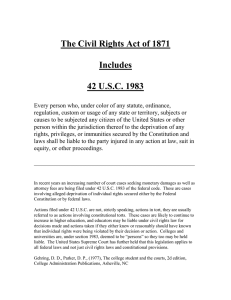

TITLE VII of the CRA of 1991 Text: “§2000(e)-(2) Unlawful Employment practices – It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an employer – (1) to fail/refuse to hire/discharge any individual or otherwise discriminate w/respect to compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges b/c of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or natural origin; or (2) to limit, segregate/classify employees/applicants in a way which would deprive any individual of employment opportunities or adversely affect his status” §2000(e)-2(k)(1)(A)“Burden of proof in disparate impact cases. An unlawful employment practice based on disparate impact is established under this subchapter only if –(i) a complaining party demonstrates that a respondent uses a particular employment practice that causes a disparate impact on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national original and the respondent fails to demonstrate that the challenged practice is job related for the position in question and consistent with business necessity.” PRIMA FACIE CASE UNDER TITLE VII **Cannot serve as a basis of a §1985(3) c.o.a.** 1. Discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. (i.e. membership in a protected class) Intentional discrimination – ex. Contractor fired females who can’t work on high beams because of fear of heights; but men with same fear were just reassigned. Disparate impact – actual intent NOT necessary. Plaintiff must move disparate impact on protected grounds, then burden shifts to defendant to show the disparate impact is necessary for effective performance (Ex. Height/weight for cops) 2. The discrimination adversely affects terms/conditions of employment Assumes liability against the EMPLOYER MEANING OF “SEX” IN TITLE VII - To the extent the term is ambiguous (could be orientation, act of sex, gender, etc.) turn to LEG HISTORY – there isn’t much here (sex was put in the Bill to get it to fail (poison pill)) - Sex = gender; male vs. female - Sexual harassment o If female members are being subjected to demands that men are not, their work conditions are altered –men and women are being treated differently based only on their sex o STANDARD = If π had been of the other sex, would the harassment have been directed at him/her? NO sex is a MOTIVATING FACTOR Does not require a large group b/c the statute reads “INDIVIDUAL” o Same theory applies to same-sex advances Ex. Elaine repeatedly subjects 2 of her female subordinates to unwelcome demands If the subordinates were men, would the harassment have occurred? NO the individual’s sex is the motivating factor Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services (pg. 790) o Facts – π worked on an oil rig and was harassed by male supervisors who threatened him w/rape and sex-related humiliations o Holding: Same-sex harassment is actionable under Title VII Distinguish b/w simple roughhousing vs. what a reasonable person would find abusive Need NOT be motivated by sexual DESIRE What if there are no women on the rig? How do you prove that π would have still been treated differently? o Pricewater House v. Hopkins – look at the identity and attributes of the sex itself (take out the female comparison); it is discrimination to impose stereotypes on workers o Ex. Not hiring a gay man b/c he does not possess masculine characteristics. Have to distinguish b/w characteristics of biological sex vs. orientation So far the S.C. has held that Title VII does NOT cover sexual orientation (Ex. firing men and women b/c they are homosexual – no Title VII violation) o Ex. Not allowing a woman to be a supervisor b/c competitiveness and assertiveness are not characteristics women “should have” o LIMITS – based on social sensibilities (i.e. we have segregated bathrooms) Equal opportunity harassment Ex. Supervisor made life miserable for male and female employees alike by repeatedly subjecting them to sexual demands o NO TITLE VII VIOLATION – Title VII has a narrow focus and only deals with DISPARATE treatment What if the harassment is nonsexual in nature but against everyone. If a supervisor is hypercritical of everyone, men and women will have different reactions o EEOC v. NEA – Same harassment directed equally may be more egregious in affecting conditions of employment when directed against a woman o Racial discrimination analogy to sexual orientation Ex. Employer prohibits interracial relationships among his employees. Looking at it from the group level, this would be “equal opportunity harassment” b/c everyone is subject to the invidious restriction Shift the focus of the analysis to the individual = VIOLATION o Ex. White woman starts dating a black man. That would be prohibited. If the man was white, there would be no prohibition of the relationship race is the motivating factor Can you argue this theory for sexual orientation? Ex. If there is a man who is attracted to a woman and is not fired, but a woman attracted to a woman is fired, the discrimination is based on that person’s SEX o Discrimination based on the sex of the individual attracted to the 3rd party not based on orientation, but status as a man or a woman and who they “should” choose as a partner 42 U.S.C. SECTION 1981 Text: §1981 (a)-(c) “(a) all persons shall have the same right in every state and territory to make and enforce contract, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, etc. (b) The term “make and enforce contracts” includes the making, performance, modification, and termination of contracts, and enjoyment of all benefits/conditions of the contractual relationship. (c) The rights protected by this section are protected against impairment by nongovernmental discrimination and impairment under color of state law” HISTORY Analytical dilemma regarding in what Amendment to find the roots of §1981 o 13th Amendment reaches private action; 1866 Act; 14th Amendment limited to state action; 1870 Act reenacted 1866 Act and §1981 13th Amendment (abolishes slavery) o Goes beyond state action o §2 gives Congress the power to reach PRIVATE discrimination – end the badges and incidents of slavery (broader power to eliminate racial discrimination) CRA of 1866 (supported by 13th Amendment) o Citizens of every race and color shall have equal rights to make and enforce CONTRACTS as enjoyed by WHITE citizens th 14 Amendment (reiterates some provisions of 1866 Act and reenacted it to make sure it has constitutional support) o Directed at STATE action o Reads “any person” rather than “citizen” Voting Rights Act of 1870 (reenacted the 1866 Act under 14th Amendment authority) 1874 – Recodification o MODERN STATUTES WITH ROOTS IN THE 1866 ACT = §1981, §1982 §1981 – ALL PERSONS (reflects the 14th Amend.) have the right to enforce and make CONTRACTS §1982 – ALL CITIZENS (reflects 1866 Act) have the right to inherit, purchase, lease, etc property Does it reach PRIVATE conduct? YES o Jones v. Alfred H Mayer Co p. 595 Begin with text – no clear language of the 14th amendment directing the duty to the states BUT it refers to rights held, and those who grant/deprive rights are state/local govts Legislative history Context of sweeping application to prevent prevailing public sentiment against freed slaves Compare to criminal sections which are clearer on their application to government But if we look at the statements made on the floor, you can always invoke either side! REQUIREMENTS 1. Discriminatory refusal of contract rights (by state or private party) – triggered at the MAKING of the contract (and extends to enforcing and performance (added in (b)) 2. Discrimination because of race 3. Intent to discriminate (unlike Title VII which allows disparate impact) 4. Possibility of respondeat superior (open question – the party with whom you contract is not always the party denying you equal rights) 5. Limited by 1st Amendment values To the extent someone applies §1981 to a contractual relationship that may have a core 1st Amendment value like advancing political views, the intimate group ought not be regulated (freedom of association) §1981 reaches PRIVATE action Because Jones was decided, the Court is really tied to stare decisis and the influence of Jones’ interpretation of the history o If §1982 reaches private discrimination, and both §1981 and §1982 arose out of the 1866 Act (13th amend statute), then the same analysis ought to apply to §1981 (even if the subsequent analysis is different) o Concurrences (Powell/Stevens) think that either Jones should not be followed here or that Jones was wrongly decided; dissent (White) thinks that the different legislative histories b/w §1981 and §1982 prevents their similar interpretation MODERN provision (c) complies with Runyon: all rights protected are protected against impairment by NONGVNT discrimination AND under color of state law o (But prohibiting private action that impinges on “every right” in §1981 creates a problem – some things in (a) seem to be directed at gvnt – Ex. If Dillard’s is subjecting customers to pain or restricting the full/equal benefit of all the laws) o Runyon v. McCrary (pg. 642) Facts – 2 Black families denied admission for their sons to private schools based on their race. Does §1981 prevent PRIVATE schools from excluding qualified children based solely on their race? Holding: Private discrimination prohibited under §1981. Since §1981 is a companion statute to §1982 and this issue was already decided in Jones, it is only a minor expansion 1. TEXT o No clear language prohibiting the state (does not say “no state shall deprive…”) BUT, the last clause imposing punishment, pains, penalties, etc. seems like it can only be directed against gvnt defs o If it was only prohibiting states from enacting discriminatory laws, how does that affect private? Under the CL, there are no restrictions on private contracts – offeree can accept or reject on any basis! If all §1981 did was prevent states from having differential laws, then a state would be in COMPLIANCE w/the CL that anyone can accept/reject contracts and everyone has that equal right (it would not prohibit private parties from discriminating) 2. HISTORY o §1981 refers to “all persons” having the same right – argument that it is more associated w/the 14th amend language §1981 only triggered at the MAKING of contracts – Requirement #1 Patterson v. McLean Credit Union p. 636 – Rehnquist wants to get away from Jones principles and reconsider Runyon o Facts – π brought §1981 claim that she was harassed on the job, refused a promotion and fired o Holding: reaffirm Runyon on stare decisis (Congress could have “overruled” it; no intervening dvlpt since suggesting Runyon was wrong; precedent is not unreliable) Before the addition of (b), §1981 did NOT cover the PERFORMANCE of contracts, which goes to the effect of harassment on the job (only making/enforcing) The promotion HERE is the FORMING OF A NEW CONTRACT Before Congress added (b) defining to include performance, Patterson left a big HOLE in the analysis o No discrimination in the performance, but there is at the making and enforcement arbitrary line-drawing Keck v. Graham Hotel – Hotel refused to host black couple’s wedding reception because of their race Denial of contract formation Congress enacts (b) to overrule Patterson: “Make and enforce contracts” = making, performance, modification, and termination of contracts, and the enjoyment of all benefits, privileges, terms and conditions of the contractual relationship Even after Congress steps in and adds (b), injury still only begins at the MAKING of the contract o Private discrimination b/w parties who have not yet formed a contract is NOT covered by §1981 o Gregory v. Dillard’s – tends to show the need of a patron to OFFER to make a purchase Facts – 13 black individuals appeal dismissal of claims against Dillard’s based on discrimination; they were followed by SURVEILLANCE and interfered with their rights to enter into (make) a contract Holding: No §1981 claim; allegation of surveillance is insufficient; the making of a contract had NOT been initiated No facts that they attempted to purchase merchandise and were THWARTED Dillard’s DILEMMA: Can not even get to the contract formation stage if you are harassed in an intolerable way o Ex. Employee tells π to leave after π puts goods in her cart w/intent to buy = THWARTS someone from making a contract and VIOLATES §1981 o Ex. π is discriminated against during returning of goods = §1981 VIOLATION b/c it goes to ENFORCEMENT o Ex. π responds to a newspaper ad, but is harassed when she gets there = §1981 VIOLATION; contract formation if the ad says browse and you accept that offer by coming to the store Other way to regulate the Dillard’s situation is state PUBLIC ACCOMODATIONS laws Discrimination because of Race – Requirement #2 Language of Title VII vs. §1981 o Title VII text shows no distinction b/w white and black; broadly states an employer is liable for discrimination on the basis of an individual’s race o §1981 has an explicit distinction that all persons shall enjoy the full/equal benefit of all the laws enjoyed by WHITE citizens Underscores the racial nature of the discrimination §1981 addresses BUT, a white person CAN be a π (McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transport p. 638) DEFINING RACE through originalist intent o Goes to ANCESTRAL BLOODLINES; against ethnic groups; MAYBE includes citizenship/alienage (Anderson v. Conboy – leg history of §1981 included distinction b/w citizenship vs. non-citizenship) o NOT protected = national origin, religion (ex. anti-semetic animus), gender Saint Francis College v. Al-Khazraji **might not have covered this, so if you use, be broad and not specific** o Facts – π is Iraqi and denied tenure o Does “Arab” = national origin? o Broad conception of racial distinction (FN 4 pg. 679) = Caucasian, negroid, mangloid Are racial defs broad enough that Arabs, Hispanics, etc. are classified in one single Caucasian race? o Holding: §1981 reaches discrimination against an individual b/c he is genetically part of an ethnically distinctive subgroup; prove intentional discrimination based on the fact that he was Arab Orignalism – go back to the original intent and determine what the prevailing concept of race was THEN At the time of the 1866– race seemed tribal, ethnic groups relating to regions; ancestral bloodlines o Concurrence: Confusing race vs. national origin Ex. Family from the British isles whose ancestry is there moves to South Africa and