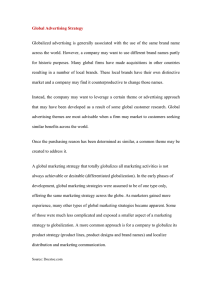

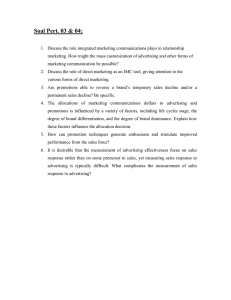

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239781321 Attitude toward the advertising music: An overlooked potential pitfall in commercials Article in Journal of Consumer Marketing · September 2011 DOI: 10.1108/07363761111165912 CITATIONS READS 32 4,272 2 authors: Lincoln G. Craton Geoffrey P Lantos Stonehill College Stonehill College 21 PUBLICATIONS 384 CITATIONS 32 PUBLICATIONS 1,950 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Book review View project All content following this page was uploaded by Lincoln G. Craton on 06 January 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SEE PROFILE Attitude toward the advertising music: an overlooked potential pitfall in commercials Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Stonehill College, North Easton, Massachusetts, USA Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to identify the causes and implications of potential negative consumer response to music in broadcast commercials. It aims to accomplish this by introducing a new consumer response variable, attitude toward the advertising music (Aam) and relating Aam’s components to advertising goals. It also aims to propose that Aam is a significant component of attitude toward the ad (Aad). Design/methodology/approach – The paper takes the form of an integrative review of the relevant literatures in the psychology of music, consumer marketing, and advertising to formulate Aam. Findings – Favorable Aam is a necessary but insufficient condition for favorable Aad in ads employing music. Furthermore, a negative Aam might cause a negative Aad. Given the numerous possible negative responses to music in a TV or radio commercial, achieving a favorable Aam among most target audience members is very challenging, especially when music-message fit is lacking. Practical implications – The paper offers cautionary advice for advertisers using music and directions for future research. Originality/value – The paper provides a novel integration of literatures in psychology and marketing/advertising. Whereas most scholars and practitioners assume that music adds value to commercials, the authors demonstrate key ways in which music can cause adverse listener reactions. Keywords Music, Music appeal, Music-message fit, Attitudes, Radio commercials, Television commercials Paper type Conceptual paper than words to communicate (McEwen and Leavitt, 1976; Dunbar, 1990). Importantly, most discussions of music in advertising assume that music adds value to and enhances the commercial’s effectiveness (Stout et al., 1990; but see Hunt, 1988; Englis and Pennell, 1994; Olsen, 1994). While popular culturalists often speak negatively of popular music in advertising as a “bankruptcy of culture,” advertisers typically describe it in glowing terms such as the “marriage of art and commerce” (Allan, 2005, p. 1) and the “catalyst of advertising” (Hecker, 1984, p. 7). Businesses risk millions of dollars in the belief that music enhances brand attitudes and consequent sales. Is this belief empirically supported? We believe the evidence is equivocal. Although scientific investigation of response to music has a long and complex history, our literature review suggests that interest in the subject among consumer and advertising researchers arose only about 25 years ago. Today a rich literature investigates the impact of music in the fields of cognitive psychology, the psychology of music, music theory, music education, and, more recently, advertising and consumer behavior (Allan, 2007; North and Hargreaves, 2008; Rentfrow and Gosling, 2003; Stout and Leckenby, 1988). The marketing contexts that have been studied include advertising, retailing, and music as an aesthetic product for sale (Kellaris and Rice, 1993). This article attempts to overcome three important limitations with this academic research on advertising music. First, it addresses the common assumption that the mere presence of music can reliably enhance the presentation of almost any product message – what we call the “music as garnish assumption.” Some empirical results cast doubt on this assumption. For instance, research investigating the effect of music on attitude toward the ad (Aad) has yielded conflicting results (Allan, 2007). Kellaris et al. (1993) cite studies reporting that the presence of music enhanced (Galizio and Hendrick, 1972; Hoyer et al. 1984), inhibited An executive summary for managers and executive readers can be found at the end of this article. Introduction William Congreve famously wrote in his 1697 epic tragedy, The Mourning Bride, “Music has charms to soothe a savage beast, to soften rocks, or bend a knotted oak.” Longfellow poetically hyped music as the “universal language of mankind” (Stout and Rust, 1986). Today, music surrounds our daily lives – both voluntarily (on car radios, home stereos, and portable music devices) and involuntarily (on hold on the telephone; in workplaces; in stores, bars, restaurants, and virtually every other public space). Approximately 40-50 percent of our waking hours are spent either passively or actively listening to music (Sloboda et al., 2001; North et al., 2004a). Much of our involuntary musical exposure occurs through mass media consumer advertising (North and Hargreaves, 1997). Music in commercials dates to the early days of radio broadcasting (Brooker and Wheatley, 1994; Kellaris et al., 1993), and it is the commonly used advertising executional element (including characters, colors, animation, setting, and pace) employed to affect consumer response to commercials (Stewart et al., 1990; Yalch, 1991). Music pervades radio and television advertising, with estimates of the proportion of TV commercials incorporating music ranging from about 42 percent (Stewart and Furse, 1986) to over 90 percent (Kellaris et al., 1993). Many commercials rely more on music The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/0736-3761.htm Journal of Consumer Marketing 28/6 (2011) 396– 411 q Emerald Group Publishing Limited [ISSN 0736-3761] [DOI 10.1108/07363761111165912] 396 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 (Haley et al., 1984; Macklin, 1988; Sewall and Sarel, 1986), or had no effect (McEwen and Leavitt, 1976; Ogilvy and Raphaelson, 1982; Stewart and Furse, 1986) on ad performance. Stout and Rust (1986), finding that a commercial lacking music was preferred to one with it, concluded that to stimulate a positive response [emphasis ours] for the brand and/or the ad with the ultimate goal of branding and purchase” (p. 28). This paper is intended to heed Allan’s (2007) and others’ (Dunbar, 1990; North and Hargreaves, 1997) call for research on the factors that determine whether music has a positive, negative, or no effect on consumer response to advertising. We propose that future research and brand advertising be guided by a more complete theoretical framework that incorporates both cognitive and affective listener responses. Our new variable, Aam, provides such a framework. In so doing, it highlights the many ways in which music might lead to responses hindering advertising objectives. Specifically, in light of the possible hazards of using music in advertising, this article has three main purposes: 1 to review and clarify the implications of current theory and research in the relevant literatures in consumer marketing, advertising, and psychology for an understanding of both positive and negative responses to music in commercials; 2 to introduce and describe the components of a new consumer advertising response variable, attitude toward the advertising music (Aam), which we propose is a significant component of Aad that can help guide an analysis of potential consumer responses to advertising music; and 3 to offer practical recommendations to advertisers for selecting music wisely. [. . .] these results indicate the possibility that music in a commercial may actually be detrimental to the objectives of an advertiser. At the very least, it [sic ] shows that considerable care should be taken in the selection of music for a commercial. It is not known yet whether music generally has negative effects, or whether the music in this particular ad was unfortunately chosen (p. 84). Similarly, Alpert and Alpert (1991) observed: In some instances music appears to increase communication effectiveness in the context of advertisements. In other circumstances, music may decrease effectiveness, for reasons that are not self-evident (p. 232). A second problem taken up in this article, then, is the paucity of research on the factors that might cause music to be ineffective or even detrimental to an ad’s success, notably the effect of disliked music. In his thorough, up-to-date literature review on advertising and music, Allan (2007) cited only four studies that included “music appeal” as an independent variable, defined simply as “liking or disliking” the music (Allan, 2007, p. 11; Allen and Madden, 1985; Gorn, 1982; Kellaris and Cox, 1989; Pitt and Abratt, 1988). Using a classical conditioning paradigm, Gorn (1982) found that music appeal influences product preferences, but his findings have failed to be replicated and have been challenged on conceptual and methodological grounds (Kellaris and Cox, 1989; Middlestadt et al., 1994). We also found a fifth study (Simpkins and Smith, 1974) concluding that people disliking a commercial’s background music will evaluate the sponsor’s credibility lower than persons hearing the message sans music. The third significant shortcoming this article considers is that research has typically characterized advertising music solely as an affective stimulus, thereby overlooking its ability to arouse in listeners cognitive involvement – thoughtful information acquisition (Scott, 1990) – and to enrich the advertising message (Morris and Boone, 1998) by communicating cognitively about attributes and benefits or a brand image or personality (Hecker, 1984, Woods, 2007). A fruitful exception has been cognitively-oriented research on music’s potential to interfere with consumers’ attention to and processing of the advertising brand message due to distraction (MacInnis and Park, 1991; Olsen, 2002; Park and Young, 1986; Stout and Leckenby, 1988; Wheatley and Brooker, 1994). This work points to the importance of “fit” between ad music and ad message, and we will argue that careful consideration of music-message fit is the most effective strategy identified to date for avoiding many of the potential pitfalls of using music in advertising. Given these three limitations, one wonders about music in commercials that some targeted consumers might respond to negatively for reasons such as finding it inappropriate for their listening situation (e.g. too peppy for workplace concentration, too sad for their happy mood, etc), unsuitable for the commercial (upbeat music for a mortuary service), annoying, boring, overplayed, inconsistent with a preferred brand’s image, or performed by a disliked musician. Might this not erode Aad and/or attitude toward the brand (Ab)? If so, Allan’s (2007) admonition applies: “It [music] should be carefully chosen and tested to predict its potential We begin by reviewing the reasons why most advertisers incorporate music into their commercials, building a list of advertising objectives that each relate to a specific cognitive or affective response component in our new variable, Aam. After summarizing relevant aspects of the well-researched construct Aad, we introduce Aam and its constituents. We continue with managerial cautions, addressing the many possible negative consumer responses to music suggested by Aam and the difficulty of achieving universal appeal of advertising music amongst a given target audience. Throughout, we highlight the need for a comprehensive model of consumer response to advertising music for guiding future research. A follow-up article will build such a model by further describing the variables, which influence Aam. The traditional case for using music in advertising It is no mystery why music dominates commercials. Hecker (1984) concluded that “music may well be the single most stimulating component of advertising” (p. 3) and that “when used appropriately, it is the catalyst of advertising” (p. 7). The case for music’s inclusion is convincing due to the potential for positive audience reaction. We now discuss key cognitive and affective responses to advertising music, stating them in terms of typical advertising objectives. In each case, we cite examples of relevant research findings. These desired responses are listed in Table I, alongside corresponding components of Aam that we will introduce later in this paper. Cognitive effects As already noted, advertising music’s cognitive effects have been underemphasized. Yet, music has conveyed consumer information since the early days when traveling merchants trolled through town streets singing about their wares and when roving salespeople’s troupes of entertainers and singers 397 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 Table I Components of attitude toward the advertising music (Aam) and corresponding advertising objectives Aam Objectives Cognitive component Level and persistence of attention to music Depth of processing of music Perceived features of music available for association Remembered features of music available for association Image suggested by music Music perceived as distinctive or not Perceived music-message fit Desired cognitive response Attract attention Enhance memory of ad content Create new music-brand associations Tap prior associations with familiar music Create a brand image Differentiate the brand Reinforce ad message with music-message fit Affective component Emotions (feelings) evoked by music Mood induced by music Emotional memories activated by music Emotional arousal response to music Hedonic response to music Desired affective response Evoke emotions (feelings) Create a mood Tap into emotion-laden memories Alter emotional arousal level Provide a positive hedonic experience attracted crowds in the town square. Listeners who liked the music or found it intriguing were held captive, ready to receive the marketer’s message. Researchers have explored the ability of music to achieve seven cognitive effects that relate to cognitive advertising objectives: attract attention, enhance memory of ad content, create new music-brand associations, tap prior associations that consumers have formed with familiar music, create a brand image, competitively differentiate the brand, and reinforce the ad message via music-message fit. 2 Attract attention Music in broadcast commercials serves to attract and hold attention to the commercial and the brand because it can intrusively gain and maintain the interest of otherwise disengaged audience members (Hecker, 1984; Kellaris et al., 1993; Macklin, 1988). This is important for getting noticed in today’s cluttered media environments (Hunt, 1988). Especially attention attracting is music that is novel, i.e. “interesting,” “surprising,” etc. (Brooker and Wheatley, 1994) and that makes people feel good (Isen et al., 1978). 