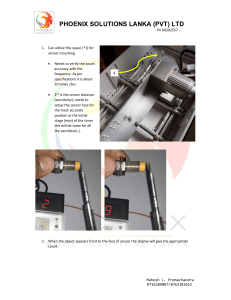

Sensor Technology Interface Final Report Sponsor FitnessMetrics, LLC ECE 480 Team 1 Nick Henry Kelton Ho Nick Huff Robert Pollum Brian Wirsing Executive Summary Modern society is interlinked through a network of not only people, but their respective electronic devices as well. The devices permeate people’s lives so thoroughly that it is rare to see someone without an electronic device, be it a watch, a cellphone, a computer. Yet, these devices have not even touched the surface of what is possible. Recent research has delved into so called “smart” devices. These smart devices are ordinary, everyday gadgets that together with sensors widely broaden the possibilities of what is capable. However, there are just as many types of sensors as there are electronic devices. To communicate with each of these sensors through custom hardware is an expensive and tedious process. Hence, there is a need for a system that can flawlessly connect different sensors and make sense of this data. We have developed an open source microcontroller on which users can connect a wide variety of sensors to their smartphone. Our design creates a cheap and easy interface in which everyday people can connect the sensors in their lives while making that data meaningful. The microcontroller paired with the included Android app will give people the tools they need to bridge the data collected by electronics with the reality, widening the gap for what is real and possible. Acknowledgments: The scope for this project was wide and the possibilities far. Without the support of the sponsors, facilitator, and others, this project could not have been completed. Specifically, the team would like to thank: ● Our sponsors Anthony Carriveau and Bernie Holmes for providing funding, advice and their continuing support for a developing project. ● Andy Rubin and Massimo Banzi for allowing their respective Android platform and Arduino microcontrollers to be open-sourced and available for all. ● Our families for their support through a time-consuming semester. 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Introduction and Background 4 Introduction 4 Background 5 Chapter 2 - Solution Exploration and Selection 7 Section 1 - FAST Diagram 7 Section 2 - House of Quality 8 Section 3 - Budget 9 Section 4 - GANTT Chart 12 Chapter 3 - Technical Work Performed 15 Section 1 - Hardware Design Efforts 15 Section 2 - Hardware Implementation 16 Section 3 - Software Design Requirements 20 Section 4 - Software Implementation 20 Subsection 1 - Microcontroller Program 21 Subsection 2 - Android Application 25 Chapter 4 - Testing 32 Section 1 - Hardware Testing 32 Section 2 - Software Testing 33 Chapter 5 - Conclusions 36 Section 1 - Final Prototype 36 Section 2 - Cost 36 Subsection 1 - Prototype Cost 36 Subsection 2 - Production Cost 37 Section 3 - Schedule 37 Section 4 - Findings 37 Section 5 – Future Work 38 Appendix 1 - Technical Roles Nick Henry 40 40 2 Kelton Ho 41 Nick Huff 42 Robert Pollum 43 Brian Wirsing 44 Appendix 2 - References 47 Appendix 3 - Technical Attachments 47 3 Chapter 1 – Introduction and background Introduction Sensors are becoming increasingly prevalent in our everyday lives. Members of society are surrounded by various kinds of sensors that send and receive information. The protocols used by these sensors can vary drastically; variations include sensors that are wired or wireless, analog or digital. Viewing the data from all of these sensors was shown to be of high priority. Usually, each sensor is connected to a unique user interface which displays that sensor’s information. Therefore, in order to view the information from five different sensors, one needs to get it from five different UIs, which is not ideal. This causes clutter and creates a hassle for users who are increasingly trying to become more connected to their personal networks. One solution to this problem is to consolidate the information from these sensors onto one platform, which can then display all of the sensors’ data into one UI. This platform consists of two components: a sensor interface (SI) to receive the sensor information, and an Android app to display the information to the user. Having a user friendly UI will aid in adoption while programmers can add new features. Since its inception, the Sensor Interface has been an open source platform, creating the unique advantage of possibly having thousands of developers all working on this product. By designing with the open-source philosophy in mind, people can contribute their personal skills and creativity in order to create a one-of-a-kind product that will continuously evolve into a more advanced and efficient platform. The constraints of the Sensor Technology Interface Project were broad, and left a lot of room for creative input. The four main constraints were cost, size, power, and types of sensors. Keeping the microcontroller open source was also a high priority so that others can build off of what the project will start. Low cost was of a high priority as keeping the Sensor Interface low cost allows for larger adoption rates and long term lower costs once they are hopefully mass produced. We are hoping to sell 10,000+ of these microcontrollers within the next few years with an expected cost around $25. As more people adopt the microcontroller into their everyday lives, the cost could potentially lower even further. When a portable device is being designed, the size-to-power ratio will always be of concern. Designing with the small size in mind allows the microcontroller to be used in 4 applications where larger designs would not be feasible . This microcontroller could be put into appliances, toys, clothes, etc. A smaller size remains a higher priority over power consumption, but power use is still important. The design allows the microcontroller to last several months on one charge, which will allow it to be kept in use for long periods of time without any form of maintenance. Having the microcontroller constantly communicate its data over Bluetooth drastically reduces its battery’s lifetime. Therefore, the microcontroller has local storage in the an SD card slot. This enables the microcontroller to store data and send it in intervals specified by the user. Background On the hardware side, there are a number of products currently on the market that can perform some of the requirements of this project. The RFDuino is the best example [1]. The RFDuino is a small microcontroller with a built-in Bluetooth module. It is able to perform many of projects functions, such as communicating with wired and wireless sensors, transmitting information to an Android device via Bluetooth, and storing data to an SD card. However, the main problem with this solution, along with many others like it, is that the RFDuino must be programmed to perform this operation. This makes the RFDuino an impossible solution for users who don’t know how to program, and an impractical solution for those that can program, but don’t want to. A better product would already have the code pre-compiled, the input ports clearly labeled, and require little to no setup from the user. On the software side, there are some Android apps that interface with certain microcontrollers. One example is ArduDroid [2]. This app communicates with an Arduino microcontroller via a Bluetooth connection. Using ArduDroid, users can read data coming from an Arduino board, send data back to the Arduino board, and configure Arduino GPIO pins to function as either input or output. The main problem with this app is that it does not perform the specific functions required, such as listing multiple Arduino port outputs, saving data, and graphing data history. To accomplish these tasks, an app should be designed from scratch with these functions in mind. The sensor interface will ultimately work with smart phones, specifically Android devices, which pride themselves on being sleek, stylish, and above all, open. The portability and 5 creative nature of the design needed to match the idea of the internet being in more and more products. The bulk of our design was not our only convenience issue; The design should also not require constant maintenance in the form of charging or changing batteries too frequently. All of these features would be beside the point if no one had an interest in using this device, so we had to create interesting functionality and innovative features to draw people into wanting to have this attached to their phones at all times. In order to implement this functionality, a list of required parts for the microcontroller to interface with was created. There will need to be many forms of inputting and outputting data via wired and wireless connections. This data must be able to be stored until it is able to be buffered and sent to the phone. The data collected had to have a reasonable level of quality and real time streaming capabilities which meant time stamping all of the information collected as well as sampling frequently in order to get a smooth plot of whatever information a sensor might be transmitting. All of this data would mean nothing without a user interface for the Android devices. The Android device must be able to input the data from the microcontroller and organize and display it in a way that is convenient for the user. Once it has displayed this data it will then upload to a cloud form of storage to be further processed. There are many other features that an optimal, but not realistically viable given our time frame and other constraints. 