Rural Industry Transition in China: Local State to Land Revenue

advertisement

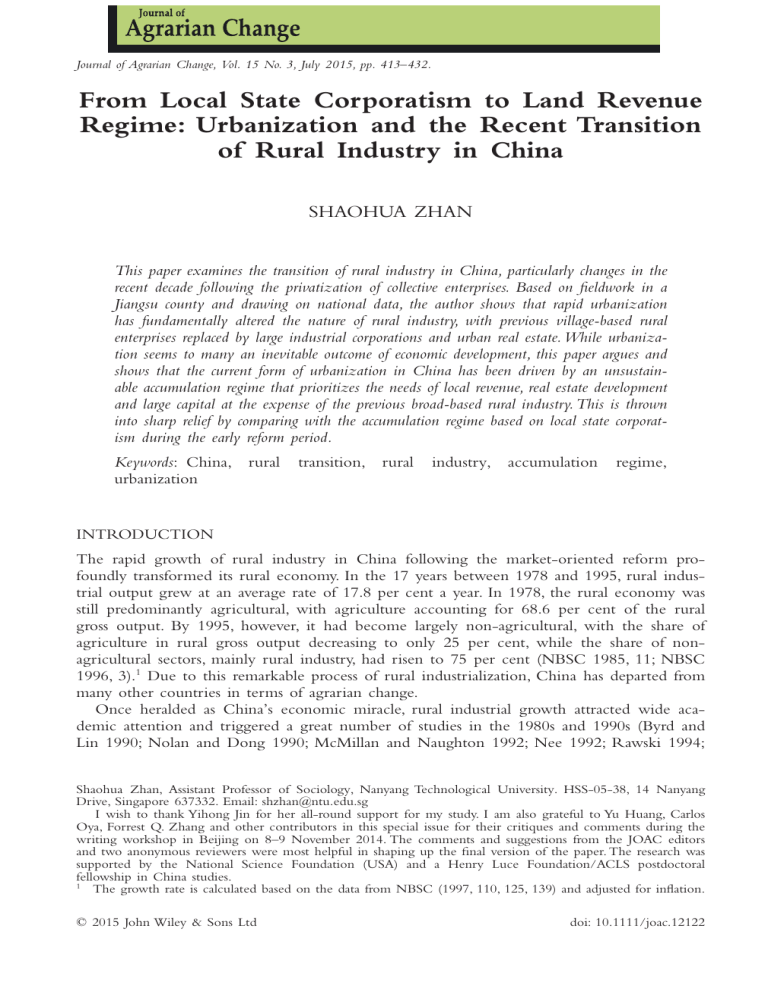

bs_bs_banner Journal of Agrarian Change, Vol. 15 No. 3, July 2015, pp. 413–432. From Local State Corporatism to Land Revenue Regime: Urbanization and the Recent Transition of Rural Industry in China SHAOHUA ZHAN This paper examines the transition of rural industry in China, particularly changes in the recent decade following the privatization of collective enterprises. Based on fieldwork in a Jiangsu county and drawing on national data, the author shows that rapid urbanization has fundamentally altered the nature of rural industry, with previous village-based rural enterprises replaced by large industrial corporations and urban real estate. While urbanization seems to many an inevitable outcome of economic development, this paper argues and shows that the current form of urbanization in China has been driven by an unsustainable accumulation regime that prioritizes the needs of local revenue, real estate development and large capital at the expense of the previous broad-based rural industry. This is thrown into sharp relief by comparing with the accumulation regime based on local state corporatism during the early reform period. Keywords: China, rural urbanization transition, rural industry, accumulation regime, INTRODUCTION The rapid growth of rural industry in China following the market-oriented reform profoundly transformed its rural economy. In the 17 years between 1978 and 1995, rural industrial output grew at an average rate of 17.8 per cent a year. In 1978, the rural economy was still predominantly agricultural, with agriculture accounting for 68.6 per cent of the rural gross output. By 1995, however, it had become largely non-agricultural, with the share of agriculture in rural gross output decreasing to only 25 per cent, while the share of nonagricultural sectors, mainly rural industry, had risen to 75 per cent (NBSC 1985, 11; NBSC 1996, 3).1 Due to this remarkable process of rural industrialization, China has departed from many other countries in terms of agrarian change. Once heralded as China’s economic miracle, rural industrial growth attracted wide academic attention and triggered a great number of studies in the 1980s and 1990s (Byrd and Lin 1990; Nolan and Dong 1990; McMillan and Naughton 1992; Nee 1992; Rawski 1994; Shaohua Zhan, Assistant Professor of Sociology, Nanyang Technological University. HSS-05-38, 14 Nanyang Drive, Singapore 637332. Email: shzhan@ntu.edu.sg I wish to thank Yihong Jin for her all-round support for my study. I am also grateful to Yu Huang, Carlos Oya, Forrest Q. Zhang and other contributors in this special issue for their critiques and comments during the writing workshop in Beijing on 8–9 November 2014. The comments and suggestions from the JOAC editors and two anonymous reviewers were most helpful in shaping up the final version of the paper. The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (USA) and a Henry Luce Foundation/ACLS postdoctoral fellowship in China studies. 1 The growth rate is calculated based on the data from NBSC (1997, 110, 125, 139) and adjusted for inflation. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd doi: 10.1111/joac.12122 414 Shaohua Zhan Lin 1995; Whiting 1996; Oi 1999; Qian 2000). After rural collective enterprises – also known as Township and Village Enterprises (TVEs) – were privatized in the early 2000s, however, academic interest quickly dissipated and changes in rural industry fell below the radar of most academics. Studies in the 1980s and 19990s offered many insightful interpretations. One example was Jean C. Oi’s notion of local state corporatism, which highlighted the important role of local government in the development of rural industry. According to Oi, fiscal reforms in the late 1970s and early 1980s allowed local governments to retain the residual revenue after fulfilling the tax quota paid to the central government. As a result, the more surplus rural collective enterprises generated, the more of such residual revenue would flow to local coffers. Thus local governments developed a considerable incentive to promote rural industry (Oi 1999, 18–53). Oi’s argument is subject to debate. For example, the state-centric explanation might have not paid enough attention to the role of rural entrepreneurs (Nee 1992; Whiting 1996; Huang 2008; Nee and Opper 2012). In addition, at least some credit should be given to the Mao era (1949–76) when rural industrial growth had already started taking shape (Wong 1988; Putterman 1993; Bramall 2007). Nevertheless, the thesis of local state corporatism brought to light the role of local government as a rational actor pursuing revenue while being relatively independent of the central government. It also highlighted the necessity to see local revenue generation as an important factor in China’s rural transitions. Local state corporatism arose from a specific historical context in which the rural reform introduced a market economy but still allowed local authorities – townships and villages – to retain control of collective assets, including collective enterprises established in the Mao era. After the mid-1990s, however, local state corporatism declined as collective rural enterprises lost the momentum of rapid growth, and local governments tried to free themselves from the liability of loss-making collective enterprises. Nevertheless, the incentive of local government to pursue revenue has not gone away with the decline of local state corporatism. In the past decade or so, a new method to generate revenue has taken hold and been widely practiced across the country; that is, local governments taking in revenue by expropriating rural land and selling it to developers or very large corporations. This method of revenue generation is called land revenue (tudi caizheng in Chinese). It has been reported that local governments raked in 4.1 trillion yuan from land sales in 2013, accounting for 60.2 per cent of total local revenue (Zhang 2014). National statistics show that land sales made up about 50 per cent of local revenue in the 10 years between 2004 and 2013.2 Deriving revenue from rural land is an important factor behind ongoing massive urban expansion in China, and has exerted profound impacts on the rural economy and society. Like local state corporatism, expropriating land for revenue has contributed positively to economic development, since it has allowed local governments to increase infrastructure investment and provide funds to promote strategically important industries. However, it has also deprived millions of rural residents of access to land and become the most reported cause of rural unrest (Sargeson 2013; Zhang 2015). However, few studies have been conducted to examine the impacts of land revenue on rural industry. This is puzzling, given that the generation of local revenue was regarded as one of the most important factors behind rural industrial development in the early reform period. 2 Data sources: the China Land and Resources Statistical Yearbook for 2012 (p. 6), the China Land and Resources Statistical Bulletins for 2012 and 2013, and the China Statistical Yearbook for 2013 (ch. 9-1). © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Urbanization and the Transition of Rural Industry in China 415 This study seeks to fill this gap by examining how ongoing urbanization based on land revenue has affected rural industry in China. I will compare the current accumulation regime, what I call the land revenue regime, with the one based on local state corporatism in the 1980s and 1990s. By accumulation regime, I refer to a dominant mode of surplus generation that is often led by local government and serves to increase local revenue, but nonetheless involves and benefits other actors such as rural residents and private investors. At the centre of my analysis is the question of how an accumulation regime defines and affects small rural producers’ livelihood and property rights (broadly defined), which are important themes in studies of rural transitions (Bernstein 2010, 8–9). My research is based on a case study of W county in Changzhou Prefecture of Jiangsu Province,3 a place that was renowned for rural industry in the 1980s and 1990s. I also draw on national data, media reports and secondary sources to locate the case in the national context. A major finding is that the impact of the land revenue regime on rural industry has been almost the opposite of that of local state corporatism. While local state corporatism promoted rural industry by supporting and involving most rural residents in industrial production, the land revenue regime forced almost all village-based rural enterprises to close and replaced them with a small number of very large corporations, which were concentrated in industrial parks. As a result, rural residents lost their enterprises and jobs while at the same time they were excluded from large industrial corporations and profitable urban sectors. Why did the two accumulation regimes, both serving to generate local revenue, differ so greatly in