has a child. What is the “race” of that child according to the 1866 conception of race? According to the concurrence, national origin is a relation to a political state = South Africa. But ANCESTRY/RACE is of the British Isles Intent required – Requirement #3 General Building Contractors v. Penn (p. 645) o Facts – Union allegedly engaged in discrimination; can employers be liable w/out proof that they individually intended to discriminate? o Holding: §1981 requires a finding of discriminatory INTENT Focuses on the 14TH AMEND roots of §1981 History – 13th amend reaching private action; 1866 act (roots of §1981); 14th amend limited to state action; Davis requiring purposeful discrimination (intent); 1870 Act reenacted 1866 Act IRONY – In Jones and Runyon the court focused on the 13th amend to apply §1981 to private conduct; St. Francis College court did not invoke social context and went back to original intent (allowing more expansive app of §1981) Respondeat superior – Requirement #4 Ex. Parent company’s policy is against discrimination, but the manager of a particular franchise refuses a customer on the basis of race. Who do you sue? o The contract is with the parent company, but they are not the ones intentionally discriminating o S.C. has NOT rejected the notion of respondeat superior – open ? Limited by 1ST Amendment values – Requirement #5 TEST = If you are NOT dealing with core 1st Amend rights of expressing political, religious, etc. views (association), then the court will NOT find the relationship so intimate as to avoid §1981 liability Ex. Group of white businessmen meet weekly for lunch. They do not collect dues, etc. but their discussions lead to business deals. They exclude female and Black businesspeople o §1981 does NOT cover women (red herring) o There would be contract issues if the members were paying dues, newsletters, etc. If there WAS a contract issue and Black businessmen could not be a part of the contract, does the group’s freedom of association restrict their §1981 liability? Unlike the Boy Scouts v. Dale where there is some political/religious tenant that triggers 1st amend rights, the mission statement here does not require that protection But, is it small enough to say the group of friends can decide who their friends are? Must be an intimate social group that should not be subject to legal restrictions Ex. KKK chapter soliciting membership and collects dues. Community enlists 300 ethnic adults for membership. KKK refuses their applications on political and religious views of the Klan o There is a CONTRACTUAL relationship here; may not be so socially intimate as would req 1st amend protection o Court found here that the org COULD exclude others on the basis of bringing people with contrary political and social view – 1st amend values trumped the discrimination Ex. Client fires attny b/c he is a “NY Jew” o If this constitutes “race,” then is the relationship sufficiently intimate and autonomous that the client should be able to prevent 1981 to apply? Court held that §1981 applied Ex. White parents advertise for a babysitter. Parents reject a Mexican-American woman. o Court might find this relationship sufficiently intimate to limit the application of §1981 even if no 1st amend expression rights are invoked. Court emphasizes family/home §1985(3) Background - §1985(3) rose out of the KKK Act (note “disguise” in the text) o Legislature needed to make a federal case out of this behavior even though it violates state criminal/tort law b/c during the Reconstruction Era, states were NOT enforcing the law - TEXT: If 2 or more person in any State/territory conspire or go in disguise on the highway or the premises of another, for the purpose of depriving any person/class of EP of the laws or of equal p&i, or preventing/hindering the authorities from securing to all persons EP of the laws; or if 2 or more people conspire to prevent by force, intimidation or threat, any citizen from exercising legal rights (i.e. voting). If 1 or more people engaged therein do, or cause to be done, any act in furtherance of the object of such conspiracy, where by another is injured in his person/property/deprivation, the party injured/deprived my have an action for damages against any one of the conspirators REQUIREMENTS: 1) State OR private conspiracy with the purpose of… 2) Depriving a person of rights under OTHER LAWS (likely only federal) §1985(3) = REMEDIAL SHELL, it does not create rights Griffin – the Court went to lengths to find a right (travel) under another law §1985(3) is NOT a self-contained statute Can NOT use §1985 to avoid the administrative reqs of Title VII (Lovetny) §1985 does not itself req state action, but it reqs that the conspiracy be aimed at rights under another law, and sometimes THAT LAW may REQ state action (does not reach private) IF THE RIGHT DEPRIVED OF IS PROTECTED ONLY FROM STATE INFRINGMENT, NO §1985(3) CLAIM Private parties can NOT conspire to violate EP RIGHTS under the 14th amend (alternative – public accommodations) United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America v. Scott o Facts – Claim by workers that they were injured by a conspiracy to deprive them of their 1st amend rights (right to freely associate) o Holding: No claim – 1st amend does NOT reach private action 3) Racially discriminatory ANIMUS NO req of intent to deprive of rights, just that actions were motivated by discriminatory animus Might not extend to other class-based animus Economic status is NOT covered by §1985; those seeking an abortion are NOT protected by §1985 (Bray v. Alexandria Women’s Health Clinic – Court’s analysis turned on factors that the animus directed at those seeking abortion rights ≠ animus based on sex; but only women have abortions so that does not make sense!) Lower courts HAVE recognized other classes (i.e. women protected in Lyes v. Riviera Beach) 4) Act IN FURTHERANCE leading to injury/deprivation of right Reading the text literally, the injured π does NOT have to be the object of the conspiracy Ex. A, B and C conspire to prevent 2 civil rights workers from crossing state lines. They force the workers’ car off the road, and it veers into Farmer J’s property and kills his cow. Does Farmer J have a claim? o (1) Conspiracy w/the (2) purpose of depriving workers’ of their right to travel o 1985(3) reads that ANOTHER is injured, that injured party has a claim ANYONE INCLUDING A BYSTANDER §1985(3) reaches PRIVATE conspiracies - Argument that §1985(3) only applies to State action o KKK Act is rooted in the 14th amend o Language reads “equal protection of the laws” – sounds like it is right out of the 14th amend which only prohibits state action o Precedent (Collins v. Hardyman); but that is distinguishable b/c it was a conspiracy to deprive people of 1st Amend rights - Griffin v. Breckenridge (pg. 707) o Facts – defs acted under mistaken belief that the owner of a car worked for civil rights; they conspired to block the passage of his car, they beat/injured the passengers w/weapons and prevented them from seeking protection o Holding: §1985(3) has NO color of state law req Language reminiscent of 14th amend – it really just goes to the fact that there must be some RACIAL (or other classbased) INVIDUOUS ANIMUS The originating statute was the Civil Rights Act of 1871 §1983 is limited to state action; if §1985(3) were also so limited, there would be no need for it! o BUT, if it is a conspiracy with state actors (or private conspiring/joining state actors) then it adds a §1983 claim as well “Person” requirement - Ex. Policemen shot and killed a fleeing suspect. 3 later came onto the scene and conspired to cover up the incident by filing misleading reports. Survivor sued all 5 officers o First 2 are liable as conspirators (does not matter who pulled the trigger); BUT, when the other 3 arrived at the scene and helped the cover-up, they are not conspiring to deprive the victim of any rights because he is no longer a “PERSON” SECTION 1983 History 1866 Act §2 – Criminal provision 14th Amendment 1870, 1871, 1874 – recodifications o §242 – criminal provision o §1983 – civil provisions Unlike §1981, it has an explicit provision for a cause of action (“civil claim”) (NOT just a remedial shell) Text: “Every person who under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any state subjects or causes to be subjected any citizen of the US to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Const and its laws, shall be liable to the party injured. Except that in any action brought against a judicial officer for an act/omission taken in their judicial capacity, injunctive relief shall not be granted unless a declaratory decree was violated/unavailable” REQUIREMENTS FOR A PRIMA FACIE CASE UNDER §1983 1. “Person” who 2. Under the color of state/local law Construing state action, even if acting contrary 3. Deprives another of (federal) rights What kind of laws establish rights? 4. Shall be liable Consider immunities Holding an individual officer/official liable – CLAIM AGAINST STATE ACTOR - Broader PURPOSE of §1983 – address inability or unwillingness of officials to enforce state law even-handedly - Misuse of power, possessed by virtue of state law and made possible only b/c the wrongdoer is CLOTHED w/the authority of state law = action taken “under color of STATE law” o Even if it is a ROGUE officer who is NOT complying with valid state law, it is enough that they are acting under the authority given to them by the state Posey v. US – civil rights activists did not stop their car until the officer involved in the conspiracy turned on his sirens o EXAMPLES: officer wearing uniform, display of badge, carrying weapon issued by dept, policy that cops are on call most of the time - Monroe v. Pape (pg. 32) o Facts – Chicago officers broke into Monroe’s home w/out any warrant and ransacked every room; detained w/out charges; denied access to attny Facts constitute a deprivation under color of statue authority of a right guaranteed by the 14th amend – deprivation of 4th amend - - - o Holding: The STATE officer acted as an instrumentality in the administration of the law can be held liable under the 14th amend Even if acting CONTRARY to state law (i.e. rogue officer), if you are a state official, you can trigger the reqs of the 14th amend State law enforcement mechanism may not be forthcoming to punish their own actors Stare decisis (like how the force of Jones paved the road in Runyon) Court relies on US v. Classic (taking precedent from the CRIMINAL counterpart) Do NOT have to exhaust state remedies Practical benefits to bringing a federal claim o §1988 grants attny fees (in state remedies, each party bears his own costs) o Broader jury pool for the jxd o Fed court judges may be more protective of fed rights o Jury might award a greater amount of damages for a fed const violation than a run of the mill state tort BUT, the abstract “importance” of a const right can NOT enter into the jury instructions to pad the award (Stachura) o Dissent: These are city policeman; isolated instances of officer defiance of the law does not constitute §1983 liability under the leg history (Congress wanted to reach conduct which was engaged in permanently as a rule or systematically came through acceptance through custom/usage); no liability for “rogue” officers Action on the job o If a state official is acting on the job w/authority of the position, it is almost ALWAYS going to be viewed as “acting under the color of state law” o Exception = public defenders (only in their representative function) Polk County v. Dodson – a crim def cannot sue his PD under §1983 PD’s position adverse to the state? o Look at the criminal justice system more broadly! PD’s are ensuring due process, fair trial, get paid by the state! Public defenders are also not immune, but that does not matter b/c under Polk they are not considered “persons” who can be sued under §1983 (see pg. 27) Action off the job o When will an off-duty officer be nonetheless viewed as acting under color of state law? FACTUAL DISTINCTIONS US v. Tarpley – officer invoked the kind of privilege he had from his position to chase down another man; announced he was an officer, etc. Parilla-Burgos v. Hernandez-Rivera – did not manifest himself as an officer; no visible badge of authority, acting like a regular patron (though he did have authority to carry a gun which he used to kill) Private individuals acting under the color of state law o Private action can be viewed as state action if there is a close nexus w/the state o Ex. A school is not a traditional public function, so must show entwinement (Brentwood Academy) o Private party utilizing societal function does NOT automatically trigger Ex. Daughter’s inheritance was going to be diluted, so she filed a fraudulent petition and a judge (who will be immune whether aware of the fraud or not (Stump)) to issue guardianship orders. Father found out and sued under §1983 for deprivation of liberty/property w/out DP. Likely NO §1983 claim against daughter b/c there is no state action here. She petitioned the court like any other citizen. Ex. Creditor and debtor sue in state court. Creditor sought prejudgment attachment to property pursuant to statutory authority. Debtor sues under §1983 for deprivation of property w/out DP. The Court found that by the creditor invoking the statutory procedure to require the Sheriff to take the property, he himself acted under color of state law o Reconcile these scenarios If the def is a private citizen invoking the exercise of judgment by an officer or judge ≠ acting under the color of state law. Def is just calling them into play (an officer/judge does not have to follow your orders, they are supposed to act according to the law) The creditor statute is different b/c it made the local officials agents of the creditor once he invoked it. There was no discretion once the order for the property was attached. Constitutional rights protected under §1983 o THEME that the Court wants to LIMIT the transformation of fed civil rights actions into STATE TORT LAW o No STATE OF MIND requirement in §1983 itself, but it comes in through the rights that are being vindicated under §1983 (it is just a remedial shell; to prove a deprivation of a const right, it may require proving some kind of state of mind) Levels of state of mind – strict liability, negligence, gross negligence, recklessness, deliberate indifference (wanton/willful disregard), intent to harm/deprive th o 4 Amendment Freedom from