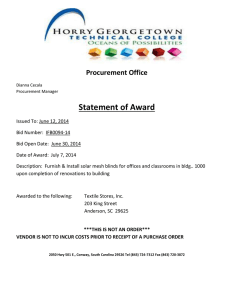

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317757170 Benchmarking approach to improve the public procurement process Article in Economic and political weekly · May 2017 CITATIONS READS 3 350 2 authors: Samir K. Srivastava Amit Agrahari Indian Institute of Management, Lucknow Indian Institute of Management, Lucknow 101 PUBLICATIONS 3,879 CITATIONS 16 PUBLICATIONS 32 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Procurement Observatory (Website : http://www.procurementobservatoryup.com/) View project Sustainable Supply Chain Coordination View project All content following this page was uploaded by Samir K. Srivastava on 02 August 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SPECIAL ARTICLE Benchmarking Approach to Improve the Public Procurement Process Samir K Srivastava, Amit Agrahari While governments in India have adopted electronic means to streamline their procurement process, the data generated by these portals have not been used to derive any meaningful information. This article presents a data-driven, multi-method approach to use benchmarking as a tool to improve the public procurement tendering process. Developing the relevant key performance indicators, it measures and compares the performance of the public procurement tendering process in Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, and West Bengal in the last five years. This work was supported by funding from the World Bank for setting up a procurement observatory in Uttar Pradesh. We thank senior officials in the UP state government and participants of the three workshops organised by the observatory. This would not have been possible without their cooperation, inputs, and insights. Finally, we thank Shanker Lal, senior procurement specialist at the World Bank and his team for their inputs and valuable suggestions at various stages of the study. Samir K Srivastava (samir@iiml.ac.in) and Amit Agrahari (amit@iiml. ac.in) teach at the Indian Institute of Management, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. 58 G overnment departments procure a large variety of goods, works, and services to carry out their operational responsibilities according to their plans and policies. Public procurement is a dynamic process involving bidders, regulators, and procurement agencies. It includes identification of needs, selection and solicitation of sources, preparation and award of contracts, and all phases of contract administration through to the end of a services contract or the useful life of an asset (Thai 2008). At the global level, public procurement spending accounts for about 15% of gross domestic product (GDP), which amounts to trillions of dollars. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries spent an average of 13% of their GDP on public procurement in 2011, while some developing countries spent up to 20% of their GDP on it (Green 2014). Developing countries are gradually recognising that an effective, open, and transparent procurement can bring significant savings in public procurement. An ability to precisely measure results in a comprehensive way may foster voluntary commitment and accountability towards the final goal of optimising public expenditure (Gardenal 2015). Given various open data initiatives, the need to benchmark and measure performance in public procurement is more urgent. Government departments worldwide procure goods, work, and services through numerous methods such as open-cry auctions, competitive bidding through request for quotation (RFQ), and agreement through negotiation. Of these, competitive bidding through RFQ, also called the two-bid tendering, is the most frequently used method for high-value procurement. In this method, the procurement agency publishes a notice inviting tender (NIT) to invite sealed technical and financial bids from participating bidders. Bidders compete by quoting the lowest possible rates. The procurement agency receives multiple quotations against RFQ from different potential bidders, and after a sequence of procedures, awards the contract. Figure 1 (p 59) shows a typical two-bid tendering process. According to the Central Public Works Department Works Manual (2003), it is the only method to award construction project contracts. Tendering is a lengthy process where it may take months to finalise the award of contract (AOC). There is a need to analyse the existing system to ascertain the causes and effects of the inordinate amount of time taken for this process. MAY 20, 2017 vol liI no 20 EPW Economic & Political Weekly SPECIAL ARTICLE Figure 1: Two-bid Tendering Process Bidders prepare techno-commercial bids and submit Publication of notice inviting tenders (NIT) Tender evaluation committee opens technical bid documents Evaluation of technical bids and selection of bidders for commercial evaluation Evaluation of commercial bids and indentification of L1 bid Award of contract Tender evaluation committee opens commercial bids Objectives of Public Procurement in India Articles 298 and 299 of the Constitution lay the foundation for public procurement. Rule 137 of the General Finance Rules (GFR) 2005 states the fundamental principles of public buying, where every authority delegated with the financial powers of procuring goods in the public interest shall have the responsibility and accountability to bring about efficiency, economy, and transparency, to treat bidders fairly and equitably, and promote competition. The central government has set out an ambitious national e-governance plan to automate various government-to-government (G2G), government-to-business (G2B), and government-tocitizen (G2C) functions to tap the efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and transparency of internet-enabled applications. In line with this, e-procurement is being adopted on a mission mode. It is mandatory in several states and central government organisations. Although e-procurement should cover the entire order– to–delivery process, it is now confined to the tendering process in India. The National Informatics Centre (NIC) launched an e-procurement portal in 2007–08, where bids are received and their status can be tracked online. Table 1 shows statewise the cumulative number of tenders published on the NIC e-procurement portal (GePNIC) till November 2015. Twenty-four states and union territories now use this portal and the estimated procurement value from 2007–08 to November 2015 is `7.43 lakh crore. More and more states and departments within states are adopting this portal. Besides, a few states such as Table 1: Cumulative Number of Tenders Published on NIC e-Procurement Portal State Number of Tenders (from 2007) State Number of Tenders (from 2007) Maharashtra 29,660 Jharkhand West Bengal 85,965 Uttarakhand Odisha 70,142 Assam Kerala 1,28,845 Puducherry 14,636 4,613 8 549 Jammu and Kashmir 35,047 Punjab 7,010 Delhi 23,681 Tripura 158 Haryana 94,547 Meghalaya 53 Uttar Pradesh 15,705 Sikkim 57 Rajasthan 32,372 Manipur 128 Tamil Nadu 54,615 Mizoram 72 Chandigarh 28,050 Arunachal 14 7,978 Nagaland 25 Himachal Pradesh Cumulative tenders (from 2007–08): 625,145. Economic & Political Weekly EPW MAY 20, 2017 vol liI no 20 Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka have their own e-procurement portals. It is estimated that only 15% to 20% of all public tenders use this or any other e-portal. While various governments in India are using e-procurement to streamline their procurement processes, data generated by these portals have not been used to derive much meaningful information. In this paper, we use data available on NIC e-procurement portals to compare and contrast the performance of e-tendering processes in the states of Uttar Pradesh (UP), Delhi, and West Bengal (WB). UP is critical to India’s growth as it is the most populous state, which gives it a dominant position in national politics. However, it lags behind in the context of public procurement practices and outcomes. Unlike states such as Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Rajasthan, UP has, so far, not enacted any legislation to govern public procurement. In 2008, e-procurement was introduced in the state. But unlike in WB and Maharashtra, there is no government order (GO) notification making eprocurement mandatory. Therefore, as of now, data sharing is voluntary. However, e-procurement adoption has been gradually picking up in the state since 2011, and it seems to be in place in at least a few departments. From 2008 to November 2015, the e-procurement portal has supported 15,705 tenders managing the process for `11,475 crore, which represents about 15% to 20% of the total public procurement spent in UP for the period. While this paper presents a generic benchmarking approach to improve public procurement processes, we have applied it to the context of UP in particular. UP is benchmarked with Delhi and WB. Delhi is a neighbouring state with a per capita net state domestic product (NSDP, at current prices for 2014–15) at `2,40,849. While it is predominantly urban, WB bears a geopolitical similarity with UP. UP is among the poorest states with a per capita NSDP of `40,373, and WB is around the national average at `78,903 (Statistics Times 2015). Quantitative results obtained after comparing the three states were shared with the relevant stakeholders in three workshops to identify improvement opportunities for UP. Literature Review Public procurement is more regulated than private procurement, and there are more rules to comply with, more policy considerations to take into account. At the national, supranational, and international levels, public procurement sits within legislative, administrative, and judicial frameworks (Murray 2009). Even those public bodies that genuinely wish to change are restricted by standing orders, public accountability, and probity constraints. Elected members “steer” in determining outcomes to be achieved, what public money is to be raised, and on what public services it is to be spent, unshackled by defining service outcomes through the constraints of their own workforce, while “officers row” in recommending the best fit delivery means (Lyne 1996: 1–6). Westring and Jadoun (1996) recommend that procurement procedures should be characterised by clear rules and by means to verify that those rules were followed. Carayannis 59 SPECIAL ARTICLE and Popescu (2003) enumerate a number of weaknesses in the public procurement process such as lack of information quality, absence of a clear information technology (IT) policy, a complicated procedure and extended relationships, and excessive state intervention, including favouritism in awarding public contracts and resistance to change. Many jurisdictions worldwide have listed, implicitly or explicitly, various management objectives for public procurement (Jones 2002; Qiao and Cummings 2003; Thai 2008). Procurement has to be evaluated in its complexity, which encompasses numerous goals—to rationalise expenditure, to reduce “administrative confusion” and costs, to foster operational efficiency (Croom 2000), and to explore ways to automate certain procurement activities (Aisbett et al 2005). Competitive sourcing in public procurement is expected to encourage innovation as well as improve efficiency and performance (US Government Accountability Office 2005). In recent years, countries, such as Albania, Brazil, Ghana, and India, have embarked on substantive public procurement reforms, mainly focusing on publishing more information and increasing transparency in the bidder selection processes (Estache and Iimi 2011). Transparency is a core governance value. It provides an assurance to investors that contracts will be awarded in a fair and equitable manner (Smith-Deighton 2004). The literature reveals that three factors are essential for a public procurement regime to be classified as transparent. First, there have to be clear public procurement rules. All participants should be informed about the procurement rules that will be applied by the contracting authority (for instance, what are the criteria for selecting suppliers, awarding a contract, and so on). Second, procurement opportunities should be public to enable all possible interested bidders to participate. This is achieved by publishing procurement opportunities in national and regional bulletins/newspapers. Third, the opportunity should be given to scrutinise decisions and to enforce the rules to ensure that the procurement agency has adhered to them and that the decision was motivated by commercial consideration, not self-interest. To actually measure these, certain key performance indicators (KPIs) need to be in place. Impact of e-Procurement E-procurement may generate positive impacts, especially in the efficiency, effectiveness, dematerialisation, competitiveness, and transparency impact dimensions (Gardenal 2015). Providing a better quality of information