their impacts on rural industry? The answer lies in how an accumulation regime regulates the property rights and livelihoods of rural residents. Under the regime of local state corporatism, rural residents were entitled to access land and means of livelihood based on village resources. When a local government took village resources such as land, water and raw materials for the development of rural industry, it had to involve the rural residents because the latter’s rights and livelihoods were attached to those resources. Under the land revenue regime, however, the rights and livelihoods of rural residents are separated from village resources. After village land was expropriated, for example, the land became the property of local government, and the rural residents were no longer entitled to profits or employment opportunities generated from village resources. The separation of rural residents from village resources has undergone two phases: the first was the privatization of collective enterprises in the late 1990s and early 2000s; and the second, sequential phase is the ongoing process of land urbanization. By comparing the two accumulation regimes, this paper extends the literatures on both local state corporatism and land urbanization. It shows that the incentive of local government to increase revenue can produce divergent outcomes: while it promoted broad-based rural industry in the early reform period, when the rights and livelihoods of rural residents were tied to village resources, it has undermined it during recent land urbanization, as such institutional connections have been severed. It is argued here that the incentive alone cannot explain the rise and fall of Chinese rural industry over the past three decades. One must take into account how rural residents were incorporated or excluded from the process of revenue generation. In addition, the difference between local state corporatism and the land revenue regime reveals that ongoing urbanization is an exclusionary process that prioritizes the needs of government revenue, real estate developers and large corporations while undermining rural residents’ rights and livelihoods in the long run. Finally, the evidence suggests that the 3 The names of places below prefecture level are anonymized for the privacy and protection of local informants, and so are the names of interviewees. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 416 Shaohua Zhan contemporary land revenue regime is not a sustainable alternative to local state corporatism, abandoned in the late 1990s, as the former’s capacity for generating surplus either for revenue or profit has started to decrease in recent years. The next section introduces research methods and data collection. After that, I discuss the accumulation regime based on local state corporatism in W county, and the subsequent abandonment of the regime and the first separation of rural residents from village resources; that is, the privatization of collective enterprises. I then proceed to discuss the land revenue regime and urbanization, and show how the further separation of rural residents from the land has led to the decline of village-based industry. The final section reveals how the land revenue regime is unsustainable both socially and economically. RESEARCH METHODS AND DATA COLLECTION The data used in this paper mainly come from a case study of W county in Changzhou Prefecture of Jiangsu Province. In addition to data collected from the county, I consulted national statistical data, policy documents, media reports and secondary sources to show how the experiences of W county were different from or similar to general trends in rural industry. W county is located in Changzhou Prefecture, southern Jiangsu Province, where the development of rural industry was called the ‘Sunan model’ and characterized by the prevalence of collective enterprises in the 1980s and 1990s (Figure 1). The Sunan model represented the general situation of Chinese rural industry in the early reform period, in which collective enterprises were the major organizational form of production. In contrast, another two famous models, the Wenzhou model, which was characterized by private enterprises, and the Pearl River Delta model, which refers to the wedding of rural enterprises in Guangdong Province with foreign capital from Hong Kong as early as the 1980s, did not represent the national situation (Naughton 1995, 156–7). It should be noted that the highly developed nature of rural industry in southern Jiangsu owed much to its geographical and social proximity to Shanghai and Nanjing, two of the most important urban industrial centres in China. This situation could not be generalized to the rest of the country. My first fieldwork in W county took place between August 2010 and January 2011, during which time I made three field trips to the county, each lasting about a month. I collected local statistical data and policy documents, and interviewed officials at both county and township levels. To further understand changes in rural industry, I selected Z village in the county for village-level investigation. The population of Z village was about 1,500 in the early 1980s and has remained at about this number for the past three decades. However, from the mid-1990s onwards, Z village started to see migrant workers arrive and the migratory population reached about 3,000 in the village, twice that of the local population. Rural industry started very early in the village. Its first factory was established in 1963, to make aluminium labels on machines. After that, the village tried to establish several factories: some succeeded and some failed. In 1981, when Z village adopted the Household Responsibility System, it was running three factories making shoe accessories, machine labels and textiles. Z village established another three collective enterprises in the 1980s. The shoe accessory factory and an electric motor factory were the most successful, and both of them remained profitable throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Half of the labour force of the village (almost 500) was employed in collective enterprises including TVEs in the early 1980s, attesting to the high level of TVE development in the area. The rural residents were still engaged in farming in the 1980s and 1990s, but the role of farming was only subsidiary and its main function was to provide food for local rural © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Urbanization and the Transition of Rural Industry in China 417 Figure 1 The approximate location of W county households. Private enterprises in the village emerged in the 1980s and grew thereafter. By the time of my fieldwork, there were 135 private enterprises in the village. However, as we shall see, the expropriation of the village land that started in 2010 would shut down almost all of the enterprises. I interviewed all four incumbent village officials and selected about 50 households for in-depth interview. Among the households I selected, about 20 households were running their own private enterprise at the time of interview, and another 10 households had owned an enterprise previously. For the rest that did not run a private enterprise, most had worked in collective enterprises. In addition, I also performed on-site observation of factory production, social activities and everyday life in the village. In August 2014, I revisited W county and Z village, and conducted follow-up interviews with village officials and five households. I also visited six government agencies and four large enterprises to collect information on local governments’ urbanization and industrial policies. LOCAL STATE CORPORATISM IN W COUNTY Jean C. Oi (1992, 1999) coined the concept of ‘local state corporatism’ in Chinese rural industry and used it to illuminate the control and management of rural industry by local © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 418 Shaohua Zhan Table 1. Industrial enterprises and workers in W county, 1985 Number Number of workers (thousands) Percentage of workers employed Total County enterprises Township enterprises Village enterprises Household enterprises/ private enterprises 3,564 298.8 100 178 40.2 13.5 1,360 116.5 39.0 2,026 115.6 38.7 No data 26.5 8.9 Source: the W County Gazetteer for 1988. government. Many other scholars have subsequently employed the concept in their own research (Peng 2002; Edin 2003; Wen 2011). However, these studies have concentrated more on the role of local government than on those rural institutions that conditioned government actions and policies, such as collective landownership (Pei 2002). This section will emphasize, based on the case of W county, that rural industrialization, though led and managed by local governments and serving to increase local revenue, also involved and benefited rural residents in the 1980s and 1990s under the rural institutions. This can be seen from how collective rural enterprises recruited workers as well as from how rural households set up private enterprises. According to W county’s 1988 gazetteer, there were approximately 3,564 industrial