Unguistics: The Representationof Language

241

6.3 Syntax

SomePreliminaries

Languagesare cognitive systemsthat enablehumanbeings to expressan infinite range

of meaningsin a physical, (typically ) acoustic form. However, having investigated a

theory of phonological representation, we are still far &om an understandingof how

linguistic sounds are paired with semanticinterpretations. Indeed, one of the central

mysteriesof natural languagecan be couchedin this way : how is it that the movement

of air molecules, and attendant changesin pressure,can ultimately be treatedby human

beings as meaningful?

Obviously , meanings must be correlated with morphemes and words, but there

must also be a procedure for assigning meaning to phrases, sentences

, and larger

discourses. Current linguistic theory maintains that there is a highly articulated subcomponent

of grammars- the syntax- that mediatesthe pairing of sound and meaning

. As in the case of phonological theory (or, indeed, any currently developing

theory), there are a number of alternative approaches to the study of syntax. However,

to permit us to examine syntax in some depth, we will concentrateon the theory of

generative grammar currently being developed by Chomsky and others known as

Government and Binding (GB). (For referencesto and summariesof other approaches,

seeSells 1985 and Wasow 1989.)

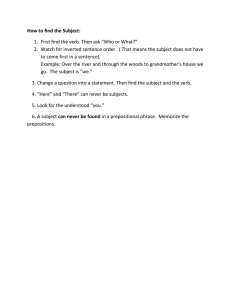

There are severalmotivations for positing a level of syntactic representation. Consider

a sentencelike Herb and Raewent to the beachin which there appearsto be an

intuitive boundary between the subject of the sentence, Herb and Rae, and the predicate

. The syntactic structure of the sentencecan be informally

, went to the beach

sketchedas follows:

(22)

[[Herb and Rae] [went to the beach]]

Sometimeswe have clear intuitions (introspective beliefs and judgments) about this

kind of structural categorization. Asking a native speakerto " divide a sentenceinto its

two main parts" will fairly reliably give the structure in (22). There is also considerable

experimental evidence within psycholinguistics to support the view that the mental

representationsof sentencesinvolve higher-order structure of this sort. Fodor, Bever,

and Garrett (1975) provide a good overview of these results. Levelt (1970), for instance

"

, showed that when subjects are asked to judge the " relative relatedness

of

adjacentwords in a sentence

, responsesshowing a high degree of relatednesscluster

around syntactic boundaries like those indicated in (22). In experiments using more

, Fodor and Bever (1965) inserted brief clicks into sentencesand

complex sentences

asked subjects to locate the noise. Subjects' performance was best when the click

coincided with a syntactic boundary.

In certain cases, however, our intuitions about syntactic structure are not always

clear and may be subject to disagreementamong speakers

. Moreover, we ought not

the

of

a

investigate

properties

languagesimply by asking speakersto tell us about its

structures. Although people often believe that they have insight into such matters, it

does not makefor good scienceto rely on the laypersons hunchesabout languageany

more than it would to employ suchan approachin the study of an organ like the brain,

or the mechanismsof visual perception.

Consequently, casesin which experimentalevidenceis unavailable, or in which we

may not yet know where to look for experimental confirmation, will require other

242

6

Chapter

. Fortunately, there

ways of establishingthe structure that we associatewith sentences

are tests that can be applied that provide linguistic evidence for assignedstructure.

tests.In this regard, considerthe following ambiguous

Among thesetools are constituency

sentence

, a casein which a single string of words can be assignedmore than one

semanticinterpretation.

(23)

The people talked over the noise.

This sentencemight be interpreted to mean that the people spoke so as to overcome

an interfering sound. In this casea plausible syntactic analysisof the sentencemight

be as in (24):

(24)

[ Thepeople] [talked [[over] [the noise]]]

Here, the verb is talked, and the rest of the predicateconsistsof a prepositional phrase

overthe noise(which in turn consistsof the preposition overand its object the noise

).

the

sentence

be

to

mean

that

the

discussed

,

Alternatively

might

interpreted

people

the noise. Under this interpretation, a reasonableconstituent analysismight look like

this:

(25)

[ Thepeople [[talked over] [the noise]]]

This analysisof (23) treats the verb ascomplex, consistingof the simpleverb talkedand

the particle over. But if this grouping is correct and the string talked over forms a

constituent (a structural unit), we should be able to substitute another verb for it - for

- and still have a sentencethat

instance, discussed

preservesthe same relationships

between structure and meaning. In the caseof (24), however, we cannot make such a

substitution. Instead, we can substitute a phraselike in spiteof the interruptionsfor over

the noise

, consistent with the claim that the latter constitutes a structural unit in (24)

(though not in (25 . We refer to this as the substitutiontest. In the caseat hand this test

reveals that a single sentencecan correspond to two quite different propositions,

eachof which has a distinct syntactic (and logical) structure, hence, a different cognitive

representation.

Additional confirmation for the conclusion that (23) can be associatedwith two

different syntactic representationscomesfrom considering the following example:

(26)

The people talked the noise over.

Notice that unlike (23), (26) can only mean that the people discussedthe noise,

and not that they overcame it. But why does the second meaning disappear? Our

explanation is that when (23) is structured as in (25), it can be transfonnedinto an

alternative representationin which the particle overappearsat the end of the predicate.

Other complex verbs such as call up and egg on also allow displacement of the

particle:

. +-+ The committeecalled

(27) a. The committee[calledup] the candidate

the candidateup.

b. The fans[eggedon] their opponents

. +-+ The fanseggedtheir

opponentson.

, however,do not allow a repositioningof the prepositionat the

Prepositional

phrases

endof the phrase

:

Linguistics: The Representationof Language

(28)

243

a. The man stood quietly [ behindthe tree]. .,t+ ~ e man stood

quietly the tree behind.

b. The duck worried about the football. .,t+ . The duck worried the

football about.

So, when (23) has the meaning and the structure of (25), over counts as a particle and

can be dislocated to the end of the predicate. This explains why (26) can carry the

meaning of (23) that is supported by (25). In contrast, when (23) has the meaning and

the structure of (24), over counts as a preposition. Sinceprepositions cannot dislocate

(see(28 , overcannot dislocatein this analysis. Thus, on its representationin (25), (23)

can be turned into (26), but not on its representationin (24). This provides a strong

argumentfor taking meaningto be assignedon the basisof syntactic structure, and not

directly to words and sentencesthemselves.By applying constituencytestssuchas the

substitution test and by examining distributional patterns in a language, linguists can

determine the nature of the syntactic structure.

We argued earlier that the inherent creativity of language, and the ability of the

human information-processingsystem to acquireand processit , cannot be explainedif

we view the language ability simply as a mental list of sentences

. Such a list of

sentenceswould need to be infinitely long, a fact at odds with the assumptionthat

all of our cognitive capabilitiesmust be representablewithin Anite-sized systems(our

brains). Our most recent considerationsadd a secondreasonto resist a conception of

- the

the languagefaculty as a list of sentences

interpretation of sentencesrequiresthe

assignmentof a particular syntactic structure. We have suggestedthat a more promising

conception of linguistic knowledge is that speakersknow the patterns of their

language, and that those patterns can be representedas a set of rules and principles

that define the infinitely large classof permissiblesentences

.

TheGoalsof a Grammar

What would an appropriateset of suchrules and principleslook like for a languagelike

English? To approach this question, consider first the simpler case of an abstract

formal languagethat consistsexclusively of sentencelikestrings containing any number

of instancesof the symbol "B " followed by a single occurrenceof the symbol " A ."