will result in a satisfactory purchase (Erridge et al 1999). In the Indian context, Panda and Sahu (2011) carried out a qualitative case study and found that differences in the enabling environment (like IT infrastructure, internet penetration and IT literacy) were major hurdles to implementation of these practices. Schapper et al (2006) argue that the public procurement environment is characterised by tension due to conflicting stakeholder interests at the political, business, community, and management levels. This is exacerbated by competing claims between executives, lawyers, technologists, and politicians for lead roles in this arena. They suggest that the application of 60 new technology in this discipline offers a qualified potential to substantially resolve these tensions. Relevance of Benchmarking in Public Procurement Benchmarking and performance measurement are the main techniques that have been used by leading researchers and practitioners to improve business processes. It is a practice that implies a systematic measurement and comparison of the activities of individuals and organisations with a view to improving their efficiency and quality. Benchmarking may be distinguished from other traditional forms of evaluation by its attempt to visualise best practice through normalising comparison and by urging public entities to ask themselves what they can do to promote “best practices” (Triantafillou 2007). It enables and motivates one to determine how well one’s current practices compare to other practices, experience best practices in action, locate performance gaps, prioritise opportunities and areas for improvement, and improve current levels to world-class standards (Palaneeswaran and Kumaraswamy 2000). Benchmarking has been extensively used to understand various socio-economic phenomena. Kothari and Joshi (2002) describe a simple, quick, and easy-to-administer tool for measuring literacy skills. Thomas (2007) suggests that the Indian aviation industry may implement a mass transit strategy by benchmarking with China. Different types of benchmarking have been used in purchasing departments of business enterprises in both developed and developing countries (SanchezRodriguez et al 2003). Procurement benchmarking may be used to measure the performance of a supplier of goods or services on the basis of quality price and timely delivery (Tudor 2005). Raymond (2008) investigates the technique of benchmarking to improve the quality of the public procurement process and discusses the importance of benchmarking to overcome perceived weaknesses with these processes in a case study of Sri Lanka. She suggests that reform solutions within government procurement systems must include measures that address issues of accountability, transparency, value for money, a professional work force, and ethics. To be effective, a public procurement performance management system must focus on “measuring the correct things” (Murray 2009). The literature review identifies a few gaps. Murray (2009) finds that there is an inbuilt bias in public procurement research through over-reliance on procurement managers as the key respondents. There has been little published literature on actual observations and practice. Further, limited empirical research has been conducted on e-procurement implementation, benefits, and value in the public sector (Gardenal 2015; Vaidya et al 2004). Data generated by various e-procurement portals is publicly available but there have been no efforts to derive meaningful information by carrying out comparisons between various departments and governments. This paper attempts to bridge some of these gaps by defining the key performance indicators for the public procurement tendering process, and by comparing them across UP, Delhi, and WB. MAY 20, 2017 vol liI no 20 EPW Economic & Political Weekly SPECIAL ARTICLE Data Used and Approach Adopted The NIC has implemented e-procurement portals for UP, WB, and Delhi, among others. These portals provide tender-wise e-tendering process information. We use these data to develop base line statistics and use them to measure and compare procurement performance across the three states for the last five years. As the data available at the NIC portal are not easily amenable to analysis and comparison, we designed a web crawler that collects tender-wise data in a tabular format that allows easy analysis and comparison within and across states. In this paper, we analyse the data from three states, although the web crawler collected data from eight states and the e-procurement portals of some public sector undertakings (PSUs). We also designed a data visualisation tool that allows easy comparisons among various states on different KPIs using simple drop-down menus. This tool is available at www.procurementobservatoryup.com. So, the approach used in this paper is generic and can be used in other contexts as well. Following a multi-method approach to give meaning to the numbers generated by quantitative analysis, we conducted three workshops with stakeholders drawn from government departments of UP, multilateral development agencies, and academics from India and the US. The workshops were carried out under the umbrella of the public procurement observatory for UP that we established at the Indian Institute of Management, Lucknow, in July 2013. By observing procurement processes and advocating better practices, this observatory aims at enhancing public procurement performance in the state. It shares the best global practices (from other states in India and countries abroad) in procurement management with decisionmaking/policymaking state government officials through workshops, newsletters, and other means. Developing KPIs for a Tendering Process In line with the GFR 2005, we develop KPIs to measure efficiency, fair and equitable treatment of bidders, and promotion of competition. Efficiency is defined in terms of the time taken to execute various activities in the procurement process. It captures various delays and changes to show if the process is running efficiently. Fair and equitable treatment is defined as creating a process that provides equal opportunities and a level playing field to all bidders. Promotion of competition among bidders needs a larger number of bidders participating in the process, and process design should enable and encourage this. The number of KPIs should neither be too large nor too small. Further, they should be simple enough