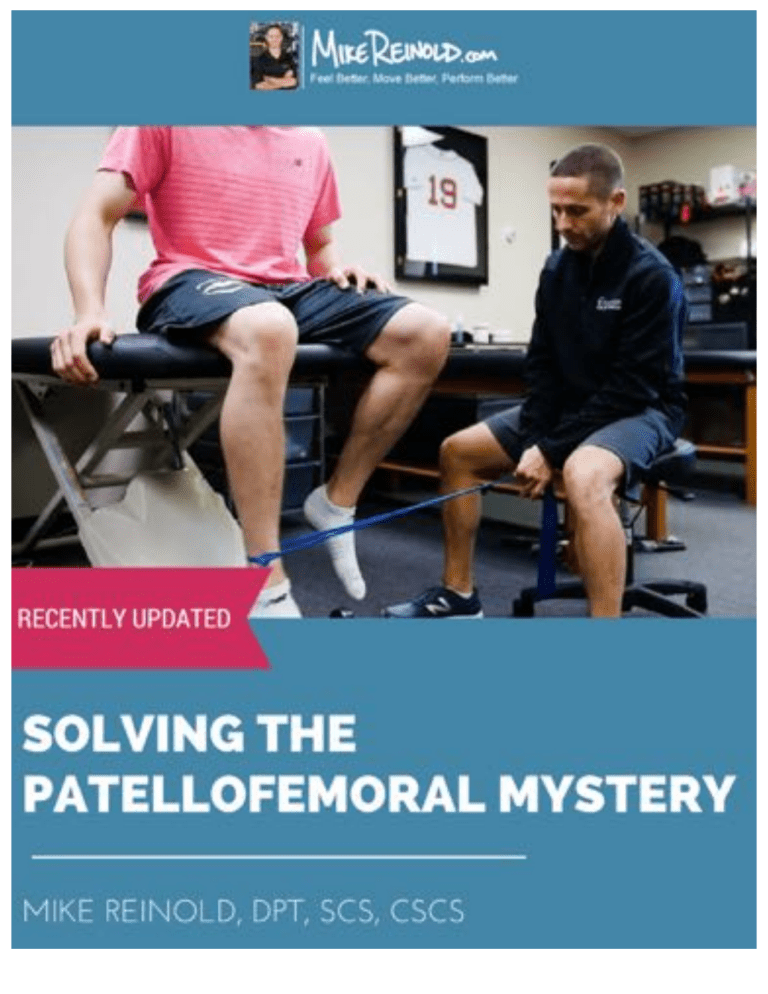

MikeReinold.com - Page 1 Solving the Patellofemoral Mystery Mike Reinold, PT, DPT, SCS, CSCS Chapter 1: Introduction – Solving the patellofemoral mystery Chapter 2: What causes patellofemoral pain? Chapter 3: Differential diagnosis of patellofemoral pain Chapter 4: Principles of patellofemoral joint rehabilitation Chapter 5: Specific treatment guidelines for patellofemoral pain Chapter 6: Biomechanics of the patellofemoral joint – clinical implications Chapter 7: Understanding the clinical implications of the kinetic chain: The influence of the hip and foot on the patellofemoral joint Chapter 8: Conclusion – Have we solved the mystery? MikeReinold.com OnlineKneeSeminar.com © Copyright Mike Reinold, All Rights Reserved. This eBook is one of our free downloads for newsletter subscribers available at MikeReinold.com MikeReinold.com - Page 2 Want to Learn Exactly How I Evaluate and Treat the Knee? Take Your Knowledge of the Knee to the Next Level. Let Lenny Macrina and I walk you through a detailed online program designed to enhance your clinical examination and treatment skills. We’ll share with you the evidence-based scientific and clinical rationale behind what you need to know to make an immediate impact on your ability to work with knee patients. This is exactly how we evaluate and treat the knee. The course covers: • Clinical Evaluation of the Knee - An overview of our complete approach to the clinical examination of the knee. We'll cover the entire evaluation process from the subjective examination to a wide range of special test for ligamentous, meniscal, and patellofemoral pathology. • Treatment Progressions for the Knee - We'll demonstrate our treatment progressions for the knee joint complex designed to enhance neuromuscular control. We'll show progressions from early to advanced phases of rehabilitation using our 4 phase approach to restore baseline proprioception, dynamic stabilization, neuromuscular control, and functional movements. • Anterior Cruciate Ligament - An overview of the entire rehabilitation process following ACL reconstruction, including variations based on graft selection and specific patient criteria. • Patellofemoral - How to develop treatment programs for patellofemoral pain based on our patellofemoral classification system. Using this approach you'll be able to easily distinguish between many different reasons behind patellofemoral pain and treat appropriately. • Meniscus - We'll discuss meniscal pathology and the rehabilitation process of meniscal injuries, both nonoperatively as well as postoperative meniscectomy and meniscal repair procedures. • Articular Cartilage - The principles rehabilitation of articular cartilage injuries, including postoperative rehabilitation following microfracture, osteochondral autograft transplantation (OAT), and autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) procedures. • Osteoarthritis - The principles behind rehabilitation of the knee with osteoarthritis, including nonoperative management and rehabilitation following tibial osteotomy and total knee replacement surgery. Plus, the program has been approved for 22.5 contact hours of CEU credit through the NATA and for 18 CCUs through the FSBPT for 28 states. • Click here to learn more at OnlineKneeSeminar.com MikeReinold.com - Page 3 Chapter 1 Solving the Patellofemoral Mystery Welcome to my eBook dedicated to evaluating and treating the patellofemoral joint. Disorders of the patellofemoral joint continue to present as some of the most perplexing pathological conditions in orthopedics and sports medicine. Previously described as the “black hole of orthopedics” by Dr. Scott Dye, the patellofemoral joint continues to cause dysfunction for patients and confusion for clinicians. Patellofemoral pain syndrome is often described as a diagnosis that tends to result in poor outcomes. Despite years of research and attention to the joint, the vague use of the term “patellofemoral pain syndrome” continues to be prevalently abused used to categorize patients. This becomes evident when analyzing the myriad of surgical and rehabilitative interventions that are currently being utilized to alleviate symptoms and restore function in patellofemoral patients. It appears that a single surgical or rehabilitative approach cannot be efficaciously used to treat patellofemoral disorders. In this eBook, we will discuss the evaluation and treatment of the patellofemoral joint with topics ranging from differential diagnosis to treatment strategies that can be applied to any rehabilitation or fitness program. My goal will be to develop an easy to understand and implement system to treat patellofemoral pain based on an accurate differential diagnosis and an understanding of the normal biomechanics of the joint. Throughout this ebook there will be several links to references on the internet, anytime you see a blue underlined word or phrase, you can click that for more information. I hope you enjoy this eBook and look forward to seeing you online soon! Best, Mike Reinold, PT, DPT, SCS, CSCS MikeReinold.com - Page 4 Chapter 2 The Source of Patellofemoral Pain Patellofemoral disorders are often considered the most common knee pathology encountered by orthopedic and sports medicine clinicians. Some sources say that in the general population, 1 out of 4 will likely experience patellofemoral symptoms at some time in their life. Although patellofemoral disorders What Causes represent a common pathology, there is no consensus on Patellofemoral Pain? the optimal management of this condition. This may be explained, in part, due to the various sources of pain that may be contributing to the disorder. Unfortunately, terms such as “anterior knee pain” and “patellofemoral pain” have become accepted diagnoses with treatment often implemented without clear definitions of the underlying pathophysiology. The common use of such ambiguous and non-specific terms only adds to the confusion regarding optimal care for these patients. Rehabilitation programs designed for the patellofemoral patient must match the specific disorder and dysfunction. Chapter 4 of this series will discuss the differential diagnosis of patellofemoral pain, however it is important to understand the source of patellofemoral pain in addition to any possible diagnosis. In recent years, several authors have attempted to provide an explanation for the potential source of patellofemoral pain. Dye et al (AJSM 1998) examined the conscious neurosensory mapping of the lead author’s knee during arthroscopy without intraarticular anesthesia (This in itself is an amazing study, he literally had his partner scope his own knee without anesthesia!). The authors rated the level of conscious awareness from no sensation to severe pain. These findings were further subdivided based on the ability to accurately localize the sensation. Palpation to the anterior synovial tissues, retinaculum, fat pad and capsule produced moderate to severe pain that was accurately localized. The insertion sites onto the tibia and femur of the cruciate ligaments produced poorly localized moderate to severe pain. Slight to moderate poorly localized sensation was produced at the capsular margins. No sensation was detected on the patellar articular cartilage even though asymptomatic grade II and III chondromalacia was noted on the central ridge the patella. MikeReinold.com - Page 5 Within the clinical setting, patients often complain of diffuse patellofemoral pain while undergoing physical examination. The results of this study may provide an explanation for the vague description of pain that is often reported by patellofemoral patients; the majority of structures palpated produced poorly localized sensation. The implications of this are interesting. It appears that degenerative changes to the patellofemoral joint, or chondromalacia, was not a source of pain. The author/subject didn’t even know his patella had degenerative changes. Numerous authors (Chrisman OD: Clin North AM 1986, Dye SF: Orthop Clin North AM 1986, Fulkerson: Disorders of the Patellofemoral Joint 2004) have also documented that patellofemoral chondromalacia does not necessarily produce patellofemoral pain. Based on the results of these