A grammar for this languagecontains the initial symbol " A ," and a rule that dictates

that the symbol " A " can dominate(consist of ) the string of symbols "B A " :

(29) A - + BA

The application of such a rule yields the string "B A " ; the symbol " A " dominatesthe

"

two symbols B A ," as the rule specifies(figure 6.16). Notice, however, that this rule

- it may

can apply recursively

. If we reapply the rule once,

reapply to its own output

"

"

"

the lower occurrenceof A will dominate the string B A ." If we reapply it twice, we

get the result shown in figure 6.17. There is, in fact, no limit to the number of times the

rule may be applied in a derivation.

A

1\A

B

Figure6.16

Treerepresentation

of a derivationemployingthe rule A -+ B A

Chapter 6

.m

244

Figure6.17

An exampleof a recursivederivatiol1

Supposewe considereachoccurrenceof a symbol that doesnot dominateany other

symbol a terminal element. The sequenceof terminal elements constitutes a wellformed string, or sentenceof the language. In the caseof figure 6.17, the sentencewe

have generatedis "8 B B A ." Sincethere is no upward bound on the number of times

that this rule can be recursively applied, there is an infinite number of sentencesin this

formal language. Accounts in current linguistic theory hold that the syntax of natural

languagescan be characterizedby a grammar that employs recursionin this senseto

provide for the essentialcreativity of linguistic systems.

Note that all the sentencesgeneratedby our simple grammar will be of the form

" "

"

"

" "

8I1A - some number n of 8 s followed by exactly one A . Any other string is

ungrammatical it is not a part of the language, and the grammar will not be able to

generate(assigna structure to ) it. The syntacticianundertakesto determinejust which

finite set of rules is adequateto the task of defining the syntactic patternsof a particular

language. The primary goal of syntactic theory &om the perspectiveof the cognitive

scientistis to model the systemof knowledge that determineswhich utterancesconstitute

the language, and to contribute to an explanation of how that knowledge is

acquiredand used.

As we have pointed out, the criterion of grammaticality is not to be found in

. We test claims about syntactic

grammar books, but in the judgments of speakers

structure and the adequacy of a particular hypothesis against data in the form of

intuitions of native speakers

. All speakersof English will , without hesitation, report

without a is not a sentenceof English. Neither

that the string .girl the the hippopotamus

is .girl the kissedboy the, even though we can make more senseof this string. Furthermore

, we can produce and understand a sentencelike Melvin ate a bulldozerthat he

believedwas trying to turn him into a watennelonand determine that it is grammatical,

in spite of the fact that it expresses a bizarre claim. Indeed, Chomsky (1957) observed

that a sentencelike Colorlessgreenideassleepfuriously is grammatical (that is, fits the

pattern of English) even though it is nonsensical.

'

Syntacticiansdo not ordinarily rely on the production of speakersactual utterances

in gathering their data. For one thing, speakersmay not necessarilyproduce the types

of sentencesthat we wish to investigateeven though they are within their grammatical

competence.For another, actualutterancesmay involve errors in perfonnance: shifts of

attention, limits on memory, drunkenness

, and so forth , can produce outputs that are

not actually consistentwith the grammar(and whose inconsistencyhasa different kind

of explanation).

