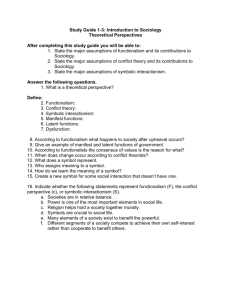

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333858560 Evaluating sense of community in the residential environment from the perspectives of symbolic interactionism and architectural design Article in Journal of Community Psychology · June 2019 DOI: 10.1002/jcop.22214 CITATION READS 1 194 2 authors: Hanieh Haji Molana Richard E Adams California State University, Sacramento Kent State University 9 PUBLICATIONS 2 CITATIONS 100 PUBLICATIONS 3,632 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: A Model of Compassion Fatigue Prevention and Resilience View project World Trade Center Terrorist Attacks View project All content following this page was uploaded by Hanieh Haji Molana on 21 June 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SEE PROFILE Received: 16 January 2019 | Revised: 10 May 2019 | Accepted: 14 May 2019 DOI: 10.1002/jcop.22214 RESEARCH ARTICLE Evaluating sense of community in the residential environment from the perspectives of symbolic interactionism and architectural design Hanieh H. Molana | Richard E. Adams Department of Geography, College of Art and Sciences, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio Correspondence Hanieh H. Molana, College of Art and Sciences, Department of Geography, Kent State University, 325 S Lincoln St, Kent, OH 44240. Email: hhajimol@kent.edu Abstract The paper fills the gap between the design and the actuality of how buildings, and its surroundings, urban design, and the built environment influence its occupants’ behavior and interactions. We assess how the built environments can be influenced by humans and their control, both physical and symbolically, of the urban landscapes. In this regard, our paper merges symbolic interactionism, sense of community, and architectural design to aid our understanding of the man–environment relationship. Specifically, we assess qualitative data on Ekbatan Residential Complex in Tehran. We use Ekbatan as a case study to see how a sense of community among residents reflects both physical features of the complex and the symbolic meaning attached to these features by residents and those living outside the community. We conclude by suggesting that combining the interests of urban sociologist, community psychology, and architects via symbolic interactionist concepts may be a fruitful avenue for studying factors affecting sense of community and larger urban processes. KEYWORDS community studies, environmental psychology, human interaction, residential environment, sense of community, symbolic interactionism 1 | INTRODUCTION Social scientists have long been interested in the relationship between the built environment and sense of community (R. E. Adams, 1992; R. E. Adams & Serpe, 2000; Durkheim [1897] 1966; Tonnies, 1957; Wise, 2014). J. Community Psychol. 2019;1–12. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/jcop © 2019 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. | 1 2 | MOLANA AND ADAMS Many early, and some contemporary, theorists lamented the loss of connections with others as the size and density of urban areas increased (e.g., Nisbet, 1953; Simmel [1917] 1950; Tonnies, 1957), and urban residents suffered psychologically from an overstimulating environment (Cohen, 1985; Milgram, 1970; Simmel [1917] 1950). The claim was that residents of small towns and rural communities have an easier time making strong social ties to others, whereas people living in urban areas suffer from a lack of community, resulting in poor psychological health and high rates of nonconforming behavior (Cohen, 1985; Wirth, 1938). More recently, however, social researchers have noted that community and social connections can be found in the most urban environments (e.g., R. E. Adams & Serpe, 2000; Fischer, 1982; Whyte, 1993) and that features of the built environment can be used by people to develop a “we feeling” with other residents in their neighborhoods (Hunter, 1974; Mannarini & Fedi, 2009; Mannarini, et al., 2018; Smith & Bugni, 2006; Suttles, 1968). In this article, we have drawn on theoretical ideas from symbolic interaction theory (Blumer, 1969; Smith & Bugni, 2006), behavioral geography (Steele, 1981; Wise, 2014), and architectural sociology (Zeisel, 1975) to analyze qualitative data from a study of a single neighborhood in Tehran, Iran, to show how residents use meanings attached to the built environment to develop a shared interpretation of themselves and others, which contributes to a sense of community, or a psychological and emotional connection to others in their community (B. Jones, 1984). This study has one major objective: evaluating the residents’ sense of community at Ekbatan Residential Complex by applying both architectural and sociological perspectives in assessing the buildings’ design and people’s quality of interaction. In particular, we employ symbolic interactionism to understand how residents of Ekbatan both symbolically construct the built environment, how they are, in turn, influenced by that environment, and how these factors work together. It also follows a line of research that examines factors affecting community life and a psychological sense of community in non‐US and non‐Western societies (Barati, Abu Samah, Ahmad, & Idris, 2013; Mannarini et al., 2018; Mannarini, Rochira, & Talo, 2012). 