studies, it appears that the majority of patellofemoral symptoms may be originating from the anterior synovial tissues, retinaculum, fat pad and capsule, rather than from degeneration of the patellofemoral articular surfaces. It appears that the majority of patients complaining of patellofemoral pain may originate from the surrounding soft tissues and not from the osseous or articular cartilage structures. Furthermore, several authors have also postulated that patellofemoral pain may originate in the lateral retinacular soft tissues. Fulkerson et al (Clin Orthop 1985) performed a histological analysis on lateral retinacular and underlying synovial tissue of patellofemoral patients biopsied during lateral retinacular releases. These biopsies were compared to cadaveric specimens and biopsies taken from asymptomatic, non-patellofemoral patients undergoing surgery to address anterolateral rotary instability. Nerve fibers originating in the lateral retinaculum appeared enlarged with moderate lose of myelinated fibers in the patellofemoral patient. The authors state that nerves within the retinaculum may degenerate from the chronic stretching associate with muscular imbalances around the patellofemoral joint and present as a potential source of patellofemoral pain. MikeReinold.com - Page 6 Sanchis-Alfonso et al (AJSM 1998) biopsied the lateral retinaculum of patients undergoing a lateral retinacular release to address patellofemoral complaints. The authors found neuromas within the biopsied tissues similar to the results of Faulkerson et al (Clin Orthop 1985). The authors reported a direct relationship between the severity of pain and the severity of neural damage within the lateral retinaculum; patients presenting with moderate to severe complaints of pain were found to have the highest number of nerves and neural area. These findings were further supported in a follow-up study by Sanchis-Alfonso and Rosello-Sastre (AJSM 2000). The authors repeated the prior experiment, noting similar results with the additional finding of increased levels of substance P within the lateral retinaculum of patellofemoral patients. Thus, it appears that the source of pain in patellofemoral patients is multifactoral, with the surrounding soft tissues showing evidence of localized pain perception and neural adaptations that appear to contribute to the source of patellofemoral pain. MikeReinold.com - Page 7 Chapter 3 Differential Diagnosis of Patellofemoral Pain In 1998, one of the most influential rehabilitation publications of the last 2 decades was published on treatment of the patellofemoral joint. Four of the leaders and pioneers of sports medicine and orthopedic rehabilitation – Kevin Wilk, George Davies, Bob Mangine, and Terry Malone - teamed up to develop a classification system for the differential diagnosis of patellofemoral pathologies. This manuscript was the first to offer treatment strategies based on specific diagnoses for patellofemoral pain. Today, this manuscript still holds extreme value and if you haven’t read it, I highly recommend finding a copy. By far the most critical component of treating the patellofemoral joint is an accurate diagnosis. I will always challenge me students in this regard – find the cause of their symptoms and STOP using “patellofemoral pain” as a diagnosis. At first this can seem like a daunting task as the true source of patellofemoral pain can be misleading. However, using a classification system to group types of diagnoses can be extremely helpful in the formation of your treatment program. Classification of Patellofemoral Pain Patellar Compression Syndromes Patellar compressive syndromes are described as pathologies involving excessive compression between the patella and the trochlea due to tight surround soft tissue. These can result in significant changes to the articular surfaces of the patella and trochlea over time. This can be broken down into two distinct types of compression syndromes: Excessive lateral pressure syndrome (ELPS). ELPS was originally described as occurring when the patella is overconstrained by soft tissue tightness, specifically the lateral retinacular tissue. The patient will exhibit a lateral tilted and/or shifted patella and decreased medial glide. There is often times medial discomfort as MikeReinold.com - Page 8 the medial retinacular tissue is stretched due to a laterally displaced patella. I often find palpating the medial patellofemoral ligament elicits a decent amount of discomfort. I believe proximal and distal influences in the kinetic chain also effect the alignment of the patellofemoral joint and can cause an ELPS-like syndrome, though through a different mechanism. This should be assessed and is discussed more below. Global patellar pressure syndrome (GPPS). GPPS occurs when there is a general and diffuse medial and lateral soft tissue tightness that results in the patella being excessively compressed within the throclea. This is more commonly see after direct trauma, immobilization due to fracture, or knee surgery with the development of arthrofibrosis. Have you ever had a patient lose patella mobility after an ACL reconstruction? This is a good example of GPPS. These patients may also have decreased superior patellar mobility as the knee is immobilized in flexion. Patellar Instability On the other side of the spectrum is patellar instability, which can range from an acute dislocation to recurrent instability. On examination, patients will have excessive patellar mobility laterally. This is often associated with a shallow trochlea, so many patients may be predisposed to this condition. I would suspect this with the patient with chronic subluxations. Also, acute episodes of subluxation or dislocation may result in rupture of the medial patellofemoral ligament and subsequent medial pain. Patients with chronic subluxation usually don’t have as much sensitivity medially as their tissue adapts and/or tears over time. MikeReinold.com - Page 9 Try this – perform patellar gliding at 0 degrees of flexion and then again at ~30 degrees of flexion. If the patella continues to have excessive gliding at 30 degrees, then they likely have a shallow trochlea and poor static stability. These patients are challenging to treat as the static stability is a primary cause of their symptoms. Biomechanical Dysfunction The knee appears to take a good amount of stress when biomechanical faults are present both proximally and distally within the kinetic chain. Alterations in foot and ankle mechanics, hip strength, leg length discrepancy, flexibility deficiencies, and any combination of these factors can have a negative impact on the forces observed at the patellofemoral joint. Not only can biomechanical dysfunction lead to increased stress, it can also lead to chronic adaptations over time. Take for example someone with weak hip external rotation. This could lead to a dynamic inability to control the hip adduction and IR moment at the knee and cause the femur to rotate into internal rotation during activities. This will cause the patella shift laterally and can cause articular cartilage and soft tissue changes that will mimic a typical ELPS patient. You can loosen up the lateral soft tissue but without treating the true cause, the hip weakness, symptoms will continue to occur. This will be discussed in greater detail in a later chapter as this is an important factor to consider. Direct Patellar Trauma This is my least favorite pathology as I seem to always be a victim of direct patellar trauma myself. Have you ever hit your knee against a table leg? Every time I do, and it seems frequent, I think of the acute trauma my articular cartilage just took! This is also seen with patients falling on their knee, which is common up here in the northeast during the winter when it gets icy. Subjective exam should lead you this way, but you may have to MikeReinold.com - Page 10 probe, sometimes patients will forget that they fell 3 weeks ago or not correlate their symptoms with the incident. Patients in this classification can include bone bruises, articular cartilage lesions, and even fractures. Soft Tissue Lesions There are a few common soft tissue lesions that can occur to the patellofemoral joint. Accurate diagnosis of these