6 Chapter 2 – Solution Exploration and Selection Section 1 – FAST Diagram The complete system design with its logical components is more easily presented by utilizing the FAST diagram. The FAST diagram is able to take what could possibly be a complicated project and break it down to an easy to follow format. Having a recognizable format such as this enables the designer to best focus their efforts on what is needed in the final product. The FAST diagram developed by the team is shown below. Figure 2.1 - Fast Diagram 7 The Sensor Interface can be broken down into three main components: The Android app, the microcontroller, and the sensors which it communicates with. The Android app and microcontroller are essentially the support behind the sensors to collect, store, transfer and display data. Designing more advanced sensors was beyond the scope of this project, so the Android app and microcontroller became the areas of focus. The Sensor Interface was designed to accept a wide variety of sensors, Bluetooth, analog, digital, wired and I2C. Any of the sensors can also be connected to another Bluetooth module to allow a wide variety of wireless sensors to communicate with the central Sensor Interface microcontroller. Once the microcontroller has logged data from the microcontroller, it stores the data via a microSD card. Storing the data in with an onsite microSD card has several advantages, most of which that it allows for minimal power consumption by not constantly transferring the data to the Android phone. Logging data in this way allows the microcontroller to store data for weeks or months without any communication to the Android phone if desired. Once the data is wanted, simply connecting the Android phone to the microcontroller will transfer the data to the phone once the Android app is launched. From there, the phone can display the data and use it as the user sees fit. Section 2 – House of Quality The House of Quality provides excellent insight into translating what the customer wants are into what can be done. By organizing the customer’s wants by order of importance, we can effectively gauge how our design can be improved against measurable engineering field data. This methodology forces the designer to look past the obvious and really learn to put out a product that can match and exceed the customers’ expectations. The House of Quality completed for the team is shown below. 8 Figure 2.2 - House of Quality Section 3 – Budget The team was provided with the standard budget of $500 for the ECE 480 design class. As shown in the information below, the team used $450.77 out of $500 to construct the prototype. Although it was a higher cost than initially expected, several designs were tried to best implement what the sponsors requested, thus several microcontrollers were ordered. Beyond this, a few items for display purposes were donated by team members and our sponsors. All the 9 software chosen for design was open-sourced or free. The budget summary table and pie chart of purchased expenditures is shown below: Software: Hardware: EAGLE PCB Design $0 Donated: $180 $0 Purchased: $290.38 Eclipse Android IDE Sensors: Microcontroller Fabrication: Donated: 2.68 Parts Cost: $34.82 Purchased: 84.93 Fabrication Cost: $0 Logistics: Shipping and Handling $40.64 Donated Total: $217.50 Purchased Total: $450.77 Table 2.1 - Budget Summary 10 Figure 2.3 - Purchased Product Expenditures If the unit was to be made in full production, the cost in parts for each unit in quantities of ten thousand would be $20.83. The cost of manufacturing the board would be $0.54 when using the company 4PCB. The cost of assembly would be about $5 for each board using Advanced Circuits. Thus, the total per unit cost of each microcontroller would be $26.37. The breakdown of the microcontroller costs are shown below. BLE Module 4.0 10.15 Capacitors 0.066 microSD Socket 0.502 Resistors 0.138 USB Mini 0.8 LEDs 0.218 8-Bit 32KB MCU 1.77 Schottky Diode 0.042 USB to Serial UART IC 2.05 Voltage Regulator Parts 0.208 Crystal 16MHz 0.173 Coin Cell Battery 3V 4.32 PCB Board Manufacture 0.54 PCB Board Assembly 5 Full Production Cost $26.366/Unit Table 2.2 - Final Production Costs 11 Figure 2.4 - Final Production Expenditures Section 4 – GANTT Chart This project was ambitious, and it was determined part way through the semester that others would most likely follow the work done by the team at a later date. In order for the microcontroller to fit inside the size requirements of 1” by 1” by .05”, facilities outside MSU needed to be utilized in order to properly draw small lines on the PCB and add more than two layers. Lead times for getting the PCB board manufactured with parts assembled could be as long as a month, so it was decided to make a two layer board with a larger layout for testing purposes with the facilities at MSU. The software side of our project has been for the most part successful, but the hardware side fell short due to the high learning curve and the resources available. Due to this, the team is still in the chip design/testing phase of the project. Another group next semester should be able to start from where the team left off and build a tested microcontroller to interface with the software developed by the team. 12 Figure 2.5 - Initial GANTT Chart Part A 13 Figure 2.6 - Initial GANTT Chart Part B 14 Chapter 3 – Technical Work Performed Section 1 – Hardware Design Efforts The Sensor Interface’s hardware requirements include a microcontroller, a Bluetooth module, an SD card module, and a battery. The microcontroller is responsible for collecting connected sensor readings, altering sensor parameters, and transferring sensor readings to the other hardware components when necessary. It must be able to read both analog sensors and digital I2C sensors. The SD card module’s role is to provide a large memory space to store sensor readings over long periods of time, our minimum requirement was set at one hour. This module should both write to an SD card and read from an SD card when required. The Bluetooth module is needed to communicate with the Android device. It receives commands from the Android device and sends them to the microcontroller so that it can perform the correct task. The Bluetooth module also transmits sensor readings back to the Android device. These modules can all be purchased separately and connected with wires together in order to implement a design where all of this functionality is joined; however having separate modules would be clunky and inconvenient for travel. The team’s proposed solution was to design a microcontroller that included all of these parts on one board so that it can remain small and efficient in design. In order to create a customized microcontroller first a list was created containing every component the microcontroller would need on the board, first using through hole components in order to create a prototype design (see Table 3.1.1) and then using SMT package components in order to be prepared for future advances. The microcontroller board that was designed houses a micro USB port, a BLE module, a coin cell battery, and a microSD card shield along with the standard components necessary for a chip to control the incoming and outgoing data. Designing this product in the Eagle software takes careful planning and time to continually adjust where traces through the board will be routed. Eagle contains a large number of components in premade libraries. These built-in parts covered nearly everything needed to add to the design, however some of the more specific components had to be added to the design manually. The BLE module, coin cell shield, and micro SD shield were the only three parts not already included in the libraries. To get these designs to populate in the same space as the rest of the board the 15 eagle files needed to be imported from manufacturer websites which required use of the professional version of the software. These are imported as separate schematics but can be edited simultaneously with the main schematic and attached by using labels instead of wires to join the different ports. Even with separate schematics the physical layouts are represented in the same board layout page. Once all of the components are populated into the board they needed to be manually arranged in the board space we allocated, this was 3” by 3” for the original prototype. In order to fit all of the components in the through hole style careful arrangement of parts was needed on both the top and bottom of the board, this proved to be a challenge when routing traces as the bottom is typically reserved for routing only. Routing traces can begin by using the auto-route function built into Eagle. This however will not make every connection necessary for the board to function if it cannot find an easy path from point A to B. With the remaining connection a path must be manually connected along with vias to connect the ports from the different components. This task should be done with utmost care as this is where errors are most likely to be made during this process for instance errors we discovered after our board had been manufactured were that some of the traces were drawn too close together and the machinery that