to measure and understand so that they can be applied to research data sets. Based on this, we developed an initial set of KPIs and, after due deliberations with academia and multilateral development agencies, was further narrowed down so that it could be applied across any set of tenders. The logic for their importance and selection is described here, and a detailed KPI list, along with their measures, is summarised in Table 2 (p 62). (i) Average delay in technical bids opening: If bids are not opened on the scheduled date (and at the scheduled time), it Economic & Political Weekly EPW MAY 20, 2017 vol liI no 20 causes inconvenience to bidders and has an impact on their trust in the entire process. (ii) Average time taken to evaluate technical bids: Technical bid evaluation can be made simple using pre-defined technical qualification criteria. An efficient process should not take unduly long. Too much time taken indicates poorly designed technical specifications, lack of well-defined evaluation criteria, and a lack of capable human resources evaluating the technical bids. (iii) Average time from technical evaluation to financial bid opening: After technical evaluation, financial bids should be opened at the earliest. Any delay indicates a lack of planning and resource unavailability. (iv) Average time taken to evaluate financial bids: Faster commercial bid evaluation and award of contracts indicates that there is no post-tender negotiation with the L1 bidder. It also indicates that the administrative and financial approval processes are not taking too long to complete. (v) Average time taken from NIT publication to financial evaluation: It is a measure of the procurement order cycle. The government agency should take a reasonable time for it. A too high or too low value in this KPI is undesirable. (vi) Average bid validity days: The Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) in a circular (No 31/11/08) observed that while a short validity period calls for prompt finalisation by observing a specific timeline for processing, a longer validity period has the disadvantage of bidders loading their offers in anticipation of likely increase in costs during the period. Hence, it is important to fix the period of validity with utmost care. (vii) Percentage of tenders where cycle time is higher than the bid validity period: At the time of submitting the bids, buyers mandate their validity in days. The tendering process cycle time from bid submission to financial bid evaluation is expected to take less time than the bid validity. A higher score in this indicates a less-efficient tendering process. (viii) Average payment options for bidders: Bidders are expected to deposit 2%–5% of the estimated tender value as earnest money to participate in the process. Earnest money can be deposited in the form of a fixed deposit receipt, banker’s cheque, banker’s guarantee, demand draft, and small saving certificates. Providing more options to the bidders ensures larger participation. (ix) Bidder adequacy ratio for technical bids: This is the average ratio of initial number of bidders over the number of bidders awarded the contract. Although the GFR states a minimum number of initial bidders to initiate any tendering process, the desired number should be much higher than the minimum number. To ensure competition among bidders, this ratio should be greater than 3. A higher score in this KPI indicates more competition among bidders. (x) Bidder adequacy ratio for financial bids: In some cases, almost all technically qualified bidders are awarded the contract since no single bidder may have the capacity or capability to fulfil the contract. In other cases, the work is divided into small pieces and all bidders are given a piece of the contract even if capacity is not a constraint. This defeats the very purpose of conducting the tendering process. 61 SPECIAL ARTICLE Table 2: Key Performance Indicators and Their Measures No Key Performance Indicator Name Measure i ii iii iv v Average delay in technical bids opening (in days) Average time taken to evaluate technical bids (in days) Average time from technical evaluation to financial Average time taken to evaluate financial bids (in days) Average time taken from NIT publication to financial evaluation (in days) vi Average bid validity days vii Percentage of tenders where cycle time is higher than the bid validity period viii Average payment options for bidders (in number) ix Bidder adequacy ratio for technical bids x Bidder adequacy ratio for financial bids xi Tender award with only one bidder available for financial evaluation (in percentage) xii Average time allowed to bidders for bid preparation and submission (in days) Actual technical bid opening date–scheduled bid opening date Date of uploading technical evaluation–actual technical bid opening date Actual financial bid opening date–date of uploading technical evaluation bid opening (in days) Date of AOC–actual financial bid opening date Date of AOC–NIT publication date Available in NIT document Percentage of process instances where cycle time is higher than bid validity days Number of payment options are available in NIT document Ratio of initial bidders to the number of bidders awarded the contract Ratio of technically qualified bidders to the bidders awarded the contract Percentage of instances where tenders are awarded to a single commercial bidder Bid submission end date–NIT publication date (xi) Tender award with only one bidder available for financial evaluation: After technical evaluation, if only one bidder is selected for commercial evaluation, it almost converges to the case of single bid tendering. This should be discouraged as it may block competition. (xii) Average time allowed to bidders for bid preparation and submission: After publishing a notice inviting tenders, the government agency should give potential bidders sufficient time for bid document preparation and submission. This will ensure that all interested bidders participate in the process. We carried out a detailed analysis of procurement process on the developed KPIs. The analysis is based on the tendering processes in UP and Delhi in the last five years, and WB in the last four years (it adopted eTable 3: Number of Tenders, 2011 to 2015 procurement in only State Number of Tenders Observed 2012). Table 3 shows the 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Uttar Pradesh 121 11 164 375 639 number of tenders in Delhi 