Bhaskar's From East to West: New Left, New Age Synthesis

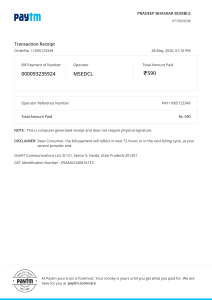

advertisement