enterprises (excluding private household enterprises) in 1985, of which 3,386 – that is, 95 per cent of the total – were collective TVEs. In addition, 299,000 labourers worked in industrial enterprises in 1985, accounting for 37.8 per cent of the total labour force. Most industrial labourers, 77.7 per cent of the total, were working for collective TVEs. A small number of households had set up private enterprises, which employed about 8.9 per cent of industrial labourers (Table 1). These data thus showed that rural accumulation in W county was predominantly based on collective enterprises. Collective enterprises provided a way for local governments and village authorities to control and manage collective resources: they appointed TVE managers, supervised enterprise production, provided financial support and even went as far as to market TVE products (Naughton 1995; Walder 1995; Oi 1999). However, rural residents were also involved, and in many cases it was they who created the enterprises. In the 1980s and early 1990s, collective enterprises mainly employed rural labourers within the county, with residency-based hiring practices; that is, a township enterprise employed rural labourers from the township, and a village enterprise hired people within the village. This was so because rural residents had the right of access to village resources. When a collective enterprise took these resources – for example, a plot of land – it had to hire the rural labourers who were living off the resources. In other words, the distribution of jobs in collective enterprises was a reflection of the rights of rural residents to village resources. This form of institutional connection was the most pronounced in the case of village enterprises, because both the collective enterprises and the village resources were within the boundary of the village. By the late 1980s, Z village had established six collective enterprises, and all these enterprises were built with village resources such as land and collective funds and employed rural labourers within the village. Thus, villagers regarded these enterprises as their common property, cared about their development and even became emotionally attached. When I interviewed some of the workers in 2010, a decade after the enterprises © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Urbanization and the Transition of Rural Industry in China 419 were privatized, they still loved to share with me how they together created and contributed to these enterprises.4 In the case of township enterprises, the recognition of the entitlements of rural residents to village resources was indirect but nonetheless detectable. In the 1980s and early 1990s, township governments in W county often pooled village resources to establish collective enterprises. In exchange, the township enterprises had to offer jobs to rural labourers from the villages. According to my interviews in Z village, a township government often gave a quota of jobs to each village based on the contributions of the villages; and the villages would decide who should get the jobs.5 In addition, a township enterprise had to offer jobs to the households if that township enterprise took their lands. Collective enterprises brought enormous benefits to local rural residents because TVE jobs were much more remunerative than farming. In Z village, a worker in a collective enterprise could earn 500–1,000 yuan a year in the mid-1980s, whereas a person who farmed could make only 100 yuan at most. The accumulation regime based on local state corporatism also benefited rural households that ran private enterprises. A small but increasing number of households started small factories in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Z village’s archives recorded 23 private household enterprises in 1991. These households usually had members who worked for collective enterprises as technicians or salespeople, and thus obtained the technical know-how or marketing skills necessary to run an enterprise. Another important reason why rural households were able to establish private enterprises was their access to village resources. In the 1980s and early 1990s, many rural households used their own houses as factories. State policy regulated that every rural household was entitled to a plot of housing land (zhaijidi in Chinese). With the expansion of household business in the late 1980s and 1990s, the demand for housing land surged. To obtain more land, rural residents split a household into two or more so that they could apply for land to build extra houses. While the population of Z village remained at around 1,500 people, the number of households jumped from 420 in 1988 to 596 in 1992.6 Another kind of land that rural households could use for private enterprises was the small private plots owned by every household. This land, which was called ziliudi – literally, self-kept land – was given to rural households in the early 1960s after the failure of the Great Leap Forward. However, these plots were very small. In Z village, they amounted to less than 0.1 mu per person. Thus only a few households in Z village managed to build a factory on this kind of land. In summary, the accumulation regime based on local state corporatism involved and benefited the majority of the rural residents under rural institutions that protected their entitlements to village resources. By the mid-1990s, however, local state corporatism had started to decline, leading to the first separation of rural residents from village resources; that is, the privatization of collective enterprises. PRIVATIZATION AND THE FIRST SEPARATION OF VILLAGERS FROM VILLAGE RESOURCES In the 1990s, local state corporatism based on collective enterprises ran into a crisis. Change first came from the top. Following Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour in 1992, the Chinese 4 Interview no. 8, 5 September 2010; interview no. 14, 8 September 2010; and interview no. 17, 10 September 2010. 5 Interview no. 14, 8 September 2010. 6 Data source: the Z village archives. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 420 Shaohua Zhan Communist Party announced in November 1993 that it would establish a pure market economy and reform public ownership, including both State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and collective TVEs.7 The emergence of new forces at the local level also worked against collective TVEs. This section will discuss how changes at both central and local levels undermined local state corporatism and led to the privatization of collective enterprises. The Declining Capacity of Collective TVEs Deng’s 1992 southern tour gave a boost to TVEs. With the influx of foreign capital, the ballooning of exports and a new wave of investment frenzy, TVEs grew rapidly in the first half of the 1990s, particularly in coastal areas such as southern Jiangsu. The national gross output of TVEs more than tripled, jumping from 1.18 trillion yuan in 1991 to 3.83 trillion yuan in 1995.8 This rapid growth sustained the accumulation regime of local state corporatism well into the mid-1990s. However, behind the facade of the growth was the declining capacity of TVEs to generate sufficient surplus to sustain the regime. In 1994, TVEs in W county experienced robust growth, with gross output increasing by 36 per cent, according to the county’s annual industrial report. However, the report also showed that the number of loss-making collective enterprises had reached 964, accounting for 18.1 per cent of all collective enterprises. The increasing number of loss-making enterprises worried local governments and village authorities, because these enterprises started to become a liability rather than a source of revenue (see also Oi 1999). Mr Pan, aged 56 at the time of interview, had been the Party secretary of Z village for more than 20 years. He explained to me why the village authority wanted to privatize loss-making collective enterprises: ‘From our standpoint, we should sell loss-making enterprises if possible, and close them down if no one wants to take them. Otherwise benefits go to managers but debts would be left to the village [which collectively owned the enterprises].’9 His words reflected the general situation at the time. If the government did not get rid of these enterprises, it would have to keep pouring resources into them to keep them alive. The declining capacity of TVEs was closely linked to the expansion of private enterprises dating back to the 1980s. By the 1990s, private enterprises in southern Jiangsu had emerged as an important force in the rural economy. According to the statistics of the township where Z village is located, private enterprises in 1998 accounted for half of the industrial output and two thirds of the market share of services, including but not limited to retail trade, transportation, hotels and restaurants. The expansion of private enterprises not only heightened the competitive pressure on collective enterprises but also drained the latter’s resources. More importantly, it led two key sets of actors to abandon collective enterprises. One was talented employees in collective enterprises, including technicians and sales personnel, who wanted to establish private enterprises of their own. The other was TVE managers, who felt that their rewards in the collective system were unacceptable, as the owners of private enterprises were making much more money than they did. 7 Deng, apparently backed by the military, made a series of speeches during the tour and urged for the reform and opening up to be pushed further. The conference refers to the Third Plenary Session of the 14th Central Committee. 