3 Enhance memory of ad content Marketers believe that music is more memorable than words. The literature suggests four factors enhancing memory through music: 1 Well-learned music promotes verbal recall. Empirical evidence indicates that words are better learned and recalled when set to music than when spoken if the music is simple, repeated, or well learned (Bartlett and Snelus, 1980; Rubin, 1977; Wallace, 1994; Yalch, 1991). For instance, Rubin (1977) discovered that verbal recall was improved when cued with the melody of a well-known tune. This effect has clear implications for commercial lyrics involving the product or ad message. Wallace (1994) cites prior studies showing that hearing a melody can cue the text of a song and, conversely, that seeing or hearing the text can cue the melody over very long time delays: 4 Music is a rich structure that chunks words and phrases, identifies line lengths, identifies stress patterns, and adds emphasis as well as focuses listeners on surface characteristics. The musical structure can assist in learning, in retrieving, and if necessary, in reconstructing a text (p. 1471). 398 Rhyming in music is another effective memory cue, working by constraining the memory search to the to-beremembered word (Bower and Bolton, 1969). Music promotes rehearsal of the ad message in lyrics. Rehearsal is the silent, mental repetition of a piece of information in short-term memory. Music provides a means for rehearsal of ad content; as a listener hums or sings an ad song, he/she rehearses it and hence better remembers it (Macklin, 1988). Music supports rehearsal by making it pleasurable (Zuckerkandl, 1956, cited in Scott, 1990) and because it is inherently repetitive. Music leads to the formation and cueing of memory associations with ad content. Even when audience members cannot remember the message argument, ad music creates an auditory memory that can assist recall of an ad’s visual and emotional elements (Clow and Baack, 2003, p. 320), including the sponsor. Sometimes musical cues elicit images associated with a product (Stewart et al., 1990). Edell and Keller (cited in Stewart et al., 1990) suggest that music can serve as an effective retrieval cue in an integrated marketing communication campaign, such as when a radio commercial’s music reminds listeners of images stored during previous exposure to that music in a television commercial. A final factor promoting ad recall through music strikes us as particularly important: Music can enhance brand recall via music-message fit. “Musical fit,” “music-message fit,” or “music-message congruency” (Kellaris et al., 1993) is the perceived appropriateness of the music’s meaning and feelings to the commercial’s message. Music-message fit means that music is integrated with the brand message (e.g. a commercial for a real estate company targeted to Baby Boomers featured the classic rock tune “Our House”). Brand recall can be enhanced through personally relevant music that “fits” the message (Allan, 2006; Brooker and Wheatley, 1994; Heckler and Childers, 1992; Kellaris et al., 1993; Macklin, 1988; MacInnis and Park, 1991; North et al., 2004b; Olsen, 1995; Roehm, 2001; Shen and Chen, 2006; Shen and Chen, 2006; Stout and Leckenby, 1988; Wallace, 1994; Wheatley and Brooker, 1994; Yalch, 1991). Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 Create new associations between music and brand Music creates meaning when it becomes linked to the brand (Zhu and Meyers-Levy, 2005). This increases the likelihood that consumers will think of the brand whenever they hear the music, much like associating the Lone Ranger with the William Tell Overture (Sutherland and Sylvester, 2000). Familiar examples include “Like a Rock” for Chevrolet trucks (Clow and Baack, 2003) and the Rolling Stones’ “Start Me Up” for Microsoft (Sutherland and Sylvester, 2000). Reinforce ad message with perceived music-message fit We noted above that music-message fit can influence brand message recall. Other empirical work suggests that how positively a listener responds to a commercial’s music also depends on whether the ad’s musical meaning and style are consistent (fit) with the ad’s meaning and brand image (MacInnis and Park, 1991; North et al., 2004b; Stout and Leckenby, 1988). For instance, Oakes (2007) discovered that high congruity between advertising message and the music’s mood, genre, score, image, and tempo all contributed to communication effectiveness by enhancing recall, brand attitude, affective response, and purchase intention. It has been previously demonstrated that purchase probability is boosted when music is used to generate emotions congruent with the brand’s symbolic meaning. North et al. (2004b) discovered that musical fit resulted in enhanced recall of products, brands, and ad claims, and it boosted Aad and purchase intention. A “fitting fit” can thus enhance the brand message as well as enhance recall of it (Alpert and Alpert, 1991). Trendy, upbeat music in Starbucks commercials is appropriate since Starbucks sells an uplifting coffee-drinking experience in stores featuring comfy furniture, funky décor, and way-cool ambience. Tap prior associations with familiar music According to classical conditioning theory, the new mental associations that are fashioned between a brand and its advertising music can draw on previous associations consumers have formed with the music, such as information about location (Caribbean, Wild West), period of time (eighteenth century), or environment (relaxing on the beach) (Dunbar, 1990). Similarly, familiar music can imbue the brand with symbolic associations. For instance, Christmas carols featured in retail ads could link the merchandise to seasonal thoughts of goodwill and benevolence. Patriotic music played in the background of a commercial for a political candidate might trigger thoughts about a sense of duty to one’s country. And music from a particular era can tap into autobiographical memories (e.g. 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s tunes mine Baby Boomers’ memories of growing up). Affective effects Although music can affect consumers’ cognitive responses, reactions to music are usually conceptualized as being emotional or affective (Chebat et al., 2001; Meyer, 1956, as cited in Kellaris and Kent, 2001; Morris and Boone, 1998). Music has the potential to arouse listener affect (Gorn, 1982; Park and Young, 1986; Stout and Leckenby, 1988), conveying meaning in terms of feelings and moods, ranging from sheer horror or revulsion through excitement to an extremely gentle or romantic ambiance (Dunbar, 1990). “From Plato to the most recent discussion of aesthetics and the meaning of music, psychologists have been fascinated by music and its ability to create emotional responses in listeners” (Stout and Rust, 1986, p. R86). Research on affective responses to music is rooted in the psychology of music literature, which consistently finds links between music and affect (Clynes and Nettheim, 1982 cited in Stewart et al., 1990; Juslin and Sloboda, 2001, Juslin and Västfjäll, 2008). In the marketing literature, the affective influence of ad music has focused on both advertising and retail contexts (Alpert and Alpert, 1990; Fried and Berkowitz, 1979; Morris and Boone, 1998; North and Hargreaves, 1996). Unfortunately, the emotion terminology found in both the marketing and psychology literatures varies significantly. We use the inclusive term “affective response” to refer to the full range of possible emotion-like reactions. There are five aspects of affective response that researchers have explored and that can be stated as advertising objectives: music’s ability to evoke emotions, create a mood, activate emotion-laden memories, alter emotional arousal levels, and provide a hedonic experience (see Table I). Create a brand image The formation of associations suggests that music can be used to help craft a brand image – a set of associations reflecting a brand’s personality (Kassarjian, 1971; Onkvisit and Shaw, 1987; Sirgy, 1982; Wells and Beard, 1973). For example, jazz and classical music connote sophistication, country suggests down to earth, and rock indicates active, rebellious, and hip. In fact, musicians working in the advertising profession unanimously want a clear, simple creative brief outlining the brand personality (Dunbar, 1990), which is understandable in light of several studies linking personality and social identity to music preferences (for a discussion, see Rentfrow and Gosling, 2003, 2006). Advertisers seek the right chemistry between brand image and music, such as Target’s use of “Hello Goodbuy”, a pun version of the Beatles’ “Hello Goodbye” (Howard, 2008), or the use of dissonant music in anti-drug ads (Kellaris and Kent, 1991). Differentiate the brand Most advertising creates clear-cut, positive competitive brand distinctions. A seller must “differentiate or die!” both via tangible physical differences (Subway healthy sandwiches) and through intangible psychological distinctions. Consider how Subway is psychologically positioned through its unique brand name, positioning (healthy fast food), trade character (Jared Fogel), brand image (for fit, healthy folks), catchy packaging and graphics (distinct white-and-yellow arrowed logo), slogan (“Eat fresh”), and most importantly for the present discussion, music (perky “five-dollar foot-long” jingle). When a brand lacks objective advantages and is relatively simple in nature, persuasion can occur through distinguishing ad elements, including music (Batra and Ray, 1983). As legendary adman David Ogilvy famously quipped, “If you have nothing to say, sing it” (Ogilvy, 1984, p. 111). In fact, jingles are known as “audio brands” and “audio logos” since they identify and distinguish brands. Evoke emotions (feelings) Bruner’s (1990) review of both marketing and non-marketing uses of music revealed that music conveys emotional meaning and stimulates feelings, which might positively affect Ab, leading to brand purchase (Rossiter and Percy, 1991). For instance, advertisers such as Hallmark and Kodak use music suggesting their brands contribute to warm and loving feelings (Hunt, 1988). 