was available to the team could not cut the copper with enough precision, this led to several pads being treated as one which shorted many connections. Using higher precision equipment could have solved this problem which would have required the team to send the design to an outside source to be manufactured which would require time and money that was unavailable at this point in the design process. This problem would have also been avoided if the SMT package components were being used instead of the larger through-hole versions. This would have saved valuable space which could have been used for routing. The schematic designs and board layout (pictured in Appendix III figures 3.1.1-3.1.6) that were manufactured are not able to replace the Arduino board for the team at this point in time, however reprocessing these until they are fully functional is the next logical step in creating a product such as this for the market. This would lower the cost and raise the utility and convenience for the product. Section 2 – Hardware Implementation The microcontroller used is an Arduino Uno, shown in Figure 3.1. This is a popular microcontroller that is easy to wire and program. It has sufficient analog input ports to read from 16 various analog sensors simultaneously, and also features a Serial Data (SDA) line and a Serial Clock (SCL) line. Both an SDA line and an SCL line are required to support I2C sensors. With these input ports, the Arduino Uno is able to read from three different analog sensors and two digital sensors simultaneously. Furthermore, the Arduino Uno includes Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) functionality, which allows it to interface with certain peripheral hardware devices, such as SD card modules. On top of this, the board also allows digital ports to be configured to act as Serial Receive (RX) or Serial Transmit (TX) lines. These are necessary to connect with a Bluetooth module correctly. Finally, because of its popularity, many hardware modules are designed to work specifically with Arduino microcontrollers, including those that the Sensor Interface requires, like Bluetooth modules and SD card modules. Figure 3.1 - Arduino Uno The Bluetooth module used is the Sunkee HC-05 Bluetooth Module, shown in Figure 3.2. This module is cheap, readily available, and quick to acquire. It is also designed to ensure compatibility with Arduino microcontrollers. Furthermore, it is highly customizable, such as allowing its name to be changed, modifying its access password, and switching from master mode to slave mode. This last feature is important because it will enable future development of the Sensor Interface to add wireless Bluetooth sensor reading functionality. To communicate with Bluetooth sensors, the module should be in Master mode. However, when communicating with the Android device, the module should be in Slave mode. This Bluetooth module’s ability to switch between these 2 modes will allow the Sensor Interface to communicate with Bluetooth sensors as wired sensors. 17 Figure 3.2 - Sunkee HC-05 Bluetooth Module Figure 3.3 depicts the connections between the Bluetooth module and the microcontroller. The module has both a 5.0V input pin and a 3.3V input pin. Although the module may operate correctly with only one of these supply pins connected, both are connected to the microcontroller’s output voltage pins to guarantee proper functionality. The Bluetooth module’s RX pin must connect with the microcontroller’s TX pin, and its TX pin must connect to the microcontroller’s RX pin. The Arduino Uno’s default TX serial pin is P1 and the default RX pin is P0. However, these were not used for a couple of reasons. Most importantly, when P1 and P0 were used as TX and RX pins, the Bluetooth module would not communicate with the microcontroller. This meant that different pins had to be used. Fortunately, an Arduino library exists to change digital pins to RX/TX pins, called SoftwareSerial. Using this library, P3 was changed to a TX pin and P2 was changed to an RX pin. This decision has the added benefit of freeing up P1 and P0. This is beneficial because the Arduino has a useful debugging and monitoring feature called Serial Monitor. Using this, the Arduino can write messages to a computer screen when connected to a computer. However, this feature only works when P1 and P0 are not in use. Therefore, by using P3 and P2 for TX and RX instead of P1 and P0, testing and debugging was a much easier and faster process. The Bluetooth module has one more input pin, labeled KEY. This pin is used for changing its mode between Master mode and Slave mode, as well as customizing its other 18 properties. These options are not used currently, but they may be in the future. Therefore, this pin is connected to P4 on the Arduino Uno if property changes are ever desired. Figure 3.3 - Microcontroller - Bluetooth Module Connectivity The Bluetooth module used is the Kootek SD Card Module, shown in Figure 3.4. This is an inexpensive component that was designed to function correctly when connected to Arduino products. It supports both SD card reads and writes. Figure 3.4 - Kootek SD Card Module The connections between the SD card module and the microcontroller can be seen in Figure 3.5. The SD card requires both a 5V and a 3.3V supply to consistently operate correctly. During testing, only the 5V pin was connected, which resulted in correct SD accesses only every other time. This problem was corrected by connecting the 3.3V pin to the microcontroller’s 3.3V output as well. 19 The SD card module requires connections to the microcontroller’s SPI pins. These are the Arduino’s P11, P12, and P13. P11 is the Arduino’s Master In Slave Out (MISO) pin, P12 is its Serial Clock (SCK) pin, and P13 is its Master Out Slave In (MOSI) pin. These connect to the SD card module’s corresponding pins. Furthermore, The SD card module needs a connection for Chip Select (CS), which tells it whether or not it can communicate with the microcontroller. The default pin for this on the Arduino Uno is P10. Figure 3.5 - Microcontroller - SD Card Module Connectivity Section 3 – Software Design Requirements The software design of the Sensor Interface is composed of 2 major components: the code describing the microcontroller program and the code describing the Android application. The microcontroller code is responsible for managing the sensors that are connected to it, as well as their readings. Determining which sensor ports to read from, how fast to read from them, when to store sensor readings to the SD card, and when to transmit sensor readings to the Android device is all defined in this code. The Android application’s role is to act as the user interface for the user. It should display information about all of the sensors connected to the microcontroller, as well as allow the user to add sensors to monitor, delete sensors, and change sensor properties. Section 4 – Software Implementation 20 Subsection 1 – Microcontroller Program The primary role of the program on the microcontroller is to manage and monitor sensors, so a data structure called Sensor is defined. Table 3.1 shows the elements that make up a Sensor data structure. The microcontroller can monitor a maximum of five sensors, which consist of three analog sensors and two digital sensors. These sensors are kept track of in a 5element array called mSensors. The first three elements are for analog sensors and the last two elements are for digital sensors. The number representing index of the mSensors array will be referred to as that corresponding sensor’s ID. Name Type Description mPort int Which physical port this sensor is connected to (0-4) mValues[10] int Array of readings from this sensor. mIndex int Current location in the values array mLastSampleTime long Most recent time a reading was taken from this sensor mSampleRate float Number of times a second that a sensor reading should occur mEnabled boolean Whether or not reading for this sensor should take place Table 3.1 - Sensor data structure Arduino microcontrollers require two functions to be defined in their code: setup() and loop(). When the Arduino runs its program, it runs setup() first, and only once. Afterwards, it runs loop() repeatedly. The setup() function is useful for initializations, so the five sensors have their data elements initialized. The three analog sensors correlate to analog ports A0, A1, and A2 on the Arduino Uno, so these values are assigned to the mPort element for mSensors[0], mSensors[1], and mSensors[2], respectively. Digital I2C sensors all connect to the two analog pins A4 and A5, and the way to differentiate between them is their component address. The program stores this address value in the mPort element for mSensors[3] and mSensors[4]. 