8 The calculation is based on data from MOAC (2003, 9), adjusted for inflation. 9 Interview no. 21, 12 September 2010. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Urbanization and the Transition of Rural Industry in China 421 The Exodus of Talented TVE Workers and the Rise of Management Interest In the 1980s, TVE workers who ran private enterprises usually did not resign from collective enterprises because their private enterprises were small and vulnerable. By the 1990s, however, these workers, who were usually talented technicians and sales people, were ready to leave the collective enterprises. In Z village, the number of private household enterprises increased from 23 in 1991 to 65 in 1999. Countywide, the number of private industrial enterprises, mostly household enterprises, increased to 9,614 in 1998, producing 56.4 per cent of the gross output and absorbing 73.2 per cent of industrial labourers.10 It had become a trend in the 1990s for TVE workers, particularly those with knowledge and skills, to resign and start private enterprises of their own. Their leaving not only drained the resources of collective enterprises but also heightened competitive pressure on them, since worker-started private enterprises usually followed collective enterprises and produced the same products. The success of private enterprises also affected another key actor: the TVE manager. TVE managers played a very important role in local state corporatism during the 1980s. By the 1990s, however, more and more of them had started to pursue personal interests in ways that undermined the collective system. The reason was that profits from private enterprises had become more attractive than salaries in collective enterprises. It was not rare for a successful private enterprise to make tens of thousands of yuan a year in the 1990s, which could be several times a TVE manager’s annual salary. Attracted by the allure of private profits, many managers started their own enterprises with the resources of collective enterprises, such as money, raw materials and trade networks. This was, of course, against the law. A common strategy was to set up a private enterprise in the name of their families, relatives or friends, and divert collective resources to the private enterprise. A document released by W county government in 1993 revealed that this problem had become increasingly serious. The First Separation of Villagers from Village Resources With both central and local forces at work, local governments started to privatize collective enterprises in the late 1990s. In 1997, the central government issued a document demanding the change of collective TVEs to joint-stock companies.11 After only 2 years, many provincial governments started to push for full privatization (Zhang and Yuan 2003, 241–3). Jiangsu Province, which was renowned for collective enterprises, was particularly active in privatization, with statistics showing that privatization advanced faster in that province than in the rest of the country (Figure 2). The method of privatization was the management buyout (MBO). The government sold collective enterprises to incumbent managers at evaluated prices that were often much lower than the market prices. Afterwards, the collective enterprises became private, under the absolute control of former managers. The government compensated the workers with a proportion of the money from the sale of the enterprises, and the workers lost all entitlements to the enterprises. To workers in collective enterprises, particularly those whose enterprises were still running well, privatization was an arbitrary process to separate them from village resources. As noted in the previous section, for rural residents, collective enterprises were an extension of village 10 11 Source: the W County Statistical Gazetteer for 2001. The serial number of the document was Zhong Fa (1997) No. 8, which was released on 11 March 1997. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 422 Shaohua Zhan Figure 2 The number of collective TVEs in China and Jiangsu, 1997–2004 Source: the China TVE Yearbooks for 1998–2005. resources, to which they had the right of access. By privatizing collective enterprises, the government deprived TVE workers of this entitlement. As a result, they lost lifelong employment and shares in enterprise assets, and only received a modicum of compensation. The majority of rural residents, particularly those who had worked in collective enterprises, were angry about the mandatory privatization. Ten years after the privatization, former TVE workers I interviewed still complained about the arbitrariness of the process. In their opinion, collective enterprises were built with village resources through collective efforts. Thus every worker should have a share in the enterprises and a say in privatization. The use of MBOs did not reflect this reality. The privatization, on a massive scale, of the rural collective enterprises in China has attracted the attention of some Marxist scholars. For example, David Harvey (2003, 153–4) depicted the privatization of the TVEs as a part of the global process of accumulation by dispossession, along with the spread of neo-liberalism. More recently, Michael Webber (2008) included the privatization of TVEs in a long process of primitive accumulation in China that started at the onset of the rural reform. As noted previously, this privatization process was not simply a top-down or outside-in process that aimed to dispossess TVE workers. Rather, it was derived from a multiplicity of forces: local governments wanted to get rid of loss-making collective enterprises; talented TVE workers exited and set up private enterprises; and the managers of collective enterprises were drawn to private profits. As a result, a number of key actors, including local governments and village authorities, TVE managers and talented TVE workers, all turned away from local state corporatism in the 1990s. More importantly, the separation of villagers from village resources was only partial, because rural residents still had access to land, housing and jobs within the village. This allowed former workers of collective enterprises either to establish small private enterprises of their own or to find jobs in those private enterprises. In other words, continued access to © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Urbanization and the Transition of Rural Industry in China 423 village resources incorporated rural residents into an accumulation regime based on household enterprises, which started to emerge as early as the 1980s. According to official statistics, the number of rural private industrial enterprises in Changzhou Prefecture, where W county is located, increased from 10,563 in 1999 to 17,359 in 2005.12 However, according to my fieldwork, many household enterprises were too small to be included in the official statistics. Thus the actual increase in rural private enterprises in this period must be larger than reported. In Z village, the number of private enterprises increased rapidly, from 65 in 1999 to 134 in 2003, and further to 177 in 2006, before it decreased. Not all rural households could establish factories because that required a large amount of investment.13 Approximately 140 out of 400 households in Z village owned factories in 2006, and they were considered the better-off households. For those that did not own factories, job opportunities were ample due to the flourishing of small private enterprises. And as natives, they could find well-paid jobs and work as managers, accountants and technicians, whereas manufacturing work was now carried out by migrant workers. While privatization extricated local governments from the liability of loss-making collective enterprises, it also motivated them to seek new sources of revenue. In the past 10 years, as with many other local governments in China, the W county government has found a new source of revenue: rural land. The next section will show how the land revenue regime has driven the process of urbanization in W county, and how this new method of revenue generation has fundamentally changed the nature of rural industry by separating villagers from village resources. URBANIZATION AND THE LAND REVENUE REGIME The early 2000s was a golden age for small, village-based rural enterprises in southern Jiangsu: while collective enterprises were privatized, rural residents still had access to village resources such as land; a great amount of farmland was turned into factories; and migrant workers from hinterland regions swarmed in, providing rural enterprises with abundant cheap labour. However, the golden age did not last long. In the mid-2000s, many small rural enterprises had to close down due to the emergence of the land revenue regime. This section will focus on how local governments played a leading role in this transition, and it will show how land urbanization forced out village-based rural industry by separating villagers from village resources. The Rise of Land Revenue The expansion of small private enterprises and the increase in taxes collected from these enterprises provided a new source of revenue, but it did not seem to be enough to satisfy the demand. This was probably because small enterprises, though large in number, could not generate as much tax income as local governments desired, and the administrative cost of collecting taxes from such a large number of enterprises was high, with some of them not even officially registered. In addition, the 1994 tax reform, which gave the central government 12 Data source: the Changzhou Statistical Yearbooks for 2000 and 2006. I estimate, based on my interviews, that a household must spend at least 300,000 yuan to open a small textile factory. 