399 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 Create a mood Gardner (1985b) defined mood as a fleeting, temporary feeling state, positive or negative, usually not intense, and not tied to a specifiable behavior. Along with other advertising executional elements, music can be an especially powerful stimulus to help craft a mood, atmosphere, or tone of voice for the commercial (Bruner, 1990; Simpkins and Smith, 1974). For example, music sets a commercial’s pace, thereby contributing to its mood (e.g. hurried and harried versus easy going and relaxed). A large and varied literature in social, clinical, and personality psychology has documented music’s ability to alter people’s moods (for a review, see Västfjäll, 2002). Many marketing studies demonstrate that mood affects attitudes and behavior (Alpert and Alpert, 1991), and mood state might enhance recall (Gardner, 1985b). However, little marketing research has examined the influence of music in changing people’s moods (Wheeler, 1985). Mitchell (1988, cited in Stewart et al., 1990) and Alpert and Alpert (1990) were able to manipulate consumers’ moods via music. Galizio and Hendrick (1972) found that students who heard lyrics with guitar accompaniment checked off more mood adjectives than did those hearing identical lyrics without accompaniment. Lively music can enhance mood, thereby positively affecting purchase intention (Alpert and Alpert, 1990; Kellaris and Mantel, 1996; Morris and Boone, 1998). Mood is usually conceptualized as an affective state (MacKenzie and Lutz, 1989), and some theorists believe that music can associate moods with the brand without any intervening cognitions or conscious information processing (Alpert and Alpert, 1989, 1990, 1991). Others believe that the induced mood entails some cognitive activity on the listener’s part, resulting in recall of positive (negative) thoughts associated with the positive (negative) mood (Isen et al., 1978; Wheatley and Brooker, 1994). For instance, under high cognitive involvement, music can influence the nature and amount of issue-relevant thinking by making “mood-congruent thoughts” more accessible in memory (Gardner, 1985b). between the degree of emotion experienced when listening to a tune and the preference for it, regardless of the nature of the emotion (e.g. cheerful pieces were not rated as more pleasant than sad ones). Galizio and Hendrick (1972) found greater emotional arousal and more persuasion with the presence of guitar accompaniment to a folk song. Music can also be relaxing, decreasing emotional arousal, which is important for products that relax consumers, such as pain relievers, resorts, and beer (Hecker, 1984). Provide a positive hedonic experience Affective responses may give rise to a valenced hedonic experience, i.e. they may be experienced as positive (relaxation) or negative (anxiety), although unvalenced emotions are also possible (surprise or alertness). Melodies can affect the favorableness of people’s feelings. For example, moderately energetic music and moderately novel music can both heighten stimulation, thereby providing positive hedonic value (Zhu and Meyers-Levy, 2005). Music can be used purely as entertainment, thereby creating a pleasant hedonic experience and softening up consumers for the sale. Instead of hard selling audience members with words, advertising lyrics “tend to wash over us rather than invite us to intellectualize [. . .] Setting the words to music somehow takes the edge off what might otherwise be a strident message” because we process lyrics and music in terms of “enjoy/don’t enjoy” rather than in terms of “true” or “false” (Sutherland and Sylvester, 2000, p. 105). And, music in commercials is processed more as an experience full of fantasy and feelings than as a faithful representation of reality, resulting in less likelihood of audience members counter-arguing with the message (Sutherland and Sylvester, 2000, pp. 105-6). The seven cognitive and five affective advertising objectives (effects) described above correspond to the seven cognitive and five affective components constituting our new response variable, Aam (see Table I). Because Aam is proposed as an important component of Aad, before describing Aam and its constituents, we first briefly summarize relevant aspects of what is known about the well-researched response variable Aad. Tap into emotion-laden memories Music also makes people more aware of emotions they have previously experienced when listening to that music (Dunbar, 1990), and it can become associated with either positive or negative emotion-laden memories (MacInnis and Park, 1991). Melodies become affiliated with pivotal emotional life events such as birthdays, first dates, and family vacations, thereby evoking nostalgic feelings. The cognitive associations that are tapped by familiar music (as discussed above) typically will be “tagged” with emotions: Christmas carols lead to both thoughts and feelings of goodwill because they draw on emotionally charged memories. Attitude toward the ad (Aad) Attitudes are typically conceptualized as predispositions to respond in a consistently favorable or unfavorable manner toward an attitude object (AO), where responses can be cognitive, affective, and/or behavioral (Zanna et al., 1970). As relatively stable and enduring predispositions to think, feel, and behave, attitudes are considered useful predictors of behavioral intentions (Mitchell and Olson, 1981). At root, brand advertising concerns shaping the customer brand attitudes that guide buyers’ decision making, and advertising’s effectiveness is often evaluated based on how large and favorable a brand attitude modification it induces in targeted customers. Aad, a widely used consumer attitudinal response construct, is defined as a “predisposition to respond in a favorable or unfavorable manner to a particular advertising stimulus during a particular exposure occasion” (Lutz, 1985), or as “an individual’s evaluation of and/or affective feelings about an advertisement” (Park and Young, 1986). “A strong managerial relevance to advertisers, coupled with the welldefined theoretical background of multiattribute attitude models (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975), has generated considerable research into Aad” (Biehal et al., 1992, p. 19). Aad is conceptualized as a situationally bound construct that Alter emotional arousal level Researchers typically associate emotional arousal, or intensity of felt emotion, with physiological responses (e.g. changes in heart and breathing rate, galvanic skin response or “sweaty palms,” pupil dilation, etc), suggesting that a pop song that makes the heart race might do likewise for a brand (Dunbar, 1990). Thus, music not only evokes particular emotions but can influence how strongly we experience those emotions, as when a slow tune elicits a relaxed, happy feeling (low or moderate arousal) but the same tune at an upbeat tempo creates a pumped-up, euphoric feeling (high arousal). Two early studies (Gatewood, 1927; Shoen and Gatewood, 1927, both cited in Finnäs, 1989) show a positive correlation 400 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 Attitude toward the advertising music (Aam) occurs during a particular exposure to an ad rather than at another point in time, such as following repeated exposure to it (Lutz, 1985; MacKenzie and Lutz, 1989). As a time-bound construct, Aad should have its maximum impact on other response variables such as Aad and buying intentions at or immediately following ad exposure and is likely to be less enduring than other attitudes like Ab and attitude toward advertising in general (Lutz, 1985). Aad is considered by some researchers as solely evaluative or affective, not entailing cognitive or behavioral reactions (MacKenzie and Lutz, 1989). However, Shimp (1981) and Lutz (1985) conceptualized Aad as having both cognitive components (e.g. the presentation is perceived as humorous or the endorser as attractive) and affective components (e.g. triggering an emotional response such as a particular mood or feeling like love, joy, or irritation). Other researchers have also adopted Shimp’s (1981) and Lutz’s (1985) viewpoint that A ad has both cognitive and affective dimensions (Biehal et al., 1992; Edell and Burke, 1987, cited in Burke and Edell, 1989; Gresham and Shimp, 1985; MacKenzie and Lutz, 1989) and, based on the weight of the evidence, we concur. According to the dual-mediation hypothesis, consumers can have a positive Aad either because: . they have a favorable cognitive response (e.g. the ad provides them with useful information); or . they have a positive affective response (e.g. they gain good feelings from the ad) (Brown and Stayman, 1992; Homer, 1990; MacKenzie et al., 1986). Interest in music and consumer behavior grew significantly during the 1980s as a result of the above research on Aad (Gorn, 1982; North and Hargreaves, 2008; North et al., 2004b). The finding that emotions influence Aad and the intuition that such emotions can be created by music led to a number of studies of music’s influence on purchase decisions and other variables. However, the direct effect of ad music on Aad per se received little attention, and the studies that do exist have generated mixed results. For instance, Brooker and Wheatley (1994) reported a marginally significant effect of music placement on Aad, with music-as-introduction causing more favorable Aad than music-as-background. Macklin (1988) found that the presence of music did not affect Aad in children. In the next section, we elaborate on our view that consumer response to advertising music is an important component of Aad, and that it is itself an amalgam of many cognitive and affective components. Overview of Aam Although a number of researchers have studied music’s influence on Ab (Allen and Madden, 1985; Brooker and Wheatley, 1994; Gorn, 1982; Kellaris and Cox, 1989; Macklin, 1988; Middlestadt et al., 1994; Morris and Boone, 1998; Park and Young, 1986; Pitt and Abratt, 1988), our literature review failed to find a variable capturing listeners’ complex attitudes toward the advertising music itself and how such a variable could be a part of Aad and thereby influence Ab. Therefore, we propose the new variable Aam, depicted in Table I. Paralleling Lutz’s (1985) definition of Aad, we define Aam as a predisposition to respond in a favorable or unfavorable manner to an ad’s music during a particular exposure occasion. Following Park and Young’s (1986) conception of Aad, Aam includes cognitive and affective components. In its most simple form, Aam can be construed as synonymous with “music appeal.” Thus, a researcher looking for a “rough and ready” measure of Aam might simply employ a single Likertscale item ranging from “dislike very much” to “like very much,” as is often done in measuring Aad. However, we believe that a more powerful approach would be to incorporate the cognitive and affective variables shown in Table I, each of which corresponds to one of the advertising effects discussed in the previous section. Because each of these components can be either positive or negative – that is, they each can contribute to a favorable or unfavorable Aam – using a multi-item measure of Aam would allow researchers to capture the multi-faceted and sometimes contradictory nature of consumer attitudes toward a given piece of ad music. Moreover, operationalizing Aam in this way may help marketers and researchers characterize, study, and weigh the trade-offs involved in selecting particular candidates for advertising music. Aad has been used as an independent variable in a number of studies (Babin and Burns, 1997; Lee and Mason, 1999; McQuarrie and Mick, 2003; Pope et al., 2004). Aad was introduced conceptually as an important mediator of Ab, purchase intention, and eventual brand choice by Shimp (1981), and this was confirmed empirically by Mitchell and Olson (1981) and Moore and Hutchinson (1985). It is now generally believed that Aad affects Ab. If thoughts and/or feelings created by the ad are favorable (unfavorable), the consumer’s attitude toward the advertised brand might also become favorable (unfavorable). Aad’s mediating effect on Ab has been reported in a number of studies (Burke and Edell, 1989; Brown and Stayman, 1992; Gardner, 1985a; Gorn, 1982; Homer, 1990; MacKenzie et al., 1986; Mitchell, 1986; Mitchell and Olson, 1981; Muehling and Laczniak, 1988; Stayman and Aaker, 1988). Aad’s influence has also been confirmed on purchase intention, both indirectly via Aad’s impact on Ab (Homer, 1990; MacKenzie and Lutz, 1989; MacKenzie et al., 1986; Mitchell, 1986; Mitchell and Olson, 1981; Shimp, 1981) and directly (Gresham and Shimp, 1985; MacKenzie et al., 1986). Aad also affects brand choice directly as well as indirectly through Ab (Biehal et al., 1992). Researchers have also examined Aad as a dependent variable and have confirmed the direct effect of emotional feelings on Aad (Batra and Ray, 1986; Edell and Burke, 1987, all cited in Machleit and Wilson, 1988). MacKenzie and Lutz (1989) incorporated this and other work into a detailed structural model of the determinants of Aad. Taken together, studies of Aad show that it influences and is influenced by key consumer variables and is a complex function of consumer attitudes toward the advertiser, the message, emotions aroused by the ad, the medium in which the ad appears, and the creative execution (MacKenzie and Lutz, 1989). The components of Aam The following are the key elements of Aam, as outlined in Table I. We briefly define each one and relate it to its corresponding advertising objective discussed above. In the remainder of the article, we discuss how each element can contribute to a favorable/unfavorable Aam and the difficulty of achieving favorable Aam among most target audience members. 