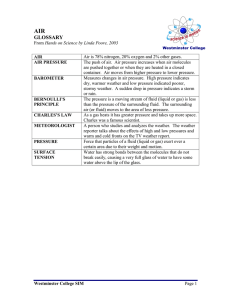

Keeping electrolytes and fluids in balance, part 1 Keeping electrolytes & fluids in part 1 The “critical care shuffle” of abnormalities can threaten patient outcomes. Find out how to respond. C By Alicia L. Culleiton, DNP, RN, CNE, and Lynn C. Simko, PhD, RN, CCRN Critically ill patients are diverse in terms of illness, but many experience electrolyte abnormalities or fluid imbalances that can compromise their clinical status and adversely affect outcomes. These shifts in electrolytes and fluids—the “critical care shuffle”—can be attributed to an underlying chronic disease state, an acute condition that manifests during the course of the patient’s hospitalization, or the administration of certain medications. Monitoring and carefully managing electrolytes and fluid balance is an integral part of assessing and caring for a critically ill patient. This series provides a general overview of the electrolytes tested and I.V. fluids used in critical care areas, as well as the common causes, signs and symptoms, and available treatments to correct electrolyte abnormalities and fluid imbalances. This article describes sodium and fluid imbalances. A later article will describe imbalances in potassium, calcium, and magnesium. The balancing act Fluid and electrolyte balance play an important role in homeostasis, and critical care nurses assume a vital role in identifying and treating the physiologic 30 l Nursing2011Critical Care l Volume 6, Number 2 stressors experienced by critically ill patients that disrupt homeostasis.1 Electrolytes, found in body fluids, are electrically charged particles (ions). Cations are positively charged ions; anions are negatively charged ions. Electrolytes play a crucial role in transmitting impulses for proper heart, nerve, and muscle function. The number of positively and negatively charged ions should be equal; when this balance is upset, electrolyte abnormalities can occur. Electrolytes can further be classified as extracellular (EC, outside the cell) or intracellular (IC, inside the cell). Sodium is the most abundant EC electrolyte; potassium is the most abundant IC electrolyte. Just as too little or too much of any one electrolyte can become a problem in maintaining a critically ill patient’s stability, imbalances in fluid homeostasis can also present unique challenges for both you and your patient. Fluids are in constant motion in the body. Total body water (TBW) normally accounts for about 60% of an adult’s body weight. Forty percent of TBW is in the IC space, and EC water accounts for 20% of body weight: 14% in the interstitial space, www.nursing2011criticalcare.com Copyright © 2011 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. ©ISTOCKPHOTO.COM/WINTERLING Downloaded from https://journals.lww.com/nursingcriticalcare by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC4/OAVpDDa8KKGKV0Ymy+78= on 12/29/2020 balance www.nursing2011criticalcare.com doesn’t support the numbers, perform a follow-up test—an error could have occurred in the lab, blood draw, or be the result of blood sample hemolysis. Now let’s look more closely at sodium and fluid balance. Sodium: Water follows Sodium is the key EC cation and plays a major role in serum osmolality. When serum sodium levels change, so does serum osmolality and water movement. Normally, serum osmolality is 280 to 300 mOsm/kg; the value is considered critically abnormal if it’s 240 mOsm/kg or lower, or 320 mOsm/kg or higher.5 Sodium also is a primary contributor to nerve impulse transmission and muscle contraction. If you suspect that your critically ill patient has a sodium imbalance, think of water, and specifically, disorders of water balance. Remember the saying, “where sodium goes, water is sure to follow.” In the simplest of terms, sodium in the body is accompanied by water. Although serum sodium levels often reflect changes in water balance, the body’s sodium concentration may be increased, decreased, or normal, so the patient’s volume status must also be evaluated before beginning treatment.1,6 Hypotonic (dilutional) hyponatremia is the most common type of hyponatremia, and can further be classified as hypovolemic, isovolemic (euvolemic), or hypervolemic based on the accompanying EC fluid volumes.2 How body water is distributed2 The graphic shows the approximate size of body compartments in a 154.3-pound (70 kg) adult. Total body water = 60% body weight 14% 200 28 liters 100 Interstitial 10 liters 5% 1% Transcellular 1 liter 300 Extracellular water 20% body weight Plasma 3.5 liters Intracellular water 40% body weight Osmolarity - mOsm/L and 5% in the intravascular space. Transcellular fluid (cerebral spinal fluid and fluid contained in other body spaces such as joint spaces, and the pleural, peritoneal, and pericardial spaces) make up about 1% of total body weight.2 See How body water is distributed. To maintain homeostasis, fluids need to be stable in the intravascular, interstitial, and IC spaces. The amount of IC fluid is rather stable in the body; intravascular fluid is the least stable and fluctuates in response