629 1,077 1,344 1,417 551 each of these states in West Bengal NA 1,491 3,371 6,774 6,293 the last five years. To Table 4: Number of Participants in the Three Workshops Departments I Workshop 62 16 14.75 UP 14 12 10.6 Delhi 10 WB 8 7.31 7.23 6 3.59 4 4.42 2.88 2.71 3.45 4.1 2.84 3 2 2 1 0 2 0 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 No of Participants II Workshop III Workshop 1 5 2 1 2 0 1 2 2 0 2 0 1 2 0 5 0 0 1 2 6 2 0 9 0 2 0 2 0 0 1 8 2.8 3 1.28 2 Analysis and Interpretations UPSRTC UP health system strengthening project Multilateral development agencies Public works department Planning department Industries department UP Bhoomi Sudhar Nigam Academics and training institutes Tourism department PICUP Stamp and registration department UP Finance Corporation Agriculture (dairy + fisheries) Food and civil supplies department National Informatics Centre Others Figure 2: Average Delay in Technical Bids Opening, 2011 to 2015 0 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 bring logical consistency to our analysis, we limited it to only tenders that reached the AOC stage. To interpret meaning and derive insights, our analysis was shared with UP’s drawing and disbursing officers (DDOs), comprising principal secretaries, secretaries, and other senior officers, multilateral development agency executives, and personnel from Indian and US academic and training institutes in three workshops. Details on participation are in Table 4. The following sections are based on workshop deliberations, key findings, and observations on the KPIs across the three states. Average delay in technical bids opening: Figure 2 shows the average delay in technical bids opening in the three states in days. We observe that UP has improved a good deal over the years—now the average delay is around one day, from around 15 days four years ago. Delhi has also improved consistently, while in WB, it is around three days. Average time taken to evaluate technical bids: Technical bid evaluation can be made simple using predefined technical qualification criteria. So, an efficient process should not take an unduly long time. Figure 3 (p 63) shows that, while Delhi has improved its performance to reach an average of one day, MAY 20, 2017 vol liI no 20 EPW Economic & Political Weekly SPECIAL ARTICLE Figure 3: Average Time Taken to Evaluate Technical Bids, 2011 to 2015 Figure 5: Average Time Taken to Evaluate Financial Bids, 2011 to 2015 35 120 32.84 30 100 25 24.49 UP 88 Delhi 80 19.55 20 108 WB 59 60 UP 15 Delhi 10 5 4.79 3.36 3.18 3.56 2.47 2.33 2012 2013 0.1 5.79 3.96 0.95 0.95 2014 2015 0 32 31 22 22 19 21 20 22 12 11 11 0 2011 Figure 4: Average Time from Technical Evaluation to Financial Bid Opening, 2011 to 2015 35 30 39 40 WB 28.69 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Figure 6: Average Time Taken from NIT Publication to Financial Evaluation, 2011 to 2015 180 160 159 UP 142 140 25 120 20 UP Delhi WB 57 49 3.1 0.62 0.9 2.39 1.06 2.23 1.9 0.7 2.41 1.08 0.25 2.14 0 2012 2013 2014 Average time from technical evaluation to financial bid opening: Figure 4 shows that all the three states are doing satisfactorily on this KPI, though there were high values for UP and Delhi in 2011. WB may possibly take action to improve on this. Average time taken to evaluate financial bids: A faster financial bid evaluation and award of contract indicates that there is no post-tender negotiation with the L1 bidder. It also indicates that the administrative approval processes are not taking unduly long. While Delhi and WB show a generally decreasing trend (Figure 5), UP shows a higher average time. In 2013, UP took on an average of 108 days to complete this activity per tender, while Delhi took almost 12 days. Stakeholders opine that multiple layers of approval in UP may be the reason for such poor performance. So, there is an urgent need to cut down layers of approval and make the process more efficient. 31 35 2013 2014 35 25 20 0 2011 2015 UP alarmingly took almost 25 days on an average to evaluate technical bids in 2015. So, although tenders are opened around the due date, technical evaluation takes an unduly long time. Stakeholders opine that this may be due to an increase in scrutiny of the tendering process by governments and private agencies. While other states are also subject to such scrutiny, they have modified their procurement process to make it fairer, more equitable, and more transparent. UP has not made any major changes to its procurement process so far. 50 45 40 5 2011 70 67 60 6.42 88 Delhi 80 15 10 WB 94 100 2012 2015 the three states. However, it is still much higher in UP and needs attention. The process time components need to be worked on and the bid validity days perhaps need to be increased in certain categories (Figure 6). Average bid validity days: This refers to the precise period of time the bidders certify for which their bids can be considered valid. After this, the bidders are at liberty to change their bid price if the contract is not signed by the last date of the bid validity period. The CVC (Circular No 31/11/08) observed that while a short validity period calls for prompt finalisation by observing a specific timeline for processing. A longer validity period has the disadvantage of bidders loading their offers in anticipation of a likely increase in costs during the period. Hence, the average bid validity period is a measure of process Figure 7: Average Bid Validity Days, 2011 to 2015 160 Delhi 140 104.1 100 91.5 134 99 89.4 84.6 130.2 122.8 121.5 UP 120 WB 94.7 102 97.7 87.2 73.4 80 60 40 20 Average time taken from NIT publication to financial evaluation: The procurement order cycle time is decreasing for all Economic & Political Weekly EPW MAY 20, 2017 vol liI no 20 0 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 63 SPECIAL ARTICLE Figure 10: Bidder Adequacy Ratio for Technical Bids, 2011 to 2015 9 7.83 8 6.74 7 Figure 8: Percentage Tenders Where Cycle Time is Higher than the Bid Validity Period, 2011 to 2015 70 60 59.5 51.8 50 WB 36.4 40 34.7 3 8.2 9.1 4.8 5.3 2012 2013 1.7 2014 2.69 2 1.72 Delhi 1.5 2.48 2.46 2.41 2.5 1.68 1.82 1.76 1.74 UP 1.04 1 1 0.5 0 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 economy and it is important to fix the period of validity with utmost care. Figure 7 (p 63) shows the average bid validity days for the three states for the five years under study. Percentage tenders where cycle time is higher than the bid validity period: Process cycle time as measured by time between bid submission end date and date of award of contract has generally been unduly long and often exceeded the bid validity period. Figure 8 shows the percentage of awarded tenders where the process cycle time is higher than bid validity days. Discussions and interactions suggest that such delays could be mainly because of multiple layers (between tender evaluation committee and accepting authority) of scrutiny, particularly in high value procurements. Further, procurements are based on budgetary provisions and procurement planning and monitoring do not cover timelines. This needs attention in UP and possibly process redesign. WB shows better performance on this indicator. Average payment options for bidders: Bidders are expected to deposit 2%–5% of estimated tender value as earnest money deposit (EMD) to participate in the tendering process. Rule 157 of the GFR states that this money can be deposited in the form of a fixed deposit receipt, banker’s cheque, banker’s guarantee, demand draft, and small saving certificates. Providing more options to the bidders promotes competition. Figure 9 shows average payment instruments per tender across the three states. Delhi tops the charts with consistent 64 2.62 2.36 1 2011 3.15 2.96 WB 3.81 3.35 2012 2013 2014 2015 Figure 11: Bidder Adequacy Ratio for Financial Bids, 2011 to 2015 3.5 2.81 4.83 3.81 0 2015 Figure 9: Average Payment Options for Bidders, 2011 to 2015 3 3.99 3.83 3.98 3.63 UP 5.18 2 10.2 10.3 10 7.7 0 2011 Delhi 4 20 8 WB 5 Delhi 30 10 5.86 6 UP 5 4.5 4 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 WB 3.71 3.72 3.51 3.18 Delhi 4.42 4.17 3.47 3.3 3.29 2.65 2.25 2.08 1.79 UP 2011 2012 2013 1.6 2014 2015 improvement, while UP has also picked up considerably. WB is stagnant and needs to take action. Bidder adequacy ratio for technical bids: This is defined as the number of initial bidders to the number of bidders awarded the contract, and is a measure of adequate competition at the early stage of the process. The GFR states some minimum number of initial bidders to initiate any tendering process; however, the desired number of bidders should be much higher than this minimum number. As illustrated in Figure 10, while Delhi shows very high bidder participation, WB and UP are not performing as well. In UP, there has been improvement over the years. Our workshop participants opined that ease of doing business may be a reason for higher bidder participation in Delhi. In UP, bidders need to get registered in multiple departments as there is no single procurement coordination agency. A single point registration of bidders may be introduced, which may apply to all purchasers in the state and allow interested bidders to apply for registration any time. Bidder adequacy ratio for financial bids: This is defined as the number of technically qualified bidders and is a measure of adequate competition at a later stage of the process. As illustrated in Figure 11, while Delhi shows good and improving performance, WB and UP do not. UP has declined over the years, which is very alarming from the fairness and competition point of view. A closer examination reveals that in some cases almost all technically qualified bidders were awarded the MAY 20, 2017 vol liI no 20 EPW Economic & Political Weekly SPECIAL ARTICLE Figure 12: Tender Award with Only One Bidder Available for Financial Evaluation, 2011 to 2015 16 13.68 14 13.15 12.73 12 10 10.89 9.61 WB 10.21 Delhi 7.62 8 6.61 6.52 6 6.7 6.13 4.85 UP 4 2 0.61 0 0 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Figure 13: Average Time Allowed to Bidders for Bid Preparation and Submission, 2011 to 2015 25 23.5 23.17 Delhi 15.02 15 10 19.43 WB UP 20 12.17 11.92 15.31 14.05 11.15 14.21 12.47 9.67 9.6 2014 2015 7.44 5 0 2011 2012 2013 contract despite no capacity constraint, while in others, the bid was awarded to a single technically qualified bidder. Tender award with only one bidder available for financial evaluation: Figure 12 shows the percentage of instances in the overall tendering process where the bid is awarded to a single financial bidder left after technical evaluation. This is similar to the case of single bid tendering and should be discouraged. Delhi and WB in particular need to take action on this. Average time allowed to bidders for bid preparation and submission: It is assumed that giving sufficient time for bid document preparation and submission ensures that the NIT reaches everyone and interested bidders can participate in the process. Though Delhi scores the lowest among the three states, it has very good vendor participation. Therefore, we can conclude that UP and WB should set the time allowed for bid preparation and submission more judiciously as it may increase the total procurement cycle time without much impact on vendor participation (Figure 13). Pathways for Improvements Based on the deliberation in the three workshops, we highlight the potential for improvements in the procurement processes in the state of UP. These may have significant impact on effective services delivery to the citizens. Economic & Political Weekly EPW MAY 20, 2017 vol liI no 20 Need for training and capacity building: Training and capacity building on public procurement could lead to an easier, efficient, economic and more transparent procurement process. Potential bidders also need to be trained extensively for e-tendering. Post the first workshop, the UP State Planning Institute identified resource persons/master trainers and carried out two programmes on public procurement. The World Bank and IIM Lucknow extended support through their experts on Indian systems of procurement in these two programmes. Besides classroom training, it is suggested that capacity building and training can be imparted through massive open online courses (MOOCs) on public procurement. The World Bank and its partners have created an India-specific free online Certificate Program in Public Procurement (CPPP). Need for procurement process redesign: Analysis of the data on UP reveals the e-tendering process is marred by delays, which entail waiting. The average financial evaluation takes around 22 days and the average time from NIT publication to financial evaluation is around 70 days. Similarly, observations of more than 1,000 tenders in 2012 reveals that cancelled tenders spiked to 50%, while they were in single digits in the remaining four years. A possible but empirically unproven