401 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 Cognitive components . Level and persistence of attention to music. This component of Aam refers to whether the ad music has contributed to the long-standing advertising goal of gaining and holding the consumer’s attention. This will in turn affect whether and how much the consumer attends to the ad as a whole. . Depth of processing of music. This construct from cognitive psychology (Craik and Lockhart, 1972; Craik and Tulving, 1975) relates to the enhance memory of ad content advertising objective. Building on the previous component, it refers to what aspects of the ad music draw the consumer’s attention and specifically, the “level” of processing of the music in which he/she engages. Deep- or semantic-level processing focuses on the meaning of the music while shallow-level processing focuses on surface features of the music such as the sung melody, the timbre of one of the instruments, or the physical appearance of a performer. As we will elaborate in the next section, the link between this response component and memory for ad content appears to be quite complex. . Perceived features of music available for association. This is relevant to the create new music-brand associations objective. It captures elements of the ad music the consumer has detected from among the wide range of features present (structural features of the music such as rhythm or melody, its expressed emotion, the musical style, etc.) and especially whether these are positive, negative, or neutral from the consumer’s point of view. . Remembered features of music available for association. This ties in with the tap prior associations with familiar music advertising goal. Similar to the previous cognitive element, this captures what these prior associations are (especially perhaps, how common to most people or idiosyncratic to the consumer they might be) and whether the consumer views these associations as positive, negative, or neutral. . Image suggested by music. This refers to the “personality” of the music as perceived by the consumer, such as whether it is sophisticated, sexy, or lighthearted. In discussing the create a brand image goal, we noted that a brand personality can be molded either as music creates new associations or as it piggybacks off of existing associations. . Music perceived as distinctive or not. This concerns the differentiate the brand objective. We propose that the consumer makes a distinctiveness judgment, representing how unique versus prototypical he/she considers the music to be and the extent to which he/she views this level of uniqueness as favorable or unfavorable. Distinctive music that is viewed favorably (unfavorably) will help to positively (negatively) differentiate the brand. . Perceived music-message fit. Linked with the reinforce ad message with music-message fit objective, this captures the consumer’s judgment of how well the music suits the message, with high fit leading to a more favorable attitude and low fit creating possible dissonance and/or confusion. For instance, an upbeat tune could be used for a brand positioned as “fun.” Given the importance of communicating about the brand as an overarching advertising objective, we believe this component is crucial. . . . . intense they are, and how favorably or unfavorably the consumer views those emotional experiences. Mood induced by music. Related to the ad objective to create a mood, this component of Aam captures whether the ad music leads to mood induction, how favorable/ unfavorable the mood is, and whether the mood is consonant with the brand’s message and image, all from the consumer’s point of view. Emotional memories activated by music. Related to the tap into emotion-laden memories ad objective, this factor reflects whether such memories occur and how favorably the consumer views them. Emotional arousal response to music. One advertising goal is to alter emotional arousal level. This element concerns whether any changes in emotional arousal occur as a result of exposure to the ad music, and whether or not these changes are viewed favorably by the consumer. Hedonic response to music. A final ad objective is to provide a positive hedonic experience. This variable captures how pleasant/unpleasant the consumer finds the ad music to be. Implications and directions for managers Based on the components of Aam, we now provide a more detailed and comprehensive set of cautions for advertisers considering using music and explain why achieving universal music appeal is an elusive advertising goal. This contributes significantly to the literature since, to date, the primary negative influence of music considered in the academic marketing literature is the work mentioned above exploring how music can be an attention-grabber that is irrelevant to the message and therefore detracts from the processing of message content. Every component of Aam provides a challenge Here, we offer suggestions for advertisers regarding wise selection of music and warnings based on each of the elements of Aam. Poor performance on one or more of these dimensions can defeat the purpose of using music in commercials or at least lessen its positive impact. Cognitive components Level and persistence of attention to music. People rarely enjoy listening to music involuntarily (North et al., 2004b), which is the case with most ad music. We are not aware of any research exploring listeners’ ability to “tune out” music they would rather not listen to; anecdotally, this is very difficult for many kinds of common musical stimuli. The ability of attentiongaining music to distract listeners from the message and negatively affect brand recall (Park and Young, 1986; Wallace, 1994; Wheatley and Brooker, 1994) is a huge issue. We believe that not just brand recall, but Aam and thus Aad, can be negatively affected when ad music commands an undesirable level of the consumer’s attention. Somewhat paradoxically, a favorable consumer attitude toward the amount of attention elicited by ad music may in some cases be achieved when that music is easily ignored. For instance, high-involvement consumers might regard their low level of attention toward unobtrusive background music in an ad favorably if they are motivated to attend to other features of the ad (say, the ad message) and appreciate that the music is not interfering. Similarly, the negative effect of disliked music might be reduced if the music is presented at low Affective components . Emotions (feelings) evoked by music. Related to the evoke emotions (feelings) goal, this element concerns whether feeling states are actually evoked by the music, how 402 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 volume. However, research is required to determine whether this is effective in achieving other advertising objectives. Of course, a favorable attitude toward the amount of attention elicited by ad music might occur if the consumer enjoys and chooses to attend to it. A challenge is to find music that can have this effect on a significant number of consumers in the target market. Attention alone is not sufficient – on balance, the cognitive and affective impacts following from attention must not be negative. And, perhaps above all else, music must not attract attention solely to itself but to the brand and brand message. Depth of processing of music. Despite the claim that music enhances memory of the ad’s content, research evidence is mixed (Kellaris et al., 1993), with some studies showing positive effects (Hoyer et al., 1984; Hunt, 1988; MacInnis and Park, 1991; Olsen, 1995; North et al., 2004b; Roehm, 2001; Wallace, 1991; Wallace, 1994, Experiments 1 and 2; Yalch, 1991), others demonstrating negative results (Galizio and Hendrick, 1972; Haley et al., 1984; Sewall and Sarel, 1986; Wallace, 1994, Experiment 3; Wheatley and Brooker, 1994), and still others yielding neutral findings (Brooker and Wheatley, 1994; Macklin, 1988; Stewart and Furse, 1986; Wallace, 1994, Experiment 4). We speculate that music that does not aid ad memorability fails on one or more of the four criteria for enhancing memory through music outlined above (notably music-message fit), but subsequent research should verify this. In particular, future research exploring the depth of processing component of Aam may help to disentangle these mixed findings. Consider the case of ad music with lyrics containing the ad message. A large body of research on memory for verbal materials indicates that deep or semantic-level processing (e.g. of the meaning of a printed word) leads to better recall than does shallow-level processing of the same material (e.g. the font that the word is presented in). When it comes to the role of music in enhancing memory for ad lyrics, however, deeper is not necessarily better. For instance, a consumer might engage in deep processing of lyrics by focusing on their meaning or shallow processing by focusing on the sung melody. As Wallace (1994) points out, the reason that music sometimes facilitates recall of verbal material is that it draws attention to linked surface properties of both the melody and of the lyrics, such as their corresponding rhythmical properties, line length, intonation patterns, and so on: original music – written, scored, and recorded specifically for the commercial – rather than relying on or adapting existing music, might be defeating their cognitive goals if consumers use cognitive capacity to learn the new music instead of the ad message. Of course, repetition – either within the ad or through multiple exposures to the ad – can promote learning of the music and thus help to achieve recall of ad content. But advertisers should monitor for “wearout.” Burke and Edell (1986) found that Aad declined with repeated exposures, and so it would seem reasonable to suppose that, because music can wear out, it might contribute to a decline in Aad with too much repeated exposure. Similarly, familiar music might have already induced wearout. Indeed, a good deal of research supports the view that listeners prefer music of moderate complexity and that the subjective complexity of a given piece of music decreases with repeated exposure (Hargreaves, 1984; Hargreaves et al., 2006; Tan et al., 2006). Thus, subjectively complex ad music will initially be disliked but become more liked with repeated exposure as it is learned. Ad music that is initially of moderate subjective complexity will be liked at first, but with repeated exposure it will become overly familiar, subjectively simple, and hence disliked. Finally, ad music that starts out as too simple will tend to be disliked and will remain so with repeated exposure. To summarize, music can enhance memory of ad content in lyrics if it helps the consumer focus on surface characteristics of the lyrics and is simple/repetitive/well-learned. However, when the latter applies, the music may be disliked. What should a marketer to do? Research measuring both memory effects and liking (from the music cognition literature, see Peretz et al., 1998) seems to be called for to determine the tradeoffs between – and the ideal combinations of – depth of processing, musical complexity, and repetition. On balance, in the case of ad music with lyrics, it would seem that the best musical stimulus for achieving long-term recall is an original jingle that is simple to learn and that fits the ad message. It should be catchy, memorable, and likeable enough so that listeners will play it back mentally. This will promote rehearsal and cueing of memory associations with ad content, especially if this cuing is enhanced by striking congruent visual and emotional elements. In short, original, somewhat simple but involving music with lyrics that are relevant to the ad message will best enhance message recall. This harks back to the commercial jingles of yesteryear and suggests that the current trend to incorporate the use of new music by promising upstart bands might be misguided. Now consider the case of instrumental music. Segalowitz et al.