13 © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 424 Shaohua Zhan Figure 3 Real estate investment and sales in Changzhou, 2000–12 30 25 billion yuan 20 15 10 5 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 investment 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 sales Source: the Changzhou Statistical Yearbooks for 2001–13. the lion’s share of tax income (60–70%), undercut the amount of tax revenue for local coffers (Shao 2010). These factors motivated local governments to seek new sources of revenue. In addition to the need for revenue, the emergence of the land revenue regime was also made possible by a combination of the following factors. The 1998 housing reform established an urban housing market and provided a precondition for the real estate boom in the 2000s. In addition, the expansion of private enterprises in southern Jiangsu during the 1990s increased the demand for land to build factories, giving rise to a market for land transactions. In the 1980s, rural households used their own houses as factories. But they started to rent or purchase land from local governments and village authorities in the 1990s. This turned rural land into a source of revenue for local governments and village authorities, paving the way for local governments to sell land to developers at much higher prices in the 2000s. Another factor was that rural industrialization in the region, based on local state corporatism in the 1980s and 1990s, accumulated a considerable amount of wealth for a large number of rural households, which became potential buyers of urban real estate. In the 2000s, the government of W county, and most other local governments in China as well, started to expropriate and sell rural land to developers. Between 2000 and 2012, annual real estate investment in Changzhou Prefecture, where W county is located, increased from 0.6 billion yuan to 13.5 billion yuan, and the sales of real estate grew even faster (Figure 3). In the meantime, the average housing price had increased from less than 2,000 yuan per square metre to more than 6,000 yuan. The average price of land that the government offered to sell also shot up, from 1.4 million yuan per mu in 2007 to 3.7 million yuan per mu in 2013, suggesting that the local government could reap an enormous amount of revenue from land sales. As noted in the introduction, land sales across the country made up 50 per cent of local revenue between 2004 and 2013. In Changzhou, the dependence of local government on © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Urbanization and the Transition of Rural Industry in China 425 land sales was even higher than the national average, taking up a reported 80 per cent of the revenue of the prefecture in 2012 (Li 2014). Perhaps, then, it is no surprise that the local government has embraced the land revenue regime enthusiastically. It initiated land expropriation in the name of urban planning and urbanization. After land was purchased by a developer or industrial corporation, the local government would assist the developer in taking the land from the rural residents. In many cases, the local government would act alone and expropriate the land first, and then look for potential buyers. When I was conducting fieldwork in Z village in 2010, local officials paid frequent visits to the village to make sure that land expropriation went as planned. They forced village officials and their relatives to sign the consent form first and tried to neutralize any resistance from villagers. A township official told me that most of her colleagues were sent to villages as task forces to supervise land expropriation, and that this bore directly on their performance evaluation.14 The land revenue regime also amplified the power of local government, because it controlled key material and institutional resources in the regime, including land, bank loans, infrastructure funds, urban planning and real estate transactions. Impacts on Rural Industry The land revenue regime depends much less on industrial production than did local state corporatism. By turning rural land into urban areas, it has created a wide range of surplusgenerating activities including, but not limited to, infrastructure investment, the production of building materials, construction, real estate sales, mortgaging, house remodelling and urban services. These activities have fundamentally altered the rural landscape in W county. In 2002, there were 407 villages in W county. By 2012, that number had fallen to 246. In short, the government had turned 161 villages into urban areas, accounting for nearly 40 per cent of the total.15 By the time of my fieldwork in 2010, all of the villages between Z village and the city had disappeared due to urban expansion. In August 2010, the government notified the village that it would expropriate one third of the village area to build high-rise apartment buildings, and that it was only a matter of time before the rest of the village land would be expropriated. The separation of villagers from village resources. The disappearance of villages was an indication that villagers were separated from village resources. As noted previously, village land is owned collectively under the Chinese village system, and rural residents hold rights to farmland, housing land and other natural resources within the village. Rural industrialization did not change this relationship between villagers and village resources. For example, Z village no longer engaged in farming after it had turned all the farmland into factories in the early 2000s. However, it continued to be classified as a village in the official statistics and government documents, because it still held the ownership of the land, which allowed rural residents in the village to access land or share benefits arising from the land. In contrast, residents in an urban neighbourhood do not hold landownership, which belongs to the state. Thus by turning rural land into urban areas and rural residents into urban residents, the local government had separated villagers from village resources and seized the ownership of these resources; after which, local government could sell newly expropriated lands to developers and large corporations for revenue. 14 15 Interview no. 18, 10 September 2010. Data source: the Changzhou Statistical Yearbooks for 2002 and 2013. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 426 Shaohua Zhan After villages were turned into urban areas and rural residents lost access to village resources such as land, almost all of the small factories had to close. It is very difficult for the small factory owners to relocate elsewhere, not only because rent in other places is often too high for them to afford, but also because land in the village is associated with social resources, which are important to the success of the factories. For example, community social networks make it easier for rural enterprises to borrow money, obtain market information, exchange labour and access up-to-date technology (Liu 1995; Peng 2004). With land being expropriated, these social resources were also gone. I interviewed a few enterprise owners whose villages were already urbanized. They all told me that more than 95 per cent of the small enterprises in their villages had closed.16 In Z village, dozens of factories that were located in the to-be-expropriated area were planning to shut down. Most rural residents, the owners of rural enterprises in particular, were resentful of land expropriation because of its negative impacts on their livelihoods. I learned from my interviews and local online forums that at least five protests had been launched in W county, in September and October 2010, all due to land expropriation. In particular, there was a murder case that sparked social outcry. A middle-aged rural resident, who refused to move out of his house, which was scheduled to be demolished, was killed by a group of unidentified attackers while he was sleeping