unreasonable search/seizure; must have individualized or particularized suspicion/P.C. to stop/seize Culpability – Intent to search/seize + unreasonableness (similar to neg) (Sacramento v. Lewis) Need an actual search/seizure to bring the §1983 claim o Ex. Police chase resulting in death of a suspect after he crashed ≠ 4th amend violation b/c officers never affected a seizure (Sacramento v. Lewis) Police chase Scott v. Harris o Can an officer take actions that place a fleeing motorist at risk of serious injury/death in order to stop their flight that would endanger others? Suspect argued that it violates his right to be free from excessive force during a seizure o Holding: No 4th amend violation; the officer’s intentional forced stop was reasonable o 8th Amendment Incorporated against the states in Robinson v. CA Scenarios: Arrest and transportation to the station = 4th amend Incarceration at station before conviction = 14th amend substantive due process Incarceration after conviction = 8th amend Culpability: If time to deliberate = Deliberate indifference for a right (higher than neg) o Subjective awareness (specific knowledge of the risk of harm) + disregard (decision to ignore the risk) o Objective assessment of gravity of risk of harm (unnecessary infliction of pain/suffering w/no relation to purpose of incarceration) o Estelle v. Gamble (pg. 886) – conditions of confinement Facts – inadequate medical treatment to an inmate Holding: Standard requires a DELIBERATE INDIFFERNECE to serious medical needs; actual knowledge of an elevated risk THEME: Const deprivations require more than the mere tort of negligence In an emergency = bad faith/malicious intent (elevated to intent to harm) o Wilson v. Seiter (pg. 887) – punishment usually requires intent Holding: Extended to require INTENT TO HARM (shift to bad faith) This higher standard also applies to EMERGENCY SITUATIONS (ex. riot) where officers do not have time to deliberate th o 13 Amendment §2 empowers Congress to eradicate the badges and incidents of slavery Herndon – it is NOT a 13th amend violation for a HS to impose a community service requirement o 9th Circuit on Racial Profiling 4th Amend – Absent reported crime, in heavily Hispanic population, Hispanic appearance is NOT a relevant factor in establishing reasonable suspicion Even if crime reported and race of perpetrator identified, “persons of a particular racial/ethnic group may not be stopped and questioned b/c of such appearance, unless there are other individualized/particularized factors which, together with the racial/ethnic appearance identified, rise to the level of reasonable suspicion/P.C.” o Equal Protection π must show differential treatment from similarly situated individuals Culpability – requires INTENT to discriminate o Procedural Due Process Culpability Daniels – need MORE than negligence (under SDP – “shocks the conscience”) o With procedural due process, there is an assumption that there is time to deliberate, so it is likely deliberate indifference (GRAY AREA) (argument that it should be intermediate – recklessness) REQUIREMENTS: 1) Protected interest – life, liberty, property o Look to STATE law to see what kinds of interests have been created Paul v. Davis (pg. 224) – no interest in reputation Facts – Police displayed the π as an active shoplifter, impairing his employment and ability to shop; defamation claim but filed §1983 suit claiming he was deprived of liberty Holding: Recognizing this would place no limits; every legally cognizable injury which may have been inflicted by a state official would establish a violation Criticisms – Plead wrong? Could have said property interest, or an injunction on the grounds that he was never adjudicated 2) Deprivation of that protected interest is attributable to the state (as opposed to a private actor) o Requiring deprivation under the COLOR OF STATE LAW 3) Deprivation done w/out due process of law (OR in a manner that shocks the conscience and thus violates substantive due process regardless of the process due) o The violation is complete if the state fails to provide due process, NOT when the deprivation itself occurs o Notice o Opportunity for a fair hearing PRE-deprivation – when feasible, the process to which someone is due is PRIOR to the deprivation Stotter v. University of TX o Facts – Stotter was a chemistry prof informed (notice) that a cleaning crew would inspect his office for fire hazard; he came to his office and his personal property was destroyed (warning letter came after the fact) o Holding: Prof had a sufficient property interest in the items. School knew when it was going to take the property so it had the opportunity for a PRE-dep process that was due (Parratt does not apply) POST-deprivation – a post-dep procedure may be sufficient if the deprivation was not foreseeable Would a pre-dep hearing be unfeasible so that post-dep is all the process to which the π is due? ONLY an interpretation of “w/out due process” – other constitutional violations (like a 4th amend violation and providing a post-dep tort remedy after) do NOT depend on this analysis PARRATT (v. Taylor) DOCTRINE (pg. 248) 1) Deprivation was unpredictable or unforeseeable 2) Pre-dep process was impossible or ineffective to counter official misconduct 3) Conduct was unauthorized (Hudson) 4) Emergency (objective belief) o Facts – When the prisoner’s hobby kit (protectable interest) was lost in the mail, that may be the deprivation, but the state provided a remedy after o Holding: Losing the hobby kit (negligence) is not something that prison officials could FORESEE in order to have a pre-dep process Hudson p. 252 o Holding: EXTENDS Parratt; even if there is an INTENTIONAL dep (guard going against policy and intentionally damages prisoner’s property), there is no way to anticipate that RANDOM event Not feasible to hold a PRE-dep hearing o Process was adequate Probable value of additional or substitute procedural safeguards o Substantive Due Process Culpability – deliberate indifference if time to deliberate; intent to harm in emergencies Standard – Arbitrary state action that “shocks the conscience” Can INACTION constitute a deprivation that shocks the conscience? Inaction ≠ liability o EXCEPTIONS = special relationship, state created danger Ex. of special relationship – incarcerated (in custody, a π’s freedom and ability to protect themselves is taken away and they are dependent on the state), institutionalized, but NO custody relationship in schools Ex. of state created – informant killed after police revealed his ID, drunk person injured after cop abandoned him DeShaney v. Winnebago County Dept. of Social Services (pg. 240) o Facts – 4 y.o. was in a coma after father beat him; social services was contacted 26 months earlier and refused to take coercive intervention; mother argues a dep of liberty w/out due process for social services failing to intervene to protect the child o Holding: SJ for state dept/officials; purpose of DP is to protect citizens from oppression by the gvnt (not to protect you from each other); social services did not cause this deprivation (it was an OMISSION) The father is the one who deprived the child of a liberty interest, but he is NOT acting under color of state law Theory that the social workers’ INACTION = dep under color of state law – Court finds that there needs to be AFFIRMATIVE participation in the child’s injuries for a 1983 claim for violation of SDP Violating equal protection through purposeful inaction Elliot-Park v. Manglona o Facts – π was in a car accident and the officers were favorable to the other driver who was Micronesian like them (failed to breathalize, false reports, etc.); officers conspired to obstruct an investigation and prosecution of the other driver b/c of an animus against the π and in favor of the other driver o Holding: const right protecting discriminatory withdrawal of police protection; even though π received some protection, what matters is she would have allegedly received more if she weren’t Korean – E.P. claim What is meant by “and laws” in §1983? o History 1871 Act §1 – no reference to any other laws Recodified in 1874 – “and laws” was added Jxd provision in 1874 – “Const or any laws of the US” Modern jxd counterpart (§1343(3)) – laws protecting equal rights o Possible interpretations Protects ALL statutory rights and const rights; protects NO statutory rights; protects some but not all statutory rights (only those guaranteeing equal rights – dissent in Thiboutout) o High water mark interpretation Maine v. Thiboutout (pg. 271) Facts – couple was deprived of welfare benefits; Maine dept of human services notified H that in computing benefits to which he was entitled for his 3 separate children, they did not consider $ spent on the 5 other children he was caring for Does 1983 encompass claims based purely on statutory violations? There are so many federal programs administered by state and local officials Holding: “and laws” = federal const and ANY kind of FED statute o Plain language = no modifier indicating that congress intended this to be restricted (if they wanted to say only “equal rights” laws, they could have) Dissent: transforming purely statutory claims under a civil rights shell (1983); this dramatically EXPANDS LIABILITY o Leg history – Did congress intent to make any substantive changes during the recodification when it added “and laws;” looks to jxd counterpart and argues that it is that equal rights restriction that Congress intended all along o Thiboutout threatened to open the floodgates b/c of all the fed statutes we now have creating rights CASE LAW STARTS PULLING BACK Civil rights statutes §1981 – requires contracting and some kind of discrimination (racial) §1985 – requires conspiracy w/the purpose of depriving people of rights under other law with an invidious animus (maybe limited to racial) BUT §1983 – More limited in requiring STATE action; but BROADER in that no required animus (just a deprivation of rights – can be a 4th amend deprivation w/out regard to discriminatory motivation) o LIMITATIONS 1) Whether the statute even creates a right that can be vindicated under §1983? RULE = if the statute is in general/AGGREGATE obligations, the court will NOT find parameters for an individual suit; obligation must bind the state rather than just condition funding on meeting standards o Pennhurst Facts – Assistance to state hospitals for a certain level of care maintained; πs argue that standard is not being maintained and deprives them of rights under 1983 under the Disability Act. Holding: Statute did NOT create an individual right, it just directed the gvnt how to follow standards (congressional directive) o Blessing v. Freestone (pg. 286) Facts – AZ mothers had children eligible for welfare services; sued director of child support agency claiming they had rights to require compliance with the statute Holding: The statute did NOT create a right in the individuals to have the state enforce child support obligations; all it did was direct how to maintain funding by meeting standards 2) Does the statute provide the EXCLUSIVE remedy? RULE = If the provision has elaborate enforcement mechanisms, it precludes any finding that the leg also impliedly authorized additional (1983) remedies; by creating a separate remedial scheme, Congress essentially withdrew the 1983 claim and requires πs to use the provided scheme o DILEMMA – Pennhurst requires the creation of a right under the statute and one way to find that is if the statute provides a remedial scheme (in that way, Congress recognized ways to vindicate a right) If it passes the Pennhurst test that there is a right, then presume a §1983 remedial suit. That is REBUTTABLE (City of Rancho Palos Verdes v. Abrams) o Case-by-case determination of LEG INTENT Explicit – congress says the remedial scheme is the only remedy Not explicit – is the special statutory scheme so COMPREHENSIVE/onerous/detailed that Congress must have intended πs to go through it and not circumvent Middlesex County Sewerage Authority v. National Sea Clammers Assoc p.283 o Facts – The environmental statute only provided injunctive relief so the πs wanted to sue under 1983 o Holding: The remedial devise provided is sufficiently comprehensive to demonstrate the congressional intent to preclude the remedy of 1983 suits 3) Court could say that Congress intended to foreclose a 1983 suit b/c it wanted the law of the fed statute to develop in some way other than through piecemeal litigation Remedies o Textual sources §1981/1981(a) – Silent about remedies/private cause of action; but always assumed §1981a (added in 1991) §1983 – EXPLICT statement for private right of action (“shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law ($), suit in equity (injunctive), or other proper proceeding for redress §1985 – “Injured party may have an action for recovery of DAMAGES occasioned by such injury/deprivation against any one or more of the conspirators” §1988(b) – discretion to award attny fees o 7th Amend – jury trial 7th amend guarantees the right to a jury trial in federal civil suits above the trivial amount in controversy of $20 – only applies to actions AT LAW, NOT equity (injunctions) Effect on Title VII Title VII claims were originally viewed as actions for equitable relief to which there was no const right to a jury trial and no statutory creation of the right o When §1981 was revived, it was a much more attractive claim for racial discrimination in employment b/c of that Title VII restriction o SUMMARY: §1981, §1985(3) and §1981 have all been interpreted to come w/in this study of remedies – can sue for injunctive relief (subject to all its limitations), general compensatory, and punitive for conduct that is at least reckless (except no punitive against a municipality) o Damages NOMINAL = insignificant amount meant to symbolize that the π did have a right that was breached by the def, but in the absence of the proof of any actual injury, the best the court can do is award nominal damages Policy: So why bother litigating? Establish PRECEDENT beyond the 2 parties or receive ATTNY FEES COMPENSATORY/ACTUAL = compensation for an actual injury to put the π in the position they were in before the action occurred; pecuniary losses/emotional distress Court looks to CL TORT REMEDIES for guidance in determining the compensable elements in a civil rights action Interpret the GAP in §1983 by looking to general tort law principles and develop a federal CL of damages (step 