21 The other data elements for all five sensors are initialized identically: mIndex is set to -1, mLastSampleTime is set to millis(), mSampleRate is set to 1, and mEnabled is set to false. The function millis() returns the amount of time that the program has been running in milliseconds. By initializing mLastSampleTime to millis(), it effectively sets it to the current time. There are a few other initializations that also take place in setup(). There are a number of communication channels that must be set up. These are the serial channel to the Bluetooth module, the communication channel to the SD card module, and the I2C channel to the digital sensors. On top of these, a serial channel to the computer is useful to have for debugging purposes. The Bluetooth and computer serial channels are initialized at a 9600 baud rate. Finally, since the SD library is being used, the Arduino’s hardware Slave Select (SS) pin must be set as an output for SD communication to function correctly. This is pin 10 on the Arduino Uno. The loop() function accomplishes two tasks: sampling connected sensors at the correct time and receiving commands from the Android device and performing them. For reading the sensors, the following process takes place for each of the five sensors. First, the program checks if the sensor’s mEnabled element is set to true. If so, then the program checks if the time elapsed (in milliseconds) between mLastSampleTime and the current time (using millis()) is greater than 1000 / mSampleRate, the sample period in milliseconds. If this is true, then the microcontroller should sample the sensor and retrieve a reading. However, a number of things happen prior to the reading. First, the sensor’s mLastSampleTime element is set to the current time, using millis(). Then, the sensor’s mIndex element is incremented by 1. If the mIndex value at this point equals 10 then this signifies that the sensor’s mValues array is full. When this occurs, the microcontroller writes the entire contents of this sensor’s mValues array to the SD card. The microcontroller orders the SD card module to open a file named the sensor’s ID, appended by “.txt”. For example, if sensor[2] is having its values written to the SD card, the SD card module would open file “2.txt”. Then, all 10 sensor readings in the mValues array are written to the file, one line for each reading. The last step in this process is to set the sensor’s mIndex element back to 0. Now, the microcontroller can retrieve a sensor reading. Depending on whether the sensor is analog, or digital, the process differs slightly. For analog sensors, the microcontroller performs an analogRead() on the sensor’s mPort, and assigns the resulting value to the sensor’s mValues array at the current mIndex value. For digital sensors, the microcontroller performs 22 requestFrom() operation on the sensor’s address, which is stored in its mPort element. Then, the microcontroller reads two values, which are the most significant byte (MSB) and least significant byte (LSB) of the reading. To combine these two separate bytes into one data type, the MSB is shifted left by 8 bits, using OR logic with the LSB, and then assigned to an integer variable. I2C sensors return values of varying numbers of bits, so this new value should finally be shifted right accordingly. For example, if the I2C sensor that was read returns 12-bit values, then the combined integer value (16 bits) should be shifted right by 4 bits. This final value is then stored in the sensor’s mValues array at the sensor’s current mIndex value. Besides taking sensor readings, the program also receives commands from the Android device. These commands are in the form of character codes, depicted in Table 3.2. If a code has a [#], this means that a number follows the character. To receive these codes, the program checks if there is any data in the Bluetooth module’s input serial buffer. If there is, then the Android sent a command. The microcontroller reads this character and determines what to do. Char Code Command Description +[#] Add Begin reading sensor[#] -[#] Delete Stop reading sensor[#], delete all data for sensor [#] E[#] Enable Continue reading sensor[#] D[#] Disable Stop reading sensor[#] / Purge Delete all stored sensor data * Sync Transmit all stored sensor readings to the Android device S[#][#2][#3] Sample Rate Change sample rate of sensor[#] to [#3] ([#3] is length [#2]) Table 3.2 - Character codes received from Android device If the character read is “+” or “E”, then the same operation occurs. The program waits until another value is in the Bluetooth input buffer and reads it. This is the ID of the sensor in the mSensors array to enable. The microcontroller sets this sensor’s mEnabled element to true. A 23 similar process occurs if “D” is received, except the program sets the sensor’s mEnabled element to false. If the microcontroller receives a “-” character, it will also set the sensor’s mEnabled element to false, but it will also delete the sensor’s corresponding file on the SD card and reset all of its elements to their default values. This includes setting the sensor’s mIndex back to -1 and setting its mSampleRate to 1. In the case of a received “/” character, the microcontroller orders the SD card module to delete all stored senor files on the SD card. If the microcontroller receives a “S”, then it obtains the sensor mIndex like in the previously-mentioned cases. However, receiving the mSampleRate from the input buffer value is more involved. The program waits until another value is in the input buffer. This value represents the number of bytes that constitutes the incoming mSampleRate. The microcontroller waits until this many bytes are in the input buffer, reads them into a character array, and converts this array into a float value which is then set as the new mSampleRate for the specified sensor. Figure 3.6 gives a visual representation of the byte format for setting sensor[2]’s mSampleRate element to 2.25. Figure 3.6 - Byte format for “S” command If the received character is “*”, then the microcontroller opens each sensor file on the SD card. For every value in every file, the program writes the sensor’s ID followed by a “#” character to the Bluetooth serial output buffer, then writes the stored value in the file, followed by a “$”. This way, the Android device can discern which sensor corresponds to the incoming values in its Bluetooth input buffer. Figure 3.7 provides an example of this format if mSensors[1] had stored a value of 512 and sent this data to the output buffer. After all of the files are read and the values written to the output buffer, they are deleted. Finally, the program goes through each sensor’s mValues array up to the current mIndex and writes these values to the output buffer in the same fashion described previously. 24 Figure 3.7 - Output buffer format for sensor data transfer Subsection 2 – Android Application The Android application is responsible for two main tasks: to act as a user interface that displays sensor information and to communicate with the microcontroller regarding sensor configuration and readings. The communication protocol used to interface with the microcontroller is Bluetooth. Fortunately, the Android API includes a Bluetooth library that simplifies this communication. Before the program is run, there are a few requirements that must be met for the application to run correctly. First, the Android device must support Bluetooth communication. Also, the Arduino must be powered on and be within range of the Android’s Bluetooth module. Furthermore, the Android and the Bluetooth module connected to the Arduino must be paired before the program is run. This can usually be accomplished within the Android’s Bluetooth settings. The pin number needed to pair with the Bluetooth module is 1234. As a precaution, all other Bluetooth devices should also be unpaired from the Android, so that the only device bonded to it is the Arduino’s Bluetooth module. When the Android application is first run, one of its first operations is to establish a connection between it and the microcontroller’s Bluetooth module. To do this the following steps are done: First, the application determines if Bluetooth is enabled on the Android device. If it is not, then the program enables Bluetooth. Then, the application stores all of the devices that are currently bonded with the Android in a Set data type. It chooses the last device in this Set as the Bluetooth device that it will connect with. This is why it is necessary to pair the Arduino’s Bluetooth module with the Android before running the program, as well as why all other pair devices should be unpaired. 