2 | LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 | Merging sociology and architecture As an academic discipline, sociology studies almost any type of social behavior that can occur within an urban environment and has also played an increasing part in understanding and interpreting architectural designs (B. Jones, 1984; Zeisel, 1975). One example of combining sociology and architecture (i.e., sociology of architecture) can be seen in the number of recent books and articles on this topic (e.g., Delitz, 2018; Francis, Giles‐Corti, Wood, & Knuiman, 2012; Gieryn, 2002; Smith & Bugni, 2006). A few of them use symbolic interactionism as a theoretical lens to better understand the built environment and how the design of buildings and the process of urbanization both influence how people see themselves, the interactions they may have with others, and reflects the meanings that people can attach to buildings, streets, highways, parks, neighborhood signs, and other objects in the community (Bugni & Smith, 2002). Architectural sociology focuses on the mutual relationship or overlap between physical environment, socio–cultural phenomena, and human behavior (A. Adams, Theodore, Goldenberg, McLaren, & McKeever, 2010; Bugni & Smith, 2002; Delitz, 2018; Jacobs, 1961; P. Jones, 2009; Smith & Bugni 2006). That is, how does the built environment affect the ways in which we live together and behave or interact with one another in social situations? By using sociological theory, architectural sociologists have the capacity to enhance the quality of design in buildings and communities, and, as a result, improve the quality of people’s lives. In the study of how children understand and use an eight‐story atrium in a children’s hospital in Toronto, Canada, for example, Adams and her associates (2010) combine sociological and architectural perspectives to gain a deeper understanding of how design affects the psychological health of sick children receiving treatment. Alternatively, Hunter (1974) in his study of the changing boundaries of Chicago neighborhoods finds that residents of higher status areas use features of the urban environment, such as street signs, major highways, and buildings to separate their neighborhood from less prestigious areas. MOLANA AND ADAMS | 3 Zeisel (1975) argues that the gap between the architect and his/her user clients has to be filled by establishing a common ground between them. Benefiting from sociological theories and methods to understand users’ needs is one of the primary foci among architectural sociologists. An environment constantly changes through time, and people’s behavioral pattern and social relations will experience a change in contact with their surrounding environment, a point also made by Park (1925). Taken from a social psychology perspective, symbolic interactionism deals with people and the ways they give meaning and value to the social and physical world (Cohen, 1985). “Meaning” is the foundation of the theory and it focuses on the question of which symbols and meanings emerge from the interaction between people? For architectural sociology, the given meaning is based on people’s interpretations and understandings of that environment (Gusfield, 2003; Smith & Bugni, 2006). Symbolic interactionists use the term “self” in describing a person’s needs, feelings, and how he/she sees his/herself, as well as how he/she appears to others (Gusfield, 2003). Smith and Bugni (2006) discussed architecture and built environment which includes buildings, bounded spaces, objects and many other elements that are part of architectural design, both reflects and influences self, human thoughts, emotions, and conduct. In this regard, symbolic interactionist theory comes into play to help our understanding of this correlation between architecture and people’s behavior and perceptions of their community. The work of Simmel (1950) argued that the self and surrounding physical environments are two distinct factors that can influence each other. In his paper, “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” he focused on the impacts that urban life has on an individual or self by noting that urban environments bombard residents with noise, crowded streets, many smells, and a complex social context. These various sorts of stimuli can overwhelm individuals leading them to erect psychological defenses that distance themselves from others. Mead (1934) significantly extends the subject of self and its correlation with physical environments and objects. He argued that objects, whether animate or inanimate, carry symbolic meanings in