1) Futile PDP claim – If the same result would have happened if the π had been afforded due process, then NO compensatory damages (only nominal) (Carey v. Piphus) (Ex. Prisoner clearly did not meet reqs for parole, but was not afforded the PDP of appealing to the Board) o But if mental/emotional distress is suffered from the violation of DP, then THAT constitutes an actual injury o Prisoner lawsuits Prison Litigation Reform Act – No fed civil action brought by a prisoner for mental/emotional injury suffered while in custody w/out a prior showing of PHYSICAL injury Showing emotional distress alone is NOT enough Could argue according to dictum in Stachura that some const rights (like the right to vote) have a loss that is immeasurable. OR Characterize it as some other violation like 1st amend rather than DP b/c Carey seems to be an obstacle to DP In evaluating what compensation is necessary, can NOT consider the ABSTRACT VALUE OF THE RIGHT o Memphis Community School District v. Stachura (pg. 293) Facts – π was a science teacher who showed his students approved films about sexuality; board meeting was held and teacher was suspended Lower court allowed discretion to award damages based on the value/importance of the violated 1st amend right BENEFIT OF IN FED COURT: Judge/jury implicitly views the injury as more than just a state tort (see pg. 10) Holding: Damages based on the abstract value/importance of a const right is NOT a permissible element of compensatory damages; limited to ACTUAL injury Concurrence: SOME deprivations can themselves constitute compensable injuries; the injury = not able to exercise the right Ex. Being denied the right to vote (fn 14) – Being turned away/not able to exercise your right is a loss to that person; but it is difficult to introduce evidence measuring that PRESUMED = legal technique that allows for automatic damages (do not have to prove actual loss) PUNITIVE = punish the wrongdoer/retribution, deterrence; DISCRETIONARY Under-compensation can often occur in measuring award so punitive may boost it LEVEL OF CULPABILITY = at least recklessness o Punitive damages do NOT have to be assessed under a higher standard than the initial standard used in determining liability for the underlying the conduct o PROBLEM w/liberally allowing punitive damages is the vagueness of the reckless standard vs. the clarity of intent (Dissent) Will over-deter officials and chill their behavior (but that is addressed with IMMUNITY); federalism o Smith v. Wade (pg. 303) Facts – π was in protective custody and placed in a cell w/inmates who assaulted him. Brought a 1983 claim that his 8th amend rights were violated (requires deliberate indifference) against the officer for knowingly/should have known that the assault was likely Jury instructions – If the conduct of the def is shown to be reckless/callous disregard of or indifference to the rights or safety or others, then punitive damages may be assessed Def thinks it should be higher (intent to harm) Holding: Jury instructions ok POLICY – Officials should be guided by the underlying standard in avoiding liability, not avoiding punitive Court references CURRENT tort law rather than tracing the history of §1981 (contrast with St. Francis where the court looked to the originalist definition of race) o Congress in 1871 understood that tort law was constantly evolving; did not intend an obsolete doctrine – must have intended that the courts would not only be guided by tort principles of the time Dissent: The TEXT of §1983 makes this difficult (“Liable to the party injured…or other proper proceeding for REDRESS”) No support for punitive o Injunctive relief Court order that looks to the FUTURE; control future behavior to conform to legal requirements, rather than compensating for a past act; can be at the individual level (Ex. Gvnt employer to reinstate dismissed employee and refrain from retaliating) The court is CUTTING BACK on fed power and giving authority back to the states REQUIREMENTS: 1) NO ongoing state criminal proceedings Ex. Two groups protested against the war. Group #1 was in the criminal process (standing b/c they were arrested/prosecuted). BUT, b/c there is an ongoing case, the fed court abstains out of courtesy to the state process (WILL ONLY INTEREVENE WHEN BAD FAITH). Group #2 had solid plans to engage in the same protest, but were not in violation. The fact that group #1 was arrested made it NON-SPECULATIVE that group #2 would suffer the same fate (ripe) Group #2 has standing and the fed court has no reason to abstain 2) Wrongful state policy that continues to apply to a named π (otherwise, ripeness and standing problems) 3) π has grounds for enjoining a statute as unconst on its face (as opposed to enforcing through the court/micromanaging) BARRIERS 10th/11th amends Federal judicial restraint – self-imposed to be consistent w/federal and state relations (federalism) o Ex. §1983 excepts out any action brought against a judicial officer – injunctive relief shall NOT be granted unless a declaratory decree was violated or unavailable Constitutional constraints – fed courts have limited powers under Article III; categories of justiciability Structural reform litigation = goes beyond individual compensation and combats general operations of gvnt entity; aiming to reduce future threats to const rights If you cannot show the likelihood of some continuing/future const deprivation aimed at the π, the case may be moot Careful who you sue – direct defs vs. higher officials who did not cause the dep o Rizzo v. Goode p. 975 (Alleged actions were by police officers, but the πs sued higher officials without sufficiently tying them to the unlawful conduct) Issue with POLICE REFORM – π will have to prove that they will proceed to violate the law and be subject to the same police conduct (otherwise no standing) o Difficult test b/c it can be so speculative Lewis v. Casey (pg. 905) (Prison Litigation Reform Act – limits fed injunctive relief and even consent decrees!) o Holding: SC overturned an injunction that required a state to reform their state prison access policies to libraries; the injunction was overly broad and excessively intrusive over the state’s control of prisons City of Los Angeles v. Lyons (pg. 959) o Facts – π was stopped for a traffic violation and was placed in a chokehold rendering him unconscious and damaging his larynx. He sought a permanent injunction against the city barring the use of this tool (officers regularly applied them when they were not threatened) o Holding: Dismissed for lack of jxd; π did not have standing b/c the case is too speculative; nothing in the police policy that he or other citizens will DEFINITELY be subjected to chokeholds in every interaction (but it was not moot b/c the state-imposed moratorium will end) (still has state tort actions) Needed to prove he would have another encounter w/police (do not assume he will break the law again; O’Shea), that all LAPD always chokehold, and that the city authorized the conduct (can become usage) But it was shown that these holds cause death, and most were black! o Dissent: The decision is too restrictive and no one will have standing to challenge a policy that authorizes persistent deps of const rights. π also sued for damages and had standing for that so why not standing for the whole case? MAJORITY SEPARATES OUT THE CLAIMS TO FIND NO STANDING FOR THE INJUNCTIVE CLAIM o Alternative ways to get systemic relief If there is a claim for substantial $ damages, and the allegations would be proven to the sympathy of the jury (ex. facts in Lyons probably would have procured compensatory + punitive), and the city does not want to be portrayed as evil SETTLE FOR $ DAMAGES TO GET A CONSENT DECREE Can get the equivalent of injunctive relief if the gvnt agrees to it as part of the comprehensive settlement o Use viable claim for damages as LEVERAGE to get other systematic policy changes (go beyond what could be compelled through injunctive relief) o Defs could agree to relief that the court would not have granted Ex. (Lyons) State agrees to a moratorium on the chokehold and changes in the training program for when the hold can be used. Ex parte Young p. 33 – enjoin the continuing deprivation on its face FEDERAL IMMUNITIES Suits against federal officers o §1983 refers only to deprivation of rights under color of STATE law BUT, an officer (not the fed gvnt itself) CAN be sued for depriving a π of fed const rights under color of FED law o Bivens v. 6 Unknown Named Agents of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (pg. 18) Facts – Fed agents acting under a claim of fed authority entered π’s home and arrested him in front of his family and searched his house w/out a warrant. Holding: B/c π’s complaint states a cause of action under the 4th amend, he is entitled to recover $ damages for any injuries suffered as a result of the agents’ violation B/c there is no enabling statute, the court JUDICIALLY CREATES/implies the remedy DIRECTLY under the 4th amend itself Before this case, you could use the 4th amend violation to exclude evidence (Mapp), or enjoin officials (ex parte Young)…This case opens up Bivens actions under other rights violations too (i.e. 5th, 8th) That is just what the dissent was worried about (avalanche of new litigation) o LIMITS just like the “other laws” limits of §1983 Limitation analogous to Middlesex, where if there is already a grievance process, Congress intended it to be the exclusive remedy. But, the court is STRICTER w/Bivens – there is not even an enabling statute here and the court just implies a right of action under the const provision. If the court is already stretching it that far, it is going to be restrictive and defer to ANY remedy, even a simple administrative process, and not allow a Bivens action If the def is a private prison, that would be the better def to deter the entire organization. BUT Bivens only allows suits against individual officers (it is already a strained analysis) (Correctional Services Corp v. Malesko) Levels of immunity for state/local officials o The TEXT of §1983 says “SHALL be liable” Suggests that liability would be unqualified, but there are limits! (kind of remedy, types of damages, etc.) §1988 analysis Step 1 “Laws of the US so far as they are suitable” – Court develops a fed CL for immunities o There is such a strong history of immunity, that at the time of enactment of §1983, the immunities were so well-known and important that Congress must have had them in mind Assume that “shall be immune” is SUBJECT to the standing body of immunities even if it is not explicitly stated that way STRATEGY: A PRIVATE party who conspires w/a state official is the BEST def – they are acting under color of state law like an official, but will not enjoy any immunity! o TEST for whether Congress intended to implicitly retain immunities in §1983 = 1) Historical basis for CL immunity pre-existing the 1871 Act (Congress must have had it in mind) 2) Retaining that CL immunity is consistent w/policies of §1983 Depends on the function being performed, NOT membership in a certain branch of gvnt Disregard INTENT The purpose of immunities is that the action is immune regardless of the alleged motivation; do not want the official to have to answer to such charges. Immunity would be of little meaning if juries considered intent o Rarely ever immunity from CRIMINAL liability Except under the Speech & Debate clause of the Const (members of congress, and maybe state legs, shielded from criminal prosecution for speech/debate) This serves as a rationale to allow forms of immunity b/c criminal liability will almost always be available o ADMINISTRATIVE/MINISTERIAL FUNCTIONS NO immunity Ex. Judge hires/fires an employee – purely administrative and does not enjoy immunity BUT one prosecutor case muddles that up Goldman – if a prosecutor does not disclose exculpatory evidence, they violate the Brady rule. But, the prosecutor will be absolutely immune for that misconduct during their prosecutorial function. πs brought a case that it was the assistant prosecutor who engaged and sued the head prosecutor who was not involved in the prosecutorial function. He was deliberately indifferent to the need to train staff about the Brady rule, and should not be protected for that administrative function of running the office. The Court called it an administrative function but still gave immunity o The differentiation b/w levels of immunity dependent on the function performed (legislative, judicial, executive) is really a kind of CLASSISM o LEGISLATIVE FUNCTIONS ABSOLUTE IMMUNITY from civil liability for damages arising out of performance of legitimate legislative activities (also absolute immunity from injunctive actions, but can be enjoined from enforcing, under ex parte Young) History – tradition that legislators were entitled to absolute immunity (also extended to the state – Bogan p. 42) Why retain – o Reasons against immunity: voting out/democratic process does nothing for the injured π; just b/c one person’s rights are violated ≠ a whole group will vote them out (Ex. Arpaio) o Reasons in favor of immunity: there are winners and losers in every leg decision, so legislatures would be overexposed to litigation if a π could sue for every bad policy (separation of powers issues w/judicial interference); would inhibit/deter the entire leg process and even more so at the local level where it is personal; there are crim remedies; just don’t re-elect Scope of the function – immune from anything in the sphere of leg activity (Tenney); speeches, gathering info, issuing reports, hearings o Ex. TV interview on which a leg makes a defamatory statement in a way that violates DP? The court will likely construe the leg function to include reaching out to constituents through mass communication o Ex. If a city council takes a bribe, liable under crim law. The act of accepting the bribe is also not leg, so subject to civil liability, BUT the act of voting based on the bribe is leg and cannot be challenged Also applies to LOCAL legislative officials o Bogan v. Scott-Harris (pg. 42) Facts – π received a complaint that another employee, B, made racial slurs. B used political connections, and the city counsel (R) and mayor (Bogan) reduced B’s punishment. Mayor Bogan also called for the elimination of π’s entire dept/position. It was a formal ordinance voted on by the council and signed into law. Holding: The local officials performed a legislative function and enjoy the same