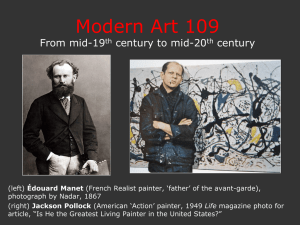

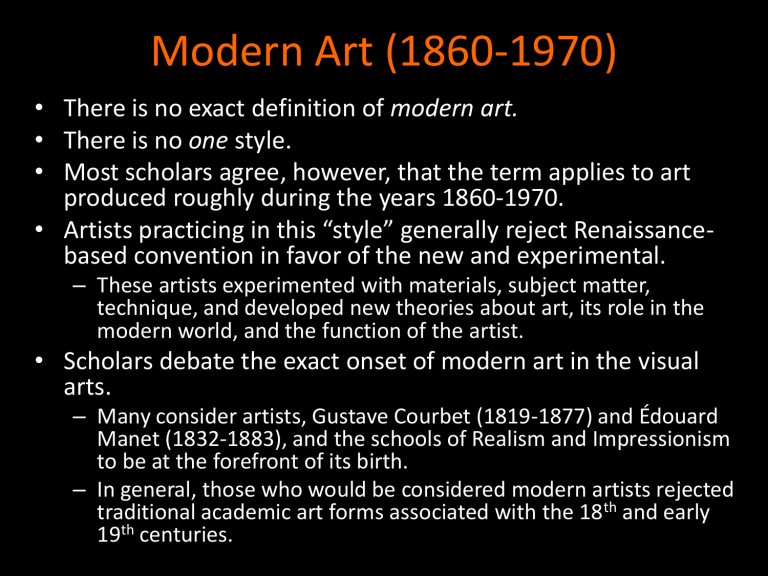

Modern Art (1860-1970) • There is no exact definition of modern art. • There is no one style. • Most scholars agree, however, that the term applies to art produced roughly during the years 1860-1970. • Artists practicing in this “style” generally reject Renaissancebased convention in favor of the new and experimental. – These artists experimented with materials, subject matter, technique, and developed new theories about art, its role in the modern world, and the function of the artist. • Scholars debate the exact onset of modern art in the visual arts. – Many consider artists, Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) and Édouard Manet (1832-1883), and the schools of Realism and Impressionism to be at the forefront of its birth. – In general, those who would be considered modern artists rejected traditional academic art forms associated with the 18th and early 19th centuries. Becoming Modern • Modernism refers to the period from 1850 to 1960. • Modern Art (arguably) begins with Realism and ends with Abstract Expressionism. • Period characterized by a tremendous amount of different artistic styles. Gustave Courbet, The Stone Breakers, 1849. Oil on canvas, 65” × 128”× 12134”. Now destroyed. Becoming Modern Realism (1840-late 19th century) • Social change, triggered by the Industrial Revolution, leads to greater emphasis by artists on realism of subject matter. • The role of the artist changes-the artist is now a social commentator, a bohemian living on the outskirts of society. Gustave Courbet, The Meeting (Bonjour M. Courbet), 1854. Oil on canvas, 52” x 59.3”. Musée Fabre de Montpellier, Australia. Becoming Modern • The popularization of photography is also responsible for the move toward Realism in painting. • Artists were now competing with a machine in attempt to depict subjects in objective reality. Announcing the invention of photography (the daguerreotype) at The Joint Meeting of the Academies of Science and Fine Arts in the Institute of France, Paris, August 19, 1839, unsigned engraving. Photography • 1839 Daguerre demonstrates to the public the daguerreotype-a technology that permanently affixed an image of the world on a flat surface • Some painters embraced this new technology (Edgar Degas and Thomas Eakins) experimenting with photography and using it as a tool; while others, artists and critics, alike were skeptical • Photography was not included within the various important art exhibitions Louis-Jacqyes-Mandé Daguerre, The Artist’s Studio,1837. Société Française de Photographie, Paris. Photography • Almost immediately, photographers began to exploit the visual and creative nature of this new medium. • Many, like Daguerre, look to master painters from the Renaissance and Baroque for inspiration. Pieter Claesz, Still-Life with Skull and Writing Quill ,1628. Oil on wood, 9 ½” x 14 1/8”. Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC. – Seen here, Daguerre mimics Claesz’s still life to create his own, modern version. Louis-Jacqyes-Mandé Daguerre, The Artist’s Studio,1837. An early daguerreotype taken in the artist’s studio. Société Française de Photographie, Paris. Photography • Photography was used to document (or re-enact) important historical events not unlike paintings prior to its invention. Re-enactment of the October 16, 1846 ether operation. Daguerreotype by Southworth & Hawes. Library of Congress. Rembrandt, Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp, 1632. oil on canvas, 85.2” × 66.7”. Mauritshuis, The Hague. Thomas Eakins, The Gross Clinic, 1875. Oil on canvas 8’x 6’6.“ Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA. Photography • Muybridge (1830-1904), originally a landscape photographer, became best known for his ground-breaking work in animal locomotion-he used photography to capture and understand motion (of horses, humans, etc.). – His technique used multiple cameras to capture a horse galloping. Eadweard Muybridge, The Horse in Motion,187887. Wet-plate photograph. • Humans in motion. Eadweard Muybridge, The Body in Motion, c. 1878-87. Wet-plate photograph. Chinese Horse, c.15,000-10,000 BCE. Lascaux Caves, France. First discovered 1940. • Prior to Muybridge’ studies, painters did not fully understand the physical movement of horses (for example). • Before Muybridge, painters did not know that while running, all of a horse’s hooves leave the ground. – Historically, this resulted in rather unbelievable renditions of a horse in motion, often referred to as the “hobby-horse”. – Artists, including the Renaissance master, Leonardo da Vinci, studied horse for a better understanding of how they move. – This was not fully understood until Muybridge’s efforts. Leonardo da Vinci, Study of Horses, (details from the artist’s notebook.), 1494. Silverpoint on prepared paper. Royal Library, Windsor. Eadweard Muybridge, The Horse in Motion,1878-87. Wetplate photograph. • Muybridge’s findings enabled painters to present more believable representations of animals and humans in motion. • Artists like Degas reference photography for various reasons, including painting anatomically correct animals in motion. Edgar Degas, The Jockey, 1889. Pastel on paper, 12 ½” x 19 ¼”. Philadelphia Museum of Fine Art, PA. Photography • Introduced to the public in 1839, photography experienced great success and popularity with the general public. • Still, photography faced many critics who rejected its efforts to become considered a fine art. • This lithograph demonstrates the debate of the medium and its status as technical Honorè Daumier, Nadar Elevating Photography to the Height of Art, 1862. process or fine art. Lithograph, 10 11/16” x 8 ¾”. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photography • To advocate photography’s acceptance as a fine art, photographers copied well-known paintings to demonstrate its aesthetic potential. Thomas Couture, Romans of the Decadene, 1847. Oil on canvas, 185.8” x 303.9”. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Oscar Rejlander, The Two Ways of Life, 1857. Combination albumen print. Royal Photographic Society, England. Photography • Photographers opened portrait studios and often entertained (and competed for) wellknown personalities to add to their collection. • Photographers often referenced famous portraits while composing photographs of their subjects. Nadar, Portrait of Sarah Bernhardt,1864. Photograph, 9 5/8” x 9 3/8”. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. – Here, Nadar takes the ¾ pose used by Leonardo when painting the Mona Lisa. Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, 1503-06. Oil on poplar wood, 30”x21”. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Schools of Modern Art Realism (1840-late 19th century) • The Realist movement thrived in France from approximately 1840 until the late nineteenth century. • Realists sought to express a truthful and objective vision of contemporary life. • Realists began to challenge conventions upheld by the academy experimenting with subject matter, process, and interjecting social commentary into their work. • French painter, Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), is considered the leader of the Realist movement. – Artists like Édouard Manet would inherit his innovative style. Gustave Courbet, A Burial at Ornans, 18491850. Oil on canvas, 123.6” x 261”, Musee d'Orsay, Paris. Exhibited at the 1850–1851 Paris Salon created an "explosive reaction" and brought Courbet instant fame. Fig. 24.1 Becoming Modern • Realism is a response to its times. – It is a rejection of Romanticism. – It is a response to photography. – Its is a response to the revolutionary attitude of the day. – It is a quest for truth. • Realism links Romanticism with Impressionism. Schools of Modern Art Realism (1840-late 19th century) • Courbet’s A Burial at Ornans demonstrates what Realist artists sought: – Courbet paints an actual event, one that is more personal than historically important, the death of a relative. – He uses the ordinary people that attended this event. – He paints them as they were, not beautiful or idealized, but accurate. • Critics argued his faces were