Contraceptive Use Among Female Undergraduates in KwaZulu-Natal

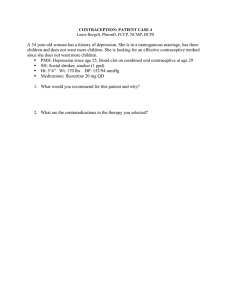

advertisement