the environment and these meanings affect individuals’ self‐development and interactions within that environment. Following Mead (1934), Blumer (1969) argued that symbolic interactionism is fundamentally based on the meanings a person assigns to objects or the physical environment and that these meanings impact the self. Blumer (1969) identified three types of objects, “social,” “abstract,” and “physical,” which each of them affecting people’s conduct toward the tangible environment. Figure 1 depict the symbolic interactionism theory in one diagram by explaining the ways in which “self” and “object” interact and attach meaning to one another by merging Mead (1934) and Blumer’s (1969) arguments. FIGURE 1 Symbolic interactionism theory model 4 | MOLANA AND ADAMS 2.2 | The intersection of architecture, symbolic interactionism, and sense of community Based on the research of scholars such as McMillan and Chavis (1986), we argue that physical environments influence individuals’ interaction and shared feelings that developed through communicating in public or common spaces. A strong sense of community is the result of both a high‐quality interaction and satisfaction with living conditions. Based on McMillan and Chavis theory and definition, the sense of community has four dimensions that work together to develop a strong sense of community among community members. These four factors include: group membership (a feeling of belonging to a group and relatedness), influence (a sense that one’s ideas matter and can make a change in a positive way), integration and fulfillment of needs (an idea that one’s needs can be met by the community), and a shared emotional connection (a feeling of attachment or bonding with a community members; Brodsky, O’Campo, & Aronson, 1999; Fisher & Sonn 2002; McMillan & Chavis, 1986). Figure 2 merges the sense of community theory with symbolic interactionism, based on the Blumer’s (1969) symbolic interactionism model and McMillan and Chavis’s (1986) sense of community theory. An object has three forms—abstract, social, and physical—and the sense of community’s four dimensions only covers the two abstract and social forms of objects, expect the physical form of it. In the study of a housing project in Boston, for example, Small (2004) finds that older residents of the housing project were very satisfied because they “saw” it a better than the housing they lived in as young people. Younger residents were less satisfied because the “saw” the project as dilapidated and not as nice as the surrounding, more upscale, housing. That is, these two groups assigned different meanings to the housing project, resulting in different levels of housing satisfaction. Along with the idea that the same physical structure can carry meanings, symbolic interactionists propose that physical aspects of design—for instance: front or rear porches, street layout, park‐like spaces, wide sidewalks, local libraries, adequate outdoor lightings, easy access to service providers, nearby community gathering spots and child care centers—promote the quality of interaction and reinforce a sense of community among inhabitants (Francis et al., 2012; Higgitt & Memken, 2001). One aspect of design that directly intersect with reinforcement of sense of community among individuals is the quality of design (Francis et al., 2012). For example, the size of the public park and the presence of green space. Bugni and Smith (2002) in another research paper, concentrated on defining the notion of self and the way in which it can be influenced within the physical environment, as well as how an environment can convey meanings that affect self‐definition—how individuals evaluate themselves in comparing with other. Second, they argued against the formalistic aspect of contemporary architecture and design by proposing a humanistic paradigm that should be used in architectural theory and practice. They concluded by discussing how the shift from a formalistic to a humanistic paradigm could be accomplished. Their discussion continued by looking at the symbolic significance of FIGURE 2 Symbolic interactionism model in relation to sense of community MOLANA AND ADAMS | 5 the physical environment and the meanings it provides for self‐definition. In both of their papers, Bugni and Smith (2002), Smith and Bungi (2006) show the role of humanistic and symbolic interactionist paradigms in design. They believed these human‐centered perspectives could be widely used in contemporary architectural thought and practice. The authors also restated the significant role of architects in supporting people, organizations, and society by their design. They argue that balance between formalism and humanism will improve design, people’s quality of life, behavior and interaction. The research of organizational theorist, Hatch (1997), extended Blumer’s symbolic interactionist theory for use in architectural sociology by focusing on the physical structure of organizational