caricature and accused the artist of “a deliberate pursuit of ugliness.” – The painting is a real life depiction of Ornans- its people and events. Gustave Courbet, A Burial at Ornans,18491850. Oil on canvas, 123.6” x 261”, Musee d'Orsay, Paris. Schools of Modern Art Realism (1840-late 19th century) • Critics rejected the work based on its subject matter– Academic convention ruled that large canvases (this painting measures 10 feet by 22) was reserved for historically important events and people (battle scenes, religious imagery, political leaders), not ordinary life. • Courbet attempts with this piece to “thrust himself into the grand tradition of history painting”. Gustave Courbet, A Burial at Ornans,18491850. Oil on canvas, 123.6” x 261”, Musee d'Orsay, Paris. Schools of Modern Art Realism (1840-late 19th century) • In addition, critics rejected the style in which it was painted. – Courbet asserts the paint’s texture. • Courbet employs texture to make the image painted seem more tangible and NOT to explore Romantic notions of the sublime. Gustave Courbet, A Burial at Ornans, 18491850. Oil on canvas, 123.6” x 261”, Musee d'Orsay, Paris. Becoming Modern Realism (1850-late 19th century) • Partly responsible for the movement’s name, The Painter’s Studio was rejected by the Exposition of 1855 • In response Courbet opens his own exhibition, "Le Realisme” or “Exhibition of Realism” Gustave Courbet, The Painter’s Studio: A real allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life, 1855. Oil on canvas, 11’ 10 ¼ x 19‘ 7 ½ “. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Schools of Modern Art Characteristics of Realist paintings include: • Commitment to verisimilitude (the appearance of truth in painting) • Rendering of the everyday (person, experience) • Rejection of the theatrical, dramatic, or ceremonial • A replacement of convention and the grandiose for the commonplace • Rejection of the ideal for the familiar • Rejection of universal truths • Debate with conventional aesthetics “The Painter of Modern Life” • Written in 1860 by French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), “The Painter of Modern Life” summarizes the new role of the artist. • Although the poet did not know the painter Édouard Manet (1832-1883) while writing the article, the two became close friends and Manet representative of Baudelaire’s “painter of modern life.” • Manet painted in a style all his own oscillating between Realism and Impressionism (he does not belong specifically in any one category, he painted in both styles) Édouard Manet, Autoportrait à la palette (Self-Portrait with Palette), 1878/1879. Oil on canvas, 33” × 26”. Private Collection, Greenwich, Connecticut Becoming Modern • Considered by many to be the first modern painter, Manet’s paintings became watershed moments in the history of art and inspired generations of avant-garde artists. • His Déjeuner sur l’herbe, introduced to the public at the Salon des Refusés in 1863. – The Salon des Refusés, or “salon of the refused” was an exhibition of works rejected by the Paris Salon. – After artists protested the 3,000 paintings rejected by the Salon, Emperor Napolean III ordered the works to be displayed in the Salon des Refusés. – Even though the official Salon rejected these works, the attention established Édouard Manet, Déjeuner sur l’herbe the “rejected” artists as the leaders of (Luncheon on the Grass), 1863. Oil on modern art’s avant-garde. canvas, 6’9 1/8” x 8’ 10 ¼”. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Becoming Modern • Although he was considered the leader of the avantgarde, Manet DID seek official acknowledgment from the Salon. • Manet was a realist who sought to obtain recognition working within the conventions of the Salon-but in a modernized way. • In Déjeuner sur l’herbe he quotes from Renaissance artists before him. Édouard Manet, Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass), 1863. Oil on canvas, 6’9 1/8” x 8’ 10 ¼”. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Titian,(formerly thought to be by Giorgione), The Pastoral Symphony (Fête Champêtre), c. 1510. Oil on canvas, approx. 