immunity as fed/state legs. FUNCTION performed – voting is quintessentially legislative; even though the mayor is an exec, signing the ordinance into law is formally legislative Counter-arg: Characterize this decision as ADMINISTRATIVE, b/c the π was basically getting fired o JUDICIAL FUNCTIONS ABSOLUTE IMMUNITY for judicial functions History – judicial immunity seen in 1872 (could it really have been firmly in Congress’ mind when enacting §1983 in 1871?) Why retain – o Reasons against immunity – even if you can overturn a wrong decision, that does not deter the individual judge; no injunctive relief available o Reasons in favor of immunity – remedy through appeals; can impeach; more concrete winners and losers than in the leg (so more targeted); if they are not protected, judges will be distracted from making their decisions fair b/c of personal concern over liability Scope of the function: 1) Subject matter jxd (standard – “clear absence of jxd) always satisfied Danger – can have gross legal error by a judge but not exposed to liability if they had jxd to hear it 2) Judicial act Nature of the act itself is a function normally performed by the judge Expectations of the parties (dealt with the judge in his judicial capacity) o Ex. Sexually assaulting women in chambers is NOT judicial (Archie v. Lanier (pg. 93)); taking a bribe (ruling itself cannot be attacked, but can prosecute the bribe); TV appearance is not a main function (fuzzy in states that elect judges) Stump v. Sparkman (pg. 49) o Facts – mother petitioned for a hysterectomy for her daughter (said she was “retarded”) and indemnify the dr. performing it. Years later the daughter sued when she realized she was sterile. Mother cannot be held liable b/c she is not acting under state law (maybe under §1985(3) if she conspired); the judge acted under color of state law and violated the daughter’s DP rights o Holding: Judge is absolutely immune; his court was of general jxd so the pro error and lack of statutory authorization do not render him liable (court focuses on the absence of a statutory prohibition, rather than the absence of a grant of authority); performed the type of act normally performed by a judge; the informality of the petition did not deprive him of immunity 1) Subject matter jxd – general jxd; nothing prohibiting hearing this ex parte proceeding (error as a matter of law, but not in hearing it) 2) Judicial act Nature of the act –Dissent argues this was completely informal (no notice, no docket #, no filings) not the kind of “normal” judicial act o Majority instead applies a liberal standard and finds the lack of formality not dispositive Expectations – parties dealt w/a judge in his official capacity – mother went to the judge BECAUSE OF his authority Judicial immunity from INJUNCTIVE actions DEPENDS on the function Virginia v. Consumers Union o Reviewing state bar rulings on disciplinary matters = immune from $ damages, but NO immunity from injunctive relief o Issuing Code of Prof Conduct = ABSOLUTE immunity from $ damages AND injunctive (like legislative) o Initiating enforcement proceedings = NO immunity from injunctive Absolute immunity for PROSECUTORS Historical basis – absolute prosecutorial immunity for malicious prosecution Why retain – like judges, prosecutors are engaged in activities that would open them up to suit regularly; the threat of suit would undermine performance of duties; would dis-incentivize prosecutors from doing the right thing (Imbler v. Pacthman (pg. 61) – turning in exculpatory evidence) Scope of the prosecutorial function – LIMITED to activities intimately associated w/the judicial process; discretionary judgment o Initiating prosecution o Presenting the state’s case o Facts in a probable cause hearing (this blurs chronological linedrawing that it begins when charges are brought (Burns (pg. 99)) o Ex. Prosecutor investigates a crime by helping execute a search warrant, OR gives advice to police about legality of investigations to ensure evidence, OR statements at a press conference? (Buckley (pg. 99)) ALL more EXECUTIVE (like a police officer), and NOT sufficiently part of the step of charging someone or preparing for trial for it to be intimately associated w/the judicial process NO immunity NO immunity for PUBLIC DEFEDERS, but the court has found that they do not act under the color of state law anyway (pg. 11) (Polk County (pg. 51)) Absolute immunity for WITNESSES Only applies when acting under the color of state law, often with POLICE OFFICERS testifying (Briscoe v. LaHue (pg. 100)) (the rest of their functions are EXECUTIVE and only covered by QUALIFIED immunity) o Historical – basis of immunity for witnesses at trial o Retain immunity for police officers – Against – exposure to liability should not be inhibiting b/c witnesses are supposed to be truthful. Why not subject to liability if they testify falsely? In favor – Court balances the greater good from possibility of abuse; witness should not be fearing the possibility of repercussions o EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONS POLICY: Why do judges, legislators, prosecutors, etc. get absolute immunity, while executive officers only get qualified? Bureaucrats like judges/legs are expected and required to act objectively w/out regard to personal considerations; there are alternative remedies to control them; A.I. for judges was created BY judges; judges are necessarily disinterested; legs have built-in weighing mechanisms (2-party system) History – There was a history of CL immunity for officers when acting under good faith and having an objective ground for that belief Ex. Court reporters are not protected b/c that position did not exist, so there is no history Congress would have had in mind when enacting §1983 Why retain – In favor of immunity – Not recognizing this immunity would have a slippery slope because officers are common targets w/whom people come in constant contact; deterrence issues b/c officials have a natural incentive toward INACTION in the face of uncertainty (it is better to risk some error and possible injury than not act at all); would be suing officers who have to make split-second determinations (aren’t they more worthy of immunity than legs/judges?) Against immunity – Officials are often indemnified; the history of §1983 was to combat officers who were not enforcing the law (absolute immunity would be contrary to that policy); there is no way to reverse the decision of an officer (i.e. chokeholds resulting in death (Lyons)) unlike an appeal or voting; if it was extended here, there would be no one left to sue In Scheuer v. Rhodes, the court found that executives are entitled to QUALIFIED IMMUNITY (but it was based on a subjective test) The court ALTERED the test in Harlow v. Fitzgerald (pg. 86) b/c of PROCEDURAL reasons The difficult part of the Scheuer test was the SUBJ discretion component – very factually-oriented and required discovery or a jury question of what the def was thinking The court wants qualified immunity resolved at the SJ stage and before the def is faces discovery. If you determine it at the end of trial of whether someone is protected from $ damages, it contorts the purpose of immunity to protect defs from suit altogether, not just from damages Executive officials enjoy QUALIFIED IMMUNITY from liability for $ damages for discretionary functions IF the conduct did not violate a (federal) statutory or const right that was clearly established (at the time of the deprivation) to which a reasonable officer would have known. GO THROUGH BOTH STEPS OF ANALYSIS 1) Under our current understanding of the law, is this a violation of the constitution or some fed statute? DILEMMA: Courts want to skip this question b/c answering whether the law was unsettled (step 2) is EASIER. Could just dismiss the case b/c the law was not clearly established will NEVER answer the ? of whether the facts = a violation Cycle – If the court does NOT go through the difficult step of figuring out whether there is a violation, the law will never be clearly established! 2) If there is a violation, is the def nonetheless immune b/c at the time of the event, the law surrounding the violation decided today was NOT clearly established Stotter p.11 – constitutional rights were clearly established Gomes – the case law of what constituted an emergency circumstance was developing; so while the acts of the social workers violated a right, the notice was not clear at the time o BUT THIS ORDER IS NOT MANDATORY – Pearson v. Callahan (supp pg. 9) Court makes the “inflexibility” of Saucier NON-mandatory (stare decisis consideration that Saucier was criticized) PROCEDURAL: Under Harlow, qualified immunity must be asserted at the pleading stage, so the factual basis for π’s claims may NOT be fully developed in order to answer the violation ? in step 1 o Using scarce judicial resources on ?s that have no bearing on the outcome DANGER w/judicial efficiency that courts will just get rid of cases on the qualified immunity ? and NOT resolve problems in the law Clearly established right Need FACTUALLY ANALAGOUS/PARTICULARIZED case law from the S.C. or the state S.C. or the circuit where the violation occurred o Brosseau v. Haugen (pg. 91) Facts – H was reported by T for stealing; Officer B found out that H had a warrant out for his arrest and went to the scene. Chase ensued and Officer B ordered H out of the vehicle. H didn’t listen so Officer B crashed the window w/her gun, and shot H in the back. Officer B’s justification was that people would be injured in the path of H’s car Precedent: officer who shot a suspect who was fleeing over a face violated the suspect’s 4th amend rights Holding: Officer B enjoys qualified b/c the law under THESE FACTS was NOT clearly established. These facts including danger to others are distinguishable from the precedent in a way that makes it UNCLEAR whether shooting is a violation of the 4th amend o Wilson v. Layne **might not have gone over Facts – officers brought media reporters with them for a ridealong when they executed a search warrant; they executed the warrant on the wrong people and reporters took pics; πs sued the fed officers under Bivens and state under 1983 for violation of 4th amend rights Holding: The media ridealong violates the 4th amend (step 1), BUT the state of law was NOT clearly established at the time of the search (step 2), so the officers are entitled to qualified immunity Obj test whether the law was clearly established – look backwards and ask whether, under the circum, the officers would not have reasonably thought it violated the law (ridealongs were common practice and no opinions that they were unlawful) o Dissent disagrees here; a reasonable officer would have known that the media can’t be there, that goes outside the warrant and is more intrusive o Anderson v. Creighton **might not have gone over Facts – A was an FBI agent who conducted a warrantless search of C’s home in violation of the 4th amend. Holding: Court requires that the law be clearly established in a more particularized and relevant sense. Officer gets qualified immunity Clearly established law at the time = cannot enter home w/out a warrant, unless you had P.C. and exigent circumstances BUT, how it applies is NOT clear, especially what qualified as an exigency In some cases, can look at the TEXT of the const provision and say that an action CLEARLY violated the right WITHOUT requiring any case law to inform the right (violation is so obvious that we should not need developed precedent to answer that ?) o Ex. Lanier (pg. 93) – judge was sexually assaulting women in his chambers) o Ex. Strip search in Redding seemed outrageous, but the problem with that was there were searches under similar circum that were upheld th The 9 circuit has ADDED a 3rd component – Even if the law was clearly established, officer may still be entitled to qualified immunity if there was an EMERGENCY circumstance or was MISLED Burdens Ashcroft v. Iqbal o Holding: Twombly requirement of showing PURPOSEFUL discrimination in supervisor responsibilities applies everywhere, not just complex antitrust litigation. The court is implying into the Rules of CP that the pleading is sufficiently specific and detailed that the court thinks the ultimate claim of wrongdoing is PLAUSIBLE HERE, the allegations of wrongdoing against the DOJ go to those at the top. Once you tie in higher officials, you need more than bare allegations that they were involved PROBLEM – This is not a realistic way to proceed b/c w/out getting through the discovery, the π will not have the facts necessary for a detailed complaint Raising qualified immunity defense o Motion to dismiss (complaint) o Summary judgment (limited discovery) – if the legal right is not clearly established @ the time of the deprivation judgment for def…if it is not, proceed to trial on π’s claim (STRATEGY to avoid SJ: argue there are facts in dispute that are necessary to finding the def entitled to qualified immunity) o Motion for directed verdict (evidence) o Post-trial motion o Post-trial appeal Municipal liability o SUMMARY: A municipality enjoys no immunity (except absolute from punitive damages), but is only liable for its own custom/policy that CAUSED the deprivation. Have to make sure that the entity/dept is really of the locality and not the state, b/c the state is not a “person” and has sovereign immunity. The city will always argue that the individual official’s actions ≠ its policy. BUT, the city is liable for the violations of an officer/employee if that party established the policy and was a final policymaker (est by state law), followed an official policy that was unconst, or the deprivation was caused by a failure to train/screen. It can NOT merely be on respondeat superior theory. If there was a valid policy, the only way the officer’s actions can subject the municipality to liability is if that policy was simply window dressing and the officer’s actions represent the counterveiling custom/usage. (Could also just sue the def who directly caused the deprivation, but he will enjoy immunity if the law was not clearly established.) o Begin with the TEXT §1983: “Any PERSON”…Should that extend beyond individual gvnt officials? In Monroe v. Pape p.148, the S.C. revived §1983 by saying that state/local officials do act under the color of state law even if they are acting CONTRARY to state law so long as they are using their badge of authority. o But the legislative history of the Sherman Act (applied