PRIMARY CUTANEOUS TUBERCULOSIS IN A 27 YEAR OLD MEDICAL INTERN FROM NEEDLE - Copy

advertisement

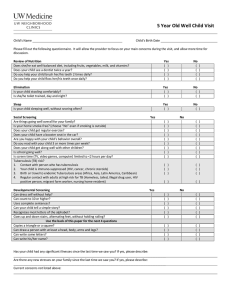

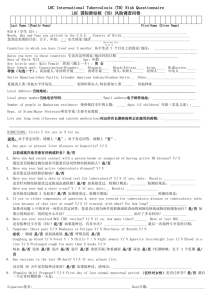

Primary Cutaneous Tuberculosis in a 27 year old medical intern from needlestick injury: a case report Karoney M J1*, Kaumbuki E K2, Koech M K3, Lelei L K4 1 Mercy Jelagat Karoney , Medical Officer, Moi University Clinical Research Center AMPATH, Nandi Road PO Box 4606-30100, Eldoret, Kenya 2 Erastus Kaumbuki Kanake, Medical officer, Ministry of Medical Services, Afya House, Cathedral Road, PO Box 30016-00100, Nairobi, Kenya 3 Mathew Kiptonui Koech, Consultant Physician, Division of Medicine, Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, Nandi Road, PO Box 3-30100, Eldoret, Kenya 4 Lectary Kibor Lelei, Senior lecturer, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Moi University School of Medicine, Nandi Road, PO Box 4606-30100, Eldoret, Kenya *correspondence to Karoney M J, karoneymercy@gmail.com Words in text -1878; Figures 4 1 ABSTRACT Introduction: Primary cutaneous tuberculosis is a rare presentation of tuberculosis and the skin barrier must be breached for infection to take place. Case presentation: The authors report a case of cutaneous tuberculosis in a 27 year old African male medical intern who sustained a needle-stick injury to his right little finger. He suffered several months of persistent swelling of the finger and developed constitutional symptoms such as low grade fever, night sweats and weight loss. The intern also developed painless axillary lymphadenopathy 6 weeks after inoculation. He underwent several debridements weeks apart and different regimens of antibiotics with no improvement of symptoms. Cultures of pus aspirated from the finger initially grew Staphylococcus aureus. This led to a delay in the diagnosis and several months of morbidity. The diagnosis of tuberculosis was made by histology. Conclusion: This case is presented to draw attention to the direct inoculation transmission of tuberculosis. Few cases of needle-stick transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from patients with AIDS have been documented. Early management should be initiated to minimize morbidity. Key words: primary, cutaneous, tuberculosis 2 INTRODUCTION Primary inoculation tuberculosis results from the direct introduction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis into the skin of a person with no previous tuberculosis infection. Skin is resistant to tuberculosis and a break in the skin barrier must be present for the infection[1]. Once the traumatized skin of a previously uninfected person is inoculated with M. tuberculosis, a tuberculous chancre develops at that site within 3 weeks. A painless regional lymphadenopathy becomes prominent 3 to 6 weeks after inoculation, and a previously negative, intradermal, intermediate-strength purified protein derivative (PPD) test converts to a positive test[1]. 3 CASE PRESENTATION A 27 year old previously healthy African male medical intern sustained a needle-stick injury from a wide bore needle (gauge 18) to his little finger while performing a lumbar puncture on a HIV-infected patient. He sustained a small lesion that oozed a few drops of blood and immediately washed it with water and soap. He was immediately started on post exposure prophylaxis Anti Retroviral drugs (ARVs): Zidovudine, Lamivudine and Kaletra for 28 days as per the Kenya National AIDS Control Program protocol. His initial rapid HIV test (Determine) test was negative and so was a PCR done on completion of the ARVs. He had no significant past medical history. The patient source, an African Female, was WHO clinical stage 4, not on ARVs and was being investigated for meningitis died soon the lumbar puncture and her results were not followed up until several months later. Two weeks after the injury, the intern had swelling of the little finger associated with a persistent dull ache for which he sought surgical intervention. Pus was aspirated from the finger and incision and drainage was done under local anesthesia. Culture of the pus grew Staphylococcus aureus sensitive to flucloxacillin on which he was started. His little finger now had an open wound that persisted for several months despite debridement and different antibiotic regimens: levofloxacin, clindamycin, ceftriaxone and vancomycin. The intern continued to clean and dress his wound daily. He developed painless axillary lymphadenopathy 6 weeks after the injury. For the next 6 months there was persistent swelling of the little finger which seemed to be spreading to the hand (Figure 1). This was associated with low grade fever, night sweats and subjective weight loss. He underwent a surgical debridement 6 months after the injury and was started on levofloxacin. Intraoperatively necrotic debris was found. Radiographic examinations done during the course of illness showed no bone involvement. Serial blood counts done in the course of illness showed persistently elevated lymphocytes and a raised ESR. Liver function test and renal tests were normal. 4 Ten months later and with no improvement of symptoms, he underwent yet another surgical debridement. Histological examination of the tissue taken revealed a chronic inflammatory process (Figure 2), granulomatous tubercles with epithelioid cells (Figure 3), giant cells of langerhans (Figure 4), and a mononuclear infiltrate but no Acid Fast Bacilli (AFB) were demonstrated on Ziehl Nelson stain. He was started on rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol for duration of two months to be followed by a four-month course of rifampicin and isoniazid. The intern had complete recovery by the end of the 6 months. DISCUSSION This case shows an example of primary cutaneous tuberculosis, a rare presentation of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis continues to pose a significant public health problem and kills about 3 million people annually [2]. It is largely an airborne infection, but skin manifestations may be caused by hematogenous spread or contiguity from foci of infection which may be active or latent. Primary inoculation, another mode of transmission [3], results from direct inoculation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis into the skin of a person who has no natural of artificially acquired immunity to the organism[4]. Cutaneous tuberculosis infection is rare, accounting for 0.1% of all cases seen in a dermatology service [5] and constitutes 1.5% of all cases of extra pulmonary tuberculosis[6] Cutaneous tuberculosis is more commonly seen in young adults because of their likelihood to sustain work related injuries and inoculation of tubercle bacilli[7]. It is also common among hospital personnel[8, 9]. The diagnosis of tuberculosis in this case was masked by an initial culture growth of Staphylococcus aureus which led to a delay in diagnosis and several months of morbidity for the medical intern. This is comparable to a case report by Opara T.N et al 2007 on tuberculous arthritis of the knee with staphylococcus superinfection in which a delay in the diagnosis led to adverse outcome[10]. Cutaneous tuberculosis continues to be one of the most elusive and more difficult diagnoses to make in developing countries due to wide differential diagnosis e.g fungal 5 infections, leishmaniasis and also because of difficulty in obtaining microbiological confirmation [11]. Diagnosis requires correlation of clinical and histopathologic findings and diagnostic testing with mycobacterial culture remaining the most reliable method in determining presence of live mycobacteria and monitoring treatment response. An absolute diagnosis consists in the demonstration of AFB on Ziehl-Nelson’s staining of the smear, prepared from material from lesions [12]. Cutaneous tuberculosis that occurs by direct inoculation is a paucibacillary disease, sparse bacilli seen on histology and microorganisms are difficult to isolate [11]. Smears, ZiehlNelson staining and mycobacterial cultures in Lowenstein-Jensen and BACTEC media are frequently negative [13]. The most prominent features of a tuberculous chancre of tuberculosis at histology are typical granulomatous tubercles with epithelioid cells, Langerhans giant cells, and a mononuclear infiltrate [14]. Histopathologic findings and isolation of M. tuberculosis in cultures of biopsy material or by polymerase chain reaction are the most useful diagnostic tools in cutaneous tuberculosis [15]. Chemotherapy still remains the treatment of choice. The management of cutaneous tuberculosis follows the same guidelines as that of tuberculosis of