Unguistics: The Representationof Language

245

S

~~~- - "'--~.."- "

'- ~,,- ,,

",- - ~", r

- -" NP

VP

TENSE

""

""""""""""""""

.............. , ............

...

..

/

...

"""

""'"

....

.............

I

/ /

,

DET

N

V

AP

PAST

I

the

I

dog

I

be

t

humble

Figure 6.18

Phrasemarker for the sentenceThedog was humble

As a result, we must provide a laboratory-like environment in which we arti6cially

induce the kind of linguistic behavior that we want to examine. Syntacticianstypically

' ' '

"

? is

; is . . . a grammatical sentence

proceed by asking questions of native speakers

normally all that is needed once a subject has a rough-and-ready understanding of

what is meant by grammaticality. By and large we can develop a substantialand highly

consistentbody of data in this fashion. We typically need not resort to more formal

experimentalprocedures, although in unclearcaseswe may well want to do so. In part,

this consistencyis achieved by investigating constructions that are sharedby many

speakersof a given dialect or language.

The Theoryof Grammar: PhraseStructure

We have already seen evidence that the syntacHc properHesof sentencescannot be

describedsolely in terms of linear sequencesof words. But linear order is an important

Hon of grammaHcality for many (though not all) languages. In

part of a characteriza

new

books

is

a

well -formed phrase, whereas. booksnew is not. By contrast, in

English

Sinhalapot alut- literally ' booksnew' - is grammatical, but . alut pot is not. Syntactic

theory must therefore characterizea level of representaHon that allows us to capture

the noHon of syntactic constituency, permits a characteriza

Hon of the linear order of

elements within and between units, and admits of (at least some) variaHon among

dialects and languages. One form that such representaHons can take is the phrase

structuretree, or phrasemarker.

Phrasemarkersare upside-down treelike structuresin which the nodes are labeled

by syntactic category. For a sentencelike Thedog was humble, the phrasemarker will

have roughly the form shown in figure 6.18. Some of the symbols appearing in the

phrasemarkersthat we will discussare listed in table 6.4.

Although you are no doubt familiar with terms like noun, it may not be so clearwhat

a Noun Phrase( NP) is. Although the subject or object of a sentencesometimesis a

), other sentencescontain subjects

single noun (for example, a proper noun like Seymour

or objects consisHng of a sequenceof words. For example, in figure 6.18 we find the

subjectNP thedog. The sentencewould have been equally grammaHcalwith a subject

as complex as the only otherbookthat I haveeverreadthat I can rememberthe title of, or

everyotherarmadilloin the town. Furthermore, these samesequencesof words can also

appearin object posiHon, for example, after the verb liked in the string I liked. . . We

can categorizeall sequencesof words (phrases) that can appear in subject (or object)

position by assigning them to the category NP, noHng that phrasesthat occupy this

slot contain at least one noun.

246

Chapter 6

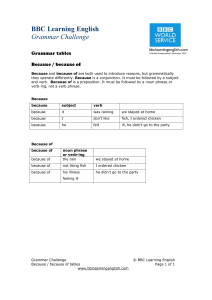

Table 6.4

Symbols used in phrase markers

Symbol

Name

Examples

S

NP

OET

N

TENSE

VP

V

AP

A

Sentence

Noun Phrase

Oetenniner

Noun

Tense Marker

Verb Phrase

Verb

Adjective Phrase

Adjective

A girl walked the dog .

the dog, a girl

the, a, some

dog, girl

PAST, PRESENT

walk the dog

walk, kiss

very smart, tall and thin

interesting

Next we will addressthe TENSEnode. We have madean unintuitive assumptionin

figure 6.18: the tense marker appears in the tree in front of the verb rather than

following it (as we might expect by observing that ordinary past tense verbs like

walkedexhibit a past tense marker, -ed, suffixed after the verb stem). There are some

important reasonsfor this decision, which we will survey later in the discussion. We

should also note that English phrasemarkerscontain only two possible tenses, PAST

and PRESENT. Other languageshave more complex tense systems, but English is

restricted to past and present tense forms of the verb. Referenceto future time is

"

"

accomplishedby means of a helping or auxiliary verb, for example, will , which

precedesthe verb stem. '

In our analysis, the verb s tenseis determinedby selectingeither PAST or PRESENT

as the node under TENSE. Notice that the verb itself is inserted in the phrasemarker

in its basic unaffixed form. By convention, the TENSEnode specifiesthe tense of the

verb immediately to its right , and the tenseof the verb is determinedby the value of

the tensemarker chosenin the tree. The tree for the sentenceThedog is humblediffers

from figure 6.18 only in that the node under TENSEis PRESENTrather than PAST.

The explanation of the need for the Verb Phrase( VP) and Adjective Phrase(AP)

categoriesis parallel to the explanation for the category NP. In eachcasewe find that

although some sentencesexhibit simple adjectivesand verbs, others-contain complex

phrases. For example, instead of the simple adjective humblein figure 6.18, we might

have had the complex AP more humblethan the lowliestsnail, or very, very humble.

Similarly, died, chasedthecat, and gavehis ownera hard time are all VPs that might have

substituted for was humblein the examplephrasemarker.

Two final, brief comments. The Determiner (DET) category comprisesa class of

words including some

, every, and a, in addition to the. These introduce and specify

common nouns. The S node, at the top of the tree, can be thought of in two ways: as

the symbol for Sentence

, and also as the Start symbol that begins eachphrasemarker.

Not every arrangementof nodes into a phrase marker correspondsto an English

sentence. For example, in English the subject NP typically precedesthe VP predicate.

Therefore, reversing the first NP and the VP in figure 6.18 resultsin the ungrammatical

.

string was humblethe dog. A competent speakerof English must know a set of rules

and principles that distinguish possible from impossible phrase markers. Although

some of these restrictions will be particular to a given language, others may follow

from general properties of language. However, it is not always clear at the outset

whether any given syntactic property is to be attributed to a language-specificrule or

: The Representation

of Language 247

Unguistics

a general linguistic principle. Consequently, we will begin by

assuming that every

feature of the language under investigation must be spelled out by a rule, and later

suggestways in which some of theserules might be replacedby generalprinciples.

The rules that describe constituency relations and linear order are called

phrase

structurerules. Here are the rules we need to construct the phrasemarker in

figure 6.18:

(30) S- + NP TENSEVP

NP - + DET N

TENSE- + { PRES,PAST}

VP - + VAP

AP - + A

The rules shown in (30) tell us that asentenceS ) consistsof an NP, a TENSEnode,

and a VP, in that order. This rule encodes the basic order of

English subjects and

predicates. The secondrule specifiesthat an NP dominatesa determinerfollowed by a

noun. The TENSErule provides the two tensealternativesin

English. Exclusivechoices

are listed within braces, set off by commas. The next rule dictates that a VP includesa

Verb followed by an Adjective Phrase, and the final rule indicates that an Adjective

Phrase dominates an Adjective. Although each of these rules

requires considerable

amendmentsto be complete and accurate, this small grammar is sufficient to

generate

the phrasemarker in figure 6.19, which is the sameas that in figure 6.18, without its

lexical items.

In order to associatethe bottom nodes of the tree with actual lexical material

(words), we must apply the processof le.ricalinsertion

. To accomplishthis, we require a

list of vocabulary words called the le.ricon, which specifiesa syntactic

category for each

entry as well as infonnation about its phonological fonn and semanticinterpretation.

In the caseof verbs, a subcategorization

frameis also specifiedto indicate which syntactic

categoriesmay cooccur with eachparticular verb (its complement

structure

). Notice, for

instance, that becan appearwith an NP as well as an AP:

(31) Dogs are [NPa responsibility]NP

(32)

Dogs are [ APquite bothersome]AP

Verbs like perspireand elapsediffer from bein that they cannot cooccurwith NPs at all:

(33)

(34)

A carpenterperspired.

.A

carpenterperspiredsweat.

S

~

"

.

_

.

_

.

.

~

_

.

~

l

NP

TENSE

VP

.

.

"

.

,

.

"

.

,

,

.

.

.

.

"

.DET

I

.

NPAST

V ,AP

I

A

(35)

(36)

The time remaining in Rover' s life elapsed.

" The time remaining in Rover' s life elapsedtwo hours.

Figure6.19

Phrasemarkerfor the sentence

in figure6.18 beforelexicalinsertion

248

6

Chapter

for perspired

for elapsed

, andexceeded

By substitutingexpelled

, we reversethe patternof

in

33

36

.

Each

verb

then, must be associated

(

)

,

(

)

grarnmaticality

judgments

through

with a rangeof appropriatecomplements

. Samplepartiallexicalentriesfor someof the

vocabularyunderconsideration

might look like this:

(37) be, Ibi/ , V, _

{NP, AP}

/

0

, Iprspair, V, _

perspire

0

, lilzps / , V, _

elapse

/

V

NP

_

,

,

,

expel IwpEl

I

exceed

/

V

NP

, Eksid, , _

time, Itaim/ , N

the, lOAf, DET

On thebasisof suchlexicalinformation

, we canselecttheappropriatewordsandinsert

theminto trees.

Transfonnations

