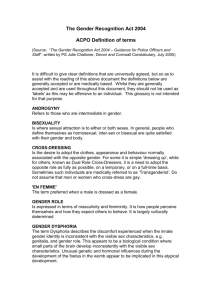

Kirk Greenwood Prof. Andrews PSYC280-N02 15 November 2018 Historical antecedents: • • • • • Anthropological/Prehistoric History, anthropology, biology show non-binary gender identities, gender transformations and transpositions, in the animal kingdom and human societies throughout history and across cultures (Lev, 2013, p. 291). Religious Most world religions codify socially acceptable expressions of gender and sexuality. Western societies, particularly America, are influenced by JudeoChristian religious beliefs about the proper roles of men and women. Ancient religious texts stipulate punishments, up to and including death, for gender-role transgression. Passages in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament explicitly forbid cross-dressing (Deuteronomy 22:5) and physical alterations of male/female sex organs (Leviticus 22:24 ) (Drescher, 2010, p. 440). Historical antecedents: Scientific Naturalism • As Western Europe modernized and secularized in the 19th century, scientific and medical explanatory models supplanted religious and supernatural explanations of natural phenomena (Drescher, 2010, p. 440). • Such ‘sins’ were reclassified as ‘illnesses’: demonic possession redefined as insanity, drunkenness as alcoholism, and sodomy as an illness called homosexuality (Drescher, 2010, p. 440). Sexual Deviance • “In the mid-1880s, there was an explosion of anthropological, sociological, psycho-medical, and judicial explorations into abnormal sexual behavior, with a specific focus on libidinous desire, particularly in women and children, and sexual deviations, like inversion (cross-gendered homosexuality) and hermaphroditism (intersexuality)” (Lev, 2005, p. 38). Early Clinical Accounts: Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1825-1895) Ulrichs (1870) theorized that some men, whom he called urnings, were born with a ‘woman’s spirit;’ likewise, some women, called urningins, had a man’s spirit trapped inside a woman’s body. (Drescher, 2014, p. 430) Ulrichs’ 1870 tract, Uranus In his seminal Psychopathia Sexualis (1886), KrafftEbing documented cases of gender dysphoric and gender variant individuals born to one sex, yet living as another. (Drescher, 2010, p. 436) Krafft-Ebing’s 1886 tract, (1840Psychopathia Sexualis Hirschfeld was the firstRichard von Krafft-Ebing 1902) clinician to distinguish homosexuality from transgenderism. His patient, Lili Elbe, born male, was the first documented person to successfully complete sex reassignment surgery. Lili Elbe, born Einar Mogens Wegener, (Drescher, 2010, p.436) Magnus Hirschfeld (1868-1935), seated at right, with friends at a party at his Institute for Sexual Research in Berlin. before and after her transition in 1930. Early Reactions to Transsexualism in U.S.: 1950-1970 • In 1952, George Jorgensen has sex reassignment surgery (SRS) in Denmark, returning to U.S. as Christine Jorgensen. • Doctors who performed Jorgensen’s SRS publish a report in Journal of the American Medical Association. • Increase in popular and scientific awareness in U.S. of individuals wishing to ‘cross over’ (Drescher, 2010, p. 436) Sensationalist New York Daily News headline about George Jorgensen’s transition to Christine. U.S. psychiatry tended to view transsexuals as “confused homosexuals, neurotics, transvestites, [or] schizophrenic” in need of psychotherapy and ‘reality testing’ (Drescher, 2010, p. 438) Psychoanalytic ego psychology, the reigning paradigm in U.S. psychiatry at mid-century, viewed gender fluidity, or uncertainty, as pathological. (Drescher, 2010, p. 434) Green (1969) surveyed 400 psychiatrists and other medical specialists regarding their opinions of a transsexual requesting SRS. Patient characteristics: Requested procedures: “30-year-old biological male” “very effeminate in his mannerisms, interests, and daydreams” “removal of both testes, his penis” “breasts be made to appear like a woman’s” wants to “dress exclusively in women’s clothes” “breasts be made to appear like a woman’s” sexual desire for men feels and expresses “he is a female trapped in a male body” *Respondents informed that procedures are “medically possible” (Green, 1969, p. 236) Results: • 15% of responding clinicians considered the patient “psychotic” • 8% considered him “severely neurotic • Most opposed his request • • • • Medical Model of Transsexualism: 1960-1980 Disputed psychoanalytic view that gender dysphoric people were psychotic/neurotic Founded gender clinics where gender dysphoric people could receive medical care and SRS Expanded professional awareness and knowledge about gender identity and SRS Changed psychiatric and public opinion regarding the authenticity of transsexualism (Drescher, 2010, p. 442) Leading Figures: Harry Benjamin (1885-1986), endocrinologist • Gender dysphoria exists a continuum, from transsexual to transvestite (Lev, 2005) • Male-to-female (MF) transsexualism was a biological disorder caused by brain being ‘feminized’ in utero (Drescher, 2010) • Pioneered treatment of gender dysphoric people using sex hormones (Drescher, 2010) • Treated and befriended ~1000 transsexuals in U.S. (Drescher, 2010) • Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association, a professional organization dedicated to health of gender dysphoric people (now called WPATH), named in his honor upon its founding in 1979 (Drescher, 2010) John Money (1921-2006), psychologist • Studied gender assignment in children with disorders of sex developmentEarly psychosocial environment, particularly the family, plays key role in gender formation • Individual gender identity fixed by 3 years old; difficult or impossible to change with psychotherapy • Coined the term “gender role” – “things a person says or does to disclose himself or herself as having the status of boy or man, girl or woman” • Viewed gender identity as the private experience of gender role and gender role as the public manifestation of gender identity • Headed the Johns Hopkins Gender Identity Clinic in 1965, the first of 40 academic gender clinics to perform SRS in the U.S. (Drescher, 2010, p. 437-438) • 6 revisions of DSM since it was first published • DSM-I or DSM-II do not mention gender Gender Identity and the DSM: 1980-2000 DSM-I (APA, 1952) DSM-II (APA, 1968) DSM-III (APA, 1980): • Transsexualism & Gender Identity Disorder of Childhood (GIDC) added DSM-III-R (APA, 1987): • Gender Identity Disorder of Adolescence and Adulthood, non-transsexual type added DSM-IV (APA, 1994): • Gender Identity Disorder of Adolescence and Adulthood, non-transsexual type (removed) • Transsexualism and GIDC conflated into Gender Identity Disorder (GID), a single diagnosis with different criteria sets for children and adolescents/adults (Lev, 2013, p. 291) Despite these permutations, the core criteria for transsexualism or GID remain consistent after 1980: (Cohen-Kettenis & Pfäfflin , 2010, p. 505) In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.) (APA, 2013) In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.) (APA, 2013) Biogenetic Risk Factors: Genetic Heritability: • Gender dysphoria is more common in people who have sibling with the disorder • A study of 23 pairs of identical twins found that when one of the twins displayed gender dysphoria, the other twin displayed it as well in 9 of the pairs Brain Structure and Function: • People with gender dysphoria tend to have different blood flow patterns in brain areas related to sexuality and consciousness – – increased blood flow to insula and reduced decreased blood flow in the anterior cingulate cortex Area of the hypothalamus called the bed nucleus of stria terminalis (BST) was smaller in a sample of six MF transsexuals than in cisgendered men – – Cisgendered women usually have smaller BST than men BST thought to affect sexual behavior in male rats 357) (Comer, 2014, p. Prenatal Development: Hare et al. (2009) found variation in genes coding for androgen receptors may be related to the development of gender dysphoria in fetuses with XY sex chromosomes (i.e., biological males) (Davy, 2015, p. 1170) Fluctuations in production or absorption of androgen in fetuses with may predispose them to developing gender dysphoric symptoms (Zucker & Lawrence, 2009, p. 12) Psychosocial Risk Factors: Herschkowitz (2000) warns against overrelying on the biogenetic explanations citing “constant close interaction of genome, environment, and behavior” in postnatal child development: Genes code for proteins, and not directly for behavior. The proteins are a basis for metabolism, structure formation and physiological functions. Gene realization, however is modulated by environmental factors. (p. 451) TGNC persons encounter pervasive discrimination and systemic oppression in the United States… and, as a result, are susceptible to higher rates of mental health disparities. (McCullough, Dispenza, Parker, Viehl, Chang, & Murphy, 2017, p. 423) According to a study of 6,450 TGNC participants in the United States, over 86% reported experiencing sexual and physical assault, career-related discrimination, school bullying and harassment, homelessness, relationship losses, and denial of medical services (McCullough et al., 2017, p. 423) [M]ental health concerns can be by-products of discrimination and prejudice experienced by TGNC persons. The stigma against TGNC persons may increase the likelihood that they will utilize mental health services at a rate similar to sexual minority populations. (McCullough et al., 2017, p. 423) Assessing Gender Dysphoria in Children 1). Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1981): a widely used parent-report behavior problem questionnaire, which includes two items (out of 118) that pertain to cross-gender identification: “behaves like opposite sex” and “wishes to be of opposite sex.” (Zucker & Lawrence, 2009, p. 10) 2). Gender Identity Questionnaire for Children (Johnson et al., 2004): a parent-report measure of gender identity and gender role behavior with 16 items covering a range of sex-typed behaviors corresponding to DSM criteria for Gender Identity Disorder in children • Questions: peer affiliation, roles in fantasy play, sexof-playmate preference, toy interests, cross dressing; gender identification; anatomic dysphoria • Items rated on a 5-point scale for frequency; lower scores reflect more cross-gendered behavior • Short, targeted, quantitative, and standardized • Useful screening tool for front-line clinicians (Johnson et al., 2004) Assessing GD in Adolescents/Adults 1). Biographical Questionnaire for Transsexuals and Transvestites (Doorn et al., 1994): • structured interview used in all Dutch gender clinics • 211 items about sociodemographic information, childhood and preadolescent gender behavior, gender development in adolescence/adulthood, transvestite practice, sexual orientation 2). Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale (Cohen-Ketternis & van Goozen, 1997; Doorn et al., 1996): • 12 questions given on a 5-point scale, from “agree completely” to “disagree completely” • Higher score indicates more gender dysphoria (range 12-60) • Designed for first Dutch follow-up of SRS to evaluate outcomes • Modified for use in other Dutch and international follow-up studies • Separate versions for natal males and natal females Other Gender Identity/Gender Dysphoria Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults (Deogracias et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2010) • 27-item dimensional assessment of gender identity/dysphoria • Conceptualizes gender identity as a bipolar continuum with a male pole and a female pole and varying degrees of gender gender uncertainty, or gender identity dysphoria, transitions between the poles Prevalence of Gender Dysphoria in Children • Zucker and Lawrence (2009) state that estimates of prevalence in children rely on indirect methods of data collection, such as: – parental endorsement of behavioral items pertaining to gender dysphoria on omnibus questionnaires for children – referral rates to clinics specializing in the treatment of childhood gender dysphoria • • Surveys of U.S. mothers indicate that about 1.5 percent of young boys wish to be a girl, and 3.5 percent of young girls wish to be a boy. (Comer, 2014, p. 357) Internationally, Cohen-Kettenis, Owen, Kaijser, Bradley, & Zucker (2003) compared historical on children referred to two clinics for gender dysphoric behavior: Gender Identity Clinic Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Toronto, Canada (1974-2000) • Sex ratio of 5.75:1 of boys to girls in 358 children (ages 3-12) Gender Clinic Department of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, University Medical Center Utrect, Netherlands (1988-2000) • Sex ratio of 5.75:1 of boys to girls in 358 children (ages 3-12) • At both clinics, girls showed higher average levels of cross-gender behavior than boys. • Despite this, girls were referred for treatment an average of 10 months later than boys. (Cohen-Kettenis et al., 2003) Prevalence of Gender Dysphoria in Adolescents/Adults • • As with children, the best indirect method to measure population prevalence of gender dysphoric adults is data on patients at hospital- and university-based gender clinics, which serve as gateways for SRS. (Zucker & Lawrence, 2003, p. 13) DSM 5 (APA, 2013): Population prevalence of gender dysphoria among U.S. adults is: 0.005-0.014% of natal males and 0.002-0.003% of natal females • Figures “likely modes underestimates” because not all adults seek the full complement of SRS services at gender clinics (APA, 2013, p. 454) Coleman et al. (2012) suggested clinics are not “affordable, useful, or acceptable” to meet the needs of all gender dysphoric individuals. (p. 7) • Thus, indirect estimates fail to account for: – People seeking care elsewhere (e.g., individual/family therapy, peer support, facial surgery) – Those not seeking treatment (p. 7) Zucker and Lawrence (2009) analyzed records from 25 gender clinics worldwide and developed “crude estimates” of trends in adult prevalence: • • More MFs attend clinics than FMs by a ratio of roughly 2:1 FMs apply for and undergo SRS at younger ages than MFs (p. 13) 1960s-1990s: 300-800% increase in gender dysphoric patients presenting at Western European clinics (p. 16) Comorbidities: GD Children & Teens Children: • • • Co-occurring disorders in clinically