3' 7" x 4' 6” . Musée du Louvre, Paris. Édouard Manet, Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass), 1863. Oil on canvas; 6’9 1/8” x 8’ 10 ¼”. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Marcantonio Raimondi, The Judgment of Paris, c. 1510-18. Engraving based on Raphael cartoon, 11 ½” x 17 3/16”. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Becoming Modern • Manet continued to scandalize Paris with with the exhibition of Olympia at the 1865 Salon. • With this piece, Manet joined many artists before him in taking on the subject of the female nude. Édouard Manet,Olympia,1863-65. Oil on canvas, 4’3” x 6’2 ¾”. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Giorgione, Sleeping Venus, c. 1510. Oil on canvas, 42.5” x 68.9”. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden • The subject of the reclining female nude was first explored in 1510 by Renaissance master, Giorgione (1477/8 -1510). • Upon completing the background of Sleeping Venus after the artist’s death, Titian (1488/90-1576), a student of Giorgione, created his own Venus and thus began a long history of the female nude depicted in a landscape. • Titian’s Venus of Urbino takes Giorgione’s subject (the female nude) and domesticates her, brings her indoors. Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538. Oil on canvas 47” x 65”. Uffizi, Florence. Giorgione, Sleeping Venus, c. 1510. Oil on canvas, 42.5” x 68.9”. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden Francisco Goya, The Nude Majas, 1792. Oil on canvas, 38.6” x 75.2”. Prado Museum, Spain. • With Olympia in 1863, Manet joins the ranks of the many painters before him who have taken the female nude as subject. Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538. Oil on canvas 47” x 65”. Uffizi, Florence. Édouard Manet,Olympia,1863-65. Oil on canvas, 4’3” x 6’2 ¾”. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Becoming Modern • What offended the public was not Olympia’s nudity. • It was her confrontational stare implicating the audience, the viewer as client and voyeur. • Manet also uses the objects within the painting to identify Olympia’s profession as a courtesan or prostitute. – It may not seem obvious to us today but in the 19th century the signs included: • orchid in her hair • the replacing of the dog (a symbol of fidelity) with a cat (representative of female anatomy and a cat-house or brothel) • the bouquet of flowers (also disguised symbolism for female genitalia) • the bracelet, the necklace, the Oriental shawl, and pearl earrings all signify wealth, opulence, and excess. Édouard Manet,Olympia,1863-65. Oil on canvas, 4’3” x 6’2 ¾”. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Becoming Modern • Manet’s Olympia however defied traditional representations of the female nude. • Manet uses these traditional subjects to challenge convention. • Here, he modernizes the nudehe paints the portrait of a recognizable woman, Victorine Meurent, a painter and favorite model of Manet, and presents the nude in a much more obvious way. Édouard Manet,Olympia,1863-65. Oil on canvas, 4’3” x 6’2 ¾”. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Becoming Modern • The in-your-face presentation of the subject was not all that offended the audience. – The positioning of Olympia’s hand over her pubic area was unlike any nude before. • The realism of the piece was what most offended its audience. • Manet’s work is unapologetic in its handling of the subject matter, paint, and implication of the spectator. Édouard Manet, (detail) Olympia,1863-65. Oil on canvas, 4’3” x 6’2 ¾”. Musée d'Orsay, • In comparison to Giorgione and Titian, Manet’s Olympia is vulgar, she has agency, takes possession/control of her body and access to it. • Unlike the Renaissance Venus, she is not docile but confrontational. • The classical subject of a reclining Venus has been replaced by Manet with an unidealized, modern Édouard Manet, (detail) prostitute of Paris. Olympia,1863-65. Oil on canvas, 4’3” x 6’2 ¾”. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Giorgione, Sleeping Venus, c. 1510. Oil on canvas, 42.5” x 68.9”. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538. Oil on canvas 47” x 65”. Uffizi, Florence. • Reactions to Manet’s Olympia made headlines. • Critics were certainly not shy about publishing their sentiments, as seen here in this caricature. Newspaper caricature in response to Manet’s Olympia. Becoming Modern • Stylistically, Manet was criticized for his flattening of the picture plane, unflattering painting of the female form, and lack of illusionistic depth. – Manet uses contours to create volume within the figure. – Olympia’s startlingly white skin is a collection of angles pressed against the picture plane. – Her flatness troublingly unsettling for even Courbet. Édouard Manet,Olympia,1863-65. Oil on canvas, 4’3” x 6’2 ¾”. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Outside Influences • Aside from photography, Japanese prints represent the most prominent influence on 19th century painters. • In 1854, Commodore Matthew Perry opens/forces Japanese ports open to West. • Artists are attracted to the sharp angles, bold, snap-shot cropping, nearflat arrangement, and brilliant colors defined by contour line of Japanese artists. • Emphasizes it is NOT pictorial truth but artistic integrity. Andō Hiroshige, Moon Pine at Ueno from One Hundred Views of Famous Places in Edo, 1857. Color woodcut, 13 ¾” x 8 5/8”. The Brooklyn Museum, NY. Outside Influences • Manet publishes his influences here in his portrait of Èmile Zola (1840-1902), the French writer. – Zola was a friend and supporter, his tract on Manet is included in the portrait (on the desk). – Zola wrote L’Evénement on the Salon of 1866, a vigorous defense of Manet’s work aligning the artist with the avant-garde dogma, “Art for art’s sake.” • In the background of Zola’s library is Manet’s own Olympia, a detail of Bacchus by the Spanish Baroque painter Velázquez (15991660), and a Japanese print. Édouard Manet, Portrait of Èmile Zola, 1868. Oil on canvas, 57 1/8” x 44 7/8.” Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Becoming Modern • Studies under one of Ingres’ students • Around 1865, enters Manet’s circle • Work takes on new style • Contemporary themes of excitement of everyday life • Cropped images • Voyeuristic views Edgar Degas, The Orchestra of the Paris Opera, 1868-1869. Oil on canvas, 22 ¼” x 18 3/16.” Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Fig. 24.3. Hiroshige, Sudden Shower Over Shin-Ohashi Bridge and Atake, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857. Vincent van Gogh, Bridge in the rain (after Hiroshige), 1887 (from Japonaiserie). Oil on canvas, Becoming Modern • American Realism • Artist studies in Paris, returns to Philadelphia • Turns sports figure into modern hero • Studies perspective, anatomy, and boats to capture minute details Thomas Eakins, Max Schmidt in a Single Scull, 1871. Oil on canvas, 32 ¼” x 46 ¼.” Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. Fig. 24.12. Becoming Modern • Contemporary of Eakins • Studies Paris, 1866-1867 • Begins career as magazine illustrator • Paintings are iconic moments of a simpler life • Images are frozen moments • Figures carefully outlined • Embodies country’s lost innocence • Nostalgic appeal for return to values Winslow Homer, Snap the Whip, 1872. Oil on canvas, 22 ¾” x 36 ½.”Butler Institute of American Art, Ohio. Fig. 24.13. Becoming Modern • Manet’s later work, demonstrates the uniqueness of his style. • Never solely dedicated to the Realist style, nor Impressionism, Manet is best described as an enigmatic Realist. • His Bar at the Folies Bergere demonstrates how the artist oscillates between the two schools combining subject matter and painterly style. • His barmaid demonstrates the alienation that was symptomatic of modernity. • His brushstrokes are evidence of the artist’s constant experimentation. • His work would become primary inspiration for a younger generation of artists that would become known as the Impressionists. Édouard Manet, The Bar at the Folies Bergere, 1882. Oil on canvas, 37.8” x 51.2”. Courtauld Institute of Art, London