In addition to the phrasestructureand lexical componentsof the grammar, collectively

known as the base

, there is a secondtype of syntactic rule that hasplayed an important

role in linguistic theory, the transfonnation

. Unlike phrasestructure rules, this classof

rules does not characterizephrase structure trees. Rather, transformations rearrange

phrase markers in certain ways. The rule discussedabove that optionally moves a

particle to the end of a VP (particle movement) is an example of a transformational

rule.

Another type of phenomenon that has yielded to transformational analysis is socalled

wh-questionfonnation. Wh-questionsare sentencesthat ask 'Who ? Where? Why ?

What?" and so forth , in contrast to yes/ no questions, which merely require an affirmative

or negative answer. Examplesof English wh-questionsare given in (38) and (39):

(38)

Who spilled it?

(39) What is the problem?

Wh-question words in other languagesmay not, of course, begin with the letters

wh- (even in English, how questionsare of the wh-question type), but such questions

typically involve a query correlatedwith somemajor constituent of the sentence

, such

as the subjector object NP. In English the question word takesthe placeof somesuch

constituent and usually appearsat the beginning of the sentence.

In (38), becausewe are questioning the subject, it is not possibleto detect any shift

in position. But in (39), where we are questioning a noun phraseat the end of the VP,

the question word appearsin sentence-initial position. Linguists have analyzed these

types of questions by assuming that the question word is initially generated in a

normal argumentposition(as subjector object), but is consequentlymoved to sentenceinitial position by a transformation. The structure for (39) that is generated by the

phrasestructure rules is shown in figure 6.20.

Notice that we are assumingthat what is a noun, and that it is generatedby the

phrase structure rules for NPs. The transformation of Wh-Movementthen applies to

rearrangethe phrasemarker in figure 6.20, moving what to the front of the S. Another

transformation, Inversion

, will also apply to reversethe order of the verb and subject.

6.21

shows

an

informal

Figure

representationof these two movements.

S

,

Nrr

I

vp

"

"

/

/

"

/

"

I

/the

"

/

DET

N

PRES

V

NP

I problem

I be

I wha

I

S

Unguistics: The Representationof Language

249

NP

~

"

/I "prob

"DET

'the

N

P

I,lPRES

I wha

I

em

be

Figure6.20

Phrasemarkergeneratedby phrasestructurerolesfor the sentence

?

(39), Whatis theproblem

Figure 6.21

Informal representationof transformations applying to the phrase marker in Agure 6.20 in the derivation

of (39), What is the problem?

Perhapsit is not clearwhy we could not simply generatethe word what insentenceinitial position in the initial phrasemarker rather than appealingto a transformationto

move it to the front of the sentence. The reasonis that there is a dependency

between

the fronted question word and its initial argument position that would not be accounted

for by this more direct analysis. The dependencymay be stated as follows:

whenever there is a question word at the front of a sentence

, there is also a corre<

,

sp nding gap a missing constituent inside the sentence. Thus, in (38) there is a

missing subject; in (39), a missing object. Sentencesin which thesepositions are 8lIed,

and a question word occursas well, are ungrammatical:

.

(40) Who Johnspilled it?

.

(41) What is the problem the book?

In the framework we are developing, if we were to directly generatequestionwords

in initial position, we would not be able to correlatesentence-initial wh-words with the

corresponding gaps in argument position. We can, however, explain the facts in the

transformationalaccount. On this analysis, the only way to produce a question word

at the beginning of a sentenceis for that question word to have been moved there

from its normal position, where it was initially placed by the phrase structure rules.

Thus, it is an automatic consequenceof the transformationalmovement that a gap is

left behind.

Chapter 6

250

The

should

fonnation

that question

also predicts

clauses . ( 42 ) and ( 43 ) present some relevant

examples :

in subordinate

In

the

account

transfonnational

( 42 )

I know

( 43 )

John

case

Bill

who

knows

Mary

I know

what

indicates

( 45 )

started

John

, the what

( 46 )

John

knows

object

clause to

insulted

of the lowest

as the subject

Mary

knew

Nancy

~

can move

two

Mary

~

clause :

subordinate

considered

t

Furthennore

in

I

out

knows

word

who was

question

to the & ont of the subordinate

, the

:

t

In ( 43 ), what

.

considered

Nancy

clause . It is moved

Bill

~

knew

.

Wh - Movement

( 42 ), before

of

in the subordinate

position

fonn ( 42 ), as ( 44 ) infonnally

( 44 )

insulted

be possible

I

up , as in ( 46 ) :

clauses

knew

considered

Nancy

t

t

I

Finally , it is possible in both of these cases to move the questioned word all the way

to the front of the main clause. Further rules apply , in this case, to insert a form

of the auxiliary verb do, but (47 ) and (48 ) gives the basic idea of how this works :

(47 )

.

(48 )

do I know Bill insulted

~

t

What does John know

t

I

Nancy considered

Mary knew

t

t

I

The full range of these constructions can be accounted for if we assume that the

Wh - Movement transformation moves a question word to the front of an S. This type

of formulation allows the rule to move the wh -word to either of two positions in

constructions like those above , which contain more than asingleS node .

Question formation , then , involves a movement transformation: the derivation involves

moving a constituent to a new position in the phrase marker . We will now

briefly discuss another type of transformation : a deletion rule .

(49)

Moe added salt, and Curly did too.

Max preferred the mackerel, and Bill the brill .

(51) Herman owned some dogs, and Mary owned some too.

"

"

In each of these sentencesthere is a phrase that is understood but not overtly

present. In (49), for instance, what Curly is understood to have done is to have added

salt. Similarly, Bill is understood to have preferredthe brill, and what Mary owned was

dogs. Thesesentencesare derived by deletion transformationsfrom the structuresthat

:

underlie the following sentences

(50)

(52)

Mae added salt, and Curly added salt too.

(53)

Max preferred the mackerel, and Bill preferred the brill .

(54)

Herman owned some dogs, and Mary owned some dogs too.

: TheRepresentation

of Language 2S1

Unguistics

The rule that converts the tree correspondingto (52) into the one correspondingto

49

( ) deletesa VP, in this caseaddedsalt. There is an interesting specialcondition that

must be met in order for this rule to apply: there must be a copy of a VP that is the

potential deletion target elsewherein the sentence, or the larger discourse. For example

, it would not be possibleto apply the VP-Deletion rule to the structureunderlying

(55) in order to derive (49):

(55)

Moe added salt, and Curly added pepper too.

Another way of putting the point is that this type of deletion transformationcan only

&om the sentencethat

remove material that is redundant, and therefore recoverable

results after the rule applies. In the caseof (49) and (52), this recoverability condition

is met.

The examplesin (50) and (53) involve a rule that deletesverbs, sometimesknown

as Gapping. In the caseof (51) and (54) a rule of IdenticalNoun Deletionis at work. For

both of theserules, the conditions on recoverability of deletion obtain. Notice that the

principle of recoverability of deletion has a very powerful practical motivation it

must be possiblefor a hearerto determineexactly what constituent meaningis missing

. Since the preservation of meaning is what is

in order to interpret elliptical sentences

involved, this may well be a case where general properties of human information

processingare at work , interacting with the form and functioning of linguistic rules.

A CaseStudy

We will now examine more closely a special problem in the syntactic analysis of

English, casemarking, and consider its relevancefor universal grammar. Casemarking

is a device for varying the form of a word , typically to provide an indication of the

role that it plays in a sentence. For example, in (56) the third person pronoun appears

in a different form depending on whether it is the subjector the object of accused

(heis

case):

in the nominativecase, him, in the accusative

'

(56) After John saw Irv leave the victim s room, he accusedhim of the

murder.

In general, English appearsto have relatively little casemarking, especiallyin comparison

to a languagelike Finnish, which has more than a dozen distinct casetypes.

Furthermore, English speakersdraw systematiccasedistinctions only in the pronoun

,

system (and to indicate possessionwith the genitivemarkers ). By contrast, Japanese

which provides case markings for subject and object- ga and 0, respectivelyattachesthem quite generally to subjectsand objects:

(57)

hon-o

Jon-ga

yonda.

John (subj) book (obj) read

'

'

John read the book.

However, although it may appearthat English employs very little casemarking, we

will show that caserelations actually playa highly significant role in English syntax,

a role that may in part be determinedby properties of universal grammar.