life. She defined two sets of approaches in studying the physical environment within organizations: behavioral and symbolic. The behavioral approach sees the physical environment as key in shaping individuals’ behavior, and the symbolic approach sees people’s interactions and responses as a result of communicating in the physical environment that conveys meaning. Besides Hatch (1997), the research of Urry (1992) supported a similar argument that buildings have a potential in helping occupants in constructing meanings and feelings and consequently impact their psychological well‐being (see also, Brodsky et al., 1999). The research of Steele (1973) assessed the role of physical environments on human’s psychological well‐being. According to Steele (1973), factors such as security and shelter, social interaction, symbolic identification, task performance, pleasure and growth are some of the psychological consequences of space on individuals besides their conduct in a society. The study of Barati et al. (2013) in neighborhood councils in Tehran, demonstrated that the higher self‐efficacy is one of the major factors that motives individuals to participate in community activities and organizations which consequently lead to a strong sense of community with other community members (Barati et al., 2013; Glynn 1986). 3 | METHODOLOGY 3.1 | Case study: city of Tehran, Iran The city of Tehran has approximately eight million inhabitants (Asgharpour, Zanjani, & Talenghani, 2013) and is inhabited by the amalgamation of various ethnic groups in the country. Since its establishment as the capital of Iran over 200 years ago, it has grown to be one of the largest cities in the world. Established resources in the city, such as in education and health care, attracted many people from rural areas to search for better secure life. However, Tehran is deeply polarized and still with the considerable concentration of people and resources, the city suffers from many social and environmental problems that threaten people’s quality of life (Madanipour, 1999). Economic instability and price inflation are two of the major factors that divide the society into rich and poor social class. The residential environments are the evidence of this social gap in families’ lives. The north of the city is where the rich and upper‐class families live, on the other hand, the south side is mostly occupied by the poorer and the marginalized groups. The central part of Tehran is the business district where the majority of the local Bazars and government sectors are located (Asgharpour, et al., 2013). 3.2 | Ekbatan Residential Complex Ekbatan Residential Complex, comprised of 15,500 units, is in the central part of Tehran. The geographic location of the complex is physically and socially accessible to people who are from different social class. Ekbatan is a planned town built as a project of modern apartment buildings in the Western part of the city in the mid‐1970s (Figure 3). The goal of the project was to create the most modern, high quality housing project based on Western modular urban planning characteristics, and the latest technologies of that time to control the city’s population pattern and make affordable housing for governmental employees and staff (Sedighi, 2015). 6 | FIGURE 3 MOLANA AND ADAMS Ekbatan Residential Complex (Photo by Saeid Ghazi) The complex has 33 concrete blocks completed in three phases. The focus of this study is on the “phase one” consists of 10 blocks. The complex began the construction in 1970 and were completed in late 1979 during the time of Iran’s Islamic Revolution. After the Revolution, under the influence of the Islamic Republic, some luxurious elements of the complex that did not meet the Islamic regulations, such as outdoor swimming pools were demolished and replaced by gardens (Sedighi, 2015). Ekbatan is considered a successful mass housing project by its designers, and as a pleasant and peaceful living space by the most of its residents, due to the vigorous identity provided by outdoor spaces. The complex’s modern designed form ignores some traditions of Iranian housing, such as the use of concrete instead of bricks, open windows, and natural air circulation, with a series of concrete flats. However, the high‐quality public spaces and green areas are similar to the traditional courtyard houses and evoke the role of gardens in Persian architecture. Living in Ekbatan Residential Complex is like living in a small town. Sometimes residents do not leave the complex for a week or more, because they can satisfy their needs within the complex, such as schools, banks, shopping malls, parks, and restaurants, and even a hospital, library, and mosque. The complex is identified with a unique lifestyle and forms its own popular culture. It is the birth place of street arts of Parkour and urban graffiti in Iran (Sedighi, 2015). Figure 4 shows the group of young boys watching their friend playing parkour while listening to