syndromes usually involves direct palpation to these areas and a certain mechanism of trauma to the area. Suprapatellar plica syndrome. The plica is an interesting and debatable structure. I have always been of the belief that plica is very individual and some people have larger synovial folds than others. Most common is the suprapatellar plica, which is located medial and superior to the patella. This structure gets tight against the femoral condyle as the knee flexes so repetitive activities such as bike riding can cause this. IT band friction. Similarly, ITB friction can occur laterally as the patellar tract of the IT band gets taught against the lateral femoral condyle during flexion. Fat pad syndrome. The fat pad of the knee is highly vascularized and has rich nerve fibers. When a patients falls on their knee, they may inflame this structure. You can easily palpate on either side of the patellar tendon and find discomfort. Be sure to assure that you are not palpating the patellar tendon as treatment for this will vary. Medial patellofemoral ligament injury. This was previously discussed above, but realize that any issues with chronic ELPS or patellar instability will cause MPF ligament pathology. MikeReinold.com - Page 11 Overuse Syndromes Overuse syndromes include patellar tendonitis and less commonly quadriceps tendonitis superiorly. Patellar tendonitis most commonly occurs at the inferior pole of the patella, but may also occur midtendon or at the tibial tuberosity. Patients will present with typical symptoms of a tedonopathy. Two types of apophysitis can occur in the knee. These are common in adolescents during growth spurts and in athletes participating in jumping sports. These can easily be palpated and may be seen I’m not a big fan of naming things after people as they don’t offer any description of what the pathology is so I will use two versions of the terminology. • • Traction apophysitis of the tibial tuberosity (Osgood-Schlatter). Traction apophysitis of the inferior patellar pole (Sindig-Larsen-Johansson). As you can see, there are many different pathologies that can occur to the patellofemoral joint. The above list is not intended to be all-encompassing, but rather to create categories of diagnoses that share similar treatment guidelines. There are other potential source of PF issues, including neurologic origins from the lumbar spine or reflex sympathetic dystrophy, however I wanted to keep this discussion orthopedic. Once I rule out orthopedic issues I will explore other origins and a likely referral back to the doctor or specialist. To vaguely classify each patient as “patellofemoral pain syndrome” would be doing a disservice to the patient and will likely not result in optimal outcomes. A clear and accurate differential diagnosis is by far the most important aspect of treating the patellofemoral joint. Next time a patient comes to you with a referral stating “PFPS” or “anterior knee pain,” I challenge you to attempt to classify the patient appropriately. Treatments will vary greatly for each diagnosis. These will be discussed in a future post. Wilk KE, Davies GJ, Mangine RE, Malone TR. (1998). Patellofemoral disorders: a classification system and clinical guidelines for nonoperative rehabilitation. JOSPT DOI: 9809279 MikeReinold.com - Page 12 Chapter 4 Principles of Patellofemoral Rehabilitation Although the key to successful rehabilitation program for patellofemoral pain requires an accurate differential diagnosis, there are several principles to patellofemoral rehabilitation that should be considered when designing any program. Below are what I would consider the 10 key principles of patellofemoral rehabilitation. They can be used as a backbone to many programs and customized based on the specific diagnosis. 1. Reduce Swelling The first principle of patellofemoral rehabilitation is the reduction of swelling. Patellofemoral patients often present with joint effusion following injury and postoperatively. Chronic edema may also exist due to repetitive microtrauma of the soft tissues surrounding the patellofemoral joint. Numerous authors have studied the effect of joint effusion on muscle inhibition. DeAndrade et al (JBJS 1965) were the first to report in the literature that joint distention resulted in quadriceps muscle inhibition. A progressive decrease in quadriceps activity was noted as the knee exhibited increased distention. Spencer et al (Archive Phys Med Rehab 1984) found a similar decrease in quadriceps activation with joint effusion. The authors reported the threshold for inhibition of the vastus medialis to be approximately 20-30ml of joint effusion and 50-60ml for the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis. This is really not a lot of fluid, so any amount of effusion is significant. An unpublished study by Bob Mangine in the 1990’s showed that just a 30-40ml increase in fluid to the knee resulted in almost a 50% drop in quadriceps peak torque. The reduction in knee joint swelling is crucial to restore normal quadriceps activity. Treatment options for swelling reduction include cryotherapy, high-voltage stimulation, and joint compression through the use of a knee sleeve or compression wrap. I personally really like the Bauerfeind knee sleeves for knees that have some effusion. In patients who have undergone a lateral retinacular release, a foam wedge shaped to form around the lateral patella can be utilized in conjunction with a wrap to provide patella medialization and increased compression around the lateral genicular artery. I would not hesitate to use a knee sleeve or compression wrap to apply constant pressure while performing everyday activities in an attempt to minimize the development of further effusion. 2. Reduce Pain MikeReinold.com - Page 13 The second principle of patellofemoral rehabilitation is the reduction of pain. Pain may also play a role in the inhibition of muscle activity observed with joint effusion. Young et al (MSSE 1983) examined the electromyographic activity of the quadriceps in the acutely swollen and painful knee. An afferent block by local anesthesia was produced intraoperatively during medial meniscectomy. Patients in the control group reported significant pain postoperatively and pronounced inhibition of the quadriceps (30-76%). In contrast, patients with local anesthesia reported minimal pain and only mild quadriceps inhibition (531%). Pain can be reduced passively through the use of cryotherapy and analgesic medication. Immediately following injury or surgery, the use of a commercial cold wrap, such as a DonJoy Iceman, can be extremely beneficial. Passive range of motion may also provide neuromodulation of pain during acute or exacerbated conditions. Various other therapeutic modalities such as ultrasound and electrical stimulation may also be used to control pain via the gate control theory if that is your belief. 3. Restore Volitional Muscle Control The next principle involves reestablishing voluntary control of muscle activation. Inhibition of the quadriceps muscle is a common clinical enigma in patellofemoral patients, especially in the presence of pain and effusion during the acute phases of rehabilitation immediately following injury or surgery. Electrical muscle stimulation and biofeedback are often incorporated with therapeutic exercises to facilitate the active contraction of the quadriceps musculature. Snyder-Mackler et al (JBJS 1991) examined the effect of electrical stimulation on the quadriceps and musculature during 4 weeks of rehabilitation following ACL reconstruction. The authors noted that the addition of neuromuscular electrical stimulation to postoperative exercises resulted in stronger quadriceps and more normal gait patterns than patients exercising without electrical stimulation. Delitto et al (PT 1988) and Snyder-Mackler et al (JBJS 1995) reported similar results of both the quadriceps and hamstrings using electrical stimulation for a 3-week and 4-week, respectively, training period following ACL reconstruction. The use of electrical stimulation and biofeedback on the quadriceps musculature appears to facilitate the return of muscle activation and may be valuable additions to therapeutic exercises. Clinically, I use electrical stimulation