We begin this analysis by advancing an abstract hypothesis: all nouns in English

bear case, but it is only in the pronoun system that case is markedby an overt

phonological form. Is such a claim plausible? Are there other circumstancesin English

grammar where a significant morpheme or syntactic category may not have a

S

'

"

'

,

"

~

~

-N

,NP

r

"II TENSE

~

VP

"

!

'

"

I

I

I

,

,

PAST

VI

NPI

I him

I

see

John

252

Chapter 6

Figure6.22

Phrasemarkerenrichedwith indices

phonetic realization? Although most English nouns are pluralized by adding the suffix

/ z/ , there are exceptions such as deer, which are superficially invariant in the singular

and plural. That is, Thedeergrazedpeacefullyis ambiguously about either one deer or

more than one deer. Notice that it will not do to suggest that deeris neither singular

nor plural- that it does not bear plurality - becausein the caseslike (58) in which the

verb inflects for number, deermust be plural sincewereis the third person plural form

of the verb, which can only appearwith plural subjects:

(58)

The deer were grazing peaceably.

The logic of the situation with regard to English case is similar. We know that

pronounsmust be assignedcasebecausethey display it phonetically; we must look for

additional evidence if we wish to claim that other forms (nouns in general) also are

assignedcase- evidencefrom which we can deducethe presenceof caseeven where

it is not overtly marked.

-assignedby

We begin by formalizing the claim that all nouns in English are case

adopting the CaseFilter (from Chomsky 1986):

(59)

CaseFilter

Every NP must bear a case.

According to (59), there can be no grammaticalphrasemarkersin which NPs do not

have a case. Typically , the noun in subject position of any grammaticalsentencewill

receivenominative casemarking, and the object, accusativecasemarking.

. For example, we will treat the

We further hypothesizethat casemarking is assigned

transitive verb as assigning accusativecase to its object. On this view, the verb

"

"

deposits a case property on the object NP, by analogy to the way electrons are

transferred from electron donors to electron recipients in chemical models. We can

indicate this formally by annotating a verb that has assigneda caseand the NP to

which it has assignedit with the sameindex, as in figure 6.22. In this caseseeand its

object are coindexedwith the index i. Sincean NP that is coindexedto a verb hasbeen

assignedthe accusativecaseby that verb, the third person object pronoun appearsin

the accusativecase (him). If the object of seehad been other than a pronoun, case

assignment(and coindexing) would proceed in the samemanner. For example, if Bill

had been the direct object, the phrasemarker in figure 6.23 would result. That is, we

can generalizecaseassignmentso that verbs case-assign their objects regardlessof

whether the assignedcaseshows itself in the form of an overt morphological marking.

Unguistics: The Representationof Language

. -NP

---

I

N

253

S

- - ~~

- -

r

I

PAST

- - -

- - vp

~

//

/

/

" " ' "

VI

NPI

I

N

John

I

Bill

.88

Figure6.23

Indexed

marker

forJohnsawBill

phrase

S

~..- '...' ."'"

'

,

~

,

,

,~~..._~

T

"" ".,.,TENSE

NPI

I

N

I

PAST

/

VI

VP

. /

" " ' "

NP

I

N

John

see

I

Bill

Figure6.24

marker

forJohnsawBill

megalindexed

phrase

In a moment we will turn to evidencein favor of this assumption

, but first we examine

the caseassignmentmechanismwe have introduced a bit more closely.

How does caseassignmentsucceedin linking a transitive verb to its object and

, namely, that a

transferring case? Supposewe start off with the simplest assumption

verb can case-mark any NP. H this were so, we would expect the phrase marker in

figure 6.24, in which seecase-marks the subjectJohn, as an alternative to the one in

figure 6.23. Since caseis not overtly displayed on proper nouns, it might not seem

problematical that the subject in figure 6.24, John, is coindexed with see. However, in

situations where subject position is filled by a pronoun, it is clear that accusativecase

cannot be assignedto subjectposition:

.

(60) Her saw Bill.

(61)

She saw Bill.

We must therefore rule out the possibility of transitive verbs &eely case-assigning

any NP. We can eliminate this option by specifying a domainin which caseassignment

must take place. We will say that caseassigners(in this case, verbs) can assign

case only to NPs that are in their governingdomain. This domain is defined as

follows:

254

Chapter 6

A

a

~_-:I"pf

GOVERNS

Figure6.25

"

of thenotion"governing

domain

Graphic

representation

(62 )

A node (Xis in the governing domain of a node .8 if the first branching

node that dominates .8 also dominates (X(where a branching node is one

that dominates at least two other nodes).

The simplest circumstance that satisfies this definition is illustrated in figure 6.25.

In this case (Xgoverns .8 (and vice versa) because the first branching node that dominates

(x, namely , X, also dominates .8. Below we will see other phrase structure configurations

that fit the definition of government . For now , though , let us formalize the

of

case assignment as follows :

principle

(63 )

CaseAssignment under Government

A case assigner can assign case only to an NP within the governing

domain of the case assigner.

We must now account for how case is assigned to subject position . Recall that the

Case Filter requires every NP to be assigned case. Furthermore , the facts of English (as

evidenced by the form of subject pronouns ) demand that it be nominative case that is

assigned. First , we must identify a case assigner that can assign case to subject NPs.

Our hypothesis is that it is the TENSE node that plays this role , assigning nominative

case to NPs in subject position . Notice that TENSE is an appropriate choice in that

it governs the subject NP , providing some motivation for our earlier decision to place

TENSE before rather than after the verb .

Now consider the phrase marker of the sentence He saw him , incorporating the two

chains of indices that are required by the assumption that the nodes V and TENSE each

separately coindex NPs within their governing domains (see figure 6.26 ). Here TENSE

has case-assigned the subject NP , and V has case-assigned the object NP . Since TENSE

assigns nominative case, the subject receives that case; since V assigns accusative case,

the object is so marked .

We have limited our commentsso far to the details of simple sentencesinformal -

izing the account of English caseassignmentwe want to defend. The sentencesare

. For one thing, they do not involve any Rorid constructions. But

simple in two senses

in a more technical sense they are simple becauseeach contains a single clause

, a

constituent with the basic properties of a sentence. English, as well as other natural

languages, also allows constructionsthat can involve one or more subordinateclauses

in addition to the main clause. Someexamplesof such constructionsare given in (64)

through (68), with the subordinateclausesitalicized:

(64)

The position you aredefendingis preposterous.

(65)

After sizingup thesituation, John died.

S

'

"

'

'N

~

,

,NPJ

"

~

.

1

_

-I~TENS

VP

"

/

I

"

,

PAST

VI

NPI

I

N

hesaw

him

2SS

(

zQ

>

Q

Q

~

(>Q

(~

>

Q

(

~

C

W

:.m

.Q.Q>

Linguistics: The Representationof Language

Figure6.26

Indexedphrasemarkerfor the sentence

HesmDhim

Figure6.27

Phrasemarkerfor the sentence

BrendR

is a spy

(66), 1believe

(66)

I believe Brendais a spy.

(67)

That beansare magicalbecameobvious.

(68)

I suspectthat youfearedthat I knew Vernasneezed

.

Although the syntax of these constructions is complex (and fascinating), we will

restrict our attention to points that bear on the analysisof abstract case, case

assignment

, and government. Severalof theseconsiderationsprovide interesting arguments

in support of this analysisof case. Observe that (69), which is almost synonymouswith

(66), differs somewhatin its syntactic structure:

(69)

I believe Brendato bea spy.

First of all, the verb to beappearsin a tenseless

(or infinitival) form in (69), whereasthe

sameverb occursin (66) in its present tense form, is. The phrasemarkersfor (66) and

S

"

'PRE

/N

-NP

-I"V

,~

1

.ITEN

"NP

/VP

"N

,I~

S

"

'

;

"

,

1

to

VP

"

/

'

"

;

V

NP

~

D

E

N

I

Isp

Ibeli

Bre

be

a

256

Chapter 6

Figure6.28

Phrasemarkerfor the sentence

Brenda

to bea spy

(69), I believe

(69) are roughly as given in Agures 6.27 and 6.28; case indexing is suppressedfor

clarity. Another important detail to notice is that in Agure 6.28 there is no TENSE

marker of the usual sort in the lower S, just the in Anitive marker to. This accountsfor

the fact that be appearsin its untensed uninflectedform. Given our previous assumptions

about caseassignment, we can now account for a very interesting further difference

between the structuresin Agures6.27 and 6.28 that is not immediately apparent.

In the following set of data we have substituted pronouns for Brendawhere it occurs

in the earlier examples:

(70)

I believe she is aspy .

(71)

. 1believe her is

(72)

. 1believe she to be

aspy .

(73)

I believe her to be a spy.

aspy .

Thesedata show that the subjectposition of the tensedsubordinateclauseis assigned

nominative case- just like the subject position in simple sentences

