Their minds never, even of an instant of time, rested upon him, and as between him and them there was no consensus of the mind which could lead to any arrangement or any contract whatsoever’’. Contradicting case (inter absentes) In King’s Norton Metal v Edrige, plaintiff was held to intend to contract with the writer however note that mistake to identity, rather than attributes of the rogue, here was a mistake of creditworthiness of the rogue and of the letter and there existed no other entity of the assumed name. The contract stayed intact (voidable) not void. Cases in Face to Face dealing (inter preasentes) In this case Phillips v Brooks Ltd (1919) (inter preasentes) a rogue presented himself as Sir George Bullough in a jewelry shop, he also stated that he resided at St James square Phillips then checked the telephone directory to check if he lives there, and so allowed the rogue to take the ring but not the pearl necklace until the cheque had cleared, which it did not, the rogue sold off the ring to an innocent 3rd party Brooks Ltd. It was held the contract was not void between the Rogue and Phillips. Phillips had intended to contract with the man in his shop no matter his identity. Justice Horridge: ‘’ It is quite true the plaintiff in re-examination said he had no intention of making any contract with any other person than Sir George Bullough, but I think, I have to decide what is the proper inference to draw where a verbal contract is made, and an article delivered to an individual describing himself as somebody else’’. In the case of Lewis v Averay (1972) (inter preasentes) a rogue presented himself as a famous actor Richard Greene and wanted to buy the car from the plaintiff with a cheque of 450 pounds the plaintiff was reluctant to let him have the car until the cheque was cleared further more the plaintiff asked for proof of identity and the rogue gave a pass of entrance to Pinewood Studios, which on the entrance pass the name and photograph of Richard Greene was visible and that person was standing in front of him. It was held by the court that the contract was not void. Lord Denning MR. agree with the decision but on the basis that mistake as to identity should only ever make a contract voidable, and not void. ‘’As I listened to the argument in this case, I felt it wrong that an innocent purchaser who knew nothing of what passed between the seller and the rogue, should have his title depend on such refinements. After all, he was acted with complete circumspection’’. Contradicting case (inter preasentes) In the case of Ingram v Little (1961) a rogue fraudulently introduced himself as P.G.M. Hutchinson residing at a specified address two elderly ladies the owner of a car who sold the car to the rogue who paid by cheque, the ladies looked through the telephone directory to see if Mr. Hutchinson really lives in that address. It was held that the contract was void the owners only real intention was to deal with the real Mr. Hutchinson. Nemo dat quod non habet to Lewis. Who should bear the risk? the original seller or the downstream purchaser (3rd party) better position to bear the loss? It seems that most of the court of appeal agreed that the old ladies should not bear the risk and the 3rd party should. In shogun, the minority expressed the view (Lord Nichols and Lord Millet), that ‘’new means of communications render the distinction untenable, the majority, however, whilst recognizing the problem, did not address its unwanted side effect and re-affirmed the distinction. In our present age what category does instant messages face to face or correspondence? What category does a video call fall under? If the use of text-based communication prevents the assumption arising it must be concluded that e-commerce transaction is tainted by mistake of identity of the party can only be voidable not void as you can see it is extremely easy currently to show with more examples the absurdity of the distinction. In conclusion I would like to add and stipulate the need for a change of the distinction, it is irrelevant in our modern era and the courts should address this issue of distinction inter (preasentes & inter absentes) which I find at this present age ‘’not relevant.’’