association could be a change in the political dispensation in 2012 and associated changes in the administrative structure. Several interesting process redesign ideas emerged in the workshops. It was observed that the state and central public procurement rules are not harmonised, resulting in ambiguity and confusion. Policies for specialised services (for example, consultancy) and specialised projects (for example, PPP) need to be framed properly for UP. Archaic rules such as mandatory newspaper advertising for any procurement above `50,000 also need to be done away with in these changed times. Simple ideas like buy-back for e-waste may be considered in the state’s IT procurement policy. Additionally, using the NIC’s post tendering module may lead to better and auditable procurement planning and control. The state may think about establishing a nodal agency for government purchasing along with a procurement ombudsman. A thorough review, updating, and standardisation of the procurement policy is the need of the hour. It is felt that standardised manuals (similar to handbooks on election law in Licensing by EPWI EPW has licensed its material for non-exclusive use to only the following content aggregators—Contify, Factiva and Jstor. Contify currently disseminates EPW content to LexisNexis, Thomson Reuters, Securities.com, Gale Cengage, Acquiremedia and News Bank. Factiva and Jstor have EPW content on their databases for their registered users. EPW does not have licensing arrangements with any other aggregators. EPW requests readers to let it know if they see material on any unlicensed aggregator. EPW needs the support of its readers to remain financially viable. 65 SPECIAL ARTICLE terms of comprehensiveness) would make the procurement process quicker, easier, unambiguous, economic, and more transparent. Further, periodic review of these rules and guidelines should be done in future through Periodic Policy Review Commissions. Better bidder management for higher participation: Almost 20%–30% of tenders in the last five years received no bids. In these cases, the cost of procurement (such as the NIT publication cost and resource cost) goes waste, and services to citizens get delayed, causing losses. These clearly reflect bidder apathy and market making failure. While Delhi shows high supplier participation, WB and UP do not. Our workshop participants opined that ease of doing business may be a reason for higher bidder participation in Delhi. In UP, bidders need to get registered in multiple departments and there is no single procurement coordination agency. A single point registration of bidders may be introduced which may apply to all procurement processes in the state. It should also allow interested bidders to apply for registration any time. Besides, there are a few issues related to bidder registration and blacklisting as well as payment that need to be resolved. Bidder registration and blacklisting processes need to be simplified. An electronic platform could be a good solution. Now, the payment has to be approved by the treasury; this process too needs to be streamlined and simplified. For example, governments may create a “pooling bank account” for government departments and another one for PSUs. A similar practice is being followed in Kerala. Transparent public procurement process using e-tendering: E-tendering not only brings efficiency in public procurement, but also makes the process more transparent, leaving an auditable trail. Such a trail will make statewide procurement management information available for analysis or policy formulation. Since the NIC’s e-tendering system does not mandate information sharing, an improvement in the e-tendering system can ensure that AOC information of all financially evaluated tenders is shared before creating a new tender. In WB, e-procurement has been made mandatory, and the number of tenders on the e-tendering portal has gone up rapidly. However, in UP, where e-tendering is not mandatory, the number on the e-tendering portal is still limited. Departments such as the PWD carry out e-tendering only for procurement worth more than `1 crore. It could be beneficial to make e-tendering mandatory in UP. Overall, while technology can bring efficiency and transparency in the public procurement process, there is a need for education and capacity building on public procurement in UP. Along with process redesign and policy review, UP needs to Subscribe to the Print edition + Digital Archives When you subscribe to the Print + Digital Archives, you get... • 50 issues of the print edition every year delivered to your door • All special and review issues • Archival access on the website for all content published since 1949 to date (including the Economic Weekly) • Web Exclusives • Featured themes – articles on contemporary issues from our archives • And a host of other features on www.epw.in To subscribe, visit: www.epw.in/subscribe.html Attractive subscription rates are available for students, individuals and institutions. Postal address: Economic and Political Weekly, 320-322, A to Z Industrial Estate, GK Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai 400 013, India. Tel: +91-22-40638282 | Email: circulation@epw.in 66 MAY 20, 2017 vol liI no 20 EPW Economic & Political Weekly SPECIAL ARTICLE focus on better vendor management practices. To bring greater transparency in public procurement, contract implementation data may be shared in the public domain, so that the state’s contract implementation process performance can be measured as well. Conclusions The preconditions for achieving a sound public procurement system are integrity and commitment to good governance practices through the provision of well-designed legislation and supporting regulations and review processes. Proper performance measures and their benchmarking also help in identifying improvement methods and pathways. This article is an early attempt at this with particular focus on UP. It helps to measure, compare, and contrast public procurement tendering process performance on well-defined KPIs across three Indian states for five years to derive managerially relevant insights, and also suggests a few paths for improvements. The same could be extended across other states and also PSUs. The ministries of finance and planning must review the current legislations and identity areas for improvement. Training needs to be provided to all managers and staff involved in public procurement