; we see this in

(70). But the subject position of tenselesssubordinate clausesis assignedaccusative

case, as, for example, in (73). We can explain these phenomenain the following way .

We have claimed that it is TENSEthat is responsiblefor assigningnominative caseto

subject NPs. The coindexing operations for the phrasemarker in Agure 6.27 and for

sentence(70) will proceeduneventfully, and nominative casewill be assignedto each

subject position (in both the main and subordinate clauses

); accusativecase will be

to

the

NP

in

the

lower

subordinate

clause

in

object

assigned

Agure6.29 (assumingthat

believedoes not assigncaseinto tensedsubordinateclauses

).

Consider, by contrast, the phrasemarker in Agure6.30, which underliesthe sentence

(73). Sincethere is no TENSEnode in the subordinateclauseto assignnominative case

to the subject of that clause, the theory predicts that nominative casewill not appear

Linguistics: The Representationof Language

S

"" ""- """ "

"

"

""

~

"

~""",,,,"

1

"~",~"",

TENSE

NP1

,

!

pls

/ /

y

"VP

'

/ "" "

"

" 8

""' -..~~""

""""

""

"""""""

""

r

"""""

"",,,

VP

NPJ

TENSEJ

'

//

/

I

/

" " "

PRES V

'

NP

"

/ ' "N

D

Ei

I spy

I

/

- _r

I

believe

S

~""" "- ~'

'

"

~

'

""

"

"",,,'~

T

""""~~""

TENSE

NP1

,

I

N

I

Figure6.30

Phrase

marker

for

I

PRES

/ /

VJ

2S7

she

be

I

.

VP

" "'

" " ,

S-"

""' ~""

'

"

""

"'"""

"

""

"

""",,,,~

1

"""

to

VP

NPJ

'

/

/

""",

Vk

""

""NPk

"

"

""""'

,

"

""

""

"

"

"

DET

N

believe her

be

I

.

the sentence(73), I beliIW her to bea spy, after coindexing

I

spy

258

Chapter 6

in this position. This, of course, leavesus with the question of what does

assigncase

to herin (62). One standardassumptionis that believecan be recruited to

assigncaseto

the subject position of tenselesssubordinate clauses

, perhaps because(unlike in the

caseof (61)) it is the closestpotential caseassignerthat governs the embedded

subject

position. Sincebelieveis a verb, we expect accusativecaseto be assigned, as desired.

Given the constellationof assumptionsthat we have

developed, we can accountfor

what appears, at first blush, to be a very curious correlation between tense and case.

More evidencefor this connection is to be found in contrastslike the

following :

took

.

(74) Mary

him to be a fool.

.

{ cons.ders}

(75)

Mary

made

.

him a believer.

.

{ cons.ders}

(76)

Mary

concluded

that he was a spy.

{ determined}

Concentrating on the caseform of the subject of the subordinate clause, we note

that the contrast between (74) and (76) is expected: subjectsof tenselessclausesare

accusative, and subjectsof tensedclausesare nominative. The

interesting caseis (75).

Here the subordinate clause (if , indeed, it is a clause) apparently contains neither a

tense marker nor the infinitival to. The case form of the third

person pronoun is

accusative(compare: .1 considerhe a spy), patterning with (74) rather than (76), in this

regard.

Again, this is th~ expected result, given our hamework of assumptions. Since the

embeddedmaterial in (75) does not include TENSE, there is no case

assigneravailable

capable of assigning nominative case. Rather, the higher verb must case-assign the

pronoun, resulting in accusativecasemarking.

This pattern can also be observedin sentencescontaining

complementsto the verb

see

:

(77)

John saw her leave.

Here again, the complementto the verb, herleave

, is untensed(compare. Her leavewith

Sheleft). Consequently, caseassignmentof her cannot come Horn within the subordinate

clauseand must be assignedby the higher verb, saw. Notice,

incidentally, that this

account of caseassignmentdirectly explains why strings like .Him/ He a believerand

.Her/ She leave

cannot appear as main clausesin standard English: in both of these

there

would be no availablecaseassigner. This guaranteesthat these

examples

strings

can only appearas complementsto verbs that are capableof

assigningcaseto subordinate

structures(for example, (75) and (77 .

One final pieceof evidencein favor of our theory of abstractcase

assignmentspeaks

more directly to the claim that all NPs are case-assigned(even if

they do not reveal

any overt casemarking). We have claimed that verbs assign accusativecaseto their

direct objects. We might be more speci6c by restricting this

principle to transitive

verbs- verbs that take a direct object. Intransitiveverbs (those that do not

appearwith

direct objects) obviously cannot assignaccusativecase.

then

that

we stipulate

,

,

Suppose

that intransitive verbs do not assign case, as a basic

property of all intransitive

verbs. We can extend this generalization to include passive verbs. That is,

just as

linguistics : The Representationof Language

259

verbphrases

areintransitive

Putanotherway, passive

, suggesting

to assign

case

.

:

thefollowingcontrasts

, let usreconsider

Againstthisbackground

she

(78) a. Johnbelieved Brenda wasaspy.

.

{ her }

.she

b. Johnbelieved Brenda to beaspy.

{ her }

she

(79) a. It wasbelieved Brenda wasa spy.

.

{ her }

she

.

b. It wasbelieved Brenda to beaspy.

{ her }

The pattern in (78) is usual. In (78a) the tense marker in the lower clausewill assign

nominative caseto the lower subject, explaining why Brendaor shecan appearin the

embeddedsubjectposition. Her is ungrammaticalsinceit would require accusativecase

assignment. In contrast, in (78b), in the absenceof a tense marker in the lower clause,

believedassignsaccusativecaseto the embeddedsubject, accountingfor the grammaticality of Brendaand her, but not she. (79a) also follows the expected generalizations.

The caseof the subject of the subordinateclausemust be nominative, as assignedby

the tensemarker in the lower clause. Thus, just as in (78a), either Brendaor she, but not

her, is suitable as the subject in the subordinate clause. Notice that in each of these

three cases

, either the nominative form (she) or the accusativeform (her) is possible, and

. On our analysis, the choice of pronoun shifts

so is the non-case-marked name Brenda

with the choiceof caseassigner(either TENSE, for nominative, or the main clauseverb,

for accusative). The proper name can receive either nominative or accusativecaseand

therefore is generally compatible. However, this generalizationappearsnot to obtain

in (79b).

The puzzle is, Why are noneof the possibilitiesfor the embeddedsubjectgrammatical

in (79b)1 Let us consider each option in turn. First, since the subordinateclauseis

infinitival , there is no tense marker available to assign nominative caseto embedded

subject position, explaining the impossibility of she in subject position. In fact, case

cannot be assignedfrom within the subordinateclause, since there are no governing

caseassignersin the clause. In this regard, the subordinateclausepatterns with (78b).

Of course, in such a circumstance

, it fell to the higher verb believedto assign (accusative

) caseto the lower subject. In (79b), however, the main clausecontains the passive

verb phrase was believed

, which, becauseit is intransitive, is incapable of assigning

accusativecaseto the lower subject. This explains why the third candidate, her (the

accusativeform), is ungrammaticalin (79b).

260

6

Chapter

We have ruled out the nominative form of the pronoun in (79b) becausethere is no

nominative caseassignment, and the accusativeform becausethere is no accusative

caseassignment. But why can't Brenda, the overtly non-case-marked proper name,

appear as the embedded subject of (79b)1 The explanation depends on the crucial

differencebetween casemarkingand caseassignment

to which we are committed. Even

though Brendais not overtly marked for case, it must, on our account, be assigned

either nominative or accusativecase. But in (79b) there is no caseassigneravailableto

assign caseto the subject of the subordinateclause. Consequently, if Brendawere to

appear in this position, it would go without being assignedcase, violating the Case

Filter and rendering the sentenceungrammatical.

Although we have barely scratchedthe surfaceof even one tiny comer of English

syntax, we are already able to glimpse the deductive richnessand explanatory depth

that one hopes for in the scientificinvestigation of a language. Moreover, the study of

aspectsof grammar such as casetheory has come to occupy a prominent position in

current syntactic researchbecauseit has turned out that they figure importantly in our

understanding of the grammars of many disparate languages. The most ambitious

claim we might pursue is that the abstractprinciples that we uncover are universal

that they apply to everynatural language. We turn next to this,

perhaps the most

area

of

research

in

.

important

ongoing

linguistic theory

6.4 Universals

According to much of current linguistic theory, certain linguistic properties (for example

, the CaseFilter and the Maximal Onset Principle; see below) are principles that

are reflected by every natural language. Consequently, although certain

properties

hold for eachindividual language, they are not best understoodas having beencoincidentally

written into the grammar of each language. Instead, linguists, following the

pioneering work of Chomsky (1965) and Ross (1967), have located such principles in

universal grammar (UG). UG is not a grammar in the usual, generative sense of