to fluid intake and loss. Interstitial fluid is the reserve fluid, replacing fluid in the intravascular and IC spaces as needed.1,3 Almost all pathologies affect the fluid balance within the body, especially in critically ill patients. Fluid movement within the various body spaces depends on osmosis—movement of water through a selectively permeable or semipermeable membrane from a solution that has a lower solute concentration to one with a higher solute concentration—and diffusion, or the free movement of molecules or other particles in solution across a permeable membrane from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration, resulting in an even distribution of the particles in fluid. Fluid balance also is regulated by certain hormones: • Aldosterone, the principal mineralcorticoid produced by the adrenal cortex, promotes sodium retention by the distal tubules, while increasing urinary losses of potassium. This helps to prevent water and sodium losses through the kidneys. • Antidiuretic hormone (ADH), also known as vasopressin, is synthesized in the hypothalamus and stored in and released by the posterior pituitary gland. ADH triggers the renal tubules to reabsorb water and return it to the intravascular space. • Natriuretic peptides, such as atrial natriuretic peptide, released from the heart in response to cardiac chamber stretch and overfilling, increase sodium and water excretion by the renal distal and collecting tubules.2 Because the kidneys are the major organs involved in electrolyte and fluid homeostasis, determine the patient’s renal function before attempting to correct a patient’s electrolyte or fluid imbalance.4 Also, don’t let lab numbers or the numerous equations used for fluid replacement override sound clinical judgment. If the patient’s clinical condition 0 March l Nursing2011Critical Care l Copyright © 2011 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 31 Hyponatremia only be used in severe cases of In hyponatremia, water moves symptomatic hyponatremia from an area of low intravascular because it can rapidly induce sodium concentration to an area fluid volume overload.)7 We’ll of high sodium concentration. discuss the use of crystalloid The result is excess fluid volume solutions later. in the IC compartment and a fluid volume deficit in the EC Hypernatremia compartment. In hypernatremia, sodium pulls Signs and symptoms of hypowater from the IC space into the natremia vary depending on the intravascular space. The dehyspeed of onset, magnitude of drated cells shrink or shrivel, and sodium deficit, and cause. When the EC space becomes fluid overRemember that where serum sodium is less than 135 loaded. Signs and symptoms of sodium goes, water is mEq/L (hyponatremia), signs and hypernatremia include thirst (a sure to follow. symptoms generally reflect compensatory mechanism that’s hypoosmolality and movement troublesome in critically ill of water into muscle, neural, and gastrointestinal patients, who often are fluid-restricted or physically (GI) tissue resulting in muscle cramps, muscle unable to drink); signs and symptoms related to weakness, decreased deep tendon reflexes, headhyperosmolality and movement of water out of ache, mental status changes, dizziness, anorexia, neural tissue, including irritability, restlessness, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarheadache, disorientation, and decreased deep tenrhea.2 Serum and urine osmolality will be don reflexes; signs and symptoms related to decreased. In severe hyponatremia (serum sodium decreased IC fluid including dry skin and mucous of 115 mEq/L or less), you may notice muscle membranes, decreased skin turgor, and decreased twitching, focal weakness, papilledema, and signs salivation and lacrimation.2 The patient’s urine speof increasing intracranial pressure, such as letharcific gravity and osmolality increase, and central gy, confusion, hemiparesis, and seizures. Without venous pressure decreases. In severe hypernatretreatment, increased intracranial pressure can be mia (serum sodium of more than 160 mEq/L), the fatal.5 patient may develop seizure activity and coma.4 Hyponatremia is often caused by or associated Hypernatremia in critically ill patients can be with treatments and diagnoses common to patients caused by vomiting, diarrhea, open wounds, in CCUs. For instance, administering hypotonic I.V. hyperventilation, fever, hypertonic enteral tube solutions and some medications (such as thiazide feedings without water supplementation, nasogasdiuretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tric suctioning, GI drains, excessive administration and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) may of sodium-containing fluids such as 3% sodium contribute to the development of hyponatremia. chloride solution and sodium bicarbonate, and Hyponatremia also is associated with heart, liver, medical conditions such as diabetes insipidus and and kidney failure, which are common among criti- Cushing syndrome.5,7-9 cally ill patients.7 As with treating hyponatremia, you’ll implement When managing a patient with hyponatremia, measures