(2001) suggest that one can distinguish between deepand shallow-level processing of music per se, as opposed to the verbal material contained in lyrics. They propose that in this case, deep-level processing of the “meaning” of the music involves focusing on the aesthetic intentions of the performer. This can be contrasted with processing that focuses on the surface features of the music, such as the individual notes, the timbre of one of the instruments, or the physical appearance of a performer without regard to the aesthetic dimension of the music. Although research is lacking in this area, a reasonable working hypothesis is that memory for the ad music will be enhanced if it is processed at a deep rather than a shallow level, but deep processing of ad music will have the opposite effect on memory for the ad message. Often, focusing on the deep-meaning structures of a text facilitates recall more than focusing on the surface properties. However, when the surface properties are well structured, abundant, and interconnected, and when music or some other mechanism draws attention to the surface properties, then those same properties may facilitate recall [. . .] Furthermore, music, unlike text, may be one stimulus for which listeners are particularly adept at identifying and recognizing surface characteristics (p. 1,482). Surprisingly, some amount of shallow-level processing of both music and text seems to be necessary to reap the memory benefits of presenting the ad message in song! Future research might test this more directly by manipulating listeners’ level of processing of music and lyrics in ad stimuli. A related point, noted earlier, is that music enhances memory for ad content contained in lyrics only if that music is simple, repetitive, or well-learned (Wallace, 1994). Presumably, these are the conditions that make it possible for a consumer to compare the surface properties of music and text, as discussed above. Therefore, advertisers using 403 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 Perceived features of music available for association. As a creative director for a music agency observed, “The music ‘brandscape’ is incredibly cluttered at first glance, but when you try and name the brands who really have a residual value from music, there are very few” (Woods, 2007). Building new music-brand associations is challenging for two reasons. First, such music-brand linkages take time to build, and so repetition is important (e.g. the playing weekly of the William Tell Overture to open The Lone Ranger). Unfortunately, however, repetition of music eventually leads to wearout. Second, the ability to condition such associations is not guaranteed: while some researchers report that consumers can be classically conditioned to prefer a product by pairing it with well-liked music (e.g. music that is perceived as pleasant can create a pleasing feeling toward the brand), others have failed to obtain this effect (e.g. Gorn, 1982; Zander, 2006). Research on music-message fit (Alpert and Alpert, 1991; Kellaris et al., 1993; MacInnis and Park, 1991) suggests that creating new associations between music and brand should be easiest with a strong fit of the music to the message and brand image. Of course, even if new musicbrand associations are not formed, associations between the ad music and other ad content might still build, with the effect that the music becomes a retrieval cue for elements of the ad other than the brand per se. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, if the perceived features of the music are negatively viewed, this obviously creates an undesirable music-brand association. A given consumer in a particular context may react negatively to any number of features of the ad music. Disliking the genre or musical style appears to be a particularly serious risk, since musical style is more important than musical piece in determining listeners’ responses (North and Hargreaves, 1999), musical styles preferences vary widely among individuals and contexts (Hargreaves et al., 2006; Rentfrow and Gosling, 2003), and attitudes toward musical styles are closely tied to personal identity and to lifestyle (North and Hargreaves, 2007a,b,c). In fact, a recently conducted survey which asked respondents about their “most hated” style of music found that negative attitudes toward disliked musical styles are as intense as positive attitudes toward favorite musical styles (Craton et al., 2008). The effect of such musical “pet peaves” on response to ads with music is an important topic for future research. Given the above arguments in favor of including music in advertising summarized at the beginning of this article, such research is needed to help determine whether the potential problem of running music that is liked by most but disliked by some members of the target market is serious enough to suggest using a “sound-of-silence” strategy (Olsen, 1994). Remembered features of music available for association. As with new associations, previously learned associations can work against an advertiser if they are negative (e.g. German military music activating images of Nazis) or conjure up a disfavored or inappropriate brand image or symbolism. Unfortunately, existing associations, be they informational, symbolic, or autobiographical, can be negative for some targeted consumers, even when they are neutral or positive for most consumers. Image suggested by music. Research on the effect of music on brand image associations is lacking (Allan, 2007; Stout and Leckenby, 1988). Such research would be difficult since the formation of brand images through music is a complex process, being a function of musical genre, artist, lyrics, and structural characteristics. Damage to an existing brand image would likely occur if the wrong music is selected or if it is vague enough to suggest different brand images to different people. Music perceived as distinctive or not. To achieve brand distinctiveness, original music would seem to be preferred, all else equal. Unique jingles better achieve distinctiveness than do public domain music or licensed tunes (and, as already noted, if simple and congruent with the message, unique jingles enhance relevant recall). Unfortunately, the same features that make ad music distinctive may in some cases make it subjectively complex for many consumers and, as we have seen, subjectively complex music tends to be disliked. Conversely, a consumer might adopt an unfavorable view of bland, non-distinctive pop music in a commercial because it is too predictable. Advertisers seem to be faced with the challenge of selecting music that is both distinct and optimally (i.e. only moderately) complex. In fact, negative distinctiveness might arise due to any of the musical considerations that could harm a brand as outlined in Table I. Thus, distinction for the sake of being different is insufficient – distinctions are only potentially helpful if they are viewed favorably and meaningfully distinguish the brand. The latter notion points to the importance of music-message fit, which we discuss next. Perceived music-message fit. Music appears to work best when it is an integral part of the selling message (Dunbar, 1990; Kellaris et al., 1993), and an appropriate fit can enhance the brand image (Alpert and Alpert, 1991). Some researchers suggest that music that fits the advertisement enhances recall by priming relevant beliefs about the brand, activating related information in memory and evoking message-congruent thoughts (Kellaris et al., 1993). Direct empirical evidence for this mechanism is limited, however (North et al., 2004b). An inappropriate fit can have a distracting effect (Macklin, 1988). Indeed, perhaps the strongest argument against using music in advertising is that it can serve as a distraction – an attention-grabber that is irrelevant to the message (Brooker and Wheatley, 1994; Macklin, 1988). For instance, Park and Young (1986) found that under high cognitive involvement, preselected popular and liked music was a distraction from the message, lowering response variable scores because it was unrelated to brand-attribute message contents. Park and Young (1986) and MacInnis and Park (1991) suggested and found that low-fit musical stimuli can disrupt high cognitively involved consumers’ efforts to process product information. Shen and Chen (2006) reported that when there was lack of music congruency, Aad was negatively impacted. Similarly, MacInnis and Park (1991), Meyers-Levy and Tybout (1989), and Shen and Chen (2006) all found that low perceived fit triggered negative emotions such as frustration and helplessness, leading to negative Aad. Indeed, some evidence suggests that the absence of music is no worse and often more effective than music that is a poor fit with the brand (Kellaris et al., 1993; North et al., 2004b). Consequently, musical fit is perhaps the most influential of all aspects of the musical stimulus. Although the importance of perceived music-message fit is often acknowledged (Alpert and Alpert, 1991; Dunbar, 1990), surprisingly little empirical research has explored it. Three important challenges remain. One central challenge for both practitioners and researchers is to operationally define “perceived music-message fit” so that it can be employed as a 404 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 dependent variable. Strictly speaking, fit is a subjective, not objective, property of commercial music and varies between individuals depending on the content of their memories (Englis and Pennell, 1994), again suggesting the difficulty of achieving uniform appeal and relevance through music. A second challenge is to systematically identify the musical variables that influence consumers’ perception of fit. Logically, music can convey meaning in two ways that merit further empirical testing: 1 nonverbally by instrumental music; and 2 verbally by lyrics. the fact that a consumer perceives a particular emotional expression in a piece of music does not guarantee that the he/she will experience the same emotion or any emotion (Gabrielsson, 2002; cited in Västfjäll, 2002). Indeed, the cognitive priming (memories, associations, or thoughts) caused by the perception of emotion in music may be as important as the feelings that are evoked (North et al., 2004a,b). Mood induced by music. Advertisers who are unaware of the mood evoked by music could inadvertently induce the wrong mood – one that is either unfavorable or inappropriate to the brand message and image. This is possible since the effect of music on mood as a response variable has been shown to depend on mood as an antecedent condition, suggesting that different consumers will have different mood reactions to the same musical piece as might the same consumer on different occasions. Interestingly, Wheeler (1985) found that for people in good moods, music they enjoy will not make them feel better, but music they dislike will make them feel worse. However, people in bad moods will not feel worse if they hear music they dislike, but they might feel better if they hear music they enjoy. Research must demonstrate that most listeners will perceive a similar and desirable mood from a commercial’s music. Emotional memories activated by music. Even the most pleasant music can evoke negative emotional memories for some (e.g. a wedding processional might bring back memories of a bad marriage for a divorced person). Also, Englis and Pennell (1994) note that fans might resent advertisers who use “their” music commercially, perhaps because they do not wish for its positive associations to be sullied by commercial associations. This possibility should be tested empirically. It argues for the use of original music, as has the discussion of several other Aam components above. Emotional arousal response to music. Advertisers must be careful to select music that creates a desirable level of arousal. Music that is either overly or insufficiently arousing for a particular consumer in a specific context will be regarded unfavorably. A good rule of thumb might be to match or gauge the level of stimulation evoked by the music with that of the programming content that precedes it. Since the latter is often (though not always) chosen by the consumer, this reduces the risk of unfavorable response. Hedonic experience. A major premise of psychologists has been that music produces a pleasurable sensation (Stout and Rust, 1986). However, music that is disfavored for any of the above reasons could evoke feelings of displeasure and perhaps thereby increase counter argumentation. Unfortunately, as already discussed, musical tastes and distastes vary widely (Rentfrow and Gosling, 2003). This leads to our second general managerial challenge. Nonverbal transfer of meaning by instrumental music can occur through conveying images, thoughts, feelings (Kellaris et al., 1993), and associations (Zhu and Meyers-Levy, 2005). Hence, energetic music tends to evoke thoughts related to excited frivolity, while sedate music recalls thoughts about calm, contemplative activity (Gabrielsson and Lindstrom, 2001). Alpert et al. (2003) found that the use of music congruent with the symbolic meaning of product purchase (such as to convey status) enhanced purchase probability. Lyrics in ad music convey meaning by being relevant to a commercial’s message (MacInnis and Park, 1991). For example, a Kingsford charcoal commercial used a tune called “Grillin’ and Chillin”, conveying a mood of a lazy summer barbecue in the afternoon, creating a desire for kicking back (Ask the Ad Team, 2009). Or, the romantic, nostalgic song “I’ll be Seeing You” could be effective as background for an FTD florist commercial (Alpert and Alpert, 1991). A third challenge for future research is to determine the conditions under which high (low) music-message fit has its beneficial (negative) effects. Some work suggests that fit music is especially important for high cognitive-involvement consumers because it enhances and guides their motivated thinking about the ad message music, such as happens using sophisticated classical music in a perfume commercial (MacInnis and Park, 1991). According to this view, high fit may be less effective for low-involvement consumers, whose responses are primarily affective. However, findings to date on this topic are mixed. First, sometimes congruity is also important for low involvement consumers, and in some cases incongruity assists memory, perhaps because it increases liking for the ad (North et al., 2004b). Second, incongruity can sometimes aid learning. Srull and Lichtenstein (1985) suggested, and Heckler and Childers (1992) empirically verified that an incongruity of information causes highly involved audience members to process the message