immediately following injury or surgery while performing isometric and isotonic exercises such as quadriceps sets, straight leg raises, hip adduction and abduction, and knee extensions. I also use this as a maintenance program with many of my athletes with chronic knee issues. MikeReinold.com - Page 14 4. Emphasize the Quadriceps The next principle of patellofemoral rehabilitation is to strengthen the knee extensor musculature. Some authors have recommended emphasis on enhancing the activation of the VMO in patellofemoral patients based on reports of isolated VMO insufficiency and asynchronous neuromuscular timing between the VMO and VL. While the literature offers conflicting reports on selective recruitment and neuromuscular timing of the vasti musculature, the VMO may have a greater biomechanical effect on medial stabilization of the patella than knee extension due to the angle of pull of the muscle fibers at approximately 50-55 degrees. Wilk et al(JOSPT 1998) suggest that the VMO should only be emphasized if the angle of insertion of the VMO on the patella is in a position in which it may offer a certain degree of dynamic or active lateral stabilization. As you can see by the figure, if the fibers are not aligned in a position to assist with patellar stabilization, VMO training will likely not be effective. This orientation of the muscle fibers will differ from patient to patient and can be visualized. Several interventions and exercise modifications have been advocated to effectively increase the VMO:VL ratio, based mostly on anecdotal observations. These include hip adduction, internal tibial rotation, and patellar taping and bracing. Powers(JOSPT 1998) reports that isolation of VMO activation may not be possible during exercise, stating that several studies have shown that selective VMO function was not found during quadriceps strengthening exercises, exercises incorporating hip adduction, or exercises incorporating internal tibial rotation. Powers also states that although the literature offers varying support for VMO strengthening, successful clinical results have been found while utilizing this treatment approach. My belief is that quadriceps strengthening exercises should be incorporated into patellofemoral rehabilitation programs. Strength deficits of the quadriceps may lead to altered biomechanical properties of the patellofemoral and tibiofemoral joints. Any change in quadriceps force on the patella may modify the resultant force vector produced by the synergistic pull of the quadriceps and patellar tendons, thus altering contact location and pressure distribution of joint forces. Furthermore, the quadriceps musculature serves as a shock absorber during weightbearing and joint compression, any MikeReinold.com - Page 15 abnormal deviations in quadriceps strength may result in further strain on the patellofemoral and/or tibiofemoral joint. In reality, I believe that quadriceps strengthening is very important for patellofemoral rehabilitation, but many exercises designed to “enhance VMO” strength or activation may actually be disadvantageous to the joint. Take for example the classic squeezing of the ball during closed kinetic chain exercises such as squatting and leg press. This creates an IR and adduction moment at the hip that is now known to be detrimental to patellofemoral patients. I would actually propose that we work on quadriceps strengthening without an adduction component and rather emphasize hip adbuction and external rotation. This can be performed with the use of a piece of exercise band around the patient’s knees during these exercises. We will get into this in more detail in an upcoming post in this series. 5. Control the Knee Through the Hip Again, I don’t want to get to much into this as we will spend an entire chapter on this topic, but the importance of hip strength cannot be overlooked. Every patellofemoral patient should be assessed for hip weakness and poor dynamic control of their knee during functional activities. You will be shocked at how many of your patients have absolutely no strength outside of the sagittal plane. It is amazing. Emphasize the hip’s ability to eccentrically control the valgus moment at the knee produced by hip IR and adduction. I can’t say it enough, work on hip abduction and ER. This tip alone will greatly enhance your patellofemoral outcomes. More on this in an upcoming chapter. 6. Enhance Soft Tissue Flexibility Another principle of patellofemoral rehabilitation is the enhancement of joint flexibility with emphasis on quadriceps, hamstrings, hip adductors, gastrocnemius, and iliotibial band stretching. Any deficit in flexibility of these areas will cause significant biomechanical faults throughout the kinetic chain. Rehabilitation should focus on restoring full passive knee extension initially to minimize the development of a flexed knee posture exhibited by some patients with patellofemoral disorders. Ambulating and performing daily activities with a knee flexion contracture may result in increased patellofemoral joint reaction forces and requires a great deal of motor control to stabilize the knee joint. Full passive knee extension is important for improved quadriceps activity and also allows the knee to lock out while standing, thus allowing relaxation of the surrounding musculature. MikeReinold.com - Page 16 Restoring full knee flexion is also a significant priority. In postoperative patients, knee flexion is gradually restored especially in the presence of an effusion. In non-operative patients, knee flexion is gradually restored through controlled stretching exercises. The goal of restoring full knee flexion is not merely reestablishing quadriceps flexibility but improving soft tissue flexibility of the retinacular tissues as well. Witvrouw et al (AJSM 2000) prospectively studied the risk factors for the development of anterior knee pain in the athletic population over a 2-year period. A significant difference was noted in the flexibility of the quadriceps and gastrocnemius muscles between the group of subjects that developed patellofemoral pain and the control group, suggesting that athletes exhibiting tight musculature may be at risk for the development of patellofemoral disorders. 7. Improve Soft Tissue Mobility Soft tissue mobility is another rehabilitation principle that must be addressed. The goal of rehabilitation is to restore the soft tissue flexibility of the medial and lateral retinacular and capsular tissues. This may assist in controlling patellofemoral joint reaction forces by balancing the soft tissue pliability medially and laterally, and by correcting a possible tilt or rotation of the patella. Additionally, patellar mobilization techniques should be utilized to restore superior and inferior patellar mobility as well. Treatment techniques include patellar mobilizations and the application of patellar tape. While taping of the patella has received conflicting reports in the literature regarding its efficacy for correcting biomechanical deficits of the patella, taping may assist in restoring soft tissue flexibility by providing a low-load prolonged stretch of the retinacular tissues. Study after study shows that tape does not impact patella position or tracking (don’t get me wrong there are some that show that it does, but there are more that says tape does not). My personal belief is that this is the reason for a reduction in symptoms with the application of tape. Remember that the source of patellofemoral pain may not be from the articular cartilage but rather from the retinacular tissue. The utilization of a brace which imparts a medial glide or force to the patella may also be beneficial. There are many on the market and I truly have no preference at this time. It seems like a new and MikeReinold.com - Page 17 improved brace comes out every 6 months. Preliminary MRI studies have documented the effectiveness of bracing. 