to restore fluid balance in addition to corthe goal is to identify and treat the underlying cause recting the underlying cause of the sodium imbalof the sodium imbalance. Treatment will also ance. Treatment measures will depend on whether depend on whether the patient has a fluid balance the patient is hypovolemic, isovolemic (also called abnormality. euvolemic), or hypervolemic. Most critically ill Depending on the underlying cause, you may patients with hypernatremia are also hypovolemic, administer diuretics, restrict water intake, or so you’d administer isotonic or hypotonic sodium administer hypertonic saline (for example, 3% sodichloride solution as prescribed.10 Crystalloid soluum chloride solution, although this fluid should tions are discussed later. www.nursing2011criticalcare.com March l Nursing2011Critical Care l Copyright © 2011 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 33 Keeping electrolytes and fluids in balance, part 1 Fluid balance: Most critically ill patients will Dry or wet? need I.V. fluid replacement. Fluid imbalances are common Generally, replace fluid based on in critically ill patients. Fluid the type of fluid lost: blood transand electrolyte balance are fusions for blood loss, isotonic closely related in the sense that solutions for patients experiencelectrolyte imbalances can be ing diarrhea.11 avoided when you pay close Other I.V. fluids that are availattention to the patient’s nutriable for the treatment of hypovoletional status and the use of I.V. mia are colloids, which are highfluids.10 Causes of fluid volume molecular-weight substances that deficit in the critically ill patient under normal conditions don’t A critically ill patient can include GI loss, infection, pass through the semipermeable can be dehydrated renal loss, and third-space fluid membrane in the vascular space. while appearing fluid shifts. In contrast, causes of Colloid solutions are hypertonic, fluid volume excess are overadincreasing capillary oncotic presoverloaded. ministration of fluids, heart failsure and pulling fluid from the ure, renal failure, and certain medications. interstitial space into the vascular compartment. Medications may be indicated to treat the causes Dry: Dehydration of dehydration, such as antidiarrheals, antiemetics, Dehydration, or fluid volume deficit, is characterand antipyretics.12 ized by a decrease in EC fluid and occurs when fluid Third-spacing is another way a critically ill intake is less than the body’s fluid needs, when patient can be dehydrated while appearing fluid patients experience excessive loss of body fluids, or overloaded. Fluid that accumulates in these spaces when third-spacing sequesters EC fluid where it is physiologically useless because it’s not available can’t contribute to cardiac output. Isotonic fluid def- for use as reserve fluid or function. Causes of thirdicit is the most common type of fluid volume deficit, spacing include: in which there are proportionate losses in sodium • Injury or inflammation such as burns, sepsis, crush and other electrolytes and water. It’s almost always injuries, massive trauma, cancer, intestinal obstruccaused by a loss of body fluids and is often accomtion, and abdominal surgery. These all increase cappanied by a decrease in fluid intake.2 Without comillary permeability and let fluid, electrolytes, and pensatory mechanisms, perfusion to vital organs proteins leak from the intravascular space. may be decreased, so fluid replacement is vital. • High vascular hydrostatic pressure from renal failure Clinical manifestations of fluid volume deficit can or heart failure, which pushes abnormal volumes of develop rapidly. If you suspect that your patient is fluid from blood vessels. at risk for developing hypovolemia, assess for acute • Malnutrition and liver failure from cirrhosis, chronweight loss, increased thirst, decreased skin turgor, ic alcohol abuse, or starvation. These conditions dry mucous membranes, oliguria, high urine specifprevent the liver from producing albumin, thus ic gravity, weak and rapid pulse, flattened neck lowering capillary oncotic pressure.3 veins, increased temperature, decreased central Treating third-spacing can be challenging. venous pressure, muscle weakness, postural hypoOsmotic diuretics can be used to mobilize some of tension, and cool, clammy pale skin related to the fluid back into the intravascular space for elimiperipheral vasoconstriction.2,5 Being familiar with nation by the renal system. However, this is usually these clinical findings lets you quickly identify and only a temporary measure because of the nature of intervene for patients and avoid potential medical the disease processes that caused the third-spacing. emergencies. Large third space fluid collections can be physically Treatment of fluid volume deficit includes removed (by paracentesis for ascites or thoracenteprompt identification and treatment of the underlysis for pleural effusion), and then the vascular space ing cause and fluid replacement. can be rehydrated with I.V. fluids.3 34 l Nursing2011Critical Care l Volume 6, Number 2 www.nursing2011criticalcare.com Copyright © 2011 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Wet: Overhydration in this series will focus on manFluid overload or fluid volume aging the remaining electrolytes excess is a clinical sign of fluid that are part of the “critical care retention or intake that exceeds shuffle.” ❖ the body’s fluid needs. Hypervolemia refers to increased fluid in the intravascular and REFERENCES 1. Huether SE, McCance KL. Understanding interstitial spaces. A critically ill Pathology. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby patient with a severe fluid overElsevier; 2008:99-120. load or poor cardiac function is at 2. Porth CM. Essentials of Pathophysiology: Concepts of Altered Health States. 3rd ed. risk for acute pulmonary Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and 12 edema. Wilkins; 2011. Overhydrated Signs and symptoms of fluid 3. Hogan MA, Gingrich MM, Overby P, patients are at risk Ricci MJ. Fluids, Electrolytes, & Acid-Base volume excess include acute Balance. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: for dependent edema weight gain, full and bounding Prentice Hall; 2007:1-80. 4. Buckley MS, Leblanc JM, Cawley MJ. pulses, distended neck veins, puland skin breakdown. Electrolyte disturbances associated with monary crackles, peripheral commonly prescribed medications in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(suppl 6):S253-S264. edema, and elevated central venous pressure. 5. Mulvey M. Fluid and electrolytes: balance and disturbance. In: Volume-overloaded patients can develop flash (or Surrena H, ed. Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing. 12th ed. Philaacute) pulmonary edema, a life-threatening complidelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010:270-277. cation that requires swift intervention to prevent 6. Johnson KL. Determinants and assessment of fluid and electrolyte balance. In: Connor M, ed. High-Acuity Nursing. 5th ed. Upper respiratory arrest. Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2010:606-620. Pharmacotherapy for the overhydrated critically 7. Adams K. Patient management: renal system. In: Morton PG, ill patient consists of diuretics such as furosemide, ed. Critical Care Nursing: A Holistic Approach. 8th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008:680-684. bumetanide, or torsemide. These diuretics can also 8. Hayes DD. How to respond to abnormal serum sodium levels. cause electrolyte losses, so frequently monitor the Nursing. 2007;37(12):56hnl-56hn4. patient’s serum electrolyte levels and ECG. 9. Corwin EJ. Handbook of Pathophysiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008:12-14. Because of dependent edema, patients are at risk for developing skin breakdown, such as in the sacral 10. Sedlacek M, Schoolwerth AC, Remillard BD. Electrolyte disturbances in the intensive care unit. Semin Dial. 2006;19(6):496-501. area. Turn and reposition the patient at least every 11. Oh H, Seo W. Alterations in fluid, electrolytes and other serum 2 hours to decrease the risk of skin breakdown. chemistry values and their relations with enteral tube feeding in Nutritional interventions include limiting sodium acute brain infarction patients. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(2):298-307. 12. Ignatavicius DD, Workman ML. Medical-Surgical Nursing: and fluid intake. For example, at discharge, the Patient-Centered Collaborative care. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2010:170-198. patient and family may need to be taught how to read food labels in order to limit dietary sodium RESOURCES intake. The patient also may need long-term fluid Gregori JA, Nunez JM. Handling of water and electrolytes in the management. healthy old. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2009;19:1-12. To determine whether therapy has been effecHarvey S, Jordan S. Diuretic therapy: Implications for nursing practive, monitor the patient’s intake and output and tice. Nurs Stand. 2010;24(43):40-49. daily weight. Patients should be weighed at the Morton PG, Fontaine DK. Critical Care Nursing: A Holistic Apsame time every day; a rapid weight gain is the car- proach. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:727-757. dinal sign of fluid retention and overload. Nelson DP, Lemaster TH, Plost GN, Zahner ML. Recognizing sepsis in the adult patient. Am J Nurs. 2009;109(3):40-45. Staying in balance As you’ve learned, the levels of sodium and body water can shift up or down. Assessing the volume status of the critically ill patient is notoriously more challenging to detect than electrolyte abnormalities, which can be measured directly.10 The next article www.nursing2011criticalcare.com Scales K, Pilsworth J. The importance of fluid balance in clinical practice. Nurs Stand. 2008;22(47):50-57. At Duquesne University School of Nursing in Pittsburgh, Pa., Alicia L. Culleiton is an assistant clinical professor and Lynn C. Simko is an associate clinical professor. DOI-10.1097/01.CCN.0000394395.67904.4d March l Nursing2011Critical Care l Copyright © 2011 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 35