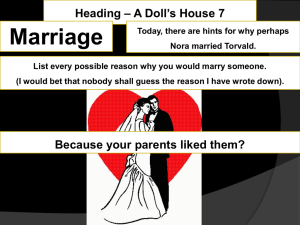

Sam Gaines 12ECB A Doll’s House 4 PQE’s In the opening scene of the play, Nora gives the impression of being very family-oriented and contented, but also a little naïve. The first line immediately shows the audience Nora’s primary concern – “Hide the Christmas tree carefully, Helen. Be sure the children do not see it until this evening, when it is dressed.” She clearly cares deeply about her children’s Christmas experience. This clear family-centredness is displayed throughout the opening scene, including her long list of presents for the children and for the “full three weeks beforehand” she spent making Christmas ornaments. A stereotypical characteristic of a married Victorian woman, the clear display of maternality shown by Nora shows her to be conforming to the traditional gender roles of the 1870’s. Furthermore, in keeping with the theme of conforming to traditional gender roles, Nora also appears at first to be quite naïve when discussing debt with Torvald, “I don’t suppose I should care whether I owed money or not”. This is another stereotypical trait of many Victorian women, but can also be viewed with a certain sense of irony when reading the play for a second time, when Nora’s exploits into the financial world are revealed. Her satisfaction with the both her role in the household and more generally with her petit-bourgeois lifestyle (communicated by the setting “furnished comfortably and tastefully, but not extravagantly”) is exhibited throughout the opening scene, most notably by the stage directions, “smiling”, “smiling quietly and happily”. All these aspects of our first impressions of Nora show her as traditional, conforming and satisfied – but Ibsen injects a small note of rebelliousness into Nora’s personality with her buying macaroons in secret, “She takes a packet of macaroons from her pocket and eats one or two” and subsequently lying to her husband about it, “No, Torvald, I assure you really—“. This foreshadows future non-conformity and hints, perhaps, that there are other things that she is also keeping from her husband. The audience’s impression of Torvald in the opening scene is similarly conformist and traditional for the 1870’s. He is portrayed as responsible, masculine and slightly patronising. His financial responsibility is exemplified in his opinions about debt, “There can be no freedom or beauty about a home life that depends on borrowing and debt.” This also comes across as fairly moralistic, even judgemental, and is a crucial aspect for the plot later in the play. Like Nora’s stereotypical femininity, his thriftiness was a traditional masculine trait during the Victorian times, when debt was heavily looked down upon. He also clearly feels responsibility for Nora, with constant affectionate sobriquets, “my little lark” and “my little squirrel”, which after a while start to appear slightly patronising. Nora’s infantilization by Torvald is very noticeable and modern audiences likely feel somewhat uncomfortable with the constant (possibly even demeaning?) remarks. This also establishes Torvald as reasonably possessive, treating Nora more like a pet or status symbol than an independent human being. In fact, Torvald is certainly much more independent than Nora, with his own office and power of the house’s finances. His ecstasy at finally having a “perfectly safe appointment, and a big enough income”, while perfectly understandable, perhaps serves also to emphasise once again the importance that status symbols, such as a high income or pretty wife, have for him. Lastly, Torvald also maintains a sense of formality throughout, with the script referring to him as “Helmer”, a courtesy not extended to Nora. This echoes the stereotypical theme of the outside being the realm of the masculine, with the household being the realm of the feminine, cementing the dominance of orthodox gender roles in this relationship. Nora and Torvald’s marriage is a very typical Victorian affair – Nora is feminine, innocent and contented while Torvald is masculine and protective. Their relationship appears at first glance to be a very loving one, with Torvald’s affectionate sobriquets, “my little lark” and Nora’s happiness, “smiling quietly and happily” showing that they both have great love for each other. However, while Torvald shows Nora great affection, he seems to have little respect for her, given the almost demeaning nature of some of his playful nicknames such as “featherbrain”. Many modern women would view such comments as patronising, but Nora currently appears content with her treatment. Furthermore, the marriage largely appears not to be built on honesty, a foundation most would consider critical in a relationship. Nora’s lies about her escapades in town, “Not even takes a bite at a macaroon or two? / No, Torvald, I assure you really—“, while not especially serious, reveal that Nora certainly is not in the habit of telling her husband the whole truth and, as mentioned above, foreshadow future deception. With that said, Nora is still largely portrayed as obedient, “As you please, Torvald” at this point in the play. The word choice is fitting – it is as he pleases, implying that he holds the power, both pecuniary and otherwise, in the relationship. Ibsen gives the audience many clues about Nora and Torvald’s way of life, mainly from stage direction. They are of moderate wealth and are most likely of bourgeoise or petit bourgeoise milieu. Their house is “furnished comfortably and tastefully, but not extravagantly”, showing that the couple is by no means poor, but at the same time not exceedingly wealthy. They own “a piano”, implying they are reasonably well cultured and reinforces the “tasteful” atmosphere. The setting is very realistic for the time, as Ibsen was a pioneer of naturalism, a literary style known for extreme realism, and showing how environment, heredity and social conditions shape human beings. In fact, the sole setting for the entire play is Torvald’s living room, presumably a deliberately mundane choice in order to allow the audience to identify more with the two main characters and superimpose their own lives onto those of Nora and Torvald. Nora “carries a number of parcels”, including “a new suit for Ivar, and a sword”, which all further cement the family as being well-off, but not overly so, and can afford and maid and a porter. Torvald has “a perfectly safe appointment” at a bank, and a “big enough income” displaying their relative economic security – indeed, they don’t seem to have any serious problems in their life at the moment, the largest source of discontent currently appearing to be over Nora’s Christmas present. In sum, the Helmer’s way of life is very comfortable at present – they are middle class, economically secure and reasonably socially well-off.