the music and sitting on the top of a wall with the graffiti art works painted on it. MOLANA AND FIGURE 4 ADAMS | 7 Ekbatan boys (Photo by Mohammad Shahhoseini) Ekbatan Residential Complex’s modular concept of its design gives people the opportunity to interact and behave in certain ways. For instance, residents show their comfort by dressing up more casually or feeling safe in an area due to the community’s boundaries. By evaluating the strong sense of community among the population of Ekbatan, this study applies symbolic interactionism to understand how and to what extent human relations can both attach meaning to buildings, entrance‐ways, and features of buildings and, in turn, be influenced by these meanings regarding the physical environment. 4 | DATA COLLECTIO N The data collected based on qualitative methods, such as participant observation and semistructured interviews with residents of Ekbatan. Conducting individual interviews or even simply spending time with them, allowed us to uncover and understand the ways and which architectural design or the physical environment of their surroundings influence people’s quality of interaction and sense of community. The interviews were collected from the total of 26 men and women between the age of 18–50. Each interview, depending on the depth of the shared information, took from half an hour to an hour. All the interviews were audio recorded in Farsi (Persian), however all the participants had an opportunity to refuse recording while answering the questions. Each part of data collection focused on different aspects of research objectives to assess the sense of community among residents. The participant observation, which was included taking photos and videos, mainly focused on the public places where residents interact mostly, as well as the quality of their interaction within different places—in other words, the duration and continuity in their contacts. Observation data also included evaluating the architectural elements of the complex, such as buildings’ layout, pedestrian paths, green areas, public 8 | MOLANA AND ADAMS spaces, and public amenities—for example, mosque, library, recreational center, malls, and shops. All the collected data recorded by photos, video and sketches of the space. The individual interviews conducted based on the observation data with various questions mainly framed around their satisfaction with both social and physical/architectural features of the community by asking questions, such as: how much having a shared park in the complex contributed to your life satisfaction in this community? Do you feel like you belong to a coherent social group? How much do you value your living environment and your social surrounding? Do you trust this community to raise your children? The main goal of interview questions was to understand the essence of sense of community’s formation and the factors contributed in this process. The two steps of transcription and interpretation were the main post‐interview process in analyzing the gathered data. The two main themes of architectural and social factors in reinforcing the sense of community and the ways and which residents attach meaning to their surrounds were used to categorize and classify interviews in two broad themes. For example, the subthemes below architectural factors included: public spaces, community facilities, site design, and green areas. The subthemes for the social factors are: socioeconomic status, age, gender, community helping, and marital status (Figure 5). 5 | RES U LTS One of the immediate results that analysis showed from individual interviews indicated the benefits of living within the community. The benefits include meeting individuals’ essential needs within the complex, having safety and security which is due to families’ long length of residency and high quality of public and green spaces. Besides shopping malls, the parks and public spaces connect residents to one another and increase sense of attachment to their living environment. The greenery in common places invites people to spend more time with each other outside of their private sphere. The buildings’ “W” form layout created the comfortable space for residents to have regular interactions. This interaction can be simply a short talk before leaving for work in the morning, watching children playing and exercising around the blocks. Over time, the communications and interactions change its value to a FIGURE 5 community Sociodemographic and architectural factors that contribute in creating SOC. SOC: sense of MOLANA AND ADAMS | 9 deeper sense of attachment not only to people, but also to the living environment. The trust bond among residents is the result of this shared satisfaction. Residents of Ekbatan, especially older adults, emphasized the significance of living in the complex on improving not only their mental health but their physical well‐being. For them having a social support in the case emergency, safe