25 The process to actually connect to a Bluetooth device can be time-consuming and may stall the program. For this reason, the steps to form the connection take place in a separate thread, called ConnectThread. This thread’s constructor accepts the Bluetooth device that the Android is connecting to as a parameter. Using this device, the program creates a socket that will be used for communication. Afterwards, the Android and the Arduino’s Bluetooth module are connected through this socket. This is the lengthy process that can stall the program. When this is finished both devices are connected to each other and can communicate. However, this interaction can also block the program, so it takes place in a separate thread, called ConnectedThread. ConnectedThread accepts the socket used for connection as a parameter for its constructor. With it, the program obtains the Android’s input stream and the output stream for Bluetooth communication. When the Android want to send data to the Arduino, it can write to the output stream. Similarly, the Android will receive data from the microcontroller via the input stream. Writing to the output stream is straightforward. The application first converts the data that it want to transmit into a string. Then, this string is converted into a byte array, and this byte array is written to the output buffer. Reading from the input stream is more complicated. This is because many bytes of data can arrive in the input stream between stream readings, but not necessarily all of the bytes in the message. This is why the terminating characters “#” and “$” are used to signify sensor IDs and sensor readings from the Arduino. See Figure 3.7 for an example of this. When data is read in the input stream, it is added to a buffer. After this happens, the buffer is iterated through, beginning at the location after the last terminating character was found, either a “#” or a “$” (this may have happened before this input stream reading). If another terminating character is found, the program “handles” the data between the previously-found terminating character and this newlyfound character. Depending on the newly-found character, the program will handle the data as either a sensor ID or a sensor reading. This process continues until the end of the buffer. If the last character in the buffer is a terminating character, the buffer is subsequently cleared. When the program obtains the data between two terminating characters, it is often desired to use it in the UI thread. In order to send data from a separate thread to the UI thread, a Handler must be used. If the data obtained is a sensor ID, the Handler stores the ID as an integer value. If 26 the data is a sensor reading, the Handler converts the data into an integer and updates the sensor object that has the same ID as the one previously stored with the sensor reading that was just received. Besides communicating with the microcontroller, the Android application’s other crucial role is to provide a clear and easy-to-use UI for the user. The most important data to display is information about the monitored sensors. These sensors are defined in a class called Sensor. Table 3.3 lists the attributes of the Sensor class. The sensor objects being monitored by the program are stored in a container class called SensorPack. Name Type Description mId UUID Unique identifier used to find this specific sensor mName String Displayed name of the sensor mValues ArrayList<Double> All of the sensor’s readings mPort int Correlates with the ID number of the Arduino sensor object mSampleRate double Number of sensor readings per second mEnabled boolean Whether or not the sensor readings are being stored mRawMin int Minimum sensor reading value mRawMax int Maximum sensor reading value mConvMin double Minimum displayed sensor value mConvmax double Maximum displayed sensor value Table 3.3 - Sensor class attributes There are two main screens that make up the user interface, and one minor screen. One of the main screens is the list of sensors that the microcontroller is currently monitoring. The list consists of sensors in the SensorPack object. For each sensor in the list, the UI displays that 27 sensor’s name, port number, most recent sensor reading, and whether it is enabled or not. Figure 3.8 shows this list with four monitored sensors, three of which are currently enabled. Figure 3.8 - List of currently-monitored sensors Besides the the list of sensors, this screen has three other elements: the buttons in the topright corner. The leftmost button is the Purge button. When this is pressed, the Android device writes “/” to the Bluetooth output buffer. The button to the right is the Sync button. When pressed, the Android writes “*” to the output buffer. The last button is the Add Sensor button. When pressed, a new Sensor object with default values is created and added to the SensorPack 28 container. Then, the screen switches to the Sensor Properties screen, which displays the new sensor’s attributes. This screen will be described in more detail later. There are a couple other features in this list view. First, by pushing on one of the sensors in the list, the Sensor Properties screen appears displaying the selected sensor’s attributes. Also, by click-and-holding a sensor in the list, the user is given the option to delete it. If the user chooses to do so, the sensor is removed from the list, deleted from the SensorPack, and the Android sends “-[#]” to the output buffer, were [#] is the sensor’s port value (which corresponds to the Arduino sensor object’s ID value). When either the New Sensor button is pressed, or when a sensor in the list is pushed, a new screen appears that displays properties about the sensor. Figure 3.9 shows what this screen may look like. The text fields are automatically populated with the element values of the sensor. From this screen, the user can change the sensor’s attributes. 29 Figure 3.9 - Sensor properties The Sensor Properties screen has a few interesting qualities. If a port is already being used by another sensor in the SensorPack, then that port is unavailable for selection. Also, the Sensor Interface has a maximum sample rate of 20 samples per second. If the user enters a value higher than this in the Sample Rate field, it is automatically changed to 20. The Sensor Interface also has a minimum sample rate of 0.1, so the same process occurs if the user enters a value lower than this. Finally, for the converted sample rate values, if the user enters “.”, an error can occur since “.” is not a valid double value. Therefore, in this case, the application changes the input to “0.”, which is a valid double. 30 There is a button in the top-right corner of the screen. If the user presses this button, they will see all of the values in the sensor’s mValues array. Figure 3.10 gives an example of this screen. Figure 3.10 - Sensor readings When the user is finished viewing and modifying the sensor’s properties, they can press the Back button in the top-left corner of the screen. This button will bring the user back to the list of sensors and update each Value text field in the list with the last value in each sensor’s mValues 31 array. Also, if any changes were made to the sensor’s sample rate or port value, this information is sent to the output buffer. In the case of a port change, the application write “-[#1]”, followed by “+[#2]” to the output buffer. [#1] is the previous port value and [#2] is the new port value. If the enabled checkbox changed, the program writes either “E[#]” (for enabled) or “D[#]” (for disabled) to the output buffer, where [#] is the sensor’s mPort value. In the case of a sample rate change, the program writes “S[#1][#2][#3]”, where [#1] is the sensor’s mPort value, [#3] is the sensor’s new mSampleRate value, and [#2] is the length of [#3]. If the Android application ever receives input from the Arduino, it will process the incoming data and pull a port number and a sensor reading from it, and call a function to store the value in the corresponding Sensor’s mValues array. To do this, the program utilizes the sensor’s mRawMin, mRawMax, mConvMin, and mConvMax attributes. The raw values represent the range of values that the incoming sensor reading could be. Typically for analog sensors, this range is from 0 to 1023 because the Arduino’s analogRead() return a value in this range corresponding to a voltage reading between 0 and 5. For example, a reading of 0V returns 0, 5V returns 1023, and 2.5V returns 512. However, this value may not be useful to the user. They may want to see the data between a different range of values. This is what the conv values represent. The program scales the input sensor reading to the appropriate value within the range specified by mConvMin and mConvMax. For example, if these two attributes are set to 0 and 100 respectfully, and the sensor reading is 512, the sensor adds a value of 50 into its mValues array and updates the corresponding text field in the sensor list. Chapter 4 – Testing Section 1 – Hardware Testing The ability to test the capability of the hardware and software was important to the results of the project. Being able to test the hardware however is a difficult task as many of the tests of the hardware and software are a binary result, either it works or it doesn’t work. This makes the real test data for the team, the reliability of the different components being used. 32 Creating a reliable product that will consistently work as desired is an obstacle of designing a product from scratch. In order to accomplish this goal, thorough research had to be done for separate portions of the products. The most popular modules were used due to their affordability and accuracy/reliability for the price. One such module that was ordered was for the project was the HC-05 Bluetooth 2.0 module to allow for Bluetooth communication with the a phone as mentioned above. The main test that was able to be done with the Bluetooth module was the speed of communication that could reliably be used. Communication with this module is done through the serial lines which is measured in units called Baud (Bd) or bits/sec. The module has several settings for the available supported baud rates from 9,600 Bd to up to 460,800 Bd. While the maximal speed available to the device is ideal, other limitations come into play. The availability of serial communication lines on the ATMega328P chip is limited and caused the team to require the Software Serial Arduino Library. This library has been tested reliably up to 115,200 Bd and is as now the upper limit imposed upon the serial communication with the Bluetooth module. The HC-05 Bluetooth module has a secondary programming mode that allows for communications to be