the term. Rather, UG comprisesthe featuresthat are instantiated in the

grammarsof

all natural languages. Principles of UG are perfectly general, and the rule systems

of individual languages will only need to state the idiosyncratic

properties of the

languagesthey generate.

The principles of UG have also been claimed both to playa central role in the

acquisition of languageby children and to constitute species-specific, domain-specific,

innate properties of mind. The role of the principles of UG in language

acquisition is

discussedin some depth in chapter 9. For now, it will suffice to emphasizethat these

principles are taken to limit the range of hypothesesthat children will normally consider

during the courseof acquisition. Let us examinehow this way of conceptualizing

the processof languageacquisition

proceeds.

.

When a child is faced with the task of deciphering the pattern revealed by some

subsetof sentencesof a language, there will be a number of systemsof rules that are

consistentwith the availabledata (for instance, the sentencesthe child is

exposedto),

although ultimately divergent in the languagesthey generate. The child' s learning

problem can be seenas that of figuring out which of thesepossibilities to reject. The

principles of UG are thought to aid in this task by delimiting the live options- only

those grammarsthat are consistentwith UG will be availableto the child as candidates

for capturing the pattern of the language. Without this restriction on

hypothesis

Linguistics: The Representationof Language

261

fonnation, the child' s task seemsdaunting, and, somelinguists have contended,

impossible

. Researchand debate concerning the role of UG in

languagelearning are at the

center of the ongoing work in linguistics and cognitive science.

The claim that the principlesof UG are speciesspecificturns on the

proposition that

only humanshave languageability . Of course, different speciescertainly have effective

communicationsystems, and some may even possesssystemsthat are

languagelikein

significant regards. Yet most cognitive scientists have come to the conclusion that

whatever suchabilities amount to , they appearto be distinct from the human

capacity

(see, for example, Premack1986). In turn, linguists have reasonedthat although the

principles of UG may well be (part of) what enableshumans to learn language, the

absenceof theseproperties and the learning advantagesthey afford may

explain why

other organismscannot acquirehuman languages.

The principlesof UG have also been assertedto be domain specific- to

govern the

shapesof grammars and thereby direct the course of language acquisition, but to

have no direct impact on other cognitive capacitiesor in other

learning domains. This

position typically forms a part of the modularitythesisthat ascribesdifferent cognitive

abilities to separatefacultiesof mind (seeFodor 1983; Piatelli-Palmerini 1980; Garfield

1987). On this view, sincelanguageis a distinct cognitive

capacity, the principlesof its

theories should not be expected to characterizeother capacities. This entails that the

principles of UG, in particular, are specificto language, and also that the way children

learn languagemay be importantly unrelatedto the way they learn

anything else.

Finally, the principles of UG have been claimed to be innate (see Chomsky 1965,

1980). As such, they are taken to be a part of the organism's

biological endowment,

ultimately to be identified in tenns of human genetics. The argument, roughly put, is

that such principles are not simply inducible from the primary data available to children

- yet learnerscannot fonn

adequatehypothesesabout their own languageswithout

such principles. They must, perforce, be innate. If notions like the CaseFilter are

indeeda part of the biological systemthat guides the fonnation of

grammars, it should

not be surprising to find that abstract case plays a crucial and

widespread role in

English even though there is little overt evidence for casemarking. We should also

find evidencethat thesekinds of principles are at work even in

languagesthat exhibit

no overt manifestationof casewhatsoever. Such results would be

impressiveindeed,

and much of current linguistic researchis directed toward

uncovering this kind of

evidence. Although there are alternative accountsof the relationship between

grammars

and cognition (seeGazdaret al. 1985), and severalrival accountsof the details of

syntactic theory (see Sells 1985; Wasow 1989), much current linguistic researchis

directed at working out the details of casetheory and other subtheoriesof

generative

models of linguistic knowledge.

The task of elucidating the properties of universal grammar would be

relatively

straightforward if all languages uniformly embodied a fixed and unvarying set of

principles. But matters are not so simple. The details of caseassignmentvary from

languageto language. Syllable structure can vary significantly, and there is no single

stresssystem that follows inexorably from principles of metrical structure. Factssuch

as these threaten to vitiate the important claims that have been made about UG.

Indeed, if part of the empiricalappealof UG was that its claimsare testable

againstthe

data of any natural language, the failure to accountfor the data of even one

languageis

deeply problematic.

262

Chapter 6

In an attempt to solve theseproblems, generativelinguists remaincommitted to the

view that the grammarsof particular languagesreflect a set of core propertiescaptured

by the principles of UG, but hold that thesebasicsare subject to a (limited) degree of

variation as well - parameters

that mark the range of possiblehuman languages. Before

we turn to someexamplesof the principles-and-parametersview of things, an analogy

may be useful.

Consider the great variety that seemsto exist in handwoven rugs. On entering a

rug store, we may be struck by the great wealth of different designs: colors, patterns,

and sizesall vary accordingto the country of origin , the maker, and so forth. Yet when

we examine the rugs more closely, it is possible to discern some interesting, though

much less obvious, similarities. Two rugs that appear when viewed from the usual

distance to be constructed from utterly different weaving patterns turn out, when

viewed at close range, to be built up from identical knots- which happen to be

oriented differently and made from wool of different thicknesses

. As thesetwo simple

similar

at

a

,

certain

level

of

examination) take on strikparametersvary highly

rugs (

distinct

. The universal linguistic properties that we have

ingly

superficialappearances

consideredmay well have this character- admitting of small variations on relatively

abstractparametersthat, from afar, createthe appearanceof great diversity .

A Phonological

Example

According' to the theory we have been describing, many of the identifying details of

the world s languagescanbe viewed as small variations on universalthemes. Consider,

again, the matter of syllable structure. At the heart of the syllabiAcationprocessis a set

of fundamental- and invariant- principles. Many phonologists maintain that universal

grammar requiresall languages(as a consequenceof the Maximal Onset Principle,

among others) to have at least some syllablesof the form [CV . . . ], with an onset. No

language is known to violate this principle. Nevertheless, it is subject to parameterization: some languages, like Klamath, a Native American language of Oregon,

require everysyllable to be of this form. Others, like English, pennit someonsetless

syllables. Similarly, all languagesexhibit syllableswith vowels at their nucleus. But the

: some

appearanceof two vowels or of consonantsin nuclearposition is parameterized

exhibit

vowels

or

sonorants

as

,

nuclear

consonants. Others

languages

long

diphthongs,

forbid them and admit only single vowels in the nucleus. Finally, the " coda parameter

"

regulatesthe appearanceof consonantsin syllable-Analposition. No Axedprinciple

determineswhether a languagemust have syllables beginning and ending with con"

"

sonents (closedsyllables

): they are optional, subject to what we may describe as a

"

"

"

"

simple yes/ no parameter. Set to yes, the parameterpermits syllableslike [ . . . VC ];

" "

English is an example. Set to no, the parameterprohibits them, Hawaiian and Italian

" "

being casesin point . But if a languagechoosesthe yes option, a core principle of

universal grammar still requires that it must also allow open syllables without a Anal

consonant. Thus, the range of syllable structuresthat is availableto languagesis quite

broad- but still set within rather stringent limits.

SomeSyntacticPrinciplesand Parameters

The application of the theory of principles and parametersto problems in syntactic

analysis has been one of the most important programs of researchin contemporary

linguistic theory. Following Chomsky (1986), linguists have decomposedsyntactic

theory into a number of subtheories, each one of which contains parameterizedprin-

.

of Language 263

: TheRepresentation

Linguistics

ciples that define its core properties. These subtheoriesinclude casetheory, binding

theory, boundingtheory, theta theory, and X -bar theory. We have already considered

problems in casetheory, which is responsiblefor establishing the principles of case

assignment. The central principle in case theory is the Case Filter the (universal)