referred children with gender dysphoria include “internalizing disorders,” such as anxiety and depression and “externalizing disorders,” such as disruptive and impulse-control disorders Gender dysphoric children also have higher rates of autism spectrum disorders than the general population. (APA, 2013, pp. 458-459; Coleman at al., 2010, p. 12) Children and adolescents who do not conform to socially prescribed gender norms may experience harassment in school… putting them at risk for social isolation, depression, etc. (Coleman et al., 2010, p. 14) Adolescents: • • • Co-occurring disorders in clinically referred adolescents with gender dysphoria include anxiety, depression, autism spectrum disorders, and the externalizing disorder, oppositional-defiant disorder. (APA, 2013, p. 459; Coleman et al., 2010, p. 13) Comorbid symptoms are sometimes more prevalent and intense in adolescents when compared to children. (Coleman et al., 2010, p. 13) Prior to reassignment procedures, adolescents (and adults) with gender dysphoria are at increased risk for suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicides. – Suicide risk may persist after procedure(s). (APA, 2013, p. 454) Comorbidities: Gender Dysphoric Adults All age groups: Gender dysphoria… is associated with high levels of stigmatization, discrimination, and victimization, leading to negative self-concept, increased rates of mental disorder comorbidity, school dropout, and economic marginalization, including unemployment, with attendant social and mental health risks, especially in individuals from resource-poor backgrounds. (APA, 2013, p. 458) Cole, O’Boyle, Emory, and Meyer (1997) evaluated 435 self-reported transsexuals applying for SRS at a gender clinic for histories of substance abuse, psychiatric disorders, self-harm, and suicidality. • • • • Sample: 318 MFs & 117 FMs, respective average ages 32 & 30 A authentic sample would show “commitment and involvement in the ‘real life’ transition process” (p. ) >60% undergoing hormone therapy ~30% MtF & 50% FtM previously underwent facial surgery and/or chest augmentation/reduction (Cole et al., 1997, p. 15-17) Research Methods: • 1-2 hour clinical interview • Intake questionnaire collecting biographical/sociodemograph ic, medical-psychosocial information • 93 MFs and 44 FMs also completed MMPI (Cole et al., 1997, p. 15)general population. Findings: Incidence of diagnosable psychiatric issues similar to A majority of individuals had long-term employment, lasting friendships and relationships, and fulfilling lifestyles. (Cole et al., 1997, p. 21) Cole et al. (1997), Cont. Substance Abuse • 29% MF & 26% FM reported past substance abuse that: • • Negatively affected a job/relationship OR Required treatment through counseling or a recovery program • All above participants stated substance use was a way of coping with gender dysphoria (Cole et al., 1997, p. 17-18) Suicidality • 12% MF & 21% FM had attempted suicide at least once • • • • • • Subjective descriptions: “feeling isolated” “not able to talk to others” familial or social rejection “disgust with anatomic state” hopelessness (Cole et al., 1997, p. 19) Mental Health: • 9% of participants had been treated for mood, psychotic, personality, and/or nuerodevelopmental disorders • Depression was the most common treated disorder • ~60% of patients with mood or psychotic disorders were receiving ongoing drug therapy (Cole et al., 1997, p. ) Prognosis: Gender Dysphoric Children & Adolescents Children: • Gender dysphoria in childhood does not inevitably continue into adulthood. • Cohen-Kettenis (2001) and Zucker and Bradley (1995) conducted follow-up studies of children (mainly boys) referred to clinics for gender dysphoria: – 6-23% of these children experienced a persistence of symptoms into adulthood – Boys in these studies were more likely to identify as gay in adulthood than transgender • 12-27% persistence rate in newer studies with more female participants (Coleman et al., 2010, p. 11) Adolescents: • The persistence of gender dysphoria into adulthood appears to be much higher for adolescents. • In a follow-up study of 70 adolescents who were diagnosed with gender dysphoria and given puberty suppressing hormones, all continued with actual sex reassignment • (Coleman et al., 2010, p. 11) Prognosis: Gender Dysphoric Adults • Studies as early as 1990 saw adult patient satisfaction with SRS to be as high as 87% in MFs and 97% in FMs • Steady increase in patient satisfaction with SRS outcomes over the years • Quality of surgical results is a strong predictor of future satisfaction • Meta-analyses of follow-up studies of SRS patients show improved sense of wellbeing, ratings of physical attractiveness, sexual function… even income levels Cole et al. (1997) comorbidity study (Coleman et