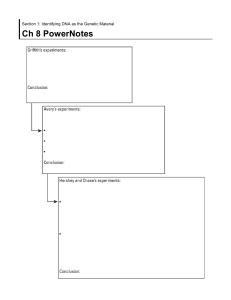

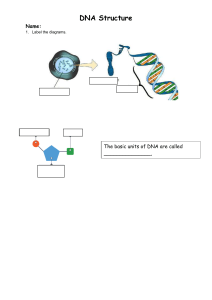

Chapter 13: The Molecular Basis of Inheritance Pages 245-248 Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) DNA is the genetic material that is transmitted from one generation to the next and encodes the blueprints that direct the control of biochemical, anatomical, physiological, and behavioral traits of an organism. A strand of DNA is made up of nucleotide monomers, which consist of a pentose (five carbon sugar), a phosphate group, and a nitrogenous base (either adenine, thymine, cytosine, or guanine) It is autonomously copied in the process of DNA replication. This process allows for genetic inheritance Hereditary information is encoded in the chemical language of DNA and is reproduced in all cells of the body. The Double-Helical Model of DNA In April of 1953, scientists James Watson and Francis Crick proposed the new, double-helical DNA model. It furthered the work of Mendel and Morgan by proving that genes (and chromosomes) are made up of DNA. The Search for the Genetic Material: Scientific Inquiry Thomas Hunt Morgan and his team discovered that genes exist as parts of chromosomes, and they thought that genetic material consisted of DNA and proteins. Many scientists thought chromosomes were made of proteins because proteins were known to have a wide variety of shapes and functions, which made sense given the wide array of heritable factors. Less was known about nucleotides, and many were skeptical that such a uniform molecule could hold genes coding for everything in an organism. Evidence That DNA Can Transform Bacteria The role of DNA in heredity was first worked out while studying the bacteria and the viruses that infected experimental organisms. The microorganisms had simpler genetic information than any previous, genetic experimental subject. In 1928, Frederick Griffith was experimenting with the bacterium, Streptococcus pneumoniae, that causes pneumonia in mammals, to develop a vaccine. He had two strains, one pathogenic (which he killed with heat), and one nonpathogenic. Griffith mixed the strains together, he discovered that some of the living, nonpathogenic cells had become infectious. This process of a change in genotype and phenotype due to external assimilation of DNA by cells is known as transformation. Evidence That Viral DNA Can Program Cells ● Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase started experiments to show that DNA is the genetic material of a bacteriophage know as T2 ○ T2 infects E. coli ○ Bacteriophages ■ Viruses that infect bacteria ■ Not much more than DNA surrounded by a protein casing ■ Multiply by infecting bacteria and hijacking the metabolic system ● Hershey and Chase’s experiment labeled the proteins and DNA with different radioactive markers. They then let them infect E. Coli cells and spun the mixture in a centrifuge to remove the proteins from the outside. ○ Seeing that the DNA was left in the cell, not the protein, Hershey and Chase concluded that DNA was the molecule that held the genetic information for cells to produce new viral DNA and proteins. Evidence That Viral DNA Can Program Cells Additional Evidence That DNA Is the Genetic Material ● Edwin Chargaff further proved that DNA is genetic material in in 1950 ○ The molecular structure of DNA already known, including the 4 bases: Adenine, Thymine, Guanine, and Cytosine ○ Chargaff analyzed the base composition of DNA from several different organisms and found that the base sequence varied from species to species ○ Chargaff also noticed a regularity in the ratios of nucleotide bases. In each species studied the number of adenine = number of thymines, and the number of guanine = number of cytosine ● These findings became known as Chargaff’s Rules ○ The reasoning for the base ratios is not known until the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA Chargaff’s Rules Rule 1:DNA Base composition varies between Species Rule 2: Within a species, the percentage of Adenine will be roughly equal to that of Thymine. The same is true for Guanine and Cytosine Bibliography Urry, Lisa A., et al. "Chapter 13: The Molecular Basis of Inheritance." Biology in Focus, Pearson Education, 2014, pp. 245-65.