walkability within the neighborhood, quiet and green environment and accessibility to public transportation and finally feeling of belonging to a social group has a major positive impact on their lives. Analysis indicated that sharing a similar socioeconomic level, marital status, age and gender play an important role in keeping the community cohesive. Participant observation and interviews revealed the critical role of younger generations, particularly women, in creating or reinforcing the sense of community at Ekbatan Residential Complex. The majority of women are unemployed or housewives. Taking care of their children allows them to spend more time than men in public spaces, parks, or pedestrian paths. Every day at a specific time (early evening) they get together and meet for about 2 hours in the courtyard. Sometimes, they bring food and drink to share while they are talking about their personal concerns. One unexpected factor was the inter marriage among the residents who spent most of life in Ekbatan. Teenagers and younger adults, both girls and boys, have their own type of a small community or a group within the larger community. The complex provides education and learning groups for teenagers and adolescents. In this case, they have a choice either they want to leave the complex or stay within a neighborhood. Some of the adolescents have lived within the community since they were born. Having this long period of time growing up together, significantly helped them to create a bond with one another and develop a feeling of ownership to the community. This sense of ownership and shared attached meaning give the community an invisible boundary that delineates who is part of the community and who is not (insiders an outsider). This boundary makes residents feel safer and more secure within the complex and directly affect their level of involvement at the community’s events that require residents to spend more time in public and common spaces. The apartments at Ekbatan Residential Complex is divided into the two and three bedrooms apartments. Majority of the residents have a similar socioeconomic level who are mostly the owner of their place and came from the middle‐class families. Data analysis showed that the residents’ occupation or social status is a key component in reinforcing the sense of community and creating a homogenous community that no one is being discriminated because of the lower income comparing to other residents. Numbers of people are local business owners within the neighborhood. Having variety of local businesses and public sectors within the Ekbatan—such as library, mosque, schools, and recreational center—created the opportunity for residents to have either a full‐time or part‐time job and still stay actively involved within the community. Overall data analysis indicated the importance of balance between both social and architectural factors that created the strong sense of community at Ekbatan Residential Complex. The quality of the physical environment is a major reason why people feel safe and satisfied within the neighborhood. It affects individuals’ interaction by giving them an opportunity to attach symbolic meanings to their surrounding environments. The boundary among Ekbatan residents (or Ekbatani) are strong even when they are not in the complex. The adage, “Everywhere you will see an Ekbatani. However, if not, don’t worry. Because you’re Ekbatani!” was shared with us by a young resident of the complex. The phrase is one of the examples that indicates a strong sense of connection and attachment among the younger generations. This study is another evidence that demonstrates the importance of physical environments on building the sense of community and positively affect people’s general well‐being in a residential setting. Architects and urban planners by collaborating with environmental psychologists and architectural sociologists can make the opportunity for individuals to enhance their quality of interaction, sense of community and level of life satisfaction. 10 | FIGURE 6 MOLANA AND ADAMS Sense of community elements in correlation with three types of object 6 | CONC LU SION Sense of community is a useful tool in measuring people’s quality of interaction and life satisfaction; however, it has its limits. The main goal of this paper is to depict the ways and which we can understand and expand the sense of community’s formation and development by using symbolic interactionism theory. Utilizing the symbolic interactionism theory as a theoretical framework is a useful tool for understanding the attached meaning to the built environment surrounding its users. It assists designers to design the physical environments with considering the social and behavioral consequences of the built environment on individuals. Social scientists, especially symbolic interactionists believe that encouraging people to interact more within a community, collaborate, share symbols, and build network