tested with the module itself. The baud rate of the chip was varied between the available baud settings to test the ability to communicate directly with the module. As there were only select number of rates that could be set (9,600; 19,200; 38,400; 57,600; 115,200) the highest available (115,200) was chosen for optimal communication speed. Testing in at 115,200 caused the microcontroller to not reliably receive a signal from the HC-05 Bluetooth module and so the rate was reduced until a fully functioning baud rate was found. In the end, 38,400 Bd allowed very solid results when communicating with the module and so became the set rate. Research on different forums discussing the HC-05 supported this conclusion stating that while the manual of the chip states supported rates of up to 460,800 Bd, the chip only functioned with rates less than 57,600 Bd. Section 2 – Software Testing Software testing included more testing of reliability and after reaching certain points in the project began to have constant working expectations, meaning that the developed software would always work after the initial testing had been finished. There were two different pieces of 33 software to be tested and so each had to be subjected to different requirements and tests. These software aspects were the Android code to be developed and Arduino microcontroller code that controlled the data flow of the sensors. Android programming for the phone application is destined to contain flaws as the amount of programming required to create a deployable application is extremely large. To simplify the end goal, the application was tested only under a user correctly navigating through menus as well as starting device use in a specific order (Powering on the microcontroller and then starting the phone application). Each successive feature added to the application needed to be used under various conditions to find flaws in logic that could cause the application to crash or not function as intended. Since the application built in Android was based on tutorials for building basic Android applications, the original menu navigation pieces that were built on functioned as expected. Starting at the home menu that is seen when the application boots up, pressing the plus symbol in the upper right, overlays (shows) a new window with the current options for adding the sensors. This is true for all other screens that appear when navigating menus. Appearance and disappearance of the menus in a smooth manner without the application crashing or freezing shows that the code for displaying the menu goes through the correct channels. Multiple button presses to show/hide the menu showed that this simple visual process was fully functional. When adding and removing sensors in the interface, many issues could arise in the application. Once added, the home screen needed to display the information of the added sensor. A simple check of whether the information displayed is correct after addition corresponds to a functioning sensor addition. The same case is true for removal of a sensor. After a sensor is removed from the list of currently reading sensors, the information should no longer be displayed on the home screen since stored information for the sensor is not necessary. Adding and removing sensors was an iterative process for code development adding features such as: enabling/disabling so that it can be activated/deactivated but data isn’t deleted; modifying the conversion factor for a sensor so that the data displayed on the phone is meaningful; changing the sampling rate to sample more/less often. As stated earlier, there are going to be flaws/bugs in the Android application that don’t currently behave as expected. One such error that has been found is when the screen tries to rotate to a landscape view. Any data that has been displayed when the screen is in being viewed 34 in portrait is no longer displayed. The current cause of this easily found issue has to do with the code for viewing the screens themselves but is currently not known and is something to be looked into in future work. Moreover, not powering up the microcontroller before starting the Android application causes the application to crash when trying to change any settings that require communication with the microcontroller. Crashing happens due to the lack of a bluetooth device being connected to the phone. A number of sensors were used in testing: a potentiometer, an analog luminosity sensor, an analog humidity sensor, and a digital temperature sensor. The potentiometer and the humidity sensor both had voltage dividers built into them, so wiring the voltage divider pin of each to analog ports on the microcontroller was simple. However, the luminosity sensor only consisted of two pins and generated a resistance between them, where this resistance depended on the ambient light. Therefore, a voltage divider was created manually. First, the minimum and maximum resistances of the light sensor were measured. These values were 32Ω and 2KΩ, respectively. From these values, it was determined to put the sensor in series with a 270Ω resistor. With this configuration, when connected to a 5V source, the voltage across the sensor would be between 0.53V and 4.4V, respectively. Equation 4.1 shows these calculations. The digital temperature sensor was connected to the appropriate analog pins for I2C communication. Equation 4.1 - Min and Max Luminosity Sensor Voltage Drops The microcontroller was connected to a computer during testing. This way, the Arduino’s Serial Monitor could be used to debug the microcontroller program and locate and fix errors. The program was written such that when a sensor was read, it would write the sensor’s ID number followed by the reading to the Serial Monitor. Also, whenever the Arduino received a command character from the Android device, it would write this character to the Serial Monitor as well. This allowed for verification that the Bluetooth communication worked as intended and that the microcontroller performed the correct action for the given command. 35 The Bluetooth module wired to the microcontroller has an LED which flashes in two patterns: a disconnected pattern and a connected pattern. After opening the Android application, monitoring this flash pattern was one of the first diagnostic tests used. If the pattern did not change to the connected pattern, than there was an error that needed to be found and fixed. Otherwise, the Android connected to the Arduino’s Bluetooth module successfully. When the Android application is first run, the sensor list should be empty, since no sensors were added yet. Pressing the Purge or Sync button should send “/” or “*” to the Arduino, which should print the character to the Serial Monitor. However, nothing else should happen since no sensors are added to be synced and no data exists to be purged. From here, testing consisted of adding multiple sensors to be monitored simultaneously, changing their sample rates and seeing the result in the Serial Monitor, and enabling, disabling, syncing, and deleting sensors to verify that the programs on both the microcontroller and the Android device functioned correctly. Chapter 5 – Conclusion Section 1 - Final Prototype During the course of the semester, a successful prototype for the Sensor Technology Interface, as well as designs for both the final printed circuit board and the server-side supported backend library, has been completed. The prototype consisted of devices running versions 4.1.2 and 4.2 of the Android mobile operating system, the Arduino Uno microcontroller, as well as various sensors. A wide range of sensors were tested, including analog and digital sensors both wired and wireless, as well as sensors using different protocols. However, the final prototype will showcase a digital temperature and humidity sensor, as well as analog light and water level sensors, as well as a potentiometer to sense angle. Section 2 - Cost Subsection 1 - Prototype Cost 36 The project cost consisted of donated hardware, purchased hardware and software, and donated time for microcontroller fabrication. The total donated amount totals $217.50, and the total purchase amount totals $450.77. This cost includes sensors and microcontrollers not used in the final prototype, such as the SensorTag and the RFduino. Although it was a higher cost than initially expected, several designs were tried to best implement what the sponsors requested, thus several microcontrollers were ordered. All of the microcontrollers can still be used to create more advanced wireless and/or wireless sensors. Subsection 2 - Production Cost The projected cost will be $26.36, if bought in units of ten thousand. This costs includes the manufacturing of the printed circuit board, $0.54; the price of the individual parts, $20.84; and the price of assembly, $5. Although this final production cost is slightly over the target production cost of $20, if the USB module and the battery are sold separately, the overall cost will fall below the target cost of $20/unit. The BLE Bluetooth module is also relatively new, and should be expected to lower in price as more products adopt the standard. Section 3 - Schedule This project was ambitious, and it was determined part way through the semester that others would most likely follow the work done by the team at a later date. Lead times for getting the PCB board