to a different section than 1983) in Monroe showed the Congressional animosity toward opening up municipalities to liability Dictionary Act: “The word person MAY extend and be applied to bodies politic and corporate” o Municipalities are NOT absolutely immune (Monell p. 149 overrules that portion of Monroe) Practical significance – DEEP POCKETS compared to individual defs (who might not be indemnified or juries will underestimate damages for fear that they cannot fulfill); provides another def to sue LIMITS: Must name the correct “person” o Will v. Michigan Dept of State Police (pg. 159) – a state ≠ person to be sued under §1983 (and 11th amend issues) o STRATEGY: Need to distinguish whether a department is an arm of the state or an arm of the municipality (ex. school system) The municipality, as a person, is only liable for a violation IT caused (NO respondeat superior theory) The deprivation must result from some OFFICIAL POLICY/CUSTOM of the municipality Monell v. New York City Dept of Social Services (pg. 1149) Facts – female employees sued under 1983 b/c they were compelled under official policy to take unpaid leaves of absence when pregnant; called for injunctive relief and backpay against the dept, commissioner, board, mayor and CITY of NY Holding: When execution of a gvnt’s policy/custom inflicts injury, that gvnt entity is responsible under 1983; municipalities do NOT enjoy absolute immunity (open ? – what level of immunity DO they enjoy if any) o Text – “Person” and the Dictionary Act provide inconclusive results o Policy – (court may have been more motivated by current social context (civil rights era)) Stare decisis does not tie their hands b/c it points both ways. It is the social policy of school desegregation that is important, but court needs to bolster w/original intent analysis o Original intent – statements of the leg supporting broad construction and liability; does not want to translate the hostility toward the Sherman Amend to §1983 (it applied to different leg) 1983 is more careful/limited so it should not be subjected to the historic Sherman hostility – which would have made the municipality liable for acts of the individual even if the municipality did not have notice (DeShaney – SDP does not req the gvnt to affirmatively protect people from private harm). would have obligated municipalities to keep the peace, rather than the state 1983 would only allow suit for what the municipality itself did, NOT held liable for private wrongs. Like individuals who violate rights, if the municipality does so, it is subject to liability o NO IMMUNITY (strict liability) from COMPENSATORY damages for municipalities through the actions of FINAL policymakers (Owen v. City of Independence (pg. 162)) In practice: If a city official engages in an executive function issuing a policy representing the official policy of the city, the individual AND the city caused the deprivation If at the time of the deprivation, the law surrounding the violation was not yet clearly established, the INDIVIDUAL official who executed the policy will be protected by qualified immunity (Harlow) BUT, the CITY WILL BE LIABLE Historical basis – immune for governmental functions, but not immune for proprietary (more like a private corp). gvnt policymaking vs. implementing the policy. There was also a distinction b/w discretionary functions Retaining – Under the history, if it is the custom/policy that opened the city up to be viewed as a person (rather than the implementation), it constitutes a gvnt function and immune. To get around this, the court says that §1983 did away with immunities o BAD ARGUMENT…It goes the opposite way in all other cases that the silence about immunities reflected that the immunities were retained The court also gets around the discretionary distinction in CL by saying that there is no discretion to violate the const. POLICIES – Deterrence and costspreading the result among taxpayers o These same policies that were not strong enough to justify respondeat superior in Monell and are being used here to reach the opposite conclusion o ABSOLUTE LIABILITY for municipalities from PUNITIVE damages (Fact Concerts) History – The court in Owen identified the history of immunity from compensatory damages for municipalities, but IGNORED it b/c of its inconsistency w/§1983 policies. YET, in Fact Concerts, the court gives FORCE to this same history it chose to ignore in Owen No legislative history that Congress intended to abolish the immunity through the silence in 1983 Given the hostility w/the Sherman Amend, Congress would have never allowed punitive damages Retention – assuming there was a history of immunity, is retaining it consistent w/the policies of 1983? Owen found retention for compensatory inconsistent w/1983 HERE, RETENTION OF IMMUNITY FROM PUNITIVE IS CONSISTENT o Deterrence/fairness – b/c punitive damages are to punish, you would be punishing the city, which in turn punishes the TAXPAYER, for what an individual official did w/malice Counterarg: most individual officials who are open to punitive are indemnified so that comes out of taxpayer $ too! (So why the difference here) o Voters can just condemn the official through the voting process City of Newport v. Fact Concerts (pg. 317) Facts – F entered into a contract w/city to use state park for concerts. When a “rock” group was scheduled, the city council and mayor were against it b/c it would attract an undesirable audience. Council revoked the contract under a pretext that safety procedures were not followed. π sued the city, mayor and council members on 1st amend, PDP and SDP Holding: History and policy do NOT support exposing a municipality to punitive damages for the bad-faith actions of its officials. o Council members also enjoy absolute immunity for leg function But is the contract legislative? Likely admin/executive (could have gone through some “formal” procedure like enacting an ordinance that cancelled the contract in order to be immunized (Bogan)) o Determining if there is an OFFICIAL POLICY/CUSTOM Municipalities can be liable ONLY IF their official policy/custom caused the deprivation. When the city’s highest officials – lawmakers, mayor, board of supervisor – pass an ordinance, etc. – it is AUTOMATICALLY viewed as the POLICY of the municipality Even if it is just a SINGLE decision (reaction to a case in front of them), if it comes from the top of the hierarchy it will = policy Lower level employees who make policy for the municipality: RULE = An official can make policy for the municipality if he has: 1) FINAL (non-reviewable) policy-making authority according to state/local law (also be delegation or interpretative authority) (will allow dismissal early like qualified immunity cases) 2) In that AREA of municipal business Pembaur v. City of Cincinnati (pg. 184) (plurality) – single decision o Facts – warrant to subpoena employees at a Dr.’s office. The dr. locked the door and refused to let the sheriffs in. The Sheriffs called a prosecutor who asked his supervisor what to do – chop down the door and arrest o Holding: The county is liable b/c the instruction by the prosecutor constituted an official policy Was an official policy the cause of the deprivation? This was not a formal/written policy by the council/mayor BUT, look to STATE LAW (3 votes) – Under state law, it does not say that the Board is the only policymaking body. It allows other entities like the sheriff/prosecutor to make policy Look to WRITTEN POLICY (2 votes) – Here the law was that you cannot enter a 3rd party’s home to execute a warrant; give effect to that and find that the prosecutor was just badly implementing it Look at the FORMAL DECISIONMAKING PROCESS (dissent 3 votes) – Just b/c they have the power to make policy does not mean that they did; this was too informal and not intended to be widespread general policy. o Counter: advice from someone like the prosecutor = precedent that people will rely on City of St. Louis v. Praprotnik (pg. 188) – interpretive authority o Facts – π was an architect for the city; he violated a rule he disliked and appealed his suspension to the Civil Service Commission; he received unfavorable reviews from employers for his whistleblowing; he was transferred to a menial job and then ultimately laid off b/c lack of funds o Holding: Decision by the supervisors was NOT official policy that can be attributed to the municipality. There was no official ordinance designed to retaliate against the π or other employees City charter directs who the policymakers are – mayor and alderman BUT the CSC can make further rules and definition to the general policies. THAT IS WHERE THE POLICYMAKING AUTHORITY STOPS The court will not find a trickle down to the director who transferred Even if the CSC had not established a “transfer policy,” (GAP) the unilateral decision to transfer here ≠ official policy o That’s too ISOLATED and would open up the city to liability for unknown decisions of lower level officials whose authority is not recognized by law o Concurrence: Looking to state law is too formulaic and should dig deeper to where, in reality, the policy is actually made and the power assumed It would have to reach the point of CUSTOM/USAGE for the π to have success. If there was more than an isolated incident by a nonpolicymaker retaliating for people’s 1st amend rights, it could be categorized as a pattern of practice reaching the level of official custom “Custom” may supersede a constitutionally sound written policy The top policymaker acquiesces in repeated actions. Settled practice may amount to custom attributable as policy of the municipality even if not established by those identified as final policymakers BUT, if there is a formal written policy that is lawful and custom that is bad, have to DISTINGUISH if it is policy vs. just poor implementation Ex. Change the facts of Pembaur. If the state law vested in the supervisors a final authority for law enforcement policy, the prosecutor would not be identified as a policymaker. If the supervisors issued a lawful policy and prosecutor just routinely gave contrary advice to sheriffs, which constitutes the municipal policy? o City would argue that it is not their policy, it is just a prosecutor going rogue and badly implementing, rather than creating, policy o BUT §1983 SAYS “CUSTOMS” – even if there is no official policy, you can have a custom that will render the municipality responsible. The official policy is ignored, so the real policy is reflected in practices/custom o Failure to train/screen City of Canton v. Harris (pg. 203) – If a valid policy is unconst as applied by an employee, the city will be liable if the employee was not adequately trained and the wrong was caused by that failure to train Facts – π was arrested and taken to the station but kept falling to the floor; no medical attention was every summonsed (DeShaney exception – if she is in custody, then there is an affirmative duty to protect/care) o Standard to determine if declining someone medical care is a violation of DP = DELIBERATE INDIFFERENCE (apply the same as postconviction) o City policy – jailer shall have a semi-conscious person needing medical care taken to a hospital for medical treatment (describes the exact condition of π) Holding: To give this amount of authority/discretion to police w/out TRAINING was GROSSLY NEG on the city’s part. Inadequacy of police training may serve as a basis when the failure to train amounts to deliberate indifference to the need to avoid constitutional violations o Station commanders were vested w/complete discretion about how to determine when someone needs medical assistance but no training on how to implement! (though this case should not be remanded, because the need for medical attention was obvious regardless of training) Board of County Commissioners of Bryan County v. Brown (pg. 213) Facts – π was injured by Sheriff B, and argues that the County is liable for being negligent in hiring him due to his background. o The final policymaker is actually Sheriff M – if there was some policy on his part that caused the deprivation, the county can be held liable o Theories: negligent hiring/failure to screen, failure to train π relies on Pembaur that a single act by a decisonmaker w/final authority in the relevant area = policy attributable to the municipality City argues that the single hiring decision ≠ policy Holding: Unlike an indifference to the applicant’s record, it is the supervisor’s indifference to the risk that a const violation will follow the decision that could make the municipality liable. NOT liable here o Sheriff M has to be DELIBERATELY INDIFFERENT to the RISK that B will violate the SPECIFIC RIGHT The casual screening process in 1 case (rather than a pattern) does not make it so obvious that it would result in violation of const rights Must have this HIGH STANDARD b/c of CAUSATION issues It is rare for a screening procedure to really be the causal link to the deprivation. BUT, if it is too broad, π can always trace the dep back the initial hiring (“If you hadn’t hired him, he wouldn’t be out on the street in uniform”) Dissent: Breyer wants to altogether overturn Monell - Strategy to avoid reqs of §1983 o Ex. There is a construction supervisor who violated a city ordinance by engaging in race discrimination. Either sue the supervisor or the municipality. Would probably want to sue the municipality (deeper pockets) even though there is no punitive (Owen) You still have to prove official policy. If this supervisor went against policy, then you would have to argue some custom that supersedes the official policy. That will be difficult to prove if he is just a bad egg Go under §1981 (discrimination in contract) instead! There were hints that respondeat superior liability may be available o That theory is NO LONGER GOOD after Jett – Court does NOT want a runaround of the holding in Monell Jett v. Dallas Indep School District Holding: If you are suing a municipality under a reconstruction civil rights act, you MUST USE §1983 o π can vindicate §1981 rights, equal protection, etc. but it has to be done under all the limitations judicially created for §1983 municipal liability STATE SOVEREIGN IMMUNITY 11th Amendment o The state is not subject to suit except to the extent that it consents; same goes for the U.S. gvnt (exception in Bivens is for officials) Main rationale is not wanting to drain the state treasuries o Forbids damage action against the states (Will p. 159 – “person” in 