with more cognitive effort. Furthermore, music with an inappropriate fit that interferes with message recall and other cognitive processes can enhance the affective state through mechanisms such as mood elevation and affect transfer (Kellaris et al., 1993). Finally, we suggest that this element of Aam probably influences each of the other elements and thus has the potential to mitigate many of the potential pitfalls in using advertising music. We believe that understanding of music in advertising can be significantly advanced through programmatic research investigating the issues discussed above. Achieving universal “high Aam” is unlikely Allan (2007) concluded that, while “the research suggests that music is more likely to positively than negatively affect the consumer’s response to your advertising [. . .] the type of music in particular, must be carefully chosen with the target audience and the desired outcome driving the selection” (p. 27). The numerous potential pitfalls listed above suggest that in so saying, Allan (2007) was too bullish on music in commercials. Achieving universal appeal within any particular target audience is challenging. Moreover, since there is always some Affective components Emotions (feelings) evoked by music. Care must be taken as a given piece of music can arouse different emotional responses both between individuals and for the same individual at different times (Sloboda, 2005). In addition, 405 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 degree of heterogeneity within a target market, music that appeals to most target market members might nonetheless turn off a distinct minority of those audience members. In fact, as noted for several reasons above, music that is effective in a particular commercial in a given listening situation for a given member of the target market might be ineffectual for that same consumer in a different context or advertisement. Herein lies a major problem: music can help target a particular audience. Just as radio stations pursue a particular demographic and lifestyle group through musical genres ranging from Top 40, Urban, and Adult Contemporary to Christian, Tropical Latin, and Active Rock (America’s Music Charts Powered by Media Base, 2008), so can a commercial’s music attract and appeal to a particular target audience. Nonetheless, target market members might to varying degrees differ in their music preferences. Sociologist Herbert Gans’s research demonstrates great heterogeneity regarding music preferences (Fox and Wince, 1975), and “popular music is arguably one of the most polarizing forms of mass communication” (Allan, 2006, p. 435). Despite the useful purposes that music in advertising can serve, not all music garnishes are created equal. In light of the increased fractionalization of the musical marketplace into niches (e.g. rock and roll charts now feature at least four genres: rock, active rock, adult rock, and alternative (http://a mericasmusiccharts.com)), as well as the recent trend to blend different musical genres, such as fusing active rock with hip hop (www.snsmix.com) or with country music, or blending folk, rock, bluegrass, R&B, blues, pop, and “outlaw” country into so-called Americana music, the likelihood of a widespread, strong favorable response to any particular musical stimulus is vanishingly small. On the other hand, music’s potential to repel a significant number of consumers – to elicit disgust by many, while perhaps appealing to a plurality or slim majority – is significant. For example, casual observation and survey data show that while rap music has a significant following, it is also repulsive to many people (Craton et al., 2008; North and Hargreaves, 2004a). Consequently, marketers employ music stimuli at their peril because music used in a commercial that appeals to a majority of target audience members could lead to negative cognitive or affective outcomes for many targeted consumers. Given all of the possible causes of negative consumer response to music, a favorable Aam among most target audience members is very challenging to achieve when foreground music is used in a TV or radio commercial, especially when musicmessage fit is lacking. The watchword for advertisers: be very cautious, and be sure to pretest consumer cognitive and affective responses to not just the ad itself, but also to the ad’s music, taking into consideration both the findings and the limitations of the research conducted to date. Also important to determine is the relative importance of music visà-vis other factors affecting Aad and how this varies with the foreground versus background role of music as well as the use versus nonuse of lyrics and the extent of musicmessage fit. In fact, most advertising research has focused only on music in a background role (e.g. instrumental music); more should be learned about foreground music (e.g. the contribution of a jingle’s lyrics). And, given that there are multiple cognitive and affective musical responses, some of which might be positive while others are negative, it would be instructive to learn how these various responses amplify or counterbalance one another. We are not the first to suggest that music might not be appropriate in all advertising situations (Hunt, 1988), and that music might in certain cases be less appropriate than silence (Olsen, 1994). Indeed, at this point, one might be tempted to conclude that the safest strategy is to refrain from incorporating music into a commercial campaign altogether. We believe the following observation serves as a more fitting conclusion: “Certainly, it is easier to align a brand with music badly – or at least ineffectually – th than to do it well . . . ” (Woods, 2007). Advertiser: Beware! And, as David Ogilvy famously cautioned, “The most important word in the vocabulary of advertising is test” (Ogilvy, 1963, p. 86). Consumer response to music is too idiosyncratic and unpredictable not to do so. References Allan, D. (2005), “An essay on popular music in advertising and popular music: bankruptcy of culture or marriage of art and commerce”, Advertising & Society, Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 434-44. Allan, D. (2006), “Effects of popular music on attention and memory in advertising”, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 46 No. 4, pp. 1-11. Allan, D. (2007), “Sound advertising: a review of the experimental evidence on the effects of music in commercials on attention, memory, attitudes, and purchase intention”, Journal of Media Psychology, Vol. 12 No. 3, available at: www.caltatela.edu/faculty/sfischo Allen, C.T. and Madden, T.J. (1985), “A closer look at classical conditioning”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 12 No. 3, pp. 301-15. Alpert, J.I. and Alpert, M.I. (1989), “Background music as an influence in consumer mood and advertising responses”, in Srull, T.K. (Ed.), Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 16, Association for Consumer Research, Provo, UT, pp. 485-91. Alpert, J.I. and Alpert, M.I. (1990), “Music influences on mood and purchase intentions”, Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 7 No. 2, pp. 109-33. Alpert, J.I. and Alpert, M.I. (1991), “Contributions from a musical perspective on advertising and consumer behavior”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 18, pp. 232-7. Alpert, M.I., Alpert, J.I. and Maltz, E.N. (2003), “Purchase occasion influence on the role of music in advertising”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 58 No. 3, pp. 369-76. America’s Music Charts Powered by Media Base (2008), available at http://americasmusiccharts.com (accessed May 19, 2008 and July 10, 2009). Ask the Ad Team (2009), “August 10, 3B”, USA Today. Babin, L.A. and Burns, A.C. (1997), “Effects of print ad pictures and copy containing instructions to imagine on mental imagery that mediates attitudes”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 26, Fall, pp. 33-44. Bartlett, J.C. and Snelus, P. (1980), “Lifespan memory for popular songs”, American Journal of Psychology, Vol. 93 No. 3, pp. 551-60. Batra, R. and Ray, L.L. (1983), “Advertising situations: the implications of differential involvement and accompanying affect responses”, in Harris, R.J. (Ed.), Information Processing Research in Advertising, Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 127-51. 406 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 Batra, R. and Ray, M.L. (1986), “Affective responses mediating acceptance of advertising”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 234-49. Biehal, G., Stephens, D. and Curlo, E. (1992), “Attitude toward the ad and brand choice”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 21 No. 3, pp. 19-36. Bower, G.H. and Bolton, L.S. (1969), “Why are rhymes easy to learn?”, Journal of Experimental Psychology, Vol. 82 No. 3, pp. 453-61. Brooker, G. and Wheatley, J.J. (1994), “Music and radio advertising: effects of tempo and placement”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 21, pp. 286-90. Brown, S.P. and Stayman, D. (1992), “Antecedents and consequences of attitude toward the ad: a meta-analysis”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 19, June, pp. 34-51. Bruner, G.C. (1990), “Music, mood, and marketing”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54, pp. 94-104. Burke, M.C. and Edell, J.A. (1986), “Ad reactions over time: capturing changes in the real world”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 13, June, pp. 114-8. Burke, M.C. and Edell, J.A. (1989), “The impact of feelings on ad-based affect and cognition”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 26, February, pp. 69-83. Chebat, J., Chebat, C.G. and Vaillant, D. (2001), “Environmental background music and in-store selling”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 54 No. 2, pp. 115-23. Clow, K.E. and Baack, D. (2003), Integrated Advertising, Promotion, and Marketing Communications, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. Craik, F.I.M. and Lockhart, R.S. (1972), “Levels of processing: a framework for memory research”, Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, Vol. 11 No. 6, pp. 671-84. Craik, F.I.M. and Tulving, E. (1975), “Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory”, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, Vol. 104 No. 3, pp. 268-94. Craton, L.G., Poirier, C.P., Hayden, E., Schur, A., Gunnery, S.D., Zellers, H.J. and Merola, E.E. (2008), “The development of musical taste and distaste”, poster submitted for presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Eastern Psychological Association, Boston, MA, March 13-16. Dunbar, D.S. (1990), “Music and advertising”, International Journal of Advertising, Vol. 9 No. 3, pp. 197-203. Englis, B.G. and Pennell, G.E. (1994), “This note’s for you . . .: negative effects of the commercial use of popular music”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 21, p. 97. Finnäs, L. (1989), “How can musical preferences be modified? A research review”, Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, Vol. 102, pp. 1-58. Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975), Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA. Fox, W.S. and Wince, M.H. (1975), “Musical taste cultures and taste publics”, Youth and Society, Vol. 7 No. 2, pp. 198-224. Fried, R. and Berkowitz, L. (1979), “Music hath charms . . . and can influence helpfulness”, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 199-208. Gabrielsson, A. and Lindstrom, S. (2001), “The influence of musical structure on emotional expression”, in Juslin, P.N. and Sloboda, J.A. (Eds), Music and Emotion: Theory and Research, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 223-48. Galizio, M. and Hendrick, C. (1972), “Effect of musical accompaniment on attitude: the guitar as a prop for persuasion”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 2 No. 4, pp. 350-9. Gardner, M.P. (1985a), “Does attitude toward the ad affect brand attitude under a brand evaluation set?”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 192-8. Gardner, M.P. (1985b), “Mood states and consumer behavior: a critical review”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 12 No. 3, pp. 281-300. Gorn, G.J. (1982), “The effects of music in advertising on choice behavior: a classical conditioning approach”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 46 No. 1, pp. 94-101. Gresham, L.G. and Shimp, T.A. (1985), “Attitude toward the advertisement and brand attitudes: a classical conditioning perspective”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 10-17. Haley, R.I., Richardson, J. and Baldwin, B.M. (1984), “The effects of nonverbal communications in television advertising”, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 24 No. 4, pp. 11-18. Hargreaves, D.J. (1984), “The effects of repetition on liking for music”, Journal of Research in Music Education, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 34-47. Hargreaves, D.J., North, A.C. and Tarrant, M. (2006), “Musical preference and taste in childhood and adolescence”, in McPherson, G.E. (Ed.), The Child as Musician: Musical Development from Conception to Adolescence, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Hecker, S. (1984), “Music for advertising effect”, Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 1 Nos 3/4, pp. 3-8. Heckler, S. and Childers, T. (1992), “The role of expectancy and relevancy in memory for verbal and visual information: what is incongruency?”