principle that requires that NPs must be assignedcase. In fact, the principle may be

more general, for in some languages(for example, Russianand German) it has been

proposed that "certain adjectival phrasesare marked for case. Thus, the principle may

take the form all XPs must receive case," with the value of X being set somewhat

differently for different languages. If this is correct, we would expect languagesall to

involve case, but to assignit and mark it in somewhatdifferent ways.

Binding theory concernsitself with the anaphoricproperties of pronouns, reflexives,

and lexical NPs. These principles capture the structural circumstancesunder which

certain expressions(for example, pronouns) can depend on an antecedentfor their

interpretation. For example, John and he can be naturally construed to be the same

person in (80), but not in (81):

(80)

John thinks [that Scruffy likes him]

(81)

Scruffy thinks [that John likes him]

One part of binding theory constrainsthe interpretation of personalpronounslike him,

as follows:

(82)

Bindingtheory

A pronoun must be free in its local X.

. For

Pronouns that are free are interpreted independently of potential antecedents

that

amounts

to

is

.

What

this

to

clause

out

X

works

,

English personal

roughly

English

pronouns cannot depend for their interpretation on antecedentsthat are locally contained

in the sameclauseas they are. Thus, him can refer to the sameperson asJohnin

80

because

( )

Johnis the subject of the higher clause, whereashim is the object of the

lower clause. In (81) both Johnand him are contained in the sameclause, and so him

must be interpreted as being free from John; that is, him and Johncannot refer to the

sameperson.

Other languagesalso limit the interpretations of pronouns, but in ways that may be

somewhatdifferent from the pattern in English. In particular, languagescandiffer in the

distributions. In

setting for the parameterX in binding theory, producing

' contrasting

Icelandic, for example, the personalpronoun hann ' him appears, at first, to follow the

English pattern in subordinateclauses:

(83)

Jon segir aO [ Maria elskarhann]

Jon says that Maria loves him

The interpretation of (83) is parallel to that of the English translation; JOnand hann

can refer to the sameperson. In tenselesssubordinateclauses

, however, the patterns

diverge:

(84)

Jon skipaOi mer aO [raka hann]

Jon ordered me to shavehim

Whereasin the English translation him can refer to Jon, hanncannot refer to Jon in the

Icelandic sentence. This is becausein Icelandic the value of the parameterX in the

binding theory clausethat applies to pronouns is set differently from the value for

264

Chapter 6

"

'

English. The value for Icelandicis tensedclause: meaning that potential antecedents

must not be membersof the smallesttensedclausecontaining a corresponding

personal

pronoun. In (83) hannis in a separatetensedclausefrom Jon. In (84), however, although

these two terms are in separateclauses

, the smallesttensedclausecontaining Jonalso

contains hann.

Once again we have profit ably compared and contrasted two different

linguistic

systemswithin the principles-and-parametersframework of UG. Similar inquiries have

also been undertaken into the other subdomainsof linguistics. Bounding theory, for

example, concernsitself with how distant a moved elementcan be from its corresponding

gap. In some languagesa moved element must appearwithin the sameclauseas

does the gap, whereas other languages permit greater distance between the two .

is the hypothesizeduniversal principle that establishes theserestrictions on

Sublacency

movement:

(85)

Sublacency

A moved element may not crossX.

where X, as in the previous example, is a parameterthat can be set in a small number

of ways (for example, a clauseboundary or two clauseboundaries), specific to each

language. Seeif you can figure out what the value for X is in the caseof English.

Theta theory is the part of linguistic theory that exploresthe assignmentof thematic

rolesto arguments. Thematic roles determine the action structure of the sentenceby

distinguishing who is doing what, to whom. For example, if we understandJohnas the

agentin (86), then he is taken to be the initiator of the action:

(86)

John rolled down the hill.

It is possible, however, to construeJohnas receiving an action (as a patient), as well,

although this interpretation is easierto assignin (87):

(87)

The rock rolled down the hill.

Theta theory is interested in the principles that mediate the assignmentof these

roles, and like the other subdomainsof the grammar, it contains principles that are

thought to be universal. The central principle of theta theory is the Theta Criterion,

which requires that every argument position must be assignedexactly one thematic

role. In the caseof (86), for example, this principle entails that if John may be a either

the agent or a patient, then he cannot be taken to be both simultaneously, or neither

at all. This criterion and the related theory are currently objects of considerableattention

by linguists who are exploring the application of theseprinciples (along with any

parameterization) acrossthe languagesof the world.

Finally, the subdomainof universal grammar that characterizesthe phrasestructure

of each natural languagecan also be looked at from the perspective of its

principles

and parameters. Earlier we noted that although it is possible to write out a

phrase

structure grammar for each languagethat generatesthe initial phrasemarkersof that

language, there are cross-linguistic generalizations in this aspect of grammar that

suggestan alternative approach. Indeed, sometime ago linguists noticed that there are

regularities in word order and constituent structure both within and acrosslanguages

that deserve to be captured by the principles of UG. X-bar theory, which is the

universal principle at the heart of this component of the grammar, is an

attempt to

distill universal principles of phrase structure and constituency. To the extent that

Linguistics: The Representationof language

265

X-bar theory succeeds

, the phrase structure rules for each languagecan be simplified

and will only need to record the featuresof phrasemarkersthat are idiosyncratic in a

particular language. Proposedprinciplesinclude the claim that in all languagesa phrase

of the form XP must contain an occurrenceof X , which is called the headof the phrase.

That is, NPs must contain nouns asheads, VPs must contain verbs asheads, and so on.

The ordering of subconstituentswithin a constituent is one locus of variation across

languages. In some languagesadjectives follow the noun (for example, Hebrew), in

somethey precedeit (for example, English), and in someboth alternativesare possible

(for example, French). Nevertheless, there are certain subregularities that generally

obtain. For example, languages like Japanese

, which is verb-final, also tend to be

postpositional (objects of prepositions follow prepositions), contain relative clauses

that precedethe noun they modify , and have adjectivesthat precedethe noun. These

- the

are languagesin which the HeadParameter

parameterthat establishes in which

or

of

a

constituent

its

(left

)

periphery

right

phase head will be located- is set to the

"

"

value heads right . In Hebrew, in contrast, where the verb is VP-initial, there are

prepositional phrases, relative clausesfollow the nouns they modify , and adjectives

follow the noun, the setting is "heads left." Although languagessometimestolerate

some exceptions to these ordering generalizations(for example, English- try to set

the Head Parameterand note any exceptions!), the Head Parametergenerally makes

accuratepredictions about connectedaspectsof word order acrosslanguages. In this

regard, it is an important component of the theory of Universal Grammar.

to the Theory

Challenges

's

Chomsky system of UG has been extremely influential in guiding the development

of researchprojects in many areasof cognitive science. Yet, like any important idea,

the position we have sketchedhas been seriously criticized, &equently amended, and

in somecasesjettisoned in favor of alternative &ameworks. We closeour discussionof

UG by briefly noting someof the interesting areasof continuing researchon UG, with

special attention to the more general psychological and biological claims that have

been made for UG.

The hypothesized innate universal grammar is often compared ( by Chomsky and

"

"

others) to a bodily organ- albeit a mental organ - that is organized in brain and

other neural tissue. Although the details of the biological basisof the linguistic capacity

are by no means well understood (see chapter 7), it is often claimed that UG

representsa modular, highly specializedcapacity and it is sometimessuggestedthat

it has a specializedgenetic basis. That is, the notion of linguistic innatenesshas been

taken to meanthat there must have been highly specificnatural selectionin the course

of human evolution for the details of UG. This view is sometimesfurther popularized

to suggest that there are specific genes for language. But there is little evidence to

support this notion. In fact, few organ systemsor behaviors are the products of single

genes. There is certainly little basisin contemporary molecularbiology to support the

notion that specific informational states, like the CaseFilter or abstract principles of