8. Enhance Proprioception and Neuromuscular Control Rehabilitation programs must also include drills designed to restore proprioceptive and neuromuscular control skills in patellofemoral patients. Proprioception and postural balance training begins immediately postinjury or postoperatively. Specific drills initially include weight shifting side-to-side, weight shifting diagonally, mini-squats, and mini-squats on an unstable surface such as a tilt board. As the patient advances, tilt board squats can be progressed from double leg to single leg. Perturbations can further be added to challenge the neuromuscular system. Initially, the clinician can apply manual perturbations. As the patient sustains a vertical squat on a tilt board at 30 degrees of knee flexion, the clinician adds perturbations by tapping the board with his or her foot. Ball tosses can be incorporated with manual perturbations to provide additional challenge. The patient progresses to perform a vertical squat to 30 degrees of knee flexion while performing a chest-pass with a 3-5 pound weighted ball. The rehabilitation specialist continues to add manual perturbations by tapping the board. Ball throws are progressed from chest-passes to side-to-side throws, and then overhead soccer throws. Again, these exercises can be progressed from double-leg to single-leg stance to further challenge the patients neuromuscular control. Depending on their sport participation, jump and landing training may also be necessary to teach the athlete how to avoid detrimental positions. 9. Normalize Gait Gait training is also a critical component to patellofemoral rehabilitation. A variety of factors contribute to antalgic and inefficient gait patterns including joint effusion, pain, soft tissue tightness, and scar tissue formation. Strategies used to minimize the flexed knee gait pattern that is commonly exhibited by patellofemoral patients include minimizing joint effusion and enhancing sift tissue flexibility, particularly the hamstring and gastrocnemius musculature. Specific techniques include retrograde walking over cones. This particular exercise requires adequate quadriceps control and involves the patient ambulating while high stepping over successive cones. As the patient moves backward, the foot strikes the ground in a toe to heel pattern to produce an extension moment at the knee. MikeReinold.com - Page 18 10. Gradually Progress Back to Activities Lastly, as the patellofemoral patient progresses through the rehabilitation program, emphasis should shift towards functional activities that replicate activities specific to each patient. The rate of progression with functional activities is dictated by the patient’s unique tolerance to the activities. Exercise must be performed at a tolerable level without overstressing the healing tissues. Pathological loading that produces detrimental stress on the patellofemoral joint should be avoided to prevent exacerbations of symptoms. Functional stresses are gradually increased leading to a steady return to function. The functional progression of activities should follow a progressive and sequential order to ensure proper amounts of stress are applied to facilitate healing without producing disadvantageous forces. MikeReinold.com - Page 19 Chapter 5 Specific treatment guidelines for patellofemoral pain Now that we have spent some time discussing the differential diagnosis of patellofemoral pain and principles of patellofemoral rehabilitation, we can move on to discussing specific treatment strategies for each of the differential diagnoses we previously discussed. If you have not read chapter 3 of this series on the classification of patellofemoral pain, you may want to go back as the following suggestions are based on that information. Remember, if you take one thing away from this eBook, treatment should be based on an accurate diagnosis! Diagnosing someone with patellofemoral pain syndrome is like giving up and saying you don’t know what is wrong with the patient! Specific Treatment Based on an Accurate Diagnosis Patellar Compression Syndromes In general, the main goals of treating a patient with a compression syndrome is to loosen the restrictions and minimize the subsequent inflammation. These are the patients that respond well to what I call a “loss of motion” protocol: Heat/whirlpool to warm up the tissue and prepare for treatment Continuous ultrasound to tight area. We can argue about the efficacy of US but I think this is a good time for it’s use. I am aggressive - continuous, jack it up to 2.0 and keep the area small, of course use patient tolerance as a guideline! Soft tissue massage progressing to aggressive massager or friction as inflammation subsides. Specific trigger point and muscle energy techniques can be helpful as well, especially in the patient with tight hips that are contributing to ELPS. MikeReinold.com - Page 20 Patellofemoral joint mobilization in whatever direction is needed For a patient with ELPS, I would consider trying patellar taping. I don’t use this to really change the alignment or biomechanics of the patellofemoral joint, study after study shows this does not happen with tape. I do however believe that the tape can be applied to potentially cause a low-load, long-duration stretch of the soft tissue/retinaculum around the knee. Remember, that stress and tension of the surround tissue may be the cause of patellofemoral pain. Generalized stretching of the lower extremity with specific emphasis on tight structures impacting the PF joint (i.e. the IT band). As with anything else related to the patellofemoral joint, look at the hip and foot to see if any biomechanical factors are contributing to lateral tightness of the knee. There are also some things that should be avoided in these patients: Bike riding – it is just going to compress the PJ joint and cause more symptoms Exercises with high PF joint reaction forces, such as knee extension. Again, just going to cause more compression and more irritation. In the patient with global compression syndrome, I would recommend you avoid taping. Again, just going to cause undue compression. In general, I would be conservative in strengthening exercises for the global compression patient. Straight leg raises, pool work, and other basic exercises should be enough while you loosen up the soft tissue. Patellar Instability The treatment for patellar instability depends on the chronicity of symptoms. For acute episodes, treatment will revolve around the “damage control,” or settling down the acute effusion and trauma associated with the incident. For the later phases of acute instability or those with chronic recurrent instability, we are basically dealing with a lack of “static” stability from the osseous and ligamentous structures of the knee. Thus, treatment should focus on enhancing stability in two ways: MikeReinold.com - Page 21 Enhance static stability. If this is an anatomical issue, this may be difficult if not impossible. This is the perfect patient for a patellofemoral brace. While a general donut knee sleeve or some of the older patellofemoral braces may be enough for some patients, there are a lot of newer and more advanced bracing. I have used the DonJoy Tru-Pull brace with success. What types of braces have you tried and preferred? Enhance dynamic stability. This is the general long term goal for these patients. It starts with enhancing strength and progresses to neuromuscular control exercises. This in itself is a lengthy topic, but I recommend you check out a DVD of the principles of neuromuscular control during knee treatment that Kevin Wilk and I have produced (more information here from AdvancedCEU). This will include dynamic stability of the entire lower extremity as any weakness in the kinetic chain could cause an excessive lateral stress on the patellofemoral joint. More to come on this in a future chapter in this eBook. Biomechanical Dysfunction As previously stated in my post on the classification of patellofemoral pain, the knee appears to take a good amount of stress when biomechanical faults are present both proximally and distally within the kinetic chain. Alterations in foot and ankle mechanics, hip strength, leg length discrepancy, flexibility deficiencies, and any combination of these factors can have a negative impact on the forces observed at the patellofemoral joint. Not only can biomechanical dysfunction lead to increased stress, it can also lead to chronic adaptations over time. Take for example someone with weak hip external rotation. This could lead to a dynamic inability to control the hip adduction