manufactured with parts assembled could be as long as a month, so it was decided to make a two layer board with a larger layout for testing purposes with the facilities at MSU. The software side of our project has been for the most part successful, but the hardware side falls short due to the high learning curve on building a microcontroller from scratch and the resources available at MSU. Due to this, the team is still in the chip design/testing phase of the project. Another group next semester should be able to start from where the team left off and build a tested microcontroller to interface with the software developed by the team. Section 4 - Findings The final prototype consists of a final tested sample rate of 20 samples/second for each 37 sensor. It also includes a variable size SD card that can provide more than 1 hour of buffered input. The required dimensions were not accomplished with our through hole design. However, with a DIP design, it will reach the desired sample size. Furthermore, the application allows the user to clear the buffer, enable and disable sensors, as well as allow the user to specify a conversion factor. The sensors working with our interface allows for I2C digital sensors, and analog sensors. All sensors use the analog input pins. Furthermore, the device can run on a battery. The sponsor has since replaced the TRRS communication requirement with Bluetooth. The timestamps also work, as well as the library backend, however they have not been fully integrated into the interface due to an early miscommunication of writing the library in C instead of java, and that there is currently no way to pull files from the microcontroller itself. Section 5 - Future Work Currently, the project lacks a full integrated backend to make it function out of the box without preconfiguration. The Android application itself requires more development/testing to ensure that the end user can intuitively and without fail use the interface. To achieve the out of box performance, the process of being able to connect to any sensor interface device without large amounts user interaction is required, meaning configuring and saving Bluetooth connection to a Sensor Interface device. Once data can be reliably sent to and logged on the phone, the ability to view data graphically can be implemented. Furthermore, the timestamp needs to be integrated into the system as well for being able to know the date and time of the data recorded. In terms of the microcontroller software, more sensors should be tested to show true compatibility, and Bluetooth 4.0 needs to be fully implemented for lower power consumption, updating from the use of the current HC-05 Bluetooth 2.0 module. Code for the microcontroller should be reviewed/revised to achieve optimal performance and utilize the available resources as best as possible. Additions to the microcontroller for entering separate modes such as sleep, configuration, and communication modes need to be programmed in. A sensor application protocol should be further developed for communicating the sensor data necessary identifying processing the sensor data for easier use. Switching to the Sensor Interface hardware, the printed circuit board should be redesigned to use the surface components necessary in order to produce at the minimal size possible. Without a fully developed printed circuit board, power consumption of the device could 38 not be measured which is necessary to decide on the battery that would be required. Lack of a printed circuit board with surface mount components also makes knowing the optimized board size difficult. Though it’s arbitrary, choosing a connection method to connect sensors to the Sensor Interface in an efficient and expandable manner needs to be developed. Other than fixing small errors that may result in the initial production phases, different wireless modules for communicating with sensors could be implemented in future versions of the product. Beyond these minor setbacks, the foundation created by the team will lead the Sensor Interface towards success. 39 Appendix 1 – Technical Roles Nick Henry - Lab Manager Over the course of the semester Nick Henry worked on several different aspects of the teams design project, including both hardware and software. To start the semester he planned on working alongside Brian Wirsing on learning Android coding and creating the user interface to control the sensors in the project. Instead of using the traditional Eclipse and java programming Nick explored with software called AppInventor 2. This software was created by MIT as alternative to learning java and it created a more intuitive coding environment. He ran through several tutorials and researched ways use a smart device’s built-in features to create a more interactive program. This research helped him to create several test apps that are shown in Figure A.1 and figure A.2 that highlighted some of AppInventors unique capabilities. Nick’s research into this program also led him to discover its incompatibility with standard java code. By using this standalone program the team would not be able to integrate existing code into the new code and so they abandoned this route of creating the Android software. Once this direction changed so did Nick’s role and he began work on the hardware design portion of the teams project. He began watching tutorials, reading, and asking knowledgeable colleagues about how to design printed circuit boards in Eagle design software. Robert Pollum and Nick created a list of components that they would need in order to achieve every aspect that they required from the sensor interface circuit, this table is shown in Table 3.1. From this list of parts he imported schematics into Eagle and arranged them onto the designed PCB area in a way to allow convenient access to the I/O devices and to allow the pin headers to be conveniently located for the input of sensors. Nick then worked on routing the traces to allow for every connection 40 required. This task unfortunately also did not get implemented into the team’s final design, they are planning on running the sensor interface project from an Arduino Uno with attached BLE, SD, and power modules instead of the designed package. This is due to the fact that the manufacturing capabilities available at MSU could not cut traces precise enough for the designed pathways and sending the design to a manufacturing facility that could design to these specs would require more time and money than they had originally allocated to this portion of the project. The final board design created by Nick is shown in Figure 3.1.1. Kelton Ho - Document Manager Kelton was a programmer throughout the semester. He started on designing a viable library to store information from many different types of sensors. He took design influences from the way the command “lsusb” command handles both vendors and device IDs in 16 bit hex. He then took a list of what information sensors will need to access in order to function properly, and added some of the basic variables needed. He also did research on external libraries, so that a custom XML parser was not needed. He did a full test of all functions with sample out included in the Appendix. When he started working on the Android portion of the project, he managed and served as technical support for git conflicts and merges. He also contributed research and knowledge on Android programming, as well as designing and prototyping functions for getting and setting valid input for sample rate. He also helped to design the sensor fragment, as well as portions of the main sensor list fragment. He also worked on debugging application crashes: first, with Bluetooth off, the application suffered a fatal crash; second, if Bluetooth was on but the phone was not paired the application still crashed; third, values entered for raw values, converted 41 values, and sample rate could not be deleted completely to enter a new one and would not take decimals. The first bug was fixed by not starting the application until Bluetooth was fully loaded. The application does assume that the microcontroller is properly paired and connected, as the second bug still exists. The final bug was fixed by buffering the input and setting a decimal into the string “0.” to be displayed back to the interface. Finally, following the implementation of communication between the android device and the microcontroller, there was sometimes a pause between sending an operator and the sending of the real data, leading to an invalid input entry. This was fixed by discarding invalid input between operators. Nick Huff - Team Manager If there’s anything that’s been learned about the design process this semester, it’s that the design process is not linear. There are several different avenues that one can take in the design process, and sometimes the best route is discovered only after another has been started. Many of the roles originally assigned had to be modified to accomplish the task at hand to keep within time constraints. Nick’s role was to work on a design of the microcontroller by applying his electrical engineering knowledge in a real world application. In order to effectively offer the sponsors the microcontroller they were looking for, it was decided that that the best course of action would be to reverse engineer an Arduino microcontroller and add the additional parts such as a microSD