al., 2012, pp. 7-8) produced subjective reports of increased happiness, competency, and productivity in work and leisure pursuits. Participants credited SRS with decreasing in self-destructive behaviors, including substance abuse, self-harm, suicide attempts (p. 24) Johansson et al. (2010) reviews Swedish literature on risk factors for negative outcomes of SRS, which cites poor or lacking familial and social support, severe psychopathology, unfavorable physical appearance, and poor surgical result. (p. 1430) (De Cuypere et al., 2005) Note: Data typically reflects outcomes for adults receiving both hormone therapy and SRS. Current methods make it difficult to determine efficacy of hormone therapy alone in relieving gender dysphoria. Dutch study of SRS outcomes in adolescents & adults • Smith, Van Goozen, Kuiper, & Cohen-Kettenis (2005) studied outcomes for adult and adolescent patients seeking SRS at the VU University Medical Centre in Amsterdam or University Medical Centre, Utrecht. • Patients tracked by age, sex, sexual orientation, onset age of gender dysphoria, crossgender symptoms in childhood, and gender dysphoria at assessment. Gender dysphoria, body dissatisfaction, evaluation of treatment and surgical results, and psychological, social, sexual functioning were assessed between one and four years after surgery. • Of the 325 patients who applied for sex reassignment therapy, 222 started hormone treatment and 188 completed sex reassignment surgery (Smith et al., 2005, p. 91). • All patients who underwent both hormonal and surgical intervention showed improvements in their mean gender dysphoria scores on the Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale. • 91.6% were satisfied or very satisfied with their overall appearance after surgery. • 98.4% of patients expressed no regrets about sex reassignment after surgery (Smith et al., 2005, p. 94). *One MtF expressed deep regrets. She indicated that professional guidance regarding adverse consequences (i.e., intolerance of society, family and her own children), would have made the transition more endurable (p. 97) Dutch study, cont. Satisfaction with surgery: • Overall, MtFs showed greater satisfaction with surgical results than FtMs, perhaps due to the fact that FtMs are generally advised to postpone metaidoioplasty (transformation of the hypertropic clitoris into a micropenis) or phalloplasty in view of steadily improving surgical techniques. • 70% of MtFs were satisfied with their vaginoplasty. • 65.4% MtFs were satisfied with their breast augmentation. • 28.9% of FtMs were satisfied with breast removal; 57.9% were not completely satisfied (Smith et al., 2005, p. 95) *“Dissatisfaction with appearance predicted poor post-operative functioning, either because it directly and adversely affected psychological stability or mood, or it indirectly affected the way they were socially treated (or a combination of both)” (Smith et al., 2005, p. 98). Relationships and sexuality: • 88.5% of participants who had a sexual partner at follow-up were satisfied with their sex lives. • 82.4% of participants were sexually active at follow-up (Smith et al., 2005, p. 95). • MtFs and FtMs showed equal satisfaction with their sex lives (Smith et al., 2005, p. 97) Dutch study, cont. Psychological functioning: • The psychological functioning of patients was measured using two indexes: – Dutch Short MMPI – 83 items measuring negativism, somatization, shyness, psychopathology, and extroversion – Symptom Check List – 90 items inquiring into recent symptoms of agoraphobia, anxiety, depression, somatization, obsession/compulsion, suspicion, hostility, and sleep disturbance (Smith et al., 2005, p. 92) • MMPI scores in most categories of psychological functioning were within average ranges for the Dutch population as a whole both before and after treatment, the exceptions being high pre-test scores for somatization and low post-test scores for extroversion. • MMPI scores showed varying degrees of improvement in negativism, shyness, somatization, psychopathology, and extroversion in MtF and FtM patients. • MtFs rated as more depressed than FtMs on the Symptom Check List post-test (Smith, 2005, p. 94). *“A non-homosexual orientation, with more psychopathology and dissatisfaction with secondary sex characteristics predicted unfavourable post-operative functioning” (Smith et al., 2005, p. 98). Dutch study, cont. Social adjustment and acceptance: • 42% of patients had jobs or were students; 56.3% were unemployed. • 56.2% lived independently and 25.7% cohabitated with another adult without children (Smith et al., 2005, p. 94). • 98% felt they were completely taken seriously by most people. • 89% felt accepted by most people, 7.9% by some, 3% by no one. • 83.2% felt supported in their new gender role by