and IR moment at the knee and cause the femur to rotate into internal rotation during activities. This will cause the patella shift laterally and can cause articular cartilage and soft tissue changes that will mimic a typical ELPS patient. You can loosen up the lateral soft tissue but without treating the true cause, the hip weakness, symptoms will continue to occur. This will be discussed in greater detail in a future chapter in this eBook as this is an important factor to consider. MikeReinold.com - Page 22 Direct Patellar Trauma Ouch, I hate even thinking about direct patellar trauma. My knee hurts just thinking of it! With this pathology, we are worried about either a patellar fracture or articular cartilage damage. Once the initial trauma subsides, treatment should attempt to enhance cartilage healing. This means frequent ROM of the knee. In addition to standard PROM, this can be in the form of a bike, if minimal resistance is applied. You do not want to compress too much but a little bit of motion is better for cartilage healing. I also like the pool for these patients if possible. You’ll have to limit patellofemoral joint reaction forces with exercises but this should subside with time. If symptoms do not resolve, the patient should be sent back to their doctor for further evaluation to rule out a fracture or an OCD type cartilage lesion. Soft Tissue Lesions Treatment of soft tissue lesions to the plica, IT band, fat pad, or medial patellofemoral ligament involves an understanding of the basic principles of patellofemoral pain rehabilitation, but there are a few things to consider as well. In general, you should stop the activity that is causing the irritation and avoid direct pressure on that area, so no transverse friction massage initially. This may be appropriate when chronic to stimulate healing, but in my experience this tends to make things worse for soft tissue lesions. I have found that direct anti-inflammatory modalities, such as an iontopatch, is helpful for these superficial areas of inflammation. Other treatment strategies for specific lesions include: Suprapatellar plica syndrome. The plica will get stressed over the medial femoral condyle with knee flexion, so avoid activities with repetitive flexion, such as bike riding and running. IT band friction. Similarly to above but with the lateral femoral condyle. Lengthening massage to the IT band has been helpful in my practice. Fat pad syndrome. The patient should avoid excessive quadriceps activities, especially if this causes irritation to the fat pad as the patellar tendon can compress the area when contracting the quad. Medial patellofemoral ligament injury. These patients should actually have treatment similar to the ELPS patient above. A brace to control lateral patellar translation may be helpful too. MikeReinold.com - Page 23 Overuse Syndromes Overuse syndromes include tendonopathy to the patellar tendon, and less commonly quadriceps tendonitis superiorly, and apophysitis of the tibial tuberosity or inferior patellar pole. For tendonopathy, treatment begins with assessing the chronicity of symptoms. If acute, reduce inflammation and restore strength and flexibility. I hate to be vague, but I doubt you’ll see a lot of patients that are this acute. Realistically, people put off treatment for months and end up with chronic tendonosis. This is another lengthy topic, but the key here is that the patellar tendon is not actually inflamed, it is degenerative due to a lack of healing blood supply (that is why the surgery for this is debridement to stimulate healing). Thus, traditional treatment to reduce inflammation is not going to work. In a way, you need to induce a certain amount of trauma, such as with transverse friction massage. I also recommend that general orthopedic patients need to feel about a 3-4/10 on a pain scale during exercises to actually stimulate healing. Any less and you probably aren’t stressing the area enough and any more and you may overloading. Apophysitis of the tibial tuberosity or inferior patellar pole can be a pretty limiting pathology. The two best treatments are time and avoiding the activity that causes symptoms. That means many youth injuries will need to take some time off from basketball, or whatever may be causing their symptoms, as their body grows and the symptoms resolve. Treatment is basically to reduce symptoms, there isn’t much you can do to actually “heal” the injury. Now that we have discussed the basic principles of patellofemoral rehabilitation and some specific treatment guidelines for various diagnoses, you should have a good basis to improve the care of your patients. The principles discussed so far are extremely important to understand and apply to each patient to assure you are optimizing your treatments and enhancing your outcomes. The next two chapters in this eBook will take treatments one step further as we talk about the biomechanics of the patellofemoral joint during exercises and the influence of the kinetic chain on the patellofemoral joint. MikeReinold.com - Page 24 Chapter 7 Biomechanics of the patellofemoral joint – clinical implications As we continue our journey through the diagnosis and treatment of patellofemoral injuries, it is time to shift gears from the basic principles of care and discuss our final two topics – the biomechanics of the patellofemoral joint itself and the biomechanical influence of the kinetic chain on the patellofemoral joint. To me, these are two extremely important topics that are often not addressed as much as they should. Articulation of the Patellofemoral Joint The patella really is an amazing bone in our body. Did you realize that the artiuclar cartilage on the undersurface of the patella is the thickest in the body? That really is amazing and shows just how much force is applied to the joint. Take a look at the picture on the right, notice how thick the cartilage is in comparison to the bone? When rehabilitating a patient with a known lesion of the patellofemoral joint, it its important to understand the joint arthrokinematics. Articulation between the inferior margin of the patella and the femur begins at approximately 10 – 20 degrees of knee flexion. The patella does not articulate with the trochlea near terminal knee extension. As the knee proceeds into greater degrees of knee flexion, the contact area of the patellofemoral joint moves proximally along the patella and posterior along the condyles. MikeReinold.com - Page 25 This is an important concept to understand and emphasizes the importance of good communication between the physician and rehabilitation specialist. If we know the specific area of articulation, we can MikeReinold.com - Page 26 work around that area, otherwise we don’t know when a lesion will articulate and will have to be more conservative. Contact Area of the Patellofemoral Joint In addition to understanding when the patellofemoral articulates, it is important to discuss the area of contact. Obviously, contact between the patella and trochlea that covers a larger surface area will distribute the load over a greater area. This is a driving factor in exercise selection and will be talked about below. At 30 degrees, the area of patellofemoral contact is approximately 2.0cm2. The area of contact gradually increases as the knee is flexed. At 90 degrees of knee flexion contact area triples, increasing up to 6.0cm2. As you can see, The contact area initially is small and gradually increases as the joint become more congruent. Alterations in Q-angle are often associated with patellofemoral disorders and may alter the contact areas and thus the amount of joint reaction forces of the patellofemoral joint. Huberti and Hayes examined the in vitro patellofemoral contact pressures at various degrees of knee flexion from 20 – 120 degrees. Maximum contact area occurred at 90 degrees of knee flexion and was estimated to be 6.5 times body weight. A increase or decrease in Q-angle of 10 degrees resulted in increased maximum contact pressure and a smaller total area of contact throughout the range of motion. This information may be applied when prescribing rehabilitation interventions so that exercises are performed in ranges of motion that place minimal strain on damaged