other organs, which can be treated with a short course four-agent chemotherapeutic regimen given for 2 months followed by a two-drug regimen for the next 4 months [12]. CONCLUSION Primary cutaneous tuberculosis is rare and should be suspected in immuno-competent as well as immunosuppressed patients who present with skin lesions failing to improve on antibacterial treatment. Healthcare workers are at risk of direct inoculation of tuberculosis. Manifestation of Cutaneous tuberculosis is so variable that a high index of suspicion is required for its diagnosis. Current diagnostic methods are far from perfect leading to a delay in starting the appropriate therapy. Complete microbiological tests should be carried out for any persistent non healing wound or ulcer. Early management should be initiated to minimize morbidity. 6 CONSENT Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-inChief of this journal. AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS MJK was the primary researcher, collected the patient’s details upon consent from both the institution and the patient, drafted and finalized the manuscript for publication. MKK assisted in interpreting the histology results and took photos for the manuscript. EKK and LKL assisted in gathering patient information and reviewed initial and final drafts of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We acknowledge the staff members of the histopathology lab at the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital for the support with specimen preparation. We also acknowledge the affiliate institution Moi Teaching and Referral hospital in Eldoret, Kenya for allowing us access to patient information. FINANCIAL SUPPORT There was no financial support 7 TABLES AND FIGURES Figure 1: Primary cutaneous tuberculosis of the little finger (after debridement) Figure 2: Inflammation; plasma cells and lymphocytes Figure 3: Epithelioid cells Figure 4: Giant cell of Langerhans 8 REFERENCES 1. Barbagallo J, Tager P, Ingleton R, Hirsch RJ, Weinberg JM: Cutaneous tuberculosis: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002, 3(5):319-328. 2. Rodrigues LC, Smith PG: Tuberculosis in developing countries and methods for its control. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1990, 84(5):739-744. 3. Sehgal VN, Verma P, Bhattacharya SN, Sharma S, Singh N, Verma N: Cutaneous tuberculosis: a diagnostic dilemma. Skinmed 2012, 10(1):28-33; quiz 34. 4. Kim JK, Kim TY, Kim DH, Yoon MS: Three cases of primary inoculation tuberculosis as a result of illegal acupuncture. Ann Dermatol 2010, 22(3):341-345. 5. Ho CK, Ho MH, Chong LY: Cutaneous tuberculosis in Hong Kong: an update. Hong Kong Med J 2006, 12(4):272-277. 6. Gawkrodger DJ: Mycobacterial infections. In: Text Book of Dermatology 6th ed. Volume Vol 2, edn. Edited by Champion RH, Burton JL, Ebling FJG. London: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1998: 1181–1214. 7. Ramesh V, Misra RS, Jain RK: Secondary tuberculosis of the skin. Clinical features and problems in laboratory diagnosis. Int J Dermatol 1987, 26(9):578-581. 8. Hooker RP, Eberts TS, Strickland JA: Primary inoculation tuberculosis. J Hand Surg 1979, 4A:270 –273. 9. Sehgal VN, Wagh SA: Cutaneous tuberculosis. Current concepts. Int J Dermatol 1990, 29:237–247. 10. Opara TN, Gupte CM, Liyanage SH, Poole S, Beverly MC: Tuberculous arthritis of the knee with Staphylococcus superinfection. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007, 89(5):664-666. 11. Bravo FG, Gotuzzo E: Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol 2007, 25(2):173-180. 12. Handog EB, Gabriel TG, Pineda RTV: Management of cutaneous tuberculosis. Dermatologic Therapy 2008, 21(3):154-161. 13. Al-Qattan MM, Al-Namla A, Al-Thunayan A, Al-Omawi M: Tuberculosis of the hand. J Hand Surg Am 2011, 36(8):1413-1421; quiz 1422. 14. Meltzer M, Nacy C: Cutaneous tuberculosis. In: Emedicine. 2006. 9 15. Almaguer-Chávez J, Ocampo-Candiani J, Rendón A: Current Panorama in the Diagnosis of Cutaneous Tuberculosis. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas (English Edition) 2009, 100(7). 10 FIGURES Figure 3: primary cutaneous tuberculosis of the little finger (after debridement) Figure 2: Inflammation (x40) plasma cells and lymphocytes 11 Figure 3: Epithelioid cells Figure 4: Giant cell of langerhans 12