card slot, BLE Bluetooth 4.0 functionality, and standalone battery operation. Nick found the different Arduino board schematics online and balanced the advantages and disadvantages in each setup. He helped source the parts necessary to add onto the microcontroller to fit the sponsor's requirements. After some research, it was determined that the 42 sponsors request for a 1” by 1” by .05” microcontroller would not be possible due to the time constraints and the resources available. Nick Huff aided Nick Henry worked on the Eagle Schematic designs, and weighed the technical capabilities of facilities here at MSU against outside companies to build an effective product. At the beginning of the semester, he learned how to write Android applications using Eclipse, and wrote several sample programs to brush up and Android programming. His main focus was on the action bar for the Android app, creating the front end for the back end functionality implemented by Brian. He created the layout to add additional sensors, sync with the data gathered by the microcontroller, and delete sensors that were no longer necessary. Nick also used his hands on shop experience to complete the display for design day and used his CAD experience to make several 3D printed parts to bring additional functionality for the display board. Robert Pollum - Presentation Manager Robert’s main varied throughout the semester. He has knowledge/experience in several different areas of the project and so worked where and when help was needed or requested. Much of the work included research for different aspects of the project. The research for the beginning of the project included the platform and available specs of the different microcontrollers that could be used for the project. Microcontroller units were selected for several different aspects that were believed to be important for the project. Later research included printed circuit board design, such as finding schematics to prototype boards that were being used to allow for an easier base for the final printed circuit board design. The parts that were to be used for the board were also researched and double checked to ensure the final product would both work and have all the necessary components. 43 Later in the project, a designation for working on peripheral aspects of the microcontroller code was assigned. Code was developed and researched for adding timestamps to the files created on the required SD card. Further development and research produced the ability to use character arrays for file names, which saves the Static Read Only Memory (SRAM) from being used up by constant character arrays. Though the research and development wasn’t fully completed, code was developed to allow the HC-05 Bluetooth module to be reprogrammed and change the module from a master configuration into a slave. Being able to reprogram the module would for alternate uses for the overall project and give the module itself the ability to be very flexible. The role of presentation manager was also the assigned role for Robert in the group. Overall presentations were checked over and roughly an even amount of work was done by the individual group members. The presentation poster design was worked with and influence by both Nick Henry and Robert himself. Brian Wirsing - Webmaster Brian Wirsing was a valuable team member throughout the duration of this project. His assigned task for the project was to develop code for both the microcontroller and the Android program. The work he accomplished on the microcontroller enables it to perform many key functions that his group’s sponsors requested. For example, the code he developed allows the microcontroller to enable and disable sensor ports, indicating whether or not the sensor should read from these ports. Also, the microcontroller can modify the individual sample rates of each of these sensor ports, allowing it to read some sensors at a faster rate than other sensors. He helped make the Sensor Interface compatible with a multitude of different types of sensors, such 44 as analog and digital sensors. The microcontroller has limited integrated memory, which is not suitable for extended sensor monitoring, so Brian added the capability to store the collected sensor data in an SD card. Furthermore, the microcontroller can read from the SD card to retrieve the stored sensor data. Finally, the microcontroller has to receive its instructions from an Android device, so Brian added to ability to communicate with a Bluetooth module connected to the microcontroller. With this, the Sensor Interface receives which ports to enable and disable, what the sample rate for a given port should be, and if it should send back sensor data to the Android device. Brian also helped write the code for the Android program, which acts as a user interface to display sensor information to the user and allow the user to modify certain parameters of the Sensor Interface easily. He designed the UI to show all of the current sensors in a list, displaying each sensor’s name, port, last received value, and enabled/disabled status. He added a “Sync” button to refresh the entire sensor values with the most recent value received from the microcontroller. A sensor can be deleted from this list by press-and-holding it for a short duration and selecting “Delete.” Furthermore, Brian added the ability to add new sensors to monitor by clicking the “New” button. This opens a “Sensor Properties” window where the user can give the sensor a name, specify the port it’s connected to on the microcontroller, enter a desired sample rate, enable or disable it, and convert the value received from the microcontroller to a different value. This last point is important because analog sensors generate values between 0 and 1023. However, if the analog sensor is a temperature sensor capable of reading values from -20°C to 120°C, the user will want to see the value in terms of a temperature instead of an arbitrary 0 – 1023 scale. Brian added the necessary functionality to allow for this. Users can also edit current sensors by clicking them in the sensor list, which will open this same “Sensor Properties” window, thereby allowing them to alter the sensor parameters further. One of the most important aspects of the Sensor Interface is the wireless Bluetooth connection between the microcontroller and the Android device. Through this connection, the Android tells the microcontroller which ports to read from and how fast, while the microcontroller sends back sensor values whenever instructed. Most of this functionality resides within code on the Android side. Brian programmed the Android application such that when it is run, it enables Bluetooth on the device if it is turned off. Then, it connects to Bluetooth module wired to the microcontroller, enabling wireless communication. The Android program then 45 constantly reads the Bluetooth input stream waiting for data from the microcontroller, while writing to the output stream only when instructed to by the user’s input. 46 Appendix 2 – References [1] "RFduino - Home." RFduino - Home. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Feb. 2014. <http://www.rfduino.com/>. [2] "ArduDroid: Simple Bluetooth control for Arduino and Android - TechBitar" ArduDroid. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Feb. 2014. <http://www.techbitar.com/ardudroid-simplebluetooth-control-for-arduino-and-android.html>. [3] "Arduino - Serial." Arduino - Serial. N.p., n.d. Web. 22 Apr. 2014. <http://arduino.cc/en/reference/serial>. [4] "Arduino - SPI." Arduino - SPI. N.p., n.d. Web. 22 Apr. 2014. <http://arduino.cc/en/Reference/SPI>. [5] "Arduino - Wire." Arduino - Wire. N.p., n.d. Web. 22 Apr. 2014. <http://arduino.cc/en/reference/wire>. [6] "Bluetooth." Android Developers. N.p., n.d. Web. 22 Apr. 2014. <http://developer.android.com/guide/topics/connectivity/bluetooth.html>. Appendix 3 – Technical Attachments Price per Site Site Part Number Part Description Unit Quantity Price Total 140Mouser SEA100M1CBK0407 10 uF Electrolytic Capacitor 0.09 2 0.18 Mouser 271-10K-RC 10K Ohm Resistor 0.13 3 0.39 1K Ohm Resistor 0.06 3 0.18 660Mouser MF1/4DCT52A1001F 47 660Mouser MF1/4DCT52R6800F 680 Ohm Resistor 0.06 4 0.24 594Mouser K104M15X7RF53H5 0.1 uF Ceramic Capacitor 0.1 5 0.5 Mouser 520-HCU1600-20X 16 MHz Crystal Oscillator 0.6 2 1.2 Mouser 595-UA78M05IDCY 5V Voltage Regulator 0.64 1 0.64 Mouser 863-MBR0520LT1G 20V 500 mA Zener Diode 0.34 1 0.34 5.75 1 5.75 FTDI FT232BM USB Mouser 895-FT232BL UART IC FTDI FT232RL USB Mouser 895-FT232RL UART IC 4.5 1 4.5 Mouser 638-HLMP-1700 2.0 mm Red LED 0.46 1 0.46 Mouser 638-HLMP1790 2.0 mm Green LED 0.46 2 0.92 Mouser 638-HLMP1719 2.0 mm Yellow LED 0.49 1 0.49 Mouser 649-54102-G0803LF 3x2 Male Header 0.57 1 0.57 Mouser 556-ATMEGA328P-AU ATmega328 Chip 3.12 1 3.12 Mouser 538-54819-0519 Mini USB Connector 1.49 1 1.49 656Mouser ST11S008V4HR2000 microSD Holder 2.92 1 2.92 Mouser 603-BLE112-A BLE Module 13.95 1 13.95 CAP ALUM 10UF 35V Digi-Key PCE3947CT-ND 20% SMD 2 0.18 48 Table A3.1.1 - Component List Figure A3.1.1 - Eagle Schematic chip Figure A3.1.2 - Eagle Schematic battery 49 Figure A3.1.3 - Eagle Schematic BLE chip Figure A3.1.4 - Eagle Schematic Micro SD shield 50 Figure A3.1.5 - Eagle Board Layout Design 51 Figure A3.1.6 - Eagle Board Layout Manufactured Figure A3.1.7 - AppInventor2 Block Design Figure A3.1.8 - AppInventor2 GUI 52