structures. MikeReinold.com - Page 27 Patellofemoral Joint Reaction Forces Patellofemoral joint reaction forces are observed during all movements of the knee. Often times, it is the goal of rehabilitation to exercise the lower extremity while minimizing patellofemoral joint reaction forces. Forces occur from a combination of: • • • Articulation and contact area Resultant force vector between the quadriceps and patellar tendon Muscle contraction We have already discussed the articulation and contact area. Again, joint forces are reduced when distributed over a large surface area. When we discuss lever arms, remember that the patella’s true function is to increase the mechanical advantage of the quadriceps muscle. Take a look at the diagram below, notice how the resultant force (red arrow) vector increases as the knee flexes and the line of pull from the quadriceps and patellar tendons causes a more compressive force? I wish it were that simple and we could say that joint reaction forces are always highest as the knee flexes. Unfortunately, we have to take muscle contraction into consideration as well. The quadriceps is designed to cause compression of the patellofemoral joint. The force of the quadriceps is greatest at terminal knee extension, that is why patients with patellectomies have such a difficult time extending their knees, they lost the biomechanical advantage of the patella and cannot produce enough quadriceps force to fully extend the knee. MikeReinold.com - Page 28 Now put the contact area together with the quadriceps force. The quadriceps provides the greatest compressive force near extension when the contact area of the patellofemoral joint is smallest. Thus, a high force on a small area produces considerable patellofemoral joint reaction forces. To demonstrate just how significant these forces are, take a look at the below table that I put together from various sources for a 200 pound person. Notice how deep squatting applies close to 4000 lbs of force to the patellofemoral joint (still want to squat?). Activity Force % Body Weight Pounds of Force Walking 850 N 1/2 x BW 100 lbs Bike 850 N 1/2 x BW 100 lbs Stair Ascend 1500 N 3.3 x BW 660 lbs Stair Descend 4000 N 5 x BW 1000 lbs Jogging 5000 N 7 x BW 1400 lbs Squatting 5000 N 7 x BW 1400 lbs 20 x BW 4000 lbs Deep Squatting 15000 N Biomechanics of Rehabilitation Exercises The effectiveness and safety of open kinetic chain (OKC) and closed kinetic chain (CKC) exercises have been heavily scrutinized in recent years. While CKC exercises replicate functional activities such as ascending and descending stairs, OKC exercises are often desired for isolated muscle strengthening when specific muscle weakness is present. Steinkamp et al analyzed the patellofemoral joint biomechanics during the leg press and extension exercises in 20 normal subjects. Patellofemoral joint reaction force, stress, and moments were calculated during both exercises. From 0 – 46 degrees of knee flexion, patellofemoral joint reaction force was less during the CKC leg press. Conversely, from 50 – 90 degrees of knee flexion, joint reaction forces were lower during the OKC knee extension exercise. Joint reaction forces were minimal at 90 degrees of knee flexion during the knee extension exercise. MikeReinold.com - Page 29 Escamilla et al observed the patellofemoral compressive forces during OKC knee extension and CKC leg press and vertical squat. Results were similar to the findings of Steinkamp et al; OKC knee extension produced significantly greater forces at angles less than 57 degrees if knee flexion while both CKC activities produced significantly greater forces at knee angles greater than 85 degrees. When analyzing the biomechanics of the OKC knee extension, remember the concept from above regarding the quadriceps force near extension. Grood et al reported that quadriceps force was greatest near full knee extension and increased with the addition of external loading. The small patellofemoral contact area observed near full extension, as previously discussed, and the increased amount of quadriceps force generated at these angles may make the patellofemoral more susceptible to injury. At a lower range of motion, the large magnitude of quadriceps is focused onto a more condensed location on the patella. My friend Rafael Escamilla has published a few new studies on patellofemoral joint forces during the lunge and squatting exercises. The first study, published in Clinical Biomechanics, demonstrated that the front and side lunge exercises showed the same pattern of force as the squatting and leg press, with more force the deeper the lunge. Interestingly, performing the lunge from a split-stance position (not actually striding to perform the lunge) also showed a decrease in force and should be used initially. His follow-up study demonstrated that a longer stride has less force than a shorter stride during the forward lunge. Escamilla also analyzed the patellofemoral joint reaction forces between the wall squat (performed with feet close to wall and far away from wall) and the single leg squat. Results indicate that the closer your feet are to the wall, the greater the force during the wall squat exercise. At deeper angles > 60 degrees, the wall squat produced greater force than the one legged squat. Interesting results that should be applied to our exercise prescription. Clinical Implications When applying the results of Steinkamp(38), Escamilla(39), and Grood(40), it appears that during OKC knee extension, as the contact area of the patellofemoral joint decreases the force of quadriceps pull subsequently increases, resulting in a large magnitude of patellofemoral contact stress being applied to a focal point on the patella. In contrast, during CKC exercises, the quadriceps force increases as the knee continues into flexion. However, the area of patellofemoral contact also increases as the knee flexes leading to a wider dissipation of contact stress over a larger surface area. Recently, Witvrouw et al (41) prospectively studied the efficacy of open and closed kinetic chain exercises during non-operative patellofemoral rehabilitation. 60 patients were participated in a 5-week exercise program consisting of either open or closed kinetic chain exercises. Subjective pain scores, functional ability, quadriceps and hamstring peak torque, and hamstring, quadriceps, and gastrocnemius flexibility were all recorded prior to and following rehabilitation as well as at 3 months proceeding. Both MikeReinold.com - Page 30 treatment groups reported a significant decrease in pain, increase in muscle strength, and increase in functional performance at 3 months following intervention. Thus it appears that the use of both open and closed kinetic chain exercises may be used to maximize outcomes for patellofemoral patients if performed within a safe range of motion. I prescribe the form of exercise based on the clinical assessment. If CKC exercises are less painful than OKC exercises, than that form of muscular training is encouraged. Additionally, in postoperative patients, regions of articular cartilage wear is carefully considered before an exercise program is designed. Most frequently, I’ll allow open kinetic exercises such as knee extension from 90 – 40 degrees of knee flexion. This range of motion provides the lowest amount patellofemoral joint reaction forces while exhibiting the greatest amount of patellofemoral contact area. Closed kinetic chain exercises such as the leg press, vertical squats, lateral step-ups, and wall squats (slides) are performed initially from 0 to 30 degrees and then progressed to 0 to 60 degrees where patellofemoral joint reaction forces are lowered. As patient symptoms subside, the ranges of motion that are performed are progressed to allow greater muscle strengthening in larger ranges. Exercises are progressed based on the patient’s subjective reports of symptoms and the clinical assessment of swelling, painful crepitus, and discomfort. MikeReinold.com - Page 31 Chapter 7 Understanding the clinical implications of the kinetic chain: The influence of the hip and foot on the patellofemoral joint The influence of the kinetic chain on the patellofemoral can not be underestimated. Because the knee is located mid-way