1983 does NOT include the state, even though it includes municipalities) State is NOT a proper def in a §1983 action o BUT, can sue for PROSPECTIVE RELIEF under the fiction of Ex Parte Young p. 33 Actually suing to enjoin a state official from enforcing or implementing the unconst state action/policy (who counts as a “person”) It is a “fiction” b/c the injunction is really against the office, not the official. Under Monroe v. Pape, state officials are state actors for purpose of the 14th amend and act under color of state law for purposes of §1983 even if they are violating law – we do not strip them of that status o Under Ex Parte Young, the official can be a state actor, but can also be stripped of their capacity b/c they are breaking the law by enforcing the unconst law o STRATEGY: For injunctive relief, can sue directly under the const, so π does not have the “person” barrier of §1983 Distinguish b/w a suit against the state and against a municipality o Ex. School district – if it is an entity of the state, then it is not a “person” for 1983 purposes, or even if it was, sovereign immunity protects. BUT, if it is an entity of the municipality, there are no immunities enjoyed Look to where the $ comes from, does the entity perform central state function (yes), is it a separate jural entity that can be sued in its own name (yes), does the entity have corp status of a state agency (yes – MOST IMPORTANT – something in its creation that it is the arm of the state) - Pleading o Suing an officer in his “official capacity” = suit against the gvnt entity B/c you have to show that the official is acting under the color of state law, it makes sense to sue in official capacity DO NOT DO IT THAT WAY! ESTABLISH SEPARATELY AND SUE IN PERSONAL CAPACITY Suing in personal = damages using §1983 o If you sued them in their official capacity, and they are an employee of the municipality you have the burden of proving custom. And if they are an employee of the state the court may see it as just suing the state (can’t do that b/c they are not a “person”) Suing in official = injunctive - When it’s relevant o Title VII – S.I. is implicated b/c it creates a cause of action against the state itself for damages, but get around it b/c Congress ABROGATED state immunity for this cause of action o §1981 – Maybe important b/c the text is NOT limited to “persons” o §1985 – Likely the same interpretation of “person” as §1983 o §1983 – Do not encounter S.I. directly (cannot sue a state b/c it is not a person); if you are suing municipalities or individuals, S.I. does not protect them anyway; it is significant in determining the correct def COORDINATING THE CIVIL RIGHTS STATUTES Summary o Title VII = employer liability for discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex, national origin or religion, adversely altering the terms/conditions of employment (intentional or disparate impact) o §1981 = implicitly provides cause of action for race (maybe alienage) discrimination (state or private) in making and enforcing contracts or enjoying benefits (NOT on the basis of disparate impact, requires an animus) o §1985 = liability for injury or deprivation caused by act in furtherance of class-based conspiracy to deprive a person of rights under another law (do not have to be successful in the injury intended, π can be anyone injured, and discriminatory animus can be based on any classification associated w/an elevated scrutiny under the 14th amend) remedial shell o §1983 = liability for deprivation of federal right sunder the color of state law o §1988(a) = federal court filling gap in fed law Relationship b/w Title VII and §1981 o Title VII is elaborate and complicated procedurally; it has demanding limitations period (1 year, while most state §1981 limitations are a min of a year) o Title VII has broader coverage – it is not limited to racial discrimination like §1981 o Title VII has benefits of the state/fed agency working on your behalf o Tolling Johnson v. Railway Express Agency (pg. 627) Facts – π filed an EEOC complaint for the RR’s discriminatory practices. The EEOC investigation took almost 2 years and then another year before the π had a right to sue letter. The state had a 1-year statute of limitations for §1981 claims. Holding: §1981 cause of action is NOT tolled during the EEOC process; they are separate and independent remedies (do not have to exhaust one first) and the π cannot sit on his §1981 rights in reliance on Title VII o This seems pro-π, but it really means that π’s clock starts ticking o GAP Step 1 Look to fed law – there is no judicially created tolling principal…Should the S.C. adopt such a tolling principal as a matter of fed CL? Statute of limitations are quintessentially leg linedrawing. BUT, tolling has been judicial as a “relief” from the statute. The Court does NOT go in that direction Step 2 – Look to state law – If using the statute of limitations for that particular state, couple it with THAT state’s tolling rules HERE, there is nothing that provided for suspension while an agency was trying to conciliate the matter Step 3 – Use state law if it is consistent w/§1981 policies Arguable that the policy considerations do NOT support this – If π simultaneously brings a §1981 suit it stops the willingness of the def to cooperate in the EEOC conciliation process Relationship b/w Title VII and §1985 o Great American Federal Savings & Loan Assn v. Novotny (pg. 683) Facts – π was a secretary and loan officer; he was fired for complaining about discrimination against female employees; he filed an EEOC complaint which gave him a right to sue letter. He tried to sue under §1985 asserting his Title VII rights Holding: claims cognizable under Title VII can NOT be asserted under §1985. Cannot use §1985 as a workaround of the complicated procedures of Title VII. It has its own comprehensive procedures and must be used to vindicate the rights under it (Middlesex); §1985 creates no rights, it is just a REMEDIAL SHELL EXAM STUFF PREFACE ESSAYS WITH WHETHER OTHER CLAIMS ARE DISQUALIFIED B/C OF MISSING ELEMENTS (such as intent required for §1981) ISSUE: as a question RULE: summary of civil rights statute or and standards depending on the “other” right APPLICATION: pro/con of facts to that standard IMMUNITIES REMEDIES CONCLUSION §1981 Structure: 1) Lay out the reqs of a prima facie case and that it applies to private discr 2) Denial of contract rights (goes to performance too) – draw a conclusion 3) On the basis of race – St. Francis originalist def 4) 1st amend limitations 5) Who is liable – includes respondeat superior 6) Remedies – compensatory (no abstract) (includes emotional injury) and injunctive (ex. continuing to exclude patron on the basis of skin color and repeated toward that specific π (standing)), discretionary punitive w/at least reckless 7) If it is state action – immunities Immunity intro: Whether a state actor enjoys a level of immunity depends on a two-fold analysis. Given that the text of §1983 reads “shall be liable,” the Court must interpret if Congress implicitly (through its silence) retained an immunity that (1) had a common law antecedent in 1871, and (2) retention of that immunity does not unduly conflict with the policies of §1983 as balanced with the policies supporting the immunity. EXAMPLE of municipal liability: Make sure that the individual is under a municipality, and not the state (≠ “person” (Will)). A municipality is not protected by any level of immunity for compensatory damages (Owen), though it is absolutely immune from punitive damages (Facts Concerts). It will only be liable if its official policy or custom caused the deprivation suffered (Owen). For example, city employees who are final policymakers on a certain topic, such as the city council or mayor, may always speak for the city and its final policy. In contrast, the city cannot be held accountable on respondeat superior theory for the wrongs of a lower-level employee whose actions and interpretations are reviewable by higher officials. Is the city’s policy constitutional on its face? Does the single interpretation of one person transform that decision into a policy (Pembaur) (his the decision reviewable, what is the person’s title as defined by state law, etc. (Propotnik))? If that person is a high-ranking official or if it is a pattern conforming to “custom/usage” that undermines the valid policy EXAMPLE of municipal liability: A municipality does not enjoy any immunity from compensatory damages (Monnell), however, it can only be found liable if the violation was caused by an official custom or policy (Owen). The individual who directly caused the deprivation, however, likely enjoys qualified immunity if the law surrounding the violation was unsettled at the time (Harlow). The city is absolutely immune from punitive damages (Facts Concerts). The actor violating the π’s rights must be viewed as a person with final-decision-making authority (not subject to review) often rooted in state or local law (Pembaur/Propotnik), but the Court sometimes looks deeper if a custom or usage supersedes a valid policy. Even if someone does not have final policy making authority, a higher-up (city council/mayor) may have consisted delegated that authority to this person. EXAMPLE of respondeat superior for private def in §1981: Title VII and §1981 are not mutually exclusive (Johnson v. RR) and each establish a separate claim for racial (under the originalist definition of ethnic lines (St. Francis)) discrimination in the making and enforcement of contracts. The issue has not been conclusively answered by the S.C., but it has referenced that §1981 may impose vicarious liability on the private (§1981 reaches private conduct (Runyon)) entity that employs a wrongdoer. However, if that employer is a municipality, the π cannot use §1981 to vindicate rights and avoid the limitations developed surrounding municipal liability under §1983 (Jett). A municipality cannot be held responsible under a theory of respondeat superior for the wrongful actions of its employees if they did not establish official policy of the municipality. Even under (c) of §1981 (established in 1991) extending the reach of §1981 to private discrimination, it should not be interpreted to allow respondeat superior liability in cases against municipalities. That would undermine the legislative history surrounding the policy questions about retaining municipal liability and the noted hatred toward the Sherman amendment (Monroe and Monell). EXAMPLE of conspiracy §1985(3) involving PRIVATE actor: §1985 imposes liability on any conspirator for a deprivation or injury (to any person, even a bystander) caused by a conspirator’s act in furtherance of a conspiracy to deprive a person of equal protection of the laws. A conspirator must, however, possess an invidiously discriminatory animus, which is likely limited to racial animus (though lower courts have extended it to gender discrimination). Must distinguish b/w complaints of immigrants vs. one ethnicity. Furthermore, because §1985 is only a remedial shell providing a cause of action for a violation of rights under OTHER laws, the π must identify a source for the right violated by the conspiracy. Similar to §1983, §1985 is likely limited to federal sources in an effort to confine the civil rights statutes and not transform these actions into common law tort cases. Especially if the problem does not identify any federal claims, if the def is a private actor they are not even subject to the 14th amend. It would be a stretch to find their actions as violating the guarantees of the 13th amend, which does reach private conduct. EXAMPLE of §1983 involving a PRIVATE actor: A person is subject to liability under §1983 if he or she acts under the color of state or local law to cause another a deprivation of rights guaranteed under another federal law. The defs have to be viewed as state actors capable of violating rights – such as 14th amend that protects 4th amend rights or equal protection rights that further require an intent to discriminate A private party can be found to act under the color of state law if his actions are cojoined with the assistance of a state official (usually not judicial, b/c that is just using a public function rather than conspiring (Stump), but could be entwinement (Brentwood)). Counter-args if it is too attenuated. If the actions of this private party can constitute state action, it may actually bolster a corresponding §1985 claim because it would support the conclusion that a conspiracy was aimed at violating federal constitutional rights. EXAMPLE of §1983 claim incorporating the 4th amend: If excessive force was used as part of an arrest, then the 4th amend through the 14th governs. If it was used in a post-arrest stationhouse detention, then the use of force is governed by 14th amend substantive due process standards which requires a standard of deliberate indifference to the plaintiff’s rights if the officer had time to deliberate, or intent to harm if it was an urgent emergency situation. Argue under 4th – acting under color of state law, use unreasonable force, but is that conclusion about unreasonable force (the violation) clearly established at the time of the event – executive official enjoys qualified immunity from $ damages if his conduct did not violate a federal right that was clearly established at the time (Harlow). Argue under 14th – Arguing under the 14th amend allows the defs to maybe benefit from a higher standard of culpability, b/c if the force was implemented in an urgent situation then the officer must have possessed an intent to harm. EXAMPLE of action/inaction: Substantive due process is designed to protect people from oppressive gvnt action and generally does not obligate officials to affirmatively protect citizens from harm at the hands of other citizens. Under the DeShaney doctrine, mere inaction by gvnt officials does not constitution a violation of SDP nor liability under §1983. However, exceptions are carved out – the gvnt create the danger or there is a special relationship invoking a duty to protect someone such as when they are taken into custody. Inaction may constitute a violation of equal protection under the 14th amendment, such as withholding police services based on a discriminatory intent against a person’s race (Elliot-Park – 9th circuit). EXAMPLE of holding an executive responsible for TRAINING policies: An executive officer may be liable if his training policies helped cause