everyone or almost everyone they knew. • 96.1% reported they could rely on at least some others during difficult times. • 20% felt they were sometimes being laughed at or had been ridiculed by strangers (Smith, 2005, p. 95) Five-year follow-up study of Swedish adults • • • • • • • • Johansson, Sundbom, Höjerback, and Bodlund (2010) investigated the clinicians’ and patients’ evaluations of the sex reassignment process at a Swedish gender clinic after five years and/or two years after surgery Patients (42 MtFs & 17 FtMs) responded to semi-structured interview questions about relief of gender dysphoria, use of mental health services, state of physical health, employment and finances, quality of intimate, family, and social relationships, and sexuality 95% of patients rated themselves as “globally improved,” with no difference between sexes 90% of patients satisfied with hormone therapy; 67% satisfied with genital surgery 38% of patients had a partner: 36% of MtFs & 41% of FtMs 62% of patients were employed or students 95% of patients reported their sex life as improved or unchanged after sex reassignment and hormone therapy Clinicians rated 62% of patients as “globally improved,” 24% as “unchanged,” and 14% as “worse” based on work situation, social relationships, financial situation, romantic partnerships, use of psychiatric care and Global Assessment of Functioning References Arcelus, J., Bouman, W. P., Van Den Noorgate, W., Claes, L., Witcomb, G., Fernandez-Aranda, F. (2015). European Psychiatry, 30, 807-815. Bockting, W. O., Knudson, G., & Goldberg, J. M. (2006). Counseling and mental health care for transgender adults and loved ones. International Journal of Transgenderism, 9(3/4), 35-82. Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & Pfäfflin, F. (2010). The DSM diagnostic criteria for gender identity disorder in adolescents and adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(2), 499-513. Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Wallien, M., Johnson, L. L., Owen-Anderson, A. F. H., Bradley, S. J., & Zucker, K. J., (2006). A parent- report gender identity questionnaire for children: A cross-national, cross-clinic comparative analysis. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 11(3), 397-405. Cole, C. M., O’Boyle, M., Emory, L.E., & Meyer III, W. J. (1997). Comorbidity of gender dysphoria and other major psychiatric diagnoses. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26(1), 13-26. Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., De Cuypere, G., Feldman, J., Fraser, L., Green, J., Knudson, G., Meyer, W. J., & Monstrey, S., (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people (7th version). Minneapolis, MN: The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. De Cuypere, G., T’Sjoen, G., Beerten, R., Selvaggi, G., De Sutter, P., Hoebeke, P. … Rubens, R. (2005). Sexual and physical health after sex reassignment surgery. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 34(6), 679-690. Deogracias, J. J., Johnson, L. L., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., Kessler, S. J., Schober, J. M., Zucker, K. J., (2007). The gender identity/gender dyphoria questionnaire for adolescents and adults. Journal of Sex Research, 44(4), 370-379. Devor, A. H. (2004). Witnessing and mirroring: A fourteen stage model. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy, 8(1/2), 41-67. Doorn, C. D., Poortinga, J., Verschoor, A. M., (1994). Cross-Gender Identity in Transvestites and Male Transsexuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 23(2), 185201. Johansson, A., Sundborn, E., Höjerback, T., & Bodlund, O. (2010). A five-year follow-up study of Swedish adults with gender identity disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(6), 1429-1437. Johnson, L. L., Bradley, S. J., Birkenfeld-Adams, A. S., Radzins Kuksis, M. A., Maing, D. M., Mitchell, J. N., Zucker, K. J, (2004). A parent-report gender identity questionnaire for children. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(2), 105-116. Knudson, G., De Cuypere, G., & Bockting, W. (2010b). Recommendations for revision of the DSM diagnoses of gender identity disorders: Consensus statement of The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. International Journal of Transgenderism, 12(2), 115-118. Smith, Y. L. S., Van Goozen, S. H. M., Kuiper, A. J., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., (2005). Sex reassignment: Outcomes and predictors of treatment for adolescent and adult trannsexuals. Psychological Medicine, 35(1), 88-99. Zucker, K. J., & Lawrence, A. A. (2009). Epidemiology of gender identity disorder: Recommendations for the standards of care of The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. International Journal of Transgenderism, 11(1), 8-18.