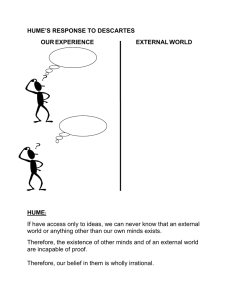

Berkeley and Hume on Self and Self-Consciousness Talia Mae Bettcher For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe any thing but the perception.1 So complained David Hume, who then went on to offer his conception of the self as an evolving bundle of perceptions, and who yet later in the Appendix, declared that his position was beset with difficulties. In this paper I argue for a fresh understanding of Hume’s famous Complaint (as well as his remarks in the Appendix). Specifically, I place the Complaint within the context of a dispute between Berkeley and Hume concerning self and self-consciousness.2 I use Locke’s innovative notion of self as the backdrop for my discussion.3 My aim is to show the value of examining this important philosophical moment other than as a response to Descartes (as our prevailing cultural account would have it).4 Instead, by looking to Berkeley we can secure a far deeper appreciation of what is at stake for Hume. Before proceeding, let me make plain that I assume Hume read Berkeley. While this has been contested in the literature, it has now been established beyond doubt.5 I assume Hume took Berkeley seriously, was influenced by him in important 1 T I.iv.6.3,164; SBN 252. Citations of A Treatise of Human Nature [T] refer to book, part, section, paragraph, and page. All references are from David Fate Norton and Mary J. Norton, eds. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). I include page references for ed. L.A. Selby-Bigge with revisions and notes by P.H. Nidditch (2nd ed.) [SBN] (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978). Citations of An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding [EHU] refer to section, paragraph, and page. All references are from Tom L. Beauchamp, ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999). 2 Citations of A Treatise concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge [PHK] refer to part and section; of Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous [3D] to dialogues number and page; of Philosophical Commentaries [PC] to entry number; of De Motu [DM] to section and page, and of Alciphron or the Minute Philosopher [ALC] to dialogue number, section, and page. All references to Berkeley are from A.A. Luce and T.E. Jessop, eds. The Works of George Berkeley, Bishop of Cloyne, 9 vols. (London/Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1948–1957). 3 Citations of An Essay concerning Human Understanding [E] refer to book, part, section, and page from Peter H. Nidditch, ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975). 4 See Kim Atkins, ed. and commentary, Self and Subjectivity (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), pp. 37–38. 5 The question was raised by Popkin (1959) in “Did Hume Ever Read Berkeley?” Journal of Philosophy 56. Subsequently, a letter (August 31, 1737) was discovered in which Hume encourages Michael Ramsay to read Berkeley’s Principles in order to better understand “the metaphysical parts of my reasoning” which was reprinted in Popkin’s (1964) “So, Hume did 193 J. Miller (ed.), Topics in Early Modern Philosophy of Mind, Studies in the History of Philosophy of Mind 9, 193–222. © Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2009 194 T.M. Bettcher ways, and was concerned to address his views. Aside from internal evidence which indicates Hume’s highest regard for Berkeley,6 commentators have shown the influence on issues including minima, the contrast between the vulgar and the philosophical, the primary/secondary distinction, and even the mind itself.7 In the view I shall defend, both Berkeley and Hume are led to a transformed conception of self-consciousness owing to a shift away from the older substancemode ontology. At its most detailed, the dispute concerns how best to conceptualize self-consciousness in light of this rejection of the older ontology. For Berkeley, consciousness of one’s own present existence is considered radically distinct from one’s awareness of ideas. They are two discrete modalities of awareness, and the latter provides no interesting information about the intrinsic features of spirits. Moreover, because ideas are not viewed as intrinsic states of spirits, the “I” that is given in consciousness needn’t be viewed as fleeting with each passing thought. Instead, spirits and ideas possess entirely different relations to time. By contrast, for Hume consciousness of oneself is nothing other than consciousness of the various perceptions which together constitute the mind. Consciousness of oneself is always consciousness of one’s past existence yielded through the associative mechanisms of memory. The very consciousness of one’s own present momentary existence which serves to ground Berkeley’s conception of spirit is left in a troubling place. I argue that Hume’s famous remarks in the Appendix, far from indicating a serious problem with Hume’s account, may constitute his own considered response to Berkeley’s conception of self-consciousness. While the details of this dispute are subtle, the stakes involved are philosophically large. Berkeley’s own account of self-consciousness yields a view of the universe and our knowledge thereof which is fundamentally bifurcated into spirits and ideas. This, for Berkeley, leads to the view that while spirits are available to consciousness, they cannot be “objects of understanding”—they cannot be subject to scientific inquiry. For Hume, of course, the goal is to show Read Berkeley,” Journal of Philosophy 61. The discussion, however, still persisted. Michael Morrisroe Jr. (1973) provides an overview of the debate in “Did Hume Read Berkeley? A Conclusive Answer,” Philological Quarterly 52 (2): 310–315. 6 The internal evidence includes the reference to Berkeley as “a great philosopher” in Hume’s Treatise discussion of abstract ideas (T I.i.7.1, 17, SBN 17), the Enquiry reference to Berkeley as a “very ingenious author” (EHU XII.v.203), and the reference to Berkeley’s Alciphron in the 1763 essay “Of National Characters” in David Hume: Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary, ed. Eugene Miller (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Classics, 1985), p. 209. 7 Raynor (1980), “‘Minima Sensibilia’ in Berkeley and Hume,” Dialogue 19: 196–199; M. R. Ayers, “Berkeley and Hume: A question of influence” in Philosophy in History, eds. R. Rorty, Schneewind, and Skinner (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), pp. 303–327; D.R. Raynor, “Hume and Berkeley’s Three Dialogues” in Studies in the Philosophy of the Scottish Enlightenment, ed. M.A. Stewart (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), pp. 231–250. Especially noteworthy, Raynor (pp. 236–237) argues that Hume’s account of mind may very well have been inspired by Berkeley’s 1734 additions to the Three Dialogues (in particular, Hylas’ proposal that the mind is a system of ideas).