can lead to beneficial results. Altogether, these social actions will enhance the sense of solidarity, bolster a sense of community, strengthen a sense of attachment to a community and improve safety among people. One of the gaps that this study has identified was the lack of consideration to the physical type of an object based on Blumer’s work (1969) in the McMillan and Chavis’s (1986) sense of community theory. As it mentioned before, Blumer (1969) classified that an object has three manifestations in relation to a self: social, abstract and physical (Figure 1). In this case study in Ekbatan Residential Complex, the social objects are people or residents, abstract objects are feelings or emotions of the residents and physical objects are built environments or public spaces. According to Blumer, “the nature of all objects has meaning for the person or person for whom it is an object.” In this regard, Figure 6 shows the expansion of sense of community by applying symbolic interactionism theory and adding physical aspect of object besides social and abstract to a community formation. Finally, this study suggests that an alternative factor, “place attachment,” should be added to McMillan’s and Chavis’ (1986) factors of measuring people’s sense of community. Place attachment, by considering all types of objects—physical, social, and abstract—and based on symbolic interactionism theory, bridges social sciences and architectural design. The role that physical environments can play in influencing individuals’ perception and shared meaning are considerable in reinforcing a sense of community. The tools to measure sense of community (the four components) are limited in social aspects of human interaction and communication; however, symbolic interactionism theory—by looking at the three types of objects (social, abstract, and physical)—studies the individuals’ meaning attachment and the formation of boundaries. Ekbatan Residential Complex is an illuminating example of how a sense of community and community boundaries could be used to improve other residential projects by assessing the symbolic shared meaning among residents and examining such places through the lens of social science theories. MOLANA AND | ADAMS 11 OR CID Hanieh H. Molana http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9510-0781 REFERENC ES Adams, A., Theodore, D., Goldenberg, E., McLaren, C., & McKeever, P. (2010). Kids in the atrium: Comparing architectural intentions and children’s experiences in a pediatric hospital lobby. Social Science and Medicine, 70, 658–667. Adams, R. E. (1992). A tale of two cities: Community sentiments and community evaluation in Indianapolis and Pittsburgh. Sociological Focus, 25, 217–240. Adams, R. E., & Serpe, R. T. (2000). Social integration, fear of crime, and psychological health. Sociological Perspectives, 43, 605–629. Asgharpour, S. E., Zanjani, H., & Talenghani, G. (2013). Impact of urbanization on population changes in metropolitan area of Tehran, Iran. 3rd International Geography Symposium—GEO MED, Tehran, Iran. Barati, Z., Abu Samah, B., Ahmad, N., & Idris, B. K. (2013). Self‐efficacy and citizen participation in neighborhood council in Iran. Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 91–911. Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice‐Hall. Brodsky, A. E., O’Campo, P., & Aronson, R. (1999). PSOC in community context: Multi‐Level correlates of a measure of psychological sense of community in low‐income, urban neighborhoods. Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 659–679. Bugni, V., & Smith, R. (2002). Designed physical environments as related to selves, symbols, and social reality: A proposal for a humanistic paradigm shift for architecture. Humanity & Society, 26(4), 293–311. Cohen, A. P. (1985). The Symbolic construction of community. London, England: Ellis Horwood and Tavistock Publications. Delitz, H. (2018). Architectural modes of collective existence: Architectural sociology as a comparative social theory. Cultural Sociology, 12, 37–57. Durkheim, E. (1966). In J. A. Spaulding, & G. Simpson, Suicide: A Study in Sociology. New York, NY: Free Press. [1897] Fischer, C. S. (1982). To Dwell among Friends: Personal Networks in Town and City. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Fisher, A., & Sonn, C. S. (2002). Psychological sense of community in Australia and the challenges of change. Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 597–609. Francis, J., Giles‐Corti, B., Wood, L., & Knuiman, M. (2012). Creating sense of community: The role of public space. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32, 401–409. Gieryn, T. F. (2002). What buildings do. Theory and Society, 31, 35–74. Glynn, T. (1986). Neighborhood and sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 341–352. Gusfield, J. (2003). A journey with symbolic Interaction. Symbolic Interaction, 26, 119–139. Hatch, M. (1997). Organization theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Higgitt, N., & Memken, J. (2001). Understanding neighborhoods. Housing and Society, 28(1‐2), 29–46. Hunter, A. (1974). Symbolic Communities. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage Books. Jones, B. (1984). Doing sociology with the design professions. Clinical Sociology Review, 2, 109–119. Jones, P. (2009). A cultural political economy of architecture. Urban Studies, 42, 2519–2536. Madanipour, A. (1999). City profile: Tehran. Cities, 16, 57–65. Mannarini, T., & Fedi, A. (2009). Multiple senses of community: The experience and meaning of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 37, 211–227. Mannarini, T., Rochira, A., & Talo, C. (2012). How identification processes and inter‐community relationships affect sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 40, 951–967. Mannarini, T., Talo, C., Ntzani, N., Kritikou, M., Majem, L. S., Salvatore, S., … Brandi, M. L. (2018). Sense of community and the perception of the socio‐physical environment: A comparison between urban centers of different sizes across Europe. Social Indicators Research, 137, 965–977. McMillan, D., & Chavis, D. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 6–23. Mead, G. (1934). Mind, self and society from the standpoint of a social behaviorist. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Milgram, S. (1970). The experience of living in cities. Science, 167, 1461–1468. Nisbet, R. (1953). The quest for community: A study in the ethics of order and freedom. New York: Galaxy Book/Oxford University Press. Park, R. E. (1925). The city—Suggestions for the study of human nature in the urban environment. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Sedighi, M. (2015). Ekbatan. Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH), 12‐13, 232–257. Simmel, G. (1950). The metropolis and mental life. In K. H. Wolff (Ed.), The Sociology of George Simmel (pp. 409–424). New York: The Free Press. 12 | MOLANA AND ADAMS Small, M. L. (2004). Villa Victoria: The transformation of social capital in a Boston Barrio. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Smith, R., & Bugni, V. (2006). Symbolic interaction theory and architecture. Symbolic Interaction, 29, 123–155. Steele, F. (1973). Expanding professional design education through workshops in the applied behavioral studies. The Journal of Higher Education, 44, 380–388. Steele, F. (1981). The sense of place. Boston, Mass: CBI Pub. Co. Suttles, G. D. (1968). The social order of the slum. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. Tonnies, F. (1957). In C. P. Loomis (Ed.), Community and society. New York: Harper Torchbook. Urry, J. (1992). The tourist gaze and the environment. Theory, Culture, and Society, 9, 1–26. Whyte, G. (1993). Escalating commitment in individual and group decision making: A prospect theory approach. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 54, 430–455. Wirth, L. (1938). Urbanism as a way of life. American Journal of Sociology, 44, 3–24. Wise, N. (2014). Placing sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 7, 920–929. Zeisel, J. (1975). Sociology and architectural design. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY I am originally from Kish Island, Iran. I received my Bachelor’s degree in Architecture from Tehran University in Spring 2014 and attended the Master of Science in Architecture and Environmental Design program at Kent State University starting in Fall 2014. My Master’s thesis used qualitative research methods to evaluate the sense of community in the residential neighborhoods in the city of Tehran. It focused specifically on the ways in which both environmental and social factors influence individuals’ quality of interactions, sense of community and place attachment. After graduating in Spring 2016 with a M.S. my interest in social sciences and urban studies led me to continue to expand upon my research in the geography program at Kent State University as a Ph.D. student. Currently, I am working on my dissertation studies and recently defended my candidacy examination. My dissertation forms around female immigrants’ acculturation process and identity adjustment in the U.S., as well as its impact on individuals’ mental health and self‐perception. The Iranian immigrants’ community in Los Angeles is being used as a case study to answer the research questions. Alongside my research process, I have been teaching the geography courses as an instructor including Geography of the Middle East, Introduction to Geography and World Geography. I am expecting to defend my dissertation in Fall 2020 and continuing to follow my passion which is teaching and conducting research. How to cite this article: H. Molana H, Adams RE. Evaluating sense of community in the residential environment from the perspectives of symbolic interactionism and architectural design. J. Community Psychol. 2019;1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22214 View publication stats