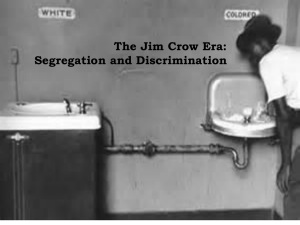

Kaylee Hoffman The great hope that was brought about in 1866 by the passing of the 14th Amendment, which promises that all citizens of the United States regardless of their race, ethnicity, or color would have “equal protection under the law”, would quickly disappear as it proved unable to protect and equalize African-Americans. Instead, blacks were stripped of their right to vote through crafty laws like the “grandfather clause”. They were barred from jobs, stores, neighborhoods, parks, and restaurants. Black men were lynched by violent mobs for no other crime than that of existing. Such was the situation of blacks in the Jim Crow South, a land of social and political segregation. Black leaders had to devise ideas on how to move forward and achieve social, political, and economic advancement. But they often disagreed with each other on how to accomplish this. Booker T. Washington, a former slave himself and co-founder of the Tuskegee Institute, gave a speech in 1896 at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta that would soon come to be known as “The Atlanta Compromise’. In this speech, he advocated for the slow advancement of Blacks in society by earning the respect of their white neighbors through their industrial workings, believing that an economic advancement would be followed by a social and political one. W.E.B DU Bois, the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard and one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), wrote an essay in 1903 titled “The Souls of Black Folk” which criticized Washington’s ideas as justifying segregation and the denial of black rights. The one, though, who had better ideas in making progress against racism was W.E.B Du Bois because unlike Booker T. Washington, DU Bois recognized that the only way to achieve social and political equality was through fighting for their political and civil rights. 1 First of all, DU Bois understood that it would be very difficult, if not impossible, for black to gain economic advancement if they did not first achieve political and social advancement. He said, “Is it possible, and probable, that nine millions of men can make effective progress in economic lines if they are deprived of political rights, made a servile caste, and allowed only the most meagre chance for developing their exceptional men? If history and reason give any distinct answer to these questions, it is an emphatic No.” How can one become economically prosperous, when they can only work in low paying jobs? And even when they did attain economic prosperity, how could they protect themselves from losing it all by jealous neighbors when they have no legal means to do so. It is vital that political rights are secured if economic rights are to be. Washington, though, did not seem to understand this. Instead, he says that while “it is important and right that all privileges of the law be ours… it is vastly more important that we be prepared for the exercise of these privileges”. Secondly, Washington assumed that if blacks could gain the respect of white southerners then they would also gain social and political equality. He stated, “No race that has anything to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized”. But does not the almost 250 year existence of slavery in America contradict that fact? Throughout this whole time African-Americans had proven their ability to “contribute to the markets of the world”, yet their slavery and ostracization only grew stronger. DU Bois, on the other hand, realized that “the way for a people to gain their reasonable rights is not by voluntarily throwing them away and insisting and anisistinging they do not want them” instead they must” insist continually, in season and out of season, that voting is necessary”. Third, Washington seems to agree with segregation by saying that “in all things purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual 2 progress”. Now Washington might have said this in order to ensure that his ideas would not be rejected for its “radicalism” but when concessions are made it becomes all the more harder to gain them back. DU Bois, however, is careful to make no distinction between the social and economic. Neither does he attempt to ignore the injustice of the South. Instead he says that they must “assert her better self and do her full duty to the race she has cruelly wronged and is still wronging”. In conclusion, then W.E.B. DU Bois’s ideas were better in making progress against racism because he emphasized the importance of gaining social and political rights, not just economic rights. This is not because Washington’s ideas were bad ones, indeed they are a great stepping stone, it is merely that he did not seem to recognize that liberty and equality do not come to you unless you fight for them as hard as you possibly can. DU Bois recognizes this and finishes off his essay with these words: “By every civilized and peaceful method we must strive for the rights which the world accords to men, clinging unwaveringly to those great words ethic the sons of the Fathers would fain forget: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’”. It is this very sentiment that would fuel Martin Luther King Jr. over 50 years later to lead the movement that would finally fulfill the promise of the 14th Amendment. 3