to enhance capacity, thereby improving performance in terms of efficiency. The state government also needs to consider forming an independent regulatory body which will be responsible for transparency and accountability in public procurement. The government should also develop References Aisbett, J, R Lasch and G Pires (2005): “A DecisionMaking Framework for Adoption of e-Procurement,” International Journal of Integrated Supply Management, 1(3), pp 278–93. Carayannis, E G and D Popescu (2003): “Profiling a Methodology for Economic Growth and Convergence: Learning From the EU e-Procurement Experience for Central and Eastern European Countries,” Technovation, 25(1), pp 1–15. Central Public Works Department (2003): Works Manual, Director General (works), New Delhi: J M Jaina and Brothers. Croom, S R (2000): “The Impact of Web-based Procurement on the Management of Operating Resources Supply,” The Journal of Supply Chain Management, 36 (1), pp 4–13. Erridge, A, R Fee and J Mcllroy (1999): “An Assessment of Competitive Tendering Using Transaction Cost Analysis,” Public Money and Management, 19 (3), pp 37–42. Estache, A and A Iimi (2011): “Bidders’ Entry and Auctioneer’s Rejection: Applying a Double Selection Model to Road Procurement Auctions,” Journal of Applied Economics,16(2), pp 199–23. Gardenal, F (2015): “A Model to Measure e-Procurement Impacts on Organizational Performance,” Journal of Public Procurement, 13(2), pp 215–42. Green, W (2014): “UN Launches Scheme to Use Global Public Procurement to Boost Sustainability, viewed on 29 July 2015, http:// www.supplymanagement.com/news/2014/ un-launches-scheme-to-use-global-publicprocurement-to-boost-sustainability. Jones, D S (2002): “Procurement Practices in the Singapore Civil Service: Balancing Control and Economic & Political Weekly View publication stats EPW MAY 20, 2017 some product-related environmental policy instruments such as eco-labelling and extended producer responsibility. This paper concentrates on performance under the existing policies and set-up. A very rich area of research is to carry out a review of existing procurement practices and related documents in a few selected Indian states. This will enable scholars to document the existing practices and also unpack each state’s performance on various KPIs. Further, many international organisations’ voluntary rules on government procurement could be a useful mechanism for ensuring that public procurement procedures are efficient. They also provide an opportunity to reduce the uncertainty of bidder participation by increasing transparency and accountability. Lack of competition in public procurement may lead to squandering of public money and the KPIs on competition clearly show either lack of competition or less competition (particularly at the financial bid evaluation stage). There are many policy options that may increase competition in the domestic market—deregulation, trade liberalisation, and other market opening policies— and these could be studied. At a practical level, one could envisage procurement being opened up at different speeds in different sectors—the most sensitive being retained for domestic firms and others being retained for regional firms—while introducing broad-based transparency measures. Finally, an analysis of the state of competition in the public procurement systems of Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu, two states that have a public procurement law, could lead to useful insights. Delegation,” Journal of Public Procurement, 2 (1), pp 29–53. Kothari, B and A Joshi (2002): “Benchmarking Early Literacy Skills: Developing a Tool,” Economic & Political Weekly, 37 (34), pp 3497–99. Lyne, C (1996): “Strategic Procurement in the New Local Government,” European Journal ofPurchasing and Supply Management, 2(1), pp 1–6. Murray, J G (2009): “Improving the Validity of Public Procurement Research,” International Journal of Public Sector Management, 22 (2), pp 91–103. Palaneeswaran, E and M M Kumaraswamy (2000): “Benchmarking Contractor Selection Practices in Public-Sector Construction: A Proposed Model,” Engineering Construction & Architectural Management, 7(3), pp 285–99. Panda, P and G P Sahu (2011): “e-Procurement Implementation: Comparative Study of Governments of Andhra Pradesh and Chhattisgarh,” IUP Journal of Supply Chain Management, 8(2), pp 34–67. Qiao, Y and G Cummings (2003): “The Use of Qualifications-Based Selection in Public Procurement: A Survey Research,” Journal of Public Procurement, 3 (2), pp 215–49. Raymond, J (2008): “Benchmarking in Public Procurement,” Benchmarking: An International Journal, 15(6), pp 782–93. Sanchez-Rodriguez, C, R A Martinez-Lorente and G J Clavel (2003): “Benchmarking in the Purchasing Function and Its Impact on Purchasing and Business Performance,” Benchmarking: An International Journal, 10(6), pp 457–71. Schapper, P R, J N Veiga Malta and D L Gilbert (2006): “An Analytical Framework for the Management and Reform of Public Procurement,” Journal of Public Procurement, 6(1/2), pp 1–26. vol liI no 20 Smith-Deighton, R (2004): “Regulatory Transparency in OECD Countries: Overview, Trends and Challenges,” Australian Journal of Public Administration, 63(1), pp 66–73. Statistics Times (2015): “GDP per Capita of Indian States,” http://statisticstimes.com/economy/ gdp-capita-of-indian-states.php, accessed on 26 February 2016. Thai, K V (2008): International Handbook of Public Procurement, New York: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. Thomas, P S (2007): “Aviation Strategy: Filling a Crucial Void,” Economic & Political Weekly, 42(31), pp 3205–06. Triantafillou, P (2007): “Benchmarking in the Public Sector: A Critical Conceptual Framework,” Public Administration Journal, 85(3), pp 829–46. Tudor, S (2005): “Benchmarking procurement,” Summit, 8(2), pp 17–19. Vaidya K, G Callender, A S M Sajeev and J B Gao (2004): “Towards a Model for Measuring the Performance of e-Procurement Initiatives in the Australian Public Sector: A Balanced Scorecard Approach,” Paper presented at the Australian e-Governance Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 14–15 April. US Government Accountability Office (2005): “Competitive Sourcing: Greater Emphasis Needed on Increasing Efficiency and Improving Performance,” Journal of Public Procurement, 5 (3), pp 401–41. Westring, G and G Jadoun (1996): Public Procurement Manual for Central and Eastern Europe, Turin: International Training Centre of the ILO. 67