through a weightbearing extremity, it is vulnerable to excessive force from biomechanical faults located both proximally and distally Remember: to the knee itself. Examination of the joints proximal and While forces from the foot and ankle have been distal to the knee is imperative in the associated with patellofemoral pain for some time now, treatment of patellofemoral pain. the influence of the hip is becoming more of a hot topic as research has demonstrated significant increases in forces and injuries originating from biomechanical faults associated with the hip. A particular pioneer in this research has been Dr. Christopher Powers from the University of Southern California. A Pubmed search on Dr. Powers reveals several significant papers on the topic, specifically one of my favorites from JOSPT on the influence of the kinetic chain on patellofemoral biomechanics. I believe a significant reason why “patellofemoral pain” has been such a challenging diagnosis in the past is because we are treating the symptoms, not the cause of the pain, which is many times may be coming from elsewhere within the kinetic chain. The Influence of the Hip on Patellofemoral Pain The influence of the hip on the patellofemoral joint has been well documented over the last decade. The biomechanical works of Dr. Powers have shown that excessive hip adduction and internal rotation places the patellofemoral joint in a disadvantageous position. Unfortunately, our population is dominated by sagittal plane strength and weakness in the coronal and transverse planes. It seems like it is a normal part of daily living now as the majority of our functional tasks take place in the sagittal plane. Even more unfortunate is the fact that exercises outside of the sagittal plane are often neglected in rehabilitation and strength training programs. This creates a significant biomechanical disadvantage. To fully understand the significance of this, imaging the weightbearing knee. When the hip moves into adduction and internal rotation while the foot is planted, the femur will change position around a relatively stable patella (there is movement, just using this as an example). It is the reverse concept that MikeReinold.com - Page 32 is commonly seen in patellofemoral rehabilitation. The movement, or “tracking” of the patella on the femur is less relevant in this weightbearing position. It is the movement of the femur on the patella that is significant. Below is an example of how the femurs moves on the patella in the weightbearing position, note the patella is fairly stable while the femur rotates internally: This is likely the mechanism of patellar subluxations and dislocations and the cause of wear and tear of the joint. Patients often describe an injury that occurs when planting and pivoting or planting on an unstable surface. The quadriceps contracts to stabilize the knee while the femur is adducted and internally rotated, resulted in a lateral displacement of the patella in relation to the femur. This can cause an acute injury as well as degeneration over time. A recent study by Dr. Powers in JOSPT showed that females with patellofemoral pain had greater hip rotation during running, jumping, and stepping down. This also lead to subsequent decrease in hip strength. In fact, another study by Dr. Powers’ group published in AJSM demonstrated that patellofemoral pain in women is the results of decreased hip strength not anatomical variations (wider hips, etc.). Treatment of these patients requires training the hip to abduct and externally rotate. Also, it is important to train the hip abductors and external rotators to isometrically stabilize the knee during sagittal plane movements and to eccentrically control hip adduction and internal rotation. A simple test I perform is the step-down exercise. I am specifically looking for the ability to eccentrically lower the body in the sagittal plane while preventing the hip from dipping into adduction and internal rotation. This is harder than it looks and will often be an issue in your patients. But trust me, overtime this will improve, and POOF! Your patient’s patellofemoral pain while climbing stairs and running will have vanished! You are a genius now, the last three times she went to rehabilitation elsewhere they MikeReinold.com - Page 33 perform ultrasound on her knee and had her squeeze a ball between her knees during mini-squats to “strengthen her VMO.” Which brings up a great topic, do you still want to squeeze that ball between your knees and emphasize hip adduction and internal rotation? I would actually recommend just the opposite. I frequently use a piece of Theraband (or even those new knee resistance straps that Theraband just started making) around the patient’s knees during exercise. This will require the patient to isometrically control the hip from adducting and internally rotating while performing mini-squats, wall squats, leg press, and other sagittal plane exercises The Influence of the Foot and Ankle of Patellofemoral Pain Just as forces located proximal to the knee can have a significant impact on the patellofemoral joint, forces distal to the knee may also contribute. Treatment for patellofemoral patients should include a thorough assessment of the foot and ankle to establish biomechanical factors that need to be addressed. Orthotic fabrication is often necessary, though off-the-shelf orthotics have had some success in the literature. Pronation. Excessive pronation of the foot causes a reciprocal internal rotation moment of the tibia. This turn increases the resultant Q-angle at the knee. As we previously discussed in our previous post on the biomechanics of the patellofemoral joint, an increased Q-angle will cause a greater amount of force on a more focal portion of the patella. Furthermore, an internal rotation moment of the tibia also results in internal rotation of the femur and a more laterally displaced patella. This may be a cause of ELPS as discussed previously when we discussed the differential diagnosis of patellofemoral pain. MikeReinold.com - Page 34 Leg Length Discrepancy. I chose to include leg length discrepancy with the group of distal forces as the impact of a longer leg length tends to impact the positioning of the foot and ankle. The longer leg will tend to have a toe-out and pronated position to compensate for the longer length. Supination. Patients labeled as “pronators” seem to get all the attention, but excessive supination is likely just as bad. Not only do you diminish the foot’s ability to dissipate force, supination will result in external rotation of the tibia and more force to the patella. You can see that the position of the foot and ankle when the foot hits the ground is important to evaluate as it will alter the arthrokinematics and patellofemoral joint reaction forces. It can not be stressed enough that it is imperative that the proximal and distal aspects of the kinetic chain need to be evaluated and treated in patients with patellofemoral pain. I am sure that your outcomes will begin to improve by not neglecting this important aspect of treatment. Powers CM (2003). The Influence of Altered Lower-Extremity Kinematics on Patellofemoral Joint Dysfunction: A Theoretical Perspective J Orthop Sports Phys Ther DOI: 14669959 MikeReinold.com - Page 35 Chapter 8 Have We Solved the Patellofemoral Mystery? Probably not, but although the patellofemoral joint may still be a complicated area of sports medicine, I hope that this eBook has helped take the some of the mystery out of patellofemoral pain. In putting the pieces of this series together, remember to: • • • • Understand the source of patellofemoral pain and realize it might not be from “chondromalacia.” Perform a thorough examination and attempt to identify a specific diagnosis, lets stop using the term “patellofemoral pain” and describe the actual diagnosis! Consider the basic principles of patellofemoral pain rehabilitation, including understanding the biomechanics of the joint and the biomechanics during exercise. Look proximal and distal within the kinetic chain to identify a potential true “source” of patellofemoral pain and stop treating the “symptoms!” MikeReinold.com - Page 36 OnlineKneeSeminar.com MikeReinold.com MikeReinold.com - Page 37