the conduct that violated the π’s rights, such the policy that led to an officer’s use of excessive force. Can also be liable if he was deliberately indifferent to the need to train officers to avoid constitutional violations. EXAMPLE of damages: §1985 and §1983 permit recovery of general compensatory damages resulting from actual injury (w/out consideration of the abstract value of constitutional rights (Stachura)), and punitive damages a the discretion of the jury for conduct that is at least reckless. Yet, if the right deprived of is a procedural due process right of the 14th amendment, a plaintiff does not receive compensatory damages if the same result would have happened even if provided the appropriate process (Carey). Mental or emotional distress, however, is an injury separate from the due process violation and constitutes an actual injury entitled to compensatory recovery (this is not the case in prison litigation that requires underlying physical injury). Despite the availability of money damages, defendants to §1983 claims often enjoy varying levels of immunity. A private party, on the other hand, is the strategic best defendant if they can be found to be acting under the color of state law b/c of their joined conduct with state actors and lack of any immunity protection. Furthermore, injunctive relief is permitted but is subject to extensive limitations. For example, such equitable relief is only available for irreparable injury when the plaintiff has standing and a ripe claim. The Court in Lyons emphasized that it is too speculative to assume that a plaintiff will violate the law again and thus unlikely that they would be subject to this conduct again. EXAMPLE of qualified immunity: Though the text of §1983 reads that a defendant shall be liable, the Court has implied through a basis in history at the time of 1871 and policy that executive officials acting within their executive function enjoy qualified immunity. However, under the Harlow test, an executive official will only face liability if the violation was clearly established at the time of the deprivation so that a reasonable official would be on notice. This requires that there be factually analogous and particularized case law addressing the issue. In order to develop the law in an unclear area, the court in Saucier had required that both questions of analysis – whether there has been a violation, and whether that law was clearly established at the time – be answered in that order. In an effort to preserve judicial resources, free defendants of fact-finding and dismiss cases on summary judgment, the court in Pearson made these steps non-mandatory, resulting in the vicious cycle that some questions will never be answered because it is easier for a court to dismiss a case under the 2nd question rather than answering the difficult question of whether the facts constitute a violation. EXAMPLE of §1988(a) analysis: SOL – Quintessentially legislatively created, so a federal court will likely be resistant to developing federal common law even if there is a “gap.” In that way, the court would look to the state law in that jurisdiction for which statute of limitations complies with the policies of §1983 (it will thus be a narrow holding and the statute of limitations will vary from state to state). Must choose the one that is most consistent with federal policy (i.e. a LONGER one). Survival of action – 1988 analysis provides that the fed court will borrow the survival rule of the state in which the court sits. There is a gap in the federal law regarding this issue, but the court is reluctant to judicially create fed CL addressing it. As long as the applicable state statute conforms with the policies of §1983 Q1 Section 1981 Section 1981 implicitly provides a cause of action for intentionally denying equal rights to enter into or enjoy the full benefits of a contract. It applies to private discrimination. Discriminatory Intent Section 1981 requires proof of purposeful discrimination based on race. Some courts have also applied it to discrimination on the basis of non-citizenship (“alienage”). However, it does not apply to discrimination based on national origin. Based on the understanding of the 1871 Congress, race is defined along narrow lines of ethnic ancestry. In this case, Diggs might be animated by several different kinds of discriminatory hostility: (1) national origin because Diggs harbors particular animus towards immigrants from Mexico, if undocumented, which would not support an action under section 1981 (2) noncitizenship because he told Moreno to leave after Moreno identified himself as a citizen of Mexico (suggesting he was not a citizen of the U.S.), which would be covered in some U.S. jurisdictions, or (3) the clearly covered category of race, because he initially targeted Moreno for discrimination based on Moreno’s physical ethnic characteristics of Latino skin tone and features, relating to his Mexican ancestors’ Spanish and Aztec lineage from a particular region of Mexico. Even if his motivation is mixed, however, he should prevail if a covered bias is a substantial factor in his hostility. If a court finds that non-citizenship is a protected classification, a fact-finder might draw an inference that Moreno’s mentioning a foreign citizenship was the point that drove Diggs to request Moreno to leave. In all courts, moreover, a fact-finder likely could find a clearly covered type of discrimination – race – simply on the basis of Diggs telling Moreno that other stores would better suit Moreno’s tastes, after Diggs reacted solely to Moreno’s Latino appearance, which would suggest discrimination based on Moreno’s ethnic ancestry. If Diggs indeed acted on the basis of a covered classification (rather than, for example, national origin), Diggs’ discrimination was clearly purposeful and not just the result of application of a neutral policy: Diggs reacted specifically to Moreno and his personal characteristics. I conclude that Moreno can show unlawful racial discrimination. Entering into a Contract Section 1981 is not triggered unless the plaintiff sought to enter into a contract and was refused. Simply browsing for goods or even trying on clothes is not enough. In this case, Moreno had not yet brought the coat to the cash register and offered to buy it, so he was not yet clearly trying to enter into a contract. After Diggs told him to leave, Moreno should have forced the issue by asking to purchase the coat. Moreno still might meet the threshold of contracting because he exclaimed “perfect” when trying on the coat, which might signal his intention to purchase, and he later said that he could afford to buy the coat and anything else in the store; however, an observer might think that Moreno was simply expressing satisfaction with the fit and was affirming his ability to buy that OR other goods, and that would not make a final decision to buy until he compared that coat to others in the store. On balance, I conclude that most courts would find that Moreno had not yet attempted to enter into a contract, so his section 1981 action would fail. Q2. City Employment 1. No Action under Section 1985 Based on the text’s reference to “equal protection,” section 1985 requires that the conspirators act with invidiously discriminatory intent, probably racial, and possibly extending to other forms of discriminatory intent, such as based on sex, national origin, or religion, especially in lower courts and until the Supreme Court holds otherwise. However, D and members of his senior staff seem to have been motivated by nothing more than a desire to avoid criticism from within the ranks, without any other discriminatory animus. This fact alone will preclude a suit under section 1985. 2. Action against D Section 1983 provides a civil cause of action against any person who acts under the color of state or local law to deprive another of rights under federal law. EE has a claim against D, because D acted under the color of local law by exercising his authority as the director of a City department, and D implemented the unconstitutional policy, thus directly depriving EE of his First Amendment rights to speak as a private citizen on a matter of public interest. 3. D’s Immunity D could be protected by absolute immunity, which would apply regardless of his bad intentions, if he acted in a legislative capacity, employing a functional test. D developed a comprehensive set of rules, which in some circumstances could be viewed as a legislative function. However, the City Council – the City’s legislative body – expressly disavowed any role in development of employment rules, deferring to the Mayor in the executive branch. Moreover, the rules were not made the basis of any ordinance or other formal legislative act, as seems to be significant in the case law. Consequently, D almost certainly was performing an executive function when developing the policy rules. Moreover, D’s act of firing EE was even more clearly an administrative act that would be executive rather than legislative in nature. D almost certainly does not enjoy absolute immunity. An individual performing an executive function is entitled to only qualified immunity from damages, which he normally will lose if he violated rights that were clearly established at the time of the deprivation of rights. In rare circumstances, a defendant will retain qualified immunity – even if the right was clearly established at the time of the deprivation – if the defendant was reasonably unaware of the clearly established rights due to exceptional circumstances. D normally would lose his qualified immunity, because EE’s First Amendment rights to speak on a matter of public interest as a private citizen were clearly established at the time of D’s application of the new policy amendment to EE. However, in light of the difficulty and complexity of this area of the law, and in light of the wide latitude that government employers have over employee speech, a City official might be excused for being uncertain about any limits on a government employer’s ability to curb dissent from its employees in the interests of maintaining a loyal workforce. D acted sensibly in referring the matter to the City Attorney, and D should be entitled to rely on the attorney’s opinion of the constitutionality of the new policy (even though it turned out to be erroneous), thus being reasonably unaware of EE’s clearly established right. On the other hand, D was an attorney who had practiced employment law and should thus be familiar with the speech rights of government employees. Indeed, he recognized the issue sufficiently to desire an opinion from the City Attorney. He should have more critically evaluated the City Attorney’s opinion rather than relying on its Executive Summary and Conclusion. In these circumstances, he may not have been reasonably unaware of EE’s clearly established rights. On balance, . . . . 4. Action Against the City The City will be liable only if EE can show a causal relation between an official policy or custom of the City and EE’s deprivation of rights. Official policies are the product of general rules promulgated by final policy-makers in that area of city responsibility, or even isolated decisions of such policy-makers in some cases. Custom entails a pattern of practice; the actions of D appear to be singular rather than part of a widespread pattern, so EE will need to show official policy rather than custom. In this case, the overly broad employment rule regarding loyalty, coupled with D’s application of that rule to EE, easily satisfies any form requirements for policy-making, so the question is whether D is a final policy-maker for the City on employment policies. Courts will look to local law to determine which city officials are final policy-makers; however, those final policy-makers may delegate their final policy-making authority to other city officials, or they may adopt the proposed policy-making of others through ratification. In this case, the City Charter identifies the City Council and the Mayor as final policy makers on matters of employment policies, but the City Council has deferred to the Mayor, making the Mayor the effective final policy-maker on such policies. In turn, the Mayor has assigned to D the task of drafting detailed employment policies to replace the outdated ones. The remaining question is whether (1) the Mayor has solicited proposed policies from D subject to review and final policy adoption by the Mayor, or (2) the Mayor had delegated final policymaking authority to D, thus making D a final policy-maker for the City without further review by the Mayor. In the initial drafting of the 2014 policies, the Mayor’s actions may show that he retained the final authority on employment policies, because he questioned the “collegiality” factor for promotion and pay raises and did not distribute the 2014 City Employment Policies until D modified that provision. This action suggests that the Mayor had delegated to D only the task of drafting proposed policies, which were subject to the Mayor’s review and final adoption, leaving final policy-making to the Mayor. The fact that the Mayor returned only a short passage of the policies for clarification simply suggests that D had drafted excellent rules that met the Mayor’s standards and thus could be easily adopted by the Mayor as his final policies. Moreover, the Mayor would not need to closely review every rule to retain his role as final policy-maker. Based on this pattern, the 2015 amendment regarding disloyalty was just a proposed policy that the Mayor had not yet approved, and D’s application of it was bad implementation of lawful existing City policy. On the other hand, the Mayor did not take D’s set of rules as a starting point and alter the “collegiality” provision to his liking. Instead, he simply asked for clarification of what that factor meant. That could be consistent with the Mayor delegating final policy-making authority to D on employment policies, and the Mayor wanting clarification of the meaning of a provision of D’s final policies before the Mayor disseminated the policies to other departments. He might have been satisfied if D had left the provision unchanged and had simply stated his intended meaning of that provision. On that interpretation of events, the 2015 amendment regarding employee loyalty, and D’s application of it to EE, represented official City policy carried out by D, the City’s final policy-maker on such matters.