in the house at night. His family staged a public memorial at the roadside and accused both the real estate developer and the local government of this crime. The closing of rural small enterprises due to urban expansion has not been limited to W county or southern Jiangsu, but has been observed in many other areas undergoing urban expansion. In Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, urban expansion has swallowed surrounding villages and forced small enterprises in those villages to close, according to media reports and government documents (Ma 2011; Weiyang Industrial and Commercial Association 2011). In Zhengzhou, Henan Province, while the government was wooing large manufacturers such as Foxconn, it was forcing small rural factories to close by expropriating village land for urban expansion (Zhongyuan District government 2013). However, it should be noted that access to village resources such as land is a necessary rather than a sufficient condition for rural households to start industrial enterprises. Other factors, such as a good policy environment and favourable market conditions, must also be present. That so many rural households in southern Jiangsu were able to start rural enterprises should be attributed to local state corporatism during the early reform period, which provided savings, work experience, entrepreneurial skills and market information for rural residents. Under the land revenue regime, however, local governments threw their support behind very large corporations while discriminating against small enterprises. This created an adverse policy environment and unfavourable market conditions for village-based enterprises. Pro-large-scale industrial policy. In August 2014, more than 3 years after my first fieldwork, I returned to Z village to conduct a follow-up investigation. A dozen high-rise apartment buildings were now standing next to the village. Part of the village was still there, but it was almost encircled by high-rise buildings from every side. Many factories were still running. To my surprise, however, in contrast to the strong resentment in 2010 towards land expropriation, many owners now wanted their factories to be expropriated, because governmentsponsored expropriation would compensate their factories and provide them with an exit. The shift in attitude had much to do with the impacts of pro-large-scale industrial policy on these small enterprises, which made their sheer existence increasingly difficult. 16 Interview no. 48, 23 October 2010; and interview no. 49, 24 October 2010. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Urbanization and the Transition of Rural Industry in China 427 From the late 1990s onwards, industrial policy in China has been shifting consistently towards pro-large-scale. ‘Grasping the large and letting go the small’ (zhuada fangxiao in Chinese) was not only a slogan in the reform of state-owned enterprises, but became a guiding principle for all industrial policies. This can be seen from changes in national and local official statistics. While, in the 1980s and 1990s, the government collected data on small enterprises, in the 2000s they only included large enterprises whose annual output exceeded 20 million yuan. In other words, small enterprises became so unimportant that they were not considered worthy of being shown in the statistics. The trend towards supporting large enterprises in industrial policy has continued unabated to the present. In the late 1990s, W county established a systemic pro-large policy framework, which included the following aspects: (i) The government will establish a structural adjustment fund to help a few large enterprises with technological upgrading and the introduction of new lines of production and marketing. (ii) The government will establish more ad hoc funds for large enterprises, prioritize their credit needs and allocate at least 50 per cent of bank loans to them. (iii) The government will increase tax returns for large enterprises to the extent that one third of taxes will be returned at the end of year. (iv) Large enterprises will be exempted from a number of fees and will pay reduced management fees to the government. (v) The government will push to establish large enterprise corporations by merging and purchasing small enterprises, making arrangements for workers laid off in this process. The land revenue regime pushed pro-large industrial policy even further because it was believed that large enterprises would use land intensively and thus save land for urban expansion. The government of W county established a few new industrial parks, which only admitted large enterprises. To qualify for entry to the parks, an enterprise must invest at least 24 million yuan (about US$4 million). In practice, the scale of enterprises that were allowed into the industrial parks was often larger than the minimum criterion, according to my interviews with local officials.17 This was a common practice in southern Jiangsu and many other areas, and was highly approved of by the Ministry of Land and Resources in 2013 because of its economical use of land (Yang 2013). In recent years, W county has issued a new round of policies to attract super-large capital, preferably foreign capital, into its industrial parks.18 Pro-large industrial policy has further empowered already competitive large enterprises while weakening small rural enterprises. As a result, many small enterprises were verging on bankruptcy. According to my interviews, the problems facing these enterprises were legion: lack of bank credit, land expropriation, electricity shortages, the dominance of large enterprises, declining rates of profit, rising labour costs, unreasonable government regulations and so on.19 As a result, some of the small rural enterprises were willing to accept the compensation package offered by the government to close down their factories. In addition, under the land revenue regime, commercial banks poured much more money into large corporations and the real estate industry, leaving fewer loans for manufacturing. As a 17 18 19 Interview no. 68, 25 August 2014. Interviews nos. 68 and 70, 25 August 2014. Interview no. 52, 26 October 2010; and interview no. 59, 23 August 2014. Also see Zhan and Huang (2013). © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 428 Shaohua Zhan result, not only small factories but also medium-sized manufacturing enterprises found it difficult to obtain bank loans in southern Jiangsu and elsewhere (Minshang 2011). Urbanization on Shaky Ground The land revenue regime has been a major force behind ongoing rapid urbanization in China because the more rural land is urbanized, the more local revenue will be generated. In recent years, southern Jiangsu, including W county, made a plan to push urbanization to new heights. In April 2013, the State Council approved a document drafted by the governments of southern Jiangsu, which aims to increase the region’s rate of urbanization to 75 per cent by 2020.20 However, the process of urbanization based on the land revenue regime has produced adverse social and economic outcomes, making it increasingly unsustainable. Under local state corporatism in the 1980s and 1990s, rural industrialization incorporated the majority of rural residents into the accumulation regime through rural institutions that attached villagers to village resources. Under the land revenue regime, however, local governments separated villagers from village resources and excluded them from the most profitmaking activities. The previous small-scale, village-based, local resident-run enterprises were closed down and replaced by large-scale, industrial park-based and often foreign-invested industrial corporations. In other words, the rural industry that transformed the Chinese countryside during the 1980s and 1990s had been wiped out by land urbanization. Upon losing their jobs and enterprises, rural residents were deeply concerned about their future livelihoods and launched a series of collective actions to protest against land expropriation, according to my fieldwork and several other studies (O’Brien and Li 2006; Sargeson 2013; Chuang 2014; Zhang 2015). However, in the face of powerful local governments, the rural residents seemed unable to reverse the process of land revenue-based urbanization. In light of this, they shifted their strategy to fight for a better compensation package. Compensation After being pushed by a series of rural protests over the past decade, the government of W county provided rural residents with a compensation package that consisted of three parts. The first was social insurance for landless peasants (called shidi nongmin baozhang). The government established an insurance fund in 2006, which provided a monthly retirement stipend for rural residents who had lost their land and had reached retirement age (60 years old for males and 55 for females). The stipend, about 800 yuan (about US$130) a month at current prices, could only cover very basic living expenses, though it was much higher than those in hinterland provinces. The second part of the package consisted of urban apartments, which were used to compensate rural residents whose houses had been demolished as a result of land expropriation. A household of five in Z village could receive two two-bedroom apartments, but if it wanted to upgrade to three-bedroom apartments, it had to pay extra. A common strategy for rural households in Z village was to upgrade one apartment to three bedrooms, which would be used by the household, while leasing out the other for a subsidiary income. The third part was cash compensation for factories. As noted earlier, not every household in Z village owned factories, and thus this type of compensation only applied to a proportion 20 Document number Fa Gai Diqu [2013] No. 814; date 25 April 2013; available at http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/ 2013-05/06/content_2396729.htm. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Urbanization and the Transition of Rural Industry in China 429 of households, which was about one third in Z village. The size of a common factory in Z village is between 700 and 1,000 m2, and the government compensated with 330 yuan for 1 m2. That is to say, a factory owner could receive a total amount of compensation between 231,000 and 330,000 yuan (between approximately US$37,500 and US$53,500). After being compensated, most former rural households would have an extra apartment to rent out. A small number of rural residents, usually those who were better-off, even invested in urban real estate in the hope of reselling at a profit in the future. Some rural residents took jobs in urban service sectors: they either run a small business, mostly in the retail trade, or work for urban service companies such as supermarkets, hotels and restaurants. Unlike local state corporatism, however, the land revenue regime excluded the majority of the rural residents, and many urban residents as well, from the most profit-making activities, such as infrastructure construction, real estate development and management, mortgaging and large-scale industrial production. Facing little chance of upward mobility, many rural residents either took up low-paying odd jobs or did not work at all. An increasing number of them depended on government welfare and lived off a small amount of rental income. This is in stark contrast to the situation in the 1980s and 1990s, when rural residents actively participated in production and market competition, and created a growing number of industrial enterprises. Signs of decline. In February 2013, a media report by a major national newspaper estimated that 70–80 per cent of newly built apartments in Changzhou were unoccupied, and thus labelled it another ‘ghost city’ (Zhang 2013). Figure 3 above also showed that housing sales in Changzhou Prefecture, where W county is located, started to decrease in 2012. The grim outlook for the housing market directly affected government revenue. Between January and August 2014, W county had not sold a single piece of land to developers. The capacity of the land revenue regime in surplus generation seemed to have declined. A possible reason for this decline is that by closing down small private enterprises and excluding the majority of rural and urban residents from profit-making activities, land urbanization reduced effective consumer demand among rural residents, workers and small enterprise owners for urban real estate. Commenting on the economic problems of South Africa, Arrighi et al. (2010, 434–5) pointed out that, by removing the rural base of indigenous black populations and excluding the majority of them from jobs and profit-sharing, the country created high levels of unemployment and increased welfare expenditure, and thus reduced broad consumer demand in the domestic market. Under the land revenue regime, a similar process has been taking place: as former enterprise owners have lost factories and local rural residents have lost their jobs in those factories, a growing number of people in W county have become unproductive and welfare dependent. In order to cut welfare expenditure, the government of W county attempted to reduce pensions for landless peasants in 2007, but only met with fierce resistance from retirees, who occupied the major government buildings and shut down the government for 2 days. Under this pressure, the government reversed its course and even increased the pension benefits. W county is now facing a very difficult situation: on the one hand, it has to increase welfare expenditure to cover the populations who are newly urbanized; on the other, it is unable to sell land to developers to cover welfare expenditure due to the low demand for urban real estate. This is reminiscent of local state corporatism in the late 1990s, when it was unable to generate sufficient surplus to meet the demands of key actors in the regime, though the causes of the problem were very different. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 430 Shaohua Zhan Media reports suggest that what has happened in Changzhou is not a singular, but a general, phenomenon. The urban housing market started to slide throughout the country in 2014, particularly in small and medium-sized cities such as Changzhou (Zhao 2014). At the beginning of 2015, eager to revive the housing market and prolong the land revenue regime, local governments across the country issued another round of stimulation policies, including reductions in housing taxes, increases in subsidies and the offer of easy mortgages (Huang 2015). Whether the stimulation policies will work remains to be seen. However, based on the comparison between local state corporatism and the land revenue regime in this paper, if the land revenue regime does not change its current practices and involve the majority of the rural and urban residents in profit-making activities, it will not be able to sustain itself in the long run. CONCLUSION: RURAL INDUSTRY AND AGRARIAN TRANSITIONS In many respects, rural transition in W county of southern Jiangsu has been distinct and cannot be generalized to the rest of the country. For example, the level of rural industrialization in southern Jiangsu was much higher than that in most regions of central and western China. Therefore, the case of W county only shows a possible path of rural transition in China. Nevertheless, the post-reform experiences of W county, particularly the comparison between local state corporatism in the early reform period and the land revenue regime at present, could inform our understanding of rural transitions in China in general. First, the case of W county has revealed at least two logics in rural transition: the capitalist logic to maximize surplus generation and the logic of state power to increase revenue and control resources. The first logic led to the privatization of collective enterprises in the late 1990s, when the capacity of the collective TVEs to make profits declined. The logic also suggests that the current land revenue regime might be on the way out, as it is now generating less and less surplus. The second logic led to the establishment of both local state corporatism and the land revenue regime. This logic draws attention to the crucial role of local government in rural transitions in China. On one hand, local governments are the agents of policy implementation that serve to carry out central policies at the local level; on the other, they behave as rational actors who pursue their own interests. These two roles have simultaneously shaped local government action in rural transitions in China, giving rise to a dual-path model: a national path that reflects the national trend and changes in central policies, and a local path that reflects local government actions and local changes. Second, the assumption of a crucial role notwithstanding, local governments must work through rural institutions that define rural residents’ rights and entitlements. Thus the same purposive action of local government – for example, local revenue generation – could produce divergent outcomes as rural institutions vary. Under local state corporatism, rural institutions such as collective landownership, which tied villagers to village resources, resulted in rural industrialization in the 1980s and 1990s involving the majority of the rural residents in W county. Under the current land revenue regime, however, in the process of land urbanization, local governments have separated villagers from village resources and excluded them from the most profit-making activities, leading to the replacement of village-based rural industry by a small number of large industrial corporations. Third, while the land revenue regime has provided rural residents with a compensation package in recognition of their previous rights to village resources, it has not established a set of institutions to mobilize rural residents to work and hence contribute to the new regime and share the benefits of economic growth. As a result, an increasing number of them have © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Urbanization and the Transition of Rural Industry in China 431 become welfare dependent and/or are relying on a small amount of rental income, or are taking up low-paying service jobs. This undercuts the capacity of the regime to generate sufficient surplus due to a lack of consumer demand for urban real estate, particularly in small and medium-sized cities such as Changzhou. If it cannot revive its ability to generate surplus, it is probable that the current land revenue regime will be phased out and replaced by a new accumulation regime, as happened to local state corporatism in the 1990s. REFERENCES Arrighi, G., N. Aschoff and B. Scully, 2010. ‘Accumulation by Dispossession and Its Limits: The Southern Africa Paradigm Revisited’. Studies in Comparative International Development, 45: 410–38. Bernstein, H., 2010. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change. Hartford, CT: Kumarian Press. Bramall, C., 2007. The Industrialization of Rural China. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Byrd, W.A. and Q. Lin, eds, 1990. China’s Rural Industry: Structure, Development, and Reform. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Chuang, J., 2014. ‘China’s Rural Land Politics: Bureaucratic Absorption and the Muting of Rightful Resistance’. The China Quarterly, 218: 1–21. Edin, M., 2003. ‘Local state corporatism and private business’. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 30 (3–4): 278–95. Harvey, D., 2003. The New Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Huang, Y., 2008. Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics: Entrepreneurship and the State. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Huang, M., 2015. ‘Difang xinzheng yu datong loushi rendu ermai’ [’New local rescue policy attempts to break the bottleneck of the housing market’]. Changjiang ribao [Yangtze River Times], 2 February, http://www .changjiangtimes.com/2015/02/496707.html (accessed 1 May 2015). Li, S., 2014. ‘Dangbao touban fawen haozhao maifang, Changzhou jiushi weihe ruci jiqie’ [‘The Party paper called for house purchases in the headline, why Changzhou was so eager to save the housing market’]. Pengbai xinwen [The Paper], 17 July, http://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1256305 (accessed 4 January 2015). Lin, N., 1995. ‘Local Market Socialism: Local Corporatism in Action in Rural China’. Theory and Society, 24 (3): 301–54. Liu, S., 1995. ‘Xiangzhen qiye fazhanzhong dui feizhengshi shihui guanxi ziyuan de liyong’ [‘Use of informal social networks resources in the development of TVEs’]. Gaige, no. 2: 62–8. Ma, J., 2011. ‘Shiye chaqian de jiti yongdi zhihuo’ [‘Questions on Land for Enterprises during Urban Redevelopment’], Diyi caijing ribao [First Financial Daily], 14 December. McMillan, J. and B. Naughton, 1992. ‘How to Reform a Planned Economy: Lessons from China’. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 8 (1): 130–43. Minshang, 2011, ‘Sunan minying qiye zhinan’ [‘Difficulties facing private enterprises in southern Jiangsu’], Hexun website, http://news.hexun.com/2012-01-13/137253819.html. MOAC (Ministry of Agriculture of China), 2003. China TVEs Statistical Data: 1978–2002. Beijing: Zhongguo nongye chubanshe. Naughton, B., 1995. Growing Out of the Plan: Chinese Economic Reform, 1978–1993. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. NBSC (National Bureau of Statistics of China), 1985. China Rural Statistical Yearbook 1985. Beijing: China Statistics Press. NBSC (National Bureau of Statistics of China), 1996. China Rural Statistical Yearbook 1996. Beijing: China Statistics Press. NBSC (National Bureau of Statistics of China), 1997. China Rural Statistical Yearbook 1997. Beijing: China Statistics Press. Nee, V., 1992. ‘Organizational Dynamics of Market Transition: Hybrid Forms, Property Rights, and Mixed Economy in China’. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37 (1): 1–27. Nee, V. and S. Opper, 2012. Capitalism from Below: Markets and Institutional Change in China. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Nolan, P. and F. Dong, eds, 1990. Market Forces in China: Competition and Small Business – The Wenzhou Debate. London: Zed Books. O’Brien, K.J. and L. Li, 2006. Rightful Resistance in Rural China. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Oi, J.C., 1992. ‘Fiscal Reform and the Economic Foundations of Local State Corporatism in China’. World Politics, 45 (1): 99–126. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 432 Shaohua Zhan Oi, J.C., 1999. Rural China Takes Off: Institutional Foundations of Economic Reform. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Peng, Y., 2002. ‘Zhongguo de cunzheng gongye gongsi: suoyouquan, gongsi zhili yu shichang jiandu’ [‘China’s TVE industrial corporations: ownership, enterprise governance and market supervision’]. Tsinghua Sociological Review, no. 4: 1–19. Peng, Y., 2004. ‘Kinship Networks and Entrepreneurs in China’s Transitional Economy’. American Journal of Sociology, 109 (5): 1045-74. Pei, X., 2002. ‘The Contribution of Collective Landownership to China’s Economic Transition and Rural Industrialization’. Modern China, 28 (3): 279–314. Putterman, L., 1993. Continuity and Change in China’s Rural Development: Collective and Reform Eras in Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Qian, Y., 2000. ‘The Process of China’s Market Transition (1978–1998): The Evolutionary, Historical, and Comparative Perspectives.’ Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 156 (1): 151–71. Rawski, T.G., 1994. ‘Chinese Industrial Reform: Accomplishments, Prospects, and Implications’. The American Economic Review, 8 (2): 271–5. Sargeson, S., 2013. ‘Violence as Development: Land Expropriation and China’s Urbanization’. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 40 (6): 1063–85. Shao, Y., 2010. ‘Guanyu tudi caizheng yu caishui tizhi gaige wenti zongshu’ [‘A review on land revenue and the issues of the fiscal and tax reform’]. Review of Economic Research (China), 32 (24): 36–45. Walder, A.G., 1995. ‘Local Governments as Industrial Firms: An Organizational Analysis of China’s Transitional Economy’. American Journal of Sociology, 101 (2): 263–301. Webber, M., 2008. ‘Primitive Accumulation in Modern China’. Dialectical Anthropology, 32 (4): 299–320. Weiyang Industrial and Commercial Association, Xi’an, 2011. ‘Tuidong zhongxiao qiye pingwen fazhan de diaocha yu sikao’ [‘Investigation and Suggestions on Promoting the Development of Small and Median-Scale Enterprises’], website of Weiyang District government, http://www.weiyang.gov.cn/dwgk/qwml/rmtt/gsylhh/dyhnk/ dcyj/31223.shtml (accessed 21 July 2011). Wen, T., 2011. Jiedu Sunan [Explaining Sunan]. Suzhou, China: Suzhou daxue chubanshe. Whiting, S.H., 1996. ‘Contract Incentives and Market Discipline in China’s Rural Industrial Sector’. In Reforming Asian Socialism: The Growth of Market Institutions, eds J. McMillan and B. Naughton, 63–110. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Wong, C.P., 1988. ‘Interpreting Rural Industrial Growth in the Post-Mao Period’. Modern China, 14 (1): 3–30. Yang, Y., 2013. ‘Kan sunan xiandaihua shifanqu jianshe zhong de yongdi fangshi zhi bian’ [‘Eyes on changes in the way of land use in southern Jiangsu’s modernization demonstration zone’]. Zhongguo guotu ziyuan bao [China Land and Resources Daily]. 12 September, http://www.gtzyb.com/yaowen/20130912_48696.shtml (accessed4 January 2015). Zhan, S. and L. Huang, 2013. ‘Rural Roots of Current Migrant labor Shortage in China: Development and Labor Empowerment in a situation of Incomplete Proletarianization’. Studies in Comparative International Development, 48 (1): 81–111. Zhang, L., 2013. ‘Lunwei guicheng di’er, Changzhou chanye zhuanxing cuotou fangdichan’ [‘Becoming the second ghost city, Changzhou wrongly turned to real estate in economic restructuring’]. Zhongguo jingyibao [China Business Journal], 25 February: B9. Zhang, M., 2014. ‘Tudi caizheng zaichuang xinggao, Juzai moshi jidai gaibian’ [‘Land revenue reached new high, urgent to change the debt model’]. Jinrong shibao [Financial News], 15 July: 5. Zhang, X. and P. Yuan, 2003. Zhongguo xiangzhen qiye chanquan gaige beiwanglu [Memos on TVEs’ Ownership Reform in China]. Beijing: Social Science Academic Press. Zhang, Y., 2015. ‘Daqingchang: zhongguo de quandi yundong jiqi yu yingguo de bijiao’ [‘Great clearance: China’s enclosure movements in comparison with that of England’]. Journal of China Agricultural University (Social Sciences), no. 1: 19–45. Zhao, J., 2014. ‘Fangdichan dimi, Difang caizheng kongzhuan taitou’ [‘Downward housing markets led the local government to fake revenue numbers’]. Economic Information Daily, 29 September: A01. Zhongyuan District government, 2013. ‘Zhengzhou xiqu shimin gonggong wenhua fuwuqu dalicun fanwei nei qiye chaiqian gongzuo shengli zaiji’ [‘An Imminent Victory on Demolishing and Relocating Enterprises in Dali Village Located in Zhengzhou West Cultural Service District’], http://www.zhongyuan.gov.cn/sitegroup/root/ html/90925e812839fd0e012841053a6101e3/20130607085843790.html. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Copyright of Journal of Agrarian Change is the property of Wiley-Blackwell and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.