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 475-92. Homer, P.M. (1990), “The mediating role of attitude toward the ad: some additional evidence”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 78-86. Howard, T. (2008), “Out: jingles. In: cool songs”, USA Today, June 16, 1B, 3B. Hoyer, W.D., Srivastava, R.K. and Jacoby, J. (1984), “Sources of miscomprehension in television advertising”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 17-26. Hunt, 1988 (1988), “An experimental study of the effect of music on radio commercial performance”, Proceedings of the Southern Marketing Association, pp. 37-40. Isen, A.M., Shalker, T., Clark, M. and Karp, L. (1978), “Affect, accessibility of material in memory and behavior: a cognitive loop?”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 36 No. 1, pp. 1-12. Juslin, P.N. and Sloboda, J.A. (2001), Music and Emotion: Theory and Research, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Juslin, P.N. and Västfjäll, D. (2008), “Emotional responses to music: the need to consider underlying mechanisms”, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, Vol. 31, pp. 597-8. Kassarjian, H.H. (1971), “Personality and consumer behavior: a review”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 409-18. Kellaris, J.J. and Cox, A.D. (1989), “The effects of background music in advertising: a reassessment”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 113-8. 407 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 Kellaris, J.J. and Kent, R.J. (1991), “Exploring tempo and modality effects, on consumer responses to music”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 18, pp. 243-8. Kellaris, J.J. and Kent, R.J. (2001), “An exploratory investigation of responses elicited by music varying in tempo, tonality, and texture”, Journal of Consumer Psychology, Vol. 2 No. 4, pp. 381-401. Kellaris, J.J. and Mantel, S.P. (1996), “Shaping time perceptions with background music: the effect of congruity and arousal on estimates of ad durations”, Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 13 No. 5, pp. 501-15. Kellaris, J.J. and Rice, R.C. (1993), “The influence of tempo, loudness, and gender on responses to music”, Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 15-29. Kellaris, J.J., Cox, A.D. and Cox, D. (1993), “The effect of background music on ad processing: a contingency explanation”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 57 No. 4, pp. 114-25. Lee, Y.H. and Mason, C. (1999), “Responses to information incongruency in advertising: the role of expectancy, relevancy, and humor”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 26, September, pp. 156-69. Lutz, R.J. (1985), “Affective and cognitive antecedents of attitude toward the ad: a conceptual framework”, in Alwitt, L.F. and Mitchell, A.A (Eds), Psychological Processes and Advertising Effects: Theory, Research and Application, Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 45-63. McEwen, J. and Leavitt, C. (1976), “A way to describe TV commercials”, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 16, pp. 35-9. McQuarrie, E.F. and Mick, D.G. (2003), “Visual and verbal rhetorical figures under directed processing versus incidental exposure to advertising”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 29, March, pp. 579-87. Machleit, K.A. and Wilson, D.R. (1988), “Emotional feelings and attitude toward the advertisement: the roles of brand familiarity and repetition”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 27-35. MacInnis, D.J. and Park, C.W. (1991), “The differential role of characteristics of music on high- and low-involvement consumers’ processing of ads”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 161-73. MacKenzie, S.B. and Lutz, R.J. (1989), “An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretest context”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 53, April, pp. 48-65. MacKenzie, S.B., Lutz, R.J. and Belch, G.B. (1986), “The role of attitude toward the ad as a mediator of advertising effectiveness: a test of competing explanations”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 23 No. 2, pp. 130-43. Macklin, M.C. (1988), “The relationship between music in advertising and children’s responses: an experimental investigation”, in Hecker, S. and Stewart, D.W. (Eds), Nonverbal Communication in Advertising, Lexington Books, Lexington, MA, pp. 225-45. Meyers-Levy, J. and Tybout, A. (1989), “Schema congruity as a basis for product evaluation”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 16, pp. 39-54. Middlestadt, S.E., Fishbein, M. and Chan, D.K.-S. (1994), “The effect of music on brand attitudes: affect- or beliefbased change?”, in Clark, E.M., Brock, T.C. and Stewart, D.W. (Eds), Attention, Attitude, and Affect in Response to Advertising, Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 149-67. Mitchell, A.A. (1986), “The effect of verbal and visual components of advertisements on brand attitudes and attitude toward the advertisement”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 12-24. Mitchell, A.A. and Olson, J.C. (1981), “Are product attribute beliefs the only mediator of advertising effects on brand attitude?”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18 No. 3, pp. 318-32. Moore, D.L. and Hutchinson, J.W. (1985), “The influence of affective reactions to advertising: direct and indirect mechanisms of attitude changes”, in Alwitt, L.F. and Mitchell, A.A. (Eds), Psychological Processes and Advertising Effects: Theory, Research and Application, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 65-87. Morris, J.D. and Boone, M.A. (1998), “The effects of music on emotional response, brand attitude, and purchase intent in an emotional advertising condition”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 25, pp. 518-26. Muehling, D.D. and Laczniak, R.N. (1988), “Advertising’s immediate and delayed influence on brand attitudes: considerations across message involvement levels”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 17 No. 4, pp. 23-34. North, A.C. and Hargreaves, D.J. (1996), “The effects of music on responses to a dining area”, Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 55-64. North, A.C. and Hargreaves, D.J. (1997), “Music and consumer behavior”, in Hargreaves, D.J. and North, A.C. (Eds), The Social Psychology of Music, Oxford University Press, Oxford. North, A.C. and Hargreaves, D.J. (1999), “Music and adolescent identity”, Music Education Research, Vol. 1, pp. 75-92. North, A.C. and Hargreaves, D.J. (2007a), “Lifestyle correlates of musical preference: 1. Relationships, living arrangements, beliefs, and crime”, Psychology of Music, Vol. 35 No. 1, pp. 58-87. North, A.C. and Hargreaves, D.J. (2007b), “Lifestyle correlates of musical preference: 2. Media, leisure time, and music”, Psychology of Music, Vol. 35 No. 2, pp. 179-200. North, A.C. and Hargreaves, D.J. (2007c), “Lifestyle correlates of musical preference: 3. Travel, money education, employment, and health”, Psychology of Music, Vol. 35 No. 3, pp. 473-98. North, A.C. and Hargreaves, D.J. (2008), The Social and Applied Psychology of Music, Oxford University Press, Oxford. North, A.C., Hargreaves, D.J. and Hargreaves, J.J. (2004a), “Uses of music in everyday life”, Music Perception, Vol. 22, pp. 41-77. North, A.C., Hargreaves, D.J., McKenzie, L.C. and Law, R. (2004b), “The effects of musical and voice ‘fit’ on responses to advertisements”, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 34, pp. 1675-708. Oakes, S. (2007), “Evaluating empirical research into music in advertising: a congruity perspective”, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 47, pp. 38-50. Ogilvy, D. (1963), Confessions of an Advertising Man, Longman, London. Ogilvy, D. (1984), Ogilvy on Advertising, Vintage Books, New York, NY. Ogilvy, D. and Raphaelson, J.R. (1982), “Research on advertising techniques that work – and don’t work”, Harvard Business Review, pp. 14-16, July-August. 408 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 Olsen, G.D. (1994), “The sounds of silence: functions and use of silence in television advertising”, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 34 No. 5, pp. 89-95. Olsen, G.D. (1995), “Creating the contrast: the influence of silence and background music on recall and attribute importance”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 14 No. 4, pp. 29-44. Olsen, G.D. (2002), “Salient stimuli in advertising: the effect of contrast interval length and type on recall”, Journal of Experimental Psychology, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 168-79. Onkvisit, S. and Shaw, J. (1987), “Self-concept and image congruence: some research and managerial implications”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 4 No. 1, pp. 13-23. Park, C.W. and Young, S.M. (1986), “Consumer response to television commercials: the impact of involvement and background music on brand attitude formation”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 11-24. Peretz, I., Gaudreau, D. and Bonnel, A.-M. (1998), “Exposure effects on music preference and recognition”, Memory & Cognition, Vol. 26 No. 5, pp. 884-902. Pitt, L.F. and Abratt, R. (1988), “Music in advertisements for unmentionable products – a classical conditioning experiment”, International Journal of Advertising, Vol. 7 No. 2, pp. 130-7. Pope, N.K.L., Voges, K.E. and Brown, M.R. (2004), “The effect of provocation in the form of mild erotica on attitude to the ad and corporate image”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 33 No. 1, pp. 69-82. Rentfrow, P.J. and Gosling, S.D. (2003), “The do-re-mi’s of everyday life: the structure and personality correlates of music preferences”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 84, pp. 1236-56. Rentfrow, P.J. and Gosling, S.D. (2006), “Message in a ballad: the role of music preferences in interpersonal perception”, Psychological Science, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 236-42. Roehm, M.L. (2001), “Instrumental vs vocal versions of popular music in advertising”, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 41 No. 3, pp. 49-58. Rossiter, J.R. and Percy, L. (1991), “Emotions and motivations in advertising”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 18, pp. 100-11. Rubin, D.C. (1977), “Very long-term memory for prose and verse”, Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, Vol. 16 No. 5, pp. 611-21. Scott, L.M. (1990), “Understanding jingles and needledrop: a rhetorical approach to music in advertising”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 223-36. Segalowitz, N., Cohen, P., Chan, A. and Prieur, T. (2001), “Musical recall memory: contributions of elaboration and depth of processing”, Pscyhology of Music, Vol. 29 No. 2, pp. 139-48. Sewall, M.A. and Sarel, D. (1986), “Characteristics of radio commercials and their recall effectiveness”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 50 No. 1, pp. 52-60. Shen, Y.-C. and Chen, T.-C. (2006), “When east meets west: the effect of cultural tone congruity in ad music and message on consumer ad memory and attitude”, International Journal of Advertising, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 51-70. Shimp, T.A. (1981), “Attitude toward the ad as a mediator of consumer brand choice”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 10, pp. 9-15. Simpkins, J.D. and Smith, J.A. (1974), “Effects of music on source evaluations”, Journal of Broadcasting, Vol. 18, Summer, pp. 361-7. Sirgy, M.J. (1982), “Self-concept in consumer behavior: a critical review”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 9 No. 3, pp. 287-300. Sloboda, J.A. (2005), Exploring the Musical Mind, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Sloboda, J.A., O’Neill, S.A. and Ivaldi, A. (2001), “Functions of music in everyday life: an exploratory study using the experience sampling method”, Musicae Scientiae, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 9-32. Srull, T. and Lichtenstein, M. (1985), “Associate storage and retrieval processes in person memory”, Journal of Experimental Psychology, Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 316-45. Stayman, D.M. and Aaker, D.A. (1988), “Are all the effects of ad-induced feelings mediated by (attitude toward the ad)?”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 368-73. Stewart, D.W. and Furse, D.H. (1986), Effective Television Advertising: A Study of 1,000 Commercials, Lexington Books, Lexington, MA. Stewart, D.W., Farmer, K.M. and Stannard, C.I. (1990), “Music as a recognition cue in advertising-tracking studies”, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 30 No. 4, pp. 39-48. Stout, P. and Leckenby, J.D. (1988), “Let the music play: music as a nonverbal element in TV commercials”, in Hecker, S. and Stewart, D.W. (Eds), Nonverbal Communication in Advertising, Lexington Books/D.C. Heath, Lexington, MA, pp. 207-23. Stout, P.A. and Rust, R.T. (1986), “The effect of music on emotional response to advertising”, in Larkin, E.F. (Ed.), Proceedings of the 1986 Conference of the American Academy of Advertising, School of Journalism, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, pp. R82-5. Stout, P.A., Leckenby, J.D. and Hecker, S. (1990), “Viewer reactions to music in television commercials”, Journalism Quarterly, Vol. 67, pp. 887-98. Sutherland, M. and Sylvester, A.K. (2000), Advertising and the Mind of the Consumer, 2nd ed., Allen & Unwin, St Leonards. Tan, S.L., Spackman, P. and Peaslee, C.L. (2006), “The effects of repeated exposure on liking and judgments of musical unity and patchwork compositions”, Music Perception, Vol. 23 No. 5, pp. 407-21. Västfjäll, D. (2002), “A review of the musical mood induction procedure”, Musicae Scientae (Special Issue 2001-2002), pp. 173-211. Wallace, W.T. (1991), “Jingles in advertisements: can they improve recall?”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 18, pp. 239-42. Wallace, W.T. (1994), “Memory for music: effect of melody on recall of text”, Journal of Experimental Psychology, Vol. 20 No. 6, pp. 1471-85. Wells, W.D. and Beard, A.D. (1973), “Personality and consumer behavior”, in Ward, S. and Robertson, T.S. (Eds), Consumer Behavior: Theoretical Sources, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, pp. 141-99. Wheatley, J.J. and Brooker, G. (1994), “Music and spokesperson effects on recall and cognitive response to a radio advertisement”, in Clark, E.M. and Brooker, G. (Eds), Attention, Attitude, and Affect in Response to Advertising, Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillside, NJ, pp. 189-204. 409 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 Executive summary and implications for managers and executives Wheeler, B.L. (1985), “Relationship of personal characteristics to mood and enjoyment after hearing live and recorded music and to musical taste”, Psychology of Music, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 81-92. Woods, A. (2007), “Getting in on the act. With music and brands working more closely than ever, agencies want a piece of the action”, Media Week, November 6. Yalch, R.F. (1991), “Memory in a jingle jungle: music as a mnemonic device in communicating advertising slogans”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 76 No. 2, pp. 268-75. Zander, M.F. (2006), “Musical influences in advertising: how music modifies first impressions of product endorsers and brands”, Psychology of Music, Vol. 34 No. 4, pp. 465-80. Zanna, M.P., Kiesler, C.A. and Pilkonis, P.A. (1970), “Positive and negative attitudinal affect established by classical conditioning”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 14 No. 4, pp. 321-8. Zhu, R. and Meyers-Levy, J. (2005), “Distinguishing between meanings of music: when background music affects product perceptions”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 42 No. 3, pp. 333-45. This summary has been provided to allow managers and executives a rapid appreciation of the content of the article. Those with a particular interest in the topic covered may then read the article in toto to take advantage of the more comprehensive description of the research undertaken and its results to get the full benefit of the material present. Music today plays a significant part in most people’s everyday lives and much of the exposure is involuntary. Radio and television commercials are responsible for much involuntary listening. Many studies view music in advertising positively and believe that it increases the effectiveness of a commercial. Others are less complimentary, arguing that using popular music in advertising is culturally damaging. Despite such contradictions, companies have kept faith in the musical aspect of their ads and continue to back up this belief with huge resources. Craton and Lantos argue that some important limitations have risen as a result of studies into advertising music. There is the widespread assumption that virtually any product advertisement is enriched by the presence of music. Much empirical evidence casts doubt on this and suggests that music can have a neutral or detrimental effect as well as a positive one. Some observers concede that reasons for this varied impact are not readily apparent and the scarcity of research into this issue is another limitation. Its importance is emphasized by the existing belief in some quarters that aversion to music in a commercial can have a negative effect on advertiser and brand credibility. The final limitation concerns tendency in the literature to regard advertising music as an “affective stimulus” only. This view fails to consider its aptitude to engage people cognitively as well. It has been noted though that music can distract consumers and impede their processing of the brand message contained in the ad. Consumers who respond negatively to a commercial could perceive the ad music as inappropriate, unsuitable for purpose or lacking in congruence with brand message. They might also dislike the musician or find the tune annoying or boring. Some argue that music can help achieve cognitive effects that are perceived as advertising objectives. They can: . attract attention with music that is inspiring or interesting; . enhance the memory of ad content – it is claimed that music aids associations and recall; . create new associations between music and brand; . recall previous associations with such as location, time period or environment; . help develop a brand image, for instance, through use of a particular music genre; . differentiate the brand using distinctive music; and . reinforce the ad message through fit between music, ad meaning and brand image. Further reading Scratch ‘N Sniff (2009), “Station affiliates”, available at: www.snsmix.com (accessed July 10, 2009). About the authors Lincoln G. Craton is Associate Professor of Psychology, Stonehill College, Easton, Massachusetts, USA. A developmental psychologist, Craton has previously published in and served as reviewer for such journals as Child Development, Developmental Psychology, Evolutionary Psychology, and Perception and Psychophysics. His current research interests include own-age bias in face recognition and topics in music perception/cognition, particularly the cognitive basis of musical preferences and explicit and implicit knowledge of harmony in listeners without musical training. He enjoys playing jazz guitar with his trio, Linc Cray and the CrayTones. Geoffrey P. Lantos is Professor of Business Administration and Marketing Major Program Director, Stonehill College, Easton, Massachusetts, USA. Lantos is the author of Consumer Behavior in Action: Real-life Applications for Marketing Managers (2011, M.E. Sharpe). He has previously published in such journals as Journal of Consumer Marketing, Strategic Direction, Journal of Biblical Integration in Business, Marketing Education Review, Journal of Product & Brand Management, Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, and Journal of the Market Research Society. Lantos serves as Book Reviews Editor at Journal of Consumer Marketing and Journal of Product & Brand Management and is on several editorial review boards. His research interests include ethics, corporate social responsibility, and educational pedagogy. Geoffrey P. Lantos is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: glantos@stonehill.edu Research has likewise identified five elements of the affective responses that are also considered advertising objectives: 1 evoke feelings that might prompt positive affect towards the ad and lead to purchase; 2 create a mood in the commercial that subsequently becomes associated with the brand; 3 tap into positive or negative emotion-laden memories; 410 4 5 Attitude toward the advertising music Journal of Consumer Marketing Lincoln G. Craton and Geoffrey P. Lantos Volume 28 · Number 6 · 2011 · 396 –411 influence the intensity of emotions which are evoked; and provide a positive hedonic experience reflecting such as feelings and fantasy. Much attention has been afforded to attitude, which is widely considered a useful predictor of future behavior. In this context, attitude toward an advertisement reflects an individual’s evaluation and/or emotional response to the stimulus. Attitude might have the greatest impact on future purchase intentions immediately following exposure to the ad. But in comparison to attitude towards the brand and towards advertising in general, this effect will probably be less enduring. Different researchers claim that attitude towards an ad mediates attitude towards the brand and this is supported by empirical evidence. The impact of music on attitude towards the brand has been widely addressed. But the few studies exploring how ad music impacts on attitude towards the ad have produced inconclusive findings. Attitude towards ad music incorporates cognitive and affective components, each of which corresponds with one of the advertising objects detailed earlier. Cognitive elements are: . level and persistence of attention to music – it is important to know which aspects of the music entice the consumer; . musical components the consumer will use to create brand associations; . remembered features of music in these associations and whether they are common or idiosyncratic; . image suggested by music or the music’s perceived personality; . whether music is distinctive enough to differentiate the brand; and . fit level between music and message, with high fit prompting a more favorable attitude. . . . . . . . . Affective components include: . feelings evoked by music and their intensity; . mood induced by music and its accord with the brand’s message; . emotional memories activated by music and how the consumer views them; . whether emotional arousal is changed positively or negatively following exposure to ad music; and . how pleasant or unpleasant the consumer finds ad music. fits the ad message could best facilitate long-term recall. Repetition within the ad or through multiple exposures can help reinforce the ad message. Overkill can produce a negative effect though. With instrumental music, advertisers should aim to build music-brand associations. This takes time and repetition, which risks overkill. It can also be difficult to “condition” consumers to these associations. Musical style is important but preferences in this respect widely differ between individuals and contexts. Be aware that previously learned associations might be negative for some consumers within a target group. Note that choosing inappropriate music could harm a brand’s image or suggest different ones. Try to positively differentiate the brand through music containing the right blend of distinctiveness and complexity. Recognize the crucial importance of music-ad fit and that fit is subjective. Marketers might ascertain which musical variables most determine consumer perception of fit and identify conditions where high or low fit is most beneficial or harmful. This component of attitude towards advertising music arguably influences all other elements in the construct. Realize that emotional responses to the same music can vary between individuals and at different times for the same person. The same sentiments apply to mood. Understand that emotional memories are idiosyncratic and even pleasant music can evoke negative or painful recollections for some people. This substantiates the argument for using original music rather than established tunes. Select music that prompts an optimum state of arousal. Too much or too little arousal for certain people in certain contexts will be viewed negatively. Various authors note the difficulty of creating universal appeal through music. Although the right music can help target a particular audience, some heterogeneity will always prevail within each segment. The number of musical genres is increasing further through hybrids of different types, making it even more difficult to achieve the desired widespread response. Caution is therefore essential and marketers should thoroughly test out consumer response to both ad and ad music. Tests might consider foreground and background music with and without lyrics, and how it relates to other factors that influence attitude towards the advertisement. Further examination of relationships between the various cognitive and affective musical responses is additionally recommended. The authors suggest that marketers should pay close attention to the cognitive and affective components contained within the attitude to ad music construct. In their opinion, advertisers should: . Secure an appropriate level of consumer attention with music that attracts attention to ad message and brand as well as itself. . Aim for on optimum blend of depth of processing, musical complexity and repetition. For ad music containing lyrics, using an original yet simple jingle that (A précis of the article “Attitude toward